Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders (with increasing order of the depth of invasion: accreta, increta, percreta) are quite challenging for the purpose of diagnosis and treatment. Pathological examination or imaging evaluation are not very dependable when considered as stand-alone diagnostic tools. On the other hand, timely diagnosis is of great importance, as maternal and fetal mortality drastically increases if patient goes through the third phase of delivery in a not well-suited facility. A multidisciplinary approach for diagnosis (incorporating clinical, imaging, and pathological evaluation) is mandatory, particularly in complicated cases. For imaging evaluation, the diagnostic modality of choice in most scenarios is ultrasound (US) exam; patients are referred for MRI when US is equivocal, inconclusive, or not visualizing placenta properly. Herewith, we review the reported US and MRI features of PAS disorders (mainly focusing on MRI), going over the normal placental imaging and imaging pitfalls in each section, and lastly, covering the imaging findings of PAS disorders in the first trimester and cesarean section pregnancy (CSP).

Los trastornos del espectro de placenta acreta (EPA) (en orden ascendente en función de la profundidad de la invasión: acreta, increta y percreta) plantean un desafío diagnóstico y de tratamiento. El examen patológico o la evaluación por técnicas de diagnóstico por imagen no son muy fiables si se consideran como herramientas diagnósticas independientes. Sin embargo, un diagnóstico temprano es de gran importancia, ya que la mortalidad materna y fetal aumentan de forma drástica si la paciente se encuentra en unas instalaciones inadecuadas en la tercera fase del parto. Es imperativo adoptar un enfoque multidisciplinario para el diagnóstico (que incorpore la evaluación clínica, por imagen e histopatológica), en particular en los casos con complicaciones. Para la evaluación mediante imagen, la modalidad diagnóstica de preferencia en la mayoría de los escenarios es la exploración mediante ecografía; las pacientes son derivadas para la resonancia magnética (RM) cuando los resultados de la ecografía son ambiguos, no concluyentes o no permiten una visualización adecuada de la placenta. Este artículo repasa las características ecográficas y de RM de los trastornos del EPA (centrándonos principalmente en la RM), examinamos las imágenes placentarias normales y los puntos débiles de las técnicas de diagnóstico por imagen en cada sección. Por último, comentamos los hallazgos de imagen de los trastornos del EPA en el primer trimestre. Por ultimo comentaremos los hallazgos de imagen de los trastornos del EPA en el primer trimestre y en la cicatriz de cesárea anterior.

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders are a group of serious and potentially morbid conditions, with their incidence on a steady rise over the past decades.1 According to the literature, the growing number of reported PAS disorders parallels the increased rate of cesarean deliveries (the main predisposing factor).1 The second main risk factor is placenta previa (placental tissue overlying the internal os of the cervix to any extent), as implantation in the lower uterine segment over cesarean section (C/S) scar (where decidua is deficient) will compound the risk.

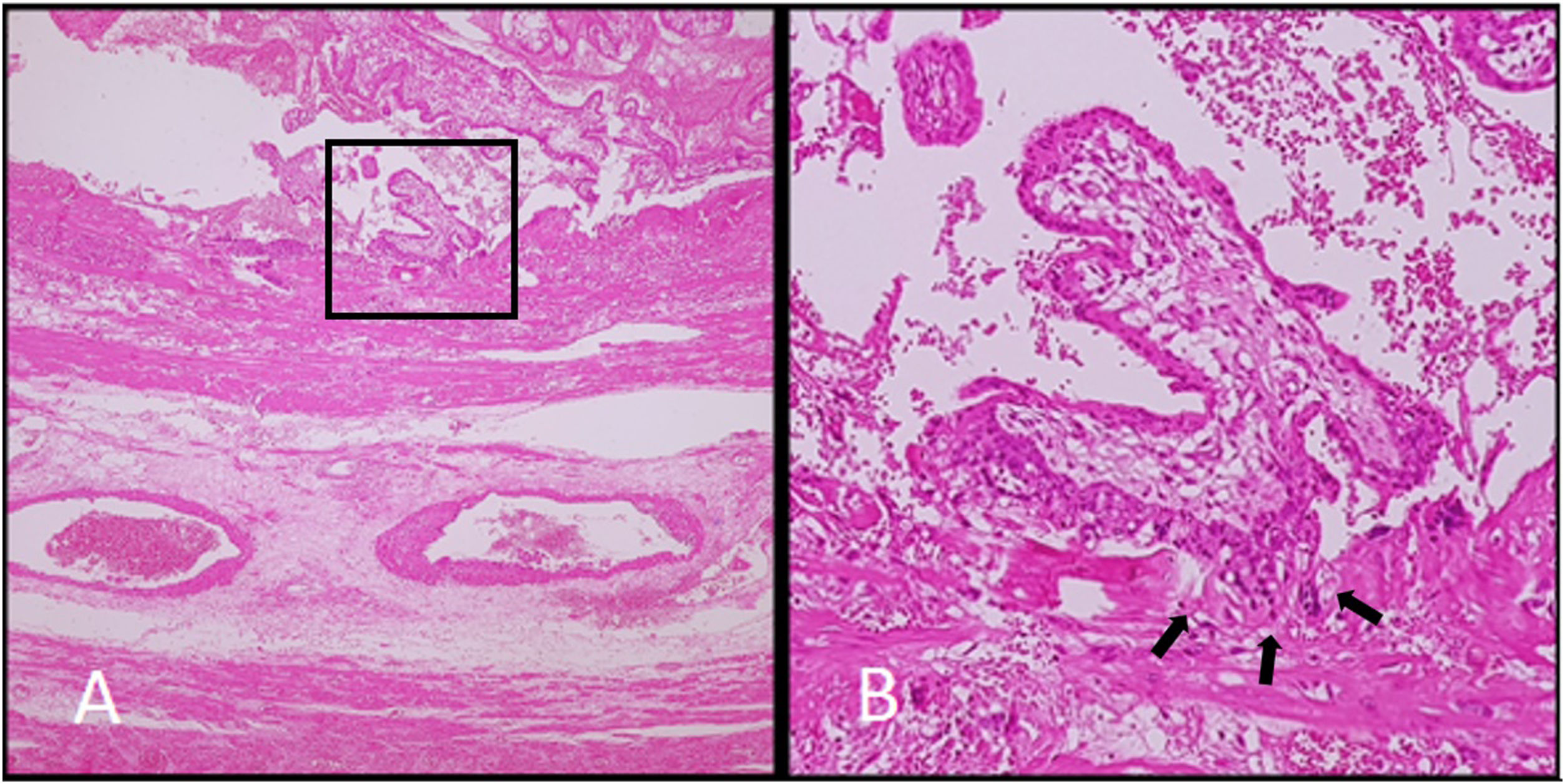

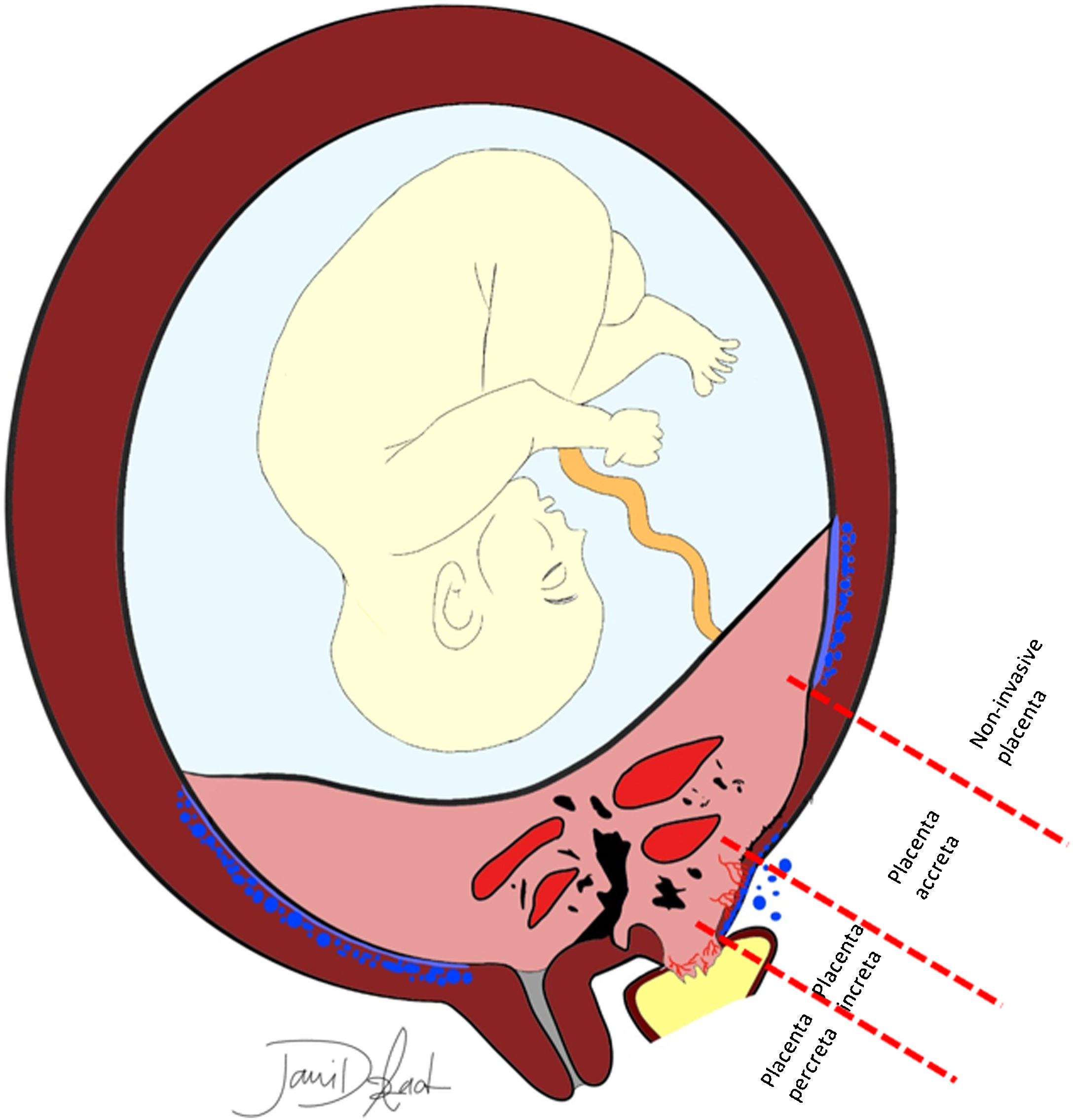

PAS disorders are further divided in two groups, (a) abnormally adherent placenta (placenta accrete vera), and (b) invasive placenta (placenta increta and percreta).2 However, some authors disagree using the term placental invasion, as extra-villous cytotrophoblasts invasion into the maternal endometrium is a normal process; in this regard, under-invasion is related to pre-eclampsia, and over-invasion will lead to PAS disorders (the preferred term). PAS disorders result from a defect in the decidua basalis, where the chorionic villi invade the myometrium.3 Normally, decidua basalis separates the chorionic villi from the myometrium, and contracting myometrium leads to unhindered and clean detachment of the placenta. Placenta accrete vera, the least invasive and most common form of PAS disorders, is abnormal fixation of the placenta directly onto the myometrium without intervening decidua basalis, while in placenta increta, placenta partially penetrates the myometrium (not reaching to the uterine serosa). In placenta percreta, the least common and most invasive form, chorionic villi invade the myometrium to the full thickness (Fig. 1) and may even extend into the surrounding organs.4–7

A 28-year-old woman at 15 weeks, presenting with ectopic pregnancy with gestational sac implanted in rudimentary corn of uterus and placenta increta. A, B. Low and high-power field photomicrograph of a histologic section of placenta showing full-thickness myometrial invasion by chorionic villi.

Antenatal and timely diagnosis of PAS disorders could be life-saving and greatly increases the chance of uneventful delivery. With delayed diagnosis, and thus, underprepared delivery, the clean detachment of the placenta from the uterus during the third phase of delivery fails, and at the time of placental separation, hemorrhage, shock, multisystem organ failure, infectious morbidities, coagulation disorders, and postoperative thromboembolisms remarkably increase the risk of peri- and postpartum morbidity and mortality.8

On the other hand, PAS disorders may cause many complications prior to delivery, examples of which are damage to local organs, such as the bladder, ureters, and bowel.7,9 Antenatal evaluation of the degree and topography of the placental invasion to myometrium is also invaluable, as they are directly associated with intra- and postsurgical outcomes10,11; additionally, placental invasion topography guides the surgical team to define the most appropriate method and trajectory for proximal vascular control.12

Herewith, we will review the reported US and MRI features of PAS disorders going over the normal placental imaging and imaging pitfalls, and lastly, we will discuss the imaging findings in PAS disorders in the first trimester.

Imaging evaluation of placenta for PASUltrasound exam (through transabdominal and transvaginal probing) is still imaging modalities of choice for evaluating the placenta. MRI is considered as a supplementary imaging technique. Both pathology and imaging (US and MRI) are posed to challenges to determine the presence and extent of invasion in PAS disorders (especially focal and less severe forms of invasion).9,13,14 However, differentiating between placenta accreta vs. increta is of no clinical importance, as the treatment plan is the same. On the other hand, in placenta percreta, chorionic villi invade adjacent structures (e.g., bladder, rectosigmoid, pelvic sidewall) that affect surgical planning and should be identified. This extrauterine abnormal placentation would be detectable in MRI with a better accuracy than US.

Fig. 2 summarizes the common features of PAS. Unfortunately, none of the US or MR imaging features of accreta spectrum, in isolation or even in combination, can confidently predict the depth of invasion.15

A schematic presentation of different depths of placental invasion in PAS. Placenta previa and previous cesarean delivery are the most common risk factors. Decidua basalis (the continuous band of cerulean blue color) is deficient in areas with PAS. Make a note of bizarre high-flow intraplacental lacunae, myometrial thinning and heterogenicity, irregularity of the placental–myometrial interface, loss of retroplacental clear space, and fibrotic band with subjacent placental recess. In placenta previa (most invasive form), placental tissue may reach out to the bladder lumen. Subserosal hypervascularity, bladder vessel sign, and parametrial vessel sign are also evident.

Currently, 2-D greyscale imaging, 2-D color Doppler ultrasound, and 3-D power Doppler ultrasonography are techniques recommended for detecting PAS disorders, despite its operator reliability and relatively high reported inter-observer variation.16,17

Normally, placenta is relatively uniform in thickness and echogenicity, with 2–4 cm thickness in the midportion (becomes thicker as pregnancy advances), smooth external contour, and gradually tapered edges. In second-trimester, placenta is homogenous, granular, and hyperechoic compared to the underlying rim of thin, well-defined, and hypoechoic myometrium.

Maternal veins drain the blood from the intervillous space and run parallel to the decidua, forming the ‘retroplacental echolucent zone’ in the US imaging of the normal placenta.18 The recommended gestational age for performing ultrasonography is between 18–20 weeks (the time of second routine US scan).4,19

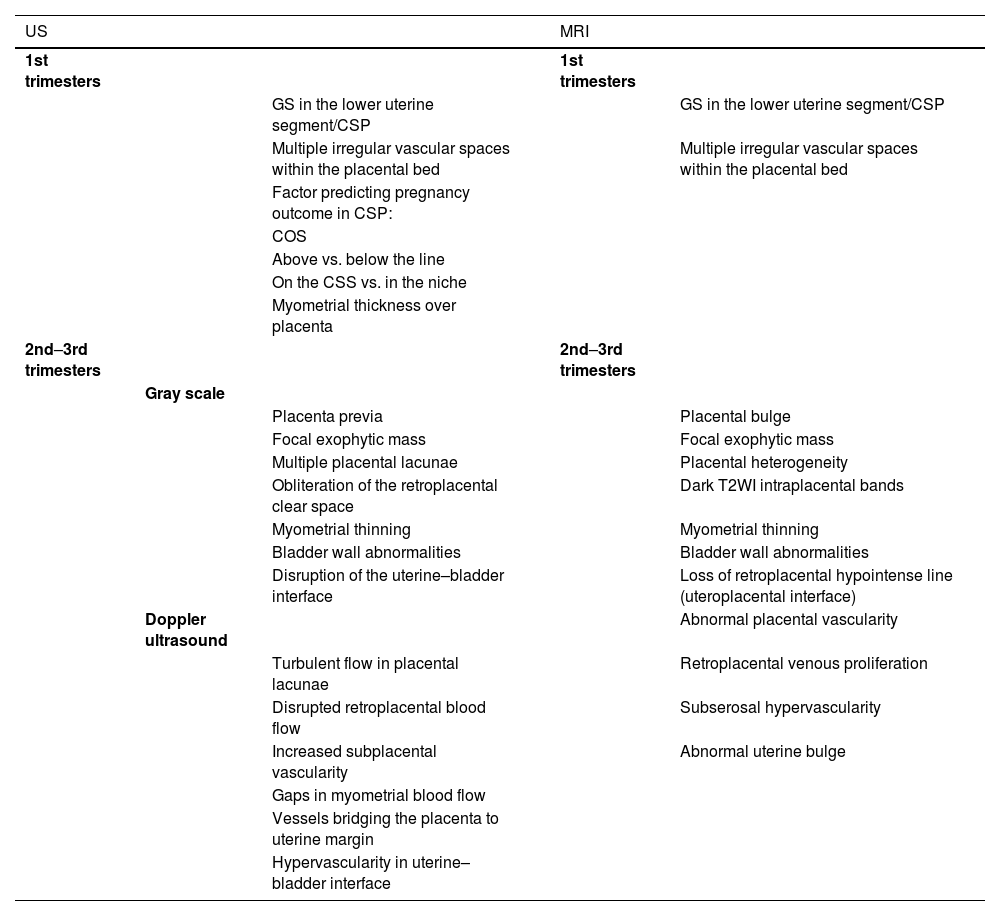

Table 1 shows common US and MRI features of the PAS reported in literature, as well as imaging techniques/sequences recommended for PAS evaluation.

Imaging (US and MRI) features of PAS disorders in early pregnancy and 2nd–3rd trimesters, and recommended modalities/sequences.

| US | MRI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st trimesters | 1st trimesters | |||

| GS in the lower uterine segment/CSP | GS in the lower uterine segment/CSP | |||

| Multiple irregular vascular spaces within the placental bed | Multiple irregular vascular spaces within the placental bed | |||

| Factor predicting pregnancy outcome in CSP: | ||||

| COS | ||||

| Above vs. below the line | ||||

| On the CSS vs. in the niche | ||||

| Myometrial thickness over placenta | ||||

| 2nd–3rd trimesters | 2nd–3rd trimesters | |||

| Gray scale | ||||

| Placenta previa | Placental bulge | |||

| Focal exophytic mass | Focal exophytic mass | |||

| Multiple placental lacunae | Placental heterogeneity | |||

| Obliteration of the retroplacental clear space | Dark T2WI intraplacental bands | |||

| Myometrial thinning | Myometrial thinning | |||

| Bladder wall abnormalities | Bladder wall abnormalities | |||

| Disruption of the uterine–bladder interface | Loss of retroplacental hypointense line (uteroplacental interface) | |||

| Doppler ultrasound | Abnormal placental vascularity | |||

| Turbulent flow in placental lacunae | Retroplacental venous proliferation | |||

| Disrupted retroplacental blood flow | Subserosal hypervascularity | |||

| Increased subplacental vascularity | Abnormal uterine bulge | |||

| Gaps in myometrial blood flow | ||||

| Vessels bridging the placenta to uterine margin | ||||

| Hypervascularity in uterine–bladder interface |

COS, cross over sign; CSP, cesarean section pregnancy; CSS, cesarean section scar; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasonography.

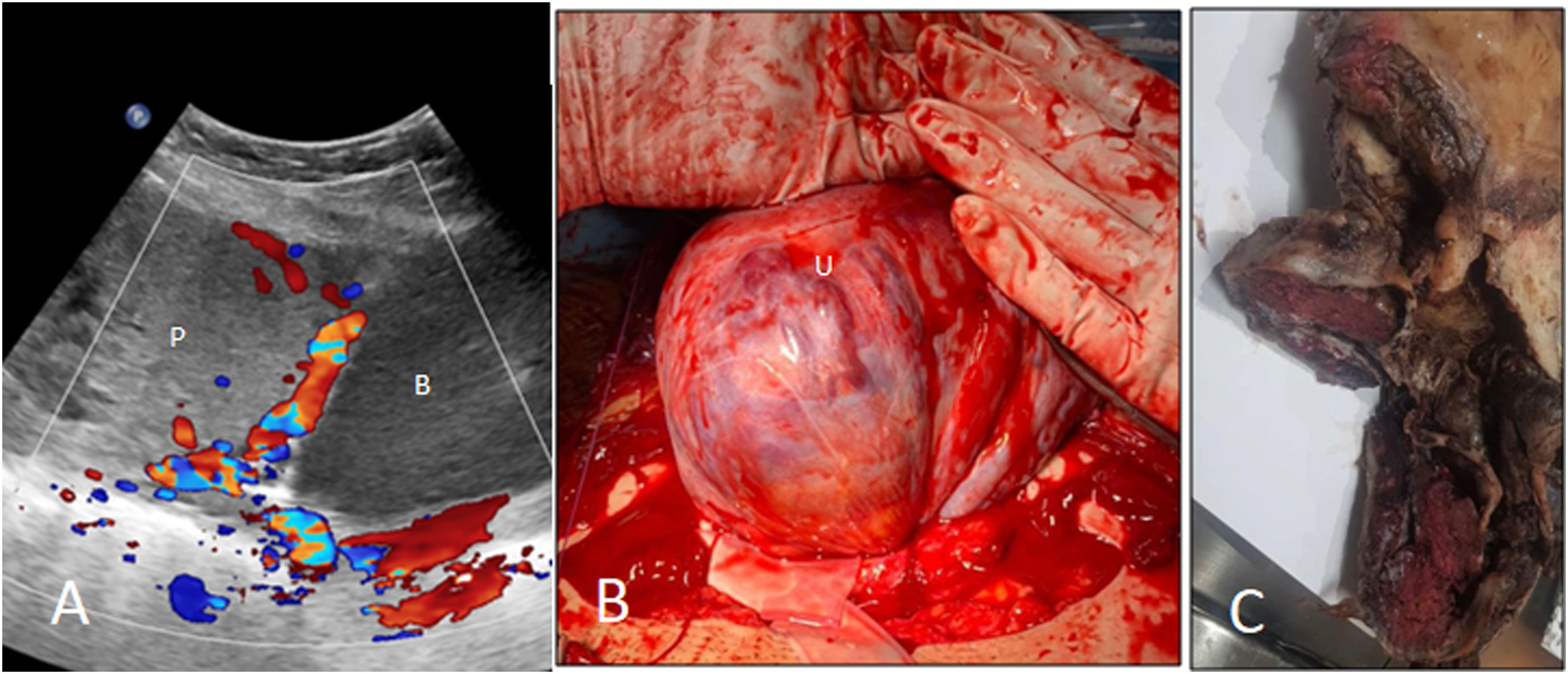

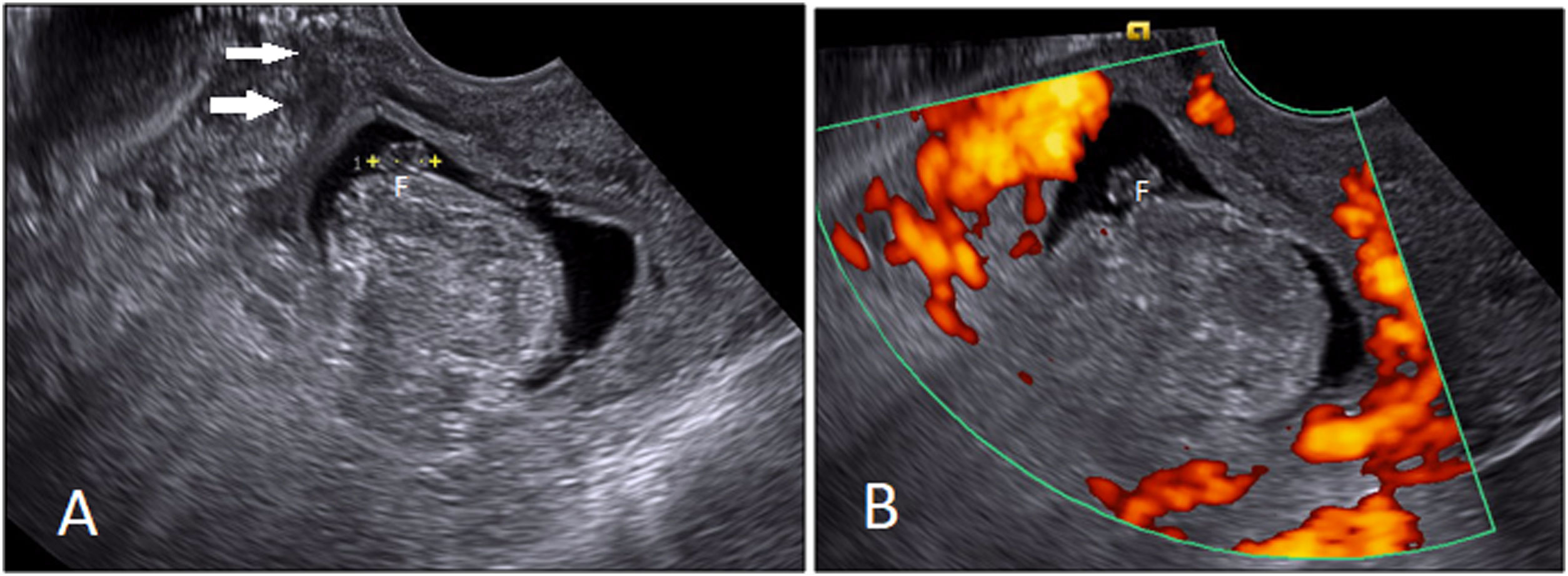

Accompanying placenta previa dramatically increases the risk of PAS disorder and should elicit a detailed examination for accrete spectrum, including transvaginal examination, Doppler imaging, and were applicable, three-dimensional power Doppler exam (Fig. 3).

A 42-year-old woman at 37 weeks with placenta percreta. A. Ultrasound is showing placenta (P) previa and abnormal placentation with placental tissue invading into the lower segment of uterus, on the cesarean scar. Multiple intraplacental bizarre-shaped lacunae are seen in placenta. Urinary bladder (B). B. Intraoperative view showing the uterine (U) serosa covered by dilated, tortuous, and disorganized vessels. C. Gross pathology specimen showing full-thickness myometrial invasion by placental tissue.

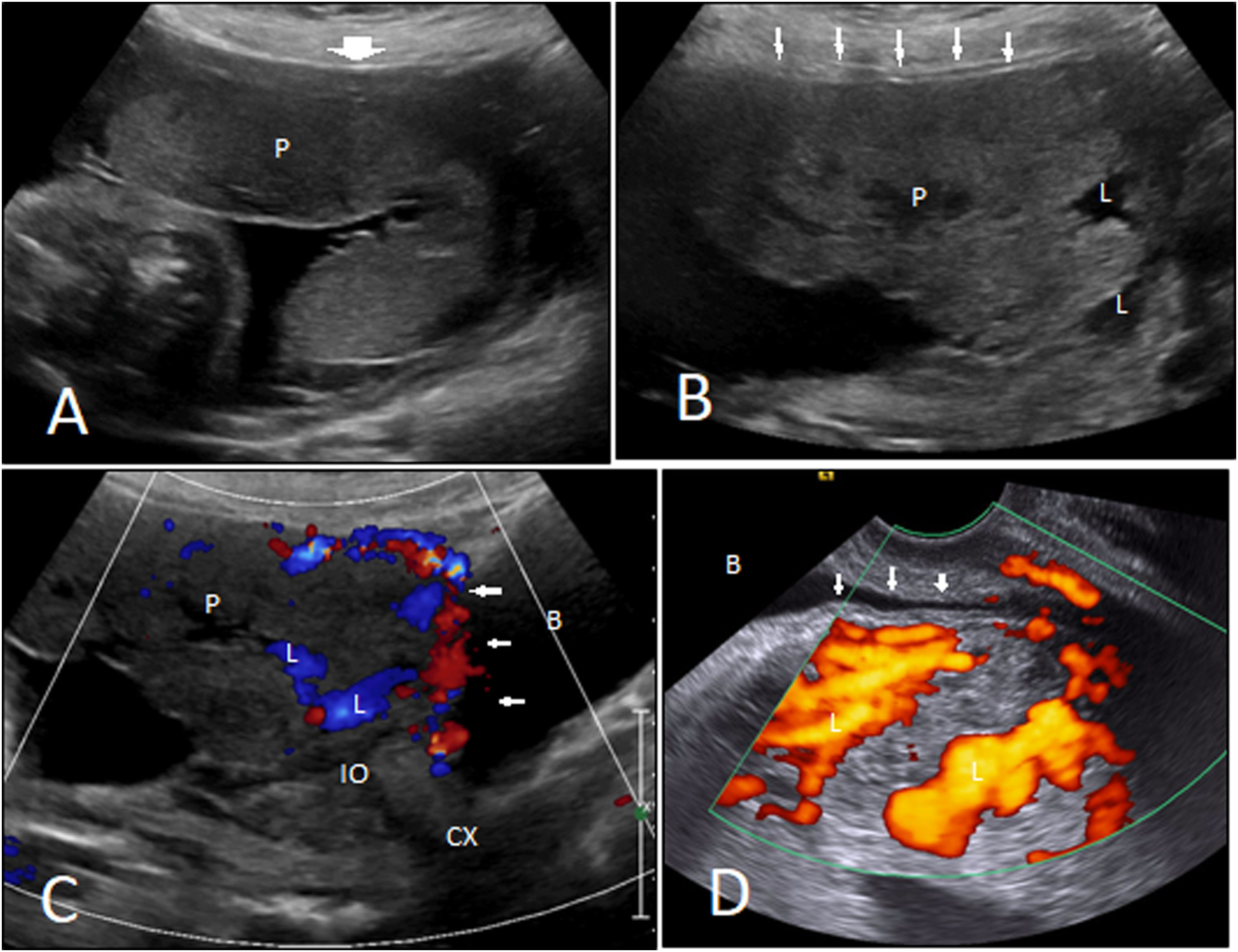

It is presented as a focal exophytic mass of placental echogenicity, mostly located anteriorly, near to the bladder, or laterally, extending to the parametrium (Fig. 4A and B).10 This US feature is of a very low sensitivity (10%) but is highly specific (99%) for detecting placenta percreta (absent in placenta accreta or increta).20 Adjacent bladder tenting will further increase the specificity.10

Ultrasound features. A 37-year-old woman at 28 weeks with placenta percreta. A, B. Normal myometrial thickness (wide arrow) in the superior part of the uterus, very thin myometrium (small arrows), and placental (P) invasion into the lower part of the uterus on the cesarean scar are seen. Multiple lacunae (L) are also noted. Placenta has covered the cervical internal os (IO). C, D. Transabdominal and transvaginal Doppler ultrasound depict increased vascularity along the placental–myometrial interface that has extended into the bladder wall (small arrows). Blood flow was detected in the lacunae (L). Bladder (B); cervix (Cx).

This feature is of great importance in the third trimester and results from long-term exposure to a pulsatile blood flow and secondary placental tissue alterations.4 Intraplacental lacunae are vascular spaces of varying size and shape within the placenta, giving it a “Swiss cheese” appearance (Fig. 4A and B). They are often parallel linear in shape and extend from the placenta into the myometrium. They are indistinct in border and show internal turbulent flow (Fig. 4C and D), as opposed to the vascular lake in third-trimester non-invasive placenta, which is more rounded in shape with a laminar flow. This feature, along with abnormal color Doppler imaging patterns, has been reported as the most sensitive US findings for diagnosing accreta (particularly when multiple lacunae in the second trimester are found), capable of detecting PAS within as early as 15 weeks.4,21–24 When there are multiple (especially ≥4) lacunae, the detection rate for placenta accreta remarkably increases (100% according to an investigation).24

Loss of the retroplacental clear spaceObliteration of the retroplacental hypoechoic zone is angle-dependent and has also been seen in non-invasive placentas, not being significantly predictive of PAS and with a high rate of false positivity (21% or more) according to some investigations.4

Myometrial thinningAnterior myometrial thickness (measured between the echogenic uterine serosa and the retroplacental clear space) of <1 mm is another grayscale sign of PAS in US; although, it has been difficult to replicate even in transvaginal ultrasonography (Fig. 4A and B).4 Twickler et al. reported this feature in all studied cases, but other studies didn’t confirm this finding and found the myometrial contour more dependable than the myometrial thickness.25

Bladder wall abnormalitiesThis feature has been related to placenta percreta, with or without disruption of or increased hypervascularity at uterine serosa–bladder interface.4,20,23 Normally, uterine serosa–bladder interface presents as a wide, thin, and smooth echogenic line with no detectable vascularity in Doppler ultrasound exam. Disruption, irregularity, thickening, and increased vascularity of the interface, or bulging of the placenta into the posterior wall of the bladder all predict placenta percreta with high sensitivity and specificity.21,23

Abnormal Doppler imaging patternsEvaluating abnormal flow patterns can help in the diagnosis of PAS disorders, especially when grayscale exam is inconclusive. Transvaginal probing may highlight the areas of hypervascularity and add diagnostic value to the color Doppler ultrasound exam.26 Shih et al. tested 3-D power Doppler imaging accuracy for detecting PAS disorders. According to their study, parameters like increased intraplacental vascularity, increased vascularity at bladder–uterine serosa interface (Fig. 4C and D), intervillous circulations, and vascular chaotic branching and tortuosity are all predictive of PAS disorders with decent accuracies.20

In a study turbulent flow in the lacunae within placental parenchyma was recorded in all patients with PAS disorder.25 Assessing the retroplacental blood flow may add information to grayscale evaluation of retroplacental clear space. In an investigation, obliteration/disruption of the normal continuous color flow pattern with a gap in myometrial blood flow was noted in all cases with PAS disorder.4 Numerous dilated/varicose periuterine blood vessels may predict extrauterine chorionic villi invasion (placenta percreta), although it can be seen in milder forms of PAS as well, and has been linked to the expression of the endothelial growth factors (Fig. 5).4 Increased subplacental vascularity, bridging vessels coursing across the placenta and reaching out to the uterine margin, and subserosal hypervascularity (Fig. 3) are other PAS prognosticators in color/power Doppler ultrasound evaluation.23,27

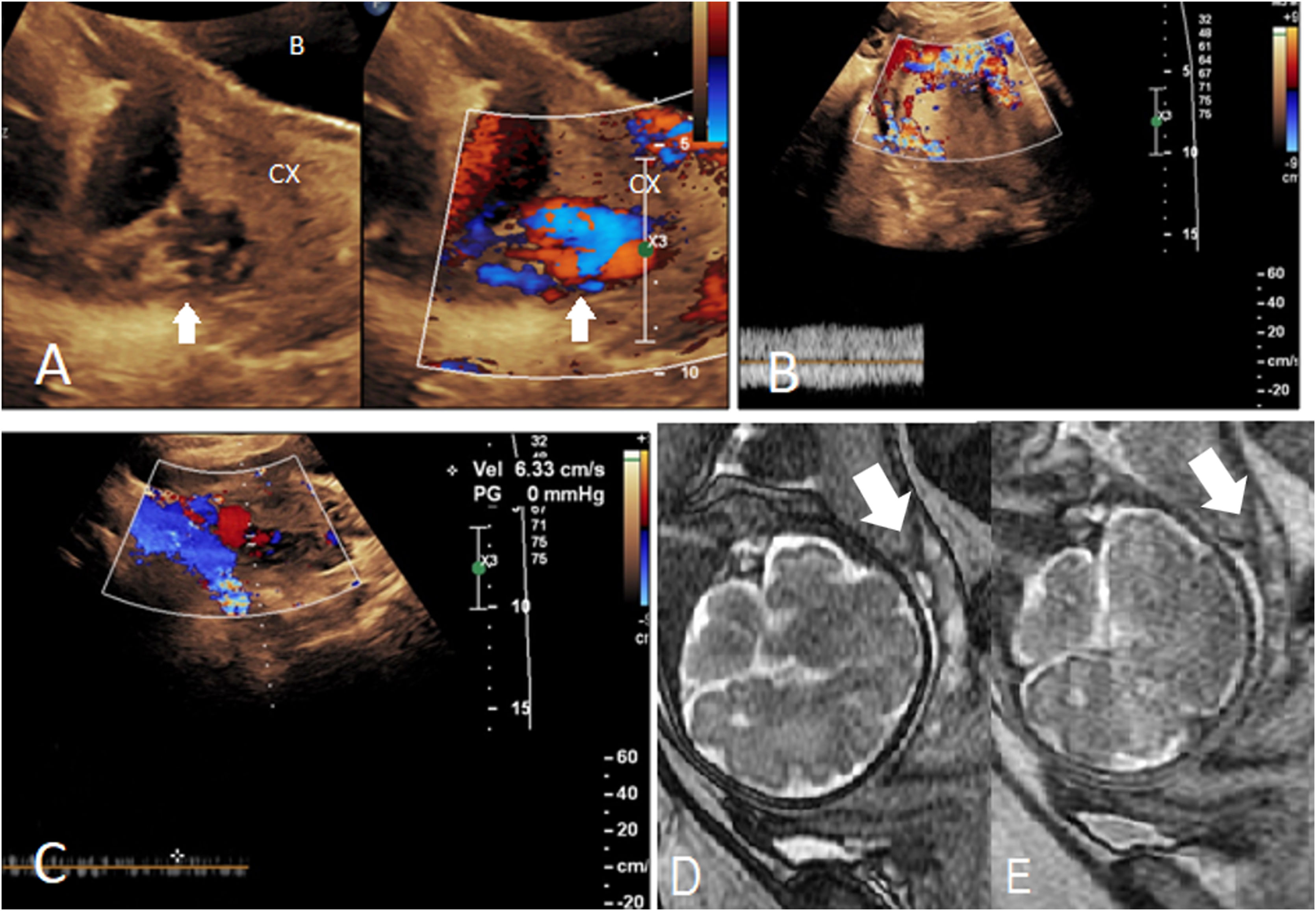

Low-lying posterior placenta and cervical varix suspected for accreta in a patient with a history of posterior myomectomy. A. Numerous tortuous and disorganized branching echolucencies in the posterior lip of cervix (Cx), with a bright color signal of flow in Doppler study. B, C. Peak systolic velocity of the retroplacental veins (of fetal origin) was averagely about 25 cm/s (B), which was higher than that of these tortuous veins in the cervix (C) (6.3 cm/s). D, E. SSFP (D) and SSFSE (E) sequences show a normal non-invasive placenta, with homogenous intermediate signal in SSFSE, without T2 dark bands, and with normal overlying myometrial thickness. Tortuous high-flow vessels (with flow-related signal in SSFP) are noted in the posterior cervical lip. Cervix (Cx).

When US exam is suspicious or inconclusive, in cases of the posterior placenta where US beams cannot reach out to the placenta appropriately, or when severe placenta percreta is suspected on US (to determine the extrauterine spread of the placenta), placental MRI comes into play.1,23,27,28 When US offers a definitive diagnosis, MRI (if performed) would be often undertaken for surgical planning (C/S delivery and peripartum hysterectomy).

MRI offers further detail on the uteroplacental interfaces and the surrounding periuterine environment, which is far more difficult to be evaluated in US exam. As mentioned previously, it is also valuable in surgical planning; nonetheless, it should never be the one and only antenatal diagnostic test relied on. Nevertheless, according to a study by Einerson et al., MRI have a chance of making an overdiagnosis in up to 14% of cases, with a false negativity of nearly 7%. MRI sequences with high temporal resolution and reasonable contrast-to-noise ratios are key sequences for placental imaging. To maximize the signal-to-noise ratio, an external multichannel surface phased-array coil is used whenever possible.6,9,29 In obese patients and later in pregnancy, a body coil may be employed. Parallel imaging is beneficial and should be implemented when possible, as it enhances the image sharpness and decreases the specific absorption rate.9

The recommended practice is to take sequences orthogonal to the area of placental implantation, in addition to images taken orthogonal to the maternal pelvis for evaluating the cervix and bladder. The former might be very difficult to fulfill, as numerous configurations for placenta implantation can be assumed, and it often involves more than one side of the uterus.30 Images are advised to be acquired in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes (with respect to the uterus) to cover all areas of the placental–myometrial interface, with a slice thickness of ≤4 mm.29,31 Some experts recommend additional set of images taken with regard to the placental–myometrial interface (including oblique axial plane: perpendicular to placental–myometrial interface).29 Recommended MRI sequences for diagnosing PAS include: (a) T2-weighted single-shot fast (turbo) spin-echo images (SSFSE) to evaluate the uterine layers and placental architecture, (b) T1-weighted gradient-echo sequences with fat suppression, to identify intra- or retroplacental hematoma if placental abruption is a concern.29 T2-weighted fat-suppressed sequences are not recommended for evaluating PAS.4

Recent studies have stated that contrast agents are not required in evaluating patients suspected of PAS; moreover, fetus may swallow the contrast agent that has crossed the placental membranes and entered the amniotic fluid, where its half-life and adverse effects are yet unknown.29,32 A large-scale cohort study reported an increased rate of rheumatological, inflammatory, infiltrative conditions after using paramagnetic contrast at any gestational age, as well as stillbirth or neonatal death.33 Nonetheless, some facilities use gadolinium-based contrast agents in certain cases for surgical planning (in such cases, patients are scheduled for delivery shortly after MRI).4,21

Steady-state free precession (SSFP) reduces the breathing artifacts, accentuates the appearance of the placental vessels and lakes, and differentiates true vessels from other sources of low T2 signal intensity when compared to SSFSE in a side-by-side manner through their “bright blood” and “dark blood” characteristics, respectively (Fig. 5D and E).30,32

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) can discernibly differentiate the placenta from myometrium, outlining the border between the placenta and underlying myometrium, as well as aiding in the detection of a hematoma (Fig. 6F and G).34

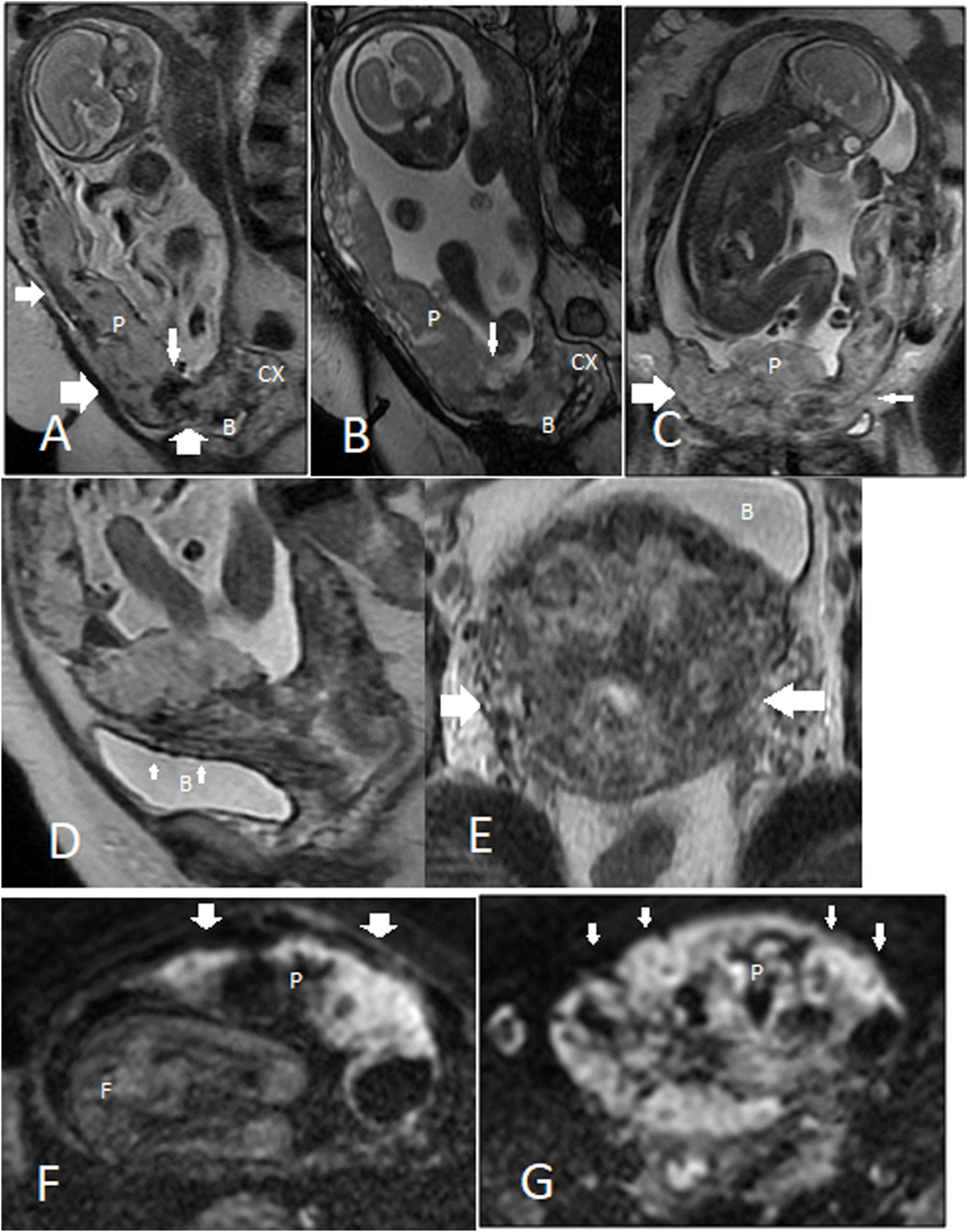

MRI features. A 31-year-old woman at 24 weeks with placenta percreta. A–C. Placenta previa with heterogeneous signal in T2-weighted image is appreciated; T2-dark bands (narrow vertical arrow) are more conspicuous in the SSFSE sequence (A) compared to SSFP sequence (B). Subplacental hypervascularity (wide vertical arrow in A), placental bulge (wide horizontal arrow in A and C), normal T2-hypointense placental–myometrial interface (narrow horizontal arrow in A), myometrial thinning (narrow horizontal arrow in C), and placental tissue protruding into the bladder lumen (B) are all shown. D, E. Extrauterine extension. Large flow voids in the bladder wall (bladder vessel sign, small arrows in D) imply bladder wall invasion, and parametrial vessel sign (large arrows in E) suggests parametrial invasion. F, G. DWI clearly outlines the border between the placenta and myometrium, as placenta shows a very high signal intensity in diffusion imaging. Compare areas with normal myometrial thickness (F) to areas of significant myometrial thinning (G). Placenta (p); bladder (B); cervix (Cx).

On the maternal surface of the normal placenta, placental septa (thin connective tissue planes) surround the cotyledons and can manifest as subtle thin bands of low T2 signal intensity.35 Normally, placenta shows imaging evidence of senescence across pregnancy that imaging interpreters should be aware of; otherwise, it can lead to misdiagnosis of PAS disorders in cases of normal non-invasive placentation. As the placenta ages (mainly in the third trimester), it becomes heterogenous primarily due to small foci of calcification, micro-hemorrhages, and lacunae, that presents as heterogenicity in signal intensity (especially in T2 weighted and susceptibility images). Authors mostly recommend 24th–30th (or according to some papers 28th–32th) week of gestation for performing MRI.19,29,32 At this age, placenta shows a uniform intermediate signal and is commonly distinct from the heterogeneous three-layer myometrium. Myometrial layers include a middle layer (hyperintense relative to the placenta) sandwiched between dark inner and outer layers. The middle layer becomes more hyperintense as pregnancy progresses.4

At the site of cord insertion, the umbilical arteries and vein give rise to subchorionic vessels, which run along the fetal surface of the placenta while dividing into smaller branches that dip into the placenta in a perpendicular fashion. Some of these chorionic vessels might raise suspicion on PAS due to their vertical course, but they generally are lower in number, imperceptible in the deeper placenta, and smaller in caliber (≤5 mm). Therefore, visualizing larger vessels at the cord insertion and in subchorionic distribution are considered normal, while large intraplacental vessels could herald PAS disorders.30 Moreover, myometrial (subplacental) flow voids could be seen in MRI of the non-invasive placenta and represent maternal spiral arteries that run perpendicular to the decidua surface at the myometrium-placenta interface.6,19

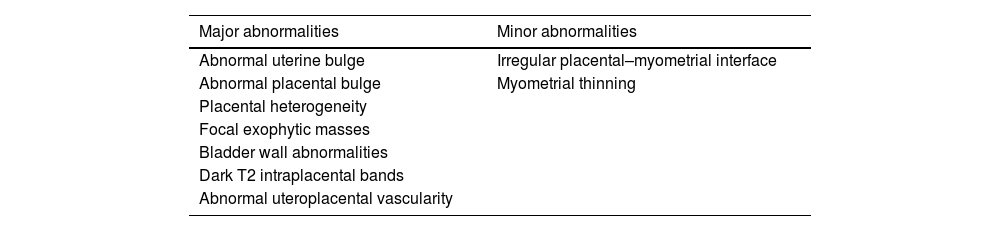

PAS-related MRI findings are divided into two main classes (Table 2): major abnormalities (when specificity of the finding is >80%), and minor abnormalities (if the specificity of the finding falls below 80%).32

Major and minor PAS-related MRI findings.

| Major abnormalities | Minor abnormalities |

|---|---|

| Abnormal uterine bulge | Irregular placental–myometrial interface |

| Abnormal placental bulge | Myometrial thinning |

| Placental heterogeneity | |

| Focal exophytic masses | |

| Bladder wall abnormalities | |

| Dark T2 intraplacental bands | |

| Abnormal uteroplacental vascularity |

In PAS, the lower uterine segment widens to an hourglass-like appearance rather than the normal inverted-pear configuration.31,36 This major sign of PAS is more readily identifiable on coronal or sagittal planes and has a reasonable sensitivity (76.7%) and specificity (62.5%) for diagnosing PAS.10

Abnormal placental bulgeIn a meta-analysis, uterine bulge, placental bulge (placenta with lumpy contour), and placenta with rounded edges were grouped to gather and had a total sensitivity of 79.1 (60.3–90.4) and specificity of 90.2 (76.2–96.4) to predict PAS.37 Placental bulge is a major sign of PAS in MRI with two main types: (a) type I is a slight outward placental bulge into the underlying myometrial wall with intact and undistorted uterine contour; (b) type II is a focal placental bulge distorting the uterine contour (Fig. 6A–C).36

Placental heterogeneityA normal non-invasive placenta shows an intermediate signal in T2WI and is homogeneous in texture. However, the normal placenta might show some signal heterogenicity in up to 30% of the cases, particularly when gestation progresses beyond 32 weeks and placental maturation takes place.3 In the case of PAS, areas of calcification, hemorrhage, abnormal hypervascularity, focal pooling of blood, intraplacental dark fibrotic bands, and areas of placental infarction can all be the source of placental heterosignal change (Fig. 6A–C).4,36 Placental heterogenicity is subjective and mainly depends on the presence of abnormal intraplacental dark bands.6

Focal exophytic massesAs discussed among US features, this sign could be appreciated in MRI, similarly with a low sensitivity and high specificity for detecting placenta percreta; although the sensitivity is higher in MRI.20 Focal exophytic mass(es) is a major MRI sign of PAS and most commonly presents as an intermediate T2 signal mass bulging toward the bladder antroinferiorly (Fig. 7C and D). Sometimes placenta protrudes to the cervical internal os, a finding which has been stated as a major reliable sign of placenta accrete.32

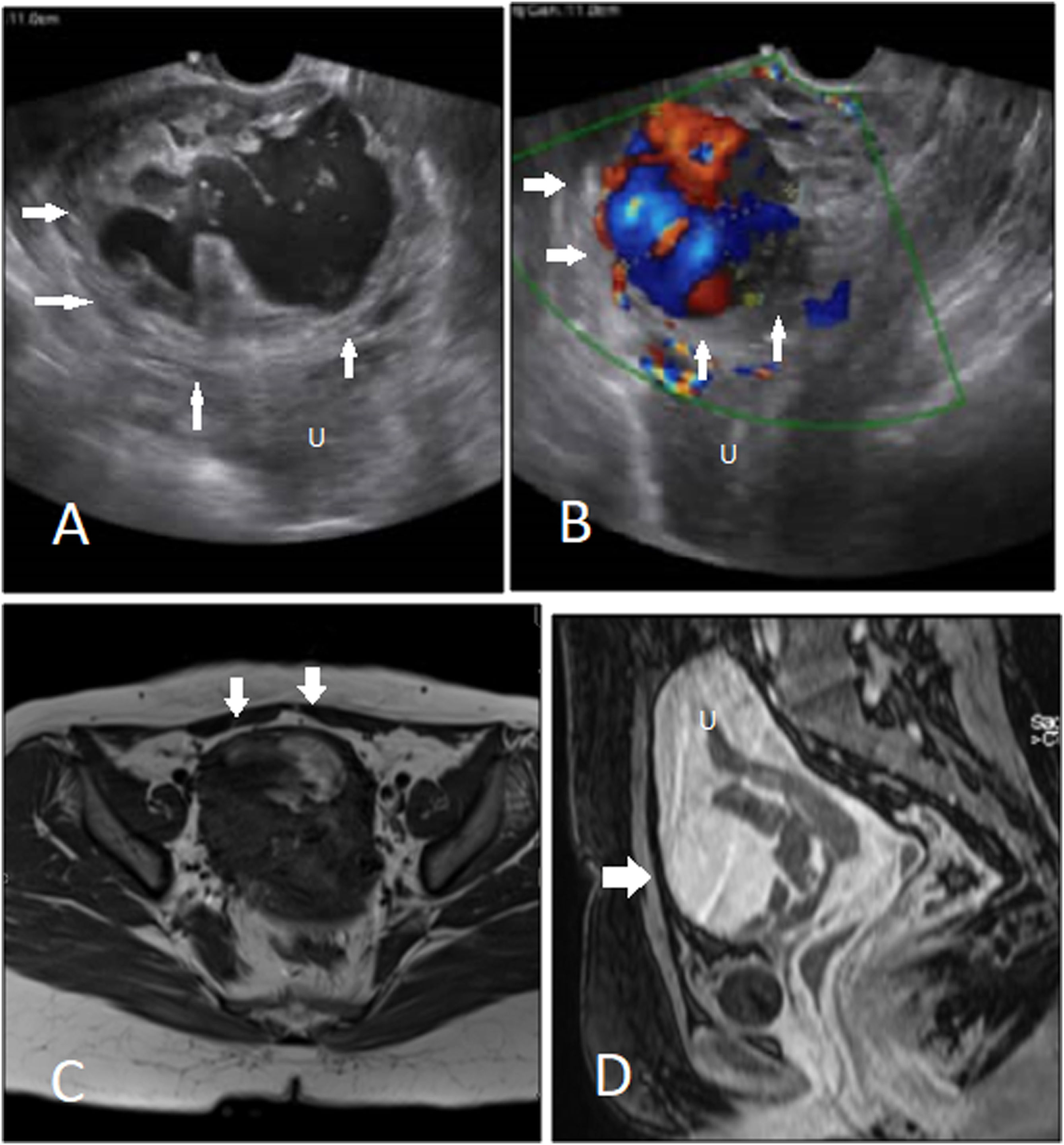

A complicated case of cesarean scar pregnancy with pseudoaneurysm. A, B. Transvaginal scan shows the scar pregnancy mass with a large pseudoaneurysm with to and fro pattern of flow detected in Doppler exam. C, D. Pre- and post-contrast T1-weighted imaging of the same case shows avid enhancement of the pseudoaneurysm. Uterus (U).

Visualizing placental tissue invading the bladder wall or protruding to the bladder lumen on MRI (Fig. 6A–C) indicates placenta percreta with specificity of 100%; notwithstanding, its sensitivity is very low.28

Visualizing multiple tortuous vessels bridging between the uterus and bladder, the so-called ‘bladder vessel sign’, has been reported as a precise predictor of PAS with a diagnostic accuracy of 96%.28

Dark T2 intraplacental bandsThese are irregular margin, randomly distributed, thick (maximum diameter of ≥6 mm) bands of low T2 signal intensity crossing the placenta perpendicularly (Fig. 6A–C).29,30 These bands are better visualized in SSFSE images (Fig. 6A and B). They originate from the maternal surface of the placenta and may cross the entire thickness of the placenta, reaching into the fetal surface. Dark placental band represent band-like areas of fibrin deposition.6,13,37 They are postulated to result from repetitive episodes of placental hemorrhage or infarcts. This feature has been shown variably sensitive and specific for PAS and is most valuable if other supporting MRI findings are present.19 If a dark intraplacental band is visualized with adjacent placental recess, it can be considered a major feature; however, dark band without adjacent placental recess is only a minor sign of PAS in MRI.32 The placental ‘recess sign’ is a wedge-shaped deformity resulting from the contraction of the placenta and overlying myometrium, accompanied by an intraplacental dark band.38 According to data from a meta-analysis, dark T2 band is the most sensitive MRI sign of PAS (82.6%–89.7%), with moderate specificity (49.5%–63.4%).10 Their main differential diagnosis are placental septa. Placental septa are thinner, and are more often seen in MR images taken at magnetic field of 3T.

Irregular placental–myometrial interfaceThis MRI feature is also known as loss of retroplacental hypointense line or uteroplacental interface, and is best appreciated on T2W images when the imaging plane is perpendicular to the placental–myometrial interface (Fig. 6C). Three parallel layers form the placental–myometrial interface: the myometrial rim of intermediate T2 signal, sandwiched between two low T2 signal layers (the inner decidua and the outer uterine serosa).31 High vascularity of the middle layer is highlighted on SSFP; thus, it provides the clearest image of the tri-laminar appearance of the placental–myometrial interface. Area(s) of thinning/interruption in this interface (especially the decidual layer) strongly anticipates PAS.4,31 This MRI feature is highly sensitive (97.4%) and poorly specific (36.4%), with even lower specificity at the site of a previous C/S or in advanced gestational age.5,32 MRI has the upper hand in the evaluation of the outer and middle layers (myometrium and uterine serosa); however, more superficial invasions are best visualized in US as it provides a better resolution than MRI.6

Myometrial thinningAs pregnancy progresses, the myometrium thinning normally occurs, sometimes to the extent that even at a technically adequate examination, myometrium may not be identified clearly. This MRI finding, as with US, is sensitive (63.6%, 67.9%, and 78.6%, for placenta accreta, increta, and percreta, respectively). Interpreting the abnormal myometrial thinning might be extremely difficult, particularly in third trimester, or at the site of previous cesarean delivery (Fig. 6C, F and G).13,37

Abnormal uteroplacental vascularityNormal pregnancy can exhibit a few flow voids within the placenta (usually located around umbilical cord insertion), in the uterine wall (commonly seen at the retroplacental region), or at the outer edge of the uterus (parauterine region).30 As gestational age advances, particularly after the mid-second trimester, these vessels show an increase in number and diameter to an expected extent, which may draw the attention of the examiner. In abnormal placentation, area(s) of marked and disproportionate uteroplacental vascular expansion and proliferation signal the foci of PAS.39 These vascular alterations more frequently reside within or around the placental bed (the decidua and adjacent underlying myometrium) and have been reported as the most accurate MRI feature of PAS, with specificity and positive predictive value of 100% (Fig. 5).28 Uteroplacental vascular pattern alteration in PAS might be identified in the placenta, placental bed, throughout uterine serosa (‘parametrial vessel’ sign, Fig. 6E), and in bladder wall (‘bladder vessel’ sign, Fig. 6D).

Abnormal intraplacental tortuous, ectatic (diameter >6 mm), proliferated, and bizarre vessels with nonuniform size and distribution, either in a diffuse manner, or focally as a tangle of vessels are indirect signs of PAS with the extent of abnormal hypervascularity being correlated with the depth of placental invasion.3 These dilated and disorganized vessels are correlated with irregular and bizarre shape placental lakes with turbulent internal flow, and are most commonly visualized next to dark T2 bands.30 Given that contrast agents are not recommended for antenatal use, finding abnormal vascularity in placenta mainly relies on comparing sequences with dark blood (SSFSE) and bright blood (SSFP) characteristics (Fig. 5D and E).30,31,36

At the area of the C/S scar, or in cases of severe placenta percreta, uteroplacental vascular pattern alteration could become obscured due to scar tissue or placental bulging.30

Imaging of PAS disorders in first trimesterFeatures of PAS disorders in ultrasonography may present as early as the first trimester; however, the diagnosis is made mainly in the second or third trimester.22,23,26,40 The first-trimester placenta accreta is relatively uncommon, and at the moment, widely accepted standardized sonographic criteria lack in the literature. Reported first-trimester features of PAS detectable on US exam are finding a gestational sac (GS) (Figs. 8A and B, and 9) or placental mass (Figs. 7 and 8D and E) that is embedded in the lower uterine segment (<5 cm from the external cervical os) or within the C/S scar, and the presence of multiple irregular lacunae within the placental bed.23,27

Two cases of cesarean scar pregnancy and placenta accreta are shown in MRI in the first trimester. A, B. T2-weighted image is showing cesarean scar pregnancy at 6 weeks. The gestational sac (GS) is implanted deep in the ‘niche’, and the overlying myometrium is thin. C. Early post-contrast dynamic T1-weighted image shows a significant hypervascularity around the sac. D, E. T2-weighted imaging of the placenta shows the scar pregnancy manifesting as a sizable heterogeneous mass. The mass resides in the ‘niche’, and it has protruded into the vesicouterine septum. F. Post-contrast T1-weighted image shows no hypervascularity within the hypo-/non-enhanced mass.

Moreover, US parameters discussed above for PAS in the second trimester, including placenta previa, irregularity in the developing placental–myometrial interface, intra/periplacental hypervascularity (Figs. 8C and 9B), and placental bulge (Fig. 8D and E) might be found as early as the first trimester.26,40

Identifying placenta previa in the first and second trimesters does not help to diagnose PAS, because it will often resolve as pregnancy progresses.41

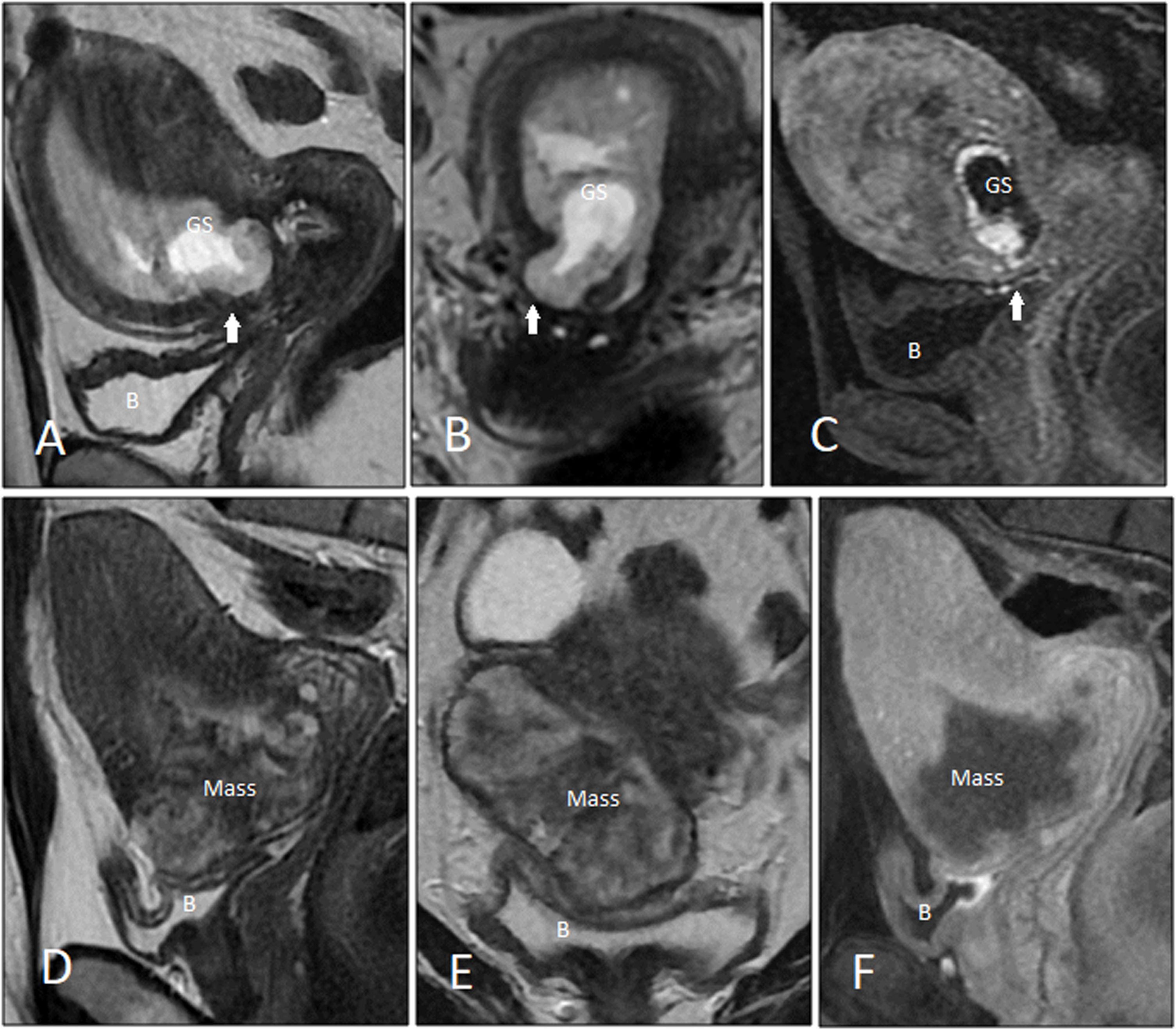

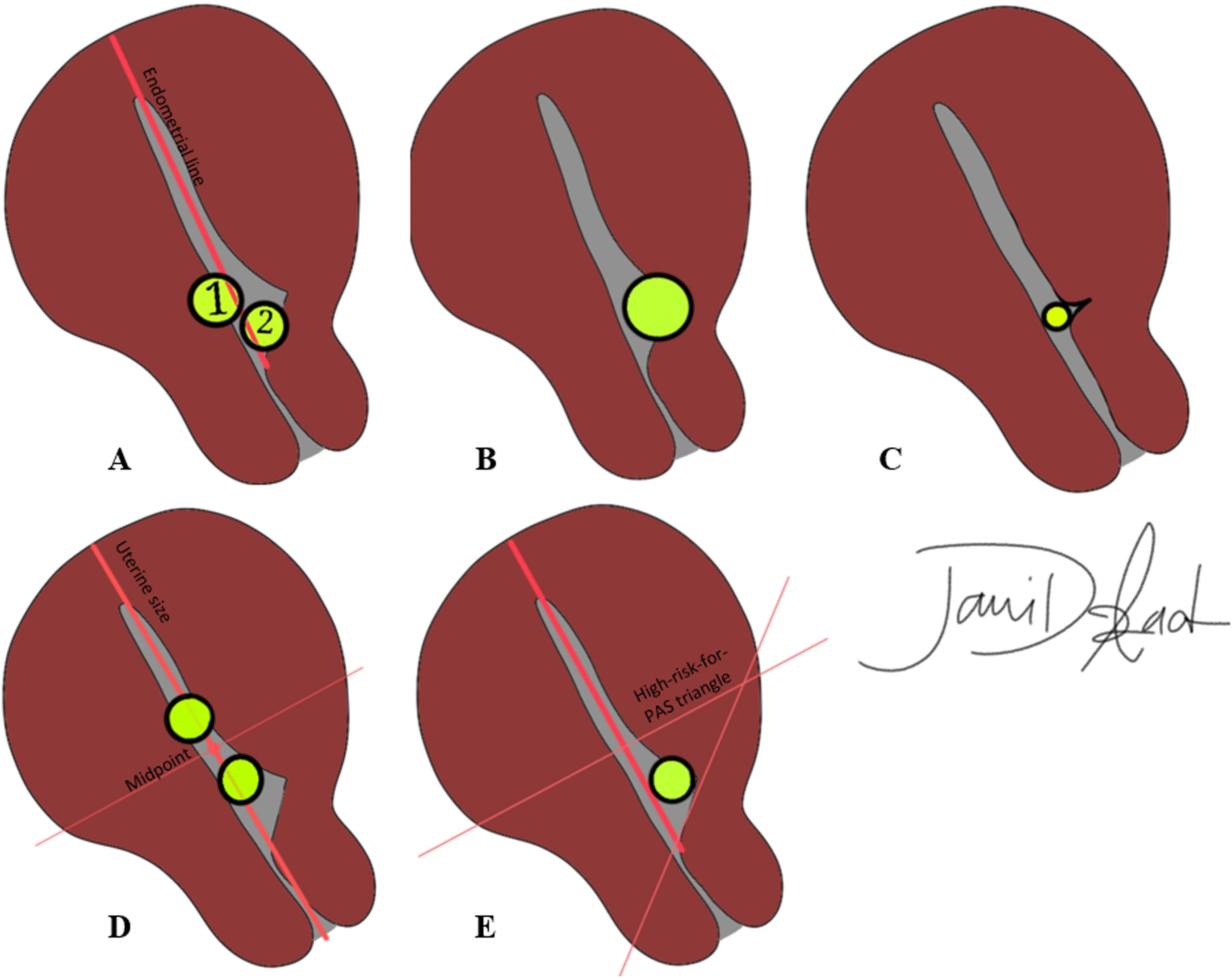

Cesarean scar pregnancyWhen the GS is implanted in the uterine window at bladder base at the level of cervical internal os, diagnosis of cesarian section delivery is made. There are a few imaging markers for CSP in the first trimester predicting a higher rate of following obstetric complications, mainly applicable to ultrasound: (a) the minimum myometrial thickness over the placenta: overlying myometrium thickness of <2 mm increases the chance of subsequent obstetric complications (Fig. 8A and B); conversely, myometrial thickness of >4 mm over the placenta is associated with a substantially better pregnancy outcome.42 (b) Cross over sign (Fig. 10A): the position of GS in relation to the endometrial line (a line drawn between internal cervical os, passing through the endometrium and crossing uterine fundus) is assessed in midsagittal view. If >2/3 of the superior–inferior diameter of the GS (traced perpendicular to the endometrial line) is above this line, pregnancy is at high risk for PAS.43 (c) Implantation in the niche vs. on the C/S scar (Fig. 10B and C): GSs implanted in the ‘niche’ (i.e., deficient or dehiscent C/S scar) demonstrated a poorer pregnancy outcome compared to those implanted ‘on the scar’ (fully or partially over a healed C/S scar).42Fig. 8 shows two cases of CSP with the product of conception implanted deep in the niche. (d) The location of GS in relation to the midpoint of the line drawn between external cervical os and uterine fundus (uterine size) (Fig. 10D): if GS resides above the line, the chances of CSP and related complications are significantly lower.44 In one study, authors combined three latter criteria and introduced a high-risk-for-PAS triangle (Fig. 10E).

A schematic presentation of ultrasound criteria for differing cesarean section pregnancy from intrauterine pregnancy and predicting the PAS severity in the third trimester. A. Cross over signs. If at least two-thirds of the superior–inferior diameter of the gestational sac resides above the endometrial line (sac 2), the risk of cesarean section pregnancy and subsequent poor pregnancy outcome is higher. Sac 1 more likely represents an intrauterine pregnancy. B, C. On the scar or in the niche. If the gestational sac is deep in the dehiscent cesarean scar (B), the risk of more severe placentation abnormality would be higher in the third trimester. If the sac is over a healed scar (C), normal intrauterine pregnancy is implied. D. Above or below the line. Gestational sacs above the uterine midpoint are more likely intrauterine pregnancies. If the gestational sac falls below the midpoint, the chance of cesarean section pregnancy and following severe PAS is higher. E. High-risk-for-PAS triangle. This triangle incorporates all criteria, and if the gestational sac falls within it, cesarean scar pregnancy is highly suggested, and patient will be more likely diagnosed with severe PAS in the third trimester.

Imaging evaluation is mandatory in all cases of PAS, as the clinical presentation of the invasive placenta will be quite subtle in some cases of abnormal placentation, and the timely diagnosis could be life-saving. Maternal serum biomarkers are not dependable for PAS diagnosis. Neither pathology nor imaging (US or MRI) findings of PAS in isolation are not very strong and confident to predict PAS. Both pathology and radiology may bring about false negative or positive results, and none of them are capable of predicting the depth of abnormal placentation confidently. A multidisciplinary approach considering clinical risk factors, imaging features, and pathological findings should make the diagnosis. With all these being said, diagnosing PAS is challenging and postoperative complications are quite common, even in facilities with a high level of expertise in managing PAS disorders.

Authors’ contributionsBM and JA provided direction and guidance throughout the preparation of this manuscript. SS, MG, ES and MA provided the images, searched the literature and contributed to data extraction from relevant published studies. BM, JA and MA drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and made significant revisions and approved the final version of the manuscript draft.

FundingThis research has not received specific aid from agencies from the public sector, commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We wanted to thank Masoumeh Gity and Maryam Rahmani, professors or radiology at Tehran University of Medical Sciences for their support and guidance throughout conducting this research work.