To know the anatomy of the pulmonary veins (PVs) by multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) prior to ablation.

Materials and methodsMDCT was performed in 89 patients with AF, analyzing the number of PVs, accessory variants and veins, diameter and ostial shape, distance to the first bifurcation and thrombus in the left atrial appendage.

ResultsThe most frequent venous pattern was 4 PVs (two right and two left) in 49 patients (55.1%). The superior veins had a statistically significant greater mean ostial diameter than the inferior veins (Right Superior Pulmonary Vein (RSPV) > Right Inferior Pulmonary Vein (RIPV); p=0.001 and Left Superior Pulmonary Vein (LSPV) > Left Inferior Pulmonary Vein (LIPV); p<0.001). The right pulmonary veins ostial diameters were significantly larger than the left pulmonary veins ostial diameters (RSPV>LSPV; p<0.001 and RIPV>LIPV; p<0.001). The most circular ostium was presented by the VPID (ratio: 0.885) compared to the LIPV (p<00.1) and LSPV (p<0.001). The superior veins had a statistically significant greater mean distance to first bifurcation than the inferior veins (RSPV>RIPV; p=0.008 and LSPV>LIPV; p=0.038). Mean distance to first bifurcation has been greater in left PVs respect to the right PVs (LSPV>RSPV; p<0.001and LIPV>RIPV; p<0.001). Other findings found in AI: diverticula (30), accessory auricular appendages (5), septal aneurysms (8), septal bags (6) and 1 thrombus in the left atrial appendage.

ConclusionMDCT prior to ablation demonstrates the anatomy of the left atrium (LA) and pulmonary veins with significant differences between the diameters and morphology of the venous ostia.

Conocer la anatomía de las venas pulmonares (VVPP) mediante tomografía computarizada multidetector (TCMD) en pacientes con fibrilación auricular (FA) antes de la ablación.

Material y métodosRealizamos TCMD a 89 pacientes con FA analizando número, variantes y venas accesorias pulmonares, diámetro y forma o, distancia a la primera bifurcación y trombo en la orejuela izquierda.

ResultadosEl patrón venoso pulmonar más frecuente fue 4 VVPP (dos derechas y dos izquierdas) en 49 pacientes (55.1 %).

Las VVPP superiores presentaron mayor diámetro ostial que las inferiores [vena pulmonar superior derecha (VPSD) > vena pulmonar inferior derecha (VPID); p=0,001 y vena pulmonar superior izquierda (VPSI) > vena pulmonar inferior izquierda (VPII); p<0,001]. El diámetro ostial de las VVPP derechas era mayor que el de las izquierdas (VPSD > VPSI; p<0,001 y VPID > VPII; p<0,001). El ostium más circular lo presentó la VPID (ratio: 0,885) respecto a la VPII (p<0,001) y a la VPSI (p<0,001). La distancia a la primera bifurcación ha sido mayor en las venas superiores (VPSD > VPID; p=0,008 y VPSI > VPII; p=0,038). La distancia a la primera bifurcación fue mayor en las VVPP izquierdas (VPSI > VPSD; p<0,001 y VPII > VPID; p<0,001). Otros hallazgos fueron: divertículos (30), apéndices auriculares accesorios (5), aneurismas septales (8), bolsas septales (6) y 1 trombo en la orejuela izquierda.

ConclusiónLa TCMD antes de la ablación demuestra la anatomía de la aurícula izquierda (AI) y de las VVPP con diferencias significativas entre los diámetros y morfología de los ostium venosos.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in the general population.1 The finding published in 1998 that episodes of AF begin, in more than 90 % of cases, in the final segment of the pulmonary veins (PV), close to their point of entry into the left atrium (LA),2 paved the way to the development and expansion of a procedure to treat AF with intravascular catheter ablation.

According to both the American and European Cardiology Societies,3,4 PV ablation is indicated in patients with symptomatic AF (paroxysmal or persistent) that is resistant to antiarrhythmic treatment.

Percutaneous ablation consists of the complete electrical disconnection of the PVs from the atrial tissue. A non-invasive imaging technique that can accurately show the anatomy of the LA, the number of veins and their ostia,5 and exclude thrombi in the left atrial appendage, is essential for successful ablation, since thrombi are an absolute contraindication for the procedure.6

One such technique is multidetector computed tomography (MDCT). MDCT should be performed 24h before ablation in order to avoid the changes in LA anatomy and volume caused by fluctuations in the heart rate of these patients.7

In this study, we used electrocardiograph (ECG)-synchronised MDCT prior to ablation to map the anatomy of the pulmonary veins and LA in patients with AF, and performed a statistical analysis of the anatomical variability of venous ostia.

Material and methodsSubjectsFrom February 2015 to February 2018, we performed MDCT on 89 patients with symptomatic AF (paroxysmal in 76 cases and persistent in 13) resistant to medical treatment who were scheduled for treatment with pulmonary ablation. The cohort included 59 (66 %) men and 30 (34 %) women. The age range was 36–76 years, mean 55.61 years (± SD: 10.152), and 38–76 years, mean 59.43 years (± SD: 8.508) in men and women, respectively.

Multidetector computed tomographyAll patients underwent retrospective ECG-synchronised MDCT (Toshiba, Aquilion 64 Otawara, Japan), with no ECG-based radiation dose modulation, since, due to their irregular heartbeat, we needed to collect data from all phases of the cardiac cycle. The volume of contrast (Iopromide, 370mg/l of Ultravist®, Bayer) administered was adjusted according to weight and scanning time, using the formula: 25 × patient weight (kg) × scanning time (s)/contrast concentration (mg l/ml),8 with a flow rate of 5ml/s, followed by administration of a bolus of 40ml saline solution, at the same rate, using a dual-head delivery pump (Optivantage™ DH, Mallinckrodt). A bolus-tracking program (SUREStart™) was used with a slice acquisition rate of 1s until the contrast reached the defined threshold (200 Hounsfield units) and region of interest (ROI) in the LA. The study was performed in inspiratory apnoea and in a caudocranial direction to minimise respiratory movement and achieve correct opacification of the LA and complete wash-out of the right heart cavities.

Before terminating the scan, we checked the images acquired to confirm that complete opacification of the left atrial appendage had been achieved; if not, we performed delayed acquisition.

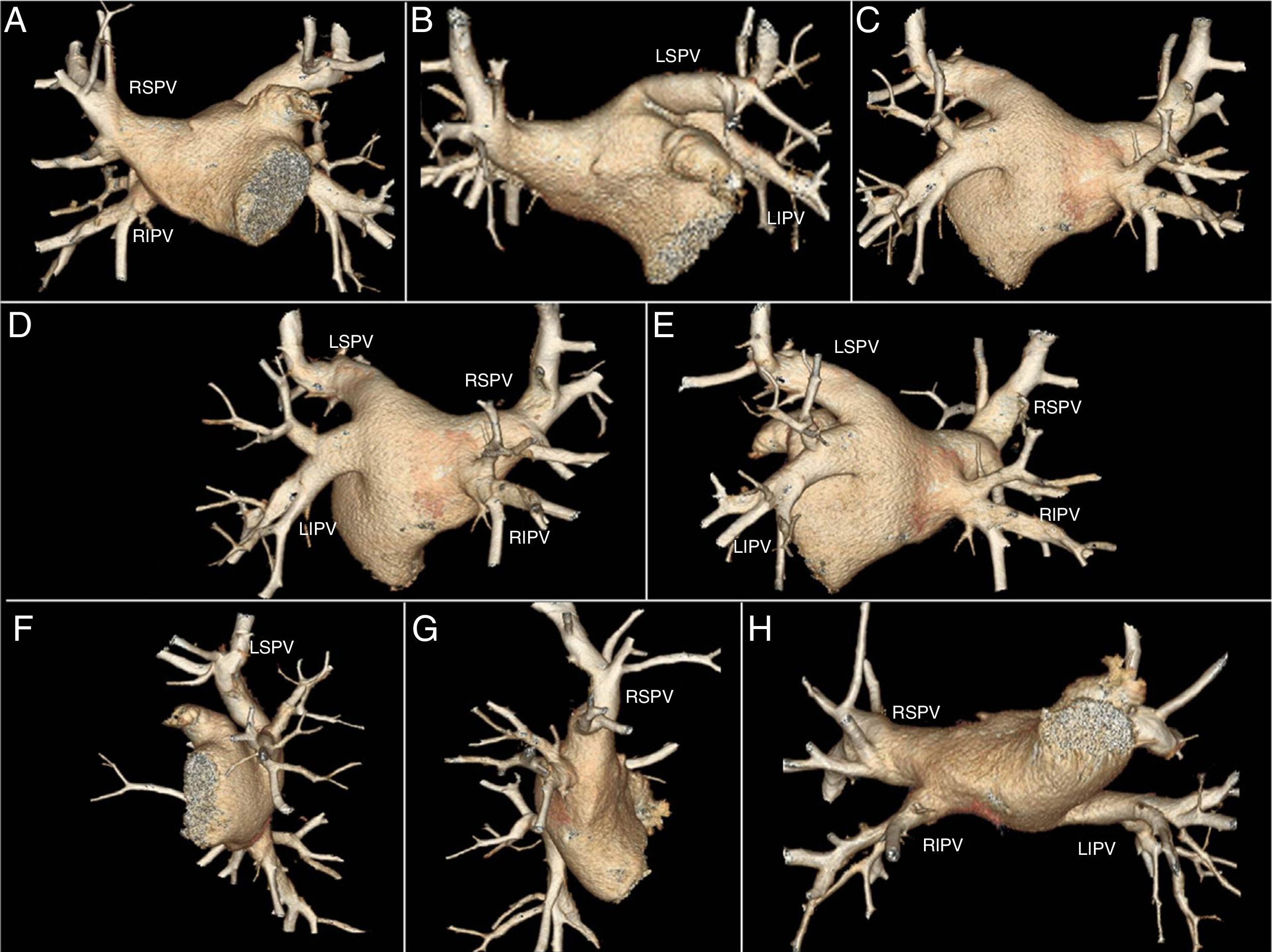

PostprocessingUsing volume rendering (VR) we obtained a three-dimensional map of the LA and PVs. We obtained eight epicardial views (Fig. 1), which allowed us to calculate the number of PVs in each patient. A normal pattern was defined as four PVs draining into the posterior wall of the LA, two right veins and two left veins. Accessory veins were those that presented an independent atriopulmonary connection to the PV and right common trunk (RCT) or left common trunk (LCT), when the proximal junction of the PVs drained into the LA with a single ostium.

Eight epicardial views obtained by volume-rendered images from a patient with 4 pulmonary veins. A) Anteroposterior 45° of cranial inclination. B) Anteroposterior 45° of caudal inclination. C) Posteroinferior 45° of cranial inclination. D) Right posterior oblique with 45° of cranial inclination. E) Left posterior oblique with 45° of cranial inclination. F) Left lateral with 45° of cranial inclination. G) Right lateral with 45° of cranial inclination. H) Inferior.

LIPV: left inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV: left superior pulmonary vein; RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV: right superior pulmonary vein.

Using multiplanar reconstructions (MPR), we calculated the ostial diameter, the ostium index (ratio), and the distance from the pulmonary vein to its first bifurcation:

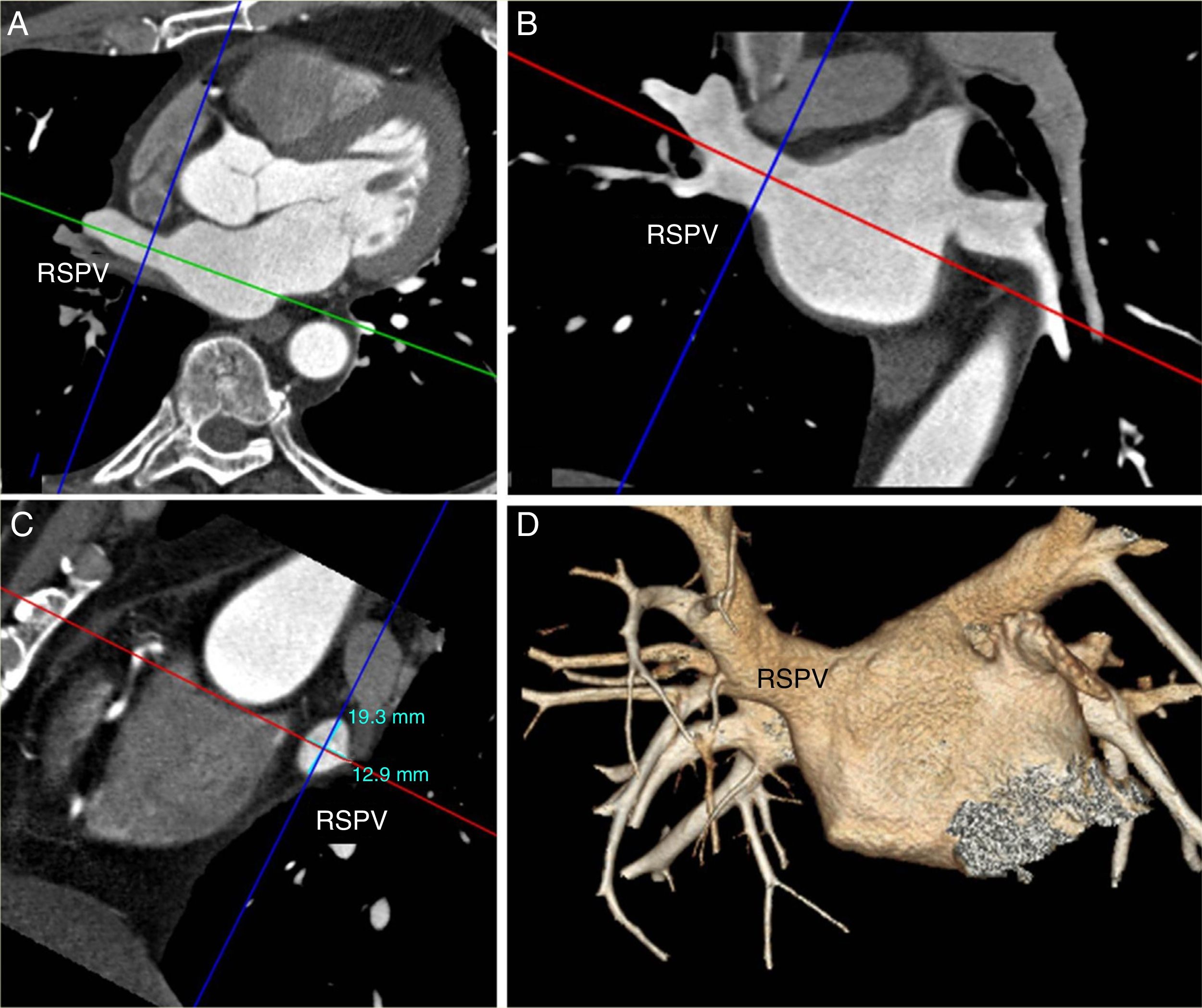

Ostial diameterIn the axial plane, we drew a vector through the long axis of the vein; we thus obtained transverse and oblique coronal images. Subsequently, using a vector perpendicular to the long axis, we obtained two diameters: anteroposterior diameter, or minimum diameter, and superoinferior diameter, or maximum diameter. The oblique sagittal image showed both diameters (Fig. 2).

Analysis of the diameters of the right superior pulmonary vein (RSPV). A) Oblique transverse multiplanar reconstruction. B) Oblique coronal with vector on the long axis of the RSPV (green in A and red in B). The anteroposterior diameter in A and the superoinferior diameter in B are obtained by drawing a vector perpendicular to the long axis (blue). C) Oblique sagittal multiplanar reconstruction showing both diameters. D) Anteroposterior volume rendering with 45° of caudal inclination.

For the statistical analysis, we used the maximum (Ømax), minimum (Ømin) and average (Ømax + Ømin/2) diameters.

Ostium index (ratio)We calculated the “shape” of the ostium on the basis of the ratio between two areas, the area of the circumference [= π · r2] and area of the ellipse [= π · a · b]. The area of the circumference was calculated using the minimum ostium diameter [= π · (Ømin/2)2], and the two semi-axes of the ellipse (a, b) were calculated using the minimum and maximum ostium diameters [= π · (Ømin/2) · (Ømax/2)].

Index=1 when the ostium was perfectly rounded. When the ratio approaches 1 the ostium is more rounded, when it deviates from 1 the shape is more oval.

Distance from the pulmonary vein to the first bifurcationMeasured in millimetres in an oblique coronal view. Distances were classified as short venous trunk or early bifurcation (distance <5mm) and long venous trunk (>5mm).

The presence of left atrial anomalies was evaluated: diverticulum (smooth wall sacculation and wide neck), accessory atrial appendage (irregular wall sacculation and narrow neck), atrial septal aneurysm (saccular protrusion of the atrial septum), septal defect/pouch (incomplete septal fusion with anterior oval fossa extension), and congenital coronary anomalies.

In cases where opacification of the left atrial appendage was incomplete, we performed a second delayed acquisition scan to rule out intracavitary thrombus.

The anatomical reconstruction of the LA was performed in the electrophysiology lab by merging the MDCT images using an EnSite-Velocity navigation system (EnSite™ NavX™; St Jude Medical).

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables were reported as mean, standard, minimum and maximum deviation, and qualitative variables were reported as relative frequencies.

Pearson’s χ2 test (or the likelihood ratio test or Fisher’s exact test, when the Pearson’s chi-square test was not valid) was used to determine the association between two qualitative variables.

The normality of the quantitative variables was estimated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. None of the data showed a normal distribution, so non-parametric tests were used.

The Mann-Whitney U test (two means) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (more than two means) were used to determine the association between a qualitative and quantitative variable (comparison of means).

The Friedman test was used for paired quantitative variables, and the Bonferroni adjustment was applied to all paired comparisons.

All statistical calculations were performed using the program IBM SPSS 24.0 Windows, and the α error was established at 0.050.

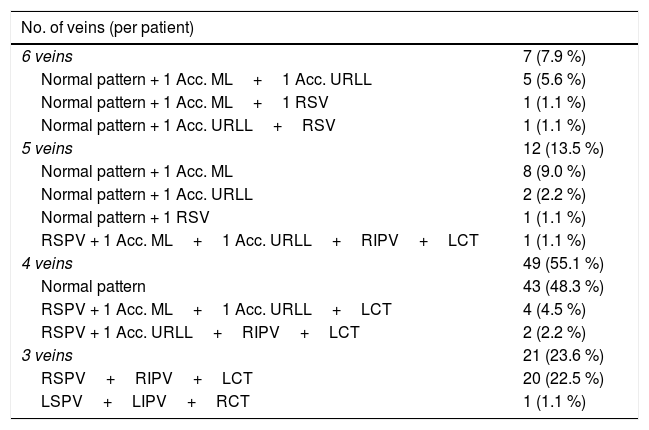

ResultsNumber and distribution of veinsTable 1 shows the number of PVs per patient and their distribution.

Number of veins per patient and their distribution.

| No. of veins (per patient) | |

|---|---|

| 6 veins | 7 (7.9 %) |

| Normal pattern + 1 Acc. ML+1 Acc. URLL | 5 (5.6 %) |

| Normal pattern + 1 Acc. ML+1 RSV | 1 (1.1 %) |

| Normal pattern + 1 Acc. URLL+RSV | 1 (1.1 %) |

| 5 veins | 12 (13.5 %) |

| Normal pattern + 1 Acc. ML | 8 (9.0 %) |

| Normal pattern + 1 Acc. URLL | 2 (2.2 %) |

| Normal pattern + 1 RSV | 1 (1.1 %) |

| RSPV + 1 Acc. ML+1 Acc. URLL+RIPV+LCT | 1 (1.1 %) |

| 4 veins | 49 (55.1 %) |

| Normal pattern | 43 (48.3 %) |

| RSPV + 1 Acc. ML+1 Acc. URLL+LCT | 4 (4.5 %) |

| RSPV + 1 Acc. URLL+RIPV+LCT | 2 (2.2 %) |

| 3 veins | 21 (23.6 %) |

| RSPV+RIPV+LCT | 20 (22.5 %) |

| LSPV+LIPV+RCT | 1 (1.1 %) |

Normal pattern: 4 main pulmonary veins (RSPV: right superior pulmonary vein; RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV: left superior pulmonary vein; LIPV: left inferior pulmonary vein).

Acc. ML: middle lobe accessory vein; Acc. URLL: accessory vein in the upper segment of the right lower lobe; LCT: left common trunk; RCT: right common trunk; RSV: right superior vein.

Seven patients presented six PVs (four right and two left), in which two right accessory veins were added to the normal four-vein pattern. Twelve patients presented five PVs, of which 11 had a normal pattern of four veins plus one right accessory vein, and one patient had four veins on the right side (right superior pulmonary vein [RSPV], right inferior pulmonary vein [RIPV] and two right accessory veins) and one left common trunk. Forty-nine patients presented four PVs; 43 had a normal vein pattern, and the remaining six had three right-sided veins (one RSPV) and one left-sided common trunk. Twenty-one patients presented three veins, which was due to an LCT in 20 patients and an RCT in one patient.

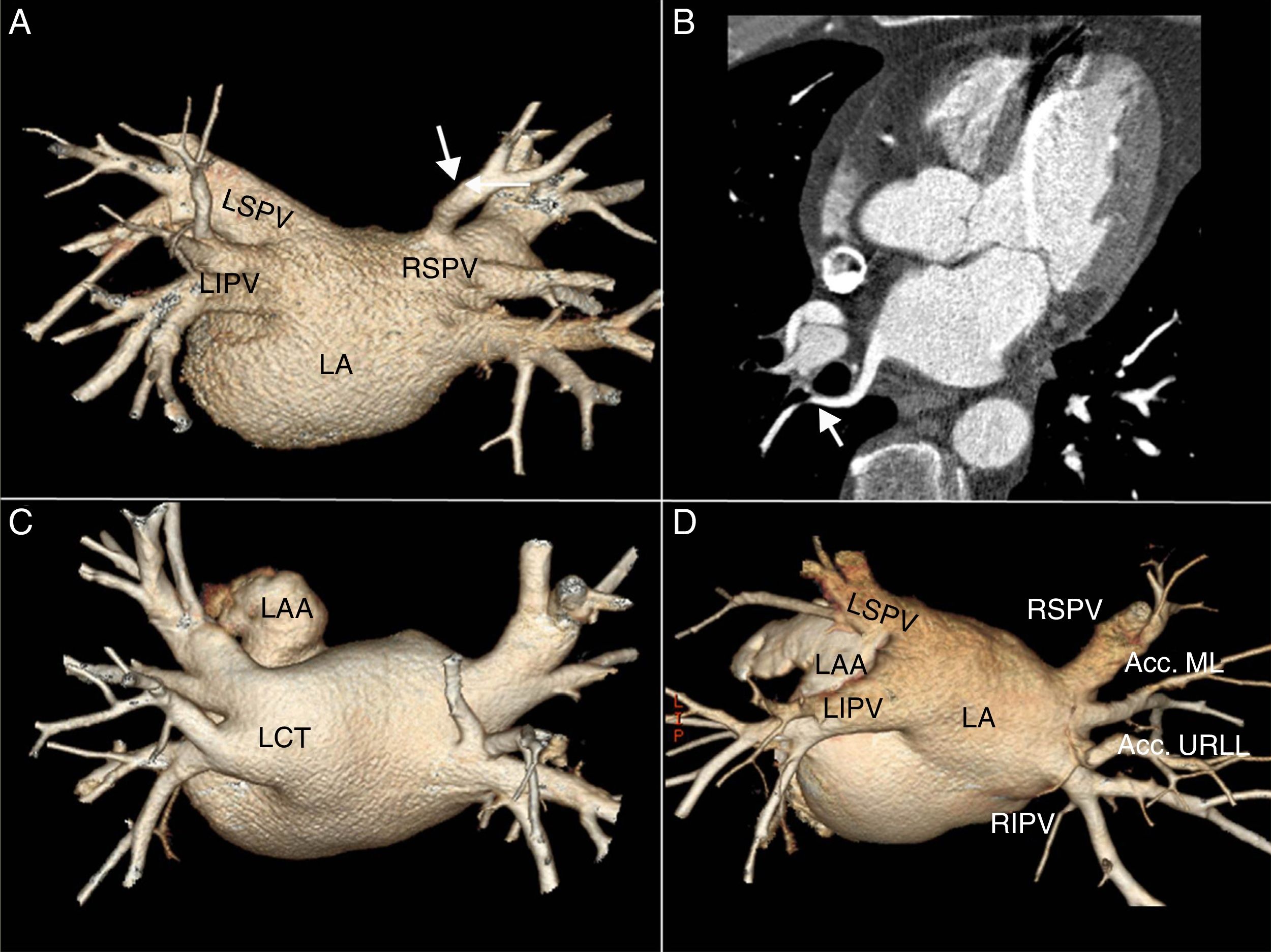

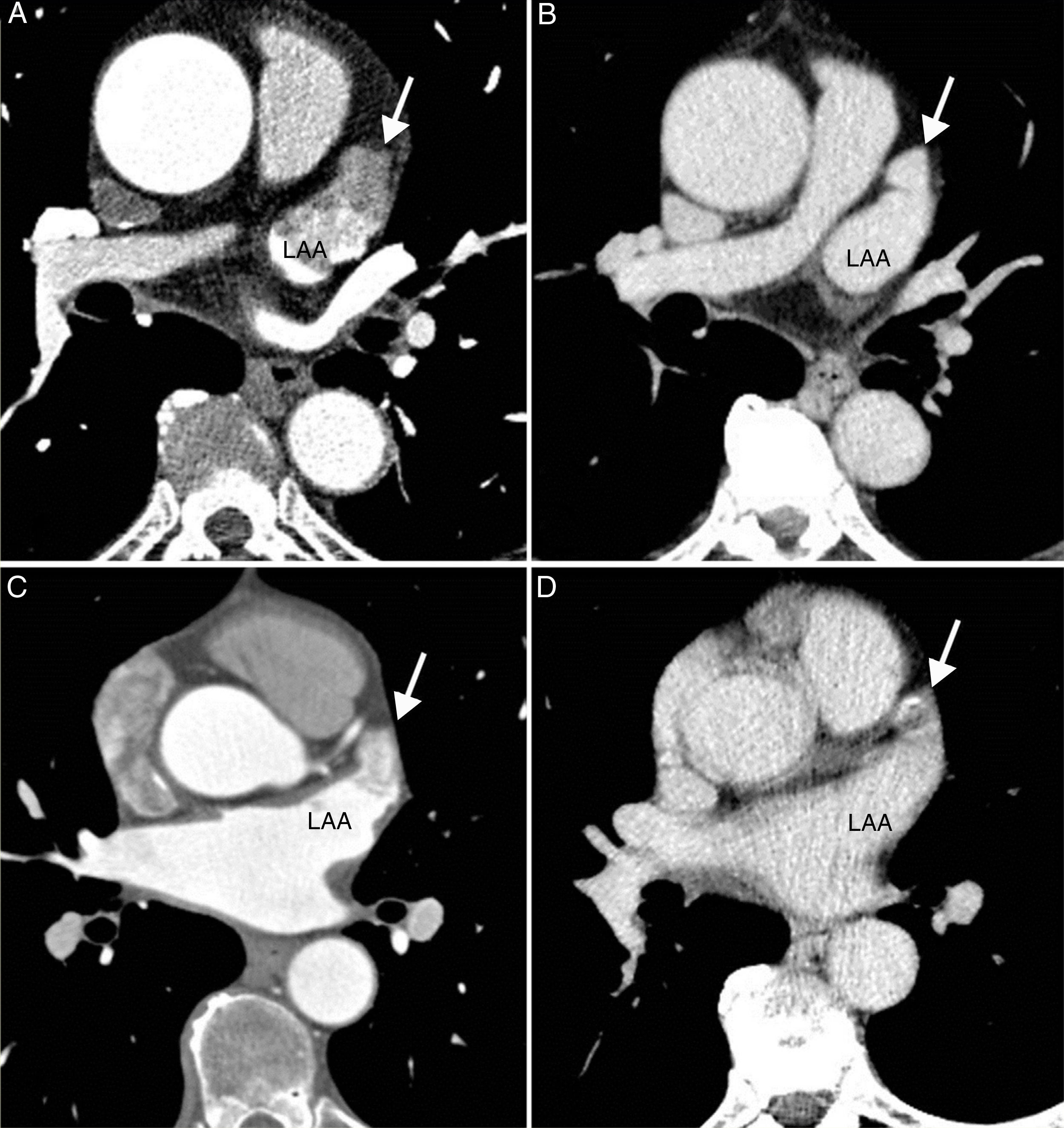

Accessory veins and common trunksAll accessory veins were right-sided, and were identified in 33 (37 %) patients: 19 (21.3 %) drained the middle lobe, 11 (12.3 %) the upper segment of the right lower lobe, and three (3.4 %) presented an superior right accessory vein that in all cases drained the upper segment of the right upper lobe. Six patients presented more than one right accessory vein (one accessory vein of the middle lobe and one accessory vein of the upper segment of the right lower lobe), 27 patients presented an LCT and one patient presented an RCT (Fig. 3).

A) Posteroanterior volume rendering with 45° cranial inclination, showing superior right accessory vein (white arrow) draining the posterior segment of the right upper lobe. B) Oblique transverse multiplanar reconstruction. Figure B shows the vein running behind the intermediate bronchus (white arrow). C) Left common trunk. D) Two right-sided accessory veins corresponding to an accessory vein of the middle lobe (Acc. ML) and an accessory vein of the upper segment of the right lower lobe (Acc. URLL).

LA: left atrium; LAA: left atrial appendage; RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV: right superior pulmonary vein.

None of our patients presented left-sided accessory veins or two common trunks.

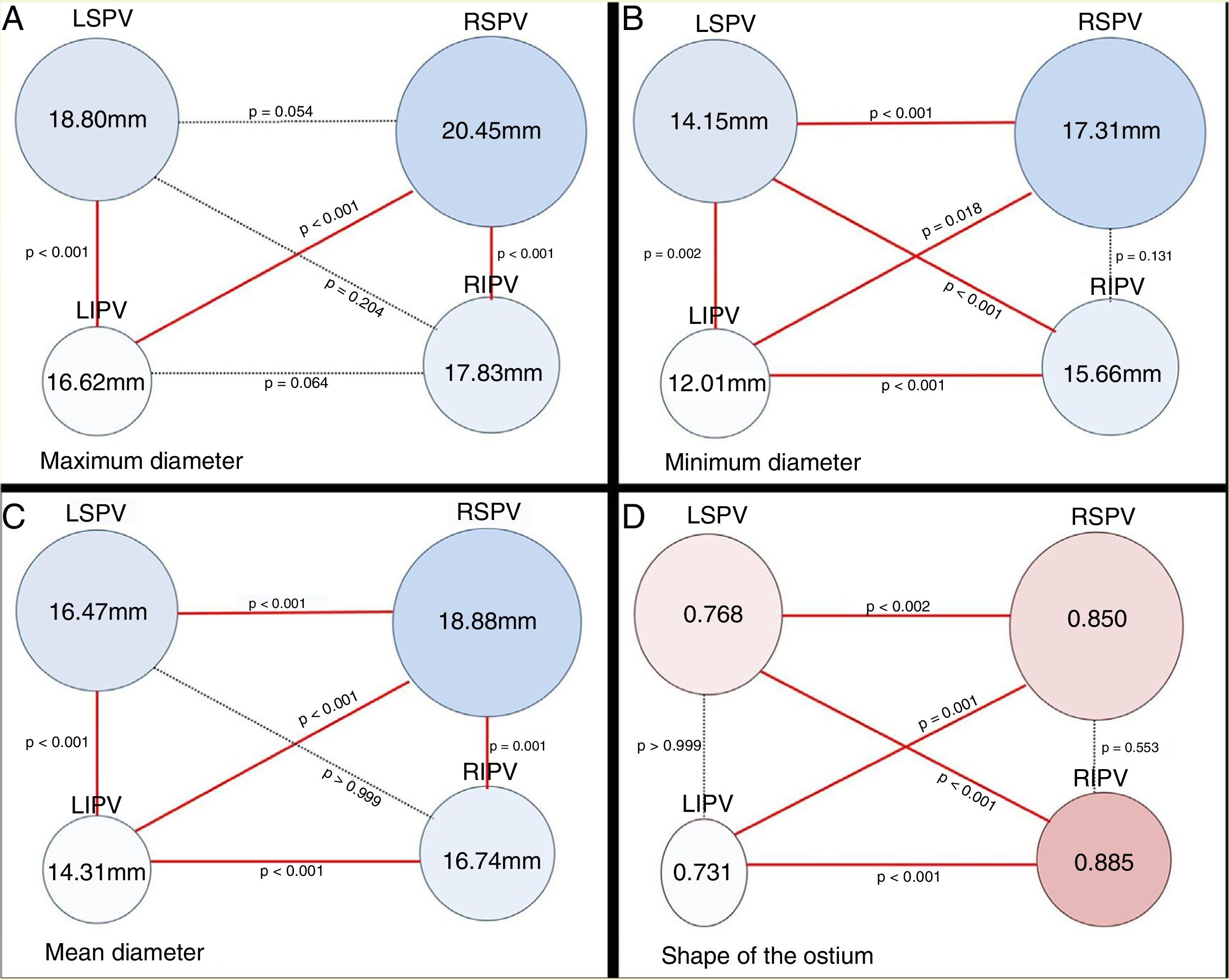

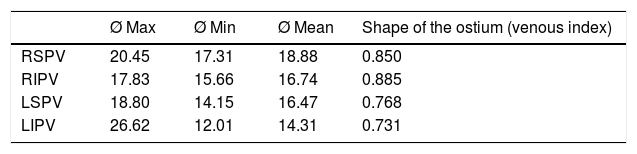

Diameter of the pulmonary vein ostiumTable 2 shows the maximum, minimum and mean diameters (expressed in millimetres) and the venous ostium indexes (“shape” of the ostium) of each main vein.

Maximum, minimum and mean diameters and ostium shape (in millimetres).

| Ø Max | Ø Min | Ø Mean | Shape of the ostium (venous index) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSPV | 20.45 | 17.31 | 18.88 | 0.850 |

| RIPV | 17.83 | 15.66 | 16.74 | 0.885 |

| LSPV | 18.80 | 14.15 | 16.47 | 0.768 |

| LIPV | 26.62 | 12.01 | 14.31 | 0.731 |

LIPV: left inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV: left superior pulmonary vein; RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV: right superior pulmonary vein.

A comparison of the diameter of the ostia of the superior and inferior PVs and their shape (Fig. 4) reveals considerable differences.

Diagram of the pulmonary vein (PV) ostia in posteroanterior view. Analysis of ostium ratio using the maximum (A), minimum (B) and mean (C) diameters. Figure D shows the shape of the PV ostia based on the venous ostium ratio. Ostium ratio: ratio between two areas, the area of the circumference [= π · r2] and area of the ellipse [= π · a · b]. The area of the circumference area was calculated using the minimum ostium diameter [= π · (Ømin/2)2], and the two semi-axes of the ellipse (a, b) were calculated using the minimum and maximum ostium diameters [= π · (Ømin/2) · (Ømax/2)]. Index=1 when the ostium is perfectly rounded. The ostium was more rounded when the index was closer to 1, and more oval when the index was furthest from 1.

Taking the maximum ostium diameter as a reference, we found that the ostia of the superior PVs were significantly larger than those of the inferior PVs (RSPV>RIPV; p<0.001 and left superior pulmonary vein [LSPV] > left inferior pulmonary vein [LIPV]; p<0.001) and that the maximum diameter of the ostium of the RSPV was larger than that of the LIPV (p<0.001). We found no differences in size between the ostia of the RSPV and LSPV or between the ostia of the RIPV and LIPV (p=0.064).

In terms of the minimum diameter, the ostia of the right PVs were significantly larger than the left PVs (RSPV>LSPV; p<0.001 and RIPV > LIPV; p<0.001) and the minimum ostium diameter of the LSPV was larger than that of the LIPV (p=0.002). There were no differences between the diameters of the right-sided ostia (p=0.131). The minimum diameter of the RSPV was significantly larger than that of the LIPV (p=0.018), and the minimum diameter of the RIPV was larger than that of the LSPV (p<0.001).

In terms of the mean ostium diameter, the ostium of the RSPV (18.88mm) was significantly larger than the other PVs (RIPV: 16.74mm; p=0.001; LSPV: 16.47 mm; p<0.001 and LIPV: 14.31 mm; p<0.001). The superior PVs presented a larger ostium diameter than the inferior PVs (RSPV > RIPV; p=0.001 and LSPV > LIPV; p<0.001). The right-sided PVs presented a larger ostium diameter than the left-sided PVs (RSPV > LSPV; p<0.001 and RIPV>LIPV; p<0.001).

The RIPV presented the most perfectly rounded ostium (ratio: 0.885) with respect to the LIPV (ratio: 0.731; p<0.001) and the LSPV (ratio: 0.768; p<0.001). The ostia of the right-sided PVs were more rounded than the left-sided PVs (RSPV ratio: 0.850 and LSPV ratio: 0.768; p=0.002. RIPV ratio: 0.885 and LIPV ratio: 0.731; p<0.001).

Comparing ostium diameter with gender only showed differences in the maximum diameter: we observed that the maximum diameters of the right-sided PVs are larger in men vs. women (p=0.009 in RSPV; p=0.050 in RIPV). The ostium of the RSPV was more rounded in women than in men (p=0.033).

Distance to the first bifurcationThe distances from the ostium of each PV to its first (mean) bifurcation were 7.90mm in the RSPV, 4.49mm in the RIPV, 14.72mm in the LSPV, and 11.72mm in the LIPV.

The distance to the first bifurcation was greater in the superior vs. the inferior PVs (RSPV distance>RIPV distance; p=0.008 LSPV distance >LIPV distance; p=0.038). The distance to the first bifurcation was greater in the left-sided PVs vs. right-sided PVs (LSPV distance > RSPV distance; p<0.001 and LIPV distance > RIPV distance; p<0.001). The distance to bifurcation was greatest in the LSPV and least in the LIPV.

When we classified these distances as short trunk (<5mm) and long trunk (>5mm), women presented a higher percentage of short-trunk LSPVs compared to men (p=0.029). Short-trunk PVs were significantly more prevalent in patients with three or six veins (p=0.011).

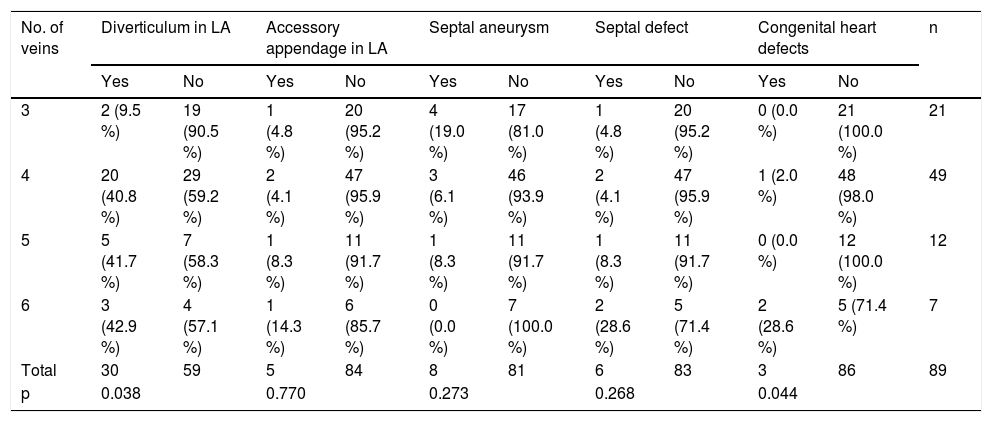

Associated anomaliesThirty patients (33.7 %) presented diverticula in the anterosuperior wall of the LA; five (5.6 %) with accessory atrial appendages on the lower left wall; and eight (9 %) with atrial septal aneurysms; six (6.7 %) with septal pouches (Fig. 5) and three (3.4 %) presented congenital heart defects: two patients with high coronary ostia and one patient with an anomalous origin of the circumflex artery in the right coronary artery extending behind the aorta.

Findings in the left atrium (LA). A) Oblique transverse reconstruction showing a saccular defect (black arrow) in the right anterosuperior wall of the LA, with a smooth contour and broad base, corresponding to a diverticulum. B) Sagittal oblique reconstruction showing a saccular defect in the lower right lateral wall of LA (white arrow), with an irregular contour, corresponding to an atrial accessory appendage. C) Oblique transverse reconstruction showing a pouch deformation in the atrial septum, in the region of the foramen ovale (white arrow), corresponding to an aneurysm. D) Oblique transverse reconstruction showing a defect/septal pouch in the left atrial wall that appears as a thin septum and corresponds to a patent foramen with no evidence of contrast crossing over to the right cavity (circle).

When we analysed these anomalies with respect to the number of PVs (Table 3), we observed a very low incidence of LA diverticula in patients with three PVs, while an equal proportion of patients with four, five or six PVs either did or did not present diverticula (p=0.038). It is also significant that most of the congenital heart defects appeared in patients with six veins (p=0.044).

Relationship of atrial anomalies with the number of veins.

| No. of veins | Diverticulum in LA | Accessory appendage in LA | Septal aneurysm | Septal defect | Congenital heart defects | n | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| 3 | 2 (9.5 %) | 19 (90.5 %) | 1 (4.8 %) | 20 (95.2 %) | 4 (19.0 %) | 17 (81.0 %) | 1 (4.8 %) | 20 (95.2 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 21 (100.0 %) | 21 |

| 4 | 20 (40.8 %) | 29 (59.2 %) | 2 (4.1 %) | 47 (95.9 %) | 3 (6.1 %) | 46 (93.9 %) | 2 (4.1 %) | 47 (95.9 %) | 1 (2.0 %) | 48 (98.0 %) | 49 |

| 5 | 5 (41.7 %) | 7 (58.3 %) | 1 (8.3 %) | 11 (91.7 %) | 1 (8.3 %) | 11 (91.7 %) | 1 (8.3 %) | 11 (91.7 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 12 (100.0 %) | 12 |

| 6 | 3 (42.9 %) | 4 (57.1 %) | 1 (14.3 %) | 6 (85.7 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 7 (100.0 %) | 2 (28.6 %) | 5 (71.4 %) | 2 (28.6 %) | 5 (71.4 %) | 7 |

| Total | 30 | 59 | 5 | 84 | 8 | 81 | 6 | 83 | 3 | 86 | 89 |

| p | 0.038 | 0.770 | 0.273 | 0.268 | 0.044 | ||||||

Three of the 89 patients presented contrast filling defects in the left atrial appendage, and, therefore, a second delayed acquisition scan was performed. Opacification was homogeneous in two cases, but the defect persisted in the third patient, confirming the presence of thrombus (Fig. 6).

False thrombus (A and B). A) Axial slice with filling defect in the left appendage (white arrow). B) Delayed acquisition with complete opacification of the appendage (white arrow). Thrombus (C and D). C) Axial slice with filling defect in the left appendage (white arrow). D) Delayed acquisition with persistence of the filling defect (white arrow). LAA: left atrial appendage.

AF is the most common arrhythmia in adults, with an overall prevalence of 0.4 %.9 Part of the LA myocardium that extends like a sleeve over the proximal segment of the PV is responsible for ectopic foci.2,6

Catheter ablation of the arrhythmogenic foci of the distal PVs has been a major therapeutic breakthrough, and prevented recurrence of AF in 70–80 % of patients during the first year of follow-up.10

PVs must be selectively catheterised before they can be electrically treated. New technologies have replaced fluoroscopy to define the PV ostia, as the latter does not provide an adequate three-dimensional image of the pulmonary venous anatomy, and good outcomes depend not only on successful ablation, but also on minimising exploration time and the risk of complications. Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE), MDCT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) all show the anatomy of the PVs and LA before the procedure, and choosing one or the other will depend on the radiologist’s clinical experience and the availability of the device.11 All three techniques reduce the duration of the procedure, recurrence of AF and radiation exposure.12

MDCT and MRI are superior to TOE in identifying the anatomy of PVs, measuring the ostia, and in superimposing images over electroanatomic maps.13–15 MDCT has the shortest exploration time and does not require sedation.

Pulmonary venous anatomy was visualised correctly in all patients. The normal pattern of four PVs was found in 43 patients (48.3 %). The prevalence of normal-pattern PVs varied from 57 % to 82 % among the studies reviewed.16 This could be due to either lack of consensus in the definition of ostium, or to the different imaging techniques used.17

Accessory veins, with their smaller ostia, may be overlooked during the procedure and cause recurrent AF.18 A review of the published scientific literature has shown an incidence of between 4 % and 27 % of right-sided accessory veins,15 in contrast with the 37 % observed in our study. The prevalence of two right-sided veins in the same patient was lower, at 6.7 %, and is similar to the rate found in other studies.19

A right superior vein (RSV) is a very rare accessory vein. First described by von Haller,20 it consists of a supernumerary vein with an ostium in the upper right region of the LA, medial to the ostium of the RSPV, and runs posterior to the intermediate bronchus. It is important to identify this vein during the procedure to prevent it becoming accidentally blocked by the catheter. In our study, the RSV was identified in three patients (3.4 %), a frequency similar to other studies.21

Twenty-seven patients (30.3 %) presented a left common trunk, and one patient (1.1 %) a right common trunk. The frequency of this finding varies greatly from 3 % to 83 % on the left side18,21,22 and from 2 % to 39 % on the right side.17,23

The diameter of the ostium is a critical factor in selecting the appropriate catheter size, since a small diameter is more prone to post-tabulation stenosis.

The accuracy of the diameter measurement depends on the imaging technique used and the plane where it is measured. Conventional angiography overestimates the diameter, and transoesophageal echocardiography underestimates it compared to MDCT and intracardiac echocardiography, which provide the best ostial measurements.22

We classed the ostial diameters found in our patients as maximum, minimum and mean. Of the three, we found a greater number of significant results with the mean diameter, with the ostia of the right veins being greater than that of the left veins.16,24 In some studies, the authors found no differences between the right and left veins,25 since the ostial measurements were performed on volume-rendered images that only measured the maximum diameter, defined as the intersection of tangents from the upper and lower margin of the pulmonary vein with respect to the wall of the LA.

Of all the PVs in our subjects, the vein with the greatest ostial diameter was the RSPV (18.88mm), a finding which is similar to other studies.26

Although the PV ostia tend to be larger in men than in women, in our study this difference was only significant in the maximum diameter of the right-sided ostia. Our literature review showed contrasting results. In one study, the ostial diameter of the inferior PVs was greater in men,16 while in another, the ostium of LSPV was greater in men than in women.26

The oblique sagittal plane provides the most reproducible ostial measurements because it facilitates the measurement of two diameters, the maximum and the minimum, since the ostium is not perfectly rounded.27 We calculated the venous ostium index (ratio) in order to evaluate the shape of the ostium. According to this ratio, the ostium of the left PVs is more oval than that of the right PVs, and the more rounded ostia are found in the right-sided veins, a finding consistent with the published literature.22,26–28 In our study, the ostium of the LIPV was more frequently oval in shape, since it is compressed by the wall of the descending aorta and the wall of the LA as it enters the posterior wall of the LA.26

It is essential to measure the distance from the ostium to the first bifurcation to ensure there is adequate space for ablation. If the first bifurcation is less than 5mm away, there is a risk of stenosis.15,29 In our study, the distance in the left-sided PVs was 5mm greater with respect to right-sided veins. The greatest distance, 14.72mm, was observed in the LSPV, a finding similar to other studies.16,19

Diverticula and accessory appendages are anatomical variants. A 2017 study that evaluated the presence of diverticula in patients before PV ablation30 reported a high prevalence of diverticula of 43.2 %. Diverticula may be associated with arrhythmias, thromboembolism or mitral regurgitation,31 and should be borne in mind as a possible cause of complications during ablation, such as catheter entrapment, perforation or thrombus formation.28,30 Other studies have found a higher frequency in men, but no statistically significant differences in terms of gender.31 We also found a higher frequency in men (37.3 % vs. 26.7 %), but no significant differences. Interestingly, diverticula were rarely found in patients with three pulmonary veins.

It is important to detect atrial septal aneurysms, because they have been associated with atrial tachyarrhythmias and thrombus formation.32 Due to the wide availability of echocardiography, this anomaly is frequently detected,5 although it is rare in the adult population (2.2 %).33 We observed a higher frequency (9 %) of atrial septal aneurysms in our patients.

Septal defects or pouches in the atrium may cause thrombi.33 These anomalies are diagnosed using MDCT and MRI. We found an incidence of 6.7 % among our patients.

The presence of thrombus in the left atrial appendage is an absolute contraindication for ablation. MDCT has greater sensitivity than MRI in the detection of intracavitary thrombi; in these cases, therefore, TOE is the most sensitive imaging technique.

Although TOE is still the gold standard technique for definitively ruling out thrombus, MDCT has recently gained ground in this respect. Studies comparing MDCT with TOE have shown that MDCT has an excellent negative predictive value (98 %) and a specificity of 85–88 %,34 although sensitivity varies from 29 % to 1.0 %.35,36 If the left atrial appendage is completely opacified in the arterial phase, the presence of thrombus is highly unlikely. If a filling defect is observed, delayed acquisition can be performed to differentiate between a thrombus (the defect persists) and slow flow (the defect disappears).37 We performed delayed acquisition in three patients in our series due to lack of opacification of the left atrial appendage in the arterial phase. In one patient, the defect persisted, so we identified it as a thrombus, and ablation was delayed for one year.

ConclusionA detailed study of PVs in terms of their anatomical pattern, branching pattern, orientation and diameter of the ostium, and relationship with the LA will provide an essential anatomical map prior to the interventional procedure. MDCT is a widely available, easily reproducible non-invasive technique that can show the anatomy of the PVs and surrounding structures in three dimensions. These characteristics make it the ideal tool for evaluating the LA and PVs both before and after ablation. Our study shows the anatomical differences found in the PVs and their ostia, and the statistically significant differences between them in terms of pattern and size.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: EAH.

- 2.

Study conception: EAH, MEGS and DYR.

- 3.

Study design: EAH, DYR and MEGS.

- 4.

Data collection: EAH, MEGS and PSM.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: EAH, MEGS and DYR.

- 6.

Statistical processing: EAH and ACS.

- 7.

Literature search: PSM, ACS and MENM.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: EAH, PSM and MENM.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: DYR.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: EAH, MEGS and DYR.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Angulo Hervias E, Guillén Subirán ME, Yagüe Romeo D, Casán Senar A, Seral Moral P, Núñez Motilva ME. Tomografía computarizada multidetector en la planificación del tratamiento de la fibrilación auricular. Radiología. 2020;62:148–159.

![Diagram of the pulmonary vein (PV) ostia in posteroanterior view. Analysis of ostium ratio using the maximum (A), minimum (B) and mean (C) diameters. Figure D shows the shape of the PV ostia based on the venous ostium ratio. Ostium ratio: ratio between two areas, the area of the circumference [= π · r2] and area of the ellipse [= π · a · b]. The area of the circumference area was calculated using the minimum ostium diameter [= π · (Ømin/2)2], and the two semi-axes of the ellipse (a, b) were calculated using the minimum and maximum ostium diameters [= π · (Ømin/2) · (Ømax/2)]. Index=1 when the ostium is perfectly rounded. The ostium was more rounded when the index was closer to 1, and more oval when the index was furthest from 1. Diagram of the pulmonary vein (PV) ostia in posteroanterior view. Analysis of ostium ratio using the maximum (A), minimum (B) and mean (C) diameters. Figure D shows the shape of the PV ostia based on the venous ostium ratio. Ostium ratio: ratio between two areas, the area of the circumference [= π · r2] and area of the ellipse [= π · a · b]. The area of the circumference area was calculated using the minimum ostium diameter [= π · (Ømin/2)2], and the two semi-axes of the ellipse (a, b) were calculated using the minimum and maximum ostium diameters [= π · (Ømin/2) · (Ømax/2)]. Index=1 when the ostium is perfectly rounded. The ostium was more rounded when the index was closer to 1, and more oval when the index was furthest from 1.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735107/0000006200000002/v1_202003050649/S2173510719301065/v1_202003050649/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)