Malignant spinal cord compression is a serious complication secondary to both primary and metastatic vertebral tumours, potentially leading to permanent loss of spinal functions. The Spanish Society of Neuroradiology (SENR), Spanish Society of Emergency Radiology (SERAU), and Spanish Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology (SERME) have convened to draft this consensus document, which describes practical aspects of the radiological management of malignant spinal cord compression. The document includes guidelines on appropriate indications for imaging studies, imaging modality options, technical specifications tailored to different clinical scenarios, recommended time intervals, and the type of facility where the imaging studies can be performed. Additionally, it provides recommendations on using spinal cord compression and instability scales, as well as structured reports for describing the radiological findings.

La compresión medular oncológica es una complicación grave secundaria a procesos oncológicos tanto primarios como metastásicos vertebrales y puede conllevar una pérdida permanente de funciones medulares. La Sociedad Española de Neurorradiología (SENR), Sociedad Española de Radiología de Urgencias (SERAU) y la Sociedad Española de Radiología Musculoesquelética (SERME) se han reunido para redactar este documento de consenso en el que se detallan aspectos prácticos del manejo radiológico de la compresión medular oncológica. Se incluyen consideraciones sobre la indicación de la prueba de imagen, la selección de modalidad de imagen con especificaciones técnicas en función del escenario clínico, los intervalos de tiempo recomendados y el tipo de centro para la realización del estudio de imagen. Además se realizan recomendaciones sobrela utilización de escalas de compresión medular e inestabilidad y sobre el uso de un informe estructurado en la descripción de los hallazgos radiológicos.

Malignant spinal cord compression is a serious complication of metastatic disease and primary vertebral tumours that can result in irreversible loss of spinal cord function. Bone metastases are the most common cause, accounting for 5–20% of malignant spinal cord compression cases, while multiple myeloma is the most frequent primary vertebral tumour associated with this complication. Metastatic spinal cord compression occurs in approximately 2.5–5% of cancer patients, most commonly those with lung, breast or prostate cancer. Metastatic spinal cord compression is the initial clinical presentation of cancer in around 20% of cancer patients, underscoring the need for prompt diagnosis, urgent intervention and disease-specific management.1–4

Most cases of malignant spinal cord compression result from an epidural soft-tissue mass—either metastatic spread or a primary tumour—that exerts direct pressure on the spinal cord. Less commonly, spinal cord compression arises from impaction of bone fragments due to pathological fracture or from deformity or instability caused by a vertebral tumour.1,2,4–8

Early diagnosis of spinal cord compression is essential as initiating treatment before the onset of neurological symptoms significantly improves prognosis. However, over 50% of patients have already lost the ability to walk at the time of diagnosis, greatly limiting the potential for functional recovery. Imaging not only confirms the diagnosis of malignant spinal cord compression, but also quantifies its extent, assesses spinal stability and detects lesions at other vertebral levels.1

This SENR, SERAU, SERME and SERAM consensus document aims to:

- a)

harmonise the criteria for radiological imaging in suspected malignant spinal cord compression;

- b)

provide detailed recommendations on the most appropriate imaging technique based on the clinical context and patient history; and

- c)

propose the use of structured reporting that incorporates specific spinal cord compression and instability scoring systems, in order to reduce inconsistency in the description of radiological findings.

Additional recommendations address the radiological management of patients whose first clinical presentation of cancer is spinal cord compression.

The levels of evidence and grades of recommendation provided are based on the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) classification system.9

Indications for radiological imagingAccording to the 2023 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline ‘Spinal Metastases and Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression’,10 urgent imaging (within 24 h) should be performed in patients with a current or previous history of cancer or in those with suspected malignancy who present with the following symptoms:8,10,11

- 1)

pain consistent with vertebral metastases (Table 1); and

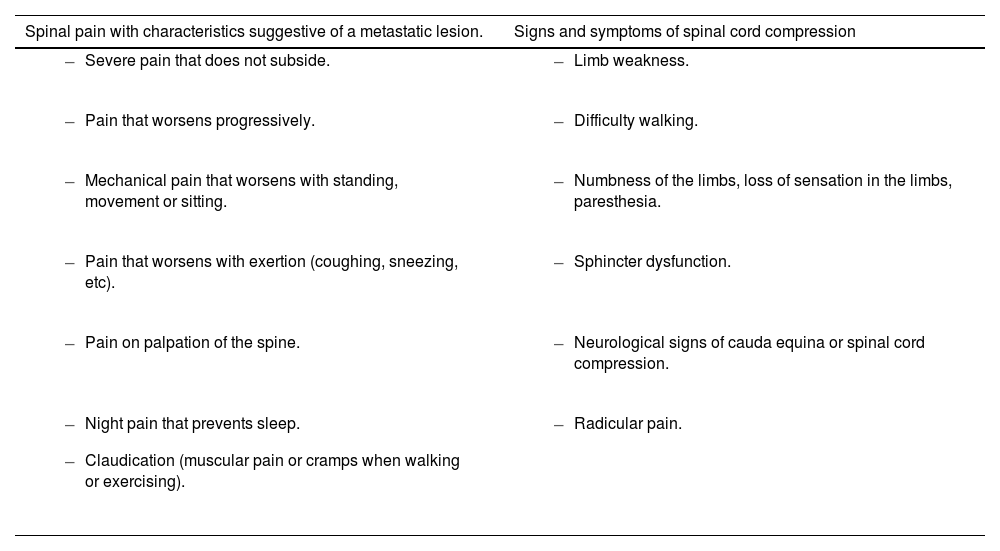

Table 1.Signs and symptoms suggestive of spinal cord compression in patients with history of cancer (Spinal metastases and metastatic spinal cord compression NICE guideline [NG234]; 2023).10

Spinal pain with characteristics suggestive of a metastatic lesion. Signs and symptoms of spinal cord compression - –

Severe pain that does not subside.

- –

Limb weakness.

- –

Pain that worsens progressively.

- –

Difficulty walking.

- –

Mechanical pain that worsens with standing, movement or sitting.

- –

Numbness of the limbs, loss of sensation in the limbs, paresthesia.

- –

Pain that worsens with exertion (coughing, sneezing, etc).

- –

Sphincter dysfunction.

- –

Pain on palpation of the spine.

- –

Neurological signs of cauda equina or spinal cord compression.

- –

Night pain that prevents sleep.

- –

Claudication (muscular pain or cramps when walking or exercising).

- –

Radicular pain.

- –

- 2)

neurological signs or symptoms suggestive of spinal cord compression. Level of evidence 3a, Grade B recommendation.

Spinal pain alone is not an indication for urgent imaging. A thorough clinical examination should be performed to identify warning signs and stratify the risk of spinal cord compression. Key symptoms raising suspicion include sphincter dysfunction, lower limb weakness and saddle anaesthesia.11,12Level of evidence 3a, Grade B recommendation.

Appendix A summarises the signs and symptoms suggestive of malignant spinal cord compression.

Imaging should be requested by the clinician who has assessed the patient and suspects spinal cord compression. This may be an A&E doctor, GP, internist, oncologist or spinal surgeon. The imaging request should include the following information:11,13,14

- 1)

primary tumour, current stage of disease (if known) and time since diagnosis;

- 2)

presence and location of any bone involvement;

- 3)

suspected site of spinal cord compression;

- 4)

details of prior and ongoing treatment, if applicable;

- 5)

symptoms present during the current episode, including details of the type of pain (mechanical/at rest/worsened by standing or Valsalva manoeuvre/pain on palpation—specifying the level), as well as findings from the neurological examination;

- 6)

duration of symptoms and any changes over time;

- 7)

pain response following administration of analgesics;

- 8)

other clinically relevant signs and symptoms, such as dyspnoea, altered level of consciousness, etc;

- 9)

surgical history and any potential contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (e.g. non-compatible pacemakers, cochlear implants etc. See Appendix B). Level of evidence 3a, Grade B recommendation.

The requesting physician should consider administering appropriate analgesia prior to imaging in order to reduce potential motion artifacts. This analgesia should be provided by the medical team responsible for the patient’s care, after reviewing their current medication, possible contraindications and pain severity. Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

Imaging techniquesImaging should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of malignant spinal cord compression, establish the level and degree of compression, detect lesions at other vertebral levels, and assess for possible instability where clinically suspected.15

Magnetic resonance imagingMRI is the preferred imaging modality and the gold standard for acute malignant spinal cord compression diagnosis. It should be carried out on 1.5 T or 3 T scanners.4,15–24Level of evidence 1b, Grade A recommendation.

- a)

Several studies since 1980 have confirmed this technique’s effectiveness in detecting acute spinal cord compression and its superiority to alternative imaging techniques. It enables the assessment of neoplastic lesions (sensitivity: 90.1%, specificity: 96.9%), the presence of spinal cord compression (sensitivity: 93%, specificity: 97%), the degree of spinal cord compression (where applicable) and any associated signal changes within the spinal cord. It enhances treatment planning by allowing accurate delineation of the spinal cord prior to radiotherapy and is more effective than computed tomography (CT) in detecting metastatic lesions.

- b)

NICE (2023) recommends the following standard imaging protocol: Whole-spine MRI including sagittal T1-weighted and/or STIR sequences, sagittal T2-weighted sequences, and axial T2-weighted sequences at the level of suspected spinal cord compression. Slice thickness should be 3–5 mm. Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

- •

The entire spine should be assessed, as symptoms do not always correlate with the level of compression. Furthermore, up to 25% of patients present with multiple lesions resulting in spinal cord compression at various spinal levels.25Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

- •

- c)

For patients who are unable to cooperate or require expedited imaging due to clinical factors (such as dementia, impaired consciousness or claustrophobia), a rapid acquisition protocol is advised. This should include sagittal T2-weighted or STIR sequences of the entire spine, along with axial T2-weighted sequences at the level of suspected spinal cord compression. Level of evidence 2b, Grade B recommendation.

- •

This protocol is not inferior to the standard protocol for detecting malignant spinal cord compression. But given the limited number of studies evaluating the utility of this protocol in detecting other clinically relevant lesions (e.g. abscesses, epidural haematomas), the standard imaging protocol remains the preferred option in routine practice.

- •

- d)

An abbreviated protocol may be used as an alternative18 to the standard protocol, with only a sagittal T2-weighted Dixon sequence and axial T2-weighted sequences in the region of identified compression.26Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

- •

Dixon imaging exploits the chemical shift between water and fat protons to decompose their respective signals within a single voxel.

- •

A Dixon sequence generates four types of images: in-phase (IP, equivalent to an anatomical image without fat suppression), out-of-phase (OP), water-only images (equivalent to anatomical images with fat suppression) and fat-only images (equivalent to water suppression).

- •

The T2 Dixon sequence simultaneously offers STIR-type contrast from the water-only images and T1-type contrast from the fat-only images.

- •

T2 Dixon has proven effective in spinal MRI for detecting metastatic and multiple myeloma lesions and can replace traditional T1 and STIR sequences without compromising diagnostic accuracy.

- •

A standard MRI protocol is shown in Appendix C.18

- e)

In cases of prior spinal instrumentation, metal artifact reduction sequences (MARS) should be employed wherever available and 3 T scanners should be avoided in order to reduce artifacts.

- f)

Several sequences are useful for diagnosing and assessing vertebral metastases—such as in-phase and out-of-phase sequences or diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI)—although their use is not essential for the diagnosis of malignant spinal cord compression and they are not routinely recommended for this purpose. The aforementioned standard protocol provides sufficient imaging for both the detection and assessment of spinal cord compression. Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

Appendix D provides further detail on the MRI sequences recommended in this section, as well as on additional sequences useful for detecting vertebral metastases that are not included in the standard spinal cord compression protocol. The sequences recommended in this section are solely intended for the assessment of malignant spinal cord compression. 6,15,18,27,28

Computed tomographyCT is considered the second-line diagnostic modality for the evaluation of malignant spinal cord compression and is also indicated as a complementary study in specific clinical scenarios. Reconstructions should always be obtained using both bone and soft tissue windows, with bone and soft tissue filters applied respectively, and a maximum slice thickness of 2 mm to ensure high-quality multiplanar reconstructions. CT of the spine is indicated in the following circumstances:10,15,29–32

- a)

MRI contraindication (see Appendix B). In patients with a contraindication to MRI, a contrast-enhanced whole-spine CT should be performed upon request by the referring physician. Before administering iodinated contrast, it is necessary to confirm the absence of contraindications including allergy or risk of contrast-induced nephropathy. If any are present, a non-contrast CT scan should be performed. The use of MAR algorithms should be considered in the presence of spinal instrumentation. Level of evidence 2b, Grade B recommendation.

- •

Contrast-enhanced CT of the spine closely correlates with MRI in evaluating the degree of spinal cord compression, and thus serves as a valuable alternative when MRI is not feasible.

- •

However, it is not suitable for evaluating the spinal cord and is less sensitive than MRI for detecting metastases.

- •

- b)

Assessment of spinal instability. CT is the preferred imaging technique for spinal instability assessment. Contrast administration is not required, and CT should be considered complementary rather than a substitute for MRI. Imaging from a recent contrast-enhanced CT, performed for tumour staging or follow-up, may also be used to assess spinal instability. CT should be performed if there are MRI findings or clinical suspicion suggestive of instability. Imaging should be limited to the region of the spine where instability is suspected. The indication for CT should be made by the medical team treating the patient, based on clinical examination and the patient’s presenting symptoms. Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

- •

Clinical suspicion of instability: presence of mechanical spinal pain, new-onset or painful spinal deformity or neurological symptoms that appear when the patient bears their own weight.

- •

MRI findings suggestive of instability: misalignment of the vertebral column at the level of the neoplastic lesion, vertebral body collapse or involvement of the posterolateral elements of the vertebra.

- •

MRI alone is not sufficient for the assessment of spinal instability. CT allows differentiation between blastic, lytic or mixed lesions and facilitates the description of vertebral collapse which is essential when assessing spinal instability.

- •

- c)

Imaging for surgical, radiotherapy or vertebroplasty planning. In these circumstances, contrast administration is not required and CT should be considered complementary rather than a substitute for MRI. The indication for CT should be made by the medical team treating the patient, based on clinical examination and the planned therapeutic approach. Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

- d)

In cases where MRI is unavailable within 24 h and patient transfer is either not feasible or would exceed this timeframe, such as in clinically unstable patients or in remote locations that hinder timely transfer. Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

- •

MRI is the reference standard for the assessment of malignant spinal cord compression and should always be the first-line diagnostic modality. However, in situations where MRI cannot be performed within 24 h, contrast-enhanced CT is recommended in order to obtain diagnostic information and support treatment decision-making.

- •

Appendix C provides an example of a contrast-enhanced CT protocol for the evaluation of the spine.33

CT myelographyCT myelography is a diagnostic option reserved for selected cases in which MRI cannot be performed due to contraindications and additional information is required beyond that provided by standard spinal CT—particularly for assessing the configuration of the thecal sac, the presence of stenosis and the degree of spinal cord compression when these findings are not sufficiently clear. CT myelography is also indicated when MRI is severely affected by artifacts, hindering proper assessment of the spinal canal. This procedure should be performed exclusively in neurosurgical centres by experienced staff and only following indication by the medical team treating the patient. It is important to note that this technique may lead to complications and usually involves patient transfer, causing potential delays.10,34

The most common complications include bleeding and infection at the puncture site, inadvertent injection of contrast into the spinal cord or conus medullaris and allergic reactions to iodinated contrast. Seizures have also been reported but are extremely rare.35Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

Bone scintigraphy and plain radiographyBone scintigraphy and plain radiography are not currently indicated in the assessment of malignant spinal cord compression.10Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

- a)

Plain radiography can be used to assess spinal instability when obtained during the episode in which malignant spinal cord compression is suspected. Nevertheless, CT is the preferred modality for evaluating instability.

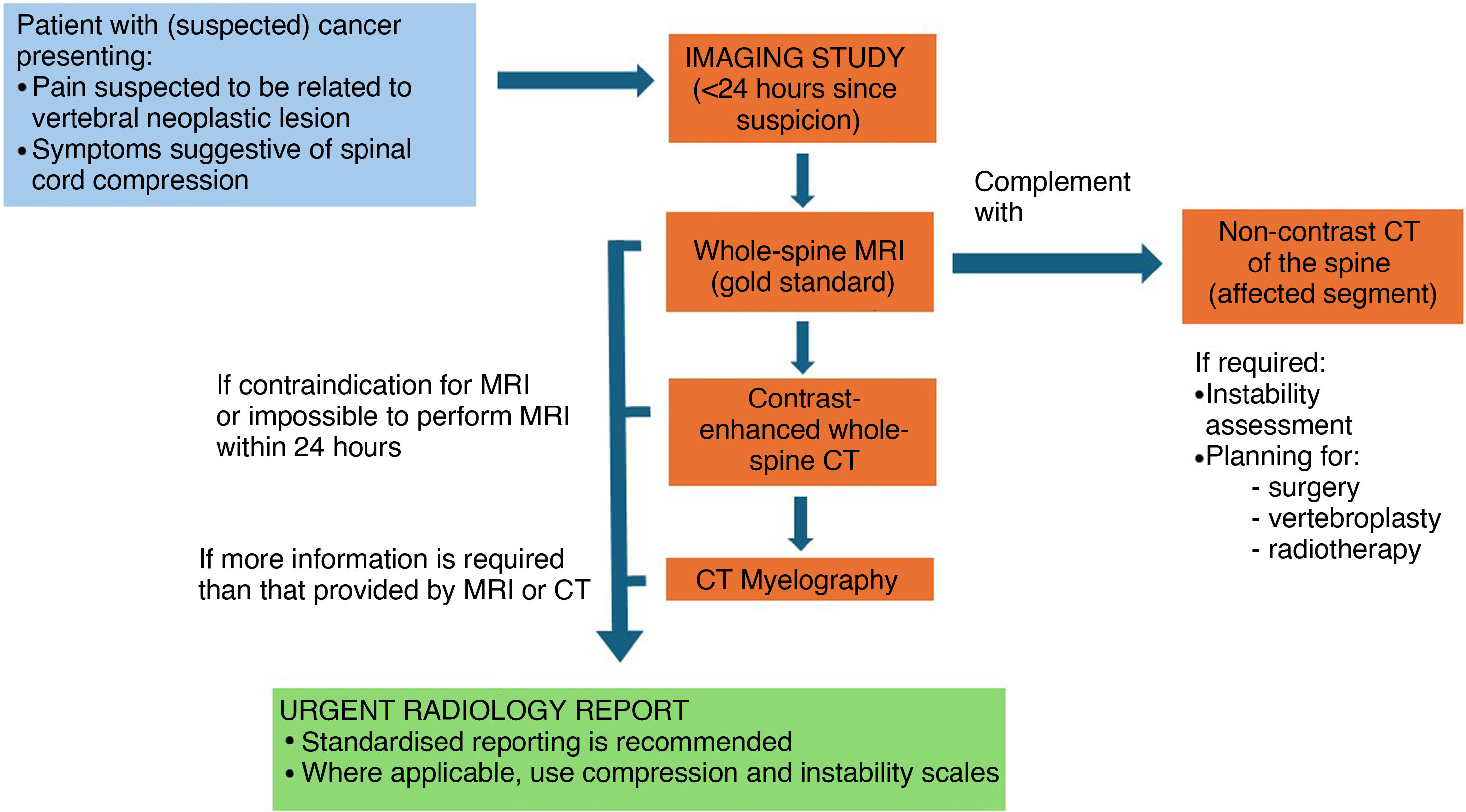

Fig. 1 outlines the recommended radiological imaging approach based on the patient’s clinical situation.

Practical considerations in radiological imagingIf malignant spinal cord compression is suspected, imaging must be performed as soon as possible and within 24 h of the onset of clinical suspicion.8,10,15Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

MRI is the imaging modality of choice for the evaluation of spinal cord compression.4,10,15,21,23Level of evidence 1b, Grade A recommendation.

MRI may be performed at the hospital where the patient is located and does not need to be carried out in a specialist oncology or spinal surgery centre.10Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

If MRI cannot be performed within 24 h at the hospital where the patient is located, transfer should be arranged to a facility where the examination can be carried out. This decision should be made by the clinician requesting the imaging study.10Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

In cases where MRI is not available within 24 h and the patient cannot be transferred within that timeframe—due to clinical instability or a geographical location preventing transfer within 24 h—a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the entire spine should be performed.15,29Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

If a CT scan is required to assess potential spinal instability or to plan treatment, it should also be performed within 24 h of the onset of clinical suspicion. Similarly, if CT myelography is indicated, it must be carried out within the same 24-h timeframe to avoid delays in initiating treatment.10Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

In cases of suspected vertebral metastasis with no spinal cord compression, an MRI should be performed within seven days at the hospital where the patient is being managed. This procedure does not need to be performed in a specialist oncology or spinal surgery centre.10Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

All examinations must follow a defined imaging protocol and be interpreted by a radiologist. The radiologist must supervise the examination to ensure that its diagnostic quality is adequate.10Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

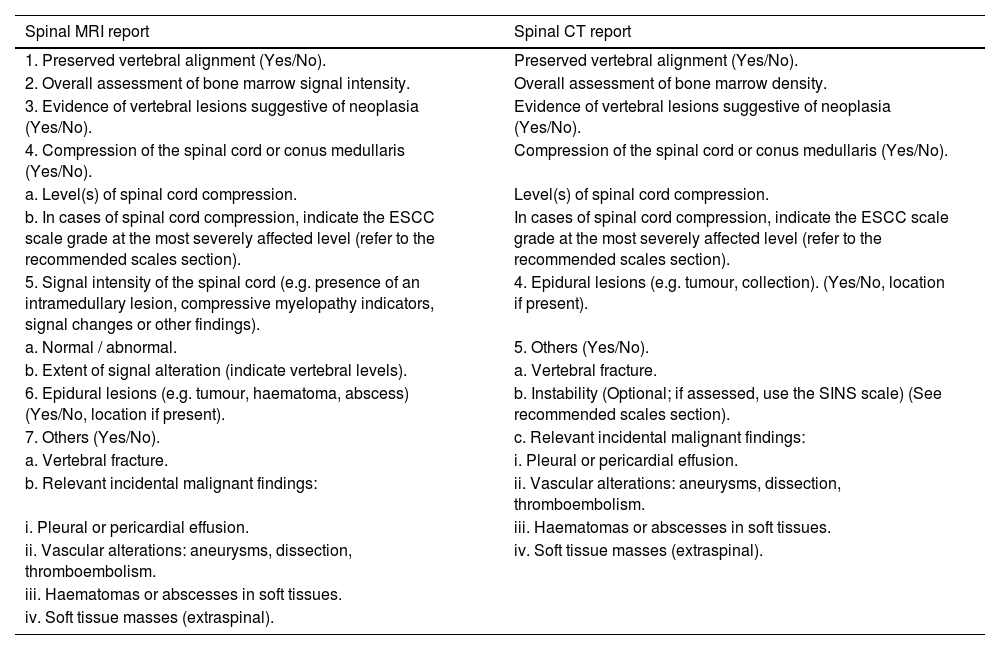

Radiology reportingThe radiological report should be issued as a matter of urgency by the on-call radiologist or by the appropriate specialist section, according to the centre’s organisational structure. In certain circumstances, the report may be written by a radiology trainee, provided they are under appropriate supervision.10,36,37Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

Structured reportStructured reporting with clear, precise content is advised.38Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

The report should provide detailed information on vertebral alignment, vertebral tumour lesions, epidural lesions and fractures. It should also indicate the presence of spinal cord compression, any abnormal signal within the spinal cord and signs suggestive of instability. Clinically relevant incidental findings must also be reported.38,39Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

If spinal cord compression is present, the report should include grading according to the Epidural Spinal Cord Compression (ESCC) scale. Additionally, the Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score (SINS) may be included when the imaging study has been requested to evaluate suspected spinal instability.1,2,10,40Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

The following structured reports are proposed for MRI and CT reporting in the assessment of malignant spinal cord compression:

| Spinal MRI report | Spinal CT report |

|---|---|

| 1. Preserved vertebral alignment (Yes/No). | Preserved vertebral alignment (Yes/No). |

| 2. Overall assessment of bone marrow signal intensity. | Overall assessment of bone marrow density. |

| 3. Evidence of vertebral lesions suggestive of neoplasia (Yes/No). | Evidence of vertebral lesions suggestive of neoplasia (Yes/No). |

| 4. Compression of the spinal cord or conus medullaris (Yes/No). | Compression of the spinal cord or conus medullaris (Yes/No). |

| a. Level(s) of spinal cord compression. | Level(s) of spinal cord compression. |

| b. In cases of spinal cord compression, indicate the ESCC scale grade at the most severely affected level (refer to the recommended scales section). | In cases of spinal cord compression, indicate the ESCC scale grade at the most severely affected level (refer to the recommended scales section). |

| 5. Signal intensity of the spinal cord (e.g. presence of an intramedullary lesion, compressive myelopathy indicators, signal changes or other findings). | 4. Epidural lesions (e.g. tumour, collection). (Yes/No, location if present). |

| a. Normal / abnormal. | 5. Others (Yes/No). |

| b. Extent of signal alteration (indicate vertebral levels). | a. Vertebral fracture. |

| 6. Epidural lesions (e.g. tumour, haematoma, abscess) (Yes/No, location if present). | b. Instability (Optional; if assessed, use the SINS scale) (See recommended scales section). |

| 7. Others (Yes/No). | c. Relevant incidental malignant findings: |

| a. Vertebral fracture. | i. Pleural or pericardial effusion. |

| b. Relevant incidental malignant findings: | ii. Vascular alterations: aneurysms, dissection, thromboembolism. |

| i. Pleural or pericardial effusion. | iii. Haematomas or abscesses in soft tissues. |

| ii. Vascular alterations: aneurysms, dissection, thromboembolism. | iv. Soft tissue masses (extraspinal). |

| iii. Haematomas or abscesses in soft tissues. | |

| iv. Soft tissue masses (extraspinal). |

The scales included in this consensus document were created and are recommended by the Spine Oncology Study Group (SOSG).

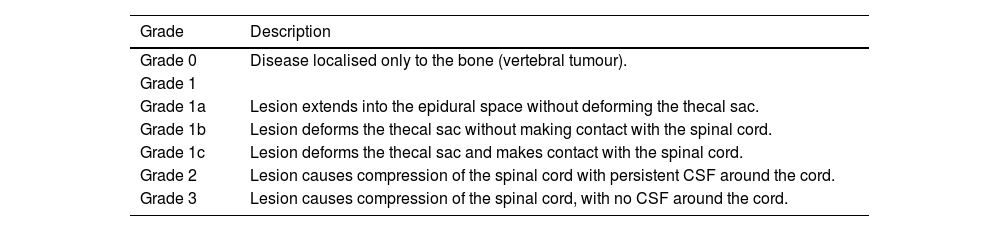

Malignant spinal cord compression should be assessed using the ESCC scale, also known as the Bilsky scale.1,2,29,41–43Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

- a)

It is a six-grade visual scale based on qualitative assessment.

- b)

The scale standardises how spinal cord compression is described among professionals, supports early identification of rapidly progressive paraparesis at levels C7–L1 (when grade 2 or 3 anterolateral or circumferential compression is present) and helps predict ambulatory function after radiotherapy.

- c)

MRI is the primary modality for assessment, although CT can also be used.

- d)

Assessment should focus on the level with the greatest degree of spinal cord compression.

- e)

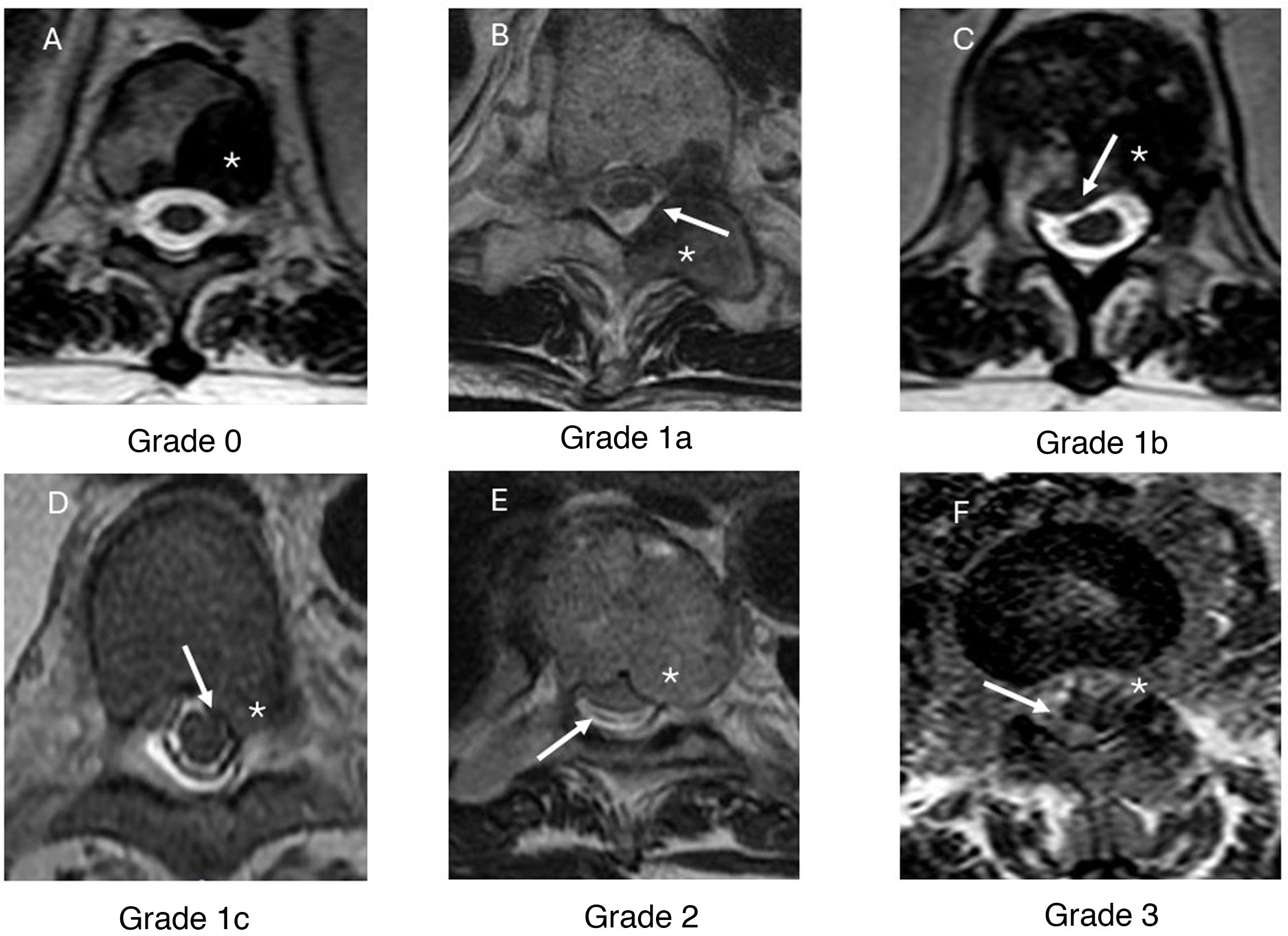

Axial T2-weighted sequences are used to evaluate the tumour lesion, spinal cord and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) when visible. The degree of compression is graded according to the radiological criteria summarised in Table 2. (Fig. 2)

Table 2.ESCC scale (Bilsky scale).41

Grade Description Grade 0 Disease localised only to the bone (vertebral tumour). Grade 1 Grade 1a Lesion extends into the epidural space without deforming the thecal sac. Grade 1b Lesion deforms the thecal sac without making contact with the spinal cord. Grade 1c Lesion deforms the thecal sac and makes contact with the spinal cord. Grade 2 Lesion causes compression of the spinal cord with persistent CSF around the cord. Grade 3 Lesion causes compression of the spinal cord, with no CSF around the cord. CSF: cerebrospinal fluid.

Figure 2.Epidural Spinal Cord Compression (ESCC) scale, axial T2-weighted images. Grades of spinal cord compression according to the tumour’s location within the vertebra, its extension into the spinal canal and the degree of spinal cord involvement. In grade 0 (A), the metastatic lesion is confined to the vertebra (*) with no epidural component or spinal cord compression. In grade 1a (B), the lesion extends from the vertebral body into the epidural space. In this example, a metastasis is seen in the left posterior elements (*) with extension into the epidural space (white arrow). In grade 1b (C), a metastatic lesion is present in the vertebral body (*) with epidural extension causing deformation of the thecal sac (white arrow) but it does not come into contact with the spinal cord. Image D presents an example of a grade 1c lesion, showing a metastatic lesion in the vertebral body (*) that deforms the thecal sac and comes into contact with the spinal cord, without causing compression (white arrow). In grade 2 (E), the metastatic lesion (*) compresses the spinal cord, although cerebrospinal fluid remains visible around it (white arrow). In grade 3 (F), the spinal cord is compressed by a metastatic lesion (*) with no cerebrospinal fluid visible around the cord (white arrow).

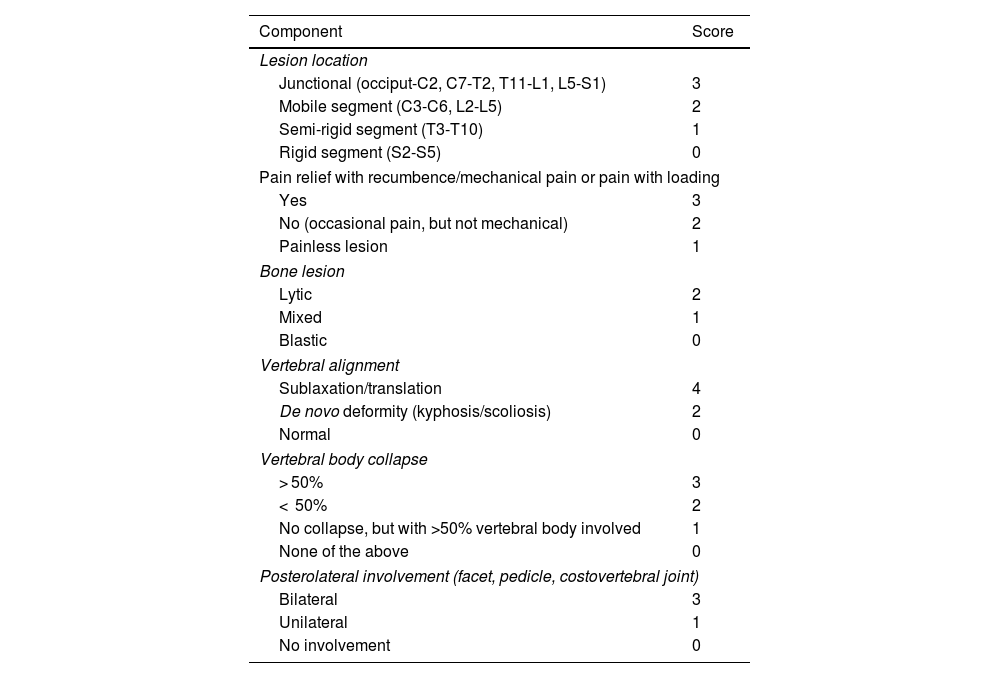

Spinal instability is assessed using the SINS scale. Its use is recommended by the 2023 NICE guidelines.10,31,40,44–48Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

- a)

It is a quantitative scale that assesses radiological and clinical (pain) items by assigning a score to each component based on the findings. Higher scores indicate greater instability. A final score is obtained by adding together the individual component scores.

- b)

This scale can be reliably reproduced by different specialists. It also has prognostic value as it indicates greater survival in patients with indeterminate instability who undergo surgery, compared to those with established instability treated surgically.40

- c)

The scale requires CT or plain radiographic images (anteroposterior and lateral views of the spine), along with basic clinical details regarding the patient’s pain. As previously mentioned, CT is the imaging modality of choice for assessing instability. Plain radiography should only be used if it has already been performed and is available; it should not be requested as the first-line investigation for spinal instability.

- d)

If multiple lesions are present, a separate SINS score should be calculated for each lesion, with an emphasis on the highest score.

- e)

It is essential to use multiplanar reconstructions (sagittal and coronal) in the CT study as they allow for proper assessment of each item in the scale. Subluxation and translation are assessed on sagittal reconstructions; spinal deformities are more readily identified on coronal and sagittal views; involvement of the posterior elements may require multiplanar image analysis; and detection of vertebral body collapse should be carried out using both coronal and sagittal reconstructions.

- f)

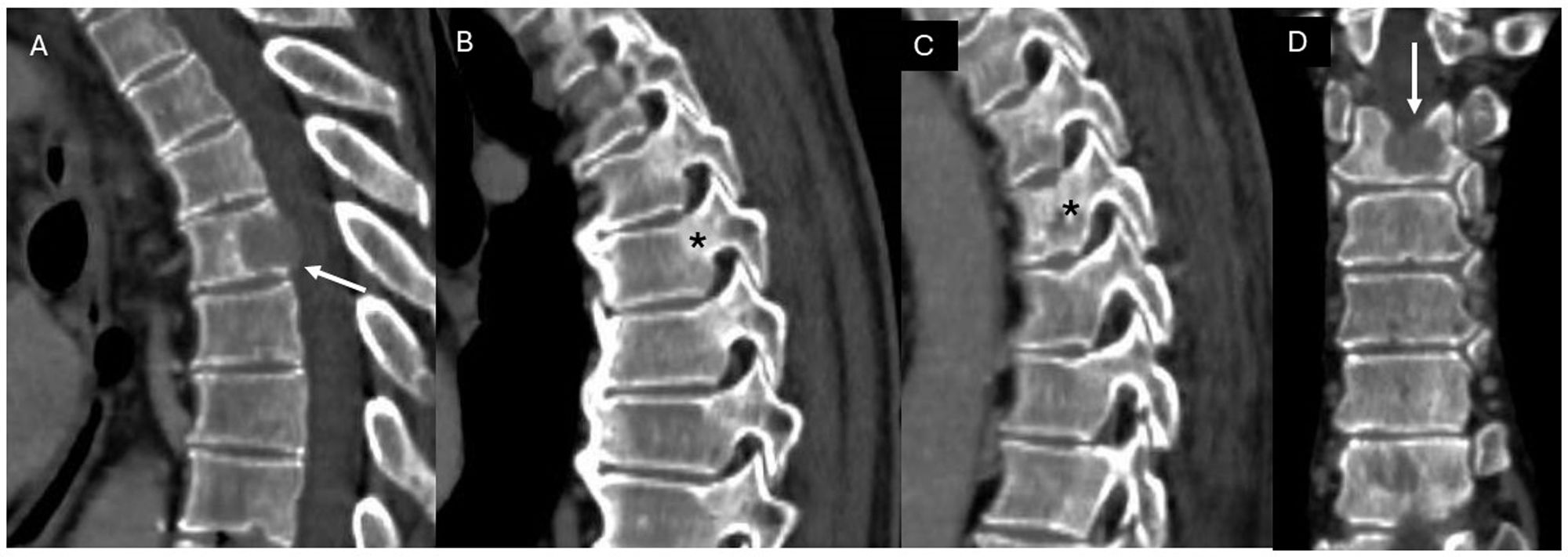

Table 3 lists the components assessed with the SINS scale based on radiological and clinical criteria, together with the score assigned to each finding (Fig. 3).

Table 3.Instability scale (SINS score).31

Component Score Lesion location Junctional (occiput-C2, C7-T2, T11-L1, L5-S1) 3 Mobile segment (C3-C6, L2-L5) 2 Semi-rigid segment (T3-T10) 1 Rigid segment (S2-S5) 0 Pain relief with recumbence/mechanical pain or pain with loading Yes 3 No (occasional pain, but not mechanical) 2 Painless lesion 1 Bone lesion Lytic 2 Mixed 1 Blastic 0 Vertebral alignment Sublaxation/translation 4 De novo deformity (kyphosis/scoliosis) 2 Normal 0 Vertebral body collapse > 50% 3 < 50% 2 No collapse, but with >50% vertebral body involved 1 None of the above 0 Posterolateral involvement (facet, pedicle, costovertebral joint) Bilateral 3 Unilateral 1 No involvement 0 Figure 3.Example of instability assessment in a patient with a metastatic lesion in the T5 vertebra who presented with thoracic pain with relief at rest. Contrast-enhanced CT of the thoracic spine, with sagittal (A-C) and coronal (D) reconstructions. A metastatic lesion is identified (white arrow, images A and D) in the body of the T5 vertebra. It affects a semi-rigid segment (thoracic spine, 1 point), with pain relief at rest (3 points), has a lytic appearance (2 points), with normal alignment (0 points), no collapse of the vertebral body (0 points) and no posterolateral involvement (*, images B and C) (0 points): SINS score of 6, stable.

- g)

A score of 6 or below defines a stable spine; scores between 7 and 12 indicate indeterminate stability and scores from 13 to 18 are considered indicative of spinal instability.

- h)

Surgical evaluation is required for a score of 7 or higher.

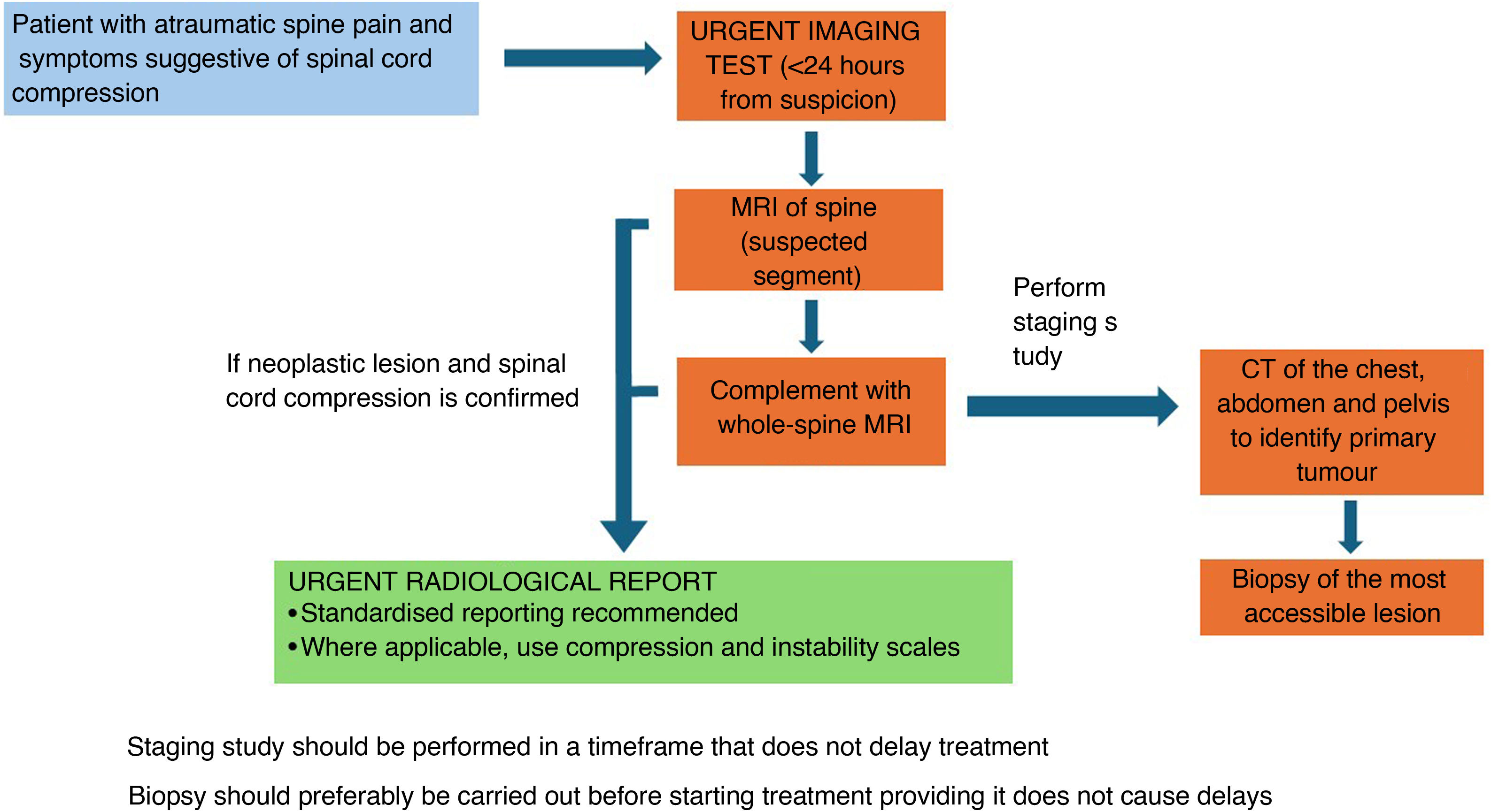

In patients with acute non-traumatic spinal pain and neurological symptoms suggestive of spinal cord compression, an urgent MRI (within 24 h) should be performed at the level suspected to be affected based on the clinical examination, even if there is no known history of cancer.49Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

If a tumoral lesion is identified, the assessment should be completed with a whole-spine MRI.15,25Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

In addition to MRI, these patients should undergo staging with a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (unless contraindicated) to help identify the primary tumour and assess tumour stage. The staging study should be carried out without causing delays to treatment. If prompt intervention is necessary—for example, urgent surgery due to spinal instability—the CT scan for tumour staging may be postponed. Additional complementary studies are sometimes required (e.g. mammography, thyroid ultrasound).50–53Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

Biopsy is necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis, evaluate the tumour’s radiosensitivity and determine the suitability of additional treatment options.50–53Level of evidence 3b, Grade B recommendation.

The biopsy should be taken from the most accessible lesion. If spinal surgery is performed, a tumour tissue sample may be obtained during the same surgical procedure. Ideally, the biopsy should be performed before initiating treatment; however, treatment should not be delayed while awaiting biopsy.50,51Level of evidence 5, Grade D recommendation.

Fig. 4 summarises the radiological management of patients presenting with malignant spinal cord compression from an unknown primary tumour.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAdán Bello Báez, Daniela de Araujo Martins-Romeo, Estanislao Arana Fernández de Moya and Almudena Pérez Lara: concept, drafting and critical review of the article, final approval of the manuscript.

FundingThis research has not received funding support from public sector agencies, the business sector or any non-profit organisations.