A telehealth mental health programme was designed at the LivingLab of the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad de Antioquia [University of Antioquia].

ObjectivesTo describe the development and operation of the programme and evaluate the satisfaction of the patients treated during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

MethodsDescriptive study that details the development of the programme. Data were extracted from medical records to describe the patients who were treated. A satisfaction scale was applied to a random sample and the data were summarised with descriptive statistics.

ResultsIn March 2020 and August 2021, 10,229 patients were treated, with 20,276 treated by telepsychology and 4,164 by psychiatry, 1,808 by telepsychiatry and 2,356 by tele-expertise, with a total of 6,312 visits. The most frequent diagnoses were depressive (36.8%), anxiety (12.0%), and psychotic (10.7%) disorders. Respondents were satisfied to the point that more than 93% would recommend it to another person.

ConclusionsThe LivingLab telehealth mental health programme allowed for the care of patients with mental health problems and disorders in Antioquia during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, and there was a high degree of satisfaction among the beneficiaries. Therefore it could be adopted in mental health care.

En el LivingLab de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Antioquia se diseñó un programa de telesalud mental.

ObjetivoDescribir el desarrollo y el funcionamiento del programa y evaluar la satisfacción de los pacientes atendidos en 2020 y 2021 durante la pandemia de COVID-19.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo que detalla el desarrollo del programa. Se extrajeron los datos de las historias clínicas para describir a los pacientes atendidos. Se aplicó una escala de satisfacción a una muestra aleatoria y se resumieron los datos con estadística descriptiva.

ResultadosDurante marzo de 2020 y agosto de 2021, se atendió a 10.229 pacientes con 20.276 atenciones por telepsicología y 4.164 por psiquiatría, 1.808 en la modalidad de telepsiquiatría y 2.356 en la de teleexperticia, con un total de 6.312 atenciones. Los diagnósticos más frecuentes fueron trastornos depresivos (36,8%), ansiosos (12,0%) y psicóticos (10,8%). Los encuestados se mostraron satisfechos, al punto de que más del 93% recomendaría el programa a otra persona.

ConclusionesEl programa de telesalud mental del LivingLab permitió la atención de pacientes de Antioquia con problemas y trastornos mentales durante los primeros 2 años de la pandemia de COVID-19 y los beneficiarios mostraron un alto grado de satisfacción, por lo que podría adoptarse para la atención en salud mental.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented recent event that has significantly impacted the mental health of the world's population. Many different psychological reactions can occur, and it is estimated that they are quite common. According to data from a systematic review of the literature, the most prevalent are sleep disorders (40%), stress (34%), post-traumatic stress symptoms (27%) and anxiety (26%) and depressive (26%) syndromes, and they lead to a high burden of psychological morbidity.1 These alterations can affect people's lives, cause mental disorders, or precipitate exacerbations in patients with previous disorders.2,3 This is especially important in subgroups, such as those who become infected and healthcare workers, who appear to be more vulnerable.4,5

There are multiple factors involved in the impact on mental health. On the one hand, the infectious disease itself is a stressor due to the physical disability it can cause and the concern about the risk of death and contagion of family and friends.6 On the other, measures to address it include confinement and social distancing, which also have harmful effects. For example, they have an impact on socialisation and daily life, with it being impossible to do study, work and leisure activities normally,7 with changes in domestic life that can even generate violence.8 These measures also have a significant and lasting economic impact, with high unemployment rates and bankruptcies in multiple sectors of the economy.9

Fighting this “parallel epidemic”10 of mental health conditions is challenging, because the high demand exceeds the structure of mental health services. In a survey carried out by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 130 of its member states, a lack of financing for mental health services was found, despite the increase in demand with the pandemic.11 Furthermore, 93% of countries reported interruption of mental health services, mainly outpatient consultations, which makes it even more difficult to respond to the population's needs. In fact, an increase in emergency psychiatric consultations was reported in some cities in 2020, especially for adults with a history of mental disorders, which could be explained by treatment interruptions and greater vulnerability due to their diagnosis.12,13

In light of this backdrop, the need to adapt mental health care is evident, so that we can guarantee effective access to diagnosis and treatment for people with new symptoms after the pandemic, provide continuity for patients already in follow-up for any psychiatric diagnosis and develop prevention and promotion strategies for mental health.14 We have to organise these adaptations into levels, taking into account the wide spectrum of mental health needs which may be met with different interventions, such as psycho-education, short psychological intervention or prescribing of psychotropic drugs by psychiatry. One strategy that can be carried out by this organisation, especially in low-income countries, is to implement programmes capable of evaluating needs, monitoring symptoms, addressing crises, providing brief interventions and directing people to specialised services.15–17

There have been recommendations to intermediate the provision of this type of mental health services with information and communication technologies (ICT) to reduce the risk of contagion and because of the immediacy of the problem, as this could improve the opportunity for care.18,19 Using virtual platforms, telephone call centres or video calls, in addition to helplines available all hours of the day for crisis care, it has been possible to provide support to people with mental symptoms in the context of the pandemic.20,21 Telehealth has also made it possible to provide care for rural and dispersed populations, so is being promoted as a useful and acceptable care model.22

In Colombia, the Faculty of Medicine of Universidad de Antioquia has the Hospital Digital-LivingLab Telesalud [Digital Hospital-Telehealth LivingLab] as a space where the State, the public sector, academia and citizens actively participate in the innovation process, co-creating solutions to health problems through ICT. One such solution was the targeted telehealth mental health programme, in which telephone lines were available for permanent telecounselling, telepsychology and telepsychiatry care for the entire population of the Department of Antioquia (Colombia). The experience with this programme has contributed to formulating and improving mental health interventions during the pandemic and post-pandemic. The aim of this study is to describe the development and operation of this programme and evaluate the degree of satisfaction of patients supported during 2020 and 2021.

MethodsDescriptive study on a telehealth mental health programme and the satisfaction of the patients treated. This study complied with the Colombian ethical and legal framework and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Universidad de Antioquia's Faculty of Medicine in Medellín (Colombia).

Development of the programmeThe LivingLab Telehealth-Digital Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine is a space to integrate ICT in the search for solutions to health problems in coordination with the Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud [Colombian Healthcare Social Security System]. Work was underway on a mental health care programme aimed at regions of Antioquia. With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which could lead to an increase in morbidity due to psychiatric disorders and difficulties in in-person psychiatric and psychological care, it was therefore decided to review the model so that quality care could be provided to people with mental problems.

After the pandemic was declared on 11 March 2019, a group of lecturers from the Department of Psychiatry in the Faculty of Medicine and the Department of Psychology in the Faculty of Social Sciences at Universidad de Antioquia reviewed the literature on psychological responses, psychiatric problems, and care recommendations in conditions of epidemic outbreaks, and also on telehealth mental health programmes. Based on this review, the programme was formulated with the coordination of the LivingLab-Hospital Digital telepsychology to ensure it could be properly implemented. Before starting the programme, we presented it to the rest of the Psychiatry teaching staff and modifications were made from their recommendations.

After patient care began within the programme, meetings continued to be held with the development team every two weeks to identify difficulties with the implementation and make the necessary corrections.

Description of care providedData was extracted from the records of the medical records system used in the programme. We established the number of patients treated by telepsychology and telepsychiatry and the number of sessions in which the patients participated. We compiled the clinical diagnoses coded in the medical record of the care given by each healthcare professional, using criteria from the Tenth Edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Diagnoses were classified as follows: depressive disorders (depressive episodes, recurrent depressive disorder and dysthymia); anxiety disorders (specific phobia, social phobia, panic disorder and generalised anxiety disorder); bipolar disorder (bipolar disorder and cyclothymia); schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, delusional disorder, acute and transient psychotic disorders, schizoaffective disorder and non-organic psychosis not otherwise specified); stress-related disorders (post-traumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder and adjustment disorders); and psychotropic substance use disorders (acute intoxication, harmful use, dependence, withdrawal and psychotic substance disorder). Obsessive-compulsive disorder, dementia and delirium were not grouped together. Other mental disorders were included in the category of other psychiatric disorders.

Satisfaction assessmentAfter searching the literature on satisfaction measurement instruments, none was found aimed at the adult population, specific for telehealth mental health and validated in Colombia. We therefore decided to design an instrument that could be applied quickly, to make a preliminary assessment of patient satisfaction in the programme. A group of two psychologists and three psychiatrists reviewed the literature on satisfaction scales in outpatient mental health services and telehealth. Based on this review, 24 items were generated that could be applied by telephone. A pilot test was carried out with 10 people who had participated in the programme. The think-aloud technique was used to answer the items, and they were asked to use their own words to describe the meaning of each one and give their opinion about the relevance of the questions. From this pilot test, items were modified and eliminated, and 15 remained. A second pilot test was done with another 10 people, and one more question was eliminated. The result was a 14-item questionnaire with four adjectival response options.

The questionnaire was administered by telephone to a sample of patients randomly chosen from those served by the programme. We calculated a sample size from the population served by telepsychology (10,229) and telepsychiatry (4,164) using the formula with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, and it worked out at 371 patients for telepsychiatry and 362 patients for telepsychiatry. From the list of the population sample, each subject was randomly chosen using the Excel formula " = aleatorio.entre" [random.between]. A "técnico en atención prehospitalaria" (TAPH) [member of the pre-hospital care team] rang the selected patients, explained the satisfaction assessment to them and, if the patient agreed, put the questions to them. Because it was impossible to validate and evaluate the psychometric properties of the instrument scores, we decided to describe the patients' responses to each of the items.

Statistical analysisSociodemographic information was extracted from each patient treated (age, gender, marital status, occupation, health insurance) and clinical diagnoses. The variables were presented with descriptive statistics. For categorical variables, absolute frequency and percentages were used. For the quantitative variables, the mean ± standard deviation were presented assuming, according to the central limit theorem, the normal distribution due to the size of the sample of patients included.

ResultsTelehealth mental health programmeThe telehealth mental health care programme was executed as summarised in Fig. 1. There is a telephone number for the population, attended 24 h a day by a trained TAPH (member of the pre-hospital care team), who identifies and characterises the patient. If severe acute symptoms are detected, psychological first aid (PFA) is provided. In this first contact, informed consent is explained and requested for medical care and processing of personal data, and a psychological triage is carried out, and the patient then referred to telepsychology or telepsychiatry. A systematised questionnaire created for the initial classification of the patient's risk is applied, which consists of 24 questions in six main areas: (a) risk to life for the patient or third parties based on the symptoms; (b) intensity of discomfort or suffering; (c) functional interference (areas of life); (d) risk to general health (diet, sleep); (e) history of needing psychotropic drugs or lack of adherence to psychiatric treatment; and (f) comorbidities or ongoing systemic illness.

Community telehealth mental health programme. Access to the programme is by ringing a 24 -h attention telephone number. It begins with the characterisation by a member of the pre-hospital care team and, according to the results of the psychological triage, telepsychology and telepsychiatry appointments are scheduled. In the case of patients classified as high risk, psychological first aid was given and emergency care routes activated, including referral to clinical centres, presence of the National Police and state departments for childhood, family or health, according to the need.

The results of the triage are produced automatically by the medical records programme, which shows the patient's risk and priority and thus allows interventions to be planned. Patients with emotional crises, aggression towards others, exacerbated mental disorder, psychosis, suicidal ideation with a structured plan or previous attempts, or without a support network, or acute intoxication, or who report being victims of violence (sexual, physical or psychological) are considered at high risk. They remain online with the TAPH until containment and activation of emergency routes are achieved (referral to clinical centres, National Police, Colombian Institute of Family Welfare, Prosecutor's Office, family services agency or local health or social inclusion departments). Immediate care is also provided by telepsychology (within no more than 3 h), with close follow-up after being attended by TAPH and psychology, and then the assessment by telepsychiatry is scheduled. Medium risk includes patients with persistent anxiety, depressive symptoms without suicidal risk or going through grieving processes. Psychological care is scheduled for within the next 12 h, and follow-up is scheduled 8–15 days after initial care, with assessment by telepsychiatry. Patients with problems in their support network or with mild symptoms without alteration in functionality are classified as low risk. They are scheduled for psychological care within the following 48 h and follow-up 8–15 days after initial care.

During the telepsychology evaluation, a comprehensive assessment of the patient's situation, a new screening of symptoms with semi-structured clinical interviews, psycho-education and counselling, crisis intervention, PFA if applicable, and follow-up programming for brief psychotherapeutic intervention are performed. In the case of telepsychiatry, appointments are made for specialised medicine for admission and check-ups according to the psychiatrist's clinical judgement. This area also provided the 'tele-expertise' modality, which consists of the real-time response to consultation with other specialist areas on patients with mental health needs admitted to the hospital admission units or Accident and Emergency departments of the municipal hospitals of Antioquia Region.

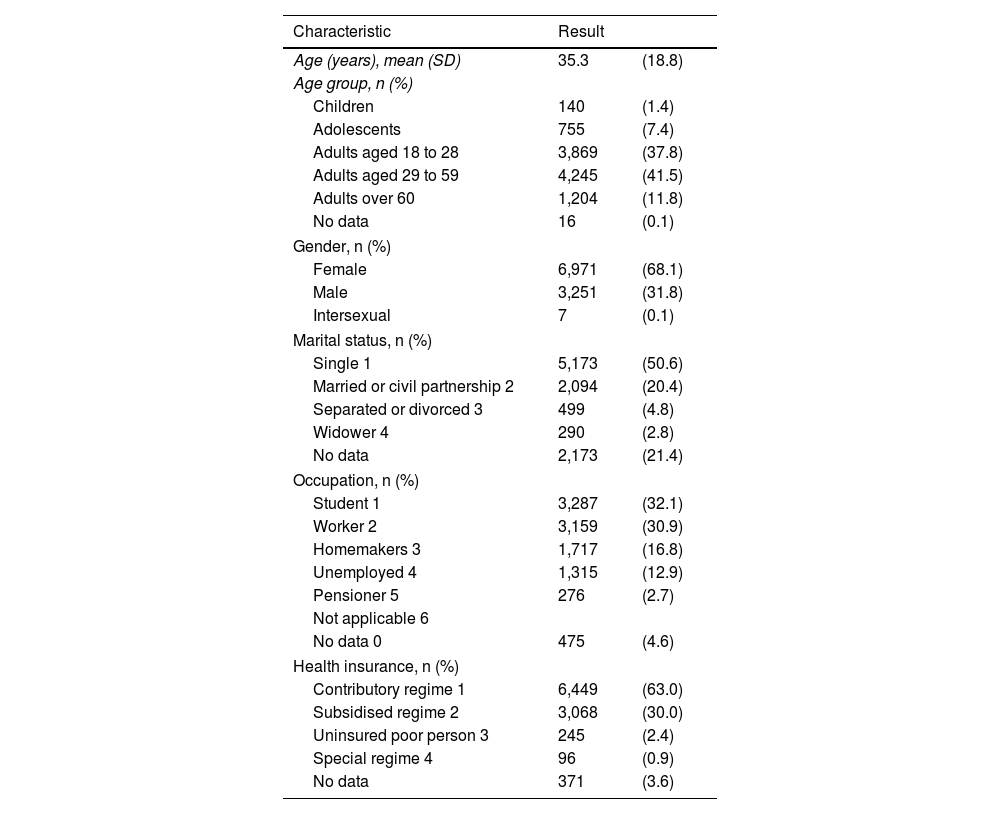

Care providedFrom 28 March 2020 to 31 August 2021, 297,428 calls were received, corresponding to all Telehealth agreements managed in the Livinglab in both the Mental Health and Physical Health areas. In telepsychology, 10,229 patients were treated according to risk: 2,164 (21.2%) at high risk; 3,665 (35.8%) at medium risk; and 4,400 (43.0%) at low risk. The demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the total number of patients treated by telepsychology, 9,435 (92.2%) received one to three sessions and 794 (7.8%), four to six sessions. The total number of telepsychology consultations dealt with was 20,276.

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients treated by telepsychology in a community telehealth mental health programme from March 2020 to August 2021 (n = 10,229).

| Characteristic | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 35.3 | (18.8) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| Children | 140 | (1.4) |

| Adolescents | 755 | (7.4) |

| Adults aged 18 to 28 | 3,869 | (37.8) |

| Adults aged 29 to 59 | 4,245 | (41.5) |

| Adults over 60 | 1,204 | (11.8) |

| No data | 16 | (0.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 6,971 | (68.1) |

| Male | 3,251 | (31.8) |

| Intersexual | 7 | (0.1) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Single 1 | 5,173 | (50.6) |

| Married or civil partnership 2 | 2,094 | (20.4) |

| Separated or divorced 3 | 499 | (4.8) |

| Widower 4 | 290 | (2.8) |

| No data | 2,173 | (21.4) |

| Occupation, n (%) | ||

| Student 1 | 3,287 | (32.1) |

| Worker 2 | 3,159 | (30.9) |

| Homemakers 3 | 1,717 | (16.8) |

| Unemployed 4 | 1,315 | (12.9) |

| Pensioner 5 | 276 | (2.7) |

| Not applicable 6 | ||

| No data 0 | 475 | (4.6) |

| Health insurance, n (%) | ||

| Contributory regime 1 | 6,449 | (63.0) |

| Subsidised regime 2 | 3,068 | (30.0) |

| Uninsured poor person 3 | 245 | (2.4) |

| Special regime 4 | 96 | (0.9) |

| No data | 371 | (3.6) |

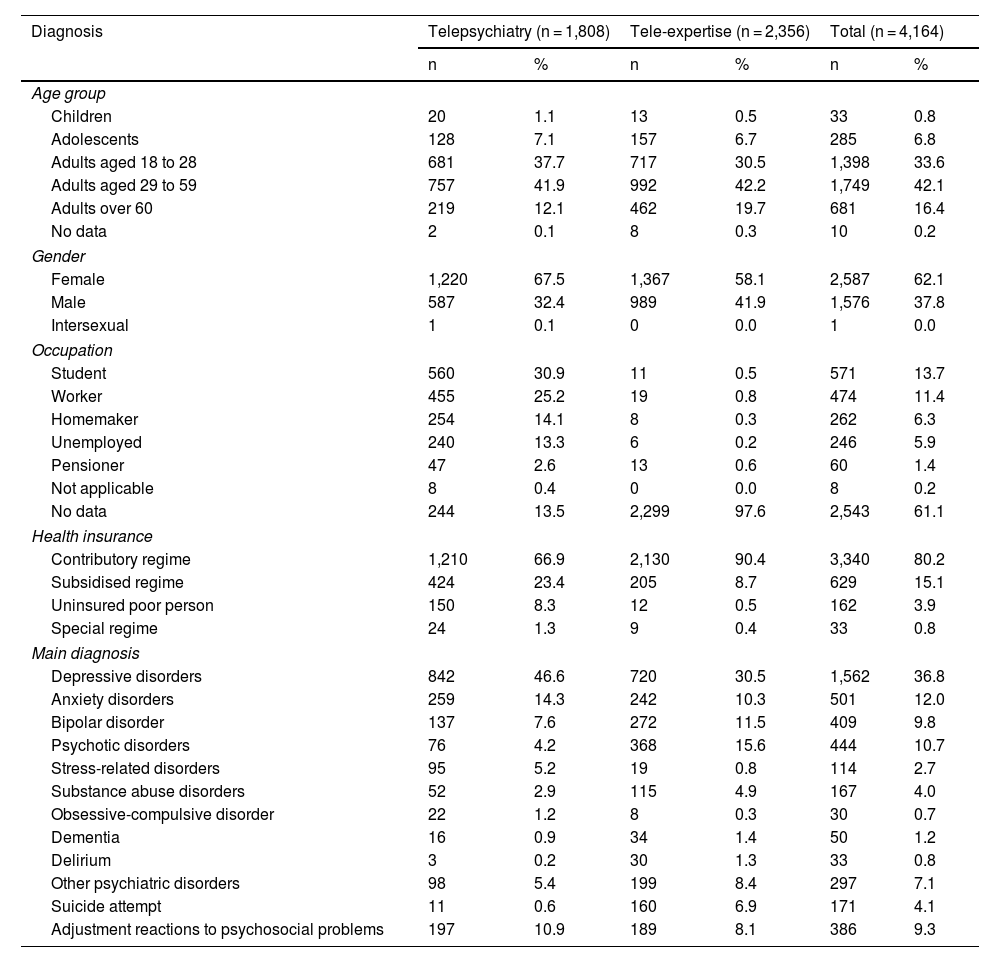

In the Psychiatry area, 4,164 patients were treated, and a total of 6,312 consultations dealt with. Under the telepsychiatry modality, 1,808 patients were treated. 94.8% received one to three sessions and 5.2%, four to eight sessions, totalling 2,824 consultations dealt with. In the tele-expertise modality, 2,356 patients were treated, 95.2% of whom received one to three sessions and the 4.8%, four or more sessions, for a total of 3,488 consultations dealt with.

The average age of the patients treated in the telepsychiatry modality was 35.4 ± 19.7 years. They were predominantly female, in the contributory social security regime and students. In the tele-expertise modality, the average age was 39.9 ± 17.3 years, with a higher rate of females and people affiliated with the contributory regime. In both groups of patients, the most common diagnosis was depressive disorders, followed in telepsychiatry by anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder and in tele-expertise by psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder (Table 2).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients treated by Psychiatry in a community telehealth mental health programme from March 2020 to August 2021.

| Diagnosis | Telepsychiatry (n = 1,808) | Tele-expertise (n = 2,356) | Total (n = 4,164) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age group | ||||||

| Children | 20 | 1.1 | 13 | 0.5 | 33 | 0.8 |

| Adolescents | 128 | 7.1 | 157 | 6.7 | 285 | 6.8 |

| Adults aged 18 to 28 | 681 | 37.7 | 717 | 30.5 | 1,398 | 33.6 |

| Adults aged 29 to 59 | 757 | 41.9 | 992 | 42.2 | 1,749 | 42.1 |

| Adults over 60 | 219 | 12.1 | 462 | 19.7 | 681 | 16.4 |

| No data | 2 | 0.1 | 8 | 0.3 | 10 | 0.2 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1,220 | 67.5 | 1,367 | 58.1 | 2,587 | 62.1 |

| Male | 587 | 32.4 | 989 | 41.9 | 1,576 | 37.8 |

| Intersexual | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Student | 560 | 30.9 | 11 | 0.5 | 571 | 13.7 |

| Worker | 455 | 25.2 | 19 | 0.8 | 474 | 11.4 |

| Homemaker | 254 | 14.1 | 8 | 0.3 | 262 | 6.3 |

| Unemployed | 240 | 13.3 | 6 | 0.2 | 246 | 5.9 |

| Pensioner | 47 | 2.6 | 13 | 0.6 | 60 | 1.4 |

| Not applicable | 8 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 0.2 |

| No data | 244 | 13.5 | 2,299 | 97.6 | 2,543 | 61.1 |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Contributory regime | 1,210 | 66.9 | 2,130 | 90.4 | 3,340 | 80.2 |

| Subsidised regime | 424 | 23.4 | 205 | 8.7 | 629 | 15.1 |

| Uninsured poor person | 150 | 8.3 | 12 | 0.5 | 162 | 3.9 |

| Special regime | 24 | 1.3 | 9 | 0.4 | 33 | 0.8 |

| Main diagnosis | ||||||

| Depressive disorders | 842 | 46.6 | 720 | 30.5 | 1,562 | 36.8 |

| Anxiety disorders | 259 | 14.3 | 242 | 10.3 | 501 | 12.0 |

| Bipolar disorder | 137 | 7.6 | 272 | 11.5 | 409 | 9.8 |

| Psychotic disorders | 76 | 4.2 | 368 | 15.6 | 444 | 10.7 |

| Stress-related disorders | 95 | 5.2 | 19 | 0.8 | 114 | 2.7 |

| Substance abuse disorders | 52 | 2.9 | 115 | 4.9 | 167 | 4.0 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 22 | 1.2 | 8 | 0.3 | 30 | 0.7 |

| Dementia | 16 | 0.9 | 34 | 1.4 | 50 | 1.2 |

| Delirium | 3 | 0.2 | 30 | 1.3 | 33 | 0.8 |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 98 | 5.4 | 199 | 8.4 | 297 | 7.1 |

| Suicide attempt | 11 | 0.6 | 160 | 6.9 | 171 | 4.1 |

| Adjustment reactions to psychosocial problems | 197 | 10.9 | 189 | 8.1 | 386 | 9.3 |

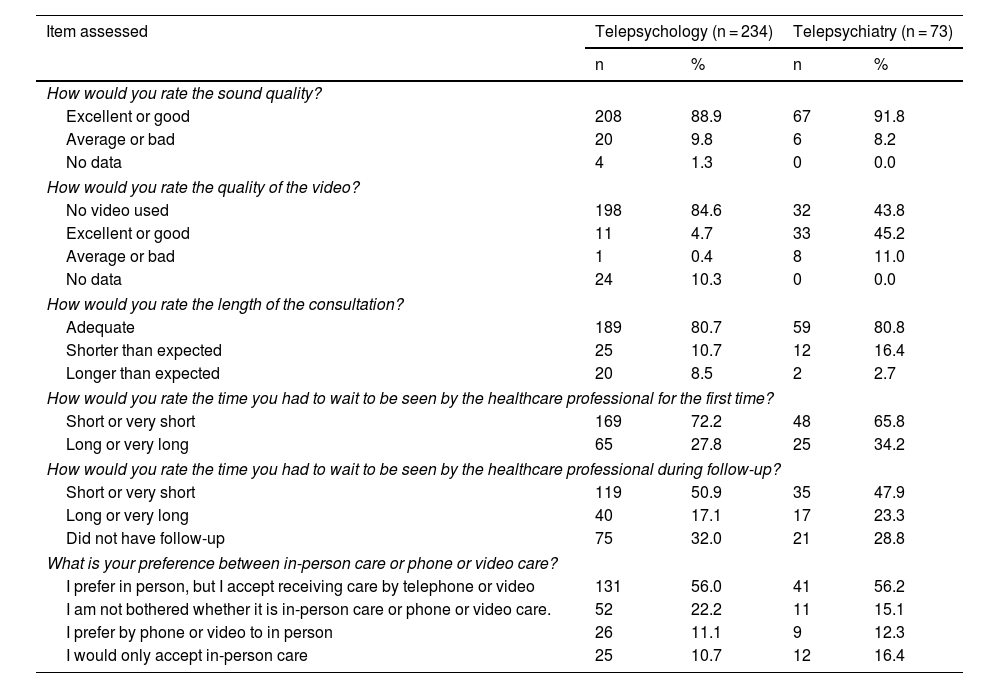

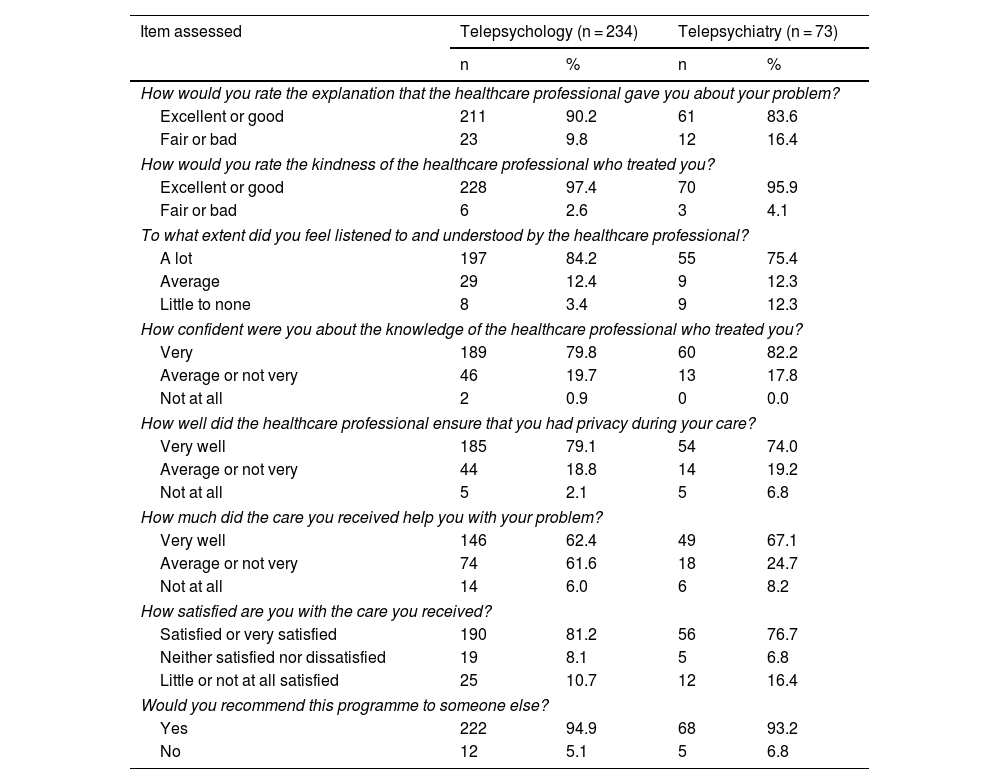

A total of 234 patients treated by telepsychology responded to the satisfaction survey (63.1% of the calculated sample). The remaining 36.9% (137) of the patients did not respond to the survey, either because the contact number was wrong or it was not possible to contact them after complying with the established call protocol (3 calls at 3 different times of the day and for 3 different days). The average age of the patients attended to by telepsychology was 37.8 ± 17.4 years, most (68%) were workers and students, and they mainly had diagnoses of depressive and anxiety (54.3%) and stress-related (25.2%) disorders. Of this sample, 199 (85.0%) reported that it was the first time they had ever received virtual care and 69 (29.5%) had difficulty accessing mental health services in person, mainly due to financial problems, distant place of residence and transportation difficulties. Most of these patients (84.6%) considered the care they received on admission from the TPAH (pre-hospital care team member) to be useful or very useful, and considered that the quality of the telepsychology service was adequate (Table 3). Regarding satisfaction with the staff in this area, most were satisfied and would recommend this programme to another person (Table 4).

Evaluation of the quality of the service provided to a random sample of patients treated by telepsychology and telepsychiatry in a community telehealth mental health programme.

| Item assessed | Telepsychology (n = 234) | Telepsychiatry (n = 73) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| How would you rate the sound quality? | ||||

| Excellent or good | 208 | 88.9 | 67 | 91.8 |

| Average or bad | 20 | 9.8 | 6 | 8.2 |

| No data | 4 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| How would you rate the quality of the video? | ||||

| No video used | 198 | 84.6 | 32 | 43.8 |

| Excellent or good | 11 | 4.7 | 33 | 45.2 |

| Average or bad | 1 | 0.4 | 8 | 11.0 |

| No data | 24 | 10.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| How would you rate the length of the consultation? | ||||

| Adequate | 189 | 80.7 | 59 | 80.8 |

| Shorter than expected | 25 | 10.7 | 12 | 16.4 |

| Longer than expected | 20 | 8.5 | 2 | 2.7 |

| How would you rate the time you had to wait to be seen by the healthcare professional for the first time? | ||||

| Short or very short | 169 | 72.2 | 48 | 65.8 |

| Long or very long | 65 | 27.8 | 25 | 34.2 |

| How would you rate the time you had to wait to be seen by the healthcare professional during follow-up? | ||||

| Short or very short | 119 | 50.9 | 35 | 47.9 |

| Long or very long | 40 | 17.1 | 17 | 23.3 |

| Did not have follow-up | 75 | 32.0 | 21 | 28.8 |

| What is your preference between in-person care or phone or video care? | ||||

| I prefer in person, but I accept receiving care by telephone or video | 131 | 56.0 | 41 | 56.2 |

| I am not bothered whether it is in-person care or phone or video care. | 52 | 22.2 | 11 | 15.1 |

| I prefer by phone or video to in person | 26 | 11.1 | 9 | 12.3 |

| I would only accept in-person care | 25 | 10.7 | 12 | 16.4 |

General satisfaction and satisfaction with the healthcare professional of a random sample of patients treated by telepsychology and telepsychiatry in a community telehealth mental health programme.

| Item assessed | Telepsychology (n = 234) | Telepsychiatry (n = 73) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| How would you rate the explanation that the healthcare professional gave you about your problem? | ||||

| Excellent or good | 211 | 90.2 | 61 | 83.6 |

| Fair or bad | 23 | 9.8 | 12 | 16.4 |

| How would you rate the kindness of the healthcare professional who treated you? | ||||

| Excellent or good | 228 | 97.4 | 70 | 95.9 |

| Fair or bad | 6 | 2.6 | 3 | 4.1 |

| To what extent did you feel listened to and understood by the healthcare professional? | ||||

| A lot | 197 | 84.2 | 55 | 75.4 |

| Average | 29 | 12.4 | 9 | 12.3 |

| Little to none | 8 | 3.4 | 9 | 12.3 |

| How confident were you about the knowledge of the healthcare professional who treated you? | ||||

| Very | 189 | 79.8 | 60 | 82.2 |

| Average or not very | 46 | 19.7 | 13 | 17.8 |

| Not at all | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| How well did the healthcare professional ensure that you had privacy during your care? | ||||

| Very well | 185 | 79.1 | 54 | 74.0 |

| Average or not very | 44 | 18.8 | 14 | 19.2 |

| Not at all | 5 | 2.1 | 5 | 6.8 |

| How much did the care you received help you with your problem? | ||||

| Very well | 146 | 62.4 | 49 | 67.1 |

| Average or not very | 74 | 61.6 | 18 | 24.7 |

| Not at all | 14 | 6.0 | 6 | 8.2 |

| How satisfied are you with the care you received? | ||||

| Satisfied or very satisfied | 190 | 81.2 | 56 | 76.7 |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 19 | 8.1 | 5 | 6.8 |

| Little or not at all satisfied | 25 | 10.7 | 12 | 16.4 |

| Would you recommend this programme to someone else? | ||||

| Yes | 222 | 94.9 | 68 | 93.2 |

| No | 12 | 5.1 | 5 | 6.8 |

From the telepsychiatry area, only 73 patients responded to the survey, which corresponds to 20.2% of the calculated sample; 79.8% did not respond to the survey due to the wrong contact number or because contact could not be made. The average age of the patients who responded was 36.7 ± 18.9 years and they were mainly students and workers (63%), and mainly diagnosed with depression or anxiety (59%). Of this sample, 45 (61.6%) reported that it was the first time they had ever received virtual care. The quality of the services was well rated (Table 3) and satisfaction with the staff was high, to the point that 93.2% would recommend care in the programme to another person (Table 4).

DiscussionThis study describes the development of a telehealth mental health programme and the results obtained after one and a half years of operation. Although some telehealth mental health interventions had already been launched at the Digital Hospital-LivingLab,23 it was with the COVID-19 pandemic that the challenge arose of structuring a far-reaching programme aimed at the general community for screening, diagnosis, treatment and monitoring patients with mental symptoms and thus covering the growing needs in mental health. Therefore, the current pandemic is seen as an unprecedented circumstance that catalysed the implementation of telemedicine.

This rapid increase could be modelled with Gartner's hype cycle,24 which describes a double peak effect in mental telehealth. The creation of the first television connections for psychiatric care in the 1960s initially acted as a trigger that led to reproducing experiences in clinical care through ICT, which became increasingly more common, and this could be considered the phase of inflated expectations (first peak). Then, in the first ten years of this century, a host of research began on its feasibility and effectiveness and the advantages it would have over in-person care, especially in remote regions. However, adoption in daily practice was slow, possibly due to barriers perceived by clinicians and regulatory aspects, so this could be seen as a phase of disillusionment. It was the pandemic that caused so many facilities to be provided for ICT care in an extremely short space of time, and this would be the slope of enlightenment phase (second peak).

The formulation and evaluation of telehealth mental health programmes has become a worldwide objective, and we see that the urgency to design programmes like ours was the same in different parts of the world, either due to the need to adopt virtual care provision in treatments that had been in person and avoid delays,25–29 or to cover the demands deriving from the stressful experience of the pandemic.30–33 This collection of experiences is evidence that ICT-mediated mental health care has not only increased, but is a feasible strategy. It therefore seems reasonable to think that after this new slope of enlightenment, with the demonstration of benefits in patients, there will be widespread adoption of telehealth as a way to organise mental health services; which would be the last phase of the Gartner cycle, the plateau of productivity.24

Our telehealth mental health programme was designed in response to a need to meet the demand created by mental symptoms suffered by people in the community. Through a 24 -h telephone line, people in the department of Antioquia received formal assessment and diagnosis, psychoeducation about their condition, psychotherapeutic treatment, and prescription of psychotropic drugs. There was a wide range of services offered, consistent with the mental health needs identified with the pandemic.34 The route to access the different services was determined by the initial assessment of the patients' needs by the trained member of the pre-hospital care team. This risk-based prioritisation allows the resources available to each programme to be distributed, and is therefore especially recommended for low-income countries.35

Having a free helpline is a resource reported as useful, as it can provide an immediate response so that people affected by the pandemic can receive support and intervention. In China, although they existed before the pandemic, community service telephone lines increased considerably with the pandemic to provide interventions in the midst of mental symptoms and also as a resource for guidance and information.36 As in our case, the main psychopathological symptoms treated by this resource in China were depression and anxiety, as well as sleep problems. After the call, most patients felt emotionally better, and that is why they agree that the hotlines had helped them.37,38

Although telemedicine became the pillar of clinical care in the pandemic, the evaluation of programmes based on it is still a challenge.39 This study reports a high degree of satisfaction in a subsample of patients who, due to their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, would be considered representative of the total sample. This outcome is an indicator traditionally used to measure the performance of health services, and denotes the degree of agreement between the care expected by the patient and that finally provided by the institution.40 In telehealth mental health programmes, even those implemented before the pandemic, the degree of patient satisfaction has been consistently high.24,41 Compared to face-to-face services, the degree of satisfaction is considered comparable, as is the therapeutic alliance that can be developed.42

Although it initially operated as a contingency plan to deal with the mental health impact of the pandemic, community provision of mental health care using ICT should continue and could become an alternative to be offered on a permanent basis. Given the level of development achieved and the high degree of patient satisfaction, it could be a good proposal to adopt this type of programme. However, for the future it is necessary to evaluate their effectiveness in terms of symptoms, costs, sustainability and social impact, and the perspective of the clinicians. We also need to examine the necessary integration with the health insurance system, in order to guarantee the continuity of the treatments initiated in the programme.

Among the limitations of this study is the collection of data from the records, which may be incomplete because it depends on the information being adequately recorded, and explains why there is a relatively high percentage of missing data in some variables. We also need to acknowledge that we only measured the satisfaction perceived by the patients treated, and not other clinical outcomes, such as the improvement in mental symptoms or the number of hospital admissions that have occurred since the implementation of the programme; this outcome seemed to decrease with telehealth mental health services.41,43 It might also be thought that the degree of satisfaction is overestimated, as those willing to answer surveys are usually satisfied. However, we attempted to reduce this bias by taking a random sample. We also need to point out that the measuring instrument used has yet to be validated in Colombia, so its validity and reliability in our environment are unknown. However, the development process was rigorous, and its validation could be considered in future research. Furthermore, it must be taken into account that the individual features of the Colombian healthcare system and the attention given to emergencies, including the pandemic itself and psychiatric emergencies, mean the programme must be seen as a particular experience from which one can learn. It cannot be directly transferred to other contexts without a review process to ensure its proper implementation.

ConclusionsWith the COVID-19 pandemic, a telehealth mental health programme was structured aimed at the general community of the Department of Antioquia for screening, diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of patients with mental symptoms, with telecounselling, telepsychology and telepsychiatry services. After one and a half years in operation, many patients have been treated, and a high level of satisfaction has been achieved. In view of the level of development achieved when creating the programme and the outcomes perceived by patients, this type of ICT-mediated programme could be adopted for continuing mental health care.

FundingThis research was funded by the Faculty of Medicine of Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín (Colombia) under Project 2630.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare for this work.

To the entire LivingLab team for their hard work, especially during the pandemic. To the Government of Antioquia for its support in implementing the programme. To the Government of Antioquia and the Regional Department of Health and Social Protection of Antioquia for the support within the framework of contracts 4600010592 and 4600011985 executed between 2020 and 2021. To the Ministry of Health of Medellín for the support in the operation of the programme within the framework of contracts 4600085477, 4600089192 and 4600090169 from 2020 to 2021. Also to the Anniversary Welfare areas of the Universidad de Antioquia and the EAFIT private university for their support within the framework of the agreements. Finally, to the different Entidades Administradoras de Planes de Beneficios de Salud (EAPB) [Health Benefit Plan Administrative Bodies] with which LivingLab has an agreement to provide services, as they were instrumental during the pandemic.