Rift Valley fever is a mosquito-borne disease caused by the Rift Valley Fever Virus (RVFV) belonging to the genus Phlebovirus. This virus causes febrile or hemorrhagic illness in humans and ruminants, such as abortion, and death; especially in young sheep, cattle, and goats resulting in devastating epidemics in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. The WHO has included this virus in Bluepoint's list of eight pathogens. This virus is a crucial health concern in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), as the Kingdom is regularly exposed to this virus from the original source of East African countries. A complete understanding of viral pathogenesis, epidemiology, antiviral therapeutics, and human vaccines is still lacking. This review aims to provide an update on the status, pathogenesis, prevalence, challenges, and future prospects of RVFV in the KSA. The information provided will aid in the design and development of disease management strategies and novel prophylactic and therapeutic measures to control the infection and disease progression of RVFV in both humans and animals.

La fiebre del Valle del Rift es una enfermedad transmitida por mosquitos, y causada por el virus de la fiebre del Valle del Rift (RVFV, por sus siglas en inglés), perteneciente al género Phlebovirus. Este virus causa enfermedades febriles o hemorrágicas en humanos y rumiantes, como abortos, y puede ocasionar la muerte. Especialmente en ovejas jóvenes, ganado vacuno y cabras, el RVFV ha provocado epidemias devastadoras en África y la Península Arábiga. La OMS ha incluido este virus en la lista de los ocho patógenos de Bluepoint. En el Reino de Arabia Saudita, el RVFV es un problema sanitario crucial debido a su regular ingreso desde su fuente original: los países del este de África. Todavía falta una comprensión completa de muchos aspectos de esta afección, incluidas la patogénesis viral, la epidemiología, las terapias antivirales y las vacunas humanas. Esta revisión busca ser una actualización sobre el estatus, la patogénesis y la prevalencia del RVFV en Arabia Saudita, y dar cuenta de los desafíos y las perspectivas futuras. La información proporcionada ayudará en el diseño y desarrollo de estrategias de manejo de enfermedades, y de nuevas medidas profilácticas y terapéuticas para controlar la infección y la progresión de la enfermedad causada por el RVFV tanto en humanos como en animales.

Rift Valley Fever Virus is an ss-RNA virus that causes a zoonotic illness known as Rift Valley fever (RVF) disease transmitted by mosquitoes. This virus is responsible for periodic outbreaks and poses a serious threat to human and veterinary health, finally resulting in social and economic loss1–4. RVFV is a neglected virus, and very little is known about it. The virus is geographically distributed in 37 countries across the Middle East and Africa. RVFV was isolated for the first time from a sheep in Kenya during the outbreak in 19305. The first outbreak of RVFV in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) was reported in 2000 from a fatal case of RVF in adults. Since then, sporadic RVFV cases have been reported from the Kingdom6. Since 2000, the WHO has reported various outbreaks from different geographical regions that include, Egypt (2003), Kenya, Somalia and Tanzania (2006), Sudan (2007), Madagascar (2008, 2009), Republic of South Africa (2010), Republic of Mauritania (2012), and Republic of Niger (2016). Based on the current Bluepoint list and the risks posed by Disease X and RVFV developed by the WHO, RVFV has been included along with emerging viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHV), Ebola virus, Nipah virus, Zika virus, Lassa fever virus, all of which are in the priority list for research and development2,7,8. RVFV comprises the ss-RNA genome with three main segments designated as small (S), medium (M), and large (L). The mosquito vectors of RVFV fall under 73 species and eight genera of the family Culicidae2,9. Due to the RVFV infection, the rate of mortality varies from 70 to 100% in lamb and kids, and 20 to 70% in sheep and calves. Lower susceptibility has been observed in cattle and camels, but the rate of abortion may reach up to 85–100%2,10. Non-vector transmission can occur in humans through direct interaction with contaminated animals, such as improper handling during processing, milking, breeding, and birthing, and by consuming raw animal products from infected livestock11. Based on the CDC and the WHO, approximately 8–10% of RVFV-infected humans develop mild to severe symptoms, such as flu-like illness, muscle pain, joint pain and headache, neck stiffness, sensitivity to light, loss of appetite and vomiting, blurred and decreased vision, encephalitis and bleeding in less than 1% and a severe case of hemorrhagic fever with 1% fatality rate. The incubation period ranges from 2 to 5 days after exposure to RVFV12,13. RVFV transmission can lead to outbreaks of illness in livestock, which can result in significant economic impacts on the affected communities. In humans, RVFV symptoms range from mild flu-like symptoms to severe hemorrhagic fever, while RVF outbreaks in livestock can have significant economic impacts on the affected communities. Based on the current status of published reports, the main objective of this review is to discuss the pathogenesis, epidemiology, challenges, and future prospects related to diagnosis, vaccination, vector control, disease progression and management strategies, as well as the research progress made so far regarding RVFV in the KSA.

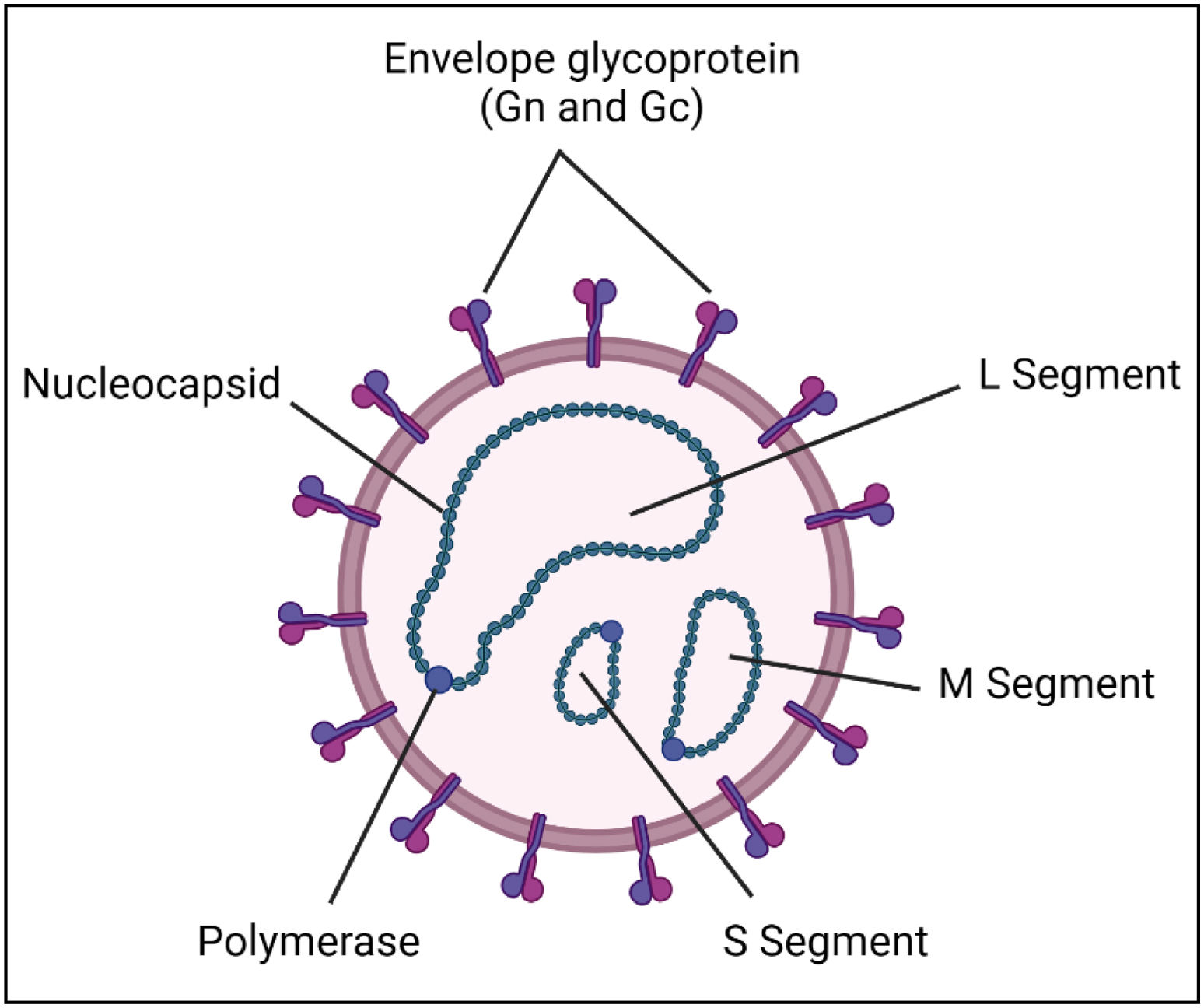

Pathogenesis of RVFVStructure of the etiological agent (RVFV)RVFV has a segmented negative-stranded genome. RVFV is an enveloped spherical or pleomorphic virus containing a segmented single-stranded RNA and a range between 90 and 110nm in size. Its genome is about 12kb long, and has large (L), medium (M), and small (S) segments that create circular ribonucleoprotein complexes14. Thus, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses reclassified it in 2017, moving it from the defunct Bunyaviridae to the Phenuiviridae family (genus Phlebovirus) in the order Bunyavirales15. This classification includes a large and diverse group of RNA viruses such as the Hantaviridae and Nairoviridae families, often transmitted by arthropods (e.g., ticks) and mosquitoes and responsible for a range of diseases in humans and animals (e.g., Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, hantavirus) (Fig. 1).

RVFV attachment and host cell entryRVFV can infect and replicate in the cytoplasm of diverse cell types, including mosquito cells, human and animal liver, blood, brain, lung, and kidney cells, and immune cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages16,17. However, it is unclear how it uses protein receptors on the host cell surface to enter these cells. If RVFV can infect various cell types, it may have multiple receptors that facilitate viral entry. Some studies suggest that C-type lectin molecule receptors on the human cell surface, such as dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin and other members of the C-type lectin family (e.g., L-SIGN) may play a role in RVFV attachment and entry16. Heparan sulfates such as phosphatidylserine are also possible factors in viral internalization18.

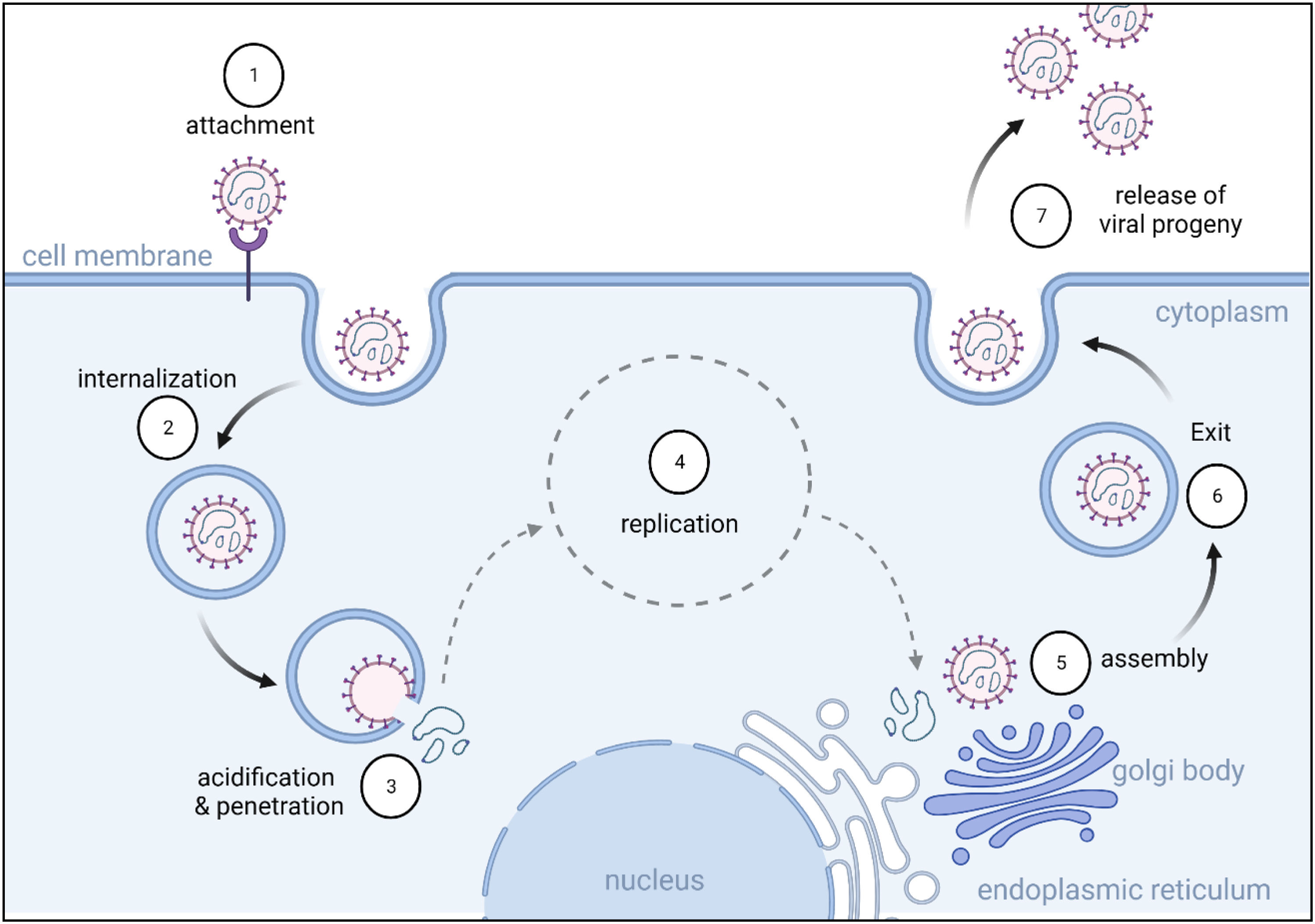

RVFV uncoating and replicationRVFV requires both Gc and Gn envelope glycoproteins to bind to the host cell surface and promote caveola-mediated endocytosis, where the virus is engulfed and transported into the cytoplasm inside an endosome19, as shown in Figure 2. Once inside the endosome, the acidic environment triggers virus uncoating by inducing a conformational change in the viral envelope proteins, allowing them to fuse with the endosomal membrane and release RNA into the cytoplasm. The viral RNA is then translated by the host cell's ribosomes to produce viral proteins (e.g., RdRp) for replication and assembly20. The translated RdRp replicates viral RNA by using it as a template to synthesize complementary negative-sense RNA molecules, which serve as templates to produce new positive-sense RNA molecules. RdRp then uses the positive-sense RNA molecules as templates to produce more negative-sense RNA molecules, making multiple copies of the virus that can be used to produce more viral proteins14. Replication of the RVFV genome causes modifications to the cellular membrane, creating a favorable environment for viral replication and construction that harms the infected cells, leading to tissue damage and inflammation21.

Illustration of Rift Valley Fever Virus cell cycle and replication: (1) attachment of viral particles to different receptors on the cell surface; (2) viral entry via endocytic machinery; (3) release of viral RNA from late endosomal compartments into the cytosol; (4) replication and transcription of the virus followed by protein synthesis; (5) assembly of viral progenies in the Golgi apparatus; (6) newly formed particles reach the cell surface inside the intracellular vesicles; (7) vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane and release the virus outside the cell.

With the aid of Gc and Gn, the replicated viral RNA and newly produced viral proteins assemble to form new virus particles, then fuse with the Golgi apparatus in the cytoplasm of the cell22. This process releases new virus particles from the infected cell by budding from the plasma membrane, where the virus acquires a lipid envelope from the host cell membrane as it exits. The released virus particles then infect new cells and continue the replication cycle23.

Hosts and vectors of RVFVA wide range of domestic ruminants, various wildlife, humans, and camel species are known to be susceptible to RVFV infection. These animals play a crucial role in maintaining the virus within the environment. In the KSA, the 2000–2011 epidemics in various regions incriminated livestock, particularly sheep and goats, as virus hosts. Wild animal species were also found to play a role in the epidemic. Furthermore, livestock trade plays an important role in the national economy of Saudi Arabia. Based on the published information, the virus circulates in their mosquito and vertebrate vectors for their survival and maintenance. Currently, RVFV has been isolated from multiple mosquito species and have been divided into two major groups as primary and secondary vectors24. The suspected primary vectors such as floodwater-breeding Aedes spp. are responsible for the potential transmission of the virus by both transovarial and horizontal means. Species of Culex, Anopheles, and Mansonia have been identified as secondary vectors for horizontal transmission during the high vector concentration and favorable conditions17. Additionally, RVFV is known to be transmitted mechanically by arthropods such as Culicoides, sand flies, and Stomoxys calcitrans24.

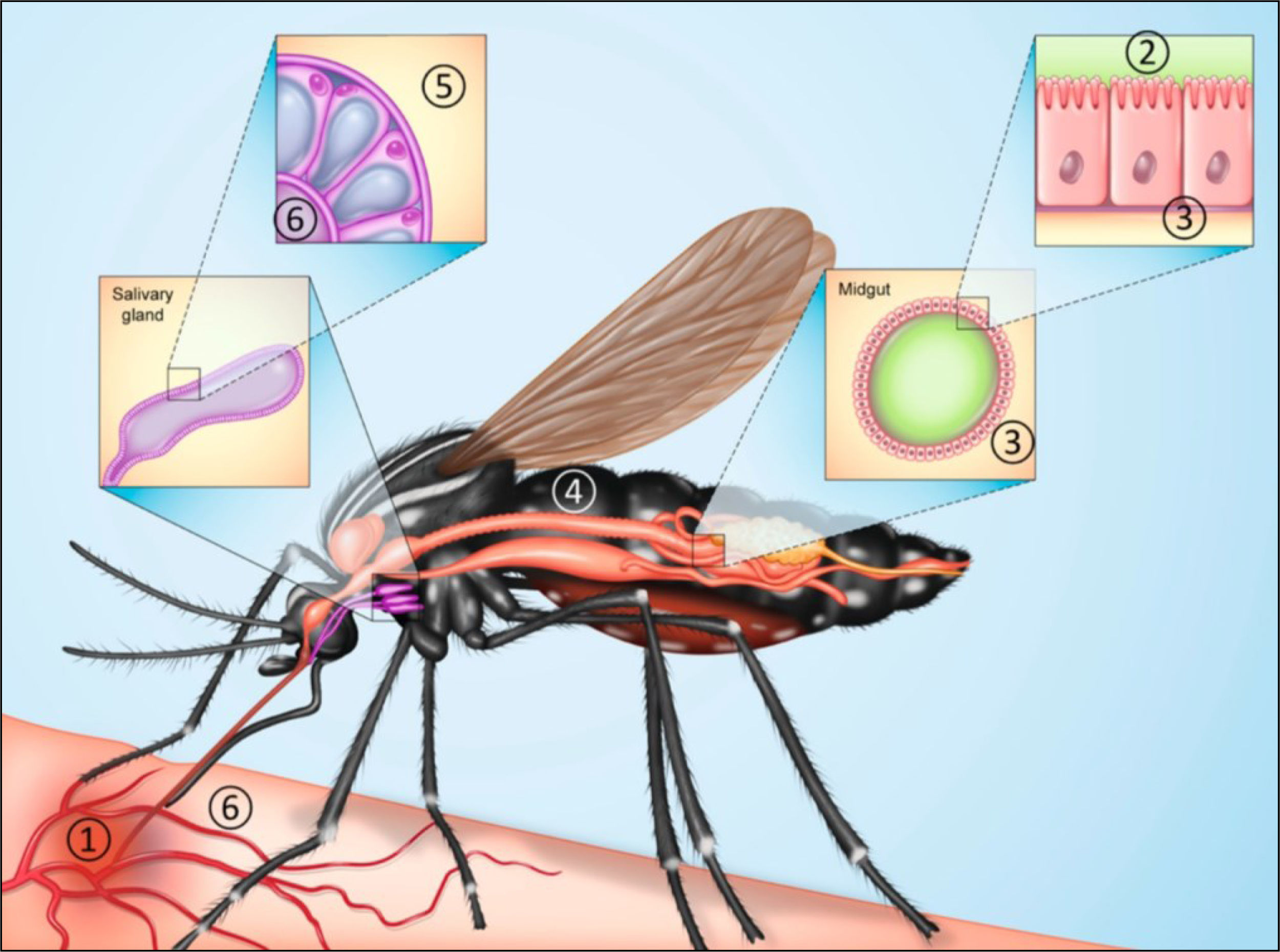

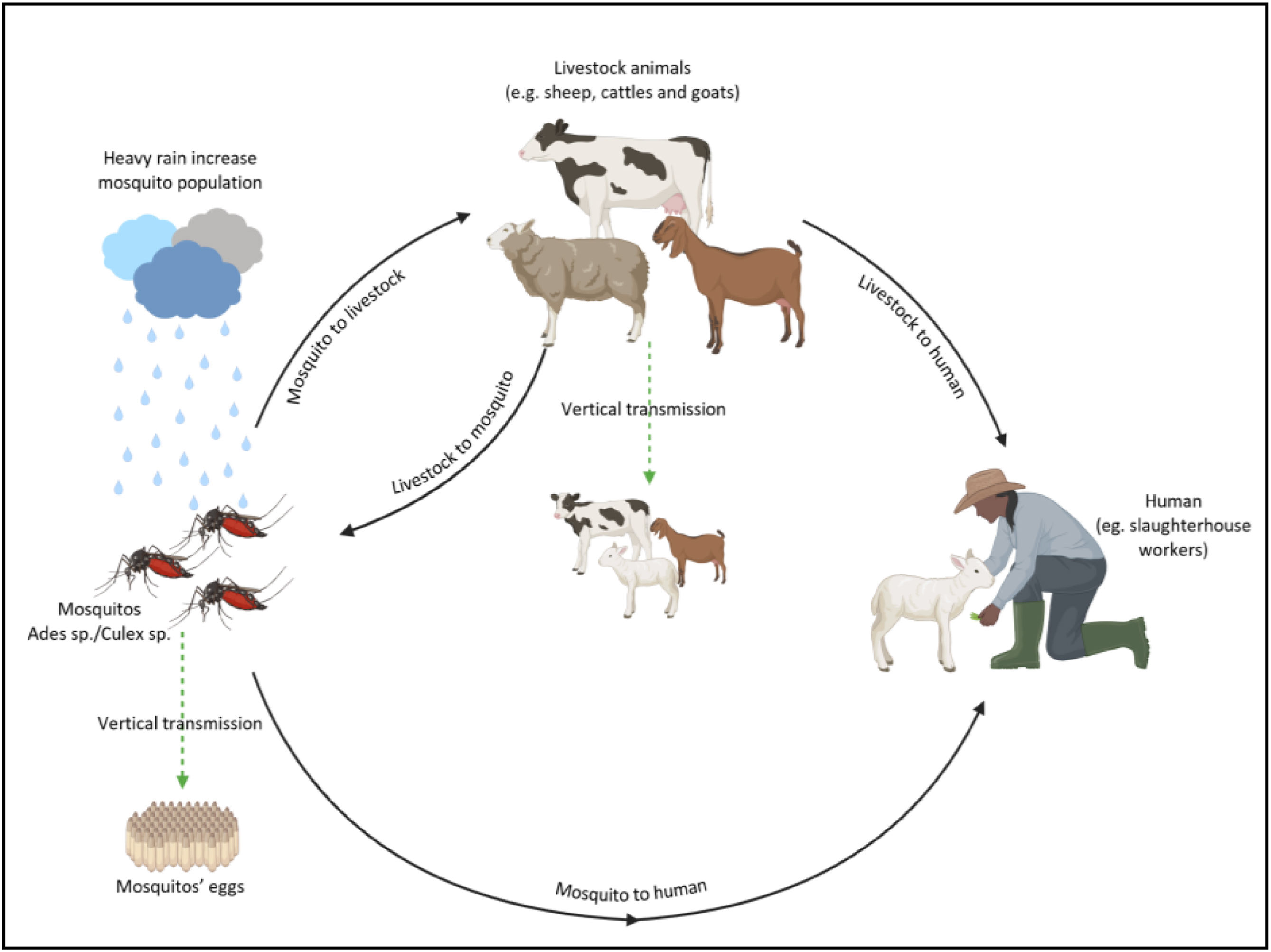

Mosquito vectors for RVFA wide range of mosquito species are known to transmit RVFV, including Aedes, Anopheles, Mansonia, Culex, Aedeomyia, and Coquillettidia17. Aedes spp. and Culex spp. are considered the primary transmission vectors in Africa, and Culex sp. are the primary transmission vectors in the Arabian Peninsula, Madagascar3,25. Adult female mosquitoes become infected with RVFV by biting and feeding on the blood of infected animals during the viremia stage. The virus can also be vertically transmitted to mosquito eggs in some species, such as Ae. macintoshi, Ae. ochraceus, Ae. sudanensis, and Ae. dentatus26 as well as Culex tarsalis27. Analyses of tissue tropism of the virus in adult offspring of these species indicate the presence of viral RNA in several organs, including the salivary glands, midgut, ovaries, testes, and head (Fig. 3)17,24. In drought-resistant mosquito eggs, the virus can remain dormant in between outbreaks and then release infected mosquitoes when they eventually hatch (Fig. 4)28,29.

Transmission of Rift Valley Fever Virus by female mosquitos. (1) Female mosquito feeds on the host during viremia. (2 and 3) Virus infects epithelial cells of midgut and begins to replicate, then migrates to other tissues. (4) Virus infects and replicates nerves, muscle, and fat cells (5 and 6). Virus reaches salivary glands, where it replicates and is transmitted from the saliva to new hosts via direct or indirect exposure28.

Transmission cycle of Rift Valley Fever Virus: from bites of infected mosquitoes, particularly Culex species, to humans and animals and vertically to mosquito offspring, which can repopulate during heavy rain seasons. The virus can also be transmitted through contact with contaminated blood, tissues, or bodily fluids of infected animals. Vertical transmission can occur in humans and livestock animals, as well.

Domestic livestock that transmit RVFV include cattle, sheep, goats, and camels1,2,9. These animals may contract the virus either by mosquito bites or direct or indirect exposure to contaminated body fluids and tissues, such as blood, milk, urine, placenta, and miscarried fetuses. Animals may pass the virus vertically to their offspring during pregnancy or suckling30. Infected animals usually develop high viremia. After 2–4 days of incubation, they start showing symptoms such as fever, hepatitis, and distinctly increased abortions and birth defects, a significant diagnostic feature observed by farmers. Evidence suggests that RVFV may also lower milk production in nursing animals due to the high metabolic reactions of infected cells31. RVFV-infected sheep also develop lesions, which have been discussed in detail in many published reports. Typically, young animals fare worse; for instance, compared to adult sheep, lambs infected with RVFV experience higher rates of severe hepatitis and death10. Recently, several studies have shown that RVFV can be transmitted to North African livestock and wildlife cell lines although the tested animals that carry the virus have remained asymptomatic50. RVFV infections in mammals are poorly known; however, based on a recent study, the presence of antibodies in nyalas (34%) and impalas (46%) indicates their possible role as virus reservoirs during inter-epidemic periods32.

RVF in humansIn humans, RVFV can be transmitted through mosquito bites, direct or indirect contact with infected animals or their tissues (e.g., handling infected animals or exposure to contaminated surfaces and equipment), and through vertical transmission from mother to fetus and women are at risk of late-term miscarriages. Thus far, no other routes of human-to-human transmission have been reported33. Generally, most human infections are asymptomatic and self-limiting, characterized by mild flu-like symptoms such as fever, weakness, back pain, and dizziness, which take a few days to resolve. In 8–10% of human RVFV infections, severe illness can occur, such as ocular disease in 0.5–2% of cases, as well as encephalitis and hemorrhagic fever in less than 1% of cases. Unfortunately, around 1% of patients who develop hemorrhagic symptoms die12,34. In humans, 1–3% of patients with RVFV infection develop severe diseases, for example, hemorrhagic fever, encephalitis, or blindness. Outbreaks among humans or animals occurred at rates of 5.8/year and 12.4/year, respectively. In a study conducted involving 664 humans, 361 cattle, 394 goats, and 242 sheep, the results showed that RVFV IgG seroprevalence in humans and animals was 2.1% and 9.5% respectively35. Recently, a study was conducted to prevent the vertical transmission of RVFV by a recombinant-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody. It was observed that mAb RVFV-268 immediately travels to the placental and fetal tissue just after the intraperitoneal injection and prevents the maternal and fetal RVFV infection in a dose-dependent way when given before the virus challenge. The mAb RVFV-268 shows efficacy in reducing virus replication and vertical transmission in a rat model. This monoclonal antibody has great potential for protecting the mother and offspring from vertical transmission of RVFV36.

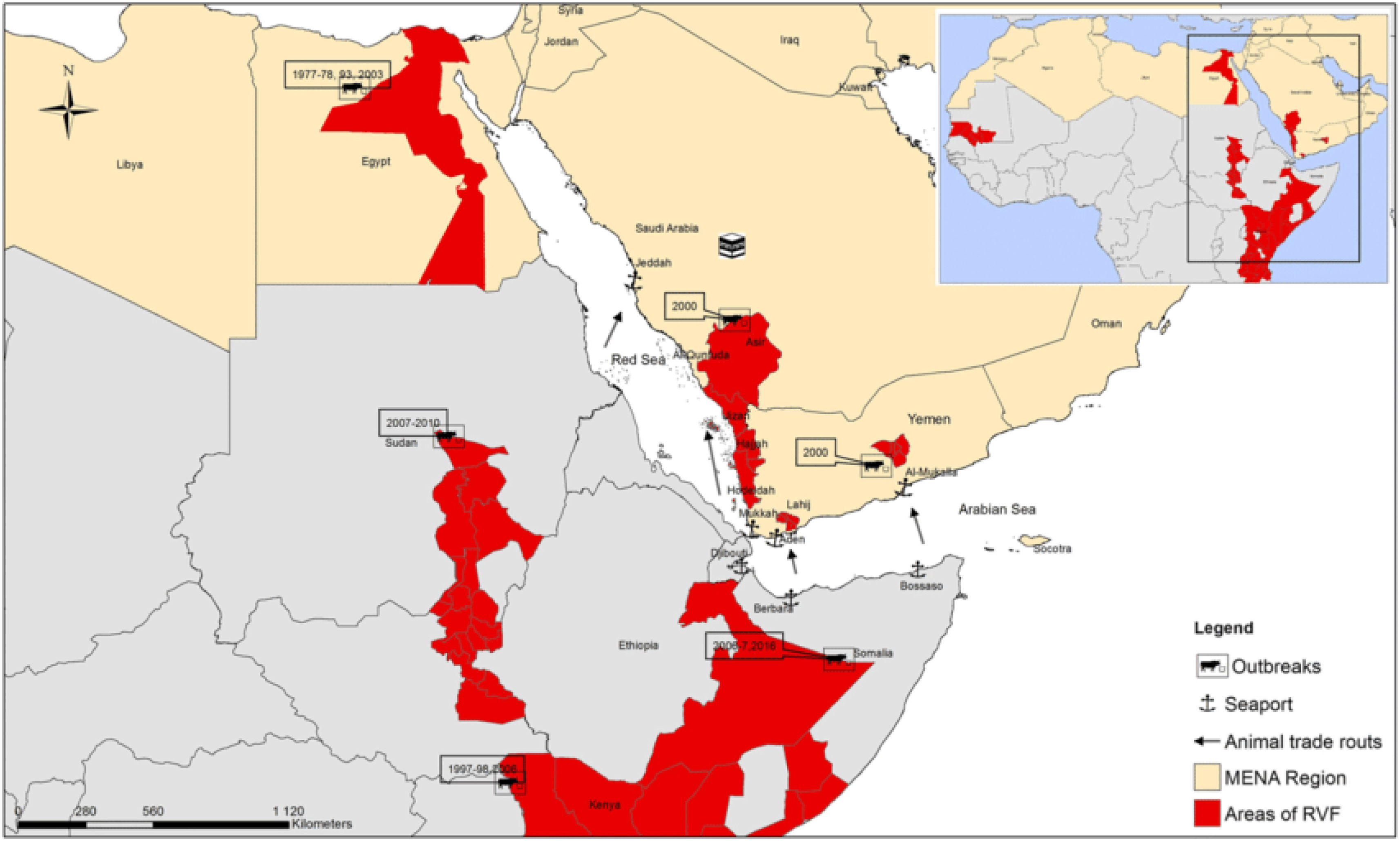

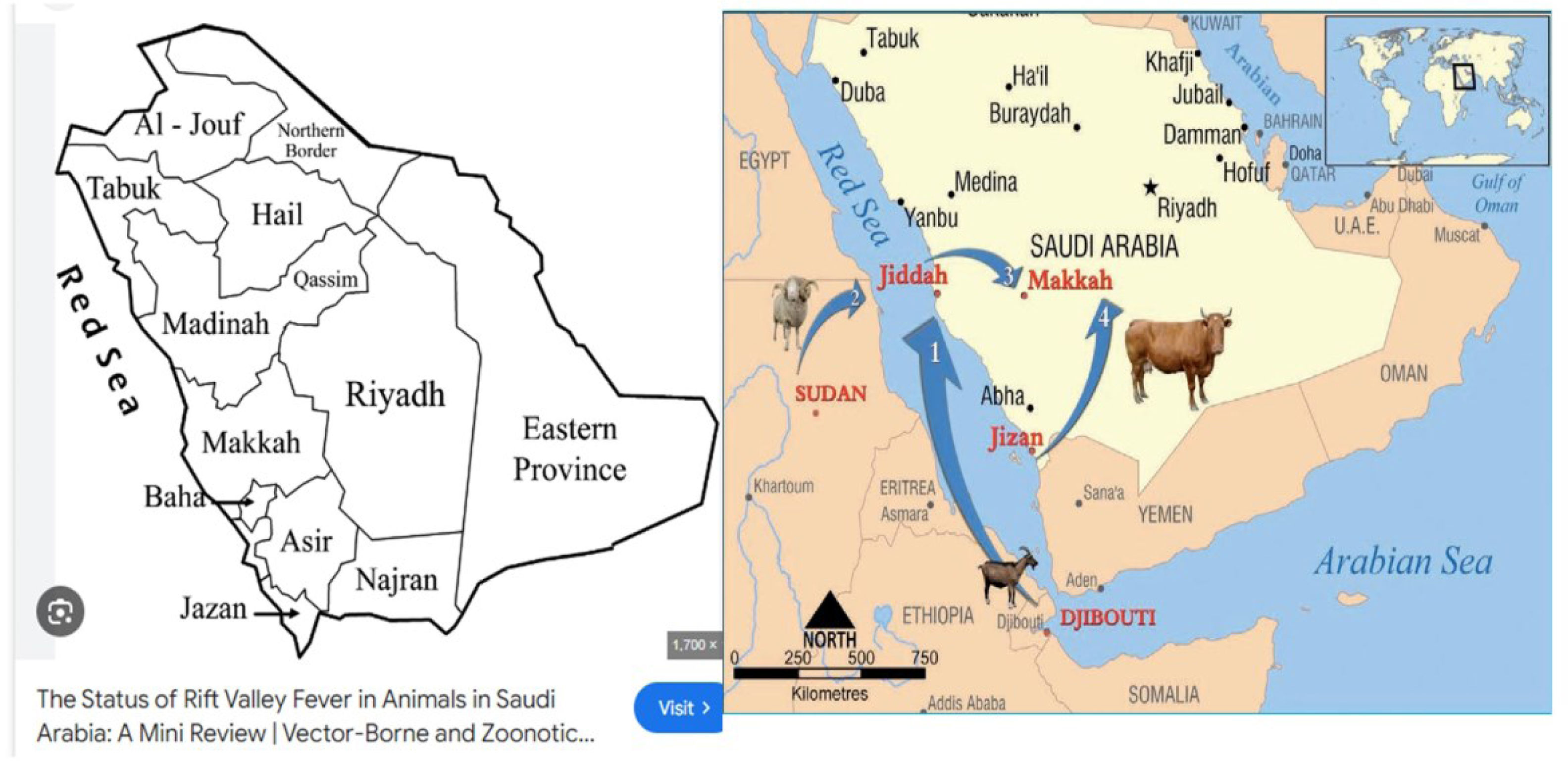

Epidemiology, incidence, and ecological dynamics of RVFV in the KSARVFV is considered a serious, social and economic threat to the KSA. When dealing with RVFV epidemiology, it is crucial to remember that there are essentially no geographic regions that are risk-free during the active transmission period. The first case of RVFV was identified in sheep in Kenya in 1930, and, since then, the virus has been reported in various geographical regions5. The worst documented outbreak was in August–September 2000, with an estimated death of 40000 animals and 883 human cases, resulting in 124 fatalities in the KSA while 1328 human cases, with 166 deaths were reported in Yemen. Most human cases were reported in the Najran region and its surroundings along the borderline with Yemen6,37,38. Since then, Saudi Arabian authorities have implemented several preventive programs to limit its recurrence. These efforts include livestock vaccination, mosquito surveillance, insecticide spray treatment, and biological control39. Over the past 25 years, this virus has expanded from eastern and southern Africa to the Middle East. Serological evidence that was obtained from Yemen and also from Turkey suggests its spread to a wider geographical area1,9 (Figs. 5 and 6).

Distribution of Rift Valley Fever Virus in some countries of the Middle East and North Africa region: the red color shows areas of RVFV outbreaks and/or epizootics and their dates37.

Analysis of the geographical spread of RVF cases in KSA has demonstrated that most outbreaks have been reported from the western, southwestern, and southern regions of the country. Currently, many studies have been conducted and various reports have been published on RVFV epidemiology, vectors, hosts, reservoirs, and environmental links related to epizootics and epidemics. Climatic conditions and stagnant water also play a significant role in vector populations and epidemics. The outbreak-free years (2010–2017) were not human or animal case-free. Regionally, RVFV cases have been reported mostly in the southwestern region of Saudi Arabia. Seasons with relatively fewer human RVFV cases have occurred from 2001 to 201830. The RVFV transmission cycle comprises a series of interactions between the virus, vectors, and susceptible mammalian hosts in favorable environments. The main route of RVFV transmission is through mosquito bites, though other modes of transmission can also occur. The Kingdom may be exploited as a gateway for the widespread transmission of RVFV in the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Due to global climate changes, favorable conditions have emerged for more extended vector breeding and seasonal expansions of vector insects and vertebrate hosts. The livestock trade and international travel, human movement, and multiple environmental, anthropogenic, ecological, and virus evolution are aligning for facilitating the invasion and establishment of RVFV in new regions and previously unreported territories40. The frequency of extreme weather conditions provides an opportunity to virus spread through infected humans, livestock, or vectors and exacerbate outbreak size and number per year41.

Consequently, it is essential to gain precise insight into RVFV for socio-economic growth and the well-being of public health and welfare in the animal industry40. Systematic data in the KSA is minimal and mostly confined to RVFV antibody prevalence to improve knowledge. Rift Valley fever not only has an impact on public health but is also a dangerous occupational disease for veterinarians, farmers, and slaughterhouse employees. There is an increased risk of human RVFV in the KSA, and various factors influence it, namely, zoonotic bridging mechanisms, water and irrigation systems, the Al-Harrah region ecology, and climatic factors, such as rainfall. Measures must be implemented to minimize the potential risk of human RVFV in the area. However, eradication has not been confirmed through methods such as routine screening of high-risk populations, such as slaughterhouse workers in the KSA. Moreover, satellite mapping from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) indicates a potential re-emergence of RVFV in several regions, including the Middle East, based on analyses of vegetated landscapes42.

Given the significant public health and economic impacts of RVFV, it is crucial to understand the pathogenesis, epidemiology, host–virus interactions, and status of the disease and virus spread, so that effective prevention and control measures can be designed, developed, and implemented41. Current measures largely rely on controlling mosquito populations and avoiding contact with infected animals. Although animal vaccines are administered in endemic regions, no human vaccine or antiviral therapy is yet available, and treatment is limited to supportive medication in mild cases43. Continuous animal, human, and vector surveillance is necessary, not only during the epidemic season but also during other seasons. The misdiagnosis of RVFV in humans and livestock is frequently reported in endemic regions44. These limitations highlight the pressing need for regular monitoring of both animals and humans, specifically slaughterhouse workers and those in the 2000 outbreak zone, and other susceptible regions of Saudi Arabia. Currently, the only approved serological diagnostic tools are limited to use in endemic countries and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reference laboratories: no commercial kits have been approved for detecting RVF in non-endemic countries45.

Significance of studying Rift Valley fever in the KSARVFV is re-emerging as one of the most important public health concerns in the KSA. In the 2000 outbreak, for the first time, RVFV was isolated and reported from a fatal case of RVF in adults in the KSA. Since then, sporadic RVFV cases continued to be reported from the KSA6. KSA is located in the Arabian Peninsula and is bordered by Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Yemen. A major portion of the country, including the Al-Harrah Desert and the Al-Nefud Desert, is characterized by desert rodents, one of the copious sources sustaining RVF outbreaks. It is a largely deserted country with remarkable ecological diversity ranging from the northern highlands of Asir to the Tihamah, an arid and hot coastal plain located to the west of the mountains, which are also home to wadis and oases. However, the climate is also highly irrigated and tropical, leading to the presence of seasonal and yearly rainfall on the oases. A unique feature that makes the KSA special and very sensitive for targeting RVFV is that the KSA has high animal holdings, and agriculture is one of the major contributors to the country's GDP. Any potential outbreaks can spread very quickly, leading to devastating socio-economic impacts on this sector, particularly for the people who rely on livestock reproduction. Based on the various studies conducted in different countries, it is reported that healthy individuals carry RVFV as asymptomatic carriers and the virus may persist for a longer time, especially in those areas where high mosquito multiplication is favored by environmental conditions29.

Environmental surveillance for RVFV disease prediction may be conducted by monitoring vegetation patterns through satellite remote sensing technologies, along with tracking the establishment of mosquito vectors by following significant rainfall, flooding, and water stagnation, which can result in epizootics and epidemics. An outbreak of RVFV in the Arabian Peninsula (Asir regions of Saudi Arabia) is likely if there is no vaccination and if no mosquito control is undertaken. The introduction of the virus can occur in the Arabian Peninsula by the importation of infected animals from continental Africa. It is important to study the outbreaks of RVFV in the KSA and to develop strategies for the prevention and treatment of animals for the country to be disease-free and to develop scientific research to make the necessary information available. A structured and effective surveillance of mosquito and arthropod vectors is urgently required for data accumulation on vector populations, environmental season variations, spatial extents, and disease spread in a particular area41. Economic losses are decreasing, and preventing the entry of RVFV to countries where outbreaks are not yet present is most obviously required. The importance of RVFV disease in terms of public and animal health and the availability of relevant information may also need the implementation of monitoring and vigilance plans. The early determination of the RVFV situation in the KSA will become a reference, as well as a measure of proactive methods.

Recently, a review study was conducted on sixteen years of the RVFV control program in the KSA. The control program included multiple strategies such as vector control, fog and sprinkle sprayers, draining and filling of water swamps with sufficient soil, surveillance of mosquitoes, biological control, sustaining animal vaccination, regular examination of herds, and serosurveillance during rainy season near the Yemen border and Jizan regions. This program effectively controlled RVFV prevalence by reducing it from 12.3% in 2000 to 0.015% in 2015. The RVF control program that was set up in the KSA has completely reversed the risk of re-occurrence of RVFV over the past 18 years and provided long-term protection against RVFV exposure. The effectiveness of the current control program can be demonstrated by the reduction in the prevalence of RVFV-specific immunoglobulin M antibodies, which declined from 12.3% in 2000 to 0.10% in 2017. Mosquito infection rates with RVFV have also declined, from 0.045 per 1000 for the genus Culex in 2014 to zero from 2015 to 201830. A reanalysis study was conducted recently in the southwestern region of the Arabian Peninsula regarding the 2000 RFVF outbreak in Southwestern Arabia. Based on satellite data and 2m×2m digital elevation images, it was observed that the potential areas of inundation or water impoundment existed until 2016–2018, contributing to the emergence of new outbreaks. However, due to effective control measures, no further RVFV presence was reported. The absence of RVFV in Southwestern Arabia indicates that the virus has not been established in mosquito vectors46.

ChallengesAlthough significant progress has been made in understanding the pathogenesis mechanism and epidemiological aspects of RVFV, many unanswered questions still remain for future studies. The most important challenge of RVFV is obtaining updated data on RVFV-positive samples based on passive surveillance reports. A major challenge in RVFV research in the KSA is the absence of an authentic national comprehensive RVFV-related database, which constrains an understanding of historical patterns of infection. So far, the true evolutionary patterns and long-term ecological behavior of the RVFV in the KSA are unknown. Many important questions remain unanswered regarding RVFV genetic diversity, host-switching, mechanisms of epizootic and epidemic initiation, time and place, and the nature of the enzootic maintenance cycle of the virus. Although domestic animals are considered important for the transmission and maintenance of RVFV in the local ecosystem, the actual role of wildlife in epizootics remains unknown. The continuous RVFV introduction into new endemic regions may pose a serious threat to humans, animals, and agricultural and economic sectors47. The role of camels, cattle, and other potential animal hosts in the maintenance and transmission of the virus is yet to be ascertained. Understanding such fundamental factors will assist in developing socio-ecological modeling that explores RVFV transmission dynamics and ecological relationships between vectors and hosts. Effective vector control measures and transmission models should be followed to control vector-borne diseases41. Such transmission models are crucial for delineating risk areas and predicting infection dynamics at a large scale48,49.

Additionally, while there is a need to determine seroprevalence against RVFV and the risk factors associated with seropositivity, few such local seroprevalence data are available, and they typically represent only small geographic areas. Detailed and integrated research work data on the RVFV event pattern is still lacking in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The scarcity of research on this field in animal and human populations may significantly hinder progress in research, management, and control. Despite the advancements made in disease diagnosis, in-house kits are lacking in resource-limited laboratories. An interdisciplinary approach is crucial for epidemiological scientists to refine research and develop scientific strategies to address Rift Valley fever zoonoses and pathogens to understand their presence and spread. Poor knowledge of RVF and infrequent media campaigns means that residents, animal keepers, and abattoir workers are unlikely to request laboratory tests in the event of an unusual human or sudden animal health issue. Chronic deficiencies in funding research on zoonotic diseases, limited laboratory infrastructure for confirmation, and a multifaceted, multistakeholder environment of animal husbandry have collectively contributed to the reduced number of published RVFV studies and curtailed the expansion of knowledge about the disease. Even when researchers have taken an interest in communicating scientific findings in the highest-ranking journals, attempts to establish contact with the relevant authorities have proved unsuccessful.

Future prospectsFuture studies should capitalize on understanding the RVFV infection cycle, which could potentially be beneficial in reducing the propensity for the spread of vectors to humans and livestock. In addition, there is a direct need to establish a collaborative relationship with internationally recognized research institutes to build the capacity and infrastructure required to establish research activities that address the prospects in local settings. The first step in predicting or modeling the presence of an etiological factor in animal populations, or the risk of infection in each area, is to fully understand the dynamics of the spatiotemporal epidemiology of the pathogen and the infection. All those infected or all those exposed to infection could pose a danger of importing RVFV-positive animals or RVFV vectors as carriers on farm-to-farm or national scale. The local community's interest will attract public awareness and support researchers and projects. Community involvement in supportive organizations such as environmental clubs, vocational centers, schools, and wildlife domesticated animals will also attract the attention of the local community regarding the methods of research, monitoring, and disease control. Further research is urgently needed to identify the pathogens present or to provide a genetic database. Livestock vaccines are available for use in endemic areas but approved vaccines for human use are lacking. Viruses have strong potential and capability of reassortment among strains, resulting in new and recombinant virus emergence. Similarly, the segmented RVFV genome can undergo reassortment with other strains and could emerge as a new virus strain with higher tolerance, more virulence, an extended host range, and effects on vector competence and this will further pose risks to vaccine effectiveness and application48. Effective, broad-spectrum, and affordable RVFV vaccines can be developed for mass vaccination of both humans and animals. A One Health approach can be implemented for the understanding of RVFV, and management strategies can be designed and developed for animal and human health49. A recent study conducted in cell lines demonstrated that RVFV can be transmitted to North African livestock and wildlife50. A rarely considered but potentially key vulnerability is that the neuronal system is negatively affected by RVFV infection in some arthropod vectors and a detailed and comprehensive study should be conducted12. Public awareness regarding the disease program could be designed and developed. Finally, upon encountering research conducted in the KSA on the pathogenesis or seroepidemiology of RVFV, caution is advised regarding the robustness of the study methods used due to the sociopolitical context of the country.

ConclusionBased on the latest data and the status of RVFV research, it is evident that RVFV is an endemic, emerging, and re-emerging threat that raises serious concern for public health, veterinary services, livestock and agriculture, industry, international trade of animals and animal products and the overall economy, not only in the KSA but also globally. Current prevention of RVFV largely relies on controlling vector populations and avoiding contact with infected animals. The pathogenicity of this virus is asymptomatic and self-limiting, and an early diagnosis of the virus is difficult in the current situation. Human vaccines are not yet available, and animal vaccines are limited to endemic regions. More detailed research, including a multisectoral and interdisciplinary approach, is urgently needed to understand the epidemiology, improve diagnostics, mass vaccination, ascertain virus transmission dynamics, unknown vectors, asymptomatic hosts, alternative reservoirs for the virus, and other factors responsible for virus re-emergence, spread and disease progression in the KSA. To control RVFV introduction and spread into new and previously unaffected areas, an ultra-dynamic and updated disease forecasting model can be designed and implemented through the collection of data from disease surveillance systems, veterinarians, health agencies, local communities and animal handlers, policy and decision makers, as well as other relevant stakeholders.

Finally, an effective disease management approach should be designed and developed by bringing together representatives from the ministries of health, agriculture and economic development, as well as clinicians, veterinarians, wildlife monitoring professionals, environmental and animal husbandry workers, policymakers, and disease prevention and control specialists. Sufficient funding for research and development should be allocated to generate detailed information to design, develop, and implement effective disease control measures in the near futuresoon not only in KSA but also globally.

CRediT authorship contribution statementSSS: data curation, writing original draft and final editing; AAZ: data curation, writing and editing; AAA: writing and editing; EIA: supervision, resources, funding acquisition and editing.

Ethics approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processAll authors declare that they have not used AI and AI-assisted technologies during the preparation of this MS.

FundingThis project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. 025/426. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Conflict of interestsNone declared.

The authors acknowledge the facilities provided by the Special Infectious Agents Unit, King Fahd Medical Research Centre, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.