Clostridioides difficile is an etiological agent of diarrhea, and the use of antibiotics is one of the main risk factors for infection. Antimicrobials used for treatment are vancomycin (VAN), metronidazole (MET), and fidaxomicin. Resistant strains have been detected, exhibiting regional and institutional differences. The aim of this work was to determine the susceptibility profile of C. difficile clinical isolates to 14 antimicrobials, and to compare resistance among participating centers. A total of 208 consecutive isolates recovered from seven Argentinian hospitals between January 2018 and March 2020 were studied. MIC was determined by the agar dilution method (CLSI-M100 29ED). Azithromycin (AZM), clindamycin (CLI), ertapenem (ETP), imipenem (IMI), levofloxacin (LEV), linezolid (LNZ), meropenem (MER), metronidazole (MET), moxifloxacin (MOX), piperacillin–tazobactam (PTZ), rifaximin (RFX), teicoplanin (TEI), tigecycline (TGC), and VAN, were tested. The results were analyzed with SPSS 21.0. Chi-square was used to compare data, and statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Susceptibility percentages were as follows: VAN, TEI, and MET, 100%; TGC, 97.6%; PTZ, 96.2%; LNZ, 95.2%; MER, 99.5%; ETP, 60.9%; IMI, 42.8%; RFX, 55.6%; LEV, 48.6%; MOX, 46.1%; CLI, 29.9%; and azithromycin, 17.8%. Significant differences in resistance among centers were observed for: RFX (16.7%–91.7%), CLI (41.2%–86.1%), MOX (22.9%–97.2%), IMI (0%–55.6%), and azithromycin (62.5%–97.2%). Multidrug resistance (MDR) was detected in 80 isolates (38.5%), of which 63 (78.7%) were resistant to three families of antimicrobial agents and 17 (21.3%) were resistant to four. The most frequent combinations were RFX–MOX–CLI, present in 48 (60.0%) isolates, and RFX–IMI–MOX–CLI in 17 (21.3%) isolates. VAN, TEI, and MET were the most active antimicrobials in vitro against C. difficile strains. MER was the most active carbapenem, whereas IMI was the least active. We highlight the differences across institutions that could reflect epidemiological characteristics, and/or the dissemination of clones in each institution.

Clostridioides difficile causa diarreas, y el uso de antibióticos es uno de los principales factores de riesgo. Los tratamientos se realizan con vancomicina (VAN), metronidazol (MET) y fidaxomicina. Se detectaron cepas resistentes con diferencias regionales e institucionales. Los objetivos de este trabajo fueron determinar la sensibilidad de aislados clínicos de C. difficile frente a 14 antimicrobianos y comparar la resistencia entre centros. Se estudiaron 208 aislados consecutivos de 7 hospitales argentinos entre enero de 2018 y marzo de 2020. Se determinó la CIM por dilución en agar (CLSI-M100 29ED) de azitromicina (AZM), clindamicina (CLI), ertapenem (ETP), imipenem (IMI), levofloxacina (LEV), linezolid (LNZ), meropenem (MER), MET, moxifloxacina (MOX), piperacilina-tazobactam (PTZ), rifaximina (RFX), teicoplanina (TEI), tigeciclina (TGC) y VAN. Se utilizó chi-cuadrado para comparar los datos y se asignó significación estadística a p<0,05 (SPSS21.0). Los porcentajes de sensibilidad fueron: VAN, TEI y MET, 100%; TGC, 97,6%; PTZ, 96,2%; LNZ, 95,2%; MER, 99,5%; ETP, 60,9%; IMI, 42,8%; RFX, 55,6%; LEV, 48,6%; MOX, 46,1%; CLI, 29,9%, y AZM, 17,8%. Entre centros, se encontraron diferencias significativas en la resistencia: RFX (16,7%-91,7%), CLI (41,2%-86,1%), MOX (22,9-97,2%), IMI (0-55,6%) y AZM (62,5-97,2%). Se detectó multirresistencia en 80 (38,5%) aislados. VAN, TEI y MET fueron los antimicrobianos más activos frente a C. difficile. MER fue el carbapenem más activo e IMI el menos activo. Destacamos las diferencias entre instituciones, que podrían reflejar características epidemiológicas o de diseminación clonal en cada institución.

Clostridioides difficile is a toxigenic Gram-positive rod, spore-forming anaerobe that causes intestinal diseases. C. difficile infection (CDI) is mediated by the production of two toxins: an enterotoxin (toxin A), encoded by the tcdA gene, and a cytotoxin (toxin B) encoded by the tcdB gene. Some strains can produce a third unrelated binary toxin, which is encoded by the cdtA-cdtB genes and has no clearly defined role in humans.

C. difficile is a leading cause of diarrhea in hospitalized patients worldwide. It is the etiological agent of 25–30% of hospital-acquired diarrhea; however, CDI also occurs in community patients.

C. difficile causes 15–25% of episodes of diarrhea associated with antibiotic treatment. Exposure to antimicrobials plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of CDI. Antibiotics produce disruption of the gut microbiota and create an environment susceptible to C. difficile colonization and subsequent CDI4. This event is favored by the high level of antibiotic resistance detected in C. difficile clinical isolates41.

Antibiotic administration is the most common risk factor for CDI49; consequently, almost all antimicrobial agents have been associated with the development of CDI. However, agents such as amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, CLI, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones pose a higher potential risk2,4,8,45. Other important risk factors are hospitalization, residence in chronic care institutions, and environmental colonization4,8,45.

Clinical manifestations range from mild diarrhea to life-threatening toxic megacolon and pseudomembranous colitis, sepsis and death45,49. Additionally, up to 20% of patients with CDI with a favourable outcome experience a recurrent episode within four weeks of completing the treatment. Among them, the risk of a third episode rises to 60%.

The antibiotics used for the treatment of CDI are vancomycin (VAN), metronidazole (MET), and fidaxomicin25,41,46; nevertheless, the latter is not available in all countries. Thus, in Argentina, MET and VAN are the most prescribed agents for the treatment of this infection4. Teicoplanin (TEI), tigecycline (TGC), and nitazoxanide are alternative drugs, and in the absence of response to treatment or recurrences, linezolid (LNZ) or rifaximin (RXM) could be added4,5. However, the emergence of antibiotic resistance and multidrug resistance has been reported; therefore, periodic monitoring is vital for appropriate therapy13. Due to regional and institutional variations49, knowledge of the resistance profiles of locally circulating C. difficile strains is crucial. In Argentina few antibiotic susceptibility studies involving human clinical isolates of C. difficile have been conducted28,30,38.

The present study aimed to determine antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of 208 C. difficile strains isolated from patients with CDI against 14 antibiotics and to compare resistance across the participating centers.

Materials and methodsBacterial isolatesA total of 208 consecutive isolates of C. difficile were studied. They were obtained from seven hospital centers from the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires, Argentina, six from Buenos Aires City (CE, HA, HC, HG, HM, IL), and one from Buenos Aires Province (HP), and were collected between January 2018 and March 2020. The distribution of isolates across the participating centers was as follows: CE 32, HA 33, HC 31, HG 35, HM 36, HP 36, IL 5.

They were isolated from stool samples of patients with diarrhea and a diagnosis of CDI. The diagnosis was performed according to a two-step algorithm4. In all cases, GDH and toxins were detected using a membrane enzyme immunoassay kit (C. Diff Quik Chek Complete™, TECHLAB), and toxigenic cultures were used for the second step when necessary.

Then, in order to obtain the isolates for this study, a toxigenic culture was done on all samples that resulted positive. Following alcohol shock-based selection of spores, isolation of C. difficile was performed. Equal parts of feces and 98% ethanol were mixed, vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 20min. Afterwards, 10μl of the mix was poured onto blood agar plates, which were incubated in jars under anaerobic conditions at 35°C for 48–72h. Suspicious colonies were identified by their characteristic colony morphology, Gram stain, biochemical tests, and mass spectrometry systems such as MALDI-TOF MS, BD Bruker Biotyper™ (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) or Vitek™ MS (bioMérieux, Marcy-L’Etoile, France), when necessary. Toxin production was detected using the C. Diff Quik Chek Complete™ kit, TECHLAB.

The strains were stored at −20°C in brain heart infusion broth plus 15% glycerol. To recover the isolates, two subcultures were performed onto blood agar plates, and incubated under anaerobic conditions at 35°C for 48h.

All the isolates were subsequently sent to the research laboratory at the Facultad de Medicina of the Fundación Barceló, where antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testsMinimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by agar dilution method according to CLSI-M100 29th edition9. Tests were performed on Brucella agar supplemented with haemin (5μg/ml), vitamin K1 (1μg/ml), and laked horse blood (5% v/v).

The antibiotics tested were of certified potency, and their respective concentration ranges in μg/ml were: azithromycin (AZM), 0.12–128; clindamycin (CLI), 0.12–64; ertapenem (ETP), 0.12–64; imipenem (IMI), 0.12–64; levofloxacin (LEV), 0.12–128; LNZ, 0.03–16; meropenem (MER), 0.12–64; MTZ, 0.12–128; moxifloxacin (MOX), 0.12–64; piperacillin–tazobactam (PTZ), 0.25–512; RFX, 0.002–128; TEI, 0.008–16; TGC 0.06–4, and VAN, 0.03–16.

MICs were recorded after 48h of incubation and values were interpreted according to CLSI-M100 33rd edition10. For those agents whose breakpoints were not defined by CLSI, EUCAST or published data15,16,37,49 were adopted.

Breakpoints for MTZ, CLI, IMI, MER, ETP, MOX, and PTZ were those defined by CLSI-M100 33rd edition guidelines for anaerobic bacteria10. The breakpoints for VAN and TGC were defined according to EUCAST epidemiological cut-off (ECOFF) values for C. difficile15,16, for RFX resistant breakpoint was >32μg/ml37, for LEV, >8μg/ml49. The values for TEI, LNZ and AZM were >2μg/ml, >4μg/ml and >2μg/ml, respectively, and were adopted from those defined for Staphylococcus aureus15.

Quality control strains included C. difficile ATCC 700057, Bacteroides fragilis ATCC 25285, and Eggerthella lenta ATCC 43055. Plates for growth and aerotolerance controls were included.

Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as resistance to three or more families of antibiotics.

AZM and LEV were excluded from this analysis due to the lack of breakpoints for anaerobes. IMI and MOX were selected to represent carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, respectively.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using SPSS software, IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Antimicrobial resistances were compared across the participating centers. For this evaluation, just one agent per family was considered and strains from one of the centers (IL) were excluded because of the low number provided. The comparison was carried out using the chi-square test and statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

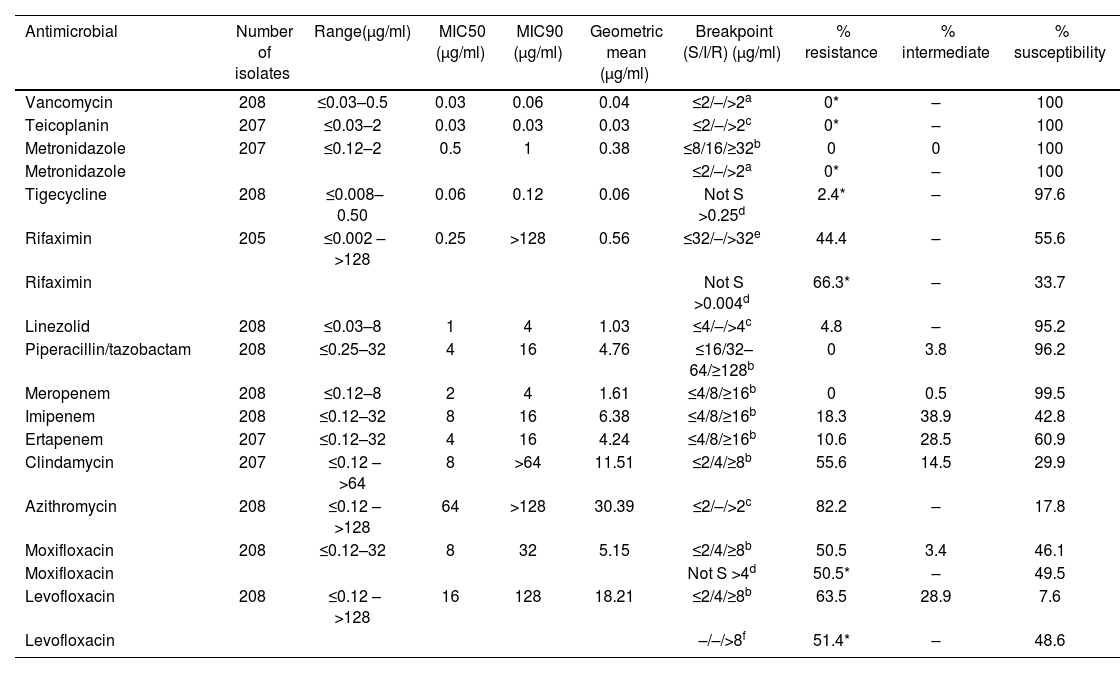

ResultsResults of ranges of MIC, MIC50, MIC90, geometric means, and percentages of susceptibility, intermediate, and resistance for each antibiotic tested are shown in Table 1. The distributions of the isolates according to the MIC values of each agent are presented in Figure 1.

In vitro activity of 14 antimicrobial agents against 208 isolates of Clostridioides difficile.

| Antimicrobial | Number of isolates | Range(μg/ml) | MIC50 (μg/ml) | MIC90 (μg/ml) | Geometric mean (μg/ml) | Breakpoint (S/I/R) (μg/ml) | % resistance | % intermediate | % susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | 208 | ≤0.03–0.5 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | ≤2/–/>2a | 0* | – | 100 |

| Teicoplanin | 207 | ≤0.03–2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ≤2/–/>2c | 0* | – | 100 |

| Metronidazole | 207 | ≤0.12–2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.38 | ≤8/16/≥32b | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Metronidazole | ≤2/–/>2a | 0* | – | 100 | |||||

| Tigecycline | 208 | ≤0.008–0.50 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.06 | Not S >0.25d | 2.4* | – | 97.6 |

| Rifaximin | 205 | ≤0.002 – >128 | 0.25 | >128 | 0.56 | ≤32/–/>32e | 44.4 | – | 55.6 |

| Rifaximin | Not S >0.004d | 66.3* | – | 33.7 | |||||

| Linezolid | 208 | ≤0.03–8 | 1 | 4 | 1.03 | ≤4/–/>4c | 4.8 | – | 95.2 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 208 | ≤0.25–32 | 4 | 16 | 4.76 | ≤16/32–64/≥128b | 0 | 3.8 | 96.2 |

| Meropenem | 208 | ≤0.12–8 | 2 | 4 | 1.61 | ≤4/8/≥16b | 0 | 0.5 | 99.5 |

| Imipenem | 208 | ≤0.12–32 | 8 | 16 | 6.38 | ≤4/8/≥16b | 18.3 | 38.9 | 42.8 |

| Ertapenem | 207 | ≤0.12–32 | 4 | 16 | 4.24 | ≤4/8/≥16b | 10.6 | 28.5 | 60.9 |

| Clindamycin | 207 | ≤0.12 – >64 | 8 | >64 | 11.51 | ≤2/4/≥8b | 55.6 | 14.5 | 29.9 |

| Azithromycin | 208 | ≤0.12 – >128 | 64 | >128 | 30.39 | ≤2/–/>2c | 82.2 | – | 17.8 |

| Moxifloxacin | 208 | ≤0.12–32 | 8 | 32 | 5.15 | ≤2/4/≥8b | 50.5 | 3.4 | 46.1 |

| Moxifloxacin | Not S >4d | 50.5* | – | 49.5 | |||||

| Levofloxacin | 208 | ≤0.12 – >128 | 16 | 128 | 18.21 | ≤2/4/≥8b | 63.5 | 28.9 | 7.6 |

| Levofloxacin | –/–/>8f | 51.4* | – | 48.6 |

Breakpoints were defined as susceptible, intermediately resistant or resistant with reference to CLSI, EUCAST or published data.

EUCAST, clinical breakpoint Tables v. 13.0, anaerobic bacteria, Clostridioides difficile valid from 2023-01-01.

CLSI, M100 Ed33, Table 2J – MIC breakpoint for anaerobes. 2023 (the breakpoint for moxifloxacin was used for levofloxacin).

EUCAST, clinical breakpoint Tables v. 9.0, Clostridioides difficile epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFF), 2019 (the ECOFF for rifampicin was used for rifaximin)9.

All isolates were susceptible to VAN and TEI (MIC ≤2μg/ml). Similar results were observed for MTZ according to both CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints (MIC ≤2μg/ml).

TIG was active against 97.6% of isolates, four isolates were non-susceptible with MICs of 0.5μg/ml for a breakpoint >0.25μg/ml. One hundred and fourteen (114) isolates (55.6%) were susceptible to RFX according to the breakpoints defined by Reigadas et al.37; however, 91 of them (44.4%) were classified as non-susceptible when using the EUCAST ECOFF value9.

LNZ was active against 95.2% of the isolates tested, 10 isolates with MICs of 8μg/ml were classified as resistant for a breakpoint >4μg/ml. Susceptibility to PTZ was observed in 96.2% of the isolates, and eight isolates, with MICs of 32μg/ml, were classified as intermediate.

MER was active against 99.5% of the isolates only one strain was classified as intermediate. Thirty-eight isolates were resistant to IMI, but none of them were resistant to ERT and MER.

Twenty-two isolates were resistant to ERT. Two of them were susceptible to IMI and 20 were intermediate. However, all 22 isolates were susceptible to MER. Seven isolates showed intermediate susceptibility to MOX according to CLSI guidelines, but were susceptible according to EUCAST breakpoints.

When comparing antibiotic resistance across centers, statistically significant differences (p<0.05) were found, mainly, for RFX, CLI, MOX, IMI, and AZM (Fig. 2).

RFX showed its characteristic bimodal behavior. Resistance ranged from 16.7% to 91.7% and was found mostly in two centers, HM and HP. The difference between these two institutions was 13.9% and was not significant; on the other hand, they were significantly different from the others.

For CLI, the range of resistance varied between 41.2% and 86.1%. The resistance rate of one center was significantly higher than the others.

MOX resistance ranged between 22.9% and 97.2%. HM and HP centers showed the highest values. Resistance in each of them differed significantly from the others.

Resistance to IMI varied from 9.4% to 55.6%. One center, with the highest resistance to IMI differed significantly from the others.

With regard to resistance to AZI, two groups presented statistically significant differences. In one group, CE and HG exhibited a resistance of 62.5% and 65.7%, respectively, whereas in the other group, HA, HC, HM, and HP showed values of 90.9%, 87.1%, 91.7%, and 97.2%, respectively.

MDR was detected in 80 isolates (38.5%), 63 (78.7%) were resistant to three families of antimicrobial agents, and 17 (21.3%) were resistant to four. The most frequent combinations were RFX–MOX–CLI, which was present in 48 (60.0%) isolates, and RFX–IMI–MOX–CLI in 17 (21.3%) isolates. Other resistant combinations were RFX–MOX–IMI in 10 isolates (12.5%), IMI–MOX–CLI in 3 (3.8%) and RFX–IMI–CLI in 2 (2.5%). The distribution of MDR per center is shown in Figure 3.

DiscussionCDI is a serious public health concern. C. difficile causes a variable spectrum of diseases, ranging from mild diarrhea to severe colon inflammation that can be life-threatening. Most patients develop diarrhea during or shortly after a course of antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic resistance rates vary considerably in different studies, probably depending on geographic regions and local or national antibiotic policy43. Several studies documented the increase in the antibiotic resistance of C. difficile due to the inappropriate use of broad-spectrum agents, including cephalosporins, CLI, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones, together with the emergence of hypervirulent strains13 such as C. difficile BI/NAP1/027, and other ribotypes that were also associated with antibiotic resistance.

The antimicrobials recommended for CDI treatment are VAN, MET, or fidaxomicin25,46. It was shown that fidaxomicin treatment reduces the recurrence rate. Nevertheless, treatment failures and recurrences were reported. In countries like Argentina where fidaxomicin is not marketed, oral VAN and MET remain the agents of choice4.

A systematic review of 39 studies found treatment failure in 22.4% and 14.2%, and a recurrence rate of 27.1% and 24.0% after treatment with MET and VAN, respectively47. Therefore, alternative treatments such as fidaxomicin, nitazoxanide, fusidic acid, TGC, TEI, and RXM were proposed6.

Appropriate antibiotic prescription is necessary to avoid the selection and spread of antibiotic-resistant C. difficile strains. Therefore, it is essential to conduct periodic antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance, with regional and institutional analyses to guide appropriate treatment in each area and institution. However, antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) is not routinely performed for C. difficile, and data evaluating MICs are limited, in particular from regions of Africa and South America13. In Argentina, there is still an insufficient number of reports regarding the susceptibility of circulating C. difficile strains. To date, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the largest survey published on the antimicrobial susceptibility of C. difficile conducted with isolates from human patients with CDI in Argentina.

Vancomycin–teicoplaninAll our isolates were susceptible to VAN and TEI.

Although CLSI does not publish susceptibility breakpoints for VAN, EUCAST clinical breakpoints define an epidemiological cut-off value for non-susceptible C. difficile strains. Thus, according to EUCAST, all our isolates could be considered susceptible, which is consistent with unpublished local data from isolates obtained from pediatric32 and adult patient28,38.

In 2016, while studying Brazilian isolates, Fraga et al.17 found MIC50 and MIC90 of 4μg/ml, with 58% of the isolates being non-susceptible. This important discrepancy compared with our results could be due to differences among the circulating strains, or to the use of the disk diffusion method for assessing antimicrobial susceptibility.

VAN was considered an agent with high and uniform in vitro activity, remaining stable over time14,20,41,43. However, a number of C. difficile strains with reduced susceptibility (MIC: >2, 4 and 8μg/ml) were detected in isolates from Taiwan, Iran, China, and Israel43.

On the other hand, in a systematic review and meta-analysis, Saha et al.40, reported a significant VAN resistance increased by 3.6% after 2012. However, this finding could be affected by the significant heterogeneity in the susceptibility testing methodology. The highest VAN resistance rate was observed in the Americas, followed by Asia, and was significantly high among the RT027 strains. Other RTs displaying reduced VAN susceptibility were, RT017, RT078, RT126, RT001/072, and RT35618,34. The authors did not detect resistance to TEI.

In addition, plasmid-mediated resistance to VAN was described in a C. difficile isolate from a patient with CDI nonresponsive to VAN treatment27.

Clinical significance of reduced VAN susceptibility remains to be determined, since after oral treatment, VAN achieves high concentrations in feces (1000–3000μg/ml), exceeding the highest MIC values recorded40,43.

Moreover, no VAN antimicrobial activity was detected on C. difficile spores, neither as a sporicidal nor as an inhibitor of sporulation, and the persistence of spores could contribute to the recurrence of CDI27. Furthermore, biofilm formation could be involved in VAN resistance34.

MetronidazoleResistance to MET remains rare but variable and dependent on the method and breakpoint considered11,17,40,43,44. It was reported to range from 0.11% to 18%11; however, resistant strains have not yet been recorded in Argentina28,30,32,38. A review and meta-analysis from Sholeh et al.41 described that when the EUCAST breakpoint was used, the highest MET-resistant rates were found in Asia (4.95%), followed by North America (3.95%) and Europe (1.95%). However, when the CLSI breakpoint was used, the highest resistance was observed in Europe (1.0%).

According to the CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints, 100% of our isolates were susceptible to this agent. Nine of them exhibited a MIC of 2μg/ml, which coincides with the EUCAST epidemiological susceptibility cut-off value. In the same way, in Sao Paulo, Fraga et al.17 did not find resistance among 50 isolates and reported MIC90 of 2μg/ml, one dilution higher than that found by us.

Gargis et al.21 reported 97.3% susceptibility to MET in the USA when considering the EUCAST cut-off value but found no resistance when using the CLSI breakpoint. MIC50 and MIC90 values coincided with ours. Likewise, in a systematic review and meta-analysis from Mainland China in 2016, no MET-resistant strains were found44.

In 2022, Costa et al.11 found that most isolates were susceptible to MET, but six isolates belonging to RT027 were resistant, whereas in 2018 Freeman et al.19 reported an increase in susceptibility to MET, possibly due to a reduction in the use of this drug, or strain diversity11.

An Israeli paper45 reported four (4.9%) isolates with reduced susceptibility, but using gradient strips methods and a breakpoint >2μg/ml.

Additionally, in an Iranian study by Baghani et al.3, it was reported that more than half of the toxigenic C. difficile isolates exhibited reduced susceptibility to MET, with 30 isolates demonstrating high resistance with a MIC >256μg/ml. The authors hypothesized that this high resistance could be linked to the overuse of MET. However, it is important to note that, unlike in our work, MICs were determined using test strips and interpreted according to EUCAST cut-off values.

MET resistance seems more common in non-toxigenic strains34. In Argentina, two isolates with an MIC of 16μg/ml were detected48, and as previously reported, these strains were non-toxigenic.

Peláez et al.35 documented that MET resistance is heterogeneous, inducible, and unstable after the freeze-thaw cycle. Although the true impact of heteroresistance is unknown, it could also influence treatment failure34,39.

Other factors such as iron concentration and resistant microbiota in the gut could also be related to MET resistance34. MET reaches low concentrations in the colon and feces, which may promote the development of resistance with impact on treatment failures34. In addition, as described for VAN, MET did not demonstrate significant inhibition of sporulation27. Furthermore, iron concentration, resistant microbiota in the gut, along with biofilm formation could influence the in vivo MET activity27,34, and explain cases of failure or recurrence associated to treatment with this drug.

TigecyclineA vast majority (97.6%) of the studied isolates was susceptible to TIG, but five (2.4%), coming from four different centers were classified as non-susceptible when applying the EUCAST epidemiological cut-off value16. A Brazilian study17 reported values similar to ours, with MIC90 of 0.12μg/ml and MIC higher than 0.25μg/ml in only one of 50 isolates. Likewise, in Europe a slightly reduced susceptibility to TGC was found; however, geometric mean MICs were more elevated in RT01220.

In an Israeli study, reduced susceptibility to TGC was found in 1.23% of isolates45; and the percentage of non-susceptible isolates was also low (1.6%) in a review and meta-analysis published in 202041.

Supported by its in vitro activity, TGC was proposed as a potential alternative treatment of severe CDI. It inhibits spore formation and decreases toxin production, but it reduces the healthy microbiota of the gut and thus may contribute to CDI recurrence34. Furthermore, recently, the emergence of mobile TGC resistance genes has raised concern about the possible decrease in the activity of this agent and the need for controlled clinical studies to evaluate its efficacy and potential use, especially in patients for whom the treatments of choice have failed and fidaxomicin is not available34.

RifaximinRFX is a rifamycin that has been used for intestinal decontamination and proposed as an adjunctive treatment to decrease recurrent CDI26,37. Our isolates showed a bimodal distribution (Fig. 1O), with more than 40% resistant ones and MIC90 >128μg/ml. Reigadas et al.37 also found this type of distribution with a high value of CIM90 >256μg/ml, a geometric mean of 0.25μg/ml, and 32.3% of resistance. Moreover, these authors demonstrated a good correlation between RFX results obtained by the agar dilution method and rifampicin results obtained by the E-test.

Lew et al.29 tested RFX activity on C. difficile isolated from twelve Asia-Pacific countries. They identified a global resistance level of 15.5%, which is lower than that observed in this study. However, this resistance occurred mainly in RT017, which represented 67.7%. Although ribotyping was not performed in our study, Goorhius et al.23 recognized the circulation of RT017 in C. difficile isolates in a hospital in Argentina between 2000 and 2005. Other authors have also shown evidence of its circulation in recent years12,31.

Rifamycins in long-term regimes are commonly used in the treatment of tuberculosis, and previous exposure to rifampicin has been reported to be a risk factor for rifamycin-resistant C. difficile34,43 strains. In the 2018 Freeman multicenter European study19, rifampicin resistance varied among the participating countries and was most notable in the Czech Republic (40.0–64.0%), Hungary (38.7–56.6%), Italy (36.6–47.0%), and Poland (5.0–44.0%). Later, the same authors20 published annual changes between 13.5% and 11.8%, and increased resistance in RTs 027, 198, 018, 356, 017, and 176. Similarly, Lew et al.29 found that RXM resistance varied across countries in the Asia-Pacific region and was absent in areas with low tuberculosis rates.

We also noted that the distribution of RXM resistance was heterogeneous across the participating centers. It varied between 16.7% and 91.7% and was highest in two of the seven centers (77.8% in HP and 91.7% in HM). In both, the number of patients with tuberculosis and, consequently, treated with rifampicin was greater than in the others. Rifampicin resistance in C. difficile isolates could be attributed to prior exposure to this agent with selection for resistant strains. However, transmission of rifampicin-resistant C. difficile strains to patients without a history of rifamycin use, could also occur34.

LinezolidAlthough C. difficile has been described as susceptible to LNZ, it has not been recommended for CDI treatment34. In this study, MIC varied between ≤0.03 and 8μg/ml, and when using the EUCAST clinical breakpoint for S. aureus16, 10 isolates (4.81%) were resistant. This percentage falls within the range of resistance found in Europe, which spreads from 1% to 5.7%34.

Piperacillin/tazobactamIn the current study, PTZ showed to be active against C. difficile. While 96% of the isolates were susceptible, none were resistant. Similarly, Saha et al. reported that C. difficile resistance was less than 1%40, and in 2022, a meta-analysis comprising 17 studies reported a WPR rate of 0%41.

CarbapenemsMER was the most active carbapenem studied, and similarly to other publications7,41 no resistant isolates were found. Then, ETP, which was active against 61% of the isolates, was 39% less active than MER, but more active than IMI. Information on the in vitro activity of carbapenems against C. difficile is scarce, and we did not find data on ETP activity; nonetheless, cases of ICD have been reported following treatment with this agent.

In our series, 18.27% of the isolates were resistant to IMI and only 42.79% were susceptible. However, the percentage of resistance was not uniform across the centers, finding a range of 46.20% (9.40–55.60%). European studies have shown variable percentages of resistance to IMI between countries, with values ranging from 0% in Belgium, Bulgaria and Sweden, to 76% in Hungary19,24,36. Furthermore, an Iranian publication22, using the disk diffusion method, recorded resistance in 81% of C. difficile isolates. In Europe, IMI resistance was primarily associated with RT01724,36. The differences observed among our centers may also be attributed to ribotype dissemination; however, molecular studies were not included in our actual aims. Additional factors such as the use of carbapenems, differences in population demographics, and clonal dissemination within each institution could also contribute to these differences.

ClindamycinCLI administration is a high-risk factor for the development of CDI, as its resistance is widespread among C. difficile strains, varying between 25% and 96%33. In this survey, less than a third of the isolates were susceptible, and the global resistance was 55.6%.

High-level resistance to CLI has already been detected in Argentina28,38. In addition, the presence of the ermB gene was evidenced in local RT017 isolates23.

Our current resistant rate aligns with findings from a Pan-European survey18 and two systematic reviews and meta-analysis13,41. The first reported a global resistance rate of 49.6%18 while the WPR values from the meta-analysis were 59%41 and 61%13, respectively.

On the other hand, our study found lower resistance rates to CLI compared with the 81.7% reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis from Mainland China44.

Sholeh et al.41 identified significant regional differences, with a higher prevalence of resistance in Asia (72.9%) and South America (59%). In this study, when comparing data across different centers, one of them exhibited a CLI resistance rate of 86.1%, a value significantly higher than those observed in the other hospitals, but more in line with those reported in Mainland China.

AzithromycinRegarding AZM, 82% of our isolates exhibited resistance. While AZM is not used for treating CDI, the resistance observed may clarify its potential to induce the disease. Similarly, a study conducted on elderly individuals residing in a nursing home in Iran reported a high AZM resistance rate of 61%, when the disk diffusion method was used22.

Moxifloxacin and levofloxacinFluoroquinolones are linked to an increased risk of CDI43,49, and resistance has been detected in 47% of C. difficile isolates43. Mutations in the GyrA and/or GyrB genes have been observed in these resistant strains21. Furthermore, MICs were found to be higher in isolates that contained the binary toxin11. However, in a study carried out in an Argentine pediatric hospital, resistance to fluoroquinolones was not associated to the binary toxin genes (personal communication from Dr. M. Litterio).

The rise in CDI associated with fluoroquinolones has coincided with an increasing incidence of C. difficile since the early 2000s19.

In this study, MOX was more active than LEV, and the difference was statistically significant (p=0.01). However, despite the differences, both fluoroquinolones are potential risks for CDI. Resistance to MOX remained consistent regardless of the cut-off point used, whereas resistance to LEV was significantly higher when following the CLSI breakpoint. Moreover, LEV resistance was notably higher than the 20.3% reported by Wang et al.49.

The global MOX resistance found in this study was much higher than the 8% detected in Brazil in 201617, and also surpassed the rates of 16%11 and 22.9%21 reported in the USA in 2022 and 2023, respectively. The resistance of our isolates was also higher than that of a Pan-European longitudinal surveillance, where MOX resistance was 39.9%. However, notable disparities were observed across countries, with a resistant range from 8% in France to 100% in Poland19. Moreover, a high resistance rate of 66% was found in Japan1.

The distribution of MOX resistance across our hospitals was heterogeneous; higher percentages were observed in two specific centers, HM and HP. These discrepancies were significant with respect to the other centers and also between each other. Figure 2 illustrates that the distribution of MOX-resistant strains mirrors that of RXM. These results suggest the presence of common factors in the institutions with the highest resistance levels. One potential factor could be the management of patients undergoing antituberculosis treatments, with the potential antibiotic selection pressure that this entails. Other factors may include clonal differences and the ribotypes present in these institutions.

Multidrug resistanceMDR is commonly observed among C. difficile strains, and generally involves resistance to CLI, erythromycin, fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and tetracyclines34,42. Our isolates showed 38.5% of MDR to the tested agents; however, erythromycin, cephalosporins and tetracyclines were not evaluated. Thus, MDR could be underestimated in our series. The most frequent resistant combinations were RFX–MOX–CLI, and RFX–MOX–CLI–IMI. MDR prevalence varies by geographical location and strain type. In the USA, RT027 strains were particularly associated with MDR, and showed co-resistance to CLI, MOX, rifamycins, and tetracyclines34. European data indicate a predominance of MDR in RTs 017, 027, and 198, with percentages ranging from 28% to 77%34. In particular, Italian MDR strains were linked to RT356 and RT018, both characterized by resistance to CLI, erythromycin, MOX, and RIF43. While in the Asia-Pacific region, it was observed in 100% of RT369, 92.7% of RT018, and 66.1% of RT01734. In China, MDR varied from 5.8% in the Southwest to 43.75% in South China34.

As expected, we also confirmed variations among institutions. In line with RXM and MOX resistance, MDR was significantly higher in the centers with the highest tuberculosis prevalence.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that VAN, TEI, and MET are the most active in vitro agents against C. difficile strains. Our results showed significant differences in resistance for CLI, IMI, MOX, AZM, and RFX across centers. In particular, we highlight differences for RFX and MOX, which could be associated to the use of antituberculosis drugs.

We consider that this work has the strength of being a multicenter study, and of including a significant number of consecutive isolates from humans with CDI. This is the first publication and the most up-to-date information on the in vitro susceptibility of C. difficile in Argentina.

FundingThe present work was supported by a grant awarded by IUCS-Fundación HA Barceló, Resolution No. 6973.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank Dr. Ana Pereyra for providing necessary supply for the preparation of culture media.