Worldwide, because of the demographic transition, the proportion of older adults has increased, which has been reflected in an increase in the prevalence of major neurocognitive disorder (MND). This phenomenon is especially important in low- and middle-income countries such as Colombia, given the high economic and social costs it entails. The objective was to analyse the association between socioeconomic variables with the presence of cognitive impairment in Colombian older adults.

MethodsThe records of 23,694 adults over 60 years-of-age surveyed for SABE Colombia 2015, that took a stratified sample by conglomerates and were representative of the adult population over 60 years-of-age. This instrument assessed cognitive impairment using the abbreviated version of the Minimental (AMMSE) and collected information on multiple socioeconomic variables.

Results19.7% of the older adults included in the survey were reviewed with cognitive impairment by presenting a score <13 in the AMMSE. There was a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment in women (21.5%) than in men (17.5%). The socioeconomic variables were shown to impact the prevalence of deterioration, especially being currently working (OR = 2.74; 95%CI, 2.43−3.09) as a risk factor and having attended primary school as a protective factor (OR = 0.30; 95%CI, 0.28−0.32), differentially according to gender.

ConclusionsAn association between socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors with cognitive impairment in Colombian older adults was evidenced. Despite the above, a differential impact dependent on sex is suggested.

Producto de la transición demográfica, en todo el mundo ha aumentado la proporción de adultos mayores, lo que se refleja en un aumento de la prevalencia del trastorno neurocognitivo mayor (TNM). Este fenómeno resulta especialmente importante en países de ingresos bajos y medios como Colombia, dados los importantes costos económicos y sociales que acarrea. El objetivo es analizar la asociación entre variables socioeconómicas y sociodemográficas y el deterioro cognitivo en adultos mayores colombianos.

MétodosSe evaluaron los registros de 23.694 adultos mayores de 60 años encuestados para SABE Colombia 2015, que utilizó un muestreo estratificado por conglomerados y fue representativa de la población adulta mayor de 60 años. Este instrumento evaluó el deterioro cognitivo mediante la versión abreviada del Mini Mental (AMMSE) y recolectó información sobre múltiples variables socioeconómicas y sociodemográficas.

ResultadosSe consideró con deterioro cognitivo al 19,7% de los adultos mayores incluidos en la encuesta con puntuaciones < 13 en el AMMSE. Hubo una mayor prevalencia de deterioro cognitivo en mujeres (21,5%) que en varones (17,5%). Las variables socioeconómicas mostraron un impacto en la prevalencia de deterioro, en especial estar trabajando actualmente (OR = 2,74; IC95%, 2,43–3,09) como factor de riesgo y haber cursado al menos primaria como factor protector (OR = 0,30; IC95%, 0,28–0,32). Esta asociación se comportó de manera diferencial según el sexo.

ConclusionesSe evidencio una asociación entre factores socioeconómicos y sociodemográficos con el deterioro cognitivo en adultos mayores colombianos. Pese a lo anterior, se sugiere un impacto diferencial dependiente del sexo.

In recent years, there has been a considerable change in health dynamics around the world due to the ageing of the population, leading to lower fertility and mortality rates and a sustained increase in the world's older adult population.1 The situation in developing countries is especially striking; according to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are currently 400 million people over 60 years of age who, by 2025, will represent 70% of the world's older adult population.2

In Colombia, according to data from the National Population and Housing Census carried out by the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE) [National Administrative Department of Statistics], 12.27% of the national population is over 60 years old, contrasting with data from 2005, when it was 8.98%.3 These changes in the age structure are associated with a higher prevalence of chronic diseases, including cognitive impairment spectrum disorders.1

Cognitive impairment is a broad spectrum of conditions where there is a decline in cognitive functions greater than expected for age. It is classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), into two separate conditions that are part of the same disease continuum: minor neurocognitive disorder or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and major neurocognitive disorder (MND).4 The difference between the two is that MCI does not affect daily activities, while MND does. In Colombia, 238,583 people are reported to have MND according to the 2018 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) report, leading to 158,120 years lost due to disability.5 With respect to MCI, a worldwide prevalence is estimated at 5%–7.1% according to an analysis published by the Cohort Studies of Memory in an International Consortium (COSMIC).6

There are multiple risk factors associated with MND, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and smoking. These risk factors act regardless of age, race, gender and educational level. Subjects with these four risk factors are twice as likely to suffer from MND. In addition, each of these factors individually increases the risk of suffering from MCI by 20%–40%.7,8

Although many studies seek to relate different risk factors with cognitive function, few focus on socioeconomic and sociodemographic variables. An association between socioeconomic vulnerability and development of MND and different findings depending on gender has been described in the South Korean population; not having worked affected men more markedly, and a lower educational level affected women.9 A study carried out in the United States showed that higher income and higher educational level are associated with lower risk of MND.10 Despite the above, given the complexity of these variables, in which multiple social actors participate, it is difficult to carry out intervention studies, and long follow-ups are required to detect differences. Furthermore, there is not enough evidence in Latin America to support these associations, which is of great importance considering the growth of the older adult population.

It is essential to protect the cognitive capacity of older adults in society and promote research in this field.11 Although there are currently no treatments that reverse the course of this disease, it is well-known that some prevention strategies can delay its onset.12,13 Among measures demonstrating the greatest impact are those associated with the social determinants of health, especially socioeconomic factors.9 In view of the above, with this study we sought to evaluate the association between socioeconomic and sociodemographic risk factors and cognitive impairment in older Colombian adults, and determine whether or not these act differently depending on gender.

MethodsObservational, analytical cross-sectional study. For the study, we used data from the Encuesta Nacional de Salud, Bienestar y Envejecimiento (SABE Colombia 2015) [2015 Colombian national survey on Health, Well-being and Ageing], which took a representative sample of the population of adults over 60 years of age in Colombia. The data were collected in 2014 using probabilistic cluster, stratified and multi-stage sampling. The trained interviewer applied a survey-type instrument to the selected individuals which included sections on health, family, cognition, work history and economic conditions.14

To be representative nationally, the survey sample calculation was carried out using a population of 4964,793 based on DANE projections, establishing a minimum expected proportion of 0.03, a design effect of 1, 2, a no response rate of 20% and a relative error of 0.05.15 From this, 30,691 older adults were selected; of them, 23,694 participants from rural and urban areas responded to the instrument.

InstrumentThe SABE survey evaluated cognitive status through the abbreviated version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), developed and validated in the Chilean population of Concepción, which was part of the World Health Organization's “Age-Related Dementia” study in 1990 and 1992.16,17 The instrument has a maximum score of 19 points, with the cut-off point for detecting cognitive impairment being a score <13 points, with a sensitivity of 93.8% and a specificity of 93.9%.14,16,18

It also assessed the following variables which have shown a relationship with cognitive impairment, the information for which was provided by the respondents to the survey, or a guardian if they were not able to respond, divided into two groups for the purposes of the analysis:

- •

Sociodemographic and socioeconomic: gender; marital status (with a partner or without a partner); age; area of current residence (rural or urban); regular physical activity; considering oneself as displaced by violence; whether the individual lives alone or with a relative; socioeconomic stratum of the home (high, medium-low); level of education finished; current employment status; and current monthly income.

- •

Comorbidities: subjects' responses to whether they had ever been diagnosed with stroke; high blood pressure; diabetes; acute myocardial infarction or other cardiovascular complications were included.

STATA SE version 16 was used for the statistical analysis. The dependent variable was the MMSE classification; the independent ones, the socioeconomic and sociodemographic variables, and the confounding variables, the comorbidities. The data were evaluated using parametric or non-parametric statistics, depending on the nature and distribution of the variables.

Bivariate analysis was performed with the objective of calculating crude measures of association with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) and their respective statistical significance. Based on the results, with the variables which were statistically significant or had significant support in the literature, a multivariate binomial logistic regression model was built to control confusion. The independent variable was the category in which the subject belongs according to the result of the MMSE. For this, the assumptions required by a logistic regression model were assessed, and confusion was controlled by adding other variables. Several models were constructed and assessed using likelihood ratio (LR), pseudo-R2 and Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The model that achieved the best parameters was selected, and then the same process was repeated with two different models according to gender, since the evidence indicates some gender-based differences in the effects of some variables on cognition.

Ethical considerationsThis study complies with the regulations established by the Declaration of Helsinki, Fortaleza,19 and Colombian Resolution 8430 of 1993 for studies in humans20 and was endorsed by the Universidad CES Independent Ethics Committee for research in humans. The study also complied with Law 1581 of 2013, ensuring anonymity of individuals, and permission to use the survey data was obtained from the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection Directorate of Epidemiology and Demography.

ResultsThere were 23,694 records: 57.3% women and 42.7% men, with an average age of 70 ± 8.2 years; 81.6% lived in a home classified as low stratum; 87.3% of respondents had worked at some point in their lives and 33.7% were working at the time of the survey. The majority of respondents (80.7%) had a monthly income less than three minimum wages, and 59.73% belonged to the subsidised healthcare system. Some 78.9% had only finished primary education and 22% did not have access to formal education. A majority of respondents were married or in a common law union (53%) and lived in urban areas of the country (72.5%).

According to the MMSE, 19.7% were classified as having neurocognitive impairment (21.5% of women and 17.5% of men). Individuals with cognitive impairment were older on average, lived in rural areas, reported living with a companion, were more frequently considered victims of forced displacement, and had a lower rate of physical activity and a higher prevalence of comorbidities.

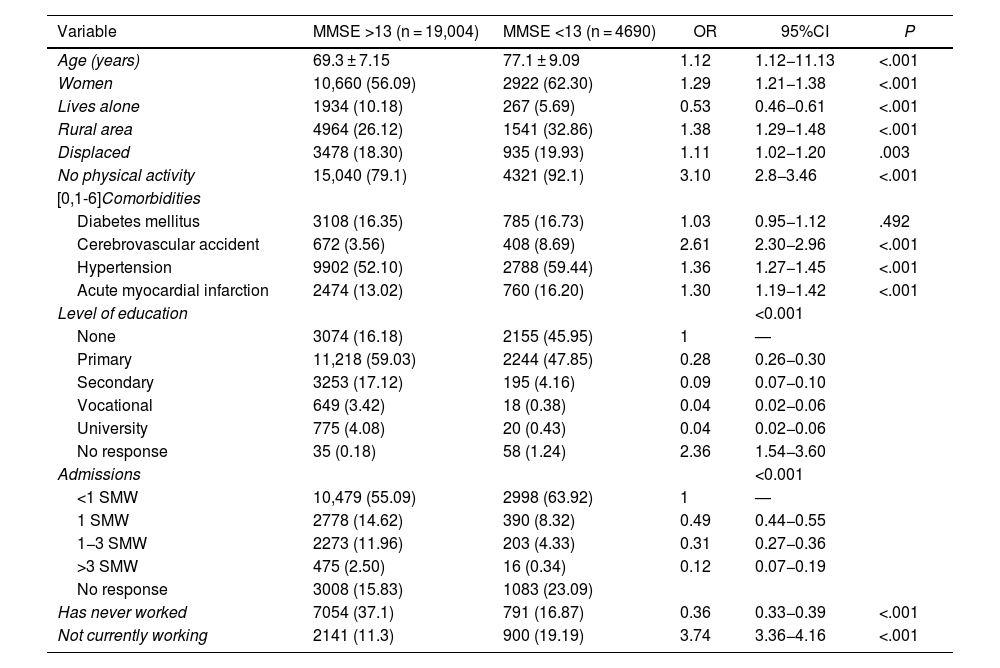

The comorbidities assessed were associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment, with the exception of diabetes mellitus (odds ratio [OR] = 1.03; 95%CI, 0.95−1.12; P = .49). It was also found that a monthly income greater than 1 minimum wage decreased the probability of cognitive deterioration (OR = 0.49; 95%CI, 0.44−0.55; P ≤ .001), as did having a higher educational level (OR = 0.04; 95%CI, 0.02−0.06; P < .001) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the sample.

| Variable | MMSE >13 (n = 19,004) | MMSE <13 (n = 4690) | OR | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.3 ± 7.15 | 77.1 ± 9.09 | 1.12 | 1.12−11.13 | <.001 |

| Women | 10,660 (56.09) | 2922 (62.30) | 1.29 | 1.21−1.38 | <.001 |

| Lives alone | 1934 (10.18) | 267 (5.69) | 0.53 | 0.46−0.61 | <.001 |

| Rural area | 4964 (26.12) | 1541 (32.86) | 1.38 | 1.29−1.48 | <.001 |

| Displaced | 3478 (18.30) | 935 (19.93) | 1.11 | 1.02−1.20 | .003 |

| No physical activity | 15,040 (79.1) | 4321 (92.1) | 3.10 | 2.8−3.46 | <.001 |

| [0,1-6]Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3108 (16.35) | 785 (16.73) | 1.03 | 0.95−1.12 | .492 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 672 (3.56) | 408 (8.69) | 2.61 | 2.30−2.96 | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 9902 (52.10) | 2788 (59.44) | 1.36 | 1.27−1.45 | <.001 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2474 (13.02) | 760 (16.20) | 1.30 | 1.19−1.42 | <.001 |

| Level of education | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 3074 (16.18) | 2155 (45.95) | 1 | — | |

| Primary | 11,218 (59.03) | 2244 (47.85) | 0.28 | 0.26−0.30 | |

| Secondary | 3253 (17.12) | 195 (4.16) | 0.09 | 0.07−0.10 | |

| Vocational | 649 (3.42) | 18 (0.38) | 0.04 | 0.02−0.06 | |

| University | 775 (4.08) | 20 (0.43) | 0.04 | 0.02−0.06 | |

| No response | 35 (0.18) | 58 (1.24) | 2.36 | 1.54−3.60 | |

| Admissions | <0.001 | ||||

| <1 SMW | 10,479 (55.09) | 2998 (63.92) | 1 | — | |

| 1 SMW | 2778 (14.62) | 390 (8.32) | 0.49 | 0.44−0.55 | |

| 1−3 SMW | 2273 (11.96) | 203 (4.33) | 0.31 | 0.27−0.36 | |

| >3 SMW | 475 (2.50) | 16 (0.34) | 0.12 | 0.07−0.19 | |

| No response | 3008 (15.83) | 1083 (23.09) | |||

| Has never worked | 7054 (37.1) | 791 (16.87) | 0.36 | 0.33−0.39 | <.001 |

| Not currently working | 2141 (11.3) | 900 (19.19) | 3.74 | 3.36−4.16 | <.001 |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: raw odds ratio.

Values are expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

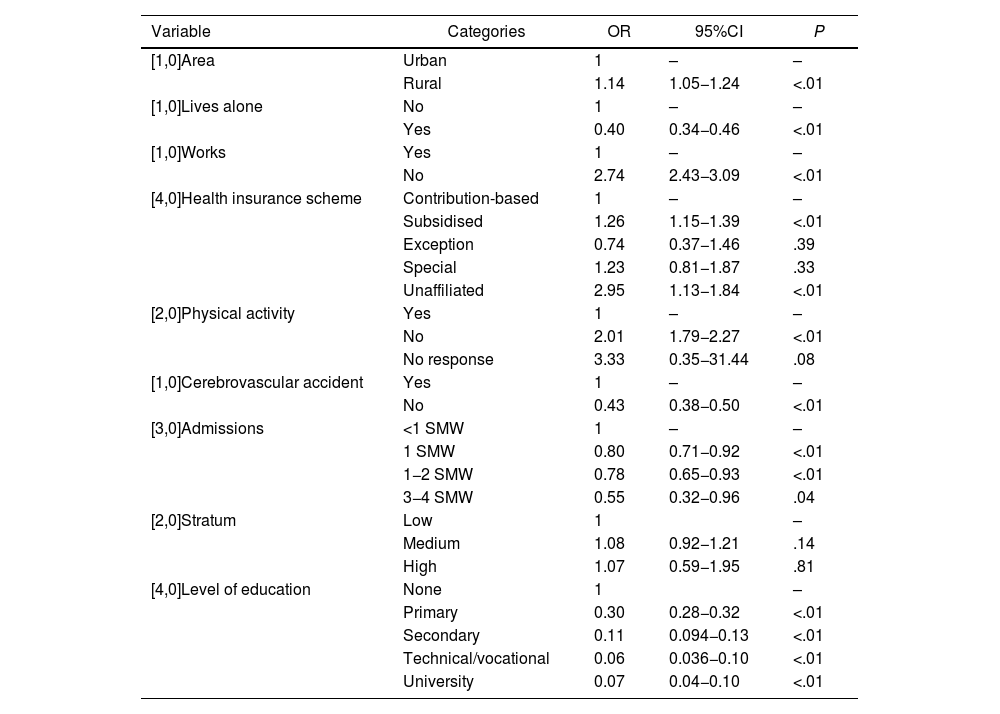

Multivariate binomial logistic regression analyses showed a significant association between multiple independent variables and cognitive impairment (Table 2). This model included the variables shown to be significant in previous analyses. Regarding the goodness-of-fit and the assessment of the model, we obtained P = .46 and pseudo-R2 of 17% applying the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Final adjusted model.

| Variable | Categories | OR | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1,0]Area | Urban | 1 | – | – |

| Rural | 1.14 | 1.05−1.24 | <.01 | |

| [1,0]Lives alone | No | 1 | – | – |

| Yes | 0.40 | 0.34−0.46 | <.01 | |

| [1,0]Works | Yes | 1 | – | – |

| No | 2.74 | 2.43−3.09 | <.01 | |

| [4,0]Health insurance scheme | Contribution-based | 1 | – | – |

| Subsidised | 1.26 | 1.15−1.39 | <.01 | |

| Exception | 0.74 | 0.37−1.46 | .39 | |

| Special | 1.23 | 0.81−1.87 | .33 | |

| Unaffiliated | 2.95 | 1.13−1.84 | <.01 | |

| [2,0]Physical activity | Yes | 1 | – | – |

| No | 2.01 | 1.79−2.27 | <.01 | |

| No response | 3.33 | 0.35−31.44 | .08 | |

| [1,0]Cerebrovascular accident | Yes | 1 | – | – |

| No | 0.43 | 0.38−0.50 | <.01 | |

| [3,0]Admissions | <1 SMW | 1 | – | – |

| 1 SMW | 0.80 | 0.71−0.92 | <.01 | |

| 1−2 SMW | 0.78 | 0.65−0.93 | <.01 | |

| 3−4 SMW | 0.55 | 0.32−0.96 | .04 | |

| [2,0]Stratum | Low | 1 | – | |

| Medium | 1.08 | 0.92−1.21 | .14 | |

| High | 1.07 | 0.59−1.95 | .81 | |

| [4,0]Level of education | None | 1 | – | |

| Primary | 0.30 | 0.28−0.32 | <.01 | |

| Secondary | 0.11 | 0.094−0.13 | <.01 | |

| Technical/vocational | 0.06 | 0.036−0.10 | <.01 | |

| University | 0.07 | 0.04−0.10 | <.01 |

In the model, living alone was found to be a protective factor against cognitive decline (OR = 0.40; 95%CI, 0.34−0.46; P < .05). However, living in a rural area (OR = 1.14; 95%CI, 1.05−1.24; P = .001), doing no type of physical activity (OR = 2.01; 95%CI, 1.78–2.27) and belonging to the subsidised healthcare system (OR = 1.26; 95%CI, 1.15−1.39; P < .05) were all risk factors.

With respect to socioeconomic variables, higher educational levels acted as a protective factor against cognitive deterioration; lower risk was found in those with a university degree (OR = 0.07; 95%CI, 0.04−0.11) or technical/vocational training (OR = 0.06; 95%CI, 0.04−0.10). The higher the income, the greater the reduction in the risk of cognitive impairment (Table 2).

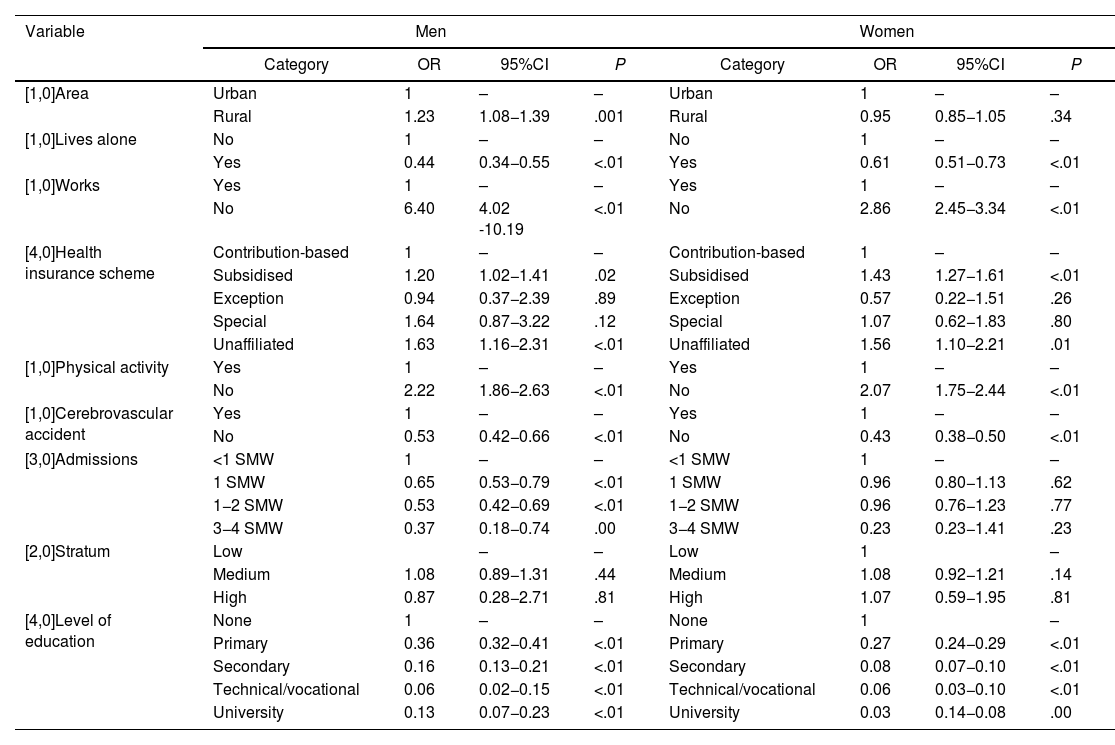

The model by gender showed different impacts of some variables on the risk of cognitive impairment. In women, not working (OR = 2.86; 95%CI, 2.45−3.34) and not doing physical activity (OR = 2.07; 95%CI, 1.75−2.44) were risk factors. For men, unlike women, socioeconomic status and monthly income reduce the risk in a statistically significant way. The risk of cognitive decline in men was higher among the unemployed (OR = 6.40; 95%CI, 4.02–10.19), those resident in rural areas (OR = 1.23; 95%CI, 1.08−1.39) and those who did not do physical activity (OR = 2.22; 95%CI, 1.86−2.63) (Table 3).

Sociodemographic risk factors by gender.

| Variable | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | OR | 95%CI | P | Category | OR | 95%CI | P | |

| [1,0]Area | Urban | 1 | – | – | Urban | 1 | – | – |

| Rural | 1.23 | 1.08−1.39 | .001 | Rural | 0.95 | 0.85−1.05 | .34 | |

| [1,0]Lives alone | No | 1 | – | – | No | 1 | – | – |

| Yes | 0.44 | 0.34−0.55 | <.01 | Yes | 0.61 | 0.51−0.73 | <.01 | |

| [1,0]Works | Yes | 1 | – | – | Yes | 1 | – | – |

| No | 6.40 | 4.02 -10.19 | <.01 | No | 2.86 | 2.45−3.34 | <.01 | |

| [4,0]Health insurance scheme | Contribution-based | 1 | – | – | Contribution-based | 1 | – | – |

| Subsidised | 1.20 | 1.02−1.41 | .02 | Subsidised | 1.43 | 1.27−1.61 | <.01 | |

| Exception | 0.94 | 0.37−2.39 | .89 | Exception | 0.57 | 0.22−1.51 | .26 | |

| Special | 1.64 | 0.87−3.22 | .12 | Special | 1.07 | 0.62−1.83 | .80 | |

| Unaffiliated | 1.63 | 1.16−2.31 | <.01 | Unaffiliated | 1.56 | 1.10−2.21 | .01 | |

| [1,0]Physical activity | Yes | 1 | – | – | Yes | 1 | – | – |

| No | 2.22 | 1.86−2.63 | <.01 | No | 2.07 | 1.75−2.44 | <.01 | |

| [1,0]Cerebrovascular accident | Yes | 1 | – | – | Yes | 1 | – | – |

| No | 0.53 | 0.42−0.66 | <.01 | No | 0.43 | 0.38−0.50 | <.01 | |

| [3,0]Admissions | <1 SMW | 1 | – | – | <1 SMW | 1 | – | – |

| 1 SMW | 0.65 | 0.53−0.79 | <.01 | 1 SMW | 0.96 | 0.80−1.13 | .62 | |

| 1−2 SMW | 0.53 | 0.42−0.69 | <.01 | 1−2 SMW | 0.96 | 0.76−1.23 | .77 | |

| 3−4 SMW | 0.37 | 0.18−0.74 | .00 | 3−4 SMW | 0.23 | 0.23−1.41 | .23 | |

| [2,0]Stratum | Low | – | – | Low | 1 | – | ||

| Medium | 1.08 | 0.89−1.31 | .44 | Medium | 1.08 | 0.92−1.21 | .14 | |

| High | 0.87 | 0.28−2.71 | .81 | High | 1.07 | 0.59−1.95 | .81 | |

| [4,0]Level of education | None | 1 | – | – | None | 1 | – | |

| Primary | 0.36 | 0.32−0.41 | <.01 | Primary | 0.27 | 0.24−0.29 | <.01 | |

| Secondary | 0.16 | 0.13−0.21 | <.01 | Secondary | 0.08 | 0.07−0.10 | <.01 | |

| Technical/vocational | 0.06 | 0.02−0.15 | <.01 | Technical/vocational | 0.06 | 0.03−0.10 | <.01 | |

| University | 0.13 | 0.07−0.23 | <.01 | University | 0.03 | 0.14−0.08 | .00 | |

In the analysis of our sample, the prevalence of cognitive impairment was 19.7%, higher among women than men (21.5% compared to 17.5%), as has been seen in previous studies in other countries.21,22 However, logistic regression found no association between cognitive impairment and gender in the final model adjusted for other variables. This suggests that the differences could be due to factors associated with gender roles.

Among the main findings, the prevalence of cognitive impairment increases with some socioeconomic characteristics, such as living in a rural area (OR = 1.14; 95%CI, 1.05−1.24; P = .001). The relationship between living rurally and cognitive impairment had already been reported by other authors. Nunes et al.,23 with representative samples of older adults from rural and urban areas in northern Portugal, found a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment in rural areas, with a rural/urban prevalence ratio of 2.16. Similar results were obtained among inhabitants of rural and urban areas of the city of Ojiya, in Japan; 8.4% in rural areas compared to 2.9% in urban areas, and a three-times higher risk in rural (OR = 4.04; 95%CI, 1.54–10.62) compared to urban population.24

Socioeconomic conditions, such as higher monthly income (statutory minimum wage - SMW) and being in work, were associated with reductions in the risk of cognitive decline. At the educational level, widely considered a means to increase cognitive reserve (CR), it was found that a higher level of education reduces the risk of cognitive deterioration, and the lowest risk was found in those with a university degree (OR = 0.07; 95%CI, 0.04−0.11) or technical/vocational training (OR = 0.06; 95%CI, 0.04−0.10).

With regard to the education variable, the literature suggests that it acts as a protective factor against cognitive deterioration,9,12,13,23,25 in apparent association with greater CR, understood as a process of formation and activation of new synaptic connections and neural networks for better coping with environmental demands.26,27 In the study by Sattler et al.,25 it was found that having completed higher levels of education reduced the risk of Alzheimer's disease and cognitive decline by at least 85% compared to low educational levels (OR = 0.15; 95%CI, 0.06−0.38) and by 75% compared to intermediate levels of education (OR = 0.25; 95%CI, 0.13−0.49). A meta-analysis of observational studies published by Meng et al.28 in 2012 showed a 1.61-times greater risk (OR = 2.61; 95%CI, 2.21−3.07) of MND when comparing individuals with a low educational level and a high level.

One striking result was that in the multiple logistic regression model, no association was found between cognitive impairment and comorbidities such as hypertension, acute myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus. This contrasts with the literature, where these are well-established risk factors for deterioration. It is generally accepted that hypertension, circulatory problems, such as atherosclerosis causing AMI, and diabetes are significant modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline in old age.13,29

There are several reasons for these results; the first is that the data collection for this survey was subject to the memory of the individual or their family member in terms of determining comorbidities, given that cognitive impairment could interfere with how this information is reported. Another important aspect is that lower socioeconomic levels have been associated in the literature with a greater burden of chronic disease, especially cardiovascular disease and diabetes. However, in the general multivariate models, these associations could be controlled by including the socioeconomic variables.30,31

In the multivariate model by gender, some variables lost statistical significance when only housing area, socioeconomic stratum and current income were assessed in women. This result may reflect the gender roles of men and women in Colombia, where men usually assume the role of family breadwinner. Therefore, impairment in men's cognitive capacity is associated with monthly income and the area where their homes are located. In the same way, not working acted as a risk factor with greater strength of association in men (OR = 6.40; 95%CI, 4.02–10.19) than in women (OR = 2.86; 95%CI, 2.45−3.34), which again seems to be an association with gender roles.

Farné et al.32 found in 2017 that women in Colombia participate less in the labour market and have more responsibilities in the area of unpaid household chores. On average, men spend 8.1 h/day in paid work and women, 7.1 h. These differences seem to be explained because women have longer periods of inactivity or unemployment, as they reported, mainly due to family obligations. Lower pension coverage was also found for women (20.9%) than for men (30.9%). Women's pension allowances are lower, with their average monthly pension income being 80% of what men receive.

Given the limitations of this study, the use of a secondary source of information from which a secondary analysis was carried out limits the characteristics of collecting of the variables. In addition, some of the variables were self-reported by study participants, whose responses could have been affected by underlying cognitive impairment.

Among the main strengths, as the SABE 2015 survey used a representative sample of the overall older adult population of Colombia, the findings can be generalised to the entire population of older adults in Colombia.14,33 We also used a validated and adjusted instrument to screen for cognitive impairment in the older adult population (MMSE). This is especially important, given that the SABE survey has led to the application of similar instruments throughout the region, enabling comparison between countries with characteristics similar to Colombia.

ConclusionsThe results of this study demonstrate the importance of sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors in the risk of cognitive impairment. Among the main associated factors are educational level, living in a rural area and sedentary lifestyle. This reinforces the importance of plans designed to ensure access to education nationwide, as well as opportunities to pursue higher levels of education.

These elements are essential in rural areas, since they are more vulnerable to cognitive impairment and have lower schooling rates. Women's access to education and job opportunities are an important foundation for strategies to reduce the incidence of this condition.

Furthermore, given the impact of comorbidities on the development of cognitive impairment and the protective role that physical activity plays, it is essential to promote initiatives that focus on healthy lifestyles. Such initiatives could help reduce the prevalence of cardiovascular disease and so reduce the risk factors for cognitive impairment in older adults.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This article is based on the academic thesis Asociación entre el deterioro cognitivo y factores socioeconómicos en adultos mayores colombianos [Association between cognitive impairment and socioeconomic factors in Colombian older adults]/SABE (Salud, Bienestar y Envejecimiento [Health, Well-Being and Ageing]) Colombia Survey 2015, presented in October 2021 at the Universidad del Rosario.