To look for structural and/or functional deviations of the salience network in depressive patients that might help to identify individuals with ideation of suicide.

Material and methodsIn 2 matched groups of patients with major depression and with and without ideation of suicide and in a healthy control group, structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging was performed during resting state and activation by a moral decision paradigm. Data were evaluated using voxel based morphometry, statistical parametric mapping, independent component analysis and network-based statistics (NBS) and related to the Clinical Analysis Questionnaire score of suicidality.

ResultsFunctional connectivity was reduced significantly (p<0.05, NBS corrected) within the salient network during resting state in patients with suicide ideation. Application of a moral paradigm activated nearly identical areas, and both anterior parts of the insulae correlated negatively to the score of suicidality.

ConclusionBecause the cerebral areas activated during a moral decision paradigm are nearly identical to the salience network seen in our study and because selected areas within this network, mainly the anterior parts of the insula, correlate negatively to suicidality, a special training using moral tasks or possibly also religious reinforcement might help to reduce suicidality in depressive patients.

Buscar desviaciones estructurales y/o funcionales de la red de saliencia en pacientes depresivos que puedan ayudar a identificar individuos con ideación suicida.

Material y métodosA dos grupos combinados de pacientes con depresión mayor y con y sin ideación suicida, y a un grupo control sano, se les realizó resonancia magnética estructural y funcional (fMRI) en estado de reposo y activación utilizando un paradigma de decisión moral. Los datos se evaluaron mediante morfometría basada en vóxeles, mapeo paramétrico estadístico, análisis de componentes independientes, estadísticas basadas en redes (NBS) y se relacionaron con la puntuación de un cuestionario de análisis clínico de tendencias suicidas.

ResultadosLa conectividad funcional se redujo significativamente (p<0,05, NBS corregido) dentro de la red saliente durante el estado de reposo en pacientes con ideación suicida. La aplicación de un paradigma moral activó áreas casi idénticas y ambas partes anteriores de la ínsula se correlacionaron negativamente con la puntuación de tendencias suicidas.

ConclusiónDebido a que las áreas cerebrales activadas durante el paradigma de decisión moral son casi idénticas a la red de saliencia vista en nuestro estudio, y debido a que áreas seleccionadas dentro de esta red, principalmente las partes anteriores de la ínsula, se correlacionan negativamente con la tendencia suicida, un entrenamiento especial usando tareas morales o posiblemente también de refuerzo religioso podría ayudar a reducir las tendencias suicidas en pacientes depresivos.

During the second and third decades of life, suicide is the second leading cause of death and is prognosticated to rise further. Suicidal ideation seems to be a key variable in suicide prevention.1 There are ethnic differences. Hispanics still have lower rates of suicide compared to other ethnic or racial groups,2 but the factors that mediate this effect are not known. In 2016, the Dominican Republic reported 569 deaths by suicide, presenting a mortality rate of 5.7 per 100,000 inhabitants.3 Examination of a sample among Latino youths found 8.7% of suicide attempts per year, rising with greater US cultural involvement.4

Some protective factors may be related to cultural constructs that provide a buffer against suicidal behavior in the face of psychiatric illness. Multivariate analyses suggested that although being Latino was independently associated with less suicidal ideation, other suicidal behaviors held a stronger relationship to moral objections to suicide and survival and coping skills than to ethnicity. Especially moral and religious objections to suicide have been identified as protective mechanisms.5

Several neuroimaging studies demonstrated structural and functional alterations in suicide attempters with bipolar disorders, mainly decreases in gray matter and white matter structural and functional connectivity in a ventral fronto-limbic neural system involved in emotion regulation and in fronto-parietal networks that could represent factors of vulnerability.6 Regions involved have been identified as default mode and salience networks. The latter network is strongly related to moral emotions and decision making.7,8

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study presented here compared two groups of Dominican patients of a depression ambulance, one with and one without suicidal ideation, and a control group. Examinations were concentrated on the salience network during resting state and on brain areas involved in moral decision making. We aimed to look into neuro-anatomic and functional alterations to understand and possibly prevent further increase of this important public health problem in a community, where religion and strong family ties still have an important social tradition.

Material and methodsThe study had been approved by the local ethic committee and informed consent had been received by all participants.

Patients and controlsThis prospective study included 39 patients with the diagnostic criteria of major depressive disorder as listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-59 from an outpatient psychological consultation service. According to the Clinical Analysis Questionnaire (CAQ),10 mainly to its depression and suicidal depression scales, they were grouped into two samples: a group of 20 patients, who at the time of evaluation had expressed suicidal ideas, consisted of 10 women and 10 men with a mean age of 29.8 (19.6–45.2) years, while the other 19 patients without suicidal ideas were 12 women and 7 men with a mean age of 31.1 (22.8–47.1) years. A third group of 16 participants with a mean age of 30.3 years (8 women and 8 men) served as healthy controls. The three groups had a similar social environment: they were singles, usually had a university education and belonged to middle-class families.

Psychological testsThe Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a short and simple test that is useful in the “screening” of cognitive performance, its estimation and the evaluation of the changes produced over time.11 The CAQ was specially constructed to meet the need for a single instrument that could simultaneously measure normal and pathological features, allowing the construction of a complete and multidimensional psychological profile based on twelve clinical variables.

Magnetic resonance imagingAll examinations were carried out on a 3 Tesla Philips Achieva scanner release 2.6 equipped with an 8-channel head coil and included the following structural and functional sequences

- •

T2W sequence: TR/TE=2050/80ms, 25 transversal slices, thickness 5mm

- •

T1W MPRAGE sequence: TR/TE=6.73/3.11ms, 180 sagittal slices, voxel size 1mm3

- •

EPI-gradient echo sequences: TR 2s, 34 slices of 3mm thickness providing full brain coverage, gap 0.75mm, FOV 192mm, voxel size 2.38mm×2.38mm×3mm with 180 dynamics over 6min for resting state and with 240 dynamics over 8min for the moral decision activation study. For the resting state condition, patients were requested to lie quiet in the scanner with eyes closed thinking of nothing special but to let their minds wander around. The paradigm for the activation study consisted out of 6 one-minute-blocks starting with the presentation of a moral dilemma similar to those published by Garrigan et al.19 (explaining text for 20s and illustrating figure combined with the question what the person would decide for 15s), followed by the request to take a yes or no decision by pressing one of two buttons for 5s and a final period of rest for 20s.

Results of were compared between groups by 2-tailed t-test. Significance was accepted on a 95%-level, corrected for false discovery rate (FDR, www.sdmproject.com/utilities/?show=FDR).

Calculation of grey matter densityGrey matter density was calculated from T1-weighted images using the Computational Anatomic Toolbox (CAT) 12.1 (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat12/) implemented in SPM 12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). This program is based on high resolution structural 3D MR images and allows for applying voxel-wise statistics to detect regional differences in grey matter density and calculation of cortical thickness. Pre-processing involved spatial normalization, grey matter segmentation, non-linear modulation and smoothing with a kernel of 8mm×8mm×8mm. Correlation of grey matter density to scaling of suicidality was analysed by multiple regression analysis section of the CAT toolbox on a voxel-wise basis, with total intracranial volume, age and results of mini-mental test as covariates to minimize the effect of these parameters. Significance was accepted on an individual cluster peak level of 95%, corrected for multiple comparison.

Functional MRI of activation during moral decision makingImage preprocessing and statistical analysis was performed with statistical parametric mapping (SPM12, www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) running under Matlab (MathWorks). The preprocessing involved slice timing, realignment, spatial normalization to a standard EPI template and smoothing with an 8mm Gaussian kernel. As active dynamics, those covering the period of presenting the illustration of the moral dilemma and the request to take a decision were taken to look for areas activated by application of the paradigm. Data were corrected for motion, age of patients and results of mini-mental tests and evaluated by one-sample t-test over all participants. Final results were achieved by SPM 2nd level analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the suicidality score as covariate. Significance was accepted on a 95%-level, corrected for multiple comparison.

Functional MRI of resting stateWithout smoothing of data, signal intensities of all voxels in one region were averaged for each time point, followed by regressing out head movement parameters (six parameters, calculated during the movement correction step), cerebrospinal fluid signals, and white matter signals (both extracted from a 5mm spherical ROI using Marsbar Toolbox (http://marsbar.sourceforge.net/). We also applied global signal regression to remove sources of global variance such as respiration and head movements. Framewise displacement was calculated as the sum of absolute values of the derivatives of the 6 realignment parameters. Frames presenting values below 0.5 were discarded from further data evaluation.

From resting state data, independent component analysis (ICA) was carried out using the Group ICV FMRI Toolbox (GIFT) running under Matlab. The program allows for extraction of signals of interest without any prior information about the task. Here, spatially independent brain sources or components were calculated as regions of interest (ROIs) from fMRI data. Extraction of independent components was limited to 20 and the “Infomax” algorithm was used. From the 20 components extracted, that one with highest similarity to the salience network as defined by Shirer et al.12 (Fig. 1) was taken from every participant.

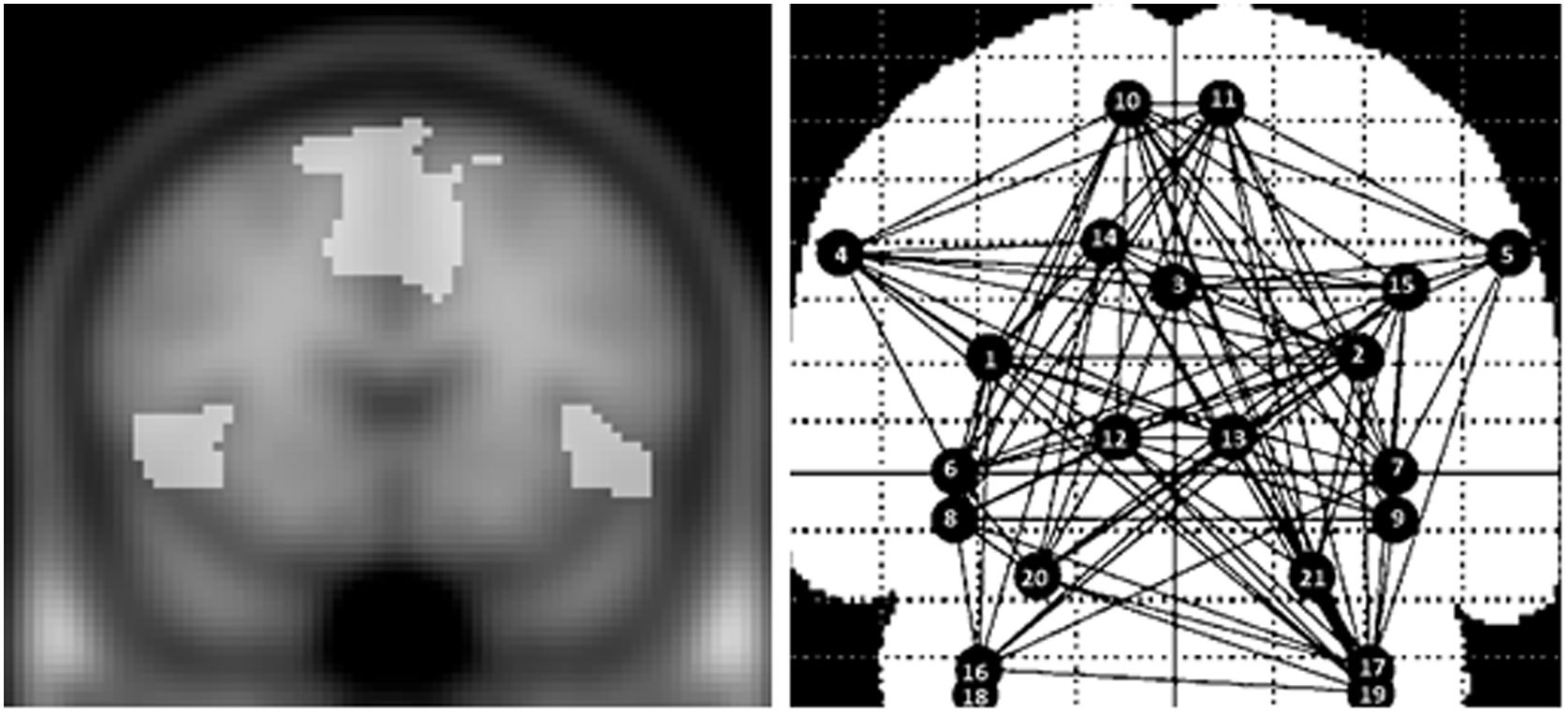

Salience network taken from Shirer et al. (2011) projected into a standardized brain image (left) and representation of these ROIs in a graph (ap projection) calculated by NBS evaluation (right). 1/2: midfrontal gyri, 3: medial prefrontal cortex, 4/5: inferior parietal lobules, 6/7: anterior insulae, 8/9: posterior insulae, 10/11: superior parietal lobules, 12/13: thalami, 14: posterior cigulate gyrus R, 15: dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex L, 16/17: superior cerebellum, 18/19: inferior cerebellum, 20/21: amygdalae.

Region-averaged time series of signals were extracted from all areas included in the salience network mentioned above. Signal time course extracted from both amygdalae were included in the salience network. Masks of the amygdalae were taken from the automatic anatomic labelling (AAL) atlas (https://www.gin.cnrs.fr/en/tools/aal/). Coefficients between signal time courses from all 21 ROIs included were tabulated and formed a matrix of functional connectivity for every participant. To calculate correlation of network connectivity to suicidality score and to correct for multiple comparison, we applied network based statistics (NBS, nitrc.org/projects/nbs). NBS controls for multiple comparisons through cluster-based thresholding, in which connected components of a network are considered a cluster. Correlation of connectivity to suicidality was calculated using the ANCOVA section of NBS, with 5000 permutations each, flipping the sign of each data point for each mutation, at a significance level set to p<0.05. Measurement of significance was based on the number of connections between ROIs (Fig. 1).

ResultsPsychological testsIn contrast to the mini-mental and all 5-digits and TESEN tests, some of the CAQ tests showed some significant differences between patients with and without ideation of suicide: according to the definition of both groups, the difference was largest in the CAQ suicide ideation test (mean score 9.4 vs. 5.2 points, p<0.001), but also significant in the CAQs of hypochondric behavior, apathy and schizophrenia (p<0.01) as well as in CAQs of low energy, guiltiness and psychological deviation (p<0.05). Further details are given in Table 1.

Patients with depression and with or without ideation of suicide. Gender, age and results of psychological testing.

| Pts. with ideation of suicide | Pts. without ideation of suicide | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 20 | 19 |

| Gender (female:male) | 10:10 | 12:7 |

| Age (years) | 29.2 (19.6–45.2) | 30.42 (22.8–47.1) |

| Mini-mental | 34.0±1.1 | 33.4±1.4 |

| 5-Digits inhibition | 5.1±1.7 | 4.8±2.7 |

| 5-Digits flexibility | 4.7±2.3 | 4.1±2.4 |

| TESEN execution | 4.3±1.7 | 4.3±2.2 |

| TESEN velocity | 4.6±2.0 | 4.5±2.0 |

| TESEN precision | 4.7±1.9 | 5.6±1.7 |

| CAQ hypochondriasis | 8.7±1.6** | 6.8±1.7** |

| CAQ suicide ideation | 9.4±0.8*** | 5.2±1.0*** |

| CAQ agitation | 5.9±2.5 | 6.9±1.6 |

| CAQ anxiety | 7.5±1.9 | 6.3±2.2 |

| CAQ low energy | 8.9±1.7* | 7.4±1.9* |

| CAQ guiltiness | 8.0±1.9* | 6.3±2.1* |

| CAQ apathy | 8.0±1.5** | 6.4±1.6** |

| CAQ paranoia | 7.6±1.7 | 6.7±1.8 |

| CAQ psychopathic dev. | 4.8±2.2 | 5.9±1.1 |

| CAQ schizophrenia | 8.3±1.6** | 6.3±2.0** |

| CAQ psychasthenia | 7.2±2.0 | 5.9±2.0 |

| CAQ psychological deviation | 7.9±2.0* | 6.1±2.0* |

Age- and mini-mental score-corrected evaluation of T1-weighted data using CAT as described above, did not show significant differences of grey matter density or cortical thickness between all three groups.

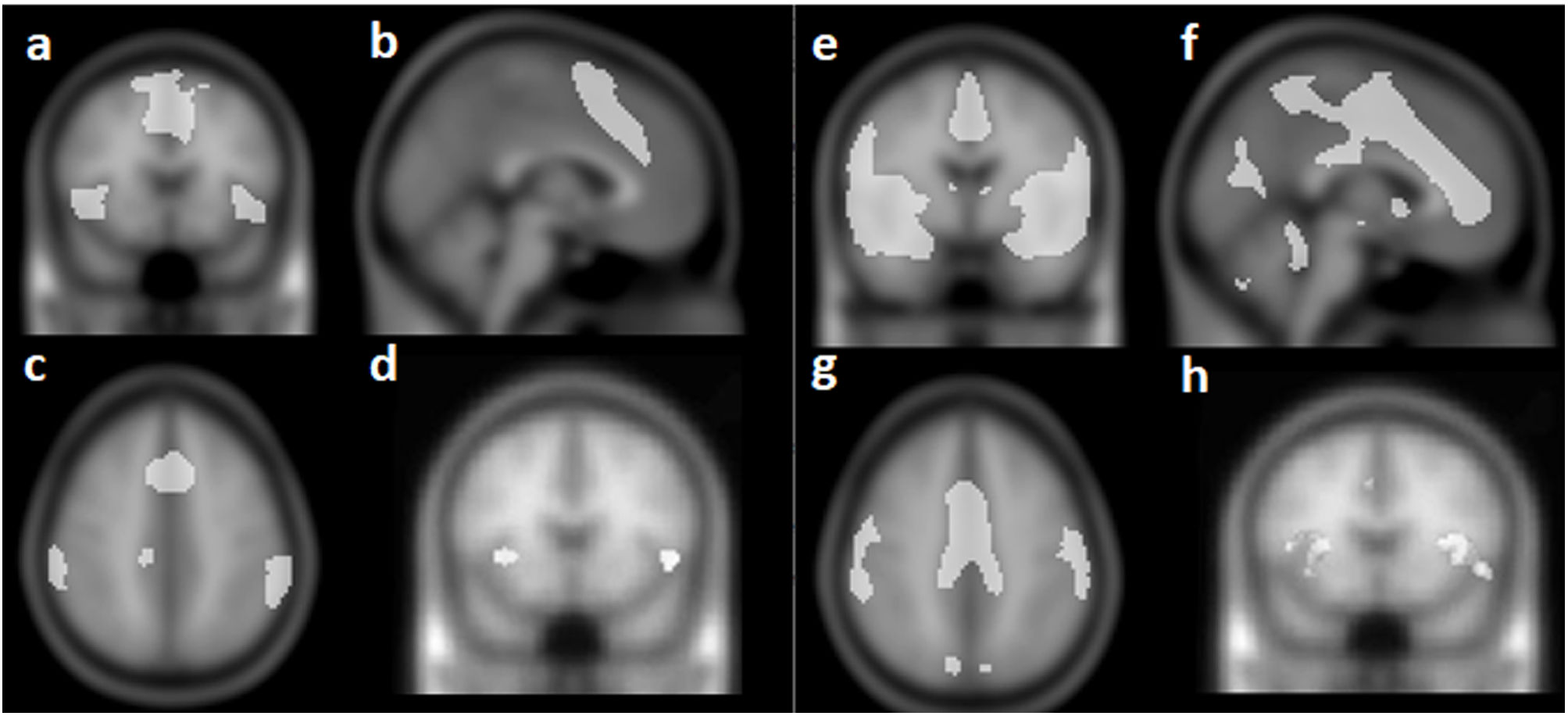

Functional MRI of activation during moral decision makingCerebral activation during making moral decisionsEvaluation of combined data of all participants revealed significant (p<0.001, FWE corrected) activations during taking moral decisions prefrontal, fronto-orbital, parietal, insular and thalamic areas of both sides as well as in the cerebellum, which corresponded in well to areas of the salience network (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Within these areas of activation, some peaks showed significant correlations (p<0.05, uncorrected) to the score of suicidality: fronto-opercular and dorso-anterior insular areas of both sides correlated negatively, whereas positive correlations were found in prefrontal and parietal areas and in both thalami.

Cerebral areas activated by moral paradigm and areas included in component 13 of independent component analysis (ICA). One sample t-test over 55 participants, significance at cluster level, p<0.001, corrected for multiple comparison (FEW).

| Cerebral areas | Areas activation by moral paradigm | Areas included in component 13 of ICA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates x,y,z | Number of voxels | Correlation to suicidality* | Coordinates x,y,z | Number of voxels | Correlation to suicidality* | |

| Lobulus Parietal inf. L | −46, −20, 54 | 4746 | ||||

| Cerebellum sup. R | 24, −50, −22 | 4070 | ||||

| Fronto-medial G. R+L | −2, 2, 54 | 3257 | 0.002 (pos.) | −2, 2, 54 | 3257 | 0.001 (neg.) |

| Lobulus Parietal Inf. R | 54, −54, 38 | 3161 | 0.007 (pos.) | |||

| Fronto-operc. A.+Insula R | 44, 10, 4 | 1519 | 0.006 (neg.) | −40, 0, 2 | 16119 | <0.001 (neg.) |

| Thalamus R+L | 10, −14, −8 | 1763 | 0.002 (pos.) | −10, −24, −0 | 1947 | 0.001 (pos.) |

| Fronto-operc. A.+Insula L | −42, −2, 6 | 154 | 0.029 (neg.) | 44, −10, −4 | 18253 | 0.002 (neg.) |

| Cerebellum Sup. L | −26, −56, −20 | 586 | 8, −48, −20 | 583 | ||

| Cingulate Post. L | 4, −28, 26 | 271 | ||||

| Mid-frontal G. L | 32, 30, 24 | 867 | 0.002 (pos.) | |||

| Lobulus Parietal Sup. L | 4, −72, 46 | 46 | ||||

| Cerebellum Lat. R | −44, −50, −22 | 463 | ||||

Areas of activation during application of moral paradigm (a–d) and of areas included in component 13 of independent component analysis of resting state data (e–h). One sample t-test (a–c and e–g); significance on cluster level of p<0.001, FEW corrected). Negative correlation of anterior insulae to suicidality (d and h) with significance on peak level, p<0.05, uncorrected.

ICA analysis of data measured during resting state revealed one component (component 13, Table 2 and Fig. 2) with a nearly identical cerebral representation as the salience network shown in Fig. 1 including those areas of component 13 with a negative correlation to the score of suicidality: the anterior insulae.

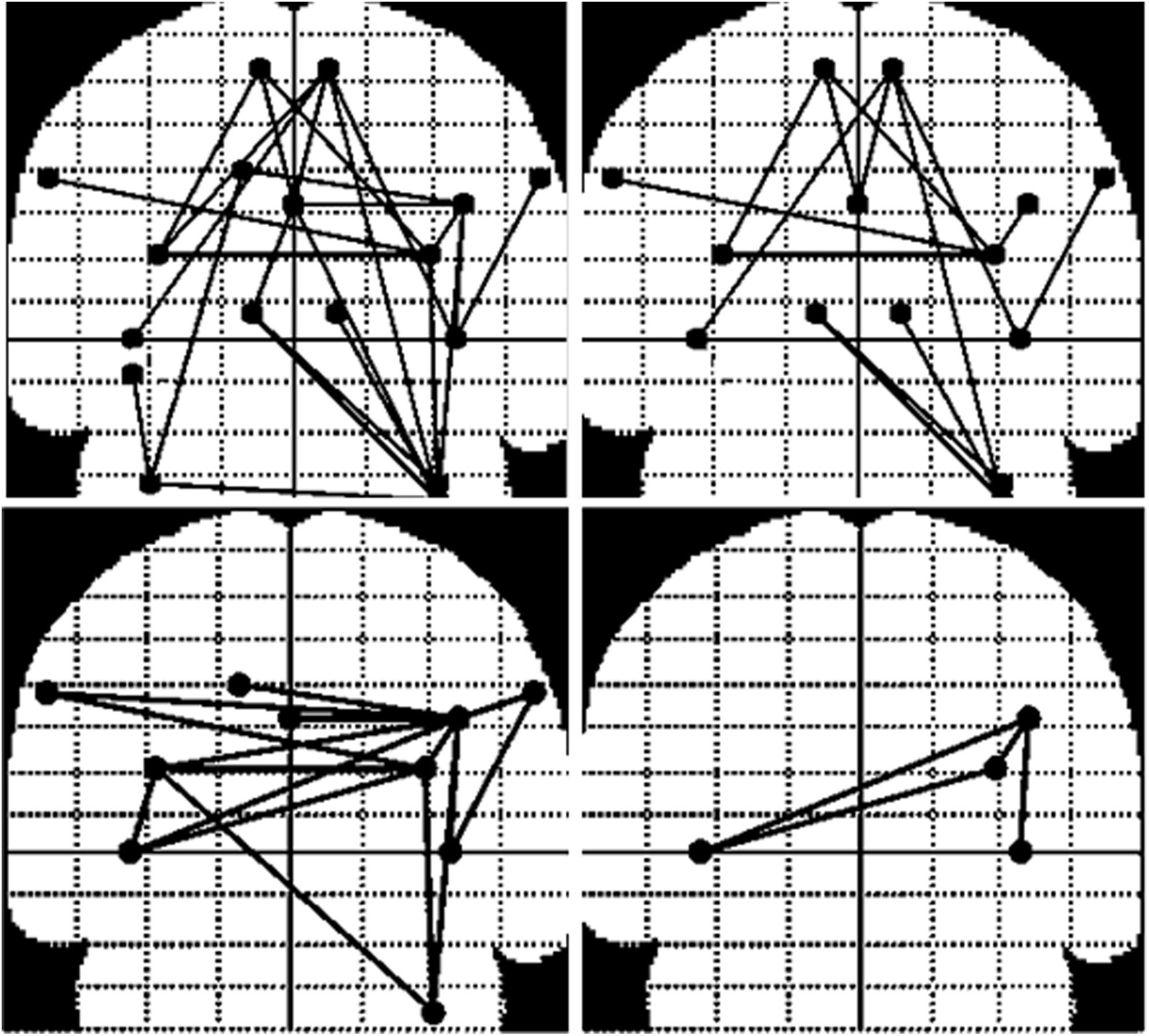

Connectivity of these ROIs within the salience network as evaluated by NBS, correlated significantly (p<0.05, NBS corrected) and negatively the score of suicidality, with highest values of connections between the midfrontal gyri and the fronto-opercular-insular areas of both hemispheres to central and parietal areas (Table 3 and Fig. 3). A significantly higher connectivity with special involvement of connections involving both insulae was shown by 2-sample t-test comparing resting state salience networks of patients without suicide ideas to those with ideation of suicide.

Connections between ROIs of salience network as shown in Fig. 1b, which correlate significantly (p<0.05, NBS-corrected) and negatively to score of suicidality, in NBS analysis at threshold of t=5.0. T-values of NBS ANCOVA statistics, are listed in the left part of the table.

| Connections correlating neg. to suicidality | T-values of NBS | Connections stronger in patients without suicide ideas | T-values of NBS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Midfrontal G. R – Midfrontal G. L | 5.96 | ||

| Midfrontal G. R – Central Area R | 7.11 | ||

| Midfrontal G. L – Lobulus Parietalis Inf. R | 5.48 | Midfrontal G. L – Insula R | 3.17 |

| Midfrontal G. L – Central Area R | 9.52 | ||

| Midfrontal G. L – Frontolateral Area L | 6.11 | Midfrontal G. L – Frontolateral Area L | 3.23 |

| Fronto-medial Area – Central Area R | 5.08 | ||

| Fronto-medial Area – Central Area L | 5.69 | ||

| Insula R – Central Area L | 5.01 | Insula R – Frontolateral Area L | 4.22 |

| Insula L – Central Area L | 7.66 | ||

| Insula L – Lobulus Parietalis Inf. L | 7.51 | Insula L – Frontolateral Area L | 3.32 |

| Thalamus R – Cerebellum Sup. L | 5.7 | ||

| Thalamus R – Cerebellum Lat. L | 6.01 | ||

| Thalamus L – Cerebellum Lat. L | 7.13 | ||

| Central Area L – Cerebellum Lat. L | 7.8 | ||

| Insula R – Amygdala R | 5.34 |

Connections, which show stronger correlations (p<0.05, NBS-corrected) in depressive patients without ideas of suicide as compared to those with those ideas in NBS analysis at threshold of t=3.0, T-values of NBS 2-sample t-test, are listed in the right part of the table.

Correlation of connectivity within salience network to suicidality (upper images). Evaluation by NBS using Ancova F-test as included in the NBS Program. At a lower threshold of t=4 (upper left image), 26 connections between 21 ROIs, and at a higher threshold of t=5 (upper right image), 15 connections between 15 ROIs show significant negative correlation (p<0.05, NBS-corrected). The latter 15 connections are listed in Table 3.

Difference of connectivity within salience network between patients without ideation of suicide as compared to those with ideas of suicide (lower images). Evaluation by NBS using 2 sample t-test. At a lower threshold of t=2 (lower left image), 16 connections between 10 ROIs (left image) and at a higher threshold of t=3 (lower right image), 4 connections between 4 ROIs (right image) show significantly different negative correlation (p<0.05, NBS-corrected). The latter 4 connections are listed in Table 3.

For the first time, the areas of activations involved in moral decision-making was examined in depressive patients with ideation of suicide and compared to the activity of the salience network during resting state in the same individual. An important finding of the present study is the close similarity of this “moral decision making network” measured during an activation paradigm to the salience network measured during resting state conditions, as shown in Figs. 1–3, and their correlation to the score of suicidality.

Decisions making in a more general sense without emotions, usually involves the dorsal attention network anchored in the frontal eye field and intraparietal sulcus and the left and right lateral fronto-parietal central executive networks.13 Those more dorsal situated areas were not activated by our paradigm as strong as expected, and we did not see important activations of the occipito-temporal regions.

In the present study, activation of salience-related areas as the anterior section of the insulae and adjacent ventro-lateral prefrontal cortices as well as frontal midline structures supervened. However, a clear distinction from the cingulo-opercular task control network as described by Dosenbach et al.14 was not possible. This network is supposed to be engaged more in “tonic alertness”15 than in maintenance of homeostasis or in switching to salient tasks in case of changing external conditions. These latter activities are attributed to ventral parts of the anterior insula.16 This region is also thought to be related to emotional awareness, possibly due to the presence of so-called von Economo neurons.7

Different responses of selected areas within this “moral” network in the sense of activations and deactivations have been reported before: Frontal and central midline areas have been shown to correlate with insular activity positively (anterior part) or negatively (posterior part) in moral dilemmas17 and to be more active in harm/welfare based decisions relative to social-conventional transgressions.18 A variety of experimental, social and individual factors will strongly influence the distribution of activated areas within this “moral” network, e. g. the choice of the moral decision paradigm or the superordinate moral concepts of the individual.19 The ventro-medial prefrontal cortex has been reported to serve as an area to integrate emotional and utilitarian appraisals of moral dilemmas.20

The importance of the participation of areas of the salience networks in moral decision making in patients with major depression is underlined by the significant correlation of some peaks of activation clusters to the score of suicidality. The negative correlation of the activation within the fronto-opercular and mainly the anterior insular cortex to presence of suicide ideas found in our group corresponds well to the finding of a lower activation of this area to stimuli of positive moral valence in patients with unipolar depression.21 The insula may play important roles in switching between ventral and dorsal prefrontal cortex systems, which may contribute to the transition from suicide thoughts to behaviors.22 In our study, other areas, mainly the fronto-medial and -lateral areas, the inferior parietal lobuli and thalamus, correlated positively to suicidal imagination. Fronto-medial and more dorso-medial areas are known to be involved in processing of feelings of guilt, shame and sadness, whereas the activation of other ones mentioned above corresponds more to the success or failure of live-saving moral decisions.23,24

A second important finding of this study was the reduced connectivity in depressive patients with ideas of suicide as compared to those without suicidal ideation and the negative correlation of connectivity within this network to the score of suicidality as shown in Fig. 3. Reduction of connectivity is a general finding in resting state networks25 and as in our study, reduction of connectivity usually includes the amygdala.10 It was more pronounced in patients with ideation of suicide and in suicide attempters.26 A recent meta-analysis confirmed previous studies showing overall weakened functional within-network connectivity during resting state, mainly affecting the central executive network.27 It has been suggested to use network coherence as a predictor of responsiveness to treatment in major depression.28 In a longitudinal study,29 intra-network coherence improved together with reduction of suicide ideation. It could be restored, together with clinical improvement, by training of attentional bias modification.30

The strong influence of subjective moral concepts on decision making is well-known and has been substantiated by activation studies using word pairs related to abstract values. Persons with a predominant collectivistic (altruistic) value system applied a “balancing and weighing” strategy, recruiting brain regions of rostral inferior and intraparietal, and midcingular and frontal cortex. Conversely, subjects with mainly individualistic (egocentric) value preferences applied a “fight-and-flight” strategy by recruiting the left amygdale. If subjects experience a value conflict when rejecting an alternative congruent to their own predominant value preference, comparable brain regions are activated as found in actual moral dilemma situations, i.e., midcingular and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.31,32 In suicide attempters, impaired decision-making and social difficulties have been related to prefrontal areas by functional MRI, which showed impaired valuation processing for signals of social threat, sadness and reward.33 Similar relations between moral competence and structural and functional connectivity have been shown by previous activation studies, mainly concerning prefrontal, insular and cingular areas.34

In our study, cerebral activation during moral decision making did not show significant differences between groups, but results over all participants were in accordance with previous studies demonstrating increased activity implicated in morality in prefrontal, insular and cingular cortices.35 Similar areas have been shown to activate during evaluation of truth and falsity of religious vs. non-religious propositions. A comparison of both stimulus categories suggested that religious thinking is more associated with brain regions that govern emotion, self-representation, and cognitive conflict, while thinking about ordinary facts is more reliant upon memory retrieval networks.36 Self-referential processing induced increased activity in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex for non-religious participants, but in the dorsal MPFC for Christian participants. The dorsal MPFC activity was positively correlated with the rating scores of the importance of Jesus’ judgment in subjective evaluation of a person's personality.37,38

In contrast to previous reports,39 which demonstrated a trend of the “suicidal brain” to reductions of grey and white matter mainly of the frontal areas, we did not see significant reductions of grey matter volume or of cortical thickness. One explanation – apart from the limited size of the groups included – may be the fact that not all patients with suicide ideation had shown active suicide behavior before. As compared to depressive patients without a history of suicide attempts, the prefrontal cortical reduction was significantly more pronounced in the group of suicide attempters.8,40

ConclusionBecause the cerebral areas activated during a moral decision paradigm are nearly identical to the salience network seen in our study and because selected areas within this network, mainly the anterior parts of the insula, correlate negatively to suicidality, a special training using moral tasks might help to reduce suicidality in depressive patients. Further studies with larger patient samples and inclusion of a rating scale related to morality and religiosity are needed to evaluate the impact of strong Christian belief as found in the Dominican Republic on protection from suicide in depression.

Ethical approvalThe study outline had been approved by the CEDIMAT ethic committee (CEI 289) and informed consent had been received by all participants before entering into the study.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestNone declared.

The poster “Stoeter P, Morillo J, Polanco C, Oviedo J, Speckter H. Structural and functional deviations in magnetic resonance imaging in depressed patients with suicidal ideation.” was presented at the Congress of the Dominican Society of Neurology and Neurosurgery 2020, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic.