The purpose of this study was to investigate perspectives held by radiologists on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in their day-to-day work and to identify factors limiting its routine implementation.

Materials and methodsSpanish board-certified radiologists and trainees completed an online survey of 21 questions on general information and communications technology (ICT) and AI in radiology. Analysis was carried out for the subgroups of gender, age, and professional experience. Associations with a p-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 102 radiologists and trainees completed the questionnaire. No se observaron diferencias estadísticas significativas entre los grupos de sexo. A significant difference was detected in ICT and AI knowledge between age groups, with participants under 40 and those between 40 and 55 years old demonstrating better ICT knowledge (p < 0.01). The survey results revealed that 77.4% of participants believed that AI represents an opportunity for the radiology profession in the future, while 9.8% believed it would have no impact. Three main practical application areas for AI in radiology were proposed: in screening (23.36%), in image interpretation and reporting (21.17%), and in the requesting of imaging and patient scheduling (14.6%). The biggest concern among the surveyed population was the potential increase in workload.

ConclusionsA positive attitude toward AI was observed among Spanish radiologists, with the majority believing that AI could offer opportunities for the radiology profession in the near future. AI training programmes may further improve its acceptance among professionals.

El propósito de este estudio fue investigar el punto de vista de los radiólogos sobre el uso de la inteligencia artificial (IA) en su práctica diaria e identificar los factores que limitan su implementación sistemática.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó una encuesta por Internet entre radiólogos y residentes de radiología españoles, con 21 preguntas sobre los conocimientos generales de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) y de la IA en radiología. Se realizaron análisis de subgrupos por sexo, edad y experiencia profesional. Las asociaciones con un valor p < 0,05 se consideraron significativas.

ResultadosUn total de 102 radiólogos y residentes respondieron al cuestionario. No se observaron diferencias estadísticas significativas entre los grupos de edad o género. Se detectó una diferencia significativa en el conocimiento de las TIC y la IA entre los grupos de edad, siendo los participantes menores de 40 años y los de entre 40 y 55 años los que tenían un mejor conocimiento de las TIC (p < 0,01). Los resultados de la encuesta mostraron que el 77,45% de los participantes creía que la IA representa una oportunidad para la profesión radiológica en el futuro, mientras que el 9,80% creía que no tendrá ningún impacto. Se sugirieron tres áreas principales de aplicación práctica de la AI en radiología: en el cribado (23,36%), en la interpretación de imágenes y la elaboración de informes (21,17%) y en la solicitud de las pruebas de imagen y la programación de pacientes (14,60%). La mayor preocupación entre la población encuestada era el posible aumento de la carga de trabajo.

ConclusionesSe encontró una actitud positiva entre los radiólogos españoles hacia la IA, donde la mayoría de los encuestados contestó que la IA supondría una oportunidad para la profesión en un futuro próximo. La implementación de programas de formación en AI podría mejorar su aceptación entre los profesionales.

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have shown the potential to transform healthcare systems and medical imaging in the coming years.1–3 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has cleared more than 200 AI software that can be used in several clinical settings of the radiology workflow.4

In particular, the development of deep learning (DL), a specific subtype of AI techniques, marked a turning point in the history of AI applied to object recognition, as it has proved that automated image analysis could exceed human abilities. This historical achievement dates to 2012 when Krizhevsky and colleagues won the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge with AlexNet, a convolutional neural network (CNN).5 Implementing AI in medical imaging is considered a potential way to address one of the greatest challenges that radiology departments are facing worldwide, which is the progressive increase in workload that it has experienced in recent decades.6 As the amount of clinically valuable information present in medical imaging has increased significantly in the last decade, radiologists have found progressively challenging to manage and analyse these complex datasets.7 These profound transformations have led to an extremely time-consuming analysis of medical images, which is often incompatible with routine activity.8

Although AI has the potential to overcome many of the problems previously mentioned, there is still a low acceptance by many radiologists to adopt these systems into clinical practice.9

To date, only a few studies have considered how the acceptance or expectations of AI vary among different age groups of radiologists and radiology residents.10–12 Our survey was carried out when AI software was not only available on the market but also accessible to many professionals.4 The current study aims to better understand radiologists' knowledge and attitudes towards information and communication technology (ICT) and AI. An ad hoc survey was developed to investigate radiologists' acceptance of AI in their daily activities, their awareness of available technologies, their willingness to learn more, and their perception of AI as either a threat or as a means to improve the quality of work in radiology.

Materials and methodsQuestionnaireAn ad hoc questionnaire of 21 questions about AI in radiology was developed by the research team. A web-based survey using Google Forms (Google LLC) was created and the link, along with a short description of the scope of the survey was shared by email to coauthors’ colleagues, through the newsletter of the Catalan Society of Radiologists, and on the professional social media platform LinkedIn. Answers were collected anonymously from the 25th of October 2021 to the 27th of January 2022. The study was a voluntary survey among radiology professionals that did not involve collecting any health or personal information and all data were handled anonymously; therefore, institutional review board approval was not necessary. The survey included questions on demographics (age, gender, degree, and years of professional experience), respondents' awareness, perception, and attitudes towards AI in specific settings (see Supplementary Material, Survey Design for details). Questions were formulated in a multiple-choice or open–ended format.

Study participantsOnly board-certified radiologists and trainees in radiology working in Spain were intended to answer the survey. Radiographers and other healthcare professionals were excluded.

Statistical analysisDescription of qualitative data was carried out with absolute frequencies and corresponding percentages. Response percentages were estimated using 95% confidence intervals. A bivariate analysis was carried out using the Chi-square test to compare the differences between the different categories of the qualitative variables or Fisher's exact test for groups with 5 people or less. Subgroup analyses were performed by gender, age, and professional experience. Associations with a p-value <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed with the Stata ® version 14.2 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

The manuscript follows the Equator Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guide.13

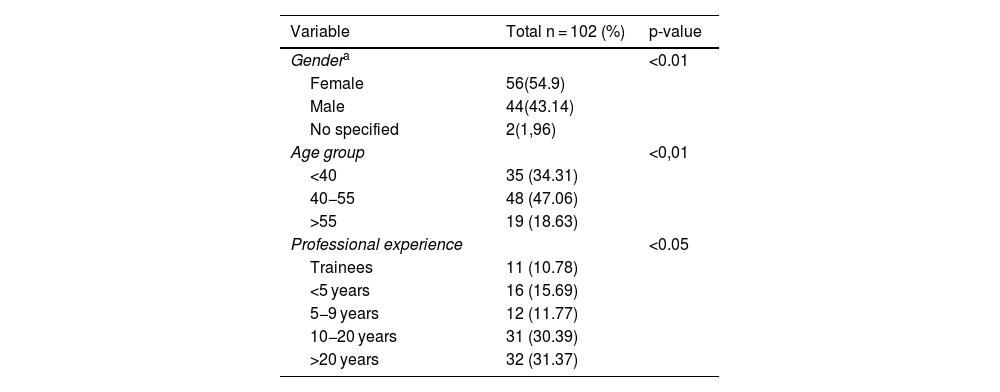

ResultsDemographicsA total of 103 imaging professionals completed the questionnaire. One participant was excluded because he/she declared to be a radiographer and did not meet the inclusion criteria, which specified that only radiologists or radiologist trainees were eligible. Baseline demographic characteristics of 102 survey respondents are presented in Table 1 (supplementary material). The results show that 34.31% were under 40, 47.06% were in the 40–55 age group, and 18.63% were over 55 years old. Radiologist trainees accounted for a small percentage of the respondents (10.78%), while the majority of them had work experience of 10−20 years (30.39%) or more than 20 years (31.37%). There was a slight predominance of females (n = 56) compared to males (n = 44), with no statistical differences. The two participants who preferred not to specify their gender were excluded when gender subgroup analysis for different variables was performed.

Demographic characteristics of 102 radiologists and radiology residents participated in the study.

| Variable | Total n = 102 (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Gendera | <0.01 | |

| Female | 56(54.9) | |

| Male | 44(43.14) | |

| No specified | 2(1,96) | |

| Age group | <0,01 | |

| <40 | 35 (34.31) | |

| 40−55 | 48 (47.06) | |

| >55 | 19 (18.63) | |

| Professional experience | <0.05 | |

| Trainees | 11 (10.78) | |

| <5 years | 16 (15.69) | |

| 5−9 years | 12 (11.77) | |

| 10−20 years | 31 (30.39) | |

| >20 years | 32 (31.37) |

Chi-Square test was used for the p-value. Tests were performed at the two-sided 0.05 significance level.

The study revealed that the participants' self-perception of their ICT knowledge was evenly distributed among elementary, intermediate, intermediate/advanced, and advanced levels, with no significant differences among the groups. However, there was a significant difference in ICT knowledge between age groups, with participants under 40 and those between 40 and 55 years old demonstrating better ICT knowledge. The study also found that specialists with more than 10 years of experience had intermediate to intermediate-advanced knowledge of ICTs, while only 11.7% of those surveyed reported having advanced ICT knowledge, with no significant differences between the different experience groups.

According to the survey outcomes, 49.02% of the participants believed they had a clear understanding of AI and its possible future effects on work practice. A small proportion of respondents, accounting for 11.76% stated they had a limited understanding of AI but were interested in learning more, while 38.2% claimed they had a general idea of AI but lacked a comprehensive understanding of its possible applications and benefits in their daily practice. Statistically significant differences were observed among age groups (p=<0.01) and professional experience (p < 0.01).

AI-specific knowledgeThe investigation revealed that 58.82% of the participants stated that they were able to distinguish among the different concepts of AI, machine learning (ML), and DL, with significant differences based on age, with participants between 40 and 55 years old being the most knowledgeable. There were significant differences based on age, but not on gender or professional experience, with 88.24% of the participants unable to distinguish between "Narrow or Weak" and "General or Strong" AI. Among the surveyed participants, 62.75% acknowledged they were able to define the concept of Radiomics, with significant differences based on age and professional experience, but not gender. The youngest radiologists, those under 55 years old, demonstrated a better ability to differentiate between “Narrow or Weak” versus “General or Strong AI”.

More than two thirds of the participants (68.63%) had never heard of the Python programming language, and there were no significant differences in understanding technical concepts related to AI based on age or professional experience. However, there were significant differences in understanding based on gender, with women showing less knowledge. In terms of understanding the term "Black box" in AI, there were no significant differences based on age or professional experience, but there were statistical differences based on gender, with women demonstrating less understanding (Table 2 in the supplementary material).

Self-reported perceptions of ICT or AI and objective questions on conceptual understanding of AI.

| Total | Age groups | Gendera | Professional Experience | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 102 | <40 years | 40−55 years | >55 years | Male | Female | Trainee | <5 years | 5–9 years | 10–20 years | >20 years | p-value | |||

| n = 35 | n = 48 | n = 19 | p-value | n = 44 | n = 56 | p-value | n = 11 | n = 16 | n = 12 | n = 31 | n = 32 | |||

| Self perception ICT knowledge | 0.44425 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.159 | ||||||||||

| Elementary ICT skills | 27(26.47) | 14(40) | 13(27.08) | 0(0) | 4(9.09) | 23(41.07) | 5(45.46) | 5(31.25) | 5(41.67) | 9(29.03) | 3(9.38) | |||

| Intermediate | 40 (39.22) | 11(31.43) | 17(35.42) | 12(63.16) | 16(36.36) | 23(41.07) | 3(27.27) | 6(37.50) | 4(33.33) | 10(32.26) | 17(53.12) | |||

| Intermediate/advanced | 23 (22.55) | 3(8.57) | 14(29.17) | 23(31.58) | 15(39.09) | 8(14.29) | 1(9.09) | 2(12.50) | 1(8.33) | 9(29.03 | 10(31.25) | |||

| Advanced users | 12 (11.76) | 7(20) | 4(8.33) | 1(5.26) | 9(20.45) | 2(3.57) | 2(18.18) | 3(18.75) | 2(16.67) | 3(9.68) | 2(6.25) | |||

| Self perception about IA | 0.48838 | 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.003 | ||||||||||

| No knowledge and no interest | 1(0.8) | 0(0.0) | 1(2.08) | 0(0.0) | 1(100) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 1(3.12) | |||

| Confused but interested in learning more | 12(11.76) | 11(31.43) | 1(2.08) | 0(0.0) | 2(16.67) | 10(83.35) | 4(36.36) | 5(31.25) | 2(16.67) | 1(3.23) | 0(0.0) | |||

| General idea of AI but lacked a good understanding | 39(38.24) | 11(31.43) | 22(45.84) | 6(31.58) | 13(34.21) | 25(65.79) | 4(36.36) | 4(25.0) | 4(33.3) | 17(54.83) | 10(31.25) | |||

| Clear understanding | 50(49.02) | 13(37.14) | 24(50.0) | 13(68.42) | 28(57.12) | 21(42.86) | 3(27.28) | 7(43.75) | 6(50.0) | 13(41.94) | 21(65.63) | |||

| Heard about Phyton | 0.13378 | 0.542 | 0.000 | 0.642 | ||||||||||

| No | 70(68.63) | 25(71.43) | 34(70.83) | 11(57.89) | 22(50.00) | 48(85.71) | 8(72.73) | 13(81.25) | 8(66,67) | 22(70.97) | 19(59.38) | |||

| Yes | 32(31.37) | 10(28,57) | 14(21.17) | 8(42.11) | 22(50.00) | 8(14.29) | 3(27.27) | 3(18.75) | 4(33.33) | 9(29.03) | 13(40.62) | |||

| Know what Black Box means for IA | 0.02465 | 0.145 | 0.001 | 0.423 | ||||||||||

| No | 74(72.55) | 29(82.86) | 34(70.83) | 11(57.89) | 25(56.82) | 48(85.71) | 9(81.82) | 13(81.25) | 9(75.00) | 24(77.42) | 19(59.38) | |||

| Yes | 24(27.45) | 6(17.14) | 14(29.17) | 8(42.11) | 19(43.18) | 8(14.29) | 2(18.18) | 3(18.75) | 3(25.00) | 7(22.58) | 13(40.62) | |||

| Differences between ML and DL | 0.99979 | 0.030 | 0.227 | 0.195 | ||||||||||

| No | 42(41.18) | 20(57.14) | 18(37.05) | 4(21.05) | 15(34.09) | 26(46.43) | 7(63.64) | 6(37.5) | 7(58.33) | 13(41.94) | 9(28.12) | |||

| Yes | 60(58.82) | 15(42.86) | 30(62.5) | 15(78.95) | 29(65.91) | 30(53.57) | 4(36.36) | 10(62.5) | 5(41.67) | 18(58.06) | 23(71.88) | |||

| Differences between Narrow/General IA | 0.00000 | 0.030 | 0.213 | 0.195 | ||||||||||

| No | 90(88.24) | 20(57.14) | 18(37.5) | 4(21.05) | 15(34.09) | 26(46.43) | 7(63.64) | 6(37.5) | 7(58.33) | 13(41.93) | 9(29.03) | |||

| Yes | 12(11.76) | 15(42.86) | 30(62.5) | 15(78.95) | 29(65.91) | 30(53.57) | 4(36.36) | 10(62.5) | 5(41.67) | 18(58.07) | 23(71.87) | |||

| Radiomic definition | 0.9575 | 0.031 | 0.074 | 0.025 | ||||||||||

| No | 38(37.25) | 19(54.29) | 15(31.25) | 4(21.05) | 12(27.27) | 25(44.64) | 8(72.73) | 6(37.5) | 7(58.33) | 9(29.03) | 8(25.00) | |||

| Yes | 64(62.75) | 16(45.71) | 33(68.75) | 15(78.95) | 32(72.73) | 31(55.36) | 3(27.27) | 10(62.5) | 5(41.67) | 22(70.97) | 24(75.00) |

Chi-Square test was used for the p-value. Fisher's exact has been used when absolute frequencies are below 5. Tests were performed at the two-sided 0.05 significance level.

The survey results indicated that 77.45% of participants view AI as an opportunity for the radiology profession, while 9.80% believe it will have no impact, and 7.85% see it as a threat in the next 10 years. There were no significant differences in these views based on age groups, professional experience, or gender. Regarding the future impact of AI on radiology, most respondents anticipated a significant (40.20%) or radical transformation (33.33%), with none choosing the option of no change (p < 0.05). There were also no statistical differences based on age groups, gender, or professional experience.

Respondents had varied opinions on how AI will affect the security of personal data and health information. A minority (1.96%) believed it would have no impact, while a larger portion, (30.39%) anticipated a significant impact, and another 26.47% foresaw a radical impact on these data (p < 0.05). The respondents' views regarding expectations related to the implementation of AI in Radiology and its consequences are presented in Table 3 of the supplementary material.

Perspectives and attitudes toward AI in radiology and its consequences.

| Total | Age groups | Gendera | Professional experience | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 102 | <40 years | 40−55 years | >55 years | Male | Female | Trainee | <5 years | 5–9 years | 10–20 years | >20 years | ||||

| n = 35 | n = 48 | n = 19 | p-value | n = 44 | n = 56 | p-value | n = 11 | n = 16 | n = 12 | n = 31 | n = 32 | p-value | ||

| Implications of introducing AI in Radiology | 0.000 | 0.416 | 0.644 | 0.069 | ||||||||||

| Threat in short term <5 years | 5(4.90) | 3(8.57) | 2(4.17) | 0(0.00) | 2(4.55) | 3(5.36) | 1(9.09) | 2(12.50) | 1(8.33) | 0(0.00) | 1(3.12) | |||

| Threat in long term >10 years | 8(7.85) | 5(14.29) | 3(6.25) | 0(0.00) | 5(11.36) | 3(5.36) | 2(18.18) | 0(0.00) | 2(16.67) | 3(9.67) | 1(3.12) | |||

| Indifferent effects | 10(9.80) | 4(11.43) | 4(8.33) | 2(10.53) | 5(11.36) | 5(8.93) | 1(9.09) | 2(12.50) | 3(25.00) | 1(3.23) | 3(9.38) | |||

| Opportunity | 79(77.45) | 23(65.71) | 39(81.25) | 17(89.47) | 32(72.73) | 45(80.35) | 7(63.64) | 12(75.00) | 6(50.00) | 27(87.10) | 27(84.38) | |||

| Profession change | 0.0157 | 0.941 | 0.819 | 0.491 | ||||||||||

| 1 (no change) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | |||

| 2 | 2(1.96) | 1(2.86) | 1(2.08) | 0(0.00) | 1(2.27) | 1(1.79) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 1(8.33) | 0(0.00) | 1(3.12) | |||

| 3 | 25(24.51) | 11(31.43) | 11(22.92) | 3(15.79) | 9(20.45) | 15(26.79) | 3(27.27) | 6(37.50) | 4(33.34) | 7(22.58) | 5(15.62) | |||

| 4 | 41(40.20) | 16(45.71) | 18(37.50) | 7(36.84) | 17(38.64) | 23(41.02) | 5(45.46) | 8(50.0) | 4(33.33) | 11(35.48) | 13(40.63) | |||

| 5 ( maximun change) | 34(33.33) | 7(20.00) | 18(37.50) | 9(47.37) | 17(38.64) | 17(30.31) | 3(27.27) | 2(12.50) | 3(25.00) | 13(41.94) | 13(40.63) | |||

| AI effect on protection of personal - health data | 0.02051 | 50.941 | 0.696 | 0.966 | ||||||||||

| 1 (no effect) | 2(1.96) | 0(0.00) | 1(2.08) | 1(5.26) | 1(2.27) | 1( 1.79 ) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 1(3.23) | 1(3.12) | |||

| 2 | 11(10.79) | 4(11.43) | 6(12.50) | 1(5.26) | 6( 13.64) | 5(8.93) | 1(9.09) | 3(18.75) | 1(8.33) | 4(12.90) | 2(6.25) | |||

| 3 | 31(30.39) | 11(31.43) | 13(27.08) | 7(36.85) | 10( 22.73) | 20(35.71) | 2(18.18) | 6(37.50) | 3(25.00) | 8(25.81) | 12(37.50) | |||

| 4 | 31(30.39) | 11(31.43) | 14(29.17) | 6(31.58) | 15(34.09) | 16(28.57) | 5(45.46) | 3(18.75) | 5(41.67) | 8(25.81) | 10(31.25) | |||

| 5 (maximum change) | 27(26.47) | 9(25.71) | 14(29.17) | 4(21.05) | 12(27.27) | 14(25.00) | 3(27.27) | 4(25.00) | 3(25.00) | 10(32.25) | 7(21.88) | |||

| Negative legal consequences for radiologists | 0.02811 | 0.962 | 0.509 | 0.136 | ||||||||||

| No | 73(72.28) | 24(70.59) | 35(72.92) | 14(73.68) | 30(68.18) | 41(74.55) | 5(50.00) | 15(93.75) | 8(66.67) | 23(74.19) | 22(68.75) | |||

| Yes | 28(27.72) | 10(29.41) | 13(27.08) | 5(26.32) | 14(31.82) | 14(25.45) | 5(50.00) | 1(6.25) | 4(33.33) | 8(25.81) | 10(31.25) | |||

Chi-Square test was used for the p-value. Fisher's exact has been used when absolute frequencies are below 5. Tests were performed at the two-sided 0.05 significance level.

Regarding the implementation of AI and its potential negative consequences in legal terms for radiologists, the majority of participants believed that AI would not negatively impact them. Out of the 28 participants who believed radiologists would face new legal repercussions due to the introduction of AI, 10 thought it might be due to increased legal obligations, 4 participants cited inadequacies in current legislation, and 1 participant mentioned limitations in the diagnostic accuracy of AI. However, two respondents attributed the legal repercussions to the loss of the radiologist's decision-making autonomy (p < 0.05).

In relation to the issue of the privacy of patients' personal and health data, only 2 out of 102 respondents (1.96%) believed that the introduction of artificial intelligence tools will have no impact on them. In contrast, the vast majority of survey respondents (56.86%) stated that it might have a significant or even substantial impact on the protection of such data.

The open question asking about three possible practical applications of AI in radiology received a total of 137 responses. Most participants suggested using AI as a tool for screening different pathologies (23.36%), followed by image interpretation and reporting (21.17%), imaging order and patient scheduling (14.60%), precision medicine (11.68%), radiomics (8.76%), follow-up studies (7.30%), image acquisition (5.8%), outcome and treatment planning (4.38%), and image post-processing (2.92%).

Fears and doubts about using AIThe open question about fears, needs, or expectations regarding the future of radiology revealed diverse reasons why professionals are worried about the prospects of their jobs. The major concern among the surveyed population was the steady increase in daily workload (24.14%), while other concerns included keeping up to date with innovations and advancements in medical imaging (9.48%), the risk of missing the correct diagnosis or making the wrong diagnosis (7.76% and 8.62%, respectively), improving workflow and diagnostic accuracy, familiarising with technological advancements, and choosing the appropriate imaging protocol and treatment/management for patients (7.76% each). Only a few respondents mentioned AI as a possible threat.

Learning AIRespondents' views on the attitudes towards learning about AI and inclusion in the residency curriculum are detailed in Table 4 of the supplementary material. Most of the respondents (68.62%) answered that they would like to learn more about AI applied to radiology, compared to 13.73% who were not interested in doing so and 17.65% who were unsure. Most of the affirmative answers were given by participants in the younger age groups, but no significant differences were found among all age groups (p = 0.80), professional experience (p = 0.74), or gender (p = 0.78). In addition, according to the vast majority of the respondents (92.16%) specific training in AI should be included in the curriculum for radiology residents with no differences between age groups (p = 0.80) or gender (p = 0.23) but with a significant difference with professional experience (p < 0.05). Among those 54 answers of participants willing to delve into more specific aspects of AI, the majority expressed an interest in learning either its basic applications (53.70%) or its applications in specific fields of radiology (27.78%). Respondents also showed interest in exploring the foreseen advantages and disadvantages, the feasibility of the implementation of AI in daily practice, and the consequences faced by the radiologist in the future in legal/ethical terms or from the economic point of view.

Willingness to learn and apply AI in radiology.

| Total | Age group | Gendera | Professional experience | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 40 | <40 year | 40−55 year | >55 year | Male | Female | Trainee | <5 year | 5-9 year | 10-20 yeary | >20 year | ||||

| N = 35 | N = 48 | N = 19 | p-value | N = 44 | N = 56 | p-value | N = 11 | N = 16 | N = 12 | N = 31 | N = 32 | p-value | ||

| Deepen knowledge in IA applied to Radiology | 1 | 0.799 | 0.782 | 0.742 | ||||||||||

| No | 14(13.73) | 6(17.14) | 6(12.50) | 2(10.53) | 5(11.36) | 8(14.29) | 1(9.09) | 4(25.00) | 3(25.00) | 2(6.45) | 4(12.50) | |||

| Yes | 70(68.62) | 25(71.43) | 32(66.67) | 13(68.42) | 32(72.73) | 37(66.07) | 8(72.73) | 10(62.50) | 8(66.67) | 22(70.97) | 22(68.75) | |||

| Maybe | 18(17.65) | 4(11.43) | 10(20.83) | 4(21.05) | 7(15.91) | 11(19.64) | 2(18.18) | 2(12.50) | 1(8.33) | 7(22.58) | 6(18.75) | |||

| IA introduced in resident curricula | 0 | 0.799 | 0.235 | 0.038 | ||||||||||

| No | 8(7.84) | 3(8.57) | 3(6.25) | 2(10.53) | 5(11.36) | 2(3.57) | 0(0.00) | 1(6.25) | 4(33.33) | 1(3.23) | 2(6.25) | |||

| Yes | 94(92.16) | 32(91.43) | 45(93.75) | 17(89.47) | 39(88.64) | 54(96.43) | 11(100.00) | 15(93.75) | 8(66.67) | 30(96.77) | 30(93.75) | |||

Chi-Square test was used for the p-value. Fisher's exact has been used when absolute frequencies are below 5. Tests were performed at the two-sided 0.05 significance level.

Our study is, to our knowledge, the second largest one conducted in Spain on the topic of AI among radiologists and trainees after the study of Eiroa et al. (2022), which was the first one in exploring the understanding of AI terminology and the need for structured AI training among Spanish professionals.10 Unlike Eiroa's study, our aim was to investigate the knowledge and attitudes about ICT and AI, specifically examining generational differences among baby boomers, generation X, and generation Y. Indeed, these generational cohorts possess distinct qualities influenced by advancements in technology and shifts in society.15

The gender distribution of the population that participated in our survey reflects a slight predominance of women in accordance with the latest Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica (SERAM) report on the presence of women in Radiology, where 54% of SERAM members are women.14 We categorised participants' ages into three groups based on generation brackets, as previously established.15 We intentionally divided participants into age groups to explore potential variations in knowledge and attitudes towards ICT and AI tools across different generational cohorts, including baby boomers (>55 years old), generation X (40−55 years old), and generation Y (<40 years old). This categorization was designed to assess whether distinct generational characteristics influenced the participants' perspectives on ICT and AI.

While no significant differences were found in these categories, the self-assessment of radiologists regarding AI and ICT expertise revealed noteworthy distinctions. Respondents in the oldest age group and with more work experience reported having a better understanding of ICT and AI; this may be attributed to practical experience through years of daily practice. Remarkably, more than forty-five percent of residents in radiology acknowledged that they only had a rudimentary knowledge of ICT and AI. This could be because residents or undergraduate programs in radiology did not require formal instruction on AI, a trend observed in similar surveys conducted in other countries.16–18

Additionally, significant differences also emerged when examining gender groups, with younger male radiologists starting to have a better understanding of ICT and AI than their female counterparts. This may be explained by the overall lower interest that women have shown in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) as reported by Sáinz et al.,19 a problem that raises concerns for the educational institutions and their curricula design.20 While the majority claimed knowledge of AI and ICT, none of the considered groups exhibited a good understanding of concepts like Python, Black box, strong/general versus narrow/weak AI, and Radiomics. This suggests that perceived ICT skills are likely subjective, depending on individuals' engagement in technology-based tasks. In contrast to common opinion, most of the respondents considered the introduction of AI in radiology as an opportunity for our profession, which is in agreement with results emerging in the survey conducted by J van Hoek et al., where the majority of the radiologists stated that AI should be used in Radiology.21 Nevertheless, in another study conducted by Huismal et al., participants showed an overall different disposition towards AI, as up to 38% of the surveyed population stated their fear that radiologists would be eventually replaced by AI in the future.11 The variation in attitudes toward AI between our study and others could be attributed to several factors. Firstly, our questionnaire targeted exclusively Spanish radiologists and trainees, whereas other surveys included a broader and potentially more diverse group of professionals from different geographical regions. Secondly, the timing of our survey likely influenced a more positive view of AI. The rapid escalation of AI technologies in recent times, impacting various societal sectors, including healthcare, may have contributed to a shift in professional perception. Lastly, we note that our survey avoided giving direct negative connotations (i.e. terms such as fears or threats) to the questions related to AI or mentioning the idea that AI would replace human expertise, leaving the participants to freely state their opinion from a neutral basis. In the question exploring how AI could change our profession, a great proportion of respondents (73,5%) answered that AI will have a disruptive or major effect on radiology, which agrees with the general perception of participants in other studies22,23 Considering that in the survey carried out by the European Society of Radiology (ESR) no agreement was found on how AI can impact in the labour market or workload,11 we decided not to investigate the specific subspecialties of radiology where major changes are expected. When asked about potential AI applications in clinical practice, most respondents favoured its use in screening for various pathologies (e.g., breast cancer, lung cancer), with some suggesting improvements in imaging order and patient scheduling. Notably, 37.9% of participants proposed AI as a tool to aid radiologists in avoiding repetitive and error-prone tasks, such as screening reading, or in reducing non-diagnostic responsibilities such as reviewing imaging orders and scheduling. Some studies have already assessed the potential application of AI software in specific screening scenarios, such as breast imaging. Ongoing studies are also exploring the automated interpretation of normal chest radiographs by AI software to reduce the workload of radiologists.24–28 Regarding the potential use of AI software for imaging ordering and patient scheduling, the algorithms are still in their infancy, but the outlook is promising.29 Most of the respondents agreed on the need for radiologists to dig deeper into AI enabling radiologists to understand not only its basic applications but also its use in specific fields of radiology, including algorithms that can be used in daily practice. These findings highlight the radiologists' continued interest in cutting-edge technology and desire to stay up to date. In light of recent literature, specific training in AI should be included in curricula for radiology residents or even undergraduate programs in medical schools worldwide. This emphasises the urgent requirement for more extensive education regarding the potential uses of AI.10,30,31 At present, only a few surveys inquire about radiologists' needs and fears for the future. The existing literature predominantly focuses on their perspectives regarding the influence of AI on their profession and whether they hold a sceptical or optimistic outlook. Our survey revealed a generally positive sentiment towards the integration of new technologies in radiology. The majority of participants expressed support for incorporating AI into radiological practice, aligning with findings from similar questionnaires.31–34 Among the 116 responses collected concerning future worries in radiology, only four mentioned concerns about being replaced by AI. It is noteworthy that this result significantly differs from the findings of the study by Eiroa et al. which indicated that 25.1% of radiologists expressed concerns about job loss due to AI.10 On the other hand, the primary concern according to our responders was the heavy workload and its dramatic rise foreseen for the years to come. Indeed, this issue has already been addressed in multiple studies worldwide6,35,36 and thoroughly described in the United Kingdom workforce census report by the Royal College of Radiologists for the year 2020.37

Currently, more than 500 AI-based medical devices have been approved by the FDA and they are expected to be a real game-changer for reducing clinical workload. Every single step in the radiology workflow can be enhanced by AI.38 For instance, computer algorithms can be employed to help select the appropriate imaging method, improve image acquisition and raw image processing, boost image post-processing (such as image segmentation, multidimensional image reconstructions, etc.) and even provide support in report writing.39

Nevertheless, the adoption of AI software in clinical practice is still facing important hurdles worldwide. Various reasons why radiology practices are less likely to adopt AI have been reported. These include ethical and legal consequences due to the absence of a clear regulatory framework both at a national and international level, a lack of AI-specific knowledge and training, limitations in digital infrastructure and a general distrust by stakeholders and healthcare authorities.11 Additionally, as highlighted in our survey, concerns such as the privacy of health data can limit its broad use in clinical practice. According to the survey of the ESR, only a small percentage of radiologists employing AI report a significant reduction in the amount of workload.40 Lastly, scepticism about the diagnostic capabilities of AI has also been documented as an important barrier to the widespread use of AI in radiology.41

Our study has some limitations. One of these is closely One of these is closely to the open distribution method employed for the survey. This approach makes it challenging to pinpoint the precise target population that received the questionnaire. As a result, the collected responses might not fully represent the overall opinions of Spanish radiologists.

Additionally, among the respondents of the questionnaire, participants may have mainly consisted of radiologists with a special interest in the topic and with more optimistic views compared to non-responders, introducing a potential selection bias in our study.

ConclusionAI is a fast-growing technology with a transformative and disruptive potential in many sectors of our society, including healthcare and radiology. We found a generally positive attitude among Spanish radiologists toward AI technology. Many radiologists participating in our survey did not seem to be worried about the legal consequences of using AI software, although they expressed concerns about the privacy of patients' health data.

Many of the respondents were unable to answer correctly to specific questions regarding AI and we consider that a solid understanding of the fundamentals of AI is crucial to evaluate properly the potential risks and benefits of implementing this modern technology into the daily clinical routine. We advise that a specialised radiology training program for young doctors and trainees should be promptly designed and implemented, with the ultimate purpose of providing the new generations of specialists with the essential skills and knowledge to be competitive in the ever-changing landscape of radiology, with no fear of being left behind.

- 1

Age groups differed in artificial intelligence (AI) knowledge; radiologists younger than 55 years had better proficiency.

- 2

Most of the respondents viewed the introduction of AI algorithms as an opportunity for radiologists.

- 3

Acquiring a profound understanding of AI fundamentals can aid radiologists in evaluating the risks and benefits associated with AI.

- 1.

Responsible for study integrity: AC and PP.

- 2.

Study conception: AC.

- 3.

Study design: AC.

- 4.

Data acquisition: AC and GM.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: PP and GM.

- 6.

Statistical processing: PP.

- 7.

Literature search: AC, GM, SA and PP.

- 8.

Drafting of the manuscript: AC, GM, SA and PP.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: AC, GM, SA and PP.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: AC, GM, SA and PP.

None.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest declare that it is relevant to the content of this article.

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank all the radiologists and trainees who shared or responded to the survey, and also to Dr. Angela Patricia Salazar Gomez, who assisted in its redaction.