Suplement “Update and good practice in the contrast media uses”

More infoIodinated contrast is administered when carrying out computed tomography (CT) scans to define anatomical structures and detect pathologies. The contrast is administered according to different protocols which vary significantly and include vascular, visceral, multiphasic and split-bolus injection studies. Each protocol has its own indications and particularities to optimise the use of the contrast medium in each situation. There are numerous factors that influence the degree of contrast enhancement obtained, including the patient’s weight, cardiac output, study delay, the technical characteristics used for acquisition—mainly kilovoltage—, and variables related to the administration and dosage of the contrast medium, such as iodine delivery rate and load. This article will discuss how each of these variables affects the level of enhancement achieved and the parameters that can be modified in order to optimise the results of the different types of scans performed with iodinated contrast.

La administración de contraste yodado en una tomografía computarizada (TC) persigue delimitar estructuras anatómicas y detectar patología. Los protocolos de administración del contraste en las exploraciones de TC son muy variables e incluyen principalmente estudios vasculares, viscerales, multifásicos y con técnica de inyección bifásica, cada uno de ellos con unas indicaciones y particularidades que se deben conocer para optimizar el empleo del medio de contraste en cada situación. Existen numerosos factores que influyen en el grado de realce que se obtiene, entre los que se incluyen el peso del paciente, el gasto cardiaco, el retraso del estudio, las características técnicas empleadas para la adquisición, principalmente el kilovoltaje, y variables relacionadas con la administración y dosificación del medio de contraste, como el flujo y la carga de yodo. En este artículo se discutirá cómo afecta cada uno de ellos al realce obtenido y los parámetros que se pueden modificar para optimizar el resultado de los diferentes tipos de exploraciones realizadas con contraste.

The aim of administering iodinated contrast in a computed tomography (CT) scan is to delimit anatomical structures and detect disease thanks to the differences in attenuation achieved with the different distribution of contrast medium.1

The objectives of CT scans performed with intravenous contrast can be divided into two large groups: those that seek vascular enhancement, such as the different routinely performed CT angiograms; and those that predominantly seek visceral enhancement, usually in a portal phase, which is the goal in most studies that include the abdomen. In some situations it may be necessary to obtain both vascular and visceral information in the same scan, or to assess visceral enhancement at different stages, in these cases using different phases of or changes to the administration protocols for iodinated contrast media (ICM).

In this article, we review the different factors that influence enhancement in vascular and visceral CT scans and analyse the parameters that must be considered to optimise the results of a contrast-enhanced study. In addition, we make an analysis of dynamic or multiphase studies and the two-injection or split-bolus technique.

Enhancement optimisation in vascular CT studiesTechnological advances in CT equipment, injection pumps and image manipulation have enabled the development of different types of CT angiography as a first-line diagnostic technique in multiple settings. The wide variety of possible studies and equipment means that the radiologist needs to be aware of the options available for optimising enhancement. Furthermore, for reasons of quality, safety and cost, and even the risk of a shortage of ICM, the minimum amount of contrast should be used in each situation,2–4 just as with the use of radiation, especially in subjects with risk factors for nephrotoxicity. Improper use can lead to absurd situations, such as continuing to inject contrast when the acquisition has finished. We therefore need to strive for the personalisation of protocols, adapting them to the examination, the subject and the machine being used.3–7

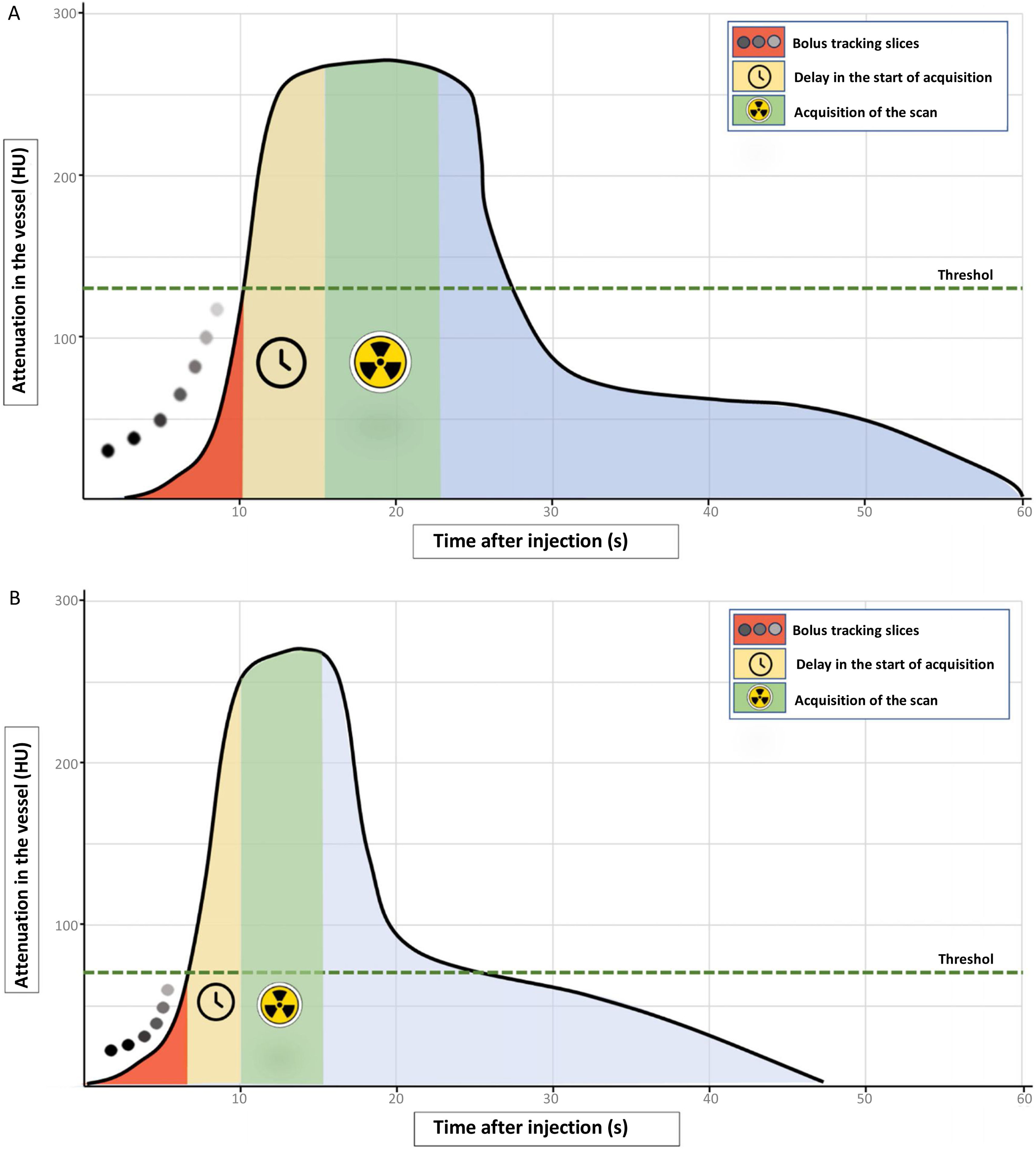

We discuss the possibilities of ICM optimisation by detailing the various points that can be modified to achieve a quality study. We begin by analysing the theoretical contrast curve in the vessel of interest, as shown in Fig. 1. A typical injection with a high flow of iodine results in a rapid rise in vessel attenuation, which is followed by an equally rapid decrease in the case of a short-duration injection.1 The primary objective of an CT angiogram is that the acquisition coincides with the moment of greatest attenuation in the desired vessel; to do this, we must make sure that the study begins as close to the peak as possible, and that level of vascular attenuation is maintained throughout the study and for the duration of the acquisition. The calculation of the ICM dose would be the result of multiplying the injection rate by the duration of the scan, adding an amount of “safety” contrast, which will vary according to the direction of flow in the area studied, the extent and duration of the scan, and the delay after reaching the threshold we have established until the point where start of our study.

Theoretical representation of the attenuation curve in a vessel during a standard short high-speed contrast injection in CT angiogram (A), and adjusting the contrast dose (B). A) In a typical injection, the first phase corresponds to the bolus tracking slices in the determined area of interest (red shading). When the preset threshold is reached (dashed green line) the delay time countdown for the start of acquisition begins (yellow shading). After this time, the acquisition of the scan begins (green shading), which must coincide with the values of greatest attenuation in the vessel of interest. B) To optimise the use of the contrast bolus, the threshold for starting the study can be reduced or, optionally, it can be started manually when the examiner visually identifies the arrival of the contrast at the region of interest. The next step is to reduce the delay time as much as possible between reaching the threshold or starting the scan by the operator and beginning the acquisition (yellow shading). Finally, as explained in the text, there are sometimes technical possibilities for reducing the acquisition time (green shading). As can be seen, the difference between the two curves is the time that the plateau of the contrast peak lasts, being wider in the standard injection, while in the dose adjustment, the same peak is reached, but in less time, making it necessary to adjust the start of the study, its duration, or both.

In other words, to define an intravenous ICM administration protocol in a vascular study and to make optimal use of it, a variety of aspects need to be taken into account, and we discuss these below:

Study objectiveThere is no definition of when a CT angiogram is appropriate and, in fact, not all scans require the same level of attenuation. The dose must therefore be adapted to these needs and the subject’s characteristics. Studies such as CT angiography of the pulmonary arteries or the aorta would require a minimum attenuation level of around 200 HU.8,9 In contrast, a coronary artery CT angiogram should reach values of 325–400 HU.10,11

Know our scannerThe wide range of CT scanners available and their technical capabilities mean that the possibilities of reducing contrast dose and optimising the vascular images obtained are largely determined by the characteristics of the equipment we use. The radiologist therefore needs to understand its technological capabilities and adapt the contrast injection protocols accordingly. The scanning time can vary significantly, depending on the scanner. Other aspects which depend on the machine and may be of use for reducing the contrast dose are the range of kilovoltage values that can be selected, the delay from when the threshold is reached until the study begins, different image reconstruction techniques, which enable better quality at a lower dose,12–14 and the possibility of acquiring different varieties of spectral images.15

Factors that influence enhancementAlthough there are many such factors, the main ones that influence vascular enhancement are the subject’s weight, cardiac output, the study’s technical characteristics, and the iodine flow rate administered.1,2,16

Weight is a determinant of enhancement in CT studies, although its impact is more important in visceral assessment. In vascular examinations, the influence of small weight variations is relatively minor, so it is common to use standard injection rates. However, the injection rate would have to be adapted to the patient's weight when it is at extreme levels, as there is an inverse relationship between weight and attenuation.17–20 Software is available that takes weight into account to adjust the iodine administration flow rate. In the absence of such software, how to adapt the injection rate to the patient’s weight in routine practice will depend on many of the factors we are discussing in this section. For example, in the experience of certain authors of this article, and according to what some studies have found,17 for a CT angiogram of pulmonary arteries, the use of 4 ml/s with a concentration of 350 mg of iodine/ml provides valid attenuations in the vast majority of subjects weighing 50 to 80 kg. However, as we will see later, lighter subjects benefit from reducing the kilovoltage and injection rate. Some studies find this variable to have less influence on attenuation in heavier patients,20 which in practice means examinations with this injection rate is acceptable for almost all subjects up to around 90 kg.17 Above that weight it may be advisable to increase the rate to 4.5–5 ml/s.

Cardiac output significantly determines arterial enhancement and is the physiological factor that most influences this in a given patient.1,21 However, cardiac output is not usually known before the scan and can only be monitored if we perform the examinations using the bolus tracking technique. A decreased cardiac output determines a later, but also higher, enhancement peak,1,3,22 and increased transit time of the contrast from the pulmonary artery to the aorta,2 which needs to be taken into account in examinations that require enhancement of both vessels. In such cases, if the study is performed using the bolus tracking technique, the aorta should be taken as a reference and sufficient contrast should be administered so that the bolus covers the pulmonary arterial tree at the time of acquisition. If this factor is not taken into account, it is likely that the study will only be suitable for one part of the circulation (pulmonary or systemic arterial), which means the examination must be repeated to assess the sector that was not sufficiently contrasted.

Reducing the kilovoltage acquired in the study is a very useful tool for reducing contrast needs. By using low kilovoltage (80–100 kV) or, in scanners with spectral analysis capabilities, low-energy monoenergetic images (40 keV), we obtain greater vascular attenuation, thus reducing the need for more ICM.6,9,22,23 Although these images may have greater noise, the quality has been reported to be acceptable,22 even in subjects who are not necessarily thin,23 allowing what is called a “double low dose”, with good quality studies in which both the radiation and contrast dose are low.24,25 Each type of study, subject and equipment can support different combinations of kilovoltage reduction and, consequently, injection rates. For example, in our experience, using iterative reconstruction methods, diagnostic quality CT angiography studies can be performed with 80 kV and injection rates of 2.5–3 ml/s in most subjects.25,26

Lastly, the individual factor that most influences vascular enhancement is the iodine delivery rate,24–28 which is expressed in grams of iodine per second, and is determined by the ICM concentration and the injection speed, according to the formula:

A higher maximum peak is achieved and reached earlier at high flow rates compared to lower delivery rates.7 The choice of iodine delivery rate in a scan is mainly determined by its objective, being highest in the study of coronary arteries (1.6–2.0 g of iodine/ml) and somewhat lower for the assessment of the aorta or pulmonary arteries (1.4–1.6 g of iodine/ml). These values can be reduced when using a lower kilovoltage.6,7,26,28

In cases where the quality of venous access limits the injection rate, a contrast medium with a higher concentration of iodine means the injection rate can be lower, keeping the iodine delivery constant.7,29,30 In these situations, one option is to reduce the kilovoltage, which, as we have seen before, allows us to obtain greater attenuation with lower injection rates. Furthermore, the use of a bolus of saline solution after the contrast allows the contrast to be pushed into the bloodstream and compacted, preventing it from remaining stagnant in the venous territory.31

Factors that can reduce the scanning time or the start of a scanSince the acquisition time, in conjunction with the injection rate, is a determinant of the ICM dose we need to administer, reducing the duration and adjusting other factors in the protocol can serve as tools to help reduce the dose. Possible adjustments, some of which are shown in Fig. 1B, include:

- a

Reducing the acquisition time, which on the one hand can be achieved by adjusting the scan as far as possible to the area of interest, and on the other by adjusting parameters so that there is broader coverage in a given time (increasing the speed of the table, with a higher tube rotation speed or adjusting the collimation).

- b

Setting the acquisition to the start of the attenuation peak. Using the bolus tracking technique, this adjustment can be achieved in several ways: lowering the threshold at which the study is started so that it is reached sooner, even starting it manually when the arrival of the bolus is detected visually; reducing to a minimum the time from reaching the threshold to the start of the study; or placing the area of interest in a location closer to the arrival of the contrast (for example, in the superior vena cava instead of in the pulmonary artery when performing a CT pulmonary angiogram). The direction and velocity of blood flow, and therefore the contrast, must be taken into account, as in relatively long studies, acquisitions in the direction of blood flow may be at an advantage (Fig. 2). However, with very fast equipment, the possibility of the acquisition happening before the contrast arrives needs to be considered (for example, in a lower limb CT angiogram), and this must be avoided by increasing the amount of contrast and delaying the start of the scan, or by changing the protocol to guarantee contrast at the end of the scan.32

Figure 2.CT angiogram of chest, abdomen and pelvis for planning a transfemoral aortic valve replacement. In a patient weighing 82 kg and 169 cm in height, the acquisition of the study lasted 10.1 s. 40 ml of iodinated contrast was administered at an injection rate of 4 ml/s, followed by 40 ml of normal saline at the same rate. The region of interest was placed in the ascending aorta at a threshold of 100 HU, but the study was started manually when the operator visualised the arrival of the contrast at that point. The scan start delay was 5.6 s (the minimum set by the machine). As can be seen, attenuation was similar, above 300 HU, in ascending aorta, descending aorta and femoral arteries. Note that at the time of acquisition the contrast bolus had already completely passed through the right ventricle (asterisk in B), which does not show any enhancement. The use of this dose is possible because the start of the scan was adjusted to the arrival of the contrast in the ascending aorta and because it was acquired with the direction of flow in the aorta.

Fig. 1B and Fig. 3 summarise some of the steps that can be followed to adapt the contrast protocol in a vascular study. Routinely used contrast administration protocols should take into account the standard patient and parameters which enable reproducibility by all personnel with good results. However, in special circumstances, when it is necessary to reduce the contrast dose, for example, in subjects with significant renal function impairment, variations from these protocols can be made to reduce the amount of contrast administered. An example of how the protocol can be adapted to a specific scanner is shown in Table 1. In these same circumstances, an alternative, if the subject’s weight allows, would be to reduce the kilovoltage and, at the same time, the injection rate and the volume administered, as discussed above.

Example of adaptation of a standard CT pulmonary angiogram protocol to one for reducing contrast dose in a 16 detector-row scanner.

| Parameter | Standard protocol | Protocol with dose reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Start of bolus tracking test slices | 8 s | 4 s |

| Threshold for the start of acquisition | 120 HU | 100 HU (manual start by the operator when the arrival of the bolus is identified) |

| Delay in the start of acquisition after the threshold | 6 s | 4 s |

| Collimation | 16 × 0.6 mm | 16 × 1.2 mm |

| Approximate duration of the study | 12 s | 6 s |

| Minimum reconstruction thicknessa | 1 mm | 1.5 mm |

| Contrast medium injection rate | 4 ml/s | 4 ml/s |

| Amount of contrast medium | 60 ml | 30–35 ml |

| Amount of saline solutionb | 30 ml | 45 ml |

When a CT scan is performed in the portal phase, which in routine practice means the vast majority of scans that include the abdomen, the quality of the study can be defined by the enhancement achieved in the liver parenchyma with intravenous administration of ICM. In the literature, an increase in liver attenuation of at least 50 UH over its baseline value is classically taken as a reference33,34 or reaching a minimum attenuation of 100–110 UH as an absolute value (120 UH in the spleen if there is hepatic steatosis).35,36

To achieve these attenuation values, there must be an adequate dose of ICM administered, which in studies of viscera can be defined with the concept of iodine load, which relates the grams of iodine administered to a unit corresponding to the subject’s body size, in terms of weight or body surface area.33,37 The amount of iodine administered is therefore related to the subject’s own characteristics, which enables a personalised adjustment of the dose.

Therefore, to calculate the iodine load in a given subject, the amount of iodine administered considers the relation, for example, to their weight, according to the formula:

This adjustment will be more useful in scans of viscera, as liver enhancement depends mainly on portal venous supply.38

Unlike protocols that use a fixed volume of ICM, the use of iodine load as a reference helps obtain studies with more homogeneous visceral attenuation values. In the case of abdominal CT protocols where, for example, 100 ml of ICM are prescribed for all subjects, we may find some limitations: on the one hand, the concentration of iodine in that volume is not considered, so the dose can be very variable (for example, 100 ml with a concentration of 300 mg/ml provides 30 g of iodine, while if the concentration were 400 mg/ml, it would be 40 g of iodine, that is, 33% more); on the other hand, a fixed volume not adapted to the subject's characteristics can cause highly variable visceral enhancements, which can be inadequate in many cases, due to excess or deficiency (Fig. 4).

To try to optimise the enhancement in viscera scans, we have to understand the most important variables that determine the enhancement and how they influence it. These points are summarised in Table 2 and discussed below.

Summary of parameters that influence visceral enhancement.

Greater volume or greater concentration will logically mean a larger dose of iodine, which will produce a proportional increase in visceral enhancement1 (Fig. 5A and B).

Simulated curves of liver enhancement over time. A) After injecting three different volumes of contrast medium with the same concentration into the same patient. B) After injection of the same volume of contrast with three different concentrations. C) In subjects of different weights and the same height, keeping all parameters related to contrast (flow rate, volume and concentration) fixed.

Greater weight is generally related to greater blood volume, so the contrast is more diluted, especially if the opacification is going to depend on venous return. Therefore, with the same dose of ICM, heavier weight leads to less visceral enhancement (1) (Fig. 5C).

However, although weight is the most commonly used variable for adjusting the ICM dose, it has the limitation that it may not adequately represent the body volume in which the contrast will be distributed. In obese subjects, as fat has little vascularisation, it will also have little influence on blood volume and venous return (1). Therefore, in subject sin whom a large part of their weight is made up of fatty tissue, adapting the ICM dose to kilograms would overestimate the need for contrast.39

As can be seen in Fig. 5C, in subjects weighing from 50 to 100 kg, a proportionality between weight and enhancement does seem to be maintained. In these cases, the iodine loads recommended by the literature can be used to achieve the liver enhancement objectives discussed above, with values between 0.52 and 0.60 g/kg.33,34,37 If we take an iodine load, for example 0.60 g/kg, as a reference, by adjusting the formula, we can calculate the necessary volume to be administered if we know the other parameters: contrast concentration and the subject’s weight.

However, above 100 kg, where there is a greater likelihood of the heavier weight being due to obesity, meaning a higher proportion of bodily fat tissue, the influence of weight on enhancement is considerably less. In this case, it would be necessary to consider whether the volume of distribution in this group of subjects requires a lower dose of iodine than would correspond to their weight, as these high weights will be due to obesity in most of the population.

In obese subjects, therefore, the use of anthropometric variables other than weight has been proposed, such as lean body mass or body surface area, which might help better adjust the iodine dose, by maintaining a greater correlation with the expected enhancement.37,39–44

Other variablesOther variables that influence visceral enhancement, such as injection flow rate, cardiac output and kilovoltage, have already been discussed in the section on vascular CT studies. However, there are some differences in the degree of influence between the two types of studies which should be discussed.

Regarding the injection flow rate, despite not being such an important factor in viscera studies as the iodine load, it is essential to remember that very low flow rates can lead to inadequate enhancement with appropriate iodine loads.

With flow rates of 3 to 5 ml/s, maximum liver enhancement is achieved during the portal phase, around 70 s. However, with very low flow rates, the peak enhancement may be very late, as the injection will last longer, and maximum liver attenuation will only be achieved with the entire dose of iodine distributed throughout the body. Furthermore, this delay will also lead to greater dilution of the contrast, which means that the same peak enhancement that occurs in faster injections will not be achieved (Fig. 6).1

Similarly, with very high volumes of ICM, although the liver enhancement peak will be greater, the point at which the peak will be reached will be later than in a normal portal phase, when all the contrast has been distributed and returned by the venous circulation (Fig. 5A).1

From Figs. 5 and 6 it can be extrapolated that at least 25–30 s are needed from the end of the injection for the entire administered dose of iodine to achieve maximum attenuation of the liver parenchyma. Therefore, for an image acquisition theoretically in the portal phase, for example at 70 s, injections lasting more than 40 s (either due to low flow rate or very high volumes) will result in a suboptimal attenuation study. It may be the case that contrast is still being injected when the acquisition starts, or even after it has finished. To avoid these circumstances, where part of the administered contrast will not be useful in opacification of the viscera, we need to try to adapt the speed of administration of the ICM so that the duration of the injection does not exceed 40 s; if this is not possible, a suitable adjustment to the delay in acquisition is necessary.

As cardiac output will influence the speed of iodine distribution, a decrease in output will lead to later enhancements (1). This is usually a factor which cannot be controlled before performing the study and it leads to inadequate enhancement in a small number of subjects. To avoid it, as seen in Table 3, instead of a fixed time delay, an alternative is to use automatic bolus tracking in viscera scans, which can partly offset the delay in bolus arrival caused by low cardiac output.

Characteristics and uses of different phases in contrast-enhanced CT.

| Phases | Technical characteristics | Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Without contrast | Before administration of contrast | Differentiate tissues such as calcium, fat or blood |

| Early arterial | 15–20 s after the start of contrast injection or immediately after ABT | Anatomical arterial mapping, search for active bleeding |

| Late arterial | 35–40 s after start of contrast injection or 15 s after ABT | Detection of hepatic hypervascular lesions |

| Portal | 70–75 s after start of contrast injection or 50–55 s after ABT | Detection of hepatic hypovascular lesions |

| Pancreatographic | 20 s after ABT | Detection of pancreatic lesions |

| Enterographic | 20–25 s after ABT | Small bowel assessment |

| Nephrographic | 90–100 s after start of contrast injection or 80 s after ABT | Detection of renal parenchyma lesions |

| Late hepatic or equilibrium | 3 to 5 min after the start of contrast injection | Detection of fibrous tumours such as cholangiocarcinoma that retain contrast in this phase or to assess washout in malignant hypervascular lesions (hepatocellular carcinoma, metastasis) |

| Excretory or urographic | 7–12 min after the start of contrast injection | Detection of urothelial tumours and extravasation in traumatic lesions of the excretory tract |

ABT: automatic bolus tracking.

With regard to the kilovoltage, reducing it in examinations of viscera leads to greater limitations than in vascular CT, as the increased noise can often limit the diagnostic capacity, despite other measures which may offset the noise, such as increasing the milliamperage or iterative reconstruction.45,46

Different studies suggest minimum iodine loads for achieving adequate liver enhancement for kV below 120 kV, of 0.4 g/kg and 0.3 g/kg using 100 and 80 kV respectively.35,47,48 Spectral technology also opens up the possibility of using iodine loads much lower than normal, with liver enhancement values suitable for diagnosis.49

Other factorsOther factors that can help with better distribution of contrast in CT of viscera are the administration of 30–40 ml of saline solution after the contrast to better ensure the entire administered dose is being used and, in high-concentration contrasts, the use of pumps that increase their temperature to body temperature can facilitate injection at higher flow rates by reducing their viscosity.35

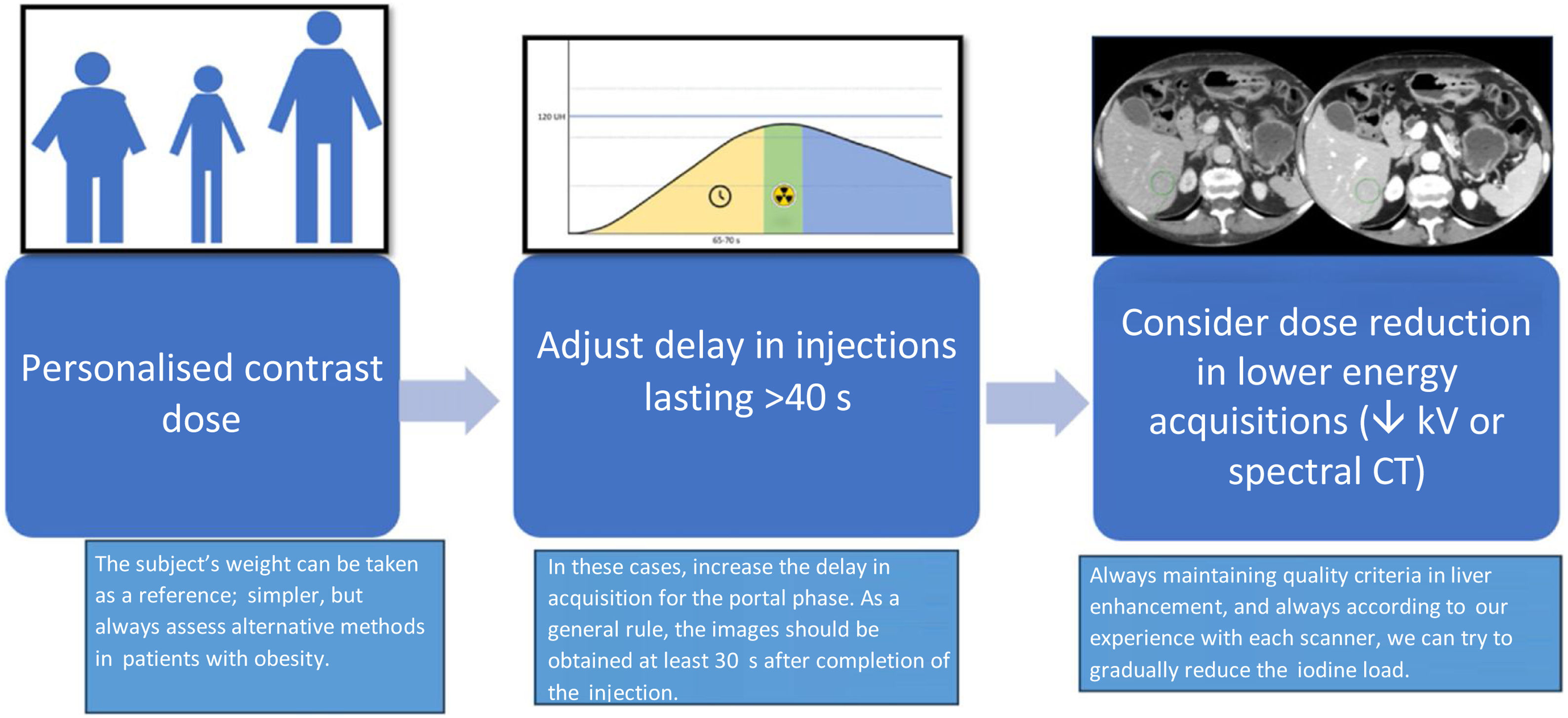

Once the most important variables that affect visceral enhancement are understood, we can consider how to adjust the dose of intravenous contrast as much as possible in these examinations. The procedure for adjusting contrast dose in CT of viscera can be summarised in the steps set out in Fig. 7.

Dynamic or multiphase scansThe aim of multiphase CT scans is to study the behaviour of organs and lesions in different phases.50 Contrast media are markers of extracellular fluid, as once injected they are rapidly distributed between the extracellular vascular and interstitial spaces.38 Taking advantage of this situation, there are different protocols which combine the two phases according to the indication for the scan. A multiphase study may consist of a baseline or non-contrast series (which is optional), an arterial phase, a visceral or parenchymal phase and, occasionally, another more delayed phase (Fig. 8). As stated previously, the arterial phase will be determined by the iodine delivery rate, while the visceral phase will depend mainly on the iodine load.38 In this type of scan the iodine injection flow rate should therefore be high, similar to a vascular study, while the total iodine dose should be adjusted to the visceral phase and, therefore, to the body volume.

The phases most widely used in clinical practice, their characteristics and uses are shown in Table 3.50–52

As in other scan types, the effect of decreased cardiac output must be taken into account in multiphase studies. Decreased cardiac output in the arterial phase will produce later, but more intense and prolonged enhancement, while in the visceral phase, it will cause much later enhancement.1 As a consequence, there may not be good enhancement in the visceral phase, as there is set time between the arterial and visceral phases. Because this situation is often unpredictable, a new acquisition may be necessary to obtain a scan at the time of maximum visceral enhancement. If the person responsible for carrying out the scan detects such a situation, it may be possible to immediately repeat the visceral phase to take advantage of the contrast administered.

Split-bolus injection techniqueThe most commonly used technique in CT scans is single-bolus. However, double injection, biphasic injection, discontinuous injection or split-bolus is a technique for administering iodinated contrast which enables simultaneous study of different structures that enhance with different delay times, such as arteries and veins or the excretory system and renal parenchyma. This allows a single helical acquisition to be performed instead of several multiphase acquisitions. The split-bolus protocol has been shown to significantly reduce the ionising radiation dose received and the number of images in the studies, compared to multiphase scans.53 This may require an increase in the amount of contrast medium administered.

Technically, it is achieved by dividing the contrast injection into two or more boluses separated by an injection of saline solution and a pause, with an initial bolus to provide the enhancement of the structure that would have the longest delay and a second bolus for the enhancement of the structures with the shortest delay. For example, in the case of a CT of the abdomen and pelvis, the initial bolus provides the enhancement of the viscera and the second bolus, at a higher flow rate, is responsible for the vascular enhancement54 (Fig. 9 and 10).

Arterial (red) and hepatic (green) enhancement curves after administration of iodinated contrast with a single-bolus (A) and split-bolus (B) protocol. The grey rectangle represents the time of image acquisition. The upper part of the figure shows the contrast and normal saline injection boluses. In the split-bolus contrast injection (B), the second bolus is responsible for the greatest arterial enhancement.

CT of the abdomen at the liver and kidneys after administration of iodinated contrast with a single-bolus (A) and split-bolus (B) protocol. In both studies, the same enhancement of the suprahepatic veins (arrows) is observed, but the enhancement of the abdominal aorta (arrowheads) is greater in the split-bolus injection.

One way to perform the calculation on a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis using the split-bolus technique would be as follows:

- •

The delay for obtaining a scan in visceral phase is 70 s and for enhancing the aorta, would be 20 s.

- •

The start of the injection would be second “0” and the scan would have to start at 70 s.

- •

The first bolus could be 80 ml with a flow rate of 2.5 ml/s, which would last 32 s.

- •

Then 30 ml of saline solution is then injected at 3 ml/s, which would last 10 s.

- •

The second bolus for arterial enhancement should start 20 s prior to starting the acquisition, then there should be a pause of 8 s between the end of the saline injection and the start of the second bolus (70 – 32 – 10 = 28 s, overall delay minus duration of first ICM bolus and saline, then 28 s remaining at the start of the study; 28 – 20 = 8, the pause is 8 s because the last 20 s are used to inject the second boluses, of contrast and saline).

- •

The volume of the second bolus could be 35 ml, which at a flow rate of 3.8 ml/s would last 9 s.

- •

Finally, it would be washed out with 40 ml of saline at a flow rate of 4 ml/s.

There are many applications of split-bolus contrast injection, but it is particularly used in head and neck studies, stable subjects with multiple trauma, and CT urography.54–56Table 4 shows various proposals for split-bolus contrast injection.

Proposed split-bolus contrast injection protocols.

| CT of chest-abdomen-pelvis |

|---|

| 1. Total delay: 70 s or ABT + 50–55 s |

| 2. First bolus: 80 ml, 2.5 ml/s, duration 32 s |

| 3. Normal saline: 30 ml, 3 ml/s, duration 10 s |

| 4. Pause: 8 s |

| 5. Second bolus: 35 ml, 3.8 ml/s, duration 9 sec. |

| 6. Normal saline: 40 ml, 4 ml/s |

| CT of head and neck |

| 1. Total delay: 80 s or ABT + 60–65 s |

| 2. First bolus: 80 ml, 2.5 ml/s, duration 32 s |

| 3. Normal saline: 30 ml, 3 ml/s, duration 10 s |

| 4. Pause: 13 s |

| 5. Second bolus: 30 ml, 3 ml/s, duration 10 s |

| 6. Normal saline: 30 ml, 3 ml/s |

| CT urogram |

| 1. First bolus: 1/3 of the total ICM, 2.5 ml/s |

| 2. Normal saline: 40 ml, 2.5 ml/s |

| 3. Pause: 8 min |

| 4. Second bolus 2/3 of the total ICM, 2.5 ml/s |

| 5. Normal saline: 40 ml, 2.5 ml/s |

ABT: automatic bolus tracking.

Contrast administration protocols in CT scans are highly variable and mainly include vascular, visceral, multiphase and split-bolus injection technique studies, each with indications and particularities that we have to be fully aware of, in order to optimise the use of contrast in each situation. As radiologists, our knowledge of the scanner’s technical parameters, the factors that determine enhancement, and the distribution of the contrast medium in the body will enable us to adapt the administration protocols to each type of study and thereby obtain the best results.

FundingThis study has not received any type of funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statement- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 2

Study conception: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Gemma Fernández Suárez and Juan Calvo Blanco.

- 3

Study design: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Gemma Fernández Suárez and Juan Calvo Blanco.

- 4

Data collection: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Gemma Fernández Suárez and Juan Calvo Blanco.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Gemma Fernández Suárez and Juan Calvo Blanco.

- 6

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7

Literature search: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Gemma Fernández Suárez and Juan Calvo Blanco.

- 8

Drafting of the article: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Gemma Fernández Suárez and Juan Calvo Blanco.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Gemma Fernández Suárez and Juan Calvo

- 10

Approval of the final version: Juan José Arenas-Jiménez, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Gemma Fernández Suárez and Juan Calvo Blanco.