Globicatella is a genus of catalase-negative, facultative anaerobes, and non-hemolytic Gram-positive cocci, arranged in pairs or in short chains. Twenty-five positive urine cultures, mainly obtained by catheterization, and two urinary stone cultures due to Globicatella spp. were retrospectively recorded from patients between January 1, 2014 and October 31, 2024. Isolates were identified by mass spectrometry (Vitek MS), 16S rRNA gene sequencing and biochemical tests. Most patients had complex uropathies or congenital malformations of the urinary tract. A high percentage of the isolates showed high ceftriaxone (CRO) MICs (MIC50 and MIC90: 2–16μg/ml) and almost half of them had low penicillin (PEN) MICs (MIC50 and MIC90: 0.25 and 2μg/ml). The present study is the most extensive report of Globicatella urinary tract infections in children.

Globicatella es un género de cocos gram positivos dispuestos en pares o en cadenas cortas, catalasa negativos, anaerobios facultativos y no hemolíticos. Se registraron retrospectivamente 25 urocultivos positivos, obtenidos principalmente por cateterismo, y dos cultivos de cálculos urinarios por Globicatella spp. de 26 pacientes entre el 1 de enero de 2014 y el 31 de octubre de 2024. Los aislamientos se identificaron mediante espectrometría de masas (Vitek MS), secuenciación del gen 16SARNr y pruebas bioquímicas. La mayoría de los pacientes presentaban uropatías complejas o malformaciones congénitas del tracto urinario. Un alto porcentaje de los aislamientos presentó CIM más elevadas para ceftriaxona (CRO) (CIM50 y CIM90: 2 y 16μg/ml) y casi la mitad de aquellos mostraron CIM bajas para penicilina (PEN) (CIM50 y CIM90: 0,25 y 2μg/ml). Esta es la serie más extensa de infecciones del tracto urinario debidas a Globicatella en niños.

Globicatella was described for the first time in 1992 as a new genus of catalase-negative, facultative anaerobes, and non-hemolytic gram-positive cocci, arranged in pairs or in short chains4. Two species belonging to this genus were described: Globicatella sanguinis (previously G. sanguis) and Globicatella sulfidifaciens16. The importance of the latter species in human pathology remains unclear, given that the identification methods currently used are not completely reliable for determining the species14. Globicatella spp. are unusual pathogens that, through the use of commercial phenotypic methods, could be identified or misdiagnosed as group viridans streptococci (GVS) due to their similarity in colonial morphology. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) is a reliable method for the identification of Globicatella spp. at the genus level, but not at the species level13.

Bacteria of this genus can colonize the inguinal skin and other mucosal surfaces. They have occasionally been found as causal agents of bacteremia12, osteomyelitis9, meningitis12, endocarditis13, and endophtalmitis2 in humans, and of animal infections8. However, the epidemiology and clinical significance of this pathogen remain largely unknown.

Globicatella spp. have seldom been isolated from urine samples12,13, but these were insufficiently studied cases of urinary tract infections (UTIs), mostly in elderly patients.

The precise identification of these microorganisms is important not only for epidemiological purposes, but also because of their pattern of low minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of penicillin (PEN) and high MIC of ceftriaxone (CRO), unusual for similar bacteria, such as most GVS and other related organisms12.

The aim of this study was to describe a series of cases of UTI due to Globicatella spp. in pediatric patients diagnosed in a high complexity pediatric hospital of the City of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

A retrospective and descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted between January 1, 2014 and October 31, 2024. Clinical records of patients with UTI due to Globicatella spp., either as unique isolate or as part of a mixed microbiota, were analyzed. A hospital computer system was used to obtain patients’clinical data. The following data were recorded: age, sex, symptoms and underlying diseases.

Catheterized urine samples were collected by specialized personnel or by patients or family members trained in the procedure. Clean-catch or midstream urine samples were obtained using standard methods.

Intraoperative urine samples and stones were collected in the operating room by the surgeons. Urinalysis involved microscopic observation of the sediment, estimation of the number of leukocytes and red blood cells per 400X field, determination of pH and other parameters that were not considered in this study.

Urine samples were cultured using the calibrated loop method on CHROMagar™ Orientation (CHROMagar, Paris, France) and chocolate agar. Plates were incubated in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 72h. A colony count >104CFU/ml was considered a positive result.

Stone culture was performed according to the classic method of Nemoy and Stamey10, i.e., the collected stones were washed four times with sterile physiological saline. Each washing solution was cultured using the calibrated loop method on CHROMagar™ Orientation and chocolate agar. After washing, the stones were crushed and suspended in the same volumen of sterile saline used in the previous washes, then shaken to obtain a homogeneous suspension. This solution was cultured immediately after crushing. Bacteria were considered to be within the stone if the colony count of the crushed stone was more than 1 log higher than that of the fourth wash.

Gram-positive organisms growing in chocolate agar were identified by mass spectroscopy and conventional tests. Identification by mass spectrometry was performed with the bioMérieux (MALDI-TOF MS Legacy, Marcy l’Etoile, France) spectrometer using the Acquisition Station software and VITEK® FLEXPREP™ software. A colony of each isolate was spotted onto an analytical slide and extracted with 0.5μl of 70% formic acid (spot technique) and, subsequently allowed to dry at room temperature. Samples were then covered with 1μl of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA) matrix until crystallized at room temperature. Mass spectra were analyzed within the range of 2000–20000 m/z. The isolates were identified using VITEK MS software version V3.0.

For result interpretation, cutoff points were applied according to the manufacturer's recommendations: a score of ≥60% (i.e., indicating a confidence level of 60% or more) is considered reliable, resulting in a “single-choice identification” at the genus level. A score of ≥60% is also indicative of a “good species identification.” Furthermore, internal studies of the system indicate that values of ≥95% represent high confidence at the species level. The VITEK system considers ≥60% a reliable level, given its population database and advanced algorithm.

Conventional biochemical tests were also used. The catalase test and hemolysis on sheep blood agar were the initial screening tests. For catalase-negative non-hemolytic gram-positive cocci, other biochemical tests, including bile esculin, NaCl 6.5%, H2S production in triple sugar iron (TSI), pyrronidonyl arilamidase (PYR) and leucine aminopeptidase (LAP), were used. PYR and LAP kits were provided by Laboratorios Britania (Buenos Aires, Argentina).

Molecular methodsThe near-full-length 16SrRNA gene was PCR-amplified and sequenced using specific primers 63f and 1387r, as previously described by Marchesi et al.7.

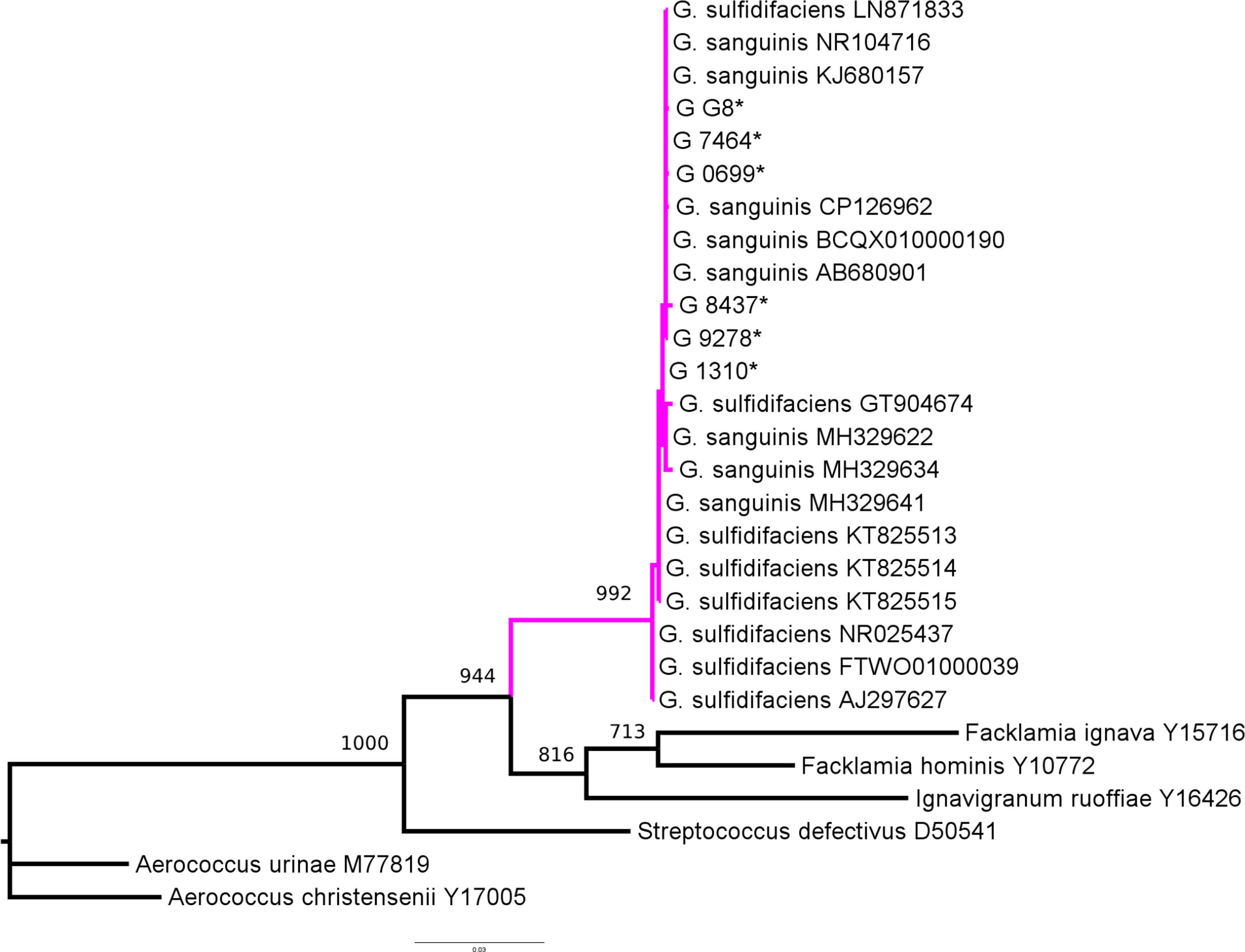

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the maximum likelihood method implemented in the PhyML web server5. Reference sequences were selected from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) and SILVA ribosomal RNA gene databases (https://www.arb-silva.de/)11.

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests to penicillin and ceftriaxone were performed for 19 and 17 isolates respectively, using Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) on Mueller Hinton agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood. The breakpoints for susceptibility and resistance to PEN and CRO used were those recommended by the CLSI for viridans group streptococci: S ≤0.125μg/ml; R ≥4μg/ml, and S ≤1μg/mL; R ≥4μg/ml, respectively3. Antimicrobial susceptibility to other antibiotics (trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, levofloxacin) was tested by the disk diffusion method only when clinically necessary. These results were not included in this study.

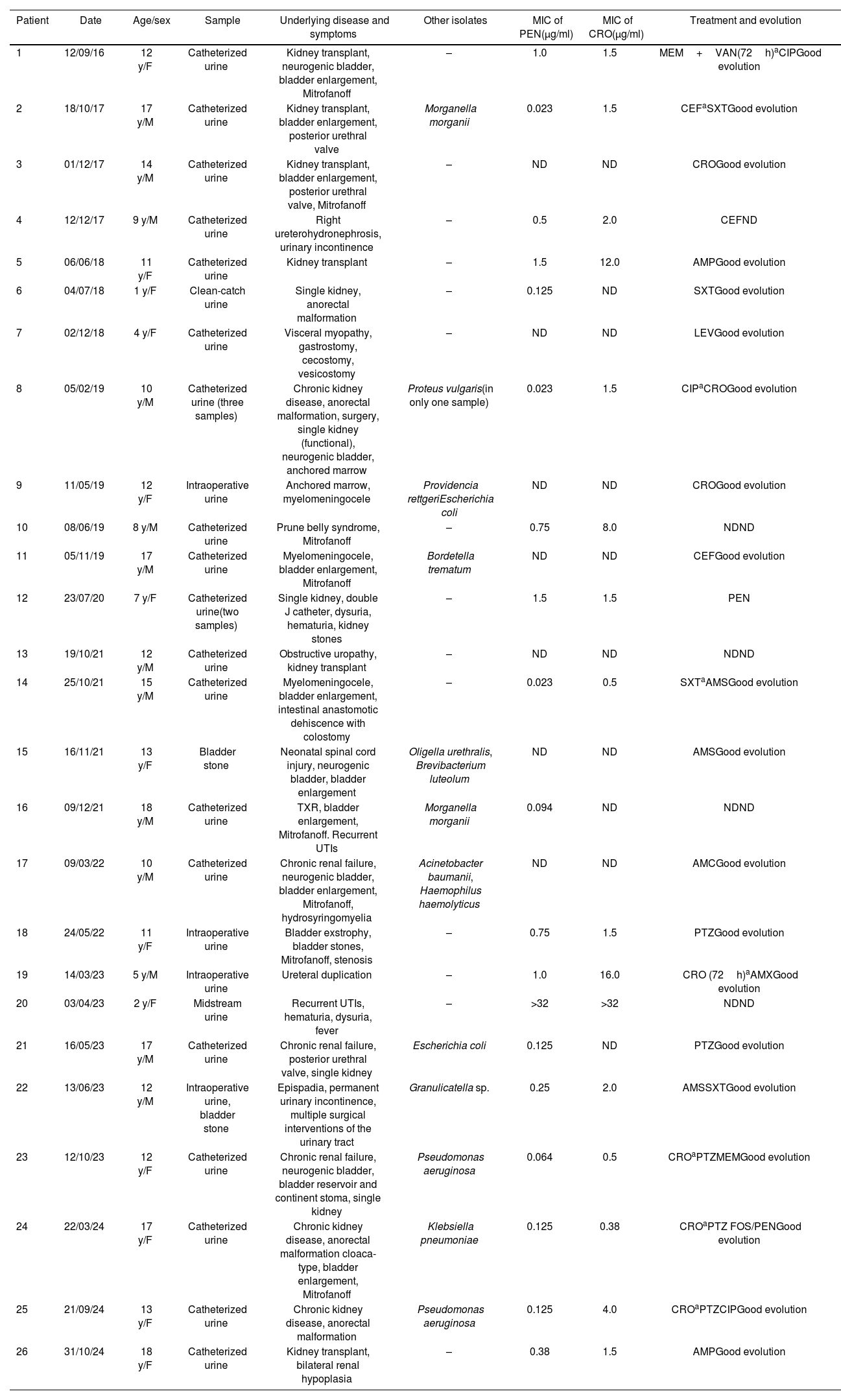

Twenty-four positive urine cultures (excluding repeated positive cultures), mainly obtained by catheterization (n=19), along with one intraoperative culture plus urinary stones, and an additional urinary stone culture from 26 patients were positive for Globicatella spp. The median age of the patients was 12 years (IQR: 1–18), with an equal distribution for males and females. All but one patient had severe underlying conditions, including myelomeningocele, ureterohydronephrosis, posterior urethral valve, urethral duplication, epispadias, renal hypoplasia, cystic kidney disease, bladder exstrophy, anorectal malformation, prune belly syndrome, or were kidney transplant recipients (Table 1).

Patients, samples, and susceptibility data of Globicatella isolates.

| Patient | Date | Age/sex | Sample | Underlying disease and symptoms | Other isolates | MIC of PEN(μg/ml) | MIC of CRO(μg/ml) | Treatment and evolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12/09/16 | 12 y/F | Catheterized urine | Kidney transplant, neurogenic bladder, bladder enlargement, Mitrofanoff | – | 1.0 | 1.5 | MEM+VAN(72h)aCIPGood evolution |

| 2 | 18/10/17 | 17 y/M | Catheterized urine | Kidney transplant, bladder enlargement, posterior urethral valve | Morganella morganii | 0.023 | 1.5 | CEFaSXTGood evolution |

| 3 | 01/12/17 | 14 y/M | Catheterized urine | Kidney transplant, bladder enlargement, posterior urethral valve, Mitrofanoff | – | ND | ND | CROGood evolution |

| 4 | 12/12/17 | 9 y/M | Catheterized urine | Right ureterohydronephrosis, urinary incontinence | – | 0.5 | 2.0 | CEFND |

| 5 | 06/06/18 | 11 y/F | Catheterized urine | Kidney transplant | – | 1.5 | 12.0 | AMPGood evolution |

| 6 | 04/07/18 | 1 y/F | Clean-catch urine | Single kidney, anorectal malformation | – | 0.125 | ND | SXTGood evolution |

| 7 | 02/12/18 | 4 y/F | Catheterized urine | Visceral myopathy, gastrostomy, cecostomy, vesicostomy | – | ND | ND | LEVGood evolution |

| 8 | 05/02/19 | 10 y/M | Catheterized urine (three samples) | Chronic kidney disease, anorectal malformation, surgery, single kidney (functional), neurogenic bladder, anchored marrow | Proteus vulgaris(in only one sample) | 0.023 | 1.5 | CIPaCROGood evolution |

| 9 | 11/05/19 | 12 y/F | Intraoperative urine | Anchored marrow, myelomeningocele | Providencia rettgeriEscherichia coli | ND | ND | CROGood evolution |

| 10 | 08/06/19 | 8 y/M | Catheterized urine | Prune belly syndrome, Mitrofanoff | – | 0.75 | 8.0 | NDND |

| 11 | 05/11/19 | 17 y/M | Catheterized urine | Myelomeningocele, bladder enlargement, Mitrofanoff | Bordetella trematum | ND | ND | CEFGood evolution |

| 12 | 23/07/20 | 7 y/F | Catheterized urine(two samples) | Single kidney, double J catheter, dysuria, hematuria, kidney stones | – | 1.5 | 1.5 | PEN |

| 13 | 19/10/21 | 12 y/M | Catheterized urine | Obstructive uropathy, kidney transplant | – | ND | ND | NDND |

| 14 | 25/10/21 | 15 y/M | Catheterized urine | Myelomeningocele, bladder enlargement, intestinal anastomotic dehiscence with colostomy | – | 0.023 | 0.5 | SXTaAMSGood evolution |

| 15 | 16/11/21 | 13 y/F | Bladder stone | Neonatal spinal cord injury, neurogenic bladder, bladder enlargement | Oligella urethralis, Brevibacterium luteolum | ND | ND | AMSGood evolution |

| 16 | 09/12/21 | 18 y/M | Catheterized urine | TXR, bladder enlargement, Mitrofanoff. Recurrent UTIs | Morganella morganii | 0.094 | ND | NDND |

| 17 | 09/03/22 | 10 y/M | Catheterized urine | Chronic renal failure, neurogenic bladder, bladder enlargement, Mitrofanoff, hydrosyringomyelia | Acinetobacter baumanii, Haemophilus haemolyticus | ND | ND | AMCGood evolution |

| 18 | 24/05/22 | 11 y/F | Intraoperative urine | Bladder exstrophy, bladder stones, Mitrofanoff, stenosis | – | 0.75 | 1.5 | PTZGood evolution |

| 19 | 14/03/23 | 5 y/M | Intraoperative urine | Ureteral duplication | – | 1.0 | 16.0 | CRO (72h)aAMXGood evolution |

| 20 | 03/04/23 | 2 y/F | Midstream urine | Recurrent UTIs, hematuria, dysuria, fever | – | >32 | >32 | NDND |

| 21 | 16/05/23 | 17 y/M | Catheterized urine | Chronic renal failure, posterior urethral valve, single kidney | Escherichia coli | 0.125 | ND | PTZGood evolution |

| 22 | 13/06/23 | 12 y/M | Intraoperative urine, bladder stone | Epispadia, permanent urinary incontinence, multiple surgical interventions of the urinary tract | Granulicatella sp. | 0.25 | 2.0 | AMSSXTGood evolution |

| 23 | 12/10/23 | 12 y/F | Catheterized urine | Chronic renal failure, neurogenic bladder, bladder reservoir and continent stoma, single kidney | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0.064 | 0.5 | CROaPTZMEMGood evolution |

| 24 | 22/03/24 | 17 y/F | Catheterized urine | Chronic kidney disease, anorectal malformation cloaca-type, bladder enlargement, Mitrofanoff | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0.125 | 0.38 | CROaPTZ FOS/PENGood evolution |

| 25 | 21/09/24 | 13 y/F | Catheterized urine | Chronic kidney disease, anorectal malformation | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0.125 | 4.0 | CROaPTZCIPGood evolution |

| 26 | 31/10/24 | 18 y/F | Catheterized urine | Kidney transplant, bilateral renal hypoplasia | – | 0.38 | 1.5 | AMPGood evolution |

MIC: minimal inhibitory concentration; y: years; F: female; M: male; ND: not determined; MEM: meropenem; VAN: vancomycin; CIP: ciprofloxacin; CEF: cephalexin; SXT: trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; CRO: ceftriaxone; AMP: ampicillin; LEV: levofloxacin; AMC: amoxicillin–clavulanic acid; PTZ: piperacillin–tazobactam; AMX: amoxicillin; AMS: ampicillin–sulbactam; FOS: fosfomycin; PEN: penicillin V.

Regarding the urinalysis, all samples (100%) had a pH between 6.6 and 7.4; 78% of the urinary pellets exhibited significant leukocyturia and/or hematuria (i.e., more than 5 leukocytes or red blood cells per 400X field) and 60% of the cultures were monomicrobial, with colony counts between 10000 and 100000CFU/ml on chocolate agar. Based on MALDI-TOF MS results and conventional biochemical tests (bile esculin and NaCl 6.5% positive; H2S production in TSI; PYR and LAP negative), the isolates were identified as Globicatella spp. Confidence values obtained by Vitek MS for each tested strain of 99.9% for G. sanguinis, except for two (50% G. sanguinis–50% G. sulfidifaciens), indicated a reliable identification, at least to the genus level.

For 19 isolates, the MIC50, MIC90 and range of PEN were 0.25, 2.0, and 0.03 to >32μg/ml, respectively, and those for CRO (for 16 isolates) were 2.0, 16.0, and 0.5 to >32μg/ml.

Twenty-two patients were treated on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the susceptibility of accompanying pathogens in mixed infections. Of the 21 patients whose evolution was known, all had good clinical outcomes (Table 1).

Only six isolates were available for 16SrRNA gene sequencing. The sequence analysis of the 16SrRNA gene revealed over 99.76% similarity among them. Two sequences, G_7464 and G_9278 of bacteria isolated in the years 2024 and 2023 respectively, were identical. These six sequences also shared more than 99% similarity to sequences of the genus Globicatella, particularly G. sanguinis. Sequences were submitted to GenBank under the following accesion numbers: G_7464 PV702875, G_9278 PV702876, G_1310 PV702877, G_8437 PV702878, G_G8 PV702879 and G_0699 PV702880.

Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that all six isolates belonged to the genus Globicatella (Fig. 1); however, species-level identification could not be determined, although the absence of H2S in TSI medium, a characteristic of G. sanguinis, was observed for these isolates.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree for the genus Globicatella. Magenta-colored branches indicate the clade corresponding to the genus Globicatella. Taxon names include both the bacterial species name and the accession number. Taxon names marked with an asterisk (*) indicate the six isolates analyzed in this study. Bootstrap values, calculated from 1000 pseudoreplicates, are shown above the tree branches.

Only a few well-documented cases of UTI involving Globicatella spp. were published, and all of them were from adult patients. In one case, a UTI complicated by endocarditis in an 87-year-old woman with severe underlying neurological condition13. G. sanguinis was isolated both from blood and urine and identified by Rapid ID32 Strep and 16SrRNA sequencing. Urosepsis due to G. sanguinis was also described in an 82-year-old female by Abdul-Redha et al. in Denmark1. In another UTI report, G. sanguinis was isolated from a polymicrobial urethral catheter biofilm, and in this case, proteins with potential roles in crosstalk with the host environment were studied15. Both studies involved adult patients.

At least to our knowledge, the present study is the most extensive study describing urinary tract infections of pediatric patients due to Globicatella spp. identified by mass spectrometry (Vitek MS), 16SrRNA gene sequencing and biochemical tests. Children with urinary infections due to Globicatella spp. had a median age of 12 years with a predominance of males and, notably, all of them but one had complex uropathies or congenital malformation of the urinary tract. Globicatella was not detected in previously healthy patients or in those with other pathologies. Most of urines were alkaline, and the majority exhibited pathological sediment. Cultures were mostly monomicrobial with high counts on chocolate agar (Table 1).

Previous studies have shown that the low divergence in 16SrRNA gene sequences between G. sanguinis and G. sulfidifaciens hinders species-level identification6,8,9. Our findings align with these observations, highlighting that, although 16S rRNA analysis is undoubtedly valuable for the preliminary identification of the genus Globicatella, it remains inadequate for the species-level classification.

As previously described in the literature, it was observed that a high percentage of the isolates showed high CRO MICs, while almost half showed low PEN MICs12,13. PEN MICs were currently lower than those of CRO. The clinical impact of these ceftriaxone MIC values on the treatment of UTIs remains unclear, as urinary concentrations of this antibiotic can greatly exceed its MIC value.

A limitation of this study is that only six isolates were available for sequencing, but all of them confirmed the previous results of identification by other methods.

At least to our knowledge this is the most extensive study of Globicatella spp. UTI in pediatric patients, identified by molecular methods, mass spectrometry and conventional tests. Although the available evidence suggests that these are isolates of G. sanguinis, including the absence of H2S production, we cannot rule out that some of them may belong to the species G. sulfidifaciens.

Almost all patients had complex uropathies or congenital urinary tract malformations. Accurate identification of Globicatella spp. is important, as these bacteria are frequently more susceptible to PEN than to CRO.

FundingCosts for this study have been covered by hospital funding. LAP and PYR kits have been provided by Laboratorios Britania.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

We specially acknowledge Andrea Mangano, PhD, and Diana Viale, MSc, for providing the opportunity to conduct this research at the Microbiology Department of the Hospital de Pediatría “Prof. Dr. Juan P. Garrahan”. We also acknowledge all involved healthcare personnel and laboratory staff of the hospital.