The international literature on university teaching, has insisted on the need to combine a double component in the professional profile of teachers: content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge.

Regarding the content, the area of knowledge of radiology and physical medicine is made up of different medical specialties, among which are radiodiagnosis, nuclear medicine, radiation oncology, physical medicine and rehabilitation. On the other hand, the pedagogical content knowledge is framed by framework that the Bologna Declaration (1999).

Focusing on radiodiagnosis, the ideal candidates must be professionals in this medical specialty, vocational teachers and people who find in the undergraduate teaching process an opportunity to transmit their knowledge, experiences and values in an entertaining and understandable way for students who are incorporated into medical knowledge.

La literatura internacional plantea un doble componente en el perfil profesional del profesor universitario: el conocimiento del contenido (content knowledge) y el conocimiento didáctico del contenido (pedagogical content knowledge).

En cuanto al contenido, el área de conocimiento de radiología y medicina física está compuesta por diferentes especialidades médicas entre las que se encuentran radiodiagnóstico, medicina nuclear, oncología radioterápica, medicina física y rehabilitación. Por su parte, el conocimiento didáctico del contenido está enmarcado por todo lo que ha significado la Declaración de Bolonia (1999).

Centrándonos en el radiodiagnóstico, los candidatos idóneos deben ser profesionales de esta especialidad médica, vocacionales y que hallen en el proceso docente de pregrado una oportunidad de transmitir sus conocimientos, experiencias y valores de una forma amena y comprensible para alumnos que se incorporan al conocimiento médico.

This paper on diagnostic radiology teaching will focus on two fundamental aspects: a) the disciplinary content addressed in the undergraduate phase; and b) the professional profile of the diagnostic radiology lecturer. Both aspects are framed in the academic structure of the Spanish University in the context of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) and in the configuration of the knowledge area of radiology and physical medicine. With regard to the professional profile of the diagnostic radiology lecturer, Shulman1 has raised the need for the double component of content knowledge and didactic knowledge.

The knowledge area of radiology and physical medicine is composed of different medical specialties, including diagnostic radiology, nuclear medicine, radiation oncology and physical medicine and rehabilitation, as well as disciplines that are not medical specialties such as radiobiology and medical physics. It is undoubtedly a large and heterogeneous area that has to share common teaching spaces. These aspects are relevant when it comes to planning how the area is to be taught: the number of hours dedicated to each aspect; their position in the syllabus; the adaptation of the teaching staff to the time and space framework in which they must deliver their teaching, etc. All this shapes the teaching and learning process, all the more so as some of this content could clearly be considered in the clinical setting and some in the pre-clinical setting.2–6

At present, the framework within which teaching is provided in Spain conditions the attitude of those professionals who wish to enter the teaching profession. Focusing on diagnostic radiology, suitable candidates should be specialists in this area, vocational and who find in the undergraduate teaching process an opportunity to share their knowledge, experience and values in an enjoyable and understandable way to students who are looking to gain medical knowledge. This transmission of knowledge could be carried out in various formats and from many perspectives2,3: clinical placements, lectures, interactive sessions, problem-based learning (PBL), laboratory practices, seminars, simulation techniques and new techniques in a virtual setting.2–12 Knowledge of all these possibilities and the objectives pursued in each of them is very important in order to organise teaching that covers all the skills that a diagnostic radiology trainee should attain in a limited time. The overall teaching objective is to enable each student to become familiar with the fundamental aspects of the subject, essentially, to learn the profession and be able to understand and analyse medical imaging, interventional techniques and their indications as a “friendly and accessible” discipline in which he or she can move with ease.

The main objective of this paper is to provide those professionals attracted to undergraduate teaching with an overview of the situation and help them establish a path for career progression. To this end, it is important to provide an understanding of the basics of undergraduate teaching in the current academic context, highlighting the framework and strategies within which a lecturer should develop his/her role. As such, the following aspects will be addressed: firstly, the EHEA as the academic context defined by academic institutions since the Bologna Declaration, including the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) (Table 1) and the teaching strategies currently available. The second part will cover the profile of the diagnostic radiology lecturer and the skills that define his/her teaching identity.

Face-to-face and non-face-to-face teaching aspects including an ECTS credit.

| 1. Hours of theoretical and practical class attendance |

| 2. Hours devoted to targeted academic activities (seminars, research, field work, problem solving, etc.) |

| 3. Hours spent collecting information (library, databases, Internet searches, etc.) |

| 4. Hours of study for each topic and hours devoted to assessment preparation and completion |

ECTS: European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System.

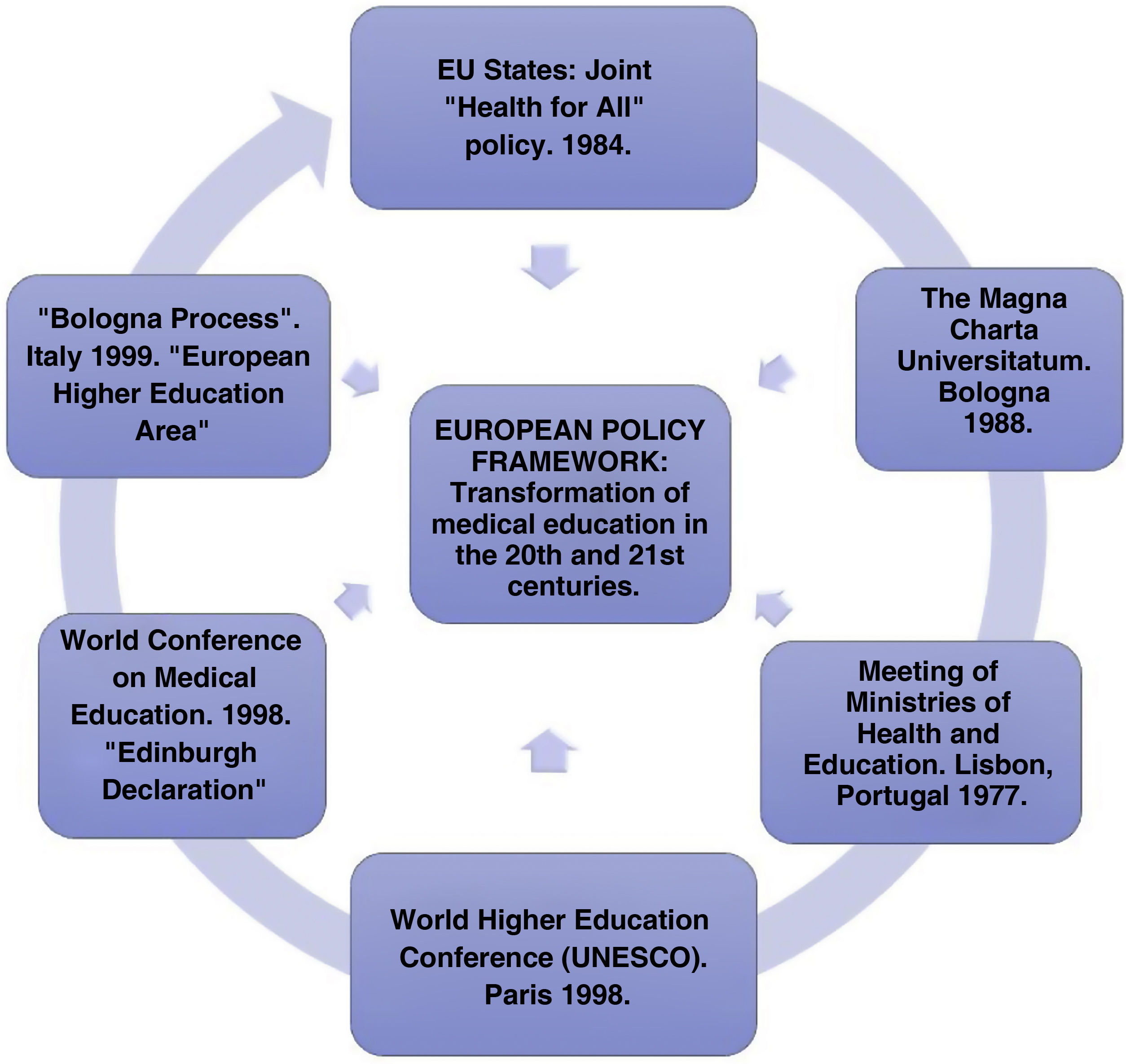

The EHEA emerged as a European education policy proposal aimed at fostering the convergence of the different higher education systems in the European Union (EU). Given that the aim was to make progress in the mutual recognition of studies carried out in any European university, a common framework was required for the organisation of these studies and professional profiles. It began with the Erasmus Programme (EEC, 1986) and has been further developed with the Bologna Magna Charta Universitatum (1988), the Lisbon Convention (1997) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Conference on Higher Education (Paris, 1998). The Edinburgh Declaration (1998) addressed the changing professional profile of teachers and lecturers, based on “training teachers as educators, not content experts alone, and reward excellence in this field as fully as excellence in biomedical research or clinical practice”. The Sorbonne Declaration (1998) marked the beginning of the process of establishing the EHEA. This was followed up by the Bologna Declaration in 1999, which called on EU member states to harmonise the various systems for regulating university education in order to increase employment in the EU and to attract the interest of students and teachers worldwide (Figs. 1 and 2).1,2

The Bologna Declaration resulted in the adoption of a series of measures aimed at achieving the previously stated objectives, including the implementation of a homogeneous degree system, the organisation of degrees into undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, which in turn include three cycles: first cycle (bachelor’s), second cycle (master’s) and third cycle (doctorate), and the implementation of a credit system to define the workload of academic units. This system measures the total work of the student to achieve the subject’s objectives (theoretical, practical and autonomous work).2

The credit system (Table 1) was one of the substantive innovations of this new organisation of studies under the EHEA because it facilitates mobility and validation of studies. It puts the emphasis on the student’s work and allows the weight of the different subjects in the curriculum to be homogenised. It is designed to avoid the hypertrophy of tasks that in some cases generated unjustified bottlenecks in the promotion of students. A basic pattern of academic engagement is established: 40 h of work per week (eight hours for five days a week) for 40 weeks. If each credit is 25 h (10 classroom hours and 15 h of independent work), the different disciplines have to adjust their overall demands (classes, study, assignments, exams, tutorials) to the total time allowed by the credits of that subject.

Current teaching strategiesThe key concept underpinning the EHEA approach can be summed up by the idea of a “shift from teaching to learning”. This proposal represents a 180° turnaround from the idea of conventional teaching, which is more centred on teaching (transmission of knowledge by the teacher for the student to learn and assimilate) than on the learning process that each student must develop. In fact, learning was outside the remit of the teacher and was understood as something for which each student was responsible since it depended on his or her intelligence, motivation and effort.

The teaching strategies of the new university pedagogy must therefore respond to the general idea that the teacher’s mission is not so much to offer good explanations but to make students learn. Good teaching no longer depends only on mastering the subject and knowing how to explain it, but also on being able to put together contexts that facilitate the learning of all our students. Finkel13 dared to talk about “teaching with your mouth shut”.

There are multiple teaching strategies in the scientific field of diagnostic radiology that include all the methodological modalities and formats available in teaching practice: face-to-face, virtual or hybrid teaching; individualised or group teaching; expository or interactive teaching; theoretical or practical teaching; expository, laboratory or clinical sessions; individual or group tutorials; etc. These will not be analysed here because other authors have already done so in this series of articles.14

What we would like to stress is that, whatever the modality used, it should, as far as possible, meet the general conditions of variety and relevance. Variety avoids monotony and demotivation, while relevance helps to reinforce the value, meaning and usefulness of what is offered to students.

In meeting the Bologna principle of putting learning at the centre of teaching, another characteristic of the methodology must be to take into account two of the basic conditions of all learning: the first is that individuals learn best if they are able to relate some things to others (knowledge functions as a network structure in which its component units are as important as the relationships that exist between them); and the second is that individuals learn best if they are able to give meaning to the things they study (meaningful learning as opposed to blind, literal, rote learning).

To close this section, we would like to mention the concept of “choreography” as a different way of understanding and planning our teaching methodology. Oser and Baeriswyl15 used the metaphor drawn from the world of dance as a different way of conceiving and organising teaching. Zabalza Beraza et al.16 have applied it to university teaching. Talking about teaching choreographies leads us to a systemic consideration of what happens in universities: we teachers are simultaneously dancers in the choreography set by the institutions (we will never be able to teach effectively if the institutional choreography is not good or does not foster it).

The diagnostic radiology teacher/lecturerRole of the diagnostic radiology teacher/lecturer in the teaching processWith regard to teaching, the teacher forms the core of the teaching process, acting as a mediator between the content and the learner by using the most appropriate teaching methods. As Chevalard17 pointed out when defining teaching as a process of didactic transposition, it is a matter of translating savoir savant (the scientific knowledge of experts) into savoir enseigné (the same knowledge adapted to give students access to it). Chevalard approached it from the field of mathematics, but it can also be applied to the various fields of medicine.17 Teacher mediation is an active (never passive) process in the transmission of knowledge. The attitude adopted by the teacher towards his or her students is also important, since learning will be greatly facilitated if it is framed in a positive, dynamic and motivating way.

In order to adequately fulfil this mediating role, university lecturers need special “expertise” that goes far beyond the mere mastery of the discipline they teach.18 Shulman, a professor at the University of Michigan, has insisted on the double dimension of this “teacher training”: content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge.1 Based on this necessary combination, the diagnostic radiology teacher should possess the following qualities:

- •

A thorough knowledge of the subject to be taught. It is obvious that no lecturer can be required to be a specialist in each and every one of its parts, but he/she must have an essential knowledge of them, progressively enriched through the results obtained from his/her own research and that of other authors.

- •

Didactic ability. It is essential to know how to pass on knowledge. This skill is a function of innate ability, the development and adoption of teaching techniques, and the motivation or vocation to teach. University lecturers should not consider teaching as a nuisance that hinders their clinical and research work, as this would make it more difficult to effectively pass on their knowledge. A basic quality teacher’s must have clarity of verbal presentation, not to be confused with clinical knowledge and skills or professional brilliance.

- •

Availability. Teaching should not be limited to lectures or set tasks, but should be accessible to the learner, and such availability should be evident. “Helping” and supporting students is at the heart of the teaching profession.

- •

Enthusiasm and a vocation for research. To these characteristics I would add excitement, undoubtedly an enormous driving force, which gives freshness and dynamism to teaching. Perhaps the most important of all those described and which can replace any of the above.

With regards to research, university lecturers must view it as one of the means at their disposal for their continuing medical education, which will be constantly reflected in the quality of teaching given. Lecturers must also be able to encourage criticism, define learning objectives and promote the acquisition of intellectual discipline. The diagnostic radiology teacher, like any other, must be vocational, dedicated from a teaching perspective, with robust academic and methodological preparation, keeping up to date with the latest developments in his or her knowledge area. Unquestionably an arduous task that in the times we live in does not leave much opportunity for relaxation from these daily chores. These qualities are mostly not innate and must be learned.

Skills of the diagnostic radiology teacher/lecturerOne of the key concepts incorporated in the Bologna philosophy is skills and abilities. These could be defined as the set of knowledge, skills and attitudes/values needed to carry out some kind of professional activity. What differentiates skills and abilities from learning is that, in this case, we are not talking about knowledge for knowledge’s sake (rote knowledge) but rather knowledge that is transferable to professional practice. Given that the role of diagnostic radiology teacher encompasses elements from two professions (medical and teaching), both are constructed on the basis of the repertoire of skills and abilities that each of them demands. Medical skills are usually clear, whereas teaching skills are less so. This paper refers exclusively to the latter. In this sense, the diagnostic radiology teacher should possess (first at a basic level and then at progressively higher levels) the following teaching skills:19

- -

Basic and operational knowledge of university education. This is a precondition for integration into the teaching profession. Lecturers are familiar with university life from their experience as students, but they need better and more relevant “inputs” about this institution (its rules, its demands, its culture), about university teaching (what the profession entails, what commitments are made, under what conditions it must operate, etc.) and about students (what they are looking for, what motivates them, how they learn). Without being sufficiently skilled in this area (which requires role-specific knowledge, skills and attitudes), all other skills are likely to be misunderstood.

- -

Planning the teaching–learning process. An ability to plan is essential. It is not always the case that new teachers will need to do this work. In many cases it will already be done by areas and departments, which teachers will be able to modify to make improvements.

- -

Selecting and preparing relevant, up-to-date and useful subject-based content. An important aspect of teaching is being able to choose the best content, the most suitable for the level of the learner for whom it is intended, and at the same time to reconcile it with the didactic ability of the teacher.

- -

Communicating this content clearly and meaningfully to their students. Traditionally, the most important characteristics of a teacher used to be that he/she should explain the subject well, be a good communicator (speak well and clearly) and be able to capture the student’s attention. This verbal competence is nowadays in conflict with the use of telematic media. It is no longer as important to talk as it is to communicate well, whether verbally or telematically, so that your students can access good information quickly and securely. An important component of all communication is the affective connotation of the messages and of the communication process itself: personalising messages, giving them affective content, “conveying passion” and awakening the learner’s interest in the message he/she receives.

- -

Designing the working methodology and organising the learning activities and tasks. This requires a familiarity with the most up-to-date and effective methodologies and being able to use them. It is important to note that any methodology includes four basic components with which teachers must know how to work: a) the organisation of space and time, routines; b) the way information is provided; c) the development of the tasks and practices of each subject; and d) interpersonal relations.16

- -

Relating to pupils. This is a core skill in education: research has shown that the dynamics of relationships with individual teachers have a greater formative impact (and will be more remembered by students) than the teacher’s mastery of the subject matter. It is, moreover, a cross-cutting skill since interpersonal relationships constitute a basic component of the different skills. This is particularly relevant in very large groups, where individual contact with the learner is more difficult. This gives more significance to the clinical placements where associate professors of health sciences (PACS) and teaching assistants have the opportunity to develop a close relationship with the student, ideally one per tutor.

- -

Tutoring and providing feedback to students. This is a substantial aspect of the teacher’s professional profile that is being hampered by the massification of higher education. In the case of diagnostic radiology, as mentioned above, clinical placements are an opportunity to mitigate these deficiencies by extending this skill to all teachers and tutors involved in teaching.

- -

Assessing. The importance of assessing in university education systems is obvious. The university not only trains, but also awards a professional degree and accredits the holder. In many cases, the whole curricular structure pivots on the axis of assessment. There are multiple ways to qualify. Continuous assessment should occupy a preferential position in these processes, complemented by examination in its many forms.

- -

Reflecting on and researching teaching. This is an important aspect in order to consider improvement processes. Practice alone does not help to improve teaching. Professional knowledge is always built through reflection and research into practice. In medicine, this is well known: many years of professional practice may improve our basic skills, but will not increase our knowledge or professional competence. Teaching practice needs to be checked either through comparison with other colleagues, or through assessment of our practice and/or research into central aspects of what we do. This is still rare at university level, although in recent years a number of national initiatives with this profile are emerging.

- -

Identifying with the institution and working as a team. This is clearly a cross-cutting skill. All the others are affected by the way in which we teachers feel integrated into the organisation to which we belong and are willing (attitude) and able (technique) to work together with colleagues. As in the case of students and learning, just as in the case of teachers, the factor that best predicts improvement in teaching is engagement, i.e. the commitment, involvement and effort with which one carries out one’s work. This would be the content of the tenth skill: knowing how to and wanting to work together in a given institutional context; accepting that we are developing an institutional project for training future medical professionals.

If teaching is a profession as we have been referring to it, it implies not only that its practice requires possession of the skills and competences that define the professional profile in question (in our case: teaching in the area of diagnostic radiology in Health Sciences), but also that it implies placing the professional teaching career within the framework of “life-long learning”. This is a commitment that diagnostic radiology experts must embrace not only as physicians but also as teachers. All the skills described above must be learned and their mastery will be progressive as we accumulate experience and teacher training.

At present, all Spanish universities offer teacher training programmes. However, these formal proposals represent just one pathway. There are many others through which teachers can improve their skills. Two of them are particularly effective:

- -

Reviewing the role of teaching and any related incidents that may occur with colleagues. This is something that medical professionals are used to through clinical sessions. This is less often done in relation to teaching, but would be equally positive for life-long learning. A great Canadian educationalist, Hargreaves,20 rightly pointed out that all professional learning is always “choral learning”, i.e. learning with colleagues.

- -

Research into one’s own teaching: reviewing what one is doing through reflection and, even better, investigating specific aspects of one’s own work (basic concepts of the subject; aspects that present the most difficulties in learning; erroneous ways of reading images or sounds detected in tests, etc.).

The trajectory of the diagnostic radiology teacher is conditioned by the current teaching figures, which vary from one Spanish Autonomous Community to the next, and the need to attain the corresponding accreditation for each of them, with their varying degrees of difficulty. The initial form of joining the teaching process could arguably be the position of clinical tutor, teaching assistant or others, whose name changes depending on the Autonomous Community. This position is recognised by the corresponding departments and areas and by the regional health system, and is valued in the employment agency, professional career and others, which is an incentive to participate in practical teaching. Recently, the Spanish National Agency for Evaluation and Accreditation (ANECA) has also begun to recognise this position. The next step could be the position of associate professor of health sciences or associate professor, both with unique characteristics that differentiate them. In both cases, accreditation is not required. Appointment as an associate professor of health sciences enables the professional to take on practical teaching as part of his or her work as a healthcare professional; the person who chooses this position must therefore have a contractual relationship with the reference clinical hospital and this connection will be lost when it ceases to exist. Some universities grant associate professors of health sciences the chance to give up to 80 h of expository teaching; a great opportunity to get a glimpse of this type of work and to forge a professional future, starting this activity with a small number of hours. The associate professor’s sole purpose is interactive and expository teaching, which they cannot perform during their working hours as a healthcare professional, if applicable, although in this case it would not be necessary, as they could be a professional in private practice.

An intermediate position could be a doctoral assistant. Accreditation for this role is not required, only a doctorate. The position comes with a full-time and binding six-year contract (Article 78.d. “LOSU” [Organic Law of the University System]) that may or may not be continuous depending on the centre. The above makes this position unappealing for specialist doctors in general, and also for diagnostic radiology professionals, and this is not an isolated fact for this specialty.

The figure below could be hired as a doctor. Specific accreditation is required from a national or regional accreditation agency. It is within the scope of employment and is linked to the candidate’s healthcare post. From this point onwards, the following figures, either as public servants or, in exceptional cases, as employees, would be tenured and tenure-track professors, both of which require specific national accreditation; some autonomous regions also grant employment accreditation.

The current Organic Law of the University System (LOSU), which came into force on 12 April 2023, has changed this landscape somewhat, fundamentally by abolishing the position of contracted doctor, which is replaced by permanent lecturer. In addition, associate professors are now permanent and have a maximum commitment of 120 h, and there is now the possibility of the emergence of positions within the labour setting of tenured and tenure-track professors, roles that may be accredited by autonomous community agencies. Within the category of permanent tenure-track faculty, there is the possibility for tenured and tenure-track professorships to be developed. It will be up to the regional governments, in the corresponding legislative development and within the scope of their competences, to decide whether or not to create this position.

As defined in the law, accreditations for all types of teaching staff (public servant or employee) may be issued by both ANECA and the regional agencies. The LOSU establishes a deadline for both to define and develop homogeneous criteria. The LOSU thus outlines two scenarios, one pathway as “public servant” staff and the other as staff in employment, accredited by both regional agencies and/or ANECA, including the positions of tenured professor and tenure-track professor (Fig. 3).

ConclusionsThe diagnostic radiology lecturer must be a professional who, in addition to his or her clinical knowledge, has an understanding of the teaching situation demarcated by the EHEA, is familiar with the teaching techniques available to him or her and the current teaching philosophy, and sees in this profession the opportunity to convey and facilitate the knowledge of his or her subject, in a friendly and understandable way, to students who are looking to gain medical knowledge.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: JMCV.

- 2.

Study conception: JMCV.

- 3.

Study design: JMCV and MAZV.

- 4.

Data collection: not applicable.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: not applicable.

- 6.

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7.

Literature search: JMCV and MAZV.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: JMCV and MAZV.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: JMCV and MAZV.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: JMCV and MAZV.

The authors declare that this paper received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.