Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia worldwide. Previous studies have described that certain clinical characteristics such as age, obesity, the type of AF, and imaging-based factors, such as left atrial (LA) volume, mean density (calculated as the average of Hounsfield Units values in a certain región of interest), and volume of cardiac adipose tissue, may increase the risk of recurrence following pulmonary vein ablation. However, there have been contradictory results regarding radiological variables in previous studies. The objective of this study was to evaluate these clinical and radiological risk factors obtained from computed tomography (CT) studies.

Materials and methodsThis retrospective case-control study included all patients with AF who underwent initial radiofrequency or cryoablation of pulmonary veins after undergoing contrast-enhanced CT between 2017 and 2021. Clinical variables such as age, gender, comorbidities, medications used after ablation, type of AF, and radiological variables obtained from volumetric segmentation of CT studies were collected. Radiological variables included LA volume, mean density, and volume of epicardial, periatrial, and interatrial adipose tissue. The occurrence or absence of AF recurrence within 12 months after ablation was also recorded. These variables were subjected to univariate and multivariate analysis to evaluate the risk of recurrence.

ResultsAmong the total number of included patients, 40 had paroxysmal AF and 12 had persistent AF. During the follow-up period, 12 patients (23.1%) experienced AF recurrence, while 40 patients (76.9%) remained in sinus rhythm. There were statistically significant differences in LA volume based on the type of AF, with higher volumes observed in patients with persistent AF (119.16 +/− 32.38 cc) compared to the rest (90.99 +/− 28.34 cc). Regarding the differences between patients with and without recurrence after ablation, only LA volume (p < 0.05) and periatrial adipose tissue volume (p < 0.01) were significantly higher in patients with recurrence.

ConclusionThe type of atrial fibrillation, increased left atrial volume, and increased periatrial adipose tissue volume are risk factors for recurrence in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing pulmonary vein ablation using cryoablation or radiofrequency.

La fibrilación auricular (FA) es la arritmia cardíaca más frecuente globalmente. Se ha descrito previamente que algunas características clínicas como la edad, obesidad, el tipo de FA y otras, obtenidas mediante estudios de imagen, como el volumen de la aurícula izquierda (AI), la densidad media (calculada a partir del promedio de los valores de Unidades Hounsfield en una región de interés) y volumen del tejido graso cardiaco podrían aumentar el riesgo de recurrencia tras la ablación de venas pulmonares, existiendo resultados contradictorios entre algunos estudios previos con respecto a las variables radiológicas. El objetivo de este estudio fue el de evaluar estos factores de riesgo clínicos y radiológicos obtenidos a partir de estudios de tomografía computarizada.

Materiales y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de casos y controles incluyendo a todos los pacientes con FA sometidos a una primera ablación por radiofrecuencia o crioablación de venas pulmonares posterior a la realización de una tomografía computarizada (TC) con contraste entre 2017 y 2021. Se recopilaron variables clínicas como la edad, sexo, comorbilidades, medicaciones empleadas tras la ablación, tipo de FA y radiológicas obtenidas a partir segmentación volumétrica de los estudios de TC, como volumen de AI, la densidad media y volumen del tejido graso epicárdico, periatrial e interatrial, así como la aparición o no de recurrencia de la FA tras 12 meses desde la ablación. Estas variables fueron sometidas a un análisis univariante y multivariante para evaluar el riesgo de recurrencia.

ResultadosDel total de pacientes incluidos, 40 tenían FA paroxística y 12 persistente. 12 (23,1%) mostraron recurrencia durante el periodo de seguimiento y 40 (76,9%) se mantuvieron con ritmo sinusal. Existieron diferencias estadísticamente significativas para el volumen de la AI según el tipo de FA, siendo mayor en los pacientes con FA persistente (119,16 +/− 32,38 cc), respecto al resto (90,99 +/− 28,34 cc). En cuanto a las diferencias entre los pacientes con y sin recurrencia tras la ablación, únicamente el volumen de la AI (p < 0.05) y el volumen del tejido graso periatrial (p < 0.01) fueron significativamente mayores en los pacientes con recurrencia.

ConclusiónEl tipo de fibrilación auricular, el aumento del volumen de la aurícula izquierda y del tejido graso periatrial son factores de riesgo para la recurrencia en pacientes con fibrilación auricular sometidos a ablación de venas pulmonares mediante crioablación o radiofrecuencia.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common form of cardiac arrhythmia globally, with a variable prevalence that has risen in recent decades. Its incidence increases with age, from an estimated 0.12–0.16% in individuals younger than 49 years to 10–17% in those over 79 years.1 It is estimated that by 2050, around 17.9 million people in Europe will have developed AF.2

The duration of the rhythm disturbance determines whether AF is classified as paroxysmal (lasting less than seven days) or persistent (lasting between seven days and one year). Classifying atrial fibrillation based on its duration is crucial, as this factor significantly influences long-term prognosis and the choice of therapeutic strategies for rhythm restoration.3,4

Treatment focuses on preventing cardioembolic events through anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy at the same time as managing rhythm and/or heart rate with appropriate medications. With paroxysmal AF, episodes can be self-limiting or treated by cardioversion with the aim of restoring sinus rhythm.3 Due to the high recurrence rates following electrical or pharmacological cardioversion and advancements in interventional cardiology, pulmonary vein isolation has become a widely accepted treatment for patients with symptomatic, drug-resistant AF.5 This approach achieves a 12-month success rate of approximately 59.9%–65.4% with either radiofrequency ablation or catheter cryoablation.6

Some factors, such as the AF type, have been associated with lower success rates following ablation. In one study by Deng et al.,7 the success rate in patients with paroxysmal AF was 70%, compared to 50% in patients with persistent AF.

These differences are thought to result from morphological changes in the left atrium (LA), such as atrial dilatation and wall thickness following prolonged periods of rhythm disturbance. Other factors that have been associated with an increased risk of recurrence following catheter ablation include obesity, metabolic syndrome and older age.8–10

In their study, Mahajan et al.11 demonstrated that sustained obesity contributes to atrial remodelling, characterised by increased LA volume, conduction abnormalities, atrial fibrosis, and an elevated risk of developing AF.

Elsewhere, it has been reported that an increase in the quantity and mean density of adipose tissue—whether epicardial (EAT), periatrial (PAT), or interatrial (IAT)—may be associated with a higher risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) and its recurrence after ablation.12–15 This has been assessed using tissue segmentation techniques in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and echocardiography studies, which quantify the thickness, volume, and density of these tissues, though results across studies are sometimes contradictory.16–25

Therefore, our study aimed to assess the association between clinical, volumetric, and densitometric variables of the LA, as well as the EAT, PAT, and IAT—measured through CT imaging—and the recurrence of AF in patients undergoing pulmonary vein isolation.

MethodsThis is a retrospective case-control study that includes all consecutive AF patients who underwent their first pulmonary vein radiofrequency ablation or cryoablation after a contrast-enhanced CT between 2017 and 2021. We excluded patients whose CT studies contained motion artifacts or in which LA was insufficiently enhanced. Cases were made up of those patients who experienced recurrence during the follow-up period while controls were those patients who maintained a sinus rhythm.

We gathered demographic and relevant clinical data including age, sex, body mass index (BMI) and comorbidities (type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and systemic arterial hypertension) from electronic medical records. We divided the sample according to the AF type (paroxysmal or persistent) to compare the characteristics of both groups. We also recorded whether there was a sinus rhythm or AF recurrence during each patient’s follow-up visits at 3, 6 and 12 months. All data were treated confidentially and all patients signed an informed consent form prior to the procedure. The ethics committee of our centre waived the need for informed consent for participation in the study due to the retrospective nature of the study which reviewed past medical records. The protocol was registered under no. PI2023-045.

CT scans and cardiac adipose tissue analysisThe CT studies were performed using a 64-slice CT scanner (Philips Brilliance CT). The acquisition protocol employed to acquire the images used retrospective electrocardiographic gating, dose modulation, a voltage of 120 kV, a collimation of 64 × 0.625 mm, and a rotation time of 0.35 seconds. A standard dose of 80 ml of iodinated contrast with a concentration of 400 mgI/mL was injected at a rate of 4 ml/s, followed by 30 ml of saline at the same rate.

The study was conducted using the bolus tracking technique, with the region of interest placed in the LA and a trigger threshold set at 130 Hounsfield units (HU). Image acquisition commenced 10 seconds after the threshold was reached. CT data sets were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 1 mm.

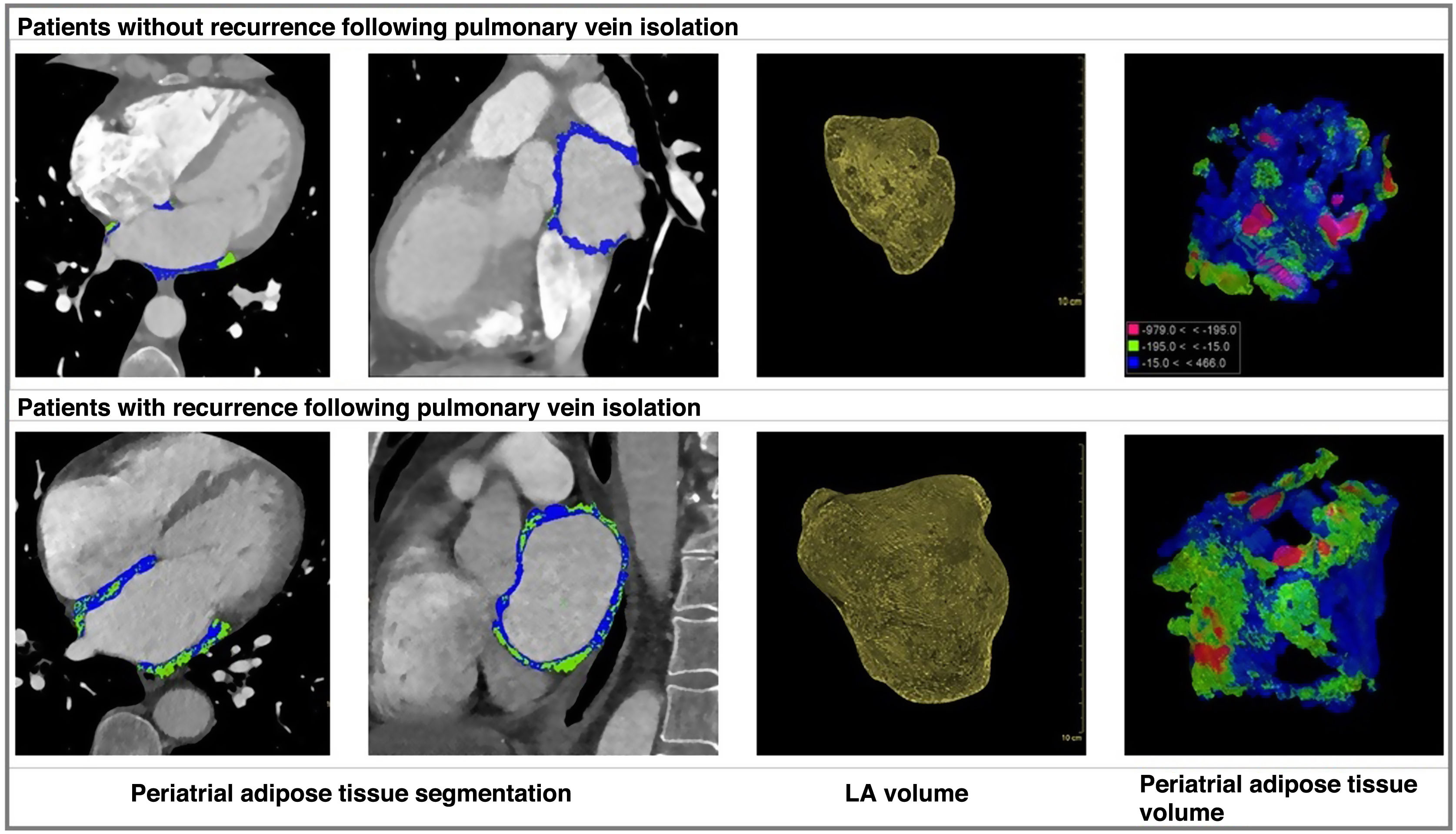

Measurements of the LA volume as well as the volume and density of the EAT, PAT and IAT were taken during the cardiac cycle corresponding to 75% of the R-R interval, using semi-automatic segmentation by manually marking the corresponding tissue in the Philips IntelliSpace software, version 12.1. All cases were evaluated and segmented by a radiologist from our hospital’s cardiac imaging department. The EAT volume was manually traced from the upper edge of the aortic arch to the diaphragm, while PAT volume was calculated from the mitral annulus to the roof of the LA, and IAT volume was taken from within the interatrial septum. Sub-segmentation of adipose tissue was based on an attenuation range of between −195 and −15 HU.

Statistical analysisWe determined the normality of all quantitative variables included in this study using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Variables with parametric distribution were described by their mean and standard deviation, while non-parametric variables were described by their median and quartiles. Qualitative variables were described by their absolute and relative frequency.

A first univariate analysis was performed comparing the presence of AF recurrence with the following risk factors: age, sex, BMI, AF type (paroxysmal or persistent), LA volume, as well as volume and density of PAT, IAT and EAT. For this purpose, we used the χ2 statistical test for qualitative variables, the Student’s t-test for parametric quantitative variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric quantitative variables. All variables with a p-value of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Based on these results, statistically significant variables were subjected to a multivariate analysis, using the logistic regression and proportional hazards models.

A second univariate analysis was performed to compare LA volume, as well as the mean density and volume of the PAT, IAT and EAT between patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF, using the Student’s t-test for parametric quantitative variables and the Mann–Whitney U-test for non-parametric quantitative variables, considering these to be statistically significant when the p-value < 0.05. The statistical analysis was carried out with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22.0.

ResultsWe gathered data on a total of 75 AF patients treated with pulmonary vein isolation. Of these, only 52 had CT scan images with adequate diagnostic quality, no motion artifacts and follow-up records for the following 12 months. These 52 patients included 21 women and 31 men, with a median age of 60 (IQR: 54.5–66) and 58 (IQR: 53–63) years, respectively. Of the 23 patients excluded, 10 had persistent AF and 13 had paroxysmal AF. The reasons for exclusion were a lack of follow-up records after ablation or motion artifacts on CT images.

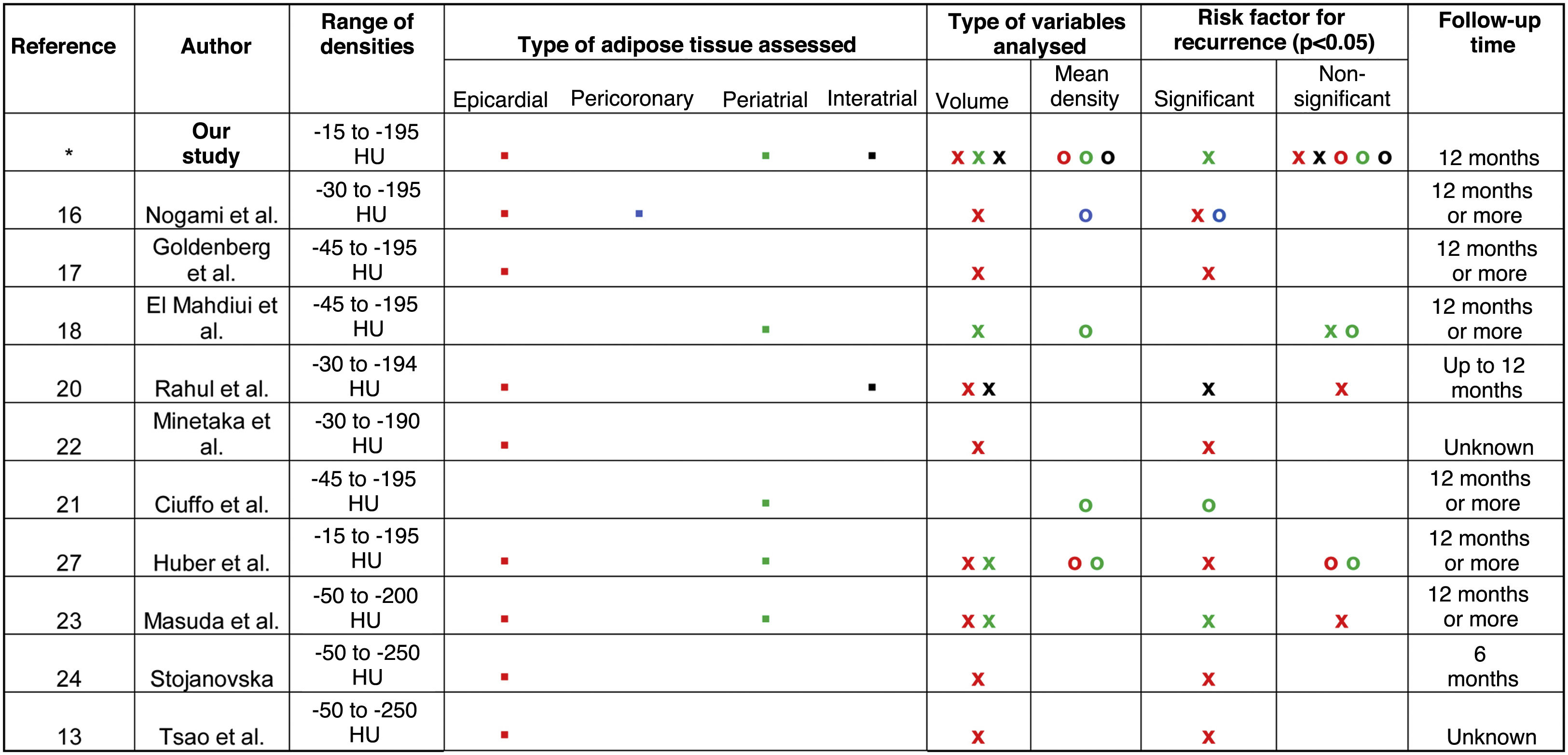

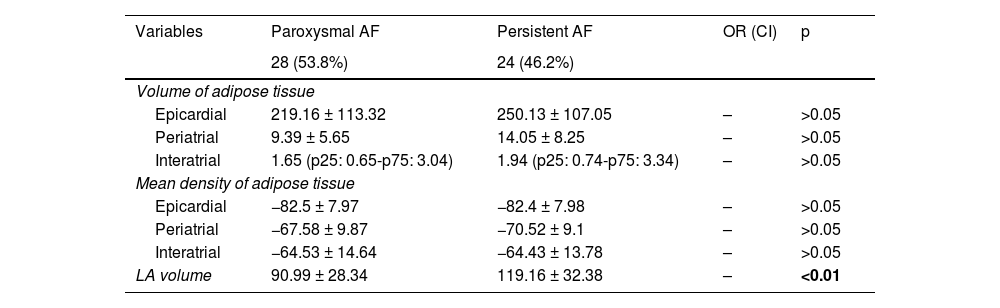

Paroxysmal vs persistent atrial fibrillationOf the 52 patients, 40 had paroxysmal AF and 12 had persistent AF. We found no significant differences between the groups in terms of age, sex, comorbidities and medications used after the ablation. The only statistically significant difference in terms of the variables obtained from the CT studies (LA volume, volume and mean density of EAT, PAT or IAT) was LA volume, which was higher in patients with persistent AF (119.16 ± 32.38 cc), compared to the rest (90.99 ± 28.34 cc) (p < 0.01) (Table 1).

Volume of left atrium and characteristics of epicardial, periatrial or interatrial adipose tissue in patients with paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation.

| Variables | Paroxysmal AF | Persistent AF | OR (CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 (53.8%) | 24 (46.2%) | |||

| Volume of adipose tissue | ||||

| Epicardial | 219.16 ± 113.32 | 250.13 ± 107.05 | – | >0.05 |

| Periatrial | 9.39 ± 5.65 | 14.05 ± 8.25 | – | >0.05 |

| Interatrial | 1.65 (p25: 0.65-p75: 3.04) | 1.94 (p25: 0.74-p75: 3.34) | – | >0.05 |

| Mean density of adipose tissue | ||||

| Epicardial | −82.5 ± 7.97 | −82.4 ± 7.98 | – | >0.05 |

| Periatrial | −67.58 ± 9.87 | −70.52 ± 9.1 | – | >0.05 |

| Interatrial | −64.53 ± 14.64 | −64.43 ± 13.78 | – | >0.05 |

| LA volume | 90.99 ± 28.34 | 119.16 ± 32.38 | – | <0.01 |

LA: left atrium; AF: atrial fibrillation.

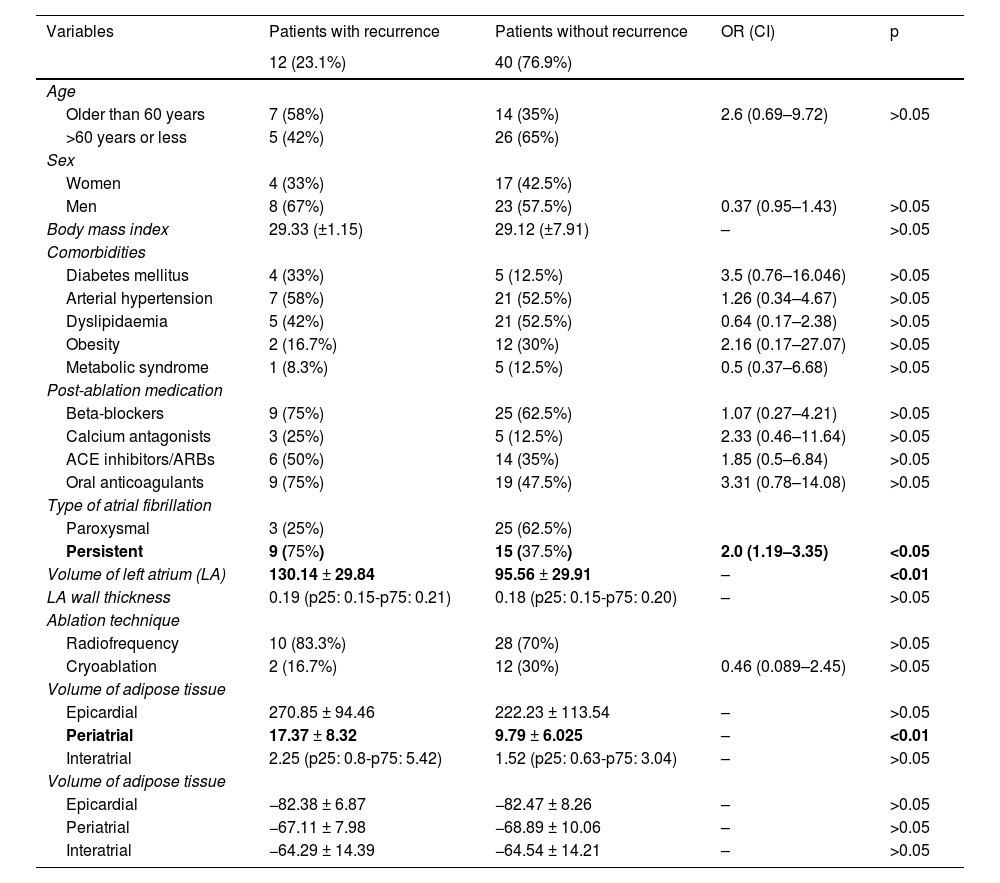

Of the 52 patients included in this study, 12 (23.1%) experienced recurrence during the follow-up period and 40 (76.9%) maintained a sinus rhythm.

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups when comparing age, sex, comorbidities, medications used, the procedure type (cryoablation vs radiofrequency ablation) and the thickness of the LA (Table 2). Of the patients with recurrence, nine (75%) had persistent AF and three (25%) had paroxysmal AF, while of the patients without recurrence, 15 (37.5%) had persistent AF and 25 (62.5%) had paroxysmal AF. The odds ratio (OR) for patients with persistent AF was 2 (1.19–3.35, p < 0.05).

Characteristics of the sample and univariate analysis in patients with and without recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation.

| Variables | Patients with recurrence | Patients without recurrence | OR (CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 (23.1%) | 40 (76.9%) | |||

| Age | ||||

| Older than 60 years | 7 (58%) | 14 (35%) | 2.6 (0.69–9.72) | >0.05 |

| >60 years or less | 5 (42%) | 26 (65%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 4 (33%) | 17 (42.5%) | ||

| Men | 8 (67%) | 23 (57.5%) | 0.37 (0.95–1.43) | >0.05 |

| Body mass index | 29.33 (±1.15) | 29.12 (±7.91) | – | >0.05 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (33%) | 5 (12.5%) | 3.5 (0.76–16.046) | >0.05 |

| Arterial hypertension | 7 (58%) | 21 (52.5%) | 1.26 (0.34–4.67) | >0.05 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 5 (42%) | 21 (52.5%) | 0.64 (0.17–2.38) | >0.05 |

| Obesity | 2 (16.7%) | 12 (30%) | 2.16 (0.17–27.07) | >0.05 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 1 (8.3%) | 5 (12.5%) | 0.5 (0.37–6.68) | >0.05 |

| Post-ablation medication | ||||

| Beta-blockers | 9 (75%) | 25 (62.5%) | 1.07 (0.27–4.21) | >0.05 |

| Calcium antagonists | 3 (25%) | 5 (12.5%) | 2.33 (0.46–11.64) | >0.05 |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs | 6 (50%) | 14 (35%) | 1.85 (0.5–6.84) | >0.05 |

| Oral anticoagulants | 9 (75%) | 19 (47.5%) | 3.31 (0.78–14.08) | >0.05 |

| Type of atrial fibrillation | ||||

| Paroxysmal | 3 (25%) | 25 (62.5%) | ||

| Persistent | 9 (75%) | 15 (37.5%) | 2.0 (1.19–3.35) | <0.05 |

| Volume of left atrium (LA) | 130.14 ± 29.84 | 95.56 ± 29.91 | – | <0.01 |

| LA wall thickness | 0.19 (p25: 0.15-p75: 0.21) | 0.18 (p25: 0.15-p75: 0.20) | – | >0.05 |

| Ablation technique | ||||

| Radiofrequency | 10 (83.3%) | 28 (70%) | >0.05 | |

| Cryoablation | 2 (16.7%) | 12 (30%) | 0.46 (0.089–2.45) | >0.05 |

| Volume of adipose tissue | ||||

| Epicardial | 270.85 ± 94.46 | 222.23 ± 113.54 | – | >0.05 |

| Periatrial | 17.37 ± 8.32 | 9.79 ± 6.025 | – | <0.01 |

| Interatrial | 2.25 (p25: 0.8-p75: 5.42) | 1.52 (p25: 0.63-p75: 3.04) | – | >0.05 |

| Volume of adipose tissue | ||||

| Epicardial | −82.38 ± 6.87 | −82.47 ± 8.26 | – | >0.05 |

| Periatrial | −67.11 ± 7.98 | −68.89 ± 10.06 | – | >0.05 |

| Interatrial | −64.29 ± 14.39 | −64.54 ± 14.21 | – | >0.05 |

There were statistically significant differences when comparing LA volume between patients who had experienced recurrence and those who had not, with higher volumes in those who had (130.14 ± 29.84 cc), compared to those who had not (95.56 ± 29.91 cc) (Table 2).

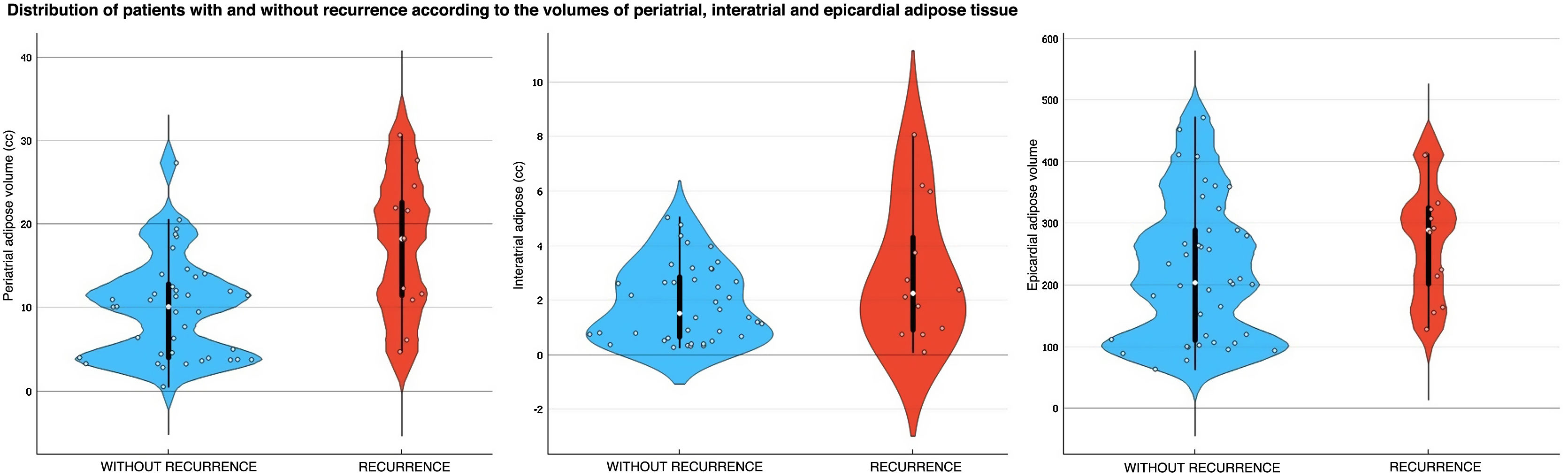

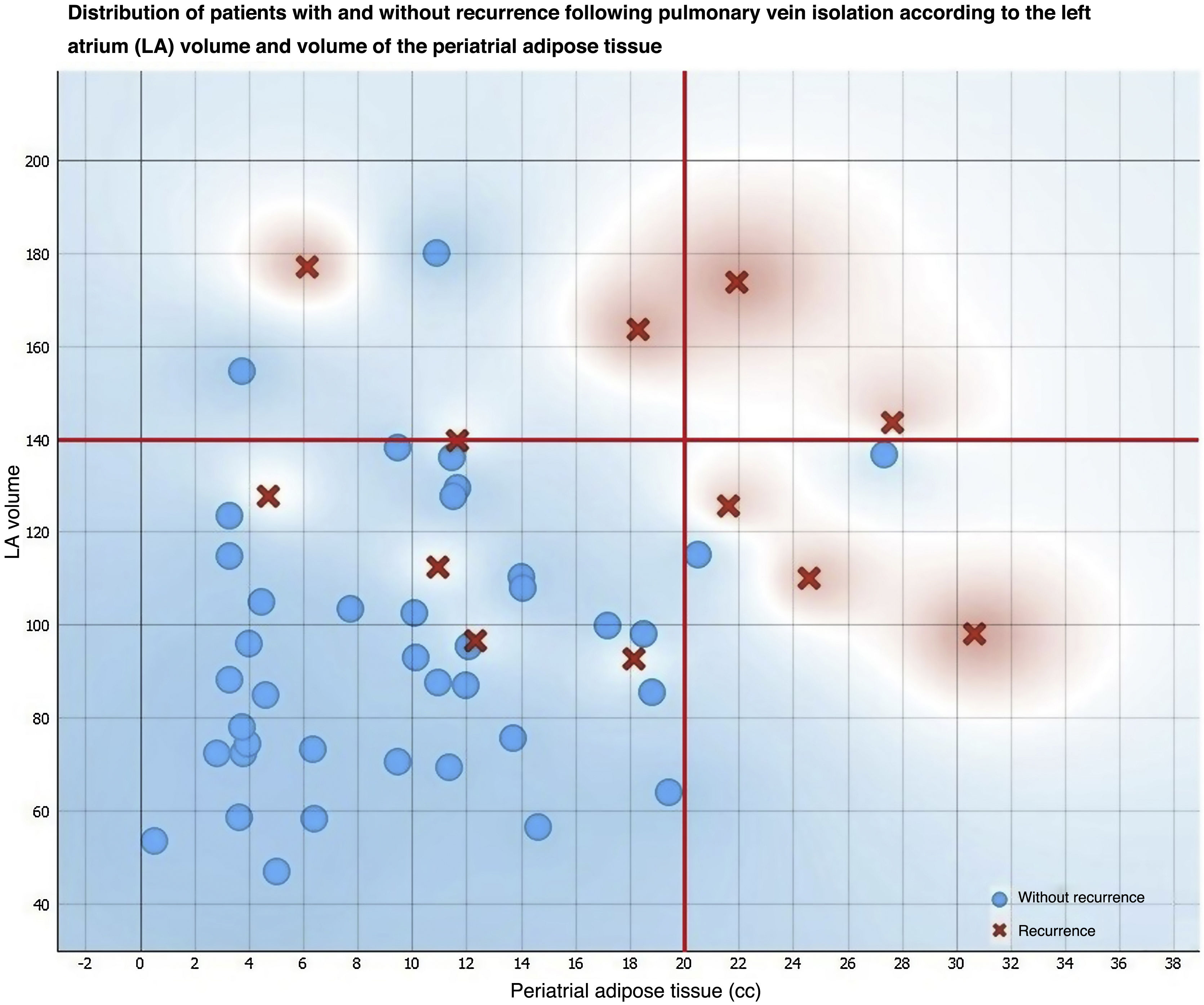

The analysis of PAT, EAT and IAT volumes revealed that the last two variables did not differ significantly between patients with and without recurrence, despite the mean values being higher in patients with recurrence compared to those without (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Significant differences (p < 0.01) were found in the PAT volume between patients with and without recurrence, with higher values in the recurrence group (17.37 ± 8.32 cc) compared to those in the non-recurrence group (9.79 ± 6.02 cc) (Figs. 2 and 3).

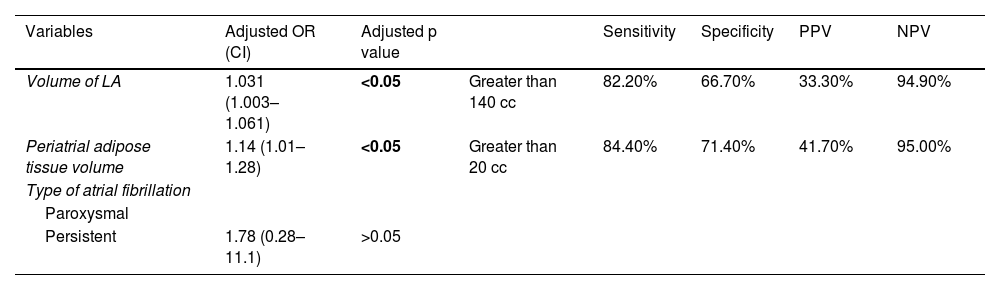

When these variables were subjected to multivariate analysis using logistic regression, statistical significance persisted for LA volume and PAT volume (p < 0.05) as risk factors for recurrence after pulmonary vein isolation (Table 3). The same variables were submitted to a second multivariate analysis using the proportional hazards model and no statistically significant differences were found in the hazard rate (p > 0.05).

Multivariate analysis and threshold values for left atrium volume and periatrial adipose tissue for the prediction of recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation.

| Variables | Adjusted OR (CI) | Adjusted p value | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume of LA | 1.031 (1.003–1.061) | <0.05 | Greater than 140 cc | 82.20% | 66.70% | 33.30% | 94.90% |

| Periatrial adipose tissue volume | 1.14 (1.01–1.28) | <0.05 | Greater than 20 cc | 84.40% | 71.40% | 41.70% | 95.00% |

| Type of atrial fibrillation | |||||||

| Paroxysmal | |||||||

| Persistent | 1.78 (0.28–11.1) | >0.05 | |||||

LA: left atrium; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

The analysis of EAT, PAT and IAT mean density revealed there were no statistically significant differences found between patients with and without recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation (Table 2).

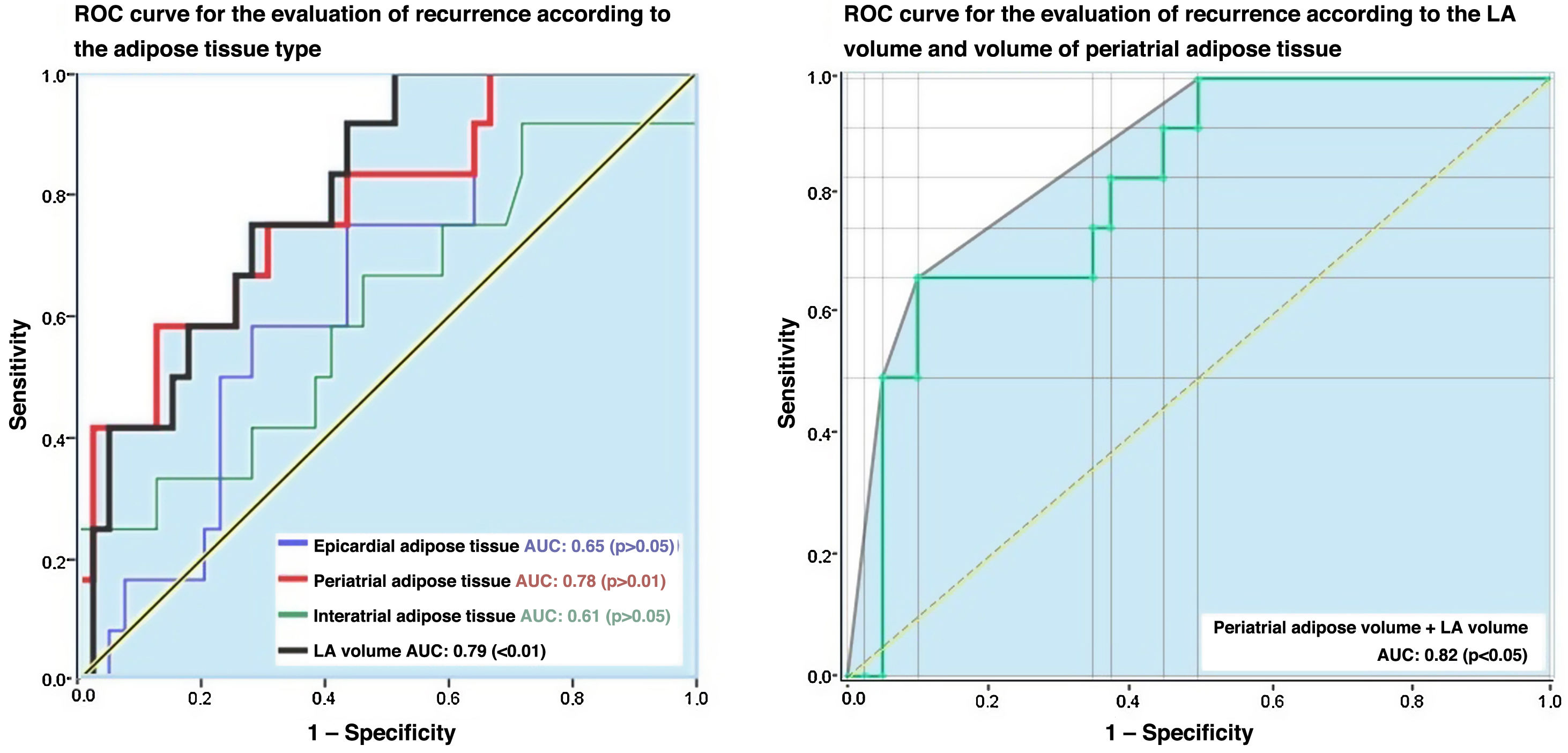

Finally, an analysis of LA and PAT volumes through the ROC curves showed that the area under the curve was 0.78 and 0.79, respectively (Fig. 4), with sensitivity values of 82.2% and 84.4% and specificity values of 66.7% and 71.4% for the prediction of recurrence in those patients who had an LA volume of more than 140 cc and a PAT volume greater than 20 cc, respectively (Table 3).

DiscussionThe main findings of this study were firstly that patients with persistent AF have higher LA volumes than patients with paroxysmal AF. Secondly, we found that among patients with persistent AF, higher LA and PAT volumes indicated a greater risk of recurrence within 3 and 12 months following pulmonary vein isolation. Meanwhile, no significant differences were found between patients with and without recurrence in terms of PAT, EAT, IAT mean density.

Previous studies have described the existence of morphological and volumetric differences in the LA according to the AF type with similar results to ours. Nagashima et al.14 found that patients with persistent and paroxysmal AF had LA volumes of 62.4 ± 37.2 and 35.9 ± 16.2 ml, respectively. LA volume was measured by echocardiography. In our study, these volumes were 115.18 cc (P25: 95.96 - P75: 139.82) and 89.96 cc (P25: 72.33 - P75: 104.6). These differences may be due to the different techniques our studies used to measure the volume. Despite this, the LA volume reported in patients with persistent AF was greater than that reported in patients with paroxysmal AF. This finding may be associated with the duration of the arrhythmia, which has been shown to contribute to the development of increased atrial wall fibrosis.19

When assessing the mean density and volumes of EAT, PAT and IAT according to AF type, we found no significant differences. However, the three tissue type volumes were at least 15% greater in patients with persistent AF compared to patients with paroxysmal AF (Table 1).

Patients with larger LAs are at greater risk of recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation.14,16–18,25–27 In the prospective study carried out by Straube et al.26 on 473 patients, they found that LA volumes greater or equal to 122.7 ml had a sensitivity of 53% and a specificity of 69% for predicting recurrence, respectively. While that study did not describe the phase of the cardiac cycle in which the volume was calculated, the results in our study are similar. In our study, LA volumes greater than 140 ml during the 75% phase of the cardiac cycle predicted recurrence with a sensitivity of 82.2% and a specificity of 66.7%. In another study,16 the LA volume calculated during the 75% phase of the cardiac cycle and adjusted for body surface area was higher in patients with recurrence, with a 3% increase in the adjusted hazard rate compared to the other patients. These findings support LA volume being a factor that influences the time to recurrence.

While most studies we have compared our results with have also used the 75% phase of the cardiac cycle, the use of other phases of the cardiac cycle could lead to different LA volumes being obtained.

There is significant heterogeneity in the methodology applied to measure the volume of the three types of adipose tissue (EAT, PAT and IAT), in terms of different radiological density thresholds and the way the obtained data is analysed. Some studies have analysed the difference in recurrence rates using multivariate proportional hazards model analysis, while others have examined the risk relationship through logistic regression at a specific cutoff point in time.

In our study, adipose tissue has been quantified using the threshold values of −15 to −195 HU, as in a previous study,27 while other authors have used other threshold values (Table 4). Using this quantification method, we found no significant differences in LA and PAT volume between patients with and without recurrence when analysed using the proportional hazards model. However, significant differences were identified when evaluated using logistic regression. This could be due to the small difference found when assessing the speed of recurrence over a short period of time.

Comparison of cardiac adipose tissue characteristics assessed in this and previous studies.

The table shows statistical significance of volume and/or mean density of different types of adipose tissue according to studies, represented as crosses for volume and circles for mean density. Each figure has a different colour according to the type of adipose tissue being studied (red for epicardial, blue for pericoronary, green for periatrial and black for interatrial).

Some studies have previously reported an independent association between the volume of EAT and the presence of earlier recurrences.13,16,17,22,24,27 In our study, we have not found any independent association of epicardial tissue enlargement with the risk of recurrence. These findings are similar to those of two other studies20,23 which have used different density limits to quantify volume (Table 4). One of these studies,23 conducted on a sample similar to ours (53 patients), found no association between recurrence and the time period of 3–30 months after ablation. Similarly, the other study20 conducted prospectively with 55 patients monitored for 12 months, also found no statistically significant differences in EAT between patients with and without recurrence.

We found that patients with larger volumes of PAT had a significantly higher risk of recurrence. These findings are consistent with some studies,21,23 while others have reported no statistically significant association.18,27 In this last group, one study27 carried out with 212 patients using the same attenuation threshold values as in our study for defining PAT (−15 to −195 HU) has analysed the hazard ratio (HR) at one year without identifying any significant differences in PAT volume between patients with and without recurrence. These findings could be impacted by the short follow-up time for detecting differences in the recurrence rate. In our case, we have not found any difference in the HR, but we have found differences in the OR at 12 months.

One previous study20 found IAT volume to be independently associated with risk of recurrence. This study used a different attenuation range (−30 to −195 HU). In our study, we did not find an increased risk secondary to a larger volume of IAT.

We also found no differences in recurrence after ablation with respect to the mean density of EAT, PAT or IAT, while other authors21 did find an association between the mean density of PAT and the risk of recurrence when using density ranges of between −50 and −190 HU. It has been posited that these findings may be due to inflammatory changes in adipose tissue involving increased oedema.

Other authors who have used a similar attenuation range18 have found no such differences in PAT density when comparing patients with and without recurrence. Nor were differences between these two groups found when using ranges closer to zero, as in our study (−15 to −195 HU) and another.27

One of the limitations of our study is the manual segmentation of EAT, PAT and IAT volume, as there may be differences when assessed by another observer. While we have not analysed these differences in our study, a previous study has found an excellent interobserver correlation (0.99) when using similar manual segmentation techniques. Another potential limitation of our study is the use of different attenuation ranges compared to other studies. We could not find any reference study that correlates adipose tissue volume measured by pathological examination with that found on imaging, specifically CT. However, it has been mentioned that values of −30 to −195 HU represent adipose tissue free of other types of soft tissues, such as connective tissue.28 Regarding the measurement of cardiac adipose tissue volume, we have not found any studies that compare the relative quantities obtained in the different phases of the cardiac cycle, which could constitute a limitation if there were differences. Finally, the sample size of our study may have limited our ability to evaluate certain variables from CT scans, such as EAT, PAT, and IAT volume. While no significant differences were found, these variables did not fully overlap in a portion of patients. Expanding the sample size could help reveal such differences.

ConclusionIn our setting, AF type, both increased LA volume and PAT volumes are risk factors for recurrence in patients with AF undergoing pulmonary vein isolation, whether by cryoablation or radiofrequency ablation. Conversely, mean IAT, PAT and EAT density does not differ between patients with and without AF recurrence.

CRediT authorship contribution statement- 1

Research coordinators: JJAJ.

- 2

Study concept: JMCG.

- 3

Study design: JMCG, JJAJ, AUV.

- 4

Data collection: JMCG, MJGB, HTB.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: JMCG, JJAJ, AAC.

- 6

Data processing: JMCG

- 7

Literature search: AAC, JMCG.

- 8

Drafting of article: JMCG, AAC, JJAJ.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: JJAJ.

- 10

Approval of the final version: JJAJ.