Organizations faced different development paths over the centuries, caused by changes in the competitive environment and the ability to respond to these changes. Such changes and choices can be analyzed from the perspective of innovation waves, responsible for changing the current competition structure and present a new competitive format for organizations. By observing the existing five waves of innovation, we can see a significant jump in development for companies that well understood the context of the new wave and competitive problems for other companies, even leaders in their market were “swept” off the competitive landscape. There are indications that a sixth wave of innovation is coming and who is guided by the sustainability, since the depletion of resources can cause many companies and countries conquer higher competitive performance to seek innovative solutions to the problem and those that fail to do so may have a loss of competitiveness. Given the aforementioned context, this theoretical essay aims to discuss sustainability as the sixth wave of innovation and how it can affect organizations. It is expected that the article raises a reflection about this phenomenon and serve as a starting point for future discussions.

The concept of innovation is directly related to the exploration of successful ideas that can generate profitable products, processes, services or profitable business practices (Schumpeter, 1982; Tether, 2003; Tidd, Bessant, & Pavitt, 2008). For an organization to innovate systematically – in other words, continuously; it should widen its field of vision not only in relation to the market but also in relation to itself (Crossan & Apaydin, 2010; Smith, Busi, Ball, & Van Der Meer, 2008; Tang, 1998). It should also maintain a systematic learning process that allows it to take advantage of new ideas. Companies that do this stand out because they manage to understand the dynamics of innovation in their markets, capturing and responding to changes and signals that arise from the environment (Utterback, 1996).

All products and companies are subject to waves of innovation, in other words, when a product changes significantly as compared to its previous version, leaping significantly ahead, usually driven by technological advances (Utterback, 1996). These discontinuities create the need for companies to seek innovations that enable competitive leaps (Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996) and require organizations to rethink their products and processes, as well as the impact of technology in their field of operation (Utterback, 1996).

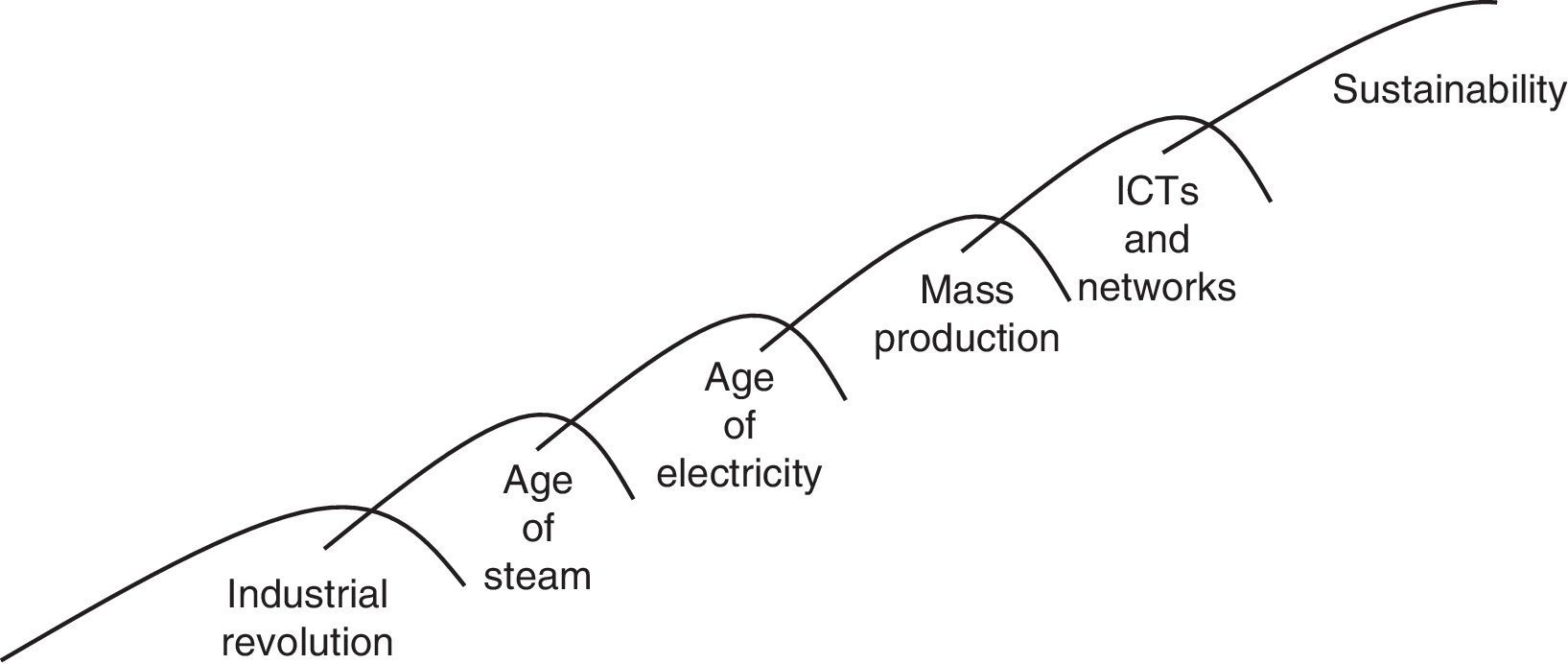

Throughout history five main waves of innovation, accompanied by technological and social changes, have been observed (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Seebode, Jeanrenaud, & Bessant, 2012). The first wave of innovation was the Industrial Revolution; the second, the Age of Steam; the third, the Age of Electricity; the fourth, the Age of Mass Production; and the fifth, the rise of Information and Communications Technology and Networks (Moody & Nogrady, 2010). There are signs of a new wave arising – that of Sustainability (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Seebode et al., 2012.).

The current debate revolves around the need for companies to incorporate sustainability as a competitive factor, linking it to organizational objectives and going beyond “mere” sustainable discourse in order to generate economic, social and environmental benefits that lead to the creation of competitive advantage and potential innovation (Barbieri, Vasconcelos, Andreassi, & Vasconcelos, 2010; Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Hart, 1997; Hart & Milstein, 2004; Kleindorfer, Singhal, & Wassenhove, 2005; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Nidumolu, Prahalad, & Rangaswami, 2009; Porter & Linde, 1995; Seebode et al., 2012).

Studies involving innovation and sustainability have attracted increasing attention in recent years, due to problems linked to the depletion of natural resources, pollution, traffic jams, nuclear risk, supply risk, energy and water shortages, sanitation, poverty, and disasters (Markard, Raven, & Truffer, 2012). Such problems provide opportunity for action and highlight the need for sustainable innovation systems, incentive policies and support for sustainability, as well as the development of technologies that enable organizations to combine economic, environmental and social objectives (Markard et al., 2012).

The development of new technology is one of the ways of addressing overcrowding in cities, pollution, traffic jams, an aging population and other social needs, and this can also lead to business opportunities. Thus, innovation has a leading role to play in this process, as it is innovation that enables the development of solutions for such problems (Han et al., 2012).

However, while society is demanding that companies take on an environmental and social role, and while this is seen as an opportunity for companies to develop and innovate, many of the innovation strategies that are adopted are inadequate to accommodate these demands (Hall & Vredenburg, 2012). Throughout history, when a new wave of innovation arises, market positioning changes, so that dominant companies are challenged and sometimes disappear, as they tend to defend their current practices and end up not responding adequately to change (Utterback, 1996).

All these issues make it necessary to discuss the possibility that the fifth wave of innovation is now giving way to Sustainability, since there is a strong social pressure for organizations to make their activities sustainable, as shown by the studies of Barbieri et al. (2010), Desha and Hargroves (2011), Hart (1997), Hart and Milstein (2004), Kleindorfer et al. (2005), Moody & Nogrady, 2010, Nidumolu et al. (2009), Porter and Linde (1995), and Seebode et al. (2012). Thus, this theoretical essay aims to discuss Sustainability as a sixth wave of innovation and how it may affect organizations. In Section “Cycles of change and waves of innovation”, we discuss the cycles of change and waves of innovation that are inherent to the development and survival of organizations; in Section “The sixth wave of innovation”, we analyze the sixth wave of innovation, focusing on signs that point to Sustainability as the next wave of innovation; in Section “Are we prepared?”, we discuss whether organizations are prepared for Sustainability as a new wave of innovation; and finally, we present our conclusions and suggestions for future research.

We hope that this article promotes reflection regarding this phenomenon and serves as a starting point for future discussions about what appears to be a disruption in the status quo and a new wave of innovation – that of sustainability.

Cycles of change and waves of innovationThe development and survival of organizations is susceptible to the emergence and recombination of technologies and processes that generate innovative actions, which are responsible for reshaping industry and for the current dynamic (Ansari & Krop, 2012; Utterback, 1996). However, while a disruption in innovation may represent breakthroughs on the technological front, culminating in major advances, these disruptions are difficult to manage and, as a consequence, have historically caused – and continue to cause – major problems for those who deal with them (Tidd et al., 2008).

An analysis of the behavior of market demand shows how, historically, it has been quite variable and how industry has been subject to discontinuities (Freeman, 1979). When a radical innovation is launched, this may drive existing businesses out of the market and allow new companies to emerge, so that market leaders are challenged and may lose their competitive positioning (Ansari & Krop, 2012; Utterback, 1996). This is due to these companies’ rigidity over time, which makes it difficult for them to adapt and respond to change (Tidd et al., 2008).

Evidence indicates that when a company uses a certain technology, or operates in a certain manner, it tends to protect its business format, innovating within the scope of its current activities (Archibugi, Filippetti, & Frenz, 2013; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Seebode et al., 2012; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996; Utterback, 1996). Companies tend, therefore, to innovate within the context of their previous innovation trajectory, and, as this trajectory is related to learning cycles, they often end up replicating only what they already know, so that it is usually market outsiders that innovate to a greater degree (Archibugi et al., 2013; Seebode et al., 2012). During these periods of discontinuity, new companies join existing companies and the cycles of technological change become challenging for the companies in that market (Ansari & Krop, 2012). This environment is fertile ground for the emergence of innovations from old capabilities, changes in the dominant project, a wave in the ecology of enterprises, new waves of technological change, changes of leadership at the points of inflection of technology and the invasion of technologies coming from outside the industry in question (Utterback, 1996).

These cycles of change can be represented by the model of the dynamics of innovation, according to which each and every industry is reshaped by waves of innovation that represent continuous cycles of technological and social change (Utterback, 1996). These changes give rise to a new dominant design, formed from the balance between what the market wants and what organizations are willing to offer (Utterback, 1996).

This whole process occurs within the context of the industry life cycle and undergoes three phases: the fluid phase, characterized by many product innovations and a low degree of process innovation, during which the dominant design is still unclear and the market is subject to constant change; the transient phase, characterized by a low degree of product innovation and a high degree of process innovation, as it is at this stage that one design becomes dominant and consumer needs become clearer; and the specific phase, during which there is a low degree of both product and process innovation, as the dominant design is already consolidated and the production process is known in the industry (Utterback, 1996). It is in this last phase that companies tend to face structural rigidity (Archibugi et al., 2013; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Seebode et al., 2012; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996; Utterback, 1996).

Such assertions highlight the role of Schumpeter's (1982) theory of “creative destruction”, according to which old assumptions must be “destroyed” at the expense of new ones. For companies to innovate, they must challenge both market and corporate boundaries (Ansari & Krop, 2012). This can be done through ‘organizational ambidexterity’ – a company's capacity to maintain its current operations while at the same time developing new business opportunities, thus allowing it to pursue complementary strategies (Archibugi et al., 2013; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Seebode et al., 2012; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996).

This process of “creative destruction” and the need for organizations to respond to cycles of change can be observed in the existing ‘five waves of innovation’, in the sense of Moody and Nogrady's (2010) observations. The first wave of innovation is marked by the first phase of the Industrial Revolution, which was responsible for promoting a great leap in innovation by incorporating new technologies and causing a shift from artisanal to industrial production. In its final stage, it was influenced by the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The second wave of innovation is marked by the Age of Steam, which facilitated the transportation over long distances of both people and goods, and contributed to the development and market expansion of many companies. It ended with the Great Depression. The third wave is the Age of Electricity, enabling remote communications and reconfiguring the productive potential of companies. It also ended as a result of the Great Depression. The fourth wave is that of Mass Production, which enabled companies to meet new demands, scale up their productive potential and seek new business opportunities. It ended with the Oil Crisis. Finally, the fifth wave of innovation is based on Information and Communication Technology and Networks, and is characterized by the widespread use of computers and the reconfiguration of businesses with the development of the Internet.

All these waves were accompanied by technological and social change, which was responsible for “sweeping” leading companies out of the market and giving rise to new businesses and new competitive potential (Moody & Nogrady, 2010). Each wave lasted around 50–60 years (Moody & Nogrady, 2010), which highlights the trend for new configurations even in markets that are believed to be ‘safe’ and stable (Utterback, 1996). Although the waves are responsible for forcing various companies out of the market, one observes a development trend that only seems possible when a new wave arises (Utterback, 1996).

Although it is well-established that our society is undergoing its fifth wave of innovation, this wave also shows signs of decelerating, which calls into question its continuity (Moody & Nogrady, 2010). All previous waves emerged and stagnated because of new social and technological needs, which determined other paths, which would only be achieved by a new reconfiguration (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Seebode et al., 2012.). History shows that these changes are necessary and that several market signs portend the arrival of a new wave (Utterback, 1996). This allows us to understand the conflict between the new and the old, the process of continuity and that of discontinuity, demonstrating how a new wave can change the patterns that until then had been fixed (Utterback, 1996).

The sixth wave of innovationMovements in the market indicate that a new wave of innovation is coming, driven by the depletion of the current model of capitalism and the need for reconfiguration around present environmental and social needs, thereby forming what would be the sixth wave of innovation (Fig. 1) (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Nair & Paulose, 2014; Seebode et al., 2012). Such needs revolve around the inequalities formed between countries and societies as previous waves ran their course, leading society to question not only its current needs but also what it expects for the future (Moody & Nogrady, 2010). It is within this context that the discussion of sustainability is gaining strength around the World (Barbieri et al., 2010; Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Hart, 1997; Hart & Milstein, 2004; Kleindorfer et al., 2005; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Nidumolu et al., 2009; Porter & Linde, 1995; Seebode et al., 2012), leading companies and the market to what appears to be a new dominant design, founded on sustainability as a pre-requisite for products, services and processes.

The sixth wave of innovation.

The current debate revolves around the need for companies to incorporate sustainability as a competitive factor, linking it to organizational objectives and going beyond “mere” sustainable discourse (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Hall & Vredenburg, 2012; Han et al., 2012; Markard et al., 2012; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Seebode et al., 2012). Thus, a sustainable company must simultaneously generate economic, social and environmental benefits that lead to the creation of competitive advantage and potential innovation (Barbieri et al., 2010; Kleindorfer et al., 2005; Nidumolu et al., 2009). The challenge is to create an economy that the planet is able to support indefinitely – in other words, to create an environment where businesses, humankind, and nature can coexist and develop (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Hart, 1997; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Seebode et al., 2012).

Faced with this scenario, we see a progressive expansion of the model of innovative sustainable organizations which seek both symbolic efficiency, represented by the legitimacy of society, as well as technical efficiency, thus seeking to maximize the three pillars of sustainability and transform this vision, which was previously seen as irreconcilable with economic growth, into a form of competitive advantage (Nidumolu et al., 2009). Given the convergence of social needs and competitive advantage, government, society and businesses should coordinate and combine their efforts (Hart & Dowell, 2010; Kleindorfer et al., 2005; Seebode et al., 2012.). In organizations, it is observed that sustainability has the potential to drive various types of innovation, some arising from regulation and others that are inherent in the company's own vision, which sees ways to develop competitive advantages through technologies that are linked to sustainability (Kleindorfer et al., 2005).

Sustainability may allow companies to reduce costs through the inclusion of more efficient processes, while maintaining the ability to stand out in the market, thus providing a payback on their initial investment (Gavronski, Klassen, Vachon, & do Nascimento, 2012; Porter & Linde, 1995). Using resources productively is critical to competitiveness today: nowadays it is not the firm with the most resources that achieves competitive advantage, but rather that with the most advanced technology and which makes best use of the mechanisms it has at its disposal (Hall & Vredenburg, 2012; Porter & Linde, 1995). Sustainable innovations create better products, more efficient practices and allow firms to explore new markets, many of which were previously seen as insignificant for businesses, allowing innovative firms to stay ahead of companies that seek to maintain their status quo (Nidumolu et al., 2009).

Strategies for a sustainable World must encompass population, consumption and technology, and may even improve the quality of life of the poor (Han et al., 2012; Hart, 1997; Markard et al., 2012; Nair & Paulose, 2014). To address the importance of embedding sustainability into organizational practice, Hart and Dowell (2010) revisit the natural-resource-based view of the firm, according to which companies should determine the capabilities that are necessary for a sustainable vision. This is a vision that goes beyond the ‘triple bottom line’, to discuss what would really be the beginning of a post-industrial era, if everything were to be set up on the same basis as before, but that at the same time returns to the same discussion: how will society support current “development”? (Hart & Dowell, 2010).

What we see is a dichotomy between globalization and natural resources, which puts people and the environment on one side, and market leaders responsible for deciding the future of society, but with a low degree of commitment, on the other (Senge & Carstedt, 2001). Such situation has caused not only environmental impacts, but mainly social effects, driving people away from their “human” status (Han et al., 2012; Markard et al., 2012; Nair & Paulose, 2014). This situation gives rise to the discussion of whether society is undergoing what seems to be another wave of the industrial age, rather than a wave of a new kind of economy (Senge & Carstedt, 2001) and highlights the emergence of a new wave that could present solutions to these problems (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Seebode et al., 2012).

This new wave of innovation would be ‘sustainability’ (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Nair & Paulose, 2014; Seebode et al., 2012; Senge & Carstedt, 2001), since environmentalism is emerging as a result of innovation rather than regulation. This is positive, because it means it emerges from people's greater awareness, thereby putting pressure on companies to change their behaviors (Senge & Carstedt, 2001).

Are we prepared?Whenever a new wave appears, the rules of the game change and highly competitive companies find themselves crushed in their own inflexible structures, while companies that were hitherto unknown quickly establish themselves in market (Seebode et al., 2012; Utterback, 1996). One example was Kodak, which, having been a benchmark in terms of photographic products and technology for over a century, saw its products become obsolete and its structures crushed by change. Another was Mesbla, which, despite being the market leader in non-food retail in Brazil in the 80's, disappeared in the next decade, thanks to the expansion of retail chains. While this may seem simple, many companies ignore changes and only belatedly respond to market signs, as incorporating a new attribute to the business typically requires the reconfiguration of the entire business model, rather than simply adding or altering certain ‘non-integrated components’ (Archibugi et al., 2013; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Seebode et al., 2012), especially when a new wave of innovation is imminent.

The depletion of natural resources will allow many countries to achieve superior competitive performance vs. their peers, as they seek innovative solutions to the problems at hand, and those that do not do so will lose their competitiveness (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Nair & Paulose, 2014; Seebode et al., 2012). In previous waves, those that had a clear understanding of the context of the wave developed quickly. So developing countries, for example, can achieve high growth potential based on sustainability (Nair & Paulose, 2014).

Examples of sustainable innovation in developing nations can be seen in Africa. For example: the Mobile Platform Kiosk (Rwanda), which offers solar charging for mobile devices; the Saphonians blade-less Wind Converter (Tunisia), which generates wind-power without blades that harm birds; Twende Twende (Kenya), an app to counter congestion; and Faso Soap (Burkina Faso), which repels mosquitoes that carry malaria. These innovations reflect local needs that are increasingly global, such as the need for solutions to congestion, and meet the guidelines of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), which establish sustainable development as “the direct result of science and technology”.

The way in which organizations see sustainable technologies will also change. Gavronski et al. (2012) show that companies that invest in pollution prevention technologies do not require such strict control of their waste, since prevention avoids future problems, while companies that invest little in prevention end up spending more on control, not to mention possible environmental accidents, which do incalculable damage to the organization's market value. Although some companies are not convinced of the return on sustainable practices, losses from environmental and social problems caused by their absence are evident (Gavronski et al., 2012; Hart & Dowell, 2010), as in the case of the accidents that occurred in Bhopal (India, 1984); Chernobyl (Ukraine, 1986) and Three Mile Island (Pennsylvania, United States, 1979).

Another line of research studies the stages of sustainability that a company goes through in order to become a sustainable innovative organization, and the benefits of each stage (Nidumolu et al., 2009). Nidumolu et al. (2009) assert that companies at first can see the obligation to be sustainable as an opportunity. At this stage the company is obliged to adopt certain practices due to regulation, but the sooner it does adopt them, the greater the chances that it will reap economic benefits before its competitors. At the second stage, the company can make its entire supply-chain sustainable, and starts working with suppliers and retailers to develop eco-friendly materials and reduce waste. At the third stage, the company can design products and services sustainably, as they realize that consumers prefer sustainable products and services. At the fourth stage, companies can develop sustainable business models. And finally, in the last stage, they can create platforms that support systematic sustainable innovations.

Each stage of this model requires specific actions that allow companies to develop competencies that lead to the final phase of the model. In the first stage, organizations must perceive regulations as an opportunity and adjust to them as soon as possible. For this, they must develop the ability to work with other companies, including competitors, to develop creative innovations. In the second stage, organizations must invest in techniques that reduce product life-cycles, restructure operations in order to use less energy and water, reduce emissions and waste, and audit the eco-friendliness of the supply chain. In the third stage, companies can identify which products are less harmful to the environment, encourage consumers to opt for sustainable products and develop suppliers of sustainable materials and products. In the fourth phase, companies must identify what sustainability-oriented consumers want, develop new ways to meet this demand and bring business partners into this process. In the fifth stage, organizations should map out how renewable and non-renewable resources affect business ecosystems and industries and develop business models, technologies and guidelines for different industries (Nidumolu et al., 2009). These actions may prepare organizations to face what might be the sixth wave of innovation.

In Brazil, most companies are still in the first stage of the model. However, as supply-chain management matures, and also thanks to the pressure of groups such as Greenpeace, some large organizations are moving to the second stage – they are beginning to consider the entire supply-chain in their policies. Natura and Braskem, on the other hand, are outliers and are somewhere between the fourth and fifth stages, with actions aimed at establishing a sustainable business model and building platforms that drive continuous sustainable innovation.

Technology appears, therefore, to be the most effective way to drive these innovations – enabling the development of new solutions that are less damaging to the environment and the search for alternative development strategies that are sustainable in the long term and for future generations (Bengtsson & Ågerfalk, 2011). For organizations to face the sixth wave of innovation, it is important to develop a sustainable business model that balances economic, environmental and social factors (Edgeman & Eskildsen, 2012; Gavronski et al., 2012). One of the difficulties behind the creation of such a business model is that there is little emphasis on social factors, and many companies do not know how to generate value through sustainability (Bengtsson & Ågerfalk, 2011; Boons, Montalvo, Quist, & Wagner, 2013; Edgeman & Eskildsen, 2012; Markard et al., 2012; Moody & Nogrady, 2010).

This often occurs because companies address sustainability using a technical and operational logic, meaning that it is rarely considered from a strategic or technology-development standpoint, resulting in missed opportunities (Bengtsson & Ågerfalk, 2011; Edgeman & Eskildsen, 2012; Hart, 1997). Sustainability requires a social, cultural, organizational and technological change (Gaziulusoy, Boyle, & McDowall, 2013). For a company to achieve a sustainable business model, it should seek to improve its footprint and promote “natural capitalism”, based on reducing environmental and social damage and better employing resources (Boons & Lüdeke-Freund, 2013).

Sustainable innovations must therefore meet the following criteria: have an environmental, social and economic objective; involve the supply chain; interface with customers; and adequately balance economic, social and environmental factors (Boons & Lüdeke-Freund, 2013). Companies that venture to adopt new technologies and sustainable business models must take on initial risk, but this risk may result in entry barriers for other companies (Bengtsson & Ågerfalk, 2011; Boons et al., 2013; Edgeman & Eskildsen, 2012; Markard et al., 2012; Moody & Nogrady, 2010). The challenge that the sixth wave of innovation brings lies in how to manage processes adequately (Seebode et al., 2012). In order to achieve this, companies should be ‘ambidextrous’, create architectural innovation, adequately manage their innovation trajectory and choices and seek dynamic capabilities (Seebode et al., 2012). Ultimately, the answer lies in how open the company is to understand and absorb this new situation.

To be able to create a suitable business model, the organization should align strategy, culture and structure, and managers must communicate among themselves and look both to the past and toward the future when crafting their strategies, because the challenge is to achieve innovation while at the same time making continuous improvements (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Seebode et al., 2012.). There are innovations that destroy competencies, while others create competencies, so companies must know how to deal with innovations that strengthen their existing business, while also seeking new market opportunities (Ansari & Krop, 2012; Seebode et al., 2012.). The ability to handle both is what determines the capacity of a company to adapt to change (Ansari & Krop, 2012). Furthermore, development that does not ultimately benefit society is not sustainable in the long term (Porter & Rivkin, 2012) and although innovation allows many new companies to enter the market, only those that are competitive will be able to survive the subsequent wave of innovation (Desha & Hargroves, 2011; Moody & Nogrady, 2010; Nair & Paulose, 2014; Seebode et al., 2012; Utterback, 1996).

ConclusionThis theoretical essay aimed to discuss sustainability as the sixth wave of innovation and how it may affect organizations. The impact of adopting sustainability as a path for innovation and creating competitive advantage is broad. Sustainability not only allows companies to establish an open channel to society, but changes the way the company is seen by society, its customers and employees. Innovations generated in a sustainable context are not only related to product management and the development of clean technologies, but also address relationships with suppliers and the environmental, social and economic impacts of their activities.

Political, social and environmental problems are causing companies to turn to sustainability. It is no longer a matter of philanthropy or strengthening brands through socially and environmentally-friendly discourse, but of truly understanding and addressing all these problems by incorporating solutions that meet the needs of consumers that are increasingly aware of the role companies should play. Although there is still a long path ahead, it is positive that companies are learning about the challenges of sustainability, analyzing history and seeing how many industries can be transformed.

These pressures have caused companies to rethink their practices in all dimensions. For a company to be sustainable, it must first adopt a truly sustainable business model that not only focuses on processes, services and products, but, above all, on the humanization of its workforce and social and environmental practices that form the base of the sustainability tripod. Such actions could, for instance, involve a new way to manage the organization's internal issues, which would in turn motivate other companies to adopt that model. The sooner companies respond to changes in their environments, the more time they will have to adapt and develop strategies that are economically, socially and environmentally coherent.

Each social problem is also an opportunity for a creative mind to come up with a solution. Given the multitude of problems we face, there are also many opportunities for addressing them. A society that has high levels of social inequality; transportation difficulties; pollution; poverty; water, power and food shortages; and violence, among others, certainly needs innovation. This discussion sets the stage for sustainability as the true “new post-industrial era”, since high environmental and social demands create multiple business opportunities for companies.

Innovation waves are characterized by significant economic growth and social restructuring. This is reinforced by social and governmental pressure, creating the opportunity for the development of both incremental and radical innovations that are aimed at addressing the undesirable side-effects of economic growth. This is not a matter of speculation, but of carefully analyzing the market and understanding that new demands are accompanied by changes and that these changes are converging to a World based on sustainable practices.

Based on the insights of this essay, we make the following suggestions of subjects for future research: how social issues are addressed in organizations; if there is convergence between the sustainable discourse and actual practice in companies; at what stage of Nidumolu et al.’s (2009) model organizations from different sectors are situated; what innovations sustainable practices can generate in organizations; how organizations perceive sustainability and its potential as a sixth wave of innovation; and whether organizations are prepared or not for a sixth wave of innovation based on sustainability.

The academic contribution of this article is to establish sustainability as the sixth wave of innovation. The practical contribution is to discuss the ways in which companies can prepare for what is expected to be a new wave of innovation. The ultimate goal is not to present a deterministic logic, but rather to invite reflection on the phenomenon presented here, and to serve as a starting point for deeper analysis. We therefore expect further studies on this new wave of innovation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.