Invasive meningococcal disease is associated with high fatality rates and disabling sequelae. The aims of this study were to describe the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of invasive Neisseria meningitidis isolates in Argentina, determine the genomic population structure and evaluate the potential coverage of vaccines targeting N. meningitidis serogroup B (MenB). During the period 2015–2022, a total of 444 isolates of N. meningitidis causing invasive disease were assessed through laboratory surveillance; 344 isolates were available for whole genome sequencing characterization. The presence of antimicrobial resistance genes, and the distribution of clonal complexes and vaccine antigens were analyzed. MenB was the most frequent serogroup (53.2%), followed by MenW (32.0%). Most isolates were susceptible to the antimicrobial agents tested; however, 56.7% exhibited intermediate resistance to penicillin. MenB showed wide genetic diversity and was mainly associated with ST-865 cc, ST-35 cc, ST-41/44 cc, and ST-32 cc. Unlike other countries, in Argentina, ST-865 cc was one of the major clonal complexes associated with MenB, MenW was only associated with ST-11 cc. To study the potential coverage of vaccines targeting MenB, we used the MenDeVAR (Meningococcal Deduced Vaccine Antigen Reactivity) index, which provides information on the presence and possible immunological cross-reactivity of the different vaccine antigenic variants. MenDeVar showed 19.3% vaccine reactivity for 4CMenB and 40.0% for the bivalent vaccine. Laboratory surveillance is essential for generating evidence-based decisions for updating vaccination strategies.

La enfermedad meningocócica invasiva se asocia con alta mortalidad y secuelas incapacitantes. Los objetivos de este estudio fueron describir las características fenotípicas y genotípicas de aislados invasivos de Neisseria meningitidis en Argentina, determinar la estructura genómica y evaluar la cobertura potencial de vacunas dirigidas a Neisseria meningitidis serogrupo B (MenB). De los 444 aislados de N. meningitidis causantes de enfermedad invasiva colectados durante el período 2015-2022, 344 estuvieron disponibles para su caracterización por secuenciación de genoma completo. Se analizó la presencia de genes de resistencia a los antimicrobianos y la distribución de complejos clonales y antígenos vacunales. El MenB fue el serogrupo más frecuente (53,2%), seguido por MenW (32,0%). La mayoría de los aislados fueron sensibles a los agentes antimicrobianos probados. aunque el 56,7% presentó resistencia intermedia a la penicilina. El serogrupo MenB mostró una amplia diversidad genética y se asoció, principalmente, a ST-865 cc, ST-35 cc, ST-41/44 cc y ST-32 cc. ST-865 cc fue uno de los complejos clonales mayoritarios asociados a MenB a diferencia de lo que ocurre con los aislados invasores de otros países. MenW solo se asoció con el ST-11 cc. Para estudiar la cobertura potencial de las vacunas dirigidas a MenB, se utilizó el índice MenDeVAR (Meningococcal Deduced Vaccine Antigen Reactivity). Dicho índice mostró reactividad vacunal del 19,3% para la vacuna 4CMenB y del 40,0% para la vacuna bivalente. La vigilancia de laboratorio es esencial para la toma de decisiones relacionadas con la actualización de las estrategias vacunales.

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is a rare but potentially fatal condition caused by Neisseria meningitidis, a Gram-negative encapsulated diplococcus that exclusively infects humans76. It is characterized by high fatality rates, ranging between 4 and 20% in patients receiving adequate antibiotic treatment92. Between 10 and 20% of survivors experience disabling sequelae, mainly hearing loss or limb amputation66. The recommended empirical treatment of IMD are third-generation cephalosporins. Ciprofloxacin, rifampicin or ceftriaxone are recommended for chemoprophylaxis in contacts of patients with meningococcal disease, or azithromycin in case of resistance to ciprofloxacin54. Fortunately, N. meningitidis has remained largely susceptible to all these antimicrobial agents. However, in the United States, the number of cases caused by penicillin- and ciprofloxacin-resistant strains has increased in recent years, largely associated with serogroup Y7. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in N. meningitidis is mandatory, since empirical treatments and drugs useful for prophylaxis in each region are established based on these results. The most common clinical manifestations are meningitis, sepsis or an association of both; less frequent manifestations include pneumonia, septic arthritis and pericarditis. Other unusual clinical presentations have been reported in recent years associated with the emergence of hypervirulent clones23.

Nm is an obligate commensal organism of the human upper respiratory tract, the only known reservoir, and usually colonizes the nasopharynx, a phenomenon known as carriage. The carrier state may be transient without affecting the host or evolve into invasive disease. Carriage is necessary for the disease to occur16. Between 10 and 35% of healthy adolescents and young adults harbor N. meningitidis in the nasopharynx16,38.

The capsular polysaccharide of N. meningitidis is the main virulence factor. Based on its chemical composition and immunological specificity, N. meningitidis strains are classified into 12 serogroups: A, B, C, E, H, I, K, L, W, X, Y, and Z42. Serogroups A, B, C, W and Y are the predominant cause of IMD worldwide, and the frequency and geographic distribution vary widely75. Serogroups E and Z rarely cause disease, generally in patients with immunodeficiencies, while non-encapsulated strains are infrequently invasive36,79. Although IMD is endemic, outbreaks or epidemics occur mainly due to serogroups X or W56,71,73.

Invasive disease is produced by a limited number of hypervirulent lineages15. The epidemiology is dynamic and unpredictable, with cyclic changes in the prevalence of serogroups70.

In Latin America, the incidence of IMD varies from <1/100000 inhabitants in Mexico to 1.9/100000 in Brazil90. In Argentina, the incidence was 0.46/100000 in 2010, reaching a peak of 0.7/100000 in 2013 caused by an increase in serogroup W cases associated with the hypervirulent clone ST-1152. By 2019, the rate had decreased to 0.22/10063 and fell further to 0.05/100000 in 2020–2021 due to the preventive measures implemented to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, the incidence rose to 0.12/100000 individuals60.

Invasive meningococcal disease occurs most commonly in infants (<1 year) followed by children aged 1–4 years; some countries have a peak incidence in adolescents46.

In Latin America, serogroups C (MenC), B (MenB) and W (MenW) prevail although geographic distribution differs among countries90. In Argentina, the most frequent serogroups were B and W in the period 2010–2019. Since 2015, there has been a noticeable rise in the proportion of MenB63, which remains predominant to date (unpublished observation, 2024).

Notification of IMD cases is mandatory in Argentina and conducted through the Argentine Integrated Health Information System (SISA). The National Reference Laboratory (NRL) of the Central Nervous System, Respiratory and Systemic Bacterial Infections Network performs passive surveillance of IMD. This reference laboratory, which is also part of the Network Surveillance System for the Causative Agents of Pneumonia and Meningitis (SIREVA II) program of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), receives all invasive N meningitis isolates from a network of laboratories around the country.

Invasive meningococcal disease caused by the most common serogroups can be prevented through immunization. Quadrivalent (ACYW) conjugate polysaccharide vaccines and more recently pentavalent vaccines (ACYWX) are currently available62. Polysaccharide-based vaccines that elicit adequate immune responses against reference strains are likely to protect against all strains belonging to the same serogroups because the capsular polysaccharide structure within serogroups is highly conserved11. However, the MenB capsular polysaccharide is poorly immunogenic because it exhibits cross-reactivity with human brain glycoproteins; therefore, outer membrane proteins are used as alternative antigens for vaccine design35. Due to the wide genetic diversity within isolates, the development of vaccines targeting MenB is complex. Vaccine antigens may vary in their sequence and level of expression on the bacterial surface among isolates, hence vaccine coverage should be monitored and updated regularly11. The most common clonal complexes (ccs) detected in the world are ST-41/44 cc, ST-32 cc, ST-269 cc, ST-213 cc, ST-162 cc, ST-35 cc, ST-461 cc and ST-213 cc, with differences in proportions between countries11,51,62,77. Previous studies have shown that the distribution of ccs among invasive MenB strains in Argentina differs from that reported in other countries. Predominance of the ST-865 cc was observed over time, while in the rest of the world this cc only causes sporadic cases of IMD29,86. This finding is important for the assessment of vaccine coverage since protein antigens differ between ccs29.

Two recombinant MenB vaccines have been licensed in several countries around the world: the multicomponent vaccine 4CMenB (Bexsero®, GSK) and the rLP2086 bivalent vaccine (Trumenba®, Pfizer). Bexsero® comprises four proteins: factor H binding protein (fHbp) peptide 1 from subfamily B/variant 1, Neisserial adhesin A (NadA) peptide 8 variant NadA-2/3, Neisserial heparin-binding antigen (NHBA) peptide 2 and PorA P1.7–2,4 from the New Zealand epidemic strain84. Trumenba® is based on two fHbp antigens, namely peptide 45 from subfamily A/variant 3 and peptide 55 from subfamily B/variant 165.

Bexsero is the only MenB vaccine with real-world evidence demonstrating a reduction in invasive meningococcal disease cases without safety issues. By 2022, this vaccine was licensed in 45 countries, 33 of which have clinical recommendations, and is used in different age groups, namely infants, children and adolescents, or in high-risk groups85. In 2015, the UK was the first country to introduce Bexsero into its National Immunization Program (NIP), providing evidence of real-world performance in a NIP48.

Bexsero is generally recommended in individuals from the age of 2 months, except in the US where it is authorized for use in individuals aged 10–25 years. Trumenba is generally recommended for children aged 10 years or older. Thus, Bexsero is the only broad coverage MenB vaccine that is currently used in infants, the age group with the highest incidence85. Nine countries had included Bexsero in their NIP by 202185. In Latin America, Chile is the only country that has incorporated Bexsero in its NIP, and Brazil and Argentina have clinical recommendations91. In 2017, Argentina introduced the quadrivalent conjugate vaccine MenACWY-CRM197 (Menveo®) into its NIP for infants in a 2+1 schedule (at 3, 5 and 15 months) and adolescents (single dose at eleven years of age)24. Although Bexsero was licensed in Argentina in 2017, it has not been included in its NIP to date. However, in 2020, the combined use of Menveo® and Bexsero® was recommended for specific risk groups25. Trumenba® is not available for use in Argentina.

The development and licensure of anti-meningococcal vaccines are not based on clinical efficacy trials because these trials are not feasible due to the low incidence of IMD34. Licensure is based on serological correlates of protection that associate a threshold titer of serum bactericidal activity with protection22.

The human serum bactericidal assay (hSBA) is considered the gold standard for assessing meningococcal vaccine efficacy. However, this method is not practical for use in public health settings because of issues related to limited resource availability, time and qualified staff restrictions, and the required serum volume, particularly in infants10. Hence, other methods were developed as complementary tools to predict Bexsero coverage.

Initially, the Meningococcal Antigen Typing System (MATS) was created to assess the level of Bexsero strain coverage9,26. This phenotypic method combines the sequence of the PorA gene segment coding for the variable 2 region (VR2) with three sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) against each of the three Bexsero recombinant proteins (fHbp, NHBA and NadA), both measuring immunological cross-reactivity and quantifying the expression of the three antigens. Coverage prediction is based on the presence of VR2-4 or the expression levels of any of the three antigens exceeding a positive bactericidal threshold value. Due to the constant evolution of MenB strains, the sequence and level of expression of the four Bexsero components in disease-causing isolates may vary, consequently MATS prediction must be reassessed regularly to ensure that it reflects the current epidemiological trend. Recently, a decrease in the potential predicted coverage of MenB strains by Bexsero has been observed in some European countries72. Moreover, MATS does not account for a potential synergistic effect for two or more vaccine components, nor for OMV components other than PorA, which underestimates strain coverage compared to assessment by hSBA11.

To evaluate the coverage of the Trumenba® vaccine, the meningococcal antigen surface expression (MEASURE) assay was developed, which measures the expression of fHbp for both subfamily A and B isolates by flow cytometry58. However, this assay does not assess genetic diversity, and therefore does not consider antigenic cross-reactivity among fHbp subfamilies/variants. Another limitation is that, as with hSBA and MATS, viable bacteria are needed.

In order to facilitate the evaluation for clinical and public health purposes, the Meningococcal Vaccine Deduced Antigen Reactivity (MenDeVar) Index was developed combining genomic and experimental data from published sources (publicly available in PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org))47. This index uses whole-genome sequences or individual gene sequences, obtained from IMD isolates or clinical specimens, to deliver rapid evidence-based information on the presence and possible immunological cross-reactivity of different meningococcal antigen variants included in the Bexsero and Trumenba vaccines47,78. In addition, the MenDeVAR index allows professionals who are not genomics specialists to evaluate the potential reactivity of vaccines in individual cases, outbreak control, or assessment of public health vaccination programs. However, the method has limitations as it combines whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and published in vitro test data (MATS, MEASURE and hSBA), some of which may not be appropriate correlates of protection78. Nonetheless, WGS is currently the most cost-effective method used to identify N. meningitidis isolates for epidemiological surveillance purposes, assessment of potential coverage of protein-based vaccines and changes in antigen prevalence14.

The aims of this study were to describe the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of invasive N. meningitidis isolates in Argentina, determine the genomic population structure and evaluate the potential coverage of vaccines targeting MenB.

Materials and methodsStudy descriptionA descriptive and observational study was conducted.

Data collectionDemographics and clinical data were collected from the epidemiological records accompanying the isolates referred to the NRL and categorized by age group, geographical area and clinical manifestations. Five regions were considered for the analysis of the geographical areas: Central (Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Entre Ríos and Santa Fe provinces), Northeastern (NE: Chaco, Corrientes, Formosa and Misiones provinces), Northwestern (NW: Catamarca, La Rioja, Jujuy, Salta, Santiago del Estero and Tucumán provinces), Cuyo (Mendoza, San Juan and San Luis provinces) and Southern (Chubut, La Pampa, Neuquén, Río Negro, Santa Cruz and Tierra del Fuego provinces) (Table S1).

N. meningitidis isolatesBetween January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2022, a total of 444 isolates were collected from sterile sites in 444 patients of all ages with IMD and referred to the NRL through the National Laboratory Network.

Identification and genogrouping of N. meningitidis isolatesIsolates were subcultured onto brain heart infusion agar containing 10% horse blood supplemented with 1% Isovitalex (BBLTM), and incubated in 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for 18–24h. Identification was confirmed at the NRL by Gram staining, oxidase reaction (Britania, Argentina), gamma-glutamyl aminopeptidase reaction (ROSCO, MEDICA-TEC, Argentina), matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry MALDI-TOF (Brucker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and by PCR using specific primers to detect the crgA gene87 involved in the adhesion of N. meningitidis to target cells, and ctrA41, a capsule transport gene. Capsular groups were determined by PCR with specific capsular primers6,87. Additionally, ctrA negative strains were tested for the presence of capsule null region (cnl)17.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testsMinimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) tests for penicillin, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, rifampicin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin and azithromycin were performed by the agar dilution method and interpreted according to CLSI guidelines18.

Whole genome sequencing characterizationA total of 344 isolates were sequenced by whole-genome sequencing. DNA extraction was carried out using a manual extraction kit following the manufacturer's specifications (QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit 5, Qiagen, Germany). Library preparation was conducted using the Illumina Covidseq kit (Illumina Inc. CA, USA). Pooled libraries were sequenced on Illumina platforms (MiSeq or NovaSeq). After quality control and trimming, paired-end reads were de novo assembled using the Unicycler pipeline (v0.4.8)93.

The capsular group of each genome was determined based on the presence of capsular specific genes55. Isolates that contained capsule genes but lacked identifiable specific capsule genes were classified as “non-groupable” (NG). Isolates lacking the whole-capsule locus were defined as capsule null (cnl).

The penA gene, which encodes penicillin-binding protein 2 was examined. The Quinolone Resistance-Determining Region (QRDR) of quinolone resistance-associated gyrA and parC genes (encoding gyrase and encoding topoisomerase I, respectively) was analyzed.

Assembled contigs were submitted to the PubMLST Neisseria database for genotyping47. Allele and peptide sequence identification of different genes was performed using the automated web-based sequence tagging implemented in PubMLST. Isolates were assigned to a sequence type (ST) based on the allelic profile of seven MLST genes. Related STs are grouped into a clonal complex (cc) and STs not associated with a cc are considered singletons. Novel alleles and STs were submitted to the PubMLST database for curation.

The porB alleles and the variable regions of porA (VR1 and VR2) and fetA were also determined for fine typing purposes. The different variants of porA were described using the “P1.VR1,VR2” format. Peptide variants of vaccine antigen genes (fHbp, NHBA, and NadA) were identified. The Novartis nomenclature was used to classify the fHbp peptides into the three variant families: variants 1, 2 and 3. New gene and peptide variants were scanned manually, and after curator approval and annotation, were added to the PubMLST database. For NHBA typing, both nucleotide alleles (NEIS2909) and peptide variants were defined. NadA peptides were classified into NadA variant families 1, 2/3 or 4/5, according to a previous work from Novartis5. NadA was considered to be missing when the gene was not detected in the assembly or was interrupted by an insertion sequence.

The potential coverage of MenB vaccines was assessed by analyzing the antigenic profile through the Meningococcal Deduced Vaccine Antigen Reactivity (MenDeVAR) index. The four categories used to describe the potential coverage of a given isolate were: “exact match”, “cross-reactive”, “none” and “insufficient data”, as previously described78.

PhylogenyWhole-genome sequencing data was further analyzed using Roary (v3.12.0)68. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the core genome were extracted using SNP-sites (v2.3.3)69. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE (v1.6.1)64. To perform cluster assignment, the core-genome SNP alignment (129718 SNPs) was analyzed using a hierarchical Bayesian clustering algorithm implemented in Fastbaps v1.0, considering its speed and accuracy88.

Data availability statementNucleotide sequences were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under Bioproject PRJNA1124021. Accession numbers are listed in Table S2.

Statistical analysisUnivariate analysis was performed for each variable and results were presented as absolute and relative (%) values. The median (Me) was used as a measure of central tendency and interquartile range (IQR) as measure of dispersion.

To evaluate the categorical variables in different groups or the association between them, the chi-square (χ2) statistic was used with its corresponding degrees of freedom.

When more than two groups were compared, multiple comparisons were performed adjusting the p-value according to Bonferroni. p=0.05 was used for comparisons. The statistical analysis was performed using R Statistical Software (R Core Team 2023, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/).

ResultsDemographics, clinical presentation and phenotypic characterizationA total of 444 N. meningitidis isolates from 444 cases of IMD were received at the NRL.

Age ranged from 0 to 1104 months (92 years) (Me=36, IQR 8–192), and was distributed in the following age groups: <1 year 28.8% (n=127), 1–4 y 26.8% (n=118), 5–9 y 11.3% (n=50), 10–19 y 11.3% (n=50), 20–39 y 8.8% (n=39), 40–59 y 7.9% (n=35) and ≥60 y 5.0% (n=22). Age information was missing in 3 cases (Table S1).

Distribution according to clinical presentation was: meningitis 53.8% (n=239), meningococcemia 18.5% (n=82), meningitis with meningococcemia 13.3% (n=59), bacteremia 9.5% (n=42), arthritis 2.0% (n=9), pneumonia 1.8% (n=8) and others 1.1% (n=5) represented by cellulitis (n=2), thyroglossal cyst infection (n=1), bartholinitis (n=1) and neck abscess (n=1) (Table S1).

Clinical presentation differed by age group. Pneumonia was more common in patients aged ≥60 y, (27.3% (6/22)) than in those aged <60 y, (0.5% (2/419)) (χ2=69.9, p<0.001), as was bacteremia, 27.3% (6/22) in ≥60 y vs 8.6% (36/419) in <60 y (χ2=6.4, p=0.01). Nine isolates corresponded to patients with arthritis, all of whom were children aged ≤4 years.

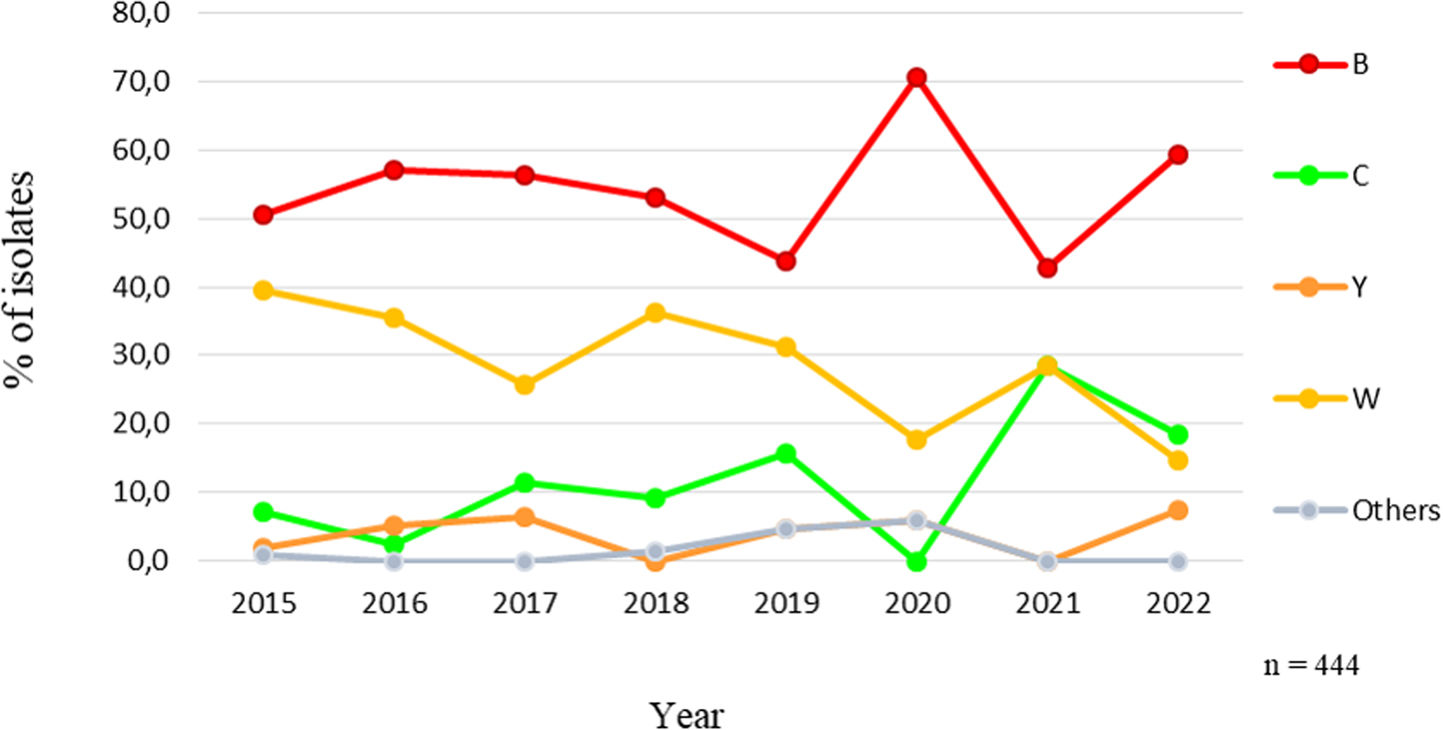

Throughout the study period, MenB predominated followed by MenW, except in 2022 when MenC represented 18.5% (5/27) and MenW 14.8% (4/27). In 2015, the proportion of MenB was 50.5% (50/99), rising to 59.3% (16/27) at the end of the study period. A significant increasing trend of MenC (p=0.048) and a significant decreasing trend of MenW (p<0.001) were observed (Fig. 1).

The distribution of isolates by capsular groups showed that MenB accounted for 53.2% (n=236), followed by MenW 32.0% (n=142), MenC 9.7% (n=43), MenY 3.8% (n=17), cnl 0.5% (n=2) and MenE 0.2% (n=1).

The remaining 0.7% corresponded to 3 isolates, in which the capsular group could not be defined (ND); these isolates harbored different types of deletions in region A of the capsular locus.

MenW predominated in patients aged >60 y (54.5%; 12/22) compared to ≤60 y (30.8%; 129/419) (χ2=4.4, p=0.036). It also prevailed in non-meningeal clinical manifestations (38.5%; 79/205) compared to meningitis (26.4%; 63/239) (χ2=9.6, p=0.001).

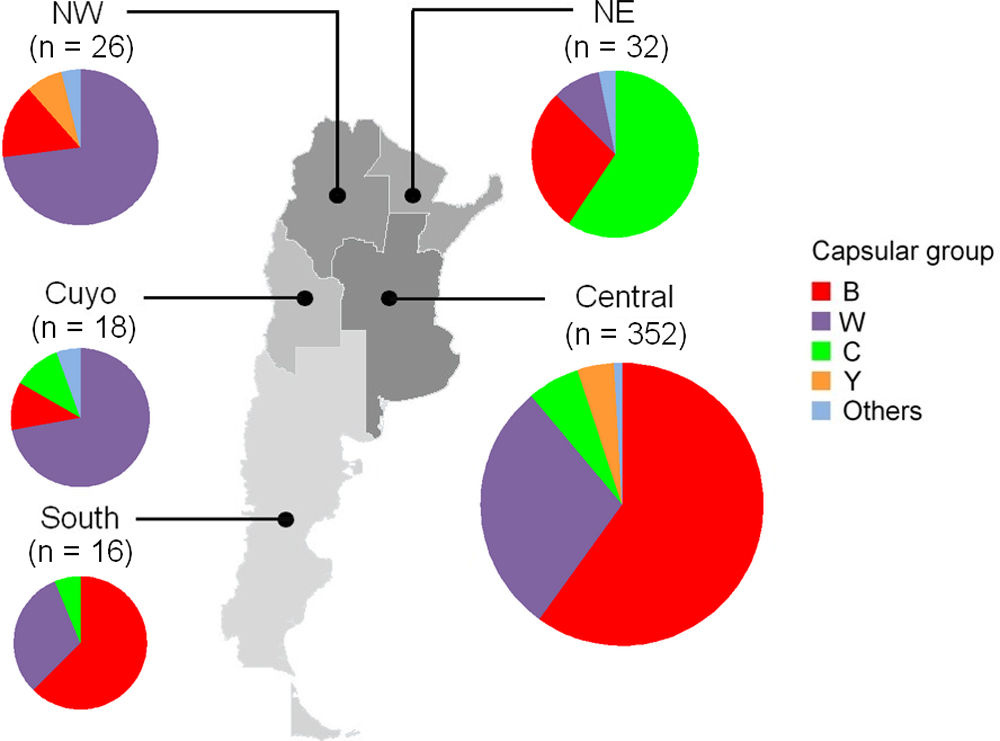

The geographical distribution of isolates was as follows: 79.3% (n=352) were from the Central area, 7.2% (n=32) NE, 5.9% (n=26) NW, 4.1% (n=18) from Cuyo and 3.6% (n=16) from the Southern region. MenB predominated in the Central, 59.9% (211/352) and Southern 62.5% (10/16) regions, while MenC prevailed in the NW 59.4% (19/32) and MenW was the most common capsular group in the NW and Cuyo regions, 73.1% (19/26) and 72.2% (13/18) respectively. These differences were significant in all cases (χ2=20.6, p<0.001) (Fig. S1).

All isolates remained susceptible to ceftriaxone, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, rifampicin and azithromycin. However, 56.7% (223/393) and 63.9% (251/393) exhibited intermediate resistance to penicillin (MIC 0.12–0.25mg/l) and ampicillin (MIC 0.25–1mg/l), respectively (Table S3). For penicillin, MIC50 was 0.12mg/l and MIC90 0.25mg/l; none of the isolates showed an MIC >0.25mg/l. Isolates with intermediate resistance to penicillin were B, 65.0% (n=145); W, 17.5% (n=39); C, 13.0% (n=29), and Y, 3.1% (n=7). The remaining three were E, cnl and ND.

Five isolates were non-susceptible to ciprofloxacin, four were resistant with MICs 0.12–0.25mg/l and one showed intermediate resistance with an MIC of 0.06mg/l, exhibiting nalidixic acid disk inhibition zones between 6 and 16mm. Two of these isolates were MenB, two MenW and one cnl, none of which were associated with any specific clonal complex (Table S3).

Molecular characterizationFrom the total of 444 isolates received at the NRL between 2015 and 2022, 77.5% (n=344) were available for analysis by WGS. The proportion of sequenced isolates by capsular group were: B, 72.5% (171/236), C, 71.1% (32/45), Y, 100% (17/17), W, 85.7% (120/140), ND (3/3) and cnl (1/2).

Antimicrobial resistanceAnalysis of the penA sequences revealed the presence of 58 alleles, with great diversity in both penicillin-susceptible and intermediate isolates. The penA_59 allele was the most common among the penicillin-susceptible strains identified in 58/154 (37.7%), all were MenW and ST-11 cc. On the other hand, penA_392 was the most frequent among the penicillin-intermediate isolates (39/181; 21.5%), mainly associated with MenB ST-865 cc. However, no correlation between MICs and specific sequences was observed.

Mutations in the QRDR of the gyrA gene were detected in the five ciprofloxacin non-susceptible isolates (Table S4). No mutations were found in the QRDR of the parC gene.

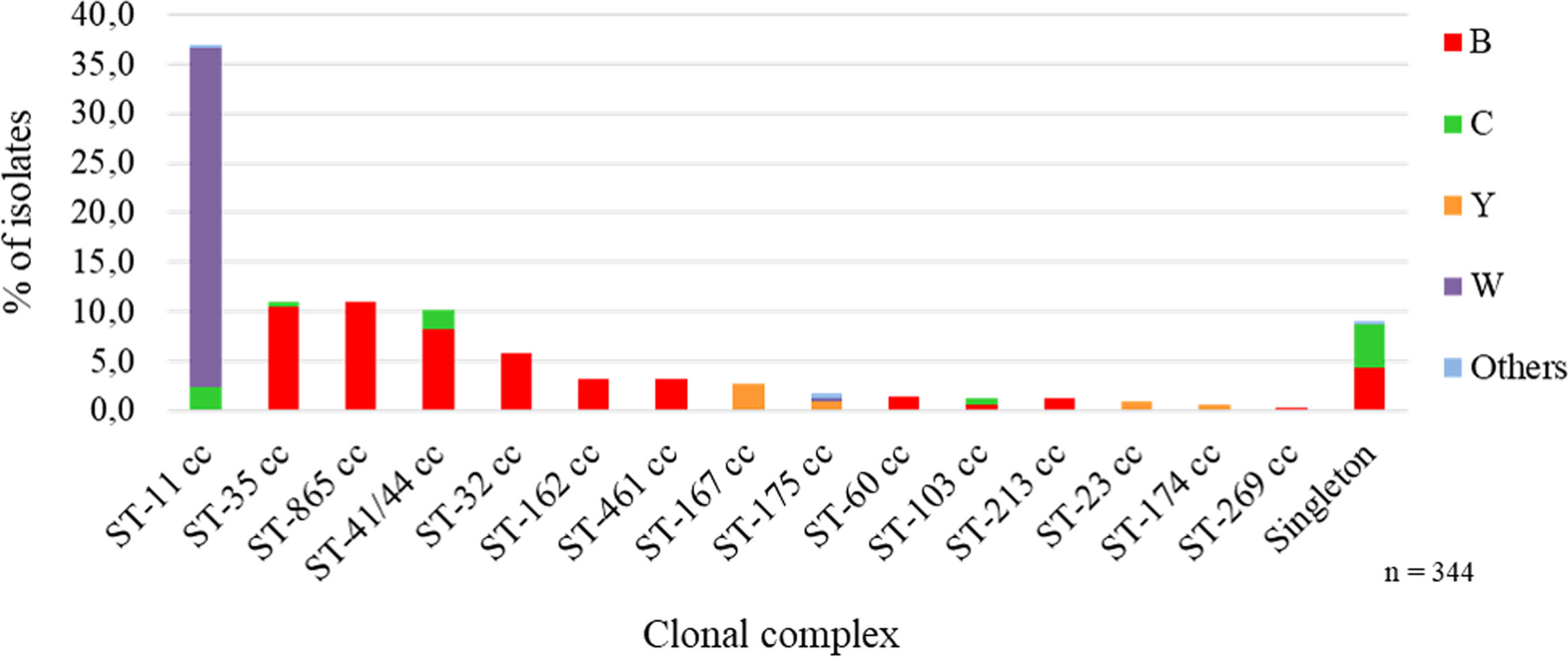

Distribution of clonal complexesFifteen clonal complexes (cc) were identified, with the most frequent being ST-11 cc 36.9% (n=127) followed by ST-865 cc 11.0% (n=38), ST-35 cc 11.0% (n=38) and ST-41/44 cc 10.2% (n=35). Thirty-one singletons were found, 10 of which were assigned through this laboratory surveillance (Table S2).

We analyzed the association between capsular groups and clonal complexes. MenB showed high heterogeneity and mainly belonged to four clonal complexes: ST-865 cc 22.2% (38/171), ST-35 cc 21.1% (36/171), ST-41/44 cc 16.4% (28/171) and ST-32 cc 11.7% (20/171), while MenW was solely associated with ST-11 cc 100% (120/120). MenC was distributed between singletons in 15 of 32 isolates (46.9%), 7 of which were ST-41/44 cc (21.9%) and 6 ST-11 cc (18.8%); most singletons were represented by ST-2196 (14/15, 93.3%), endemic to the province of Chaco. MenY isolates largely belonged to ST-167 cc 52.9% (9/17) (Fig. 2 and Table S2).

In all age groups, except for the 5–9-year group, a significant predominance of ST-11 cc was observed compared to other ccs (Table S5A).

In the Central, Cuyo and NW regions, a predominance of ST-11 cc associated with MenW was observed, while in the NE and Southern regions, there were no significant differences regarding the distribution of ccs (Table S5B).

Association between clonal complexes and sequence typesThe main associations were: ST-11 cc to ST-11 (96.9%, 123/127), ST-865 cc to ST-3327 (86.8%, 33/38), ST-35 cc to ST-35 (89.4%, 34/38), ST-461 cc to ST-1946 (72.7%, 8/11), ST-162 cc to ST-9293 (63.6%, 7/11), ST-167 cc to ST-1624 (100%, 9/9), and ST-60 cc to ST-7983 (80.0%, 4/5) (Table S2).

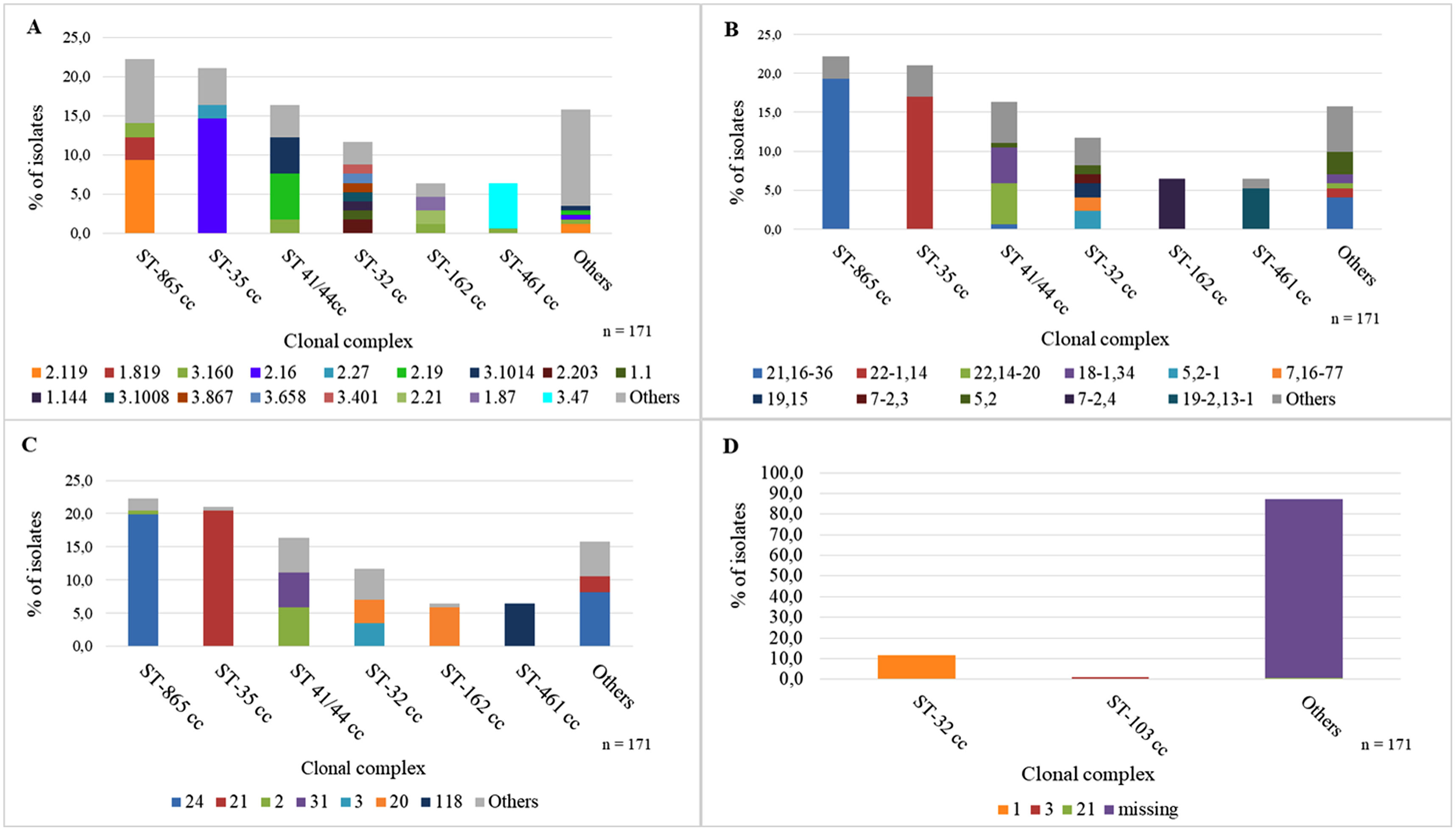

PorA distributionPorA showed high heterogeneity with 48 VR1-VR2 combinations. Among the MenB isolates, the main associations between cc and PorA were: ST-865 cc to P1.21,16-36 (86.8%, 33/38) and ST-35 cc to P1.22-1,14 (80.6%, 29/36) (Fig. 3A).

Among MenW, 95.8% (115/120) of the ST-11 cc isolates exhibited P1.5,2. In the MenC isolates, ST-11 cc was associated with P1.5-1,10-8 (6/6), and ST-2196 to P1.21.4 (14/14). MenY ST-167 cc was only associated with P1.5-1,10-4 (9/9) (Table S6).

fHbp distributionMenB isolates showed heterogeneity in the distribution of variant families: variant 2 predominated (43.3%, 74/171) followed by variant 3 (29.8% (51/171) and variant 1 (20.5%, 35/171).

ST-865 cc was generally associated with fHbp peptide 2.119 (42.1%, 16/38) and ST-35 cc to peptide 2.16 (69.4%, 25/36) (Fig. 3B). MenW ST-11 cc was strongly associated with fHbp peptide 2.22 (97.5%, 117/120). MenC also showed high diversity in variant family distribution and variant 2 prevailed (53.1%, 17/32). Among MenY, 88.2% (15/17) of the isolates belonged to variant 2 and the main association observed was ST-167 cc to fHbp peptide 2.23 (9/9) (Table S7).

Thirteen new alleles not assigned to peptides were found (Table S2).

NHBA distributionAmong the MenB isolates, the most frequent NHBA peptides were 24 and 21. ST-865 cc was associated with NHBA peptide 24 (89.5%, 34/38) and ST-35 cc with NHBA peptide 21 (97.2%, 35/36) (Fig. 3C).

Most MenW isolates exhibited NHBA peptide 29 (97.5%, 117/120). MenC showed the following main associations: ST-11 cc with NHBA peptide 20 (6/6), ST-41/44 cc with NHBA peptide 1 (6/7) and ST-2196 with NHBA peptide 53 (14/14). Finally, among the MenY isolates, the most important association was ST-167 cc with NHBA peptide 9 (8/9) (Table S8).

Thirty-nine NHBA peptides were found, 13 of which had not been previously assigned.

NadA distributionNadA peptide was found in 42.2% (145/344) of the isolates and in only 13.5% of the MenB isolates (23/171). The most important association was ST-32 cc with NadA peptide 1, 100% (20/20) (Fig. 3D).

NadA was identified in 99.2% (119/120) of the MenW isolates and mostly corresponded to peptide 6 (97.5%, 117/120). NadA was absent from the MenC isolates and among the MenY isolates, only 11.8% exhibited NadA (2/17) (Table S9).

PorB allele distributionTwenty-four different alleles of PorB-2 and 46 of PorB-3 were found, 52 of which were new alleles. Among the MenB isolates, the main associations with ccs were ST-865 cc with PorB 3-350 (76.3%, 29/38) and ST-35 cc with PorB 3-63 (75.0%, 27/36).

MenW was associated with PorB 2-244 (85.0%, 102/120). In MenC, ST 41/44 cc was largely associated with PorB 3-39 (6/7) and ST-2196 with PorB 3-40 (14/14). In MenY, the main association was ST-167 cc with the new allele PorB 3-6048 (7/9) (Table S10).

FetA VR distributionThirty-six FetA VR alleles were identified. Among the MenB isolates, ST-865 cc was most often associated with F5-8 (71.1%, 27/38) and ST-35 cc with F1-1 (36.1%, 13/36) and F4-1 (33.3%, 12/36).

F1-1 was most commonly found (96.7%, 116/120) in the group of the MenW isolates. In MenC, ST 41/44 cc was associated with F5-2 (6/7) and ST-2196 with F1-5 (14/14). Among the isolates belonging to MenY, ST-167 cc was associated with F3-4 (9/9) (Table S11).

Potential MenB vaccines coverage prediction through the MenDeVar indexIn total, 19.3 of the MenB isolates exhibited reactivity with Bexsero®, 14.6% (25/171) corresponded to an exact match and 4.7% (8/171) to cross-reactivity. Exact match was due to the fHbp allele 1 present in ST-32 cc, NHBA peptide 2 mainly associated with ST-41-44 cc, and PorA VR2 4 mostly found in ST-162 cc presenting PorA 7-2,4. Cross-reactivity was due to the presence of fHbp alleles 14, 15, 144, and 215, NHBA peptide 1 and NadA peptide 3. A large number of the MenB isolates 78.9% (135/171) belonged to the insufficient data category (Tables S2 and S12).

For Trumenba®, an exact match was found in only 1 of 171 MenB isolates (0.6%), due to the presence of the fHbp 45 allele, and cross-reactivity was identified in 64 isolates (37.4%) due to the following fHbp alleles: 1 and 13 associated with ST-60 cc; 14, 15 and 16, mainly associated with ST-35 cc; 19, mostly associated with ST-41/44 cc; 21, present in ST-162 cc; 25, associated with ST-103 cc; 47, found in ST-461 cc, and 87 harbored in ST-162 cc. The remaining 106 MenB isolates (62%) were classified into the insufficient data category (Supplementary Tables S2 and S12).

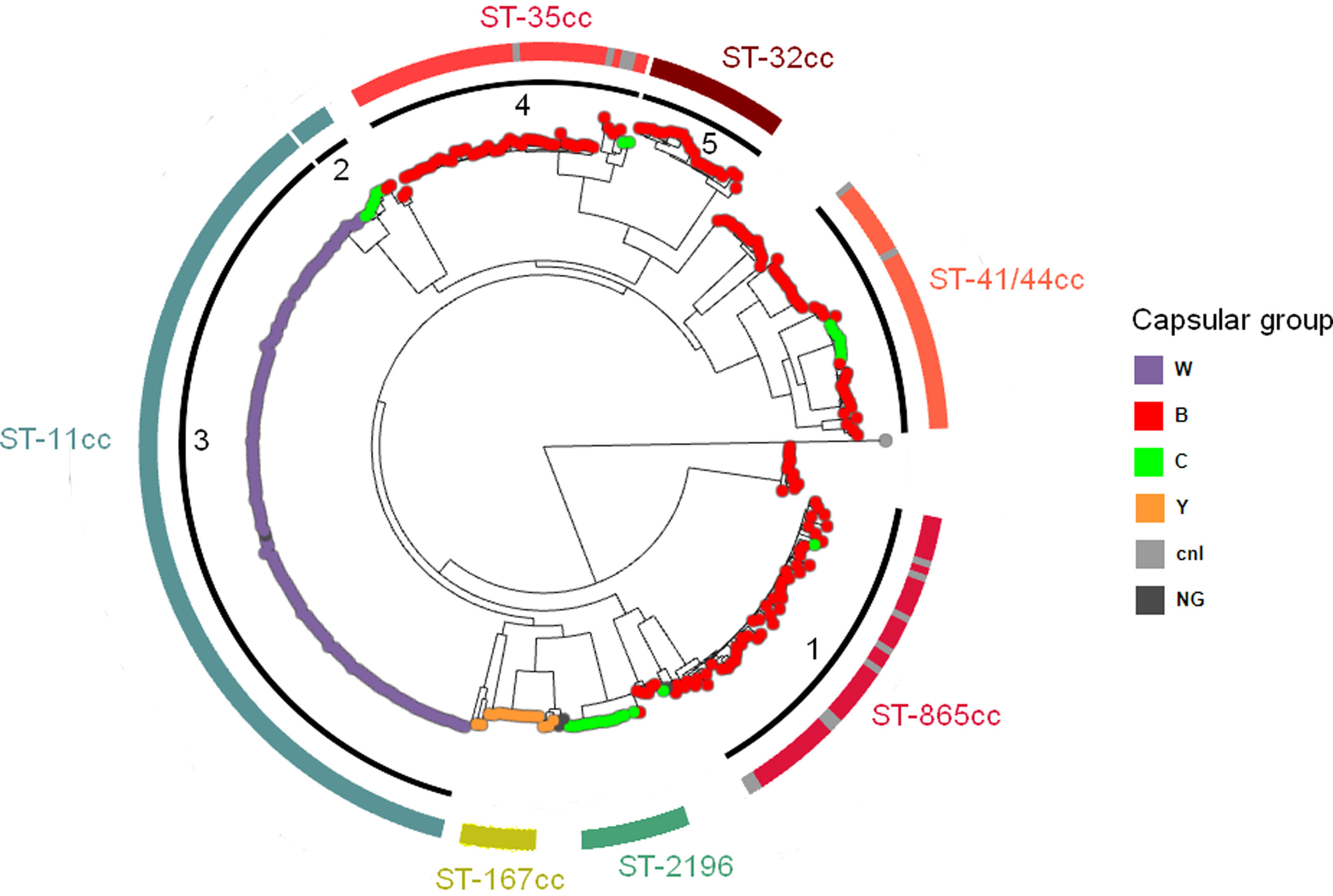

Phylogenetic analysisThe clustering of the 344 genomes based on 129718 core genome SNPs using Fastbaps identified five genetically distinct subclades (clusters 1–5) and one group of heterogeneous isolates (Fig. 4). Clusters 1, 4 and 5 predominantly comprised MenB isolates belonging to ST-865 cc, ST-35 cc and ST-32 cc, respectively. Many of the singletons detected in this study grouped within these clusters. MenW and MenC ST-11 cc isolates were separated into two subclades and assigned to clusters 3 and 2, respectively. MenC ST-2196 isolates formed a different clade from the other MenC isolates detected in this study (https://microreact.org/project/m7T3fQwa5myCHgDaU4hKnD-nm2015-2022).

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the core genome alignment of 344 N. meningitidis isolates. Argentina, 2015–2022. Capsular groups are indicated by the color of the isolates. Fastbaps clusters are displayed in the inner black rings (clusters 1–5). Major clonal complexes are represented in the outer colored rings. Singletons within a cluster are shown in grey. (cnl=capsule null locus, NG=non-groupable).

A total of 444 N. meningitidis isolates from IMD cases were assessed at the NRL. Meningitis was the most common clinical manifestation, followed by meningococcemia and less frequently the association of both, as described in the literature27,80.

Among other uncommon clinical presentations, an unusual case of bartholinitis was reported, which to our knowledge, is the first to be described worldwide (personal communication, 2024).

Infants under 1 year old have the highest reported incidence rates of IMD37,70. In our study, the highest proportion of isolates corresponded to infants <1 year followed by young children aged 1–4 years, while we did not observe an increase in the proportion of cases in adolescents. Prior active surveillance studies of IMD in Argentina did not show a peak in incidence in adolescents as reported in other countries24,63,70. However, we should be careful when comparing our results to those published in the literature since we only analyzed data acquired via passive surveillance.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the average number of IMD cases has decreased in most countries around the world due to control and lockdown measures2,60. A similar reduction in the number of isolates was observed in our study.

The circulation of serogroups is cyclic75. Throughout the study period, MenB predominated in Argentina. However, previous data showed that in the period 2008–2013, MenW was more prevalent, reaching its highest frequency in 201230,39. In 2014, similar proportions of both serogroups were reported and since 2015, a sustained increase in MenB over time and a significant decrease in MenW were observed63.

The distribution of serogroups varies geographically, not only across countries but also across different regions within a country75. Although MenB was overall the most common strain found during the study period, the distribution of capsular groups by region within the country differed. MenB predominated in the Central and Southern regions, while MenC prevailed in the NW and MenW in the NW and Cuyo regions.

In Latin America, MenC historically predominated in Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela67,90. After the introduction of the meningococcal C conjugate vaccine (MCC) in Brazil's NIP, the incidence of invasive disease caused by this serogroup decreased and MenB became more prevalent45,83. In Colombia, between 1987 and 2015, MenB was prevalent; however, since 2016, MenC has increased in frequency accounting for 67.2% of isolates in the period 2016–201861. In Chile, MenB predominated until 2011 and subsequently, a significant increase in MenW cases associated with the hypervirulent ST-11 clone was observed. After a MenW outbreak in 2014, immunization with quadrivalent (ACYW) meningococcal conjugate vaccines was implemented in toddlers. Since 2019, MenB cases have increased and become predominant again, while MenW cases have decreased77,91. In Uruguay, MenB prevailed between 2010–2019 while MenW had lower stable frequencies. Compared to other Latin America countries, Uruguay reported a significant number of cases with an unknown serogroup, especially during the period 2017–202191.

Our results showed that MenW was associated with non-meningeal manifestations in the elderly, although we also noticed this association in individuals aged 19–59 years. Pneumonia occurred most frequently in adults aged over 60 years as reported in the literature13,23,33,40,63.

Changes in the antimicrobial susceptibility of capsular groups were seen as variations in intermediate resistance to penicillin, which on average was 56.7%, mainly associated with MenB that presented 65% intermediate resistance. These rates are similar to those previously reported for MenB, 64.1% between 1998 and 200820, 68.5% in 201086 and 74% between 2006 and 201320,31. In line with our results, reduced susceptibility to penicillin was frequently observed worldwide, which in in most cases was generated by horizontal DNA exchanges between meningococci and commensal Neisseria species21.

High-level resistance to penicillin was not detected in Argentina. Isolates with high-level resistance to penicillin (MIC>2mg/l) due to ROB-1-type β-lactamase production are extremely rare, but have been sporadically detected in Canada, France, the UK, Germany, Sweden and Mexico54,74,89. Some β-lactamase positive and quinolone-resistant MenY isolates were recently reported in the USA and El Salvador belonging to ST-3587 ST-23 cc54,57. This clonal complex has not been detected in Argentina to date. In our study, all N. meningitidis isolates remained susceptible to third-generation cephalosporins; however, it is important to point out that invasive isolates with reduced susceptibility to these antimicrobial agents associated with mutations in the penA gene have been identified in France21.

In this study, a great diversity of penA alleles was found and no association between reduced susceptibility to penicillin and specific penA alleles was observed as reported by other authors61.

Resistance to ciprofloxacin has been reported in several countries, mainly due to alterations in the gyrA gene encoding DNA gyrase subunit A. In our study, five isolates were ciprofloxacin-resistant and harbored mutations in the QRDR region of gyrA (Thr-91-Ile, Val-91-Ile and Asp-95-Ile), which have been associated with conferring ciprofloxacin resistance in meningococcal isolates worldwide. Two of the three amino acid substitutions have been previously reported in Argentina, where quinolone resistance is very low since it was first detected in 200219,86.

A strong association was found between capsular groups and clonal complexes. All MenW isolates belonged to ST-11 cc, a hypervirulent clone that has been associated with high levels of morbidity and mortality3. In Argentina, the number of IMD cases caused by this serogroup began to increase in 2007, reached a peak in 2012 and decreased towards 201531,63. The analysis of the hypervirulent clone ST-11 belonging to MenW is important to identify changes and diversification into new lineages over time, as has occurred in other countries around the world. Whole genome sequencing studies have shown that there are two different lineages of the MenW ST-11 cc: 11.1 and 11.2. Lineage 11.1 is divided into two sublineages: the Anglo-French Hajj strain and the South American/UK strain. The first sublineage comprises strains relating to the Hajj outbreak from 2000 onwards, represented by the endemic MenW:cc11 from South Africa that emerged in 2003 (South African Strain) and the epidemic MenW:cc11 from sub-Saharan Africa (Burkina Faso/North African Strain). The second sublineage includes the endemic clusters of MenW:cc11 from South America that have caused an increase in IMD cases in Brazil (2003), Argentina (2007), Chile (2012) and also in England and Wales (2009)52.

A novel lineage that emerged from the South American/UK strain, the UK strain 2013, caused an outbreak in Japan associated with the 23rd World Scout Jamboree and later spread to Scotland and Sweden32,53. In 2016, in Brazil, a new MenW:cc11 South America sublineage variant was detected, the Brazil strain 2016, carrying a novel fHbp peptide 124150.

The structure of the MenW population in Argentina has remained stable over the years. All MenW isolates from the period 2015–2022 belonged to ST-11 cc and 85.8% exhibited P1.5-2, fHbp 2.22, NHBA 29 and NadA 6. The fHbp 1241 variant, which became predominant in Brazil, has not been detected in Argentina. However, we observed a predominance of FetA 1-1 and PorB 2-144 associated with ST-11 cc, as described in Brazil50. The presence of NadA 6 in 97.5% of MenW isolates could indicate potential cross-reactivity of these strains with the Bexsero vaccine, as shown in a previous study in Argentina28. In the United Kingdom, real-world evidence of the use of Bexsero in the NIP demonstrated a 69% reduction of MenW cases, indicating the likelihood of this vaccine to protect against non-MenB IMD8,49.

The distribution of ccs within MenC showed predominance of singletons, followed by ST-11 cc and ST-41/44 cc. Singletons were mainly represented by ST-2196, which is endemic to Chaco province (NW). This sequence type is rare in the rest of the world, only 8 isolates have been described in Europe between 2000 and 2011, and none were associated with serogroup C: 3 in the UK isolated from carriage associated with NG and cnl, 2 in Spain belonging to MenB invasive disease strains (not specified), 1 in the Netherlands associated with MenY invasive disease (not specified) and 2 from Portugal in MenW strains causing septicemia47. Most of these isolates exhibit P1.21.4 and FetA VR 1-5, similar to those from Argentina. Genomic data is available for 4 of the European isolates. All of them contain NHBA 53, just as the Argentine strains, and fHbp peptide 119, unlike the local isolates that contain fHbp peptide 1947.

Three ccs were exclusively associated with MenY, the most frequent was ST-167 cc followed by ST-23 cc and ST-174 cc. As for ST-175 cc, it was found in MenY and in two isolates in which the capsular group could not be defined. In a previous study in Argentina, the association of ST-167 cc and ST-23 cc with MenY was also observed71. Similar results were found in other Latin American countries, such as Colombia (Moreno et al., 2020) and in Europe, where the main ccs associated with MenY were ST-23 cc and ST-167 cc12,44. The protein structure of ST-167 cc, regarding porA, P.1,5-1,10-4, was homogeneous and similar to that found in other studies44.

MenB showed wide genetic diversity. The most common cc associated with this capsular group was ST-865 cc (22.2%), followed by ST-35 cc, ST-41/44 cc, ST-32 cc and less frequently, ST-162 cc, ST-461 cc, ST- 60 cc, ST-213 cc, ST-103 cc and ST-269 cc. In Latin America, the specific population structure of MenB differs among countries in the region. In Brazil, the main ccs associated with MenB were ST-461 cc, ST-35 cc, ST-32 cc, and ST-213 cc51. In Colombia, the singleton ST-9493 predominated, followed by ST-32 cc, ST-35 cc and ST-41/44 cc61. In Chile, ST-41/44 cc and ST32 cc prevailed, and less frequently ST-213 cc and ST-162 cc77.

In Southern European countries, the main ccs associated with MenB were ST −41/44 cc, ST-162 cc, ST-32 cc, ST-269 and ST-213, representing 65% of IMD isolates94.

In North America, ccs were similar to the ones found in Europe. In Canada, most common ccs associated with MenB were ST-269 cc, ST-41/44 cc, ST-213 cc, ST-32 cc and ST-35 cc in order of frequency; in the US, the two predominant ccs were ST-41/44 cc and ST-32 cc4,82.

The ccs associated with MenB in our study are the same ones that cause invasive disease in Latin America and the rest of the world, and the distribution appears to remain constant over the years29,86. However, the predominance of ST-865 cc is unique to Argentina and the reason is still unknown. ST-865 cc associated with MenB was also found in isolates from carriage studies in the country38. In Chile, ST-865 cc was detected in a low proportion of carriage isolates but not as a cause of IMD81.

There are few reports of invasive ST-865 cc isolates elsewhere in the world. Based on the data available in the PubMLST database, ST-865 cc includes isolates from ST-865 and ST-3327 associated with MenB and ST-7180 associated with MenC. ST-865 and ST-7180 invasive isolates appear to be restricted to South Africa, where a molecular characterization study of MenB in a particular region of this country reported that ST-865 cc accounted for only 4% of IMD cases59. In the Czech Republic, invasive isolates of ST-865 cc associated with MenW belonged to a local sequence type ST-334243.

ST-3327 represented the main sequence type of ST-865 cc in Argentina, few isolates from this sequence-type are found in the PubMLST database. Most ST-3327 isolates from European countries carry the same PorA P1.21,16-36 and fetA F5-8 as those from Argentina, but account for a low proportion of invasive MenB isolates in these countries1. Conversely, in Argentina, ST-3327 causes a significant proportion of cases and is restricted to MenB isolates. Some singletons in our study correspond to SLVs of this predominant sequence type. The identification of ST-865 cc as a predominant MenB clonal complex is specific to Argentina in South America, and the factors contributing to its prevalence in our country remain unknown.

To evaluate the potential coverage of the Bexsero® and Trumenba® vaccines we used the MenDeVAR index to assess the presence and possible immunological cross-reactivity of different vaccine antigen variants78. In our study, the overall Bexsero® coverage estimate was low 19.3. Exact match was mainly due to ST-41/44 cc presenting NHBA peptide 2 and ST-162 cc that harbored PorA VR2-4. Cross reactivity was observed in the isolates belonging to various different alleles and ccs, among which no major associations were found. One of the main findings of this study was the large proportion of MenB strains categorized as “insufficient data”, thus limiting a reliable prediction of potential coverage provided by the MenB vaccines with the MenDeVar index. Results from a previous study in Argentina assessing the coverage of Bexsero® through hSBA in MenB isolates from the period 2010-2014, showed a vaccine coverage of 78.4% in adolescents and 51.4% or 64.9% in infants depending on the threshold considered. Taking into account that the distribution and antigenic composition of ccs within the MenB isolates are currently similar to those of isolates from the 2010–2014 period, we could assume that the potential real coverage of Bexsero® is higher than that depicted by the MenDeVAR index. Additionally, the potential coverage by MenDeVAR is also probably underestimated due to the high proportion of MenB strains with insufficient data, as previously mentioned.

The estimated coverage of Trumenba® was 40%, the ccs that contributed the most were ST-35 cc, which harbored fHbp allele 16, ST-41/44 cc due to fHbp allele 19, and ST-461 cc, which contained fHbp allele 47.

Based on published data, MenDeVAR is a pragmatic tool that can be used to decide the best vaccine strategy to apply in the event of a MenB outbreak. However, it has limitations since it is based on information that results from combining WGS data and published data from in vitro tests (MATS, MEASURE and human Serum Bactericidal Assay) that are not the most appropriate correlates of protection. Furthermore, the expression of several antigens cannot be inferred by WGS. On the other hand, this tool is used only to estimate direct protection since it cannot be applied to assess herd immunity78.

A limitation of this study is that the data corresponded to laboratory surveillance; therefore, the results of relative frequencies must be integrated into national surveillance data before drawing conclusions on incidence rates.

The inability to perform standard WGS on non-viable isolates hinders the extent of strain characterization for a proportion of IMD cases in Argentina.

Strengths and conclusionsWe believe that our role as NRL is important to detect fluctuations in circulating capsular groups and changes in the prevalence and structure of clones. Indeed, laboratory surveillance through WGS is an essential tool to detect variations in the constitution of Men B protein antigens that could potentially change vaccine coverage.

Integrating laboratory information to public health data could significantly enhance the national surveillance of IMD. More studies are needed to compare invasive and carriage isolates, including comprehensive clinical data to help strengthen our understanding of N. meningitidis virulence and transmission.

This study provides data that contributes to helping local national health authorities in making evidence-based decisions for the prevention of IMD, namely incorporating and updating meningococcal vaccines in the NIP, particularly considering the sustained increase in MenB cases since 2015 and the fact that Bexsero is only administered to high-risk groups.

FundingThis work was supported by the regular federal budget of the National Ministry of Health of Argentina. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Gustavo Ayala for technical support.

Hospital de Pediatría “Dr. Juan P. Garrahan”-Claudia Hernández, Alejandra Blanco, Vanessa Reitjman; Hospital General de Agudos “Donación Francisco Santojanni”-Claudia Alfonso; “Sanatorio Franchin”-Claudia Etcheves; “Sanatorio Trinidad Palermo”-Débora Stepanik; “Hospital Italiano”-Graciela Greco, María Ángeles Visus; “Hospital de Niños “Dr. Ricardo Gutiérrez”-Marisa Turco, Adriana Procopio, Miryam Vázquez; “CEMIC”-Mariela Soledad Zarate; “Hospital Británico”-Marta Giovanakis; “Hospital de Niños” “Pedro de Elizalde”-Rosana Pereda; “Sanatorio Guemes”-Soledad Zarate; “HIGA Evita”-Ana Togneri; HIGA “Dr. José Penna”-María L. Benvenutti, Mabel Rizzo; HIGA “Dr. Abraham F. Piñeyro” Monica Machain; “HIGA Luisa C. de Gandulfo”-Andrea Fascente; “Hospital Municipal de Agudos” “Dr. Leónidas Lucero”-Laura Paniccia; “HIGA” “Presidente Perón”-María Adelaida Rosetti; HIGA “Vicente López y Planes”-Hebe Gullo, María Susana Commisso; Hospital Zonal General de Agudos “Dr. Carlos Bocalandro”-Carolina Baccino, Nory Cerda; Hospital Materno Infantil “Dr. Victorio Tetamanti”-Victoria Monzani, Laura Morvay; Hospital Municipal “Dr. Bernardo Houssay”-Micaela Sogga; Hospital Universitario Austral-Viviana Vilches; Hospital de Niños “Sor María Ludovica”-Cecilia Vescina; Hospital Municipal de Pediatría “Dr. Federico Abete”-Liliana Esteves; Hospital del Niño de San Justo-Johanna Perez, Liliana Meccia; HIGA “Eva Perón”-Marisa Almuzara; Hospital Municipal “Ramón Santamarina”-Monica Sparo; Hospital Municipal “Dr. Federico Falcon”-Gabriela Galán; Hospital Municipal “Ostaciana V. Lavignolle”-Roxana Depardo; “HIGA Simplemente Evita”-Maricel Garrone; Hospital Nacional “Prof. Dr. Alejandro Posadas”-Adriana Fernández Lausi, Graciela Priore; Hospital Privado de Comunidad-Monica Vallejo; Hospital Zonal General de Agudos “Virgen del Carmen”-Adriana Melo; Hospital Municipal “Dr. Pedro Orellana”-Cecilia Barrachia; Hospital Zonal General de Agudos “Virgen del Carmen”-Adriana Melo; Hospital “Dr. Lucio Molas”-Gladys Almada; Hospital “Gobernador Centeno”-Adriana Pereyra; Laboratorio Central de Salud Publica Catamarca-Daniela Carrizo; Hospital Interzonal de Niños “Eva Perón”-Patricia Valdez, Mariela Silvia Farfan; Hospital Pediátrico “Dr. Avelino Castelán” Chaco-Leyla Guadalupe Gómez Capara; Mónica Graciela Sucin, Viviana Isabel Saito; Hospital 4 de Junio “Dr. Ramón Carrillo”-Norma Ester Cech; Hospital “Dr. Julio C. Perrando” Laura Picoli, Mariana Carol Rey, Isabel Ana Marques; Hospital Regional “Dr. Victor M. Sanguinetti-Chubut-Susana Ortiz; Laboratorio de la dirección de patología prevalente y epidemiología-Mario Flores; Red de Laboratorios-Diana Berry; Hospital Zonal de Trelew-Teresa M. Strella; Hospital Zonal de Esquel-Omar Daher; Hospital “Dr. Guillermo Rawson” Córdoba-Ana Littvik; Hospital Regional “Dr. Louis Pasteur”-Claudia Amareto de Costabella; Clínica Privada Vélez Sársfield-Lidia Wolff de Jakob; Hospital Regional “Domingo Funes”-Lilia Norma Camisassa; Clínica Universitaria “Reina Fabiola”-Marina Botiglieri; Hospital Infantil Municipal Córdoba-Liliana González; Hospital de Niños “Santísima Trinidad”-Patricia Montanaro; Hospital Pediátrico Del Niño Jesús-Paulo Cortez; Hospital “Ángela Llano”-Ana María Pato; Hospital Pediátrico “Juan Pablo II”-Adriana Wolfel; Hospital Materno Infantil “San Roque” Entre Ríos-Lorena del Barco, Maria Silvia Diaz, Maria Eugenia de Torres; Hospital “Delicia C. Masvernat”-María Ofelia Moulins, Luis Otaegui, Norma Yoya; Hospital “Dr. Lucio Molas”-Gladys Almada; Hospital “Gobernador Centeno”-Adriana Pereyra; Hospital de la Madre y el Niño-Nancy Comello, Silvana Vivaldo; Hospital Central-Nancy Noemí Pereyra; Hospital Regional “Dr. Enrique Vera Barros”-La Rioja-Sonia Flores, Mónica Romanazi; Hospital de Niños “Dr. Héctor Quintana”-Marcelo Toffoli, Gabriela Granados; Laboratorio Central de Salud Pública-Beatriz Resina; Hospital Pediátrico “Dr. Humberto Notti”-Laura Balbi, Alfredo Matile, Beatriz García; Hospital “Dr. Teodoro J. Schestakow”-Ada Zanusso, Adriana Edith Acosta; Hospital Provincial de Pediatría “Dr. Fernando Barreyro” Misiones-Martha Von Spetch, Sandra Grenon, Lorena Leguizamón; Hospital Escuela de Agudos “Dr. Ramón Madariaga”-Viviana Villalba; Hospital Provincial “Dr. Castro Rendón” Neuquén-Cristina Pérez; Red de Laboratorios-Evelin Oller; Hospital “Dr. Horacio Heller”-Fernanda Bulgueroni; Hospital Zonal Bariloche “Dr. Ramón Carrillo” Rio Negro-Néstor Blázquez, María Laura Álvarez; Hospital Área Cipolletti-Cristina Carranza, Mariela Roncallo; Hospital “Francisco López Lima”-Gonzalo Crombas, Daniela Durani; Hospital “A. Zatti”-Graciela Stafforini, María Gabriela Rivolier; Hospital “Presidente Perón” Salta-Cristina Bono, Eloisa Aguirre; Hospital Público Materno Infantil-Ana Berejnoi; Programa Bioquímica de Salta-Jorgelina Mulki; Hospital “San Vicente de Paul”-Silvia Amador; Hospital del Milagro-Norma Sponton; Hospital “Dr. Guillermo Rawson” San Juan-Marisa López; Hospital “Marcial Quiroga”-Hugo Castro; Policlínico Regional “Juan Domingo Perón”-“San Luis”-Ema María Fernández; Hospital Privado San Luis-Hugo Rigo; Hospital Zonal de Caleta Olivia “Pedro Tardivo” Santa Cruz-Josefina Villegas; Hospital Regional de Rio Gallegos-Mariel Borda, Alejandra Vargas, Wilma Krause; Hospital de Niños “Dr. Víctor J. Vilela” Santa Fe-Andrea Badano, Adriana Ernst, Mariel Borges; Laboratorio Central de Salud Pública-Andrea Nepote, María Gilli; “CEMAR”-María Inés Zamboni, Julieta Valles; Hospital “Dr. José M. Cullen”-Emilce Méndez, Alicia Nagel; Hospital Español-Santa Fe-Noemí Borda; Hospital de Niños “Dr. Orlando Alassia”-Stella Virgolini, María Rosa Baroni; Hospital Regional “Dr. Ramón Carrillo”-Marciana Cragnolino Santiago del Estero; Hospital de Niños (CePSI) “Eva Perón”-María Elisa Pavón; Hospital Regional Ushuaia-Manuel Boutureira; Hospital Regional Río Grande-Marcela Vargas, Alejandra Guerra; Hospital del Niño Jesús-Tucumán-Ana María Villagra De Trejo, José Assa; Hospital de Clínicas “Presidente Dr. Nicolás Avellaneda”-María Fernández de Gandur; Laboratorio de Salud Pública-Norma Cudmani; “Instituto Argentino de Diagnostico y Tratamiento”-Gabriela Boscaro; “Sanatorio Sagrado Corazón”-Julián Fazio; “Instituto Alexander Feliming”-M. Blanchery; “Htal. Zonal Materno Infantil Argentina Diego”-Stella Maris Altamiranda; “Htal. Juan A. Fernández”-Liliana Guelfand; “Htal. Dr. Arturo Oñativia” Ana Laura Mariñansky; “Htal. Larcade”-Rech Sabrina; “Htal. Narciso López”, Lanús-Jimena Zandonadi; “Htal. E. Tornú”-Liliana Longo; “Htal. San Juan de Dios -La Plata”-Andrea S. Pacha; “Hospital Municipal de Tigre”-Tolini Maria Cecilia; “Htal.” “Blas l. Dubarry”-Ana Gómez; “Htal. Español, CABA”-Scolnik; “Hospital Nuestra Señora de Luján”-Araceli Burella; “Hospital Emilio Zerboni”-Sofia Murzicato; “Clínica del Niño y la Familia, Quilmes”-Martínez Coleman Verónica,Galiñanes Sebastián; “Hospital San José”-Zanotto M. Cecilia; “Clínica Constituyentes”-Rosaura Taboada; “Hospital Dr. T Álvarez, CABA”-Liliana Rodriguez; “Fundación Hospitalaria”-Alejandra Lasont; “Instituto Modelo de Cardiología SRL, Córdoba”-María Soledad Muñoz; “Htal. Iturraspe, Santa Fe”-Maneiro Guillermina; “Htal. Militar Central Cirujano Mayor Cosme Argerich”-Nora Gómez, Tte. Coronel Perret Sonia; Htal de Clinicas “Jose de San Martin”-Carlos Vay; Hospital General de Agudos “Dr. Ignacio Pirovano”-Claudia Garbaz; Hospital General de Agudos“Dr. Parmenio Piñero”-Daniela Ballester, Flavia Amalfa; Hospital Alemán-Liliana Fernandez Caniggia; Hospital General de Agudos “Dr. Carlos.G. Durand”-Marta Flaibani; FLENI-Nora Orellana; Hospital General de Agudos “Dalmacio Vélez Sarsfield”-Silvana Manganello; Hospital “Churruca -Visca”-Iliana Martinez; HIGA “Dr. Pedro Fiorito” Silvia Beatriz Fernández; HIGA “Dr. Diego Paroissien”-Maria R Cervelli, Hospital Zonal Especializado de Agudos y Crónicos “Dr. A. Cetrangolo”-Appendino Andrea, Laura Biglieri; Hospital Zonal “Gdor. Domingo” “Mercante”-Sandra Bognanni; Hospital Municipal “Dr. Enrique Sturiz”-Alejandra Sale; Hospital Interzonal General de Agudos “Dr. Enrique Erril”-Victoria Ascua.