Edited by: Dr. José Luis del Cura Rodríguez - Servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, Hospital Universitario Donostia, Donostia-San Sebastián, España

Last update: August 2022

More infoAlthough ultrasound-guided interventional procedures have resulted in great advances in many fields of medicine, this approach has revolutionized endovascular procedures.

This paper aims to review the basic principles to develop a strategy to follow in ultrasound-guided treatments of varices in the lower limbs, as well as to provide a brief overview of the main endovenous techniques available nowadays.

We divide these techniques into those that use catheters to occlude straight saphenous axes (thermal / non-thermal ablation) and other options, such as foam sclerotherapy, which can be used in all types of varices, even in those originating in the pelvis.

Si en muchos campos de la medicina, el intervencionismo ecográfico ha aportado grandes avances, sin duda en lo que respecta a las terapias endovenosas ha supuesto una revolución.

El presente artículo pretende repasar los principios básicos para desarrollar una estrategia a seguir en los tratamientos ecoguiados de varices en los miembros inferiores. Así mismo, busca transmitir una breve perspectiva sobre las principales técnicas endovenosas disponibles en la actualidad.

Dichas técnicas las dividiremos principalmente en aquellas que se sirven de un catéter con el fin de ocluir los ejes safenos rectos (ablación térmica/no térmica) y aquellas otras opciones, como es la esclerosis con espuma, que permite su uso en todo tipo de varices, incluso las de origen pélvico.

Varicose veins of the legs are one of the most common signs of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). They are included in classes C2-C6 of the Clinical-Etiological-Anatomical-Pathophysiological (CEAP)1,2 classification (Fig. 1).

Varicose veins are a chronic disorder in which symptoms can vary greatly in severity and affect patients' quality of life.

Once conservative measures have been applied, the indication for invasive treatment of varicose veins of the legs generally derives from clinical symptoms (pain, heaviness, cramps, etc.), severe trophic changes in the skin or the existence of previous complications (thrombophlebitis, ulcers or vein rupture). Cosmetic reasons must also be taken into account.

The last twenty or thirty years have seen the development of ultrasound-guided endovenous techniques for the management of CVI, such as thermal ablation (endolaser, radiofrequency and steam ablation), mechanical occlusion chemically assisted ablation (MOCA) and purely chemical ablation (liquid and foam sclerotherapy), and occlusion with cyanoacrylate glue.

This revolutionised the treatment of varicose veins, as Doppler ultrasound had done for the diagnosis of CVI, to the point that in 2013 the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended that (endolaser or radiofrequency) endovenous thermal ablation and ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy should be offered as a first-line treatment option instead of conventional surgery.3

The aim of this article is to describe the basic principles that should govern the ultrasound-guided treatment strategy for varicose veins of the legs and to briefly review the main techniques currently available.

Treatment strategyBefore considering any type of intervention on varicose veins in the legs, it is essential to have a sound knowledge of the pathophysiology, anatomy and haemodynamic abnormalities underlying CVI.

Once the indication for treatment has been established and after the pertinent health and dietary measures (use of elastic stockings, frequent physical exercise, etc.) have been implemented, the first step is to perform comprehensive Doppler ultrasound mapping with the patient standing.

It is best to adhere to a specific examination method to ensure that the investigation is performed systematically.4

Diseased segments with confirmed reflux exceeding 0.5 s after manual compression must be identified, as must the origin of the different shunts.5 These usually originate from:

- •

A saphenous trunk or secondary network (great, small or accessory saphenous or Giacomini vein).

- •

Cavernomas or neovascularisation related to previous surgery, pelvic origin or incompetent perforator veins.

The aim of interventional treatment of leg varicose veins is to eliminate refluxing segments or segments with incompetent valves which are causing a haemodynamic overload on the limb. How this is done will depend on the strategy chosen.

Classically, there were various recognised approaches for stratifying the treatment of varicose veins: the Swiss technique (Sigg school), the Irish technique (Fegan school) and the French technique (Tournay school). The French school, probably the most widespread, promotes a staggered eradication of the refluxing segments, from the cranial or proximal to the caudal or distal segments.

This approach makes it possible to gradually de-pressurise the distal segments. As a result, over the treatment period, the varicose veins being treated have smaller and smaller lumina with less and less potential for complications (Fig. 2).

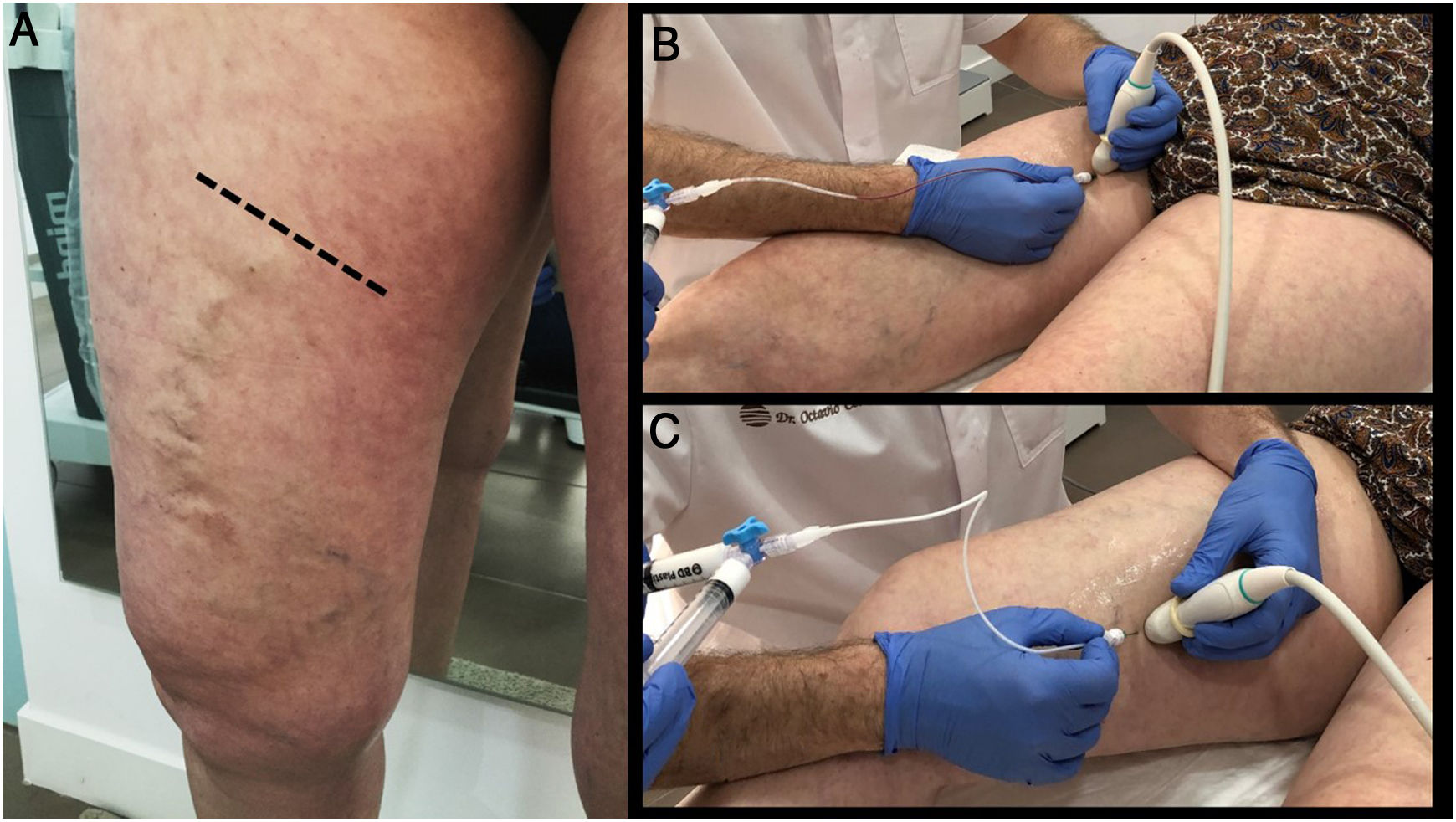

The importance of good planning. The patient in the figure only underwent treatment of the great saphenous vein (proximal or cranial segment), responsible for the tributaries that run over the knee. In subsequent follow-up, they can be seen to have virtually disappeared. Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy of these tributaries, which now have a much smaller lumen, must be done in a second procedure. The treatment was performed with MOCA ablation of the great saphenous vein using a ClariVein catheter. It achieved good occlusion, even of dilated trunk segments (18 mm).

This means that percutaneous varicose vein treatments are staggered over time, unlike conventional surgery, where the aim is to eliminate or correct the underlying problem in a single procedure.

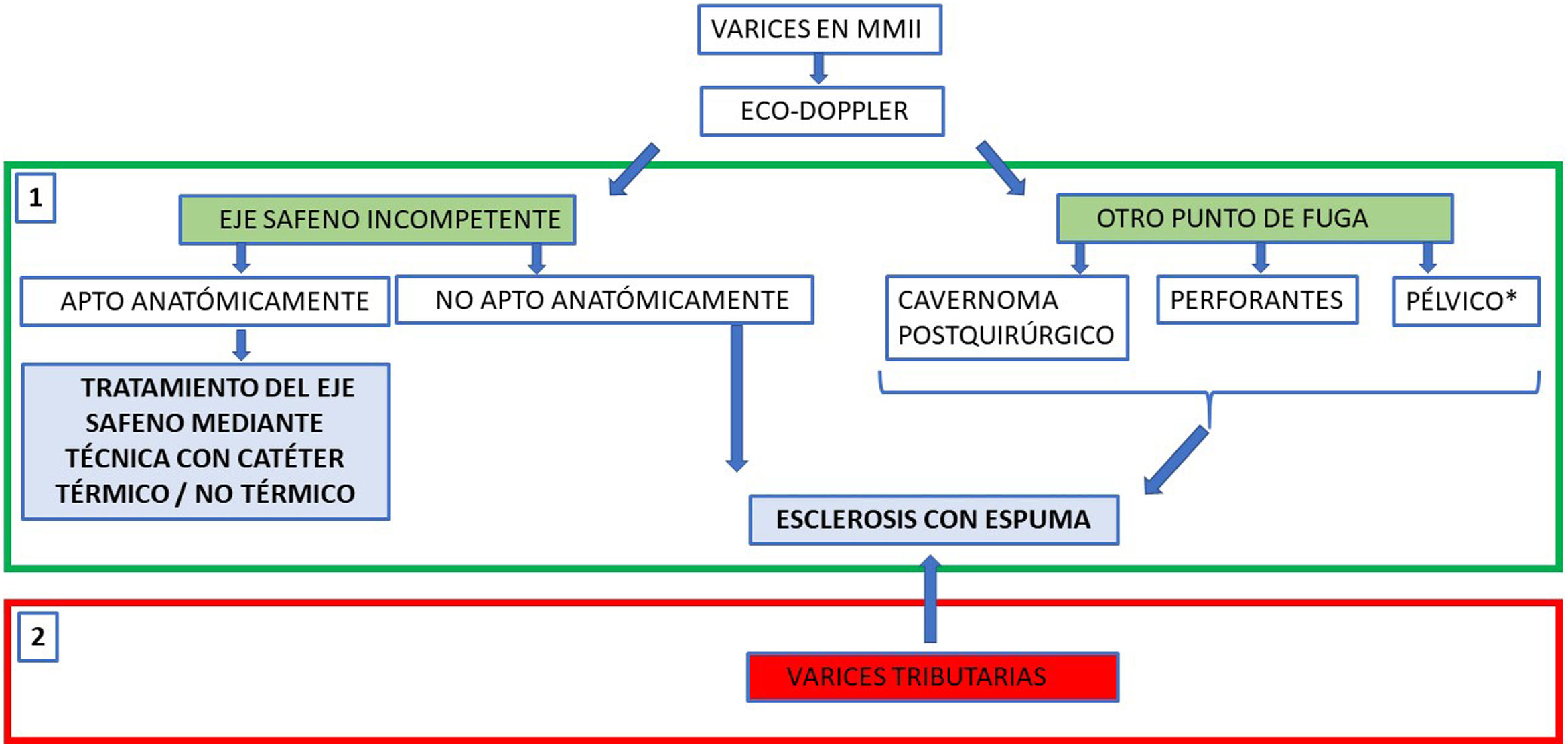

To summarise, the process can be divided into two phases (Fig. 3):

- 1

In the first phase, the priority is the occlusion of proximal segments. When the origin of the reflux is incompetent but anatomically adequate saphenous axes, catheter techniques are preferred because of their better long-term occlusion rates. In cases in which a catheter technique cannot be used to occlude the proximal segments, such as postoperative recurrence, tortuous varicose veins supplied by a pelvic leak point or incompetent perforator veins, sclerosing foam or even glue should be directly injected.

- 2

In the second phase, tributary or distal varicose veins are treated. These, which have decreased in calibre after being de-pressurised, will respond better to ultrasound-guided injection of foam sclerotherapy.

General outline of how to design a percutaneous treatment strategy for varicose veins in the legs, depending on the location of the proximal leak point or start of reflux. One variant of foam sclerotherapy, to occlude proximal leak points not suitable for a catheter, could be direct injection of an adhesive agent (cyanoacrylate), though for very marginal use. In reflux of pelvic origin, if the patient has symptoms of pelvic congestive syndrome, the treatment of choice would be embolisation of the gonadal veins. However, sclerotherapy from the perineal area may be enough to control leakage to the legs.

Regardless of treatment approach, subsequent use of (30−40 mmHg) compression stockings for about two or three weeks is recommended (unless cyanoacrylate is used).

There is no consensus with regard to prescribing prophylactic low–molecular-weight heparins, except in patients with a history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), recurrent thrombophlebitis, obesity or known thrombophilia. Patients should undergo ultrasound and clinical monitoring at least after one, three and six months.6

Saphenous trunk ablation with catheter-based techniquesAs mentioned, there has been a proliferation of different types of ultrasound-guided endovenous techniques for occlusion of diseased saphenous veins. However, one limiting factor is that these systems require suitable anatomical conditions for navigability to be effective: no tortuosity in the saphenous vein, no occluded segments, preferably subfascial trajectory, limited diameter, etc.

As yet, no single or standardised protocol which clearly prevails over the rest has been established. Thermal ablations, however, have the largest amount of long-term follow-up to draw on, and can be considered the gold standard among these procedures. Nevertheless, in the end, the balance will be tipped one way or another by the particular virtues of each modality, the preferences of the operator and the context in which they are to be carried out.

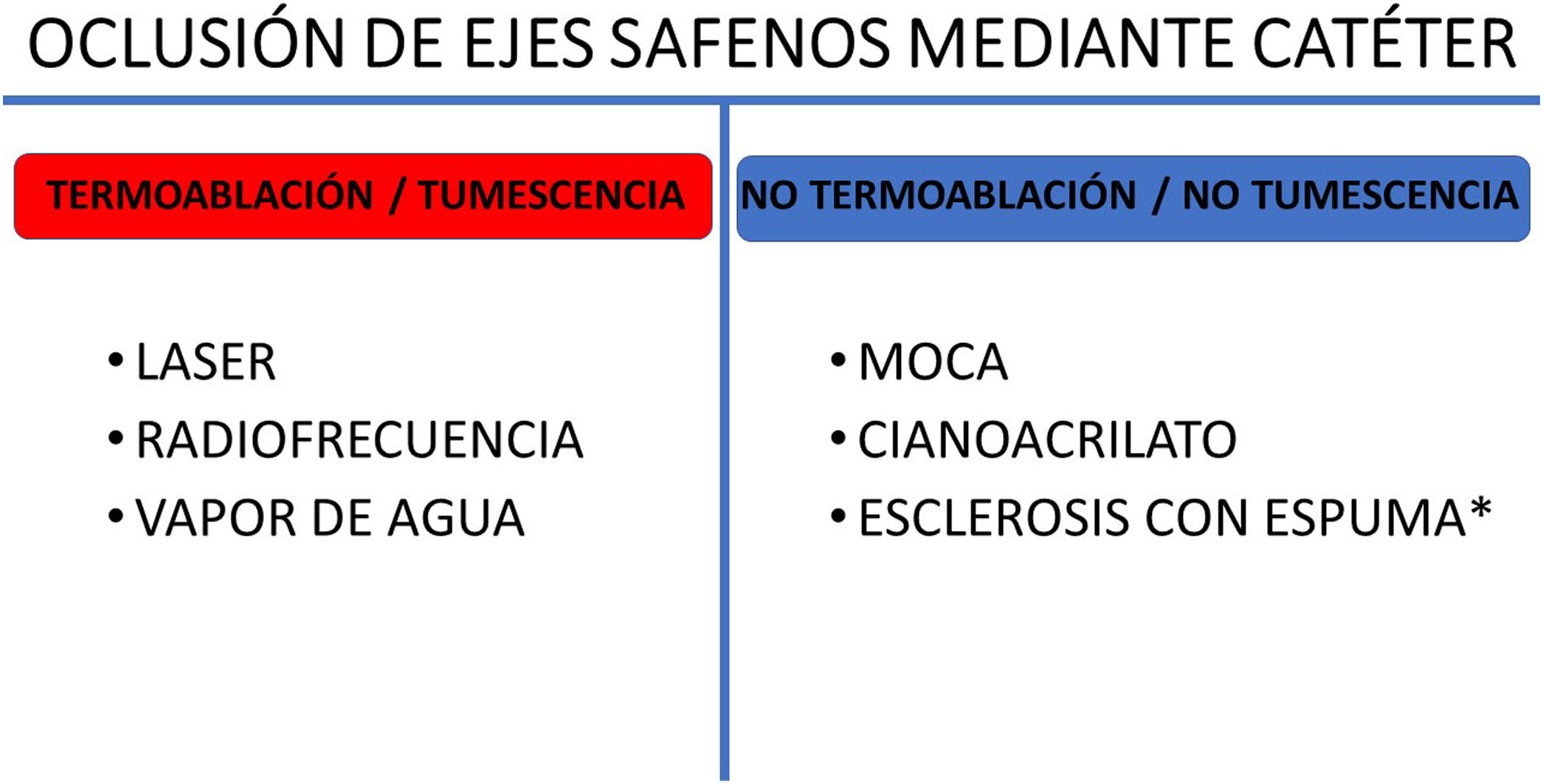

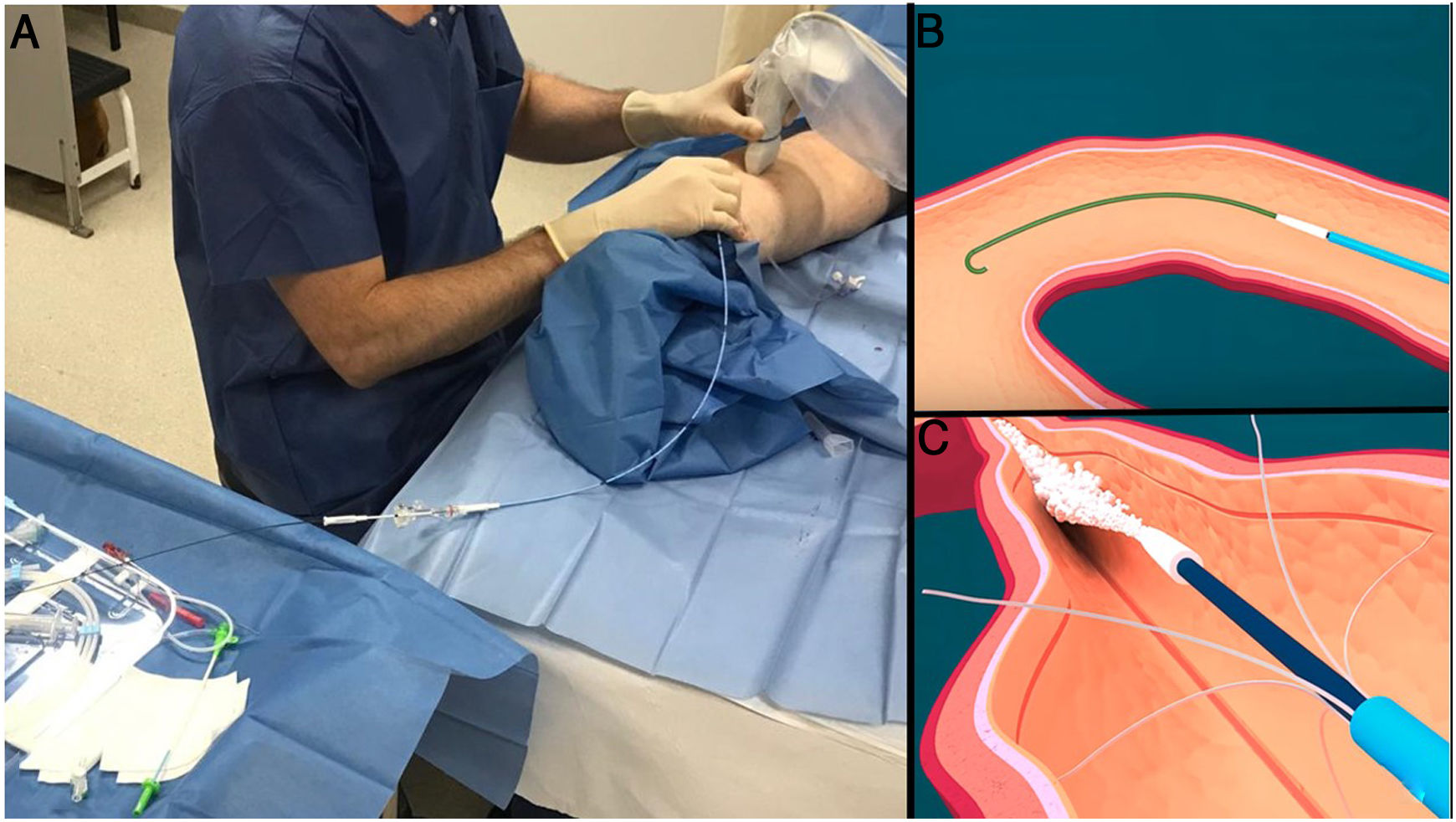

There are two main families of techniques, depending on whether a heat source is used to damage the vein (thermal ablation) or other mechanisms are used to occlude the incompetent saphenous vein (non-thermal ablations). The techniques can also be differentiated depending on whether or not they require the use of tumescent anaesthesia (Fig. 4).

Perivenous tumescent infusion involves the injection of large volumes of a saline solution containing lidocaine, and at times even bicarbonate and adrenaline. It is injected into the saphenous compartment in order to collapse the vein, separate it from structures that may be damaged by heat (skin and saphenous nerve) and anaesthetise the trajectory to be treated.

Thermal ablationThis group includes endovenous laser, radiofrequency and steam ablation (in disuse).

Due to the mechanism of action based on using a heat source to cause parietal damage in the vein, as mentioned above, an infusion of tumescent fluid into the perivenous tissues is necessary with thermal ablation techniques.

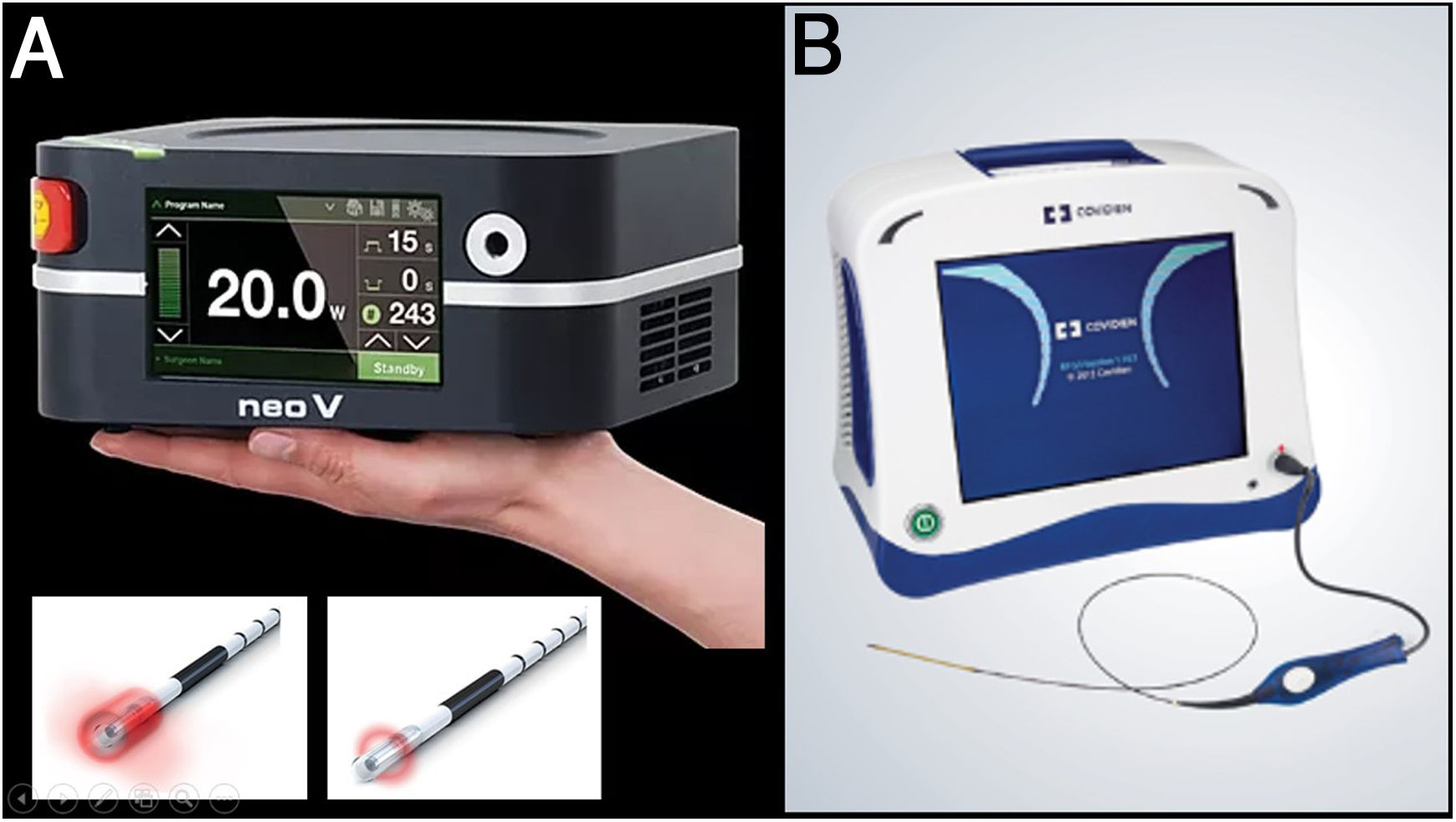

In 1999, Carlos Boné described endovenous laser use as a treatment method for saphenous trunk incompetence. Since then, heat-based ablation techniques have been the most widely used and the most corroborated techniques, such that international guidelines currently recommend thermal ablation as a first-line treatment in saphenous vein reflux3,6,7 (Fig. 5).

A) The first endolaser fibres to become available were 810 nm. Soon after the 980 nm and 1470 nm wavelengths appeared. These two fibres are the most widely used today. Recently 1980 nm devices have started to appear. The essential difference between the wavelengths is the chromophobe they are targeting (the 980 nm lasers target both water and blood, and the 1470 nm and 1980 nm lasers target only water, resulting in more parietal damage with fewer adverse effects). B) Radiofrequency acts by using non-ionising electromagnetic radiation to raise the temperature of the tissues (ideally, only the vein wall) above 120°C.

Catheter-based saphenous vein ablation methods have demonstrated similar or superior effectiveness to conventional surgery as well as higher and more consistent occlusion rates than foam sclerotherapy.8

Using ultrasound guidance, depending on the technique used, the active end of the catheter should be placed about 2−4 cm from the saphenofemoral junction.

The reasons for starting the ablation away from the saphenofemoral junction are to preserve pudendal, epigastric and circumflex venous return and to minimise the risk of DVT.

Being purely percutaneous and ultrasound-guided, these techniques were seen as revolutionary, as they offered the option of treating patients on an outpatient basis and even potentially outside the conventional operating theatre. Both radiofrequency (RF) and endovenous laser techniques have improved over time and are well standardised, especially the RF ClosureFast® system (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States), which performs segmental and overlapping ablations every 7 cm.

They have similar advantages and disadvantages. Both have occlusion rates of around 90%–95%, with long-term follow-up. However, the need for tumescence makes the procedures longer and more uncomfortable for the patient. Also, as mentioned, they share potential complications in terms of damage to neighbouring structures (skin burns, nerve injuries, etc).

Non-thermal ablationAfter thermal ablation procedures were introduced, more methods for saphenous vein occlusion began to emerge. Two methods in increasingly widespread use are MOCA and occlusion using cyanoacrylate.

These techniques have shown occlusion rates similar to laser and RF techniques, although they generally have less long-term follow-up. However, as they do not require tumescent anaesthesia, they are ideal for performing outside the operating theatre, in addition to being faster and much less painful for the patient during and after treatment.9

As an added advantage, as they do not use a heat source, there is no risk of nerve or skin damage, meaning ablation can be performed on the entire saphenous vein as far as the ankle.

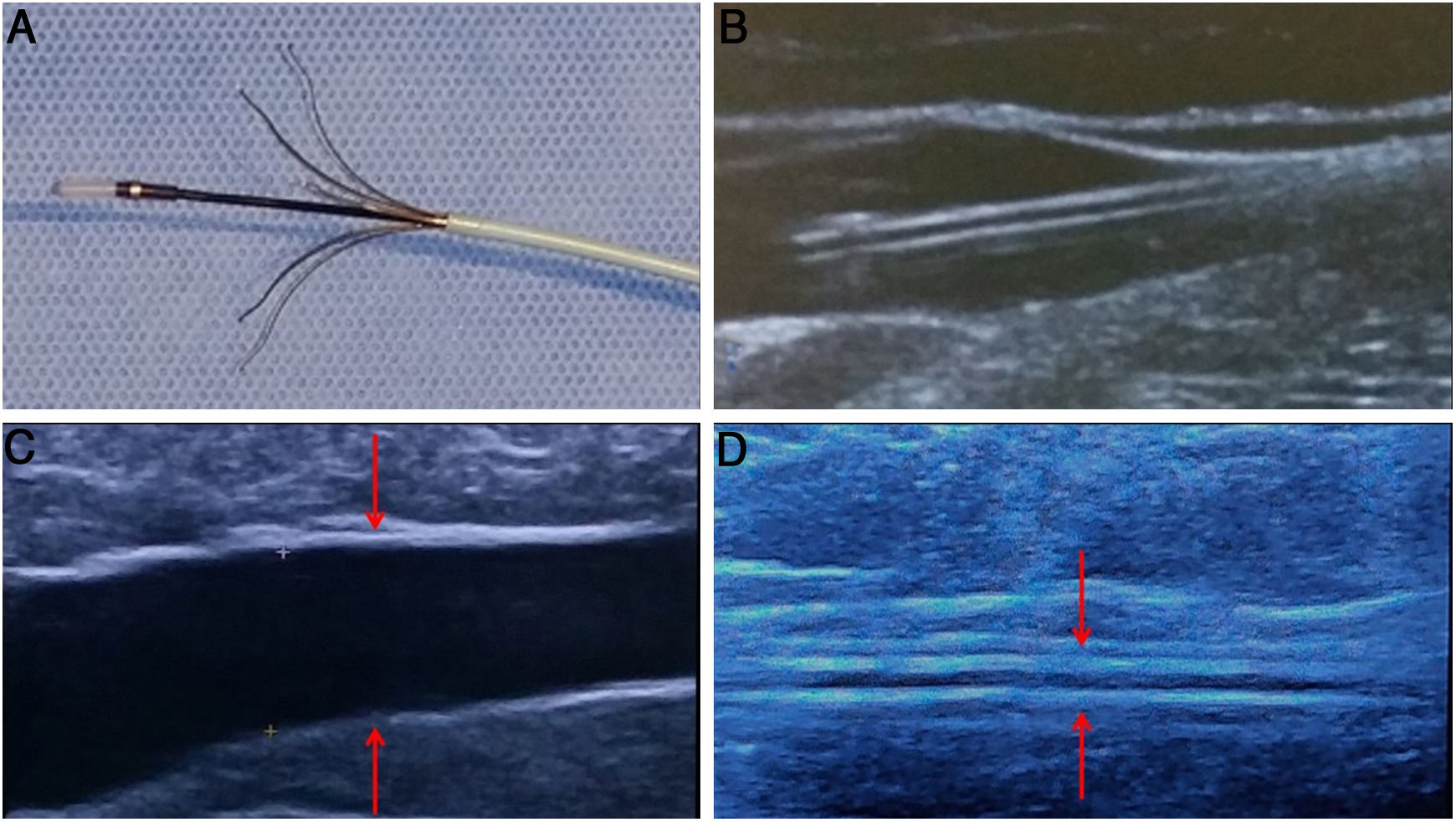

MOCAThere are currently two devices available on the market: ClariVein® (Merit Medical, South Jordan, UT, United States) and Flebogrif® (Balton® Warsaw, Poland).

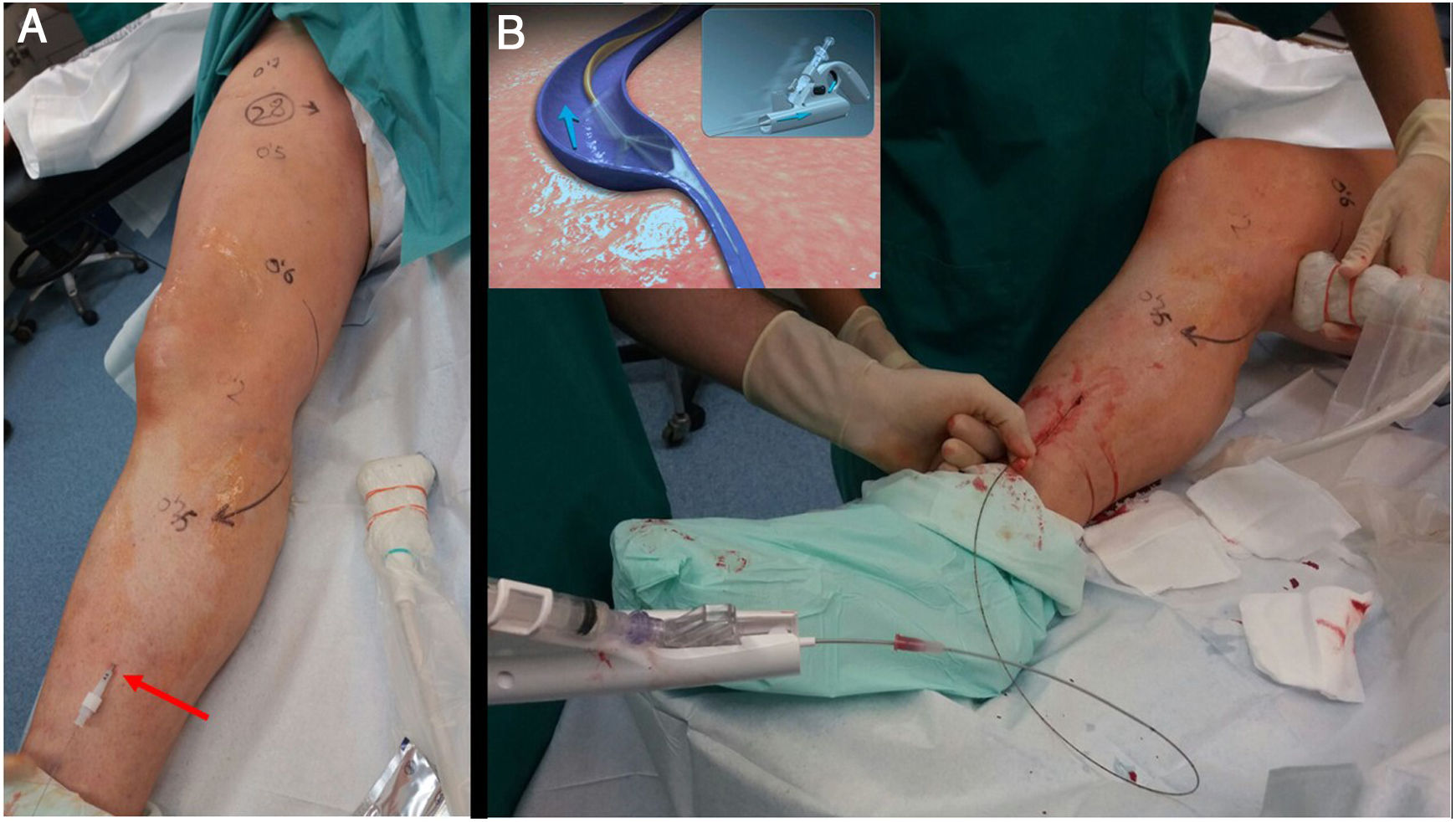

ClariVein® was invented by an American interventional radiologist (Michael Tal) who was inspired by the spin cycle of a washing machine. He needed a non-thermal method to treat a persistent sciatic vein without damaging the sciatic nerve in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. ClariVein® combines two mechanisms to damage the endothelial wall of the vein: the metal terminal generates friction by rotating at 3500 rpm and, at the same time, sprays sclerosing fluid (polidocanol or sodium tetradecyl sulfate) (Fig. 6).

A) Non-thermal ablation techniques allow long treatment routes (up to the perimalleolar area) without risk of temperature-related nerve damage. B) Treatment of the great saphenous vein along its entire length using a ClariVein 85 cm catheter. The catheter must be withdrawn very slowly with gentle injection of polidocanol or liquid STS at 2%. The rotation of the metal end of the catheter damages the venous endothelium and circumferentially distributes the sclerosant.

The vortex effect created by the rotation causes the sclerosant to cover 360° of the vein wall; this, added to the mechanical damage, achieves occlusion rates of 91%-96% at two years and 87% at three years.10,11 Drawbacks include the fact that it can be painful if the metal rod gets caught in a branch, and that it does not allow for the use of a guidewire in tortuous segments. However, its shape and low profile endow it with very good navigability.

Flebogrif® is a device that was placed on the market more recently, although it was conceived even earlier. Initially it was the fruit of a research thesis at the University of Lublin (Poland) and went unnoticed. However, it was subsequently taken up and improved by T. Zubilewich in collaboration with Balton®. It consists of a 6 F catheter with five nickel titanium terminals bearing slightly sharpened tips which are exposed by performing a pull-back manoeuvre. These terminals damage the endothelium of the vein as they are withdrawn. During withdrawal, from the junction to the entry point, 3% polidocanol or sodium tetradecyl sulphate foam is injected at a rate of 1 mL every 5 cm (Fig. 7).

As a distinguishing characteristic, an initial pass can be made with the terminals exposed, but without injecting foam, in order to induce spasm in the saphenous vein and optimise the effect of the sclerosing foam (Fig. 8).

A) Detail of the Flebogrif® catheter with the exposed "cutting" metallic elements and the corresponding ultrasound image (B). This device allows a first pass to be done with erosion of the inside of the vein alone, without foam injection. This causes a spasm in the saphenous trunk which enhances the subsequent action of the foam (C).

Notably, it is extremely simple and versatile to use (catheter over a 0.035″ guidewire), virtually painless for the patient and capable of treating larger-diameter axes (up to 20 mm). It has been ascribed an occlusion rate of 92% at 12 and 24 months.12,13

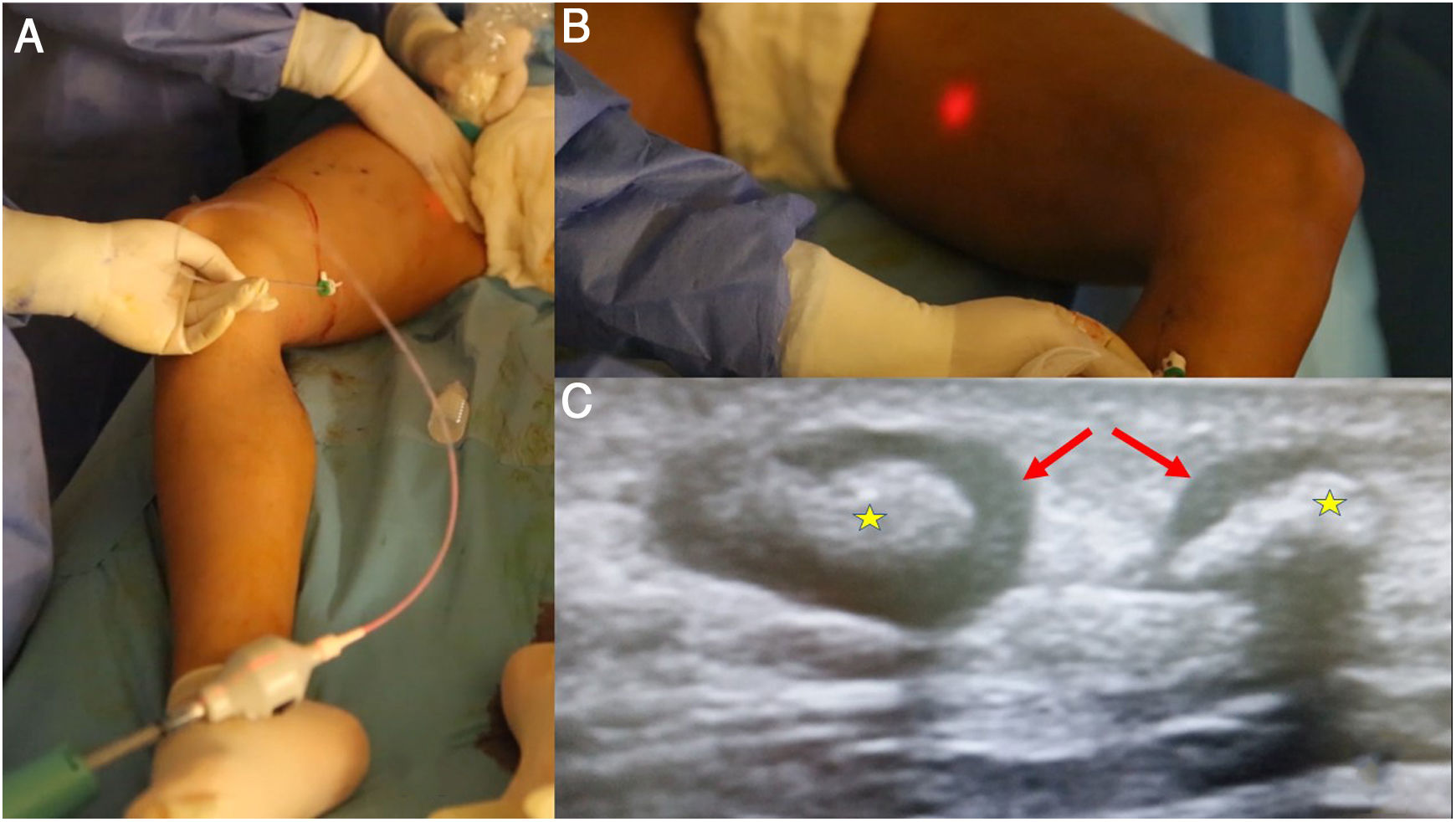

Cyanoacrylate occlusionAlthough cyanoacrylate has been widely used by interventional radiologists and neuroradiologists as an embolisation method since the 1980s, it was not until relatively recently that it began to be used in the treatment of varicose veins.

Since the approval and CE marking of the first saphenous vein occlusion system using a specially formulated adhesive (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) in autumn 2011, many patients have benefited from this technique.

This formulation was intended to satisfy two objectives: that the consistency of the glue after polymerising would be less hard and more flexible to avoid a foreign-body sensation, and that the polymerisation time (solidification) would enable the product to move far enough away from the catheter tip, without risk of migrating.

Like MOCA techniques, it does not require the use of tumescent anaesthesia.

As a distinguishing and exclusive factor, by causing both vein walls to join immediately, elastic compression stockings need not be used following the procedure.

The procedure is also performed with minimal local anaesthesia at the entry point. Ultrasound guidance is used to access and navigate the saphenous vein up to 2−3 cm from the confluence with the deep venous system. The different systems available consist of a catheter and a dispensing gun. The VenaBlock® (Invamed Health, Ankara, Turkey) also has an LED light which allows the catheter tip to be monitored with the naked eye, except through large amounts of adipose tissue in the thighs (Fig. 9).

A) Among the saphenous trunk occlusion systems using cyanoacrylate, the most widely used one and the one with the longest history is VenaSeal®; however, several devices that share the same philosophy have recently appeared. They consist of a catheter, with certain characteristics to minimise the risk of adhesion to the vein, and a dispensing gun. B) The Venablock® device, for its part, is equipped with an LED light on its tip that allows direct visualisation of the route in certain cases. C) There is the possibility of treating tortuous tributary branches by direct puncture and injection of cyanoacrylate. A follow-up ultrasound after a few weeks shows inflammatory signs (which will contribute to the occlusion of the vein) with significant thickening of the walls (arrows) and occupation of the lumen with material that causes acoustic shadowing (stars).

It is extremely important to apply very strong compression on the ablation trajectory, as although the polymerisation of the glue causes a momentary increase in temperature to about 45 °C–50 °C, this is not the mechanism of action, but rather an occlusion of the vascular lumen by adhesion of its walls.

In terms of outcomes, in the case of the VenaSeal® Closure system (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States), which is the most widely marketed system with the most available scientific literature, the occlusion rates reported are 99.6% at six and 12 months; similar to or even higher than those reported with the use of RF and laser techniques.14,15 One single-centre retrospective study reported occlusion rates of 96.4% at six years.16

In addition to cyanoacrylate ablation or occlusion of the saphenous veins through a catheter, it is also possible to perform direct puncture and injection of the glue to treat tributary branches or perforator veins. Some companies have a product specially designed for this purpose, with modified and adaptable polymerisation times, depending on the dilution in dextrose (VeinOFF®, Invamed Health, Ankara, Turkey). The major disadvantage of this procedure, however, is that the usual aspiration method cannot be used to check the intravascular position of the needle, as an influx of blood would cause the product to polymerise immediately.

Chemical ablation with sclerotherapySclerotherapy consists of injecting an irritating chemical into the lumen of the vein in order to cause an inflammatory reaction primarily in the endothelium and the subsequent fibrous obliteration of the treated segment of the vein. The aim is to cause irreversible but controlled and low-intensity damage to the wall in the form of varicophlebitis.17

The goal is not to cause venous occlusion at the expense of segments with varicothrombosis, as the thrombotic component is at risk of rechannelling and returning to the previous state.

Therefore, only injection of the sclerosant in the form of a foam will be considered, as its action on the veins has long been known to be much greater than the sclerosant in the form of a liquid. The sclerosant in liquid form has been relegated to use in telangiectasias and reticular veins (where veins are larger than 4 mm, the dilution of the sclerosant renders it ineffective).

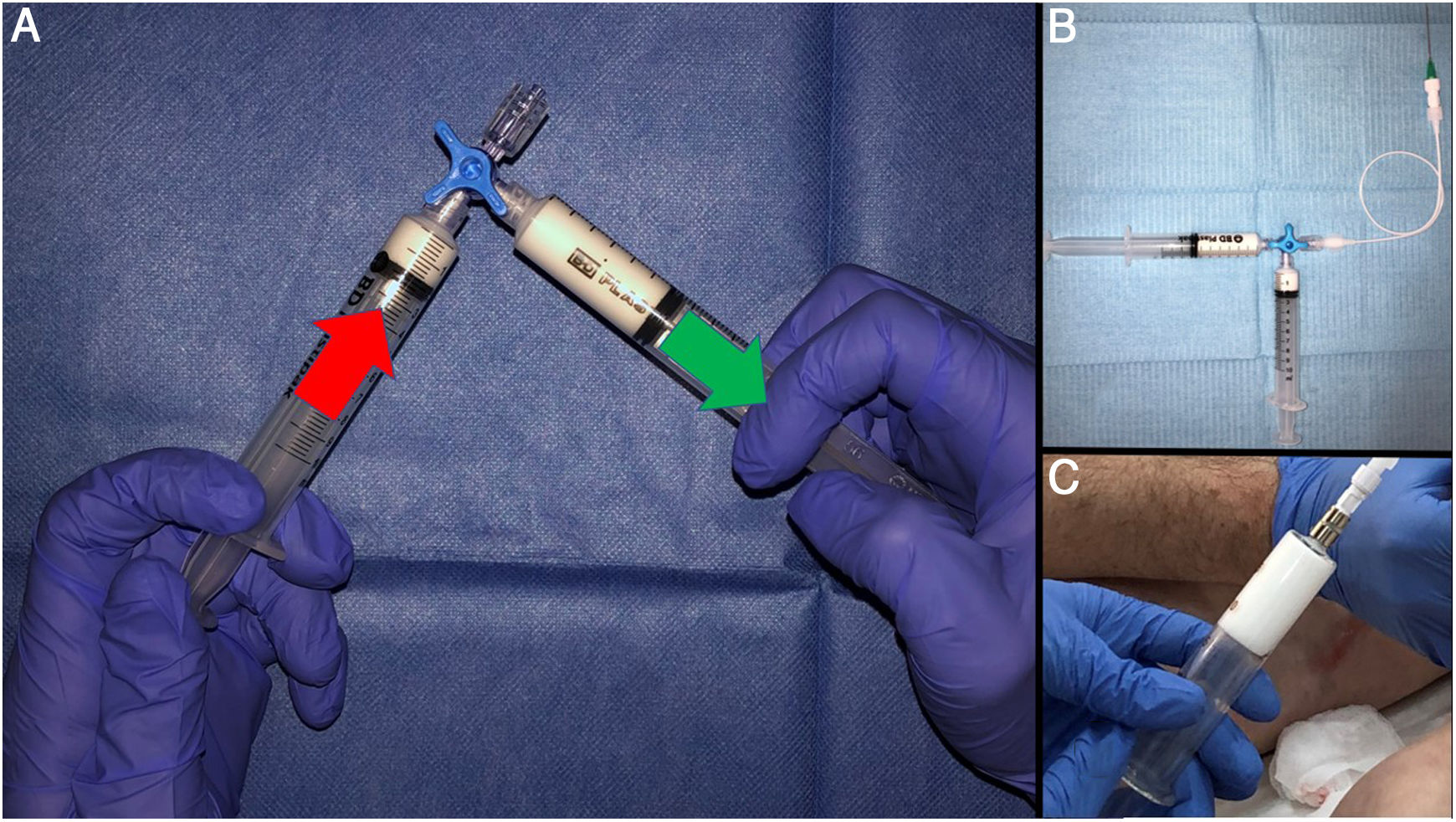

In 1995, Juan Cabrera, a vascular surgeon from Granada, Spain, reported excellent results in the treatment of truncal varicose veins with his patented microfoam formula.18 Later, in 2000, Lorenzo Tessari reported what is probably the simplest and most widely used method of foam production19 (Fig. 10).

A) The technique reported by Tessari consists of forceful transfer from one syringe to another through a three-way valve. The turbulence created forms the foam. Around 20 transfers yield a foam of a quality considered to be standard. If Luer lock syringes are not used, it is recommended that they be supported on the surface of a table or even against the abdomen. The valve can be partially closed to improve the quality of the foam. This has been found to produce smaller bubbles. B) It is advisable to use equipment with as little lubricant as possible. The BD syringes in the example have less than 0.25 mg/cm2 of silicone oil. Filters (Sterifix®, BRAUN, 5 microns) can be added to create a more uniform bubble size and thus reduce the coalescence phenomenon. C) Glass syringes represent better storage conditions for the foam.

However, there is still a great deal of technical variability in the performance, and therefore the outcomes, of ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy. Meta-analyses of ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy do not support the comparison with saphenectomy and thermal ablation techniques for the treatment of the saphenous veins.20 Even so, in terms of simplicity, low cost, safety and good overall results, it has no competition.

Without delving too deeply, currently in Spain there are two detergent-type sclerosing agents suitable for use in foam: Etoxiesclerol© [Aethoxysklerol] (Lauromacrogol 400, also known as polidocanol) and, more recently, Veinfibro© [Fibro-Vein] (sodium tetradecyl sulphate [STS]). Both have similar characteristics and methods, although Veinfibro© is reported to have a greater range of action, being 1.5–2 times more potent than Etoxisclerol© at the same concentration.21

The success of ultrasound-guided foam therapy stems from a combination of the quality of the sclerosing foam that is used and how it is distributed. In the latter regard, mastery of the ultrasound-guided puncture technique is of vital importance. The effect of the sclerosing foam on the vein wall varies according to the contact time with the endothelium and the concentration of the product used. These two parameters must be taken into account in order to select the concentration of sclerosing agent in relation to the size and location of the veins to be treated.

As a guideline, there are recommended doses of sclerosing foam, adjusted for the size of the varicose vein to be treated (e.g. for tributary varicose veins do not exceed 2% polidocanol or 1% sodium tetradecyl sulfate). These doses suggested in the European guidelines on sclerotherapy are generic22 and probably much higher than those most healthcare professionals would use. There are methods for optimising the sclerosing action without modifying the concentration of the product, such as elevation of the limb or use of tourniquets.

Therefore, as general concepts, "good distribution can make up for a bad foam", and, likewise, a good foam that is poorly distributed can be ineffective and even cause complications from excessive sclerosing action.

A detailed explanation of foam preparation is beyond the scope of this article, but some practical points to remember are as follows:

- •

In general, the smaller the bubble, the more stable the foam (law of Laplace), and the more stable the foam, the more capable it is of displacing the blood and the longer the contact time with the endothelium.

- •

The generally recommended fluid-to-gas ratio is 1:4. There is a minimum gaseous fraction for foam to behave like a solid and be better able to displace blood, which is 0.64 (64% of the volume of the foam must be composed of gas). In everyday practice, the amount of gas must be adapted according to the concentration of the sclerosing agent in order to avoid preparing foams which are too liquid or too dry.

- •

Once the foam has been prepared, it must be injected within 60−120 s.

- •

Silicone-free material should be used where possible, as this will break down the foam in the system. Similarly, adding filters to a system promotes a homogeneous foam size, which minimises the physical phenomenon of coalescence and makes the foam more stable.

Although very safe, sclerotherapy is not without complications (adverse reactions to the sclerosing agent, skin necrosis, neurological symptoms, etc). A detailed study of its complications prior to its generalised use is recommended.

TechniqueThe French National Agency for Accreditation and Evaluation in Health (ANAES) recommends the following phases for the procedure23:

- 1

Ultrasound assessment of the segment to be treated.

- 2

Ultrasound-guided venipuncture.

- 3

Verification of position and injection of the drug with ultrasound monitoring.

- 4

Post-injection follow-up ultrasound with verification of venous spasm and distribution.

- 1

Ultrasound assessment of the segment to be treated, whether a saphenous vein or tributary branches. As previously discussed, good treatment planning is vitally important. Before puncture (which is ideally cranial to caudal) is done, the puncture sites must be chosen, as foam expansion precludes doing so afterwards. It is important to choose deep puncture sites wherever possible, as it must be remembered that the injection site is the site of highest concentration and longest action time of the sclerosing agent. The ultrasound assessment also enables arterioles to be located and avoided, since puncturing and injecting sclerosing agent into such vessels would be disastrous.

- 2

Ultrasound-guided venipuncture. Some healthcare professionals prefer the wing grips on Luer lock syringes. Others, however, use extension sets connected to 22 G–25 G needles or even direct puncture with a syringe.

- 3

Verification of position and injection of the drug with ultrasound monitoring. Once the vein is punctured, the intravascular position must be confirmed by aspirating before injecting (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.A) Treatment planning begins with a proper ultrasound assessment. This patient has an intrafascial segment of the accessory saphenous vein prior to its subcutaneous route. This enables higher concentrations to be used proximally, thus minimising the risk of skin complications. B) Always puncture from proximal to distal so that foam distribution does not preclude access to other points along the venous pathway. Blood aspiration to confirm intravenous position. C) Injections in more distal and superficial points with adaptation of the concentrations of the sclerosant. The more superficial the point, the lower the sclerosant concentration.

- 4

When aspirating, no blood may be allowed to enter the syringe, as contact with even a small amount of blood on the part of the foam is enough to deactivate it within a few seconds through plasma proteins.24

- 5

Post-injection follow-up ultrasound with verification of venous spasm and distribution. Good distribution of foam in segments which are not too far from the puncture point, using the milking technique (distributing the foam with the ultrasound transducer), will optimise the results. In addition, the pressure of the transducer itself can be used to block the foam from passing through perforator veins or the junction.

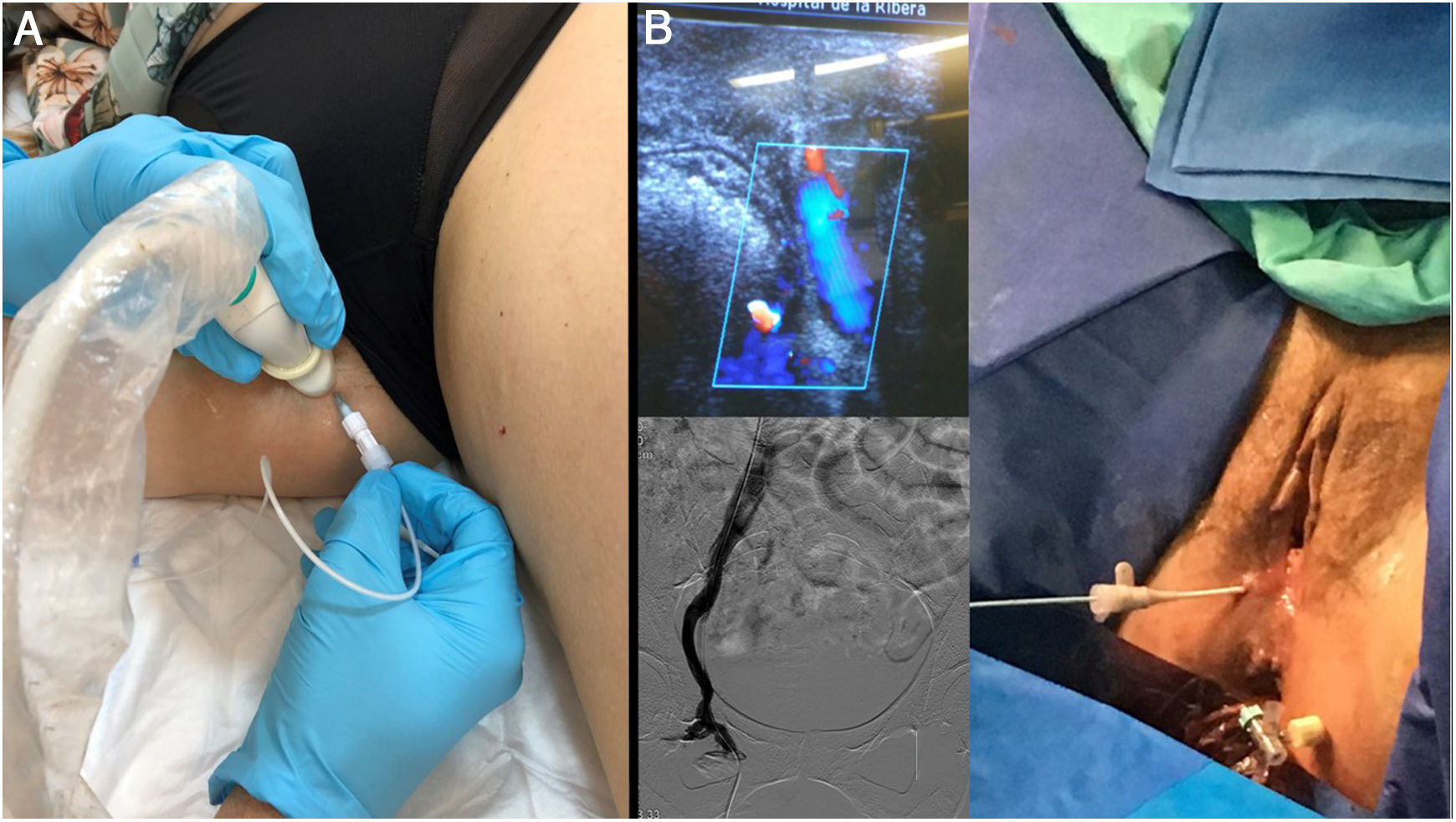

Although the ideal management of gonadal varicose veins and their clinical version, pelvic congestive syndrome, is through venography and selective embolisation of the refluxing pelvic segments, it is also possible to treat incompetent segments coming from the pelvis (points of pelvic leak) using ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy. Likewise, ultrasound is an essential tool for catheterising difficult-to-access veins via pudendal access (Fig. 12).

A) Shunts of pelvic origin are very common, and can be treated with no need for embolisation of pelvic varices, especially when the patient lacks symptoms of pelvic congestion and the end goal is purely to manage reflux towards the legs. B) If, due to previous embolisations, it is not possible to access the distal pelvic varicose plexuses by the conventional route, this figure shows an alternative ultrasound access route through the pudendal vein in Alcok's canal (leak point P), which even allows catheterisation. From this approach, it is possible to embolise proximal segments through a catheter and/or perform direct foam injection.

The proliferation of intravenous techniques for the treatment of varicose veins in the legs, especially affecting the saphenous veins, can seem overwhelming. This article has sought to offer an overview and a brief outline of some of them.

The main ideas we would like to highlight are that, currently, thanks to all of these techniques, it is not necessary to resort to conventional surgery for the treatment of leg varicose veins and that these techniques are gradually going to supplant the surgical option due to their lower associated morbidity. They may cost more, but this is debatable, as they also avoid the use of conventional operating theatres, hospital admissions and sick leave.

Currently, devices for saphenous vein occlusion appear to show similarly effectiveness. For this reason, the choice of a specific technique or a combination of techniques is considered the lesser issue, compared to the development of a safe and effective treatment strategy.

However, one consideration alone can make the difference when it comes to achieving good results, and that is full mastery of both diagnostic and interventional ultrasound.

FundingNo funding.

Conflicts of interestProctor and consultant for Merit Medical, Cook, Terumo and Logsa Endomedical S.L.

I would like to warmly thank my colleagues in the angiology and vascular surgery department and to my colleagues in vascular radiology for their support and help over the years.

Please cite this article as: Cosín Sales O. Serie ecografía intervencionista: Intervencionismo venoso guiado por ecografía. Radiología. 2022;64:89–99.