Suplement “Update and good practice in the contrast media uses”

More infoIodinated contrast media enable greater attenuation of vascular and visceral structures in radiological studies and are widely used due to their high degree of safety, easy administration, acceptable level of tolerance, wide distribution and rapid excretion, qualities determined by their composition.

Automated power injectors are used to administer contrast media. Once injected, contrast is distributed throughout the body, remaining in the intravascular space during its first passage before reaching the organs and spreading into the extracellular interstitial space, followed by a recirculation phenomenon.

In CT studies, the level of contrast enhancement obtained is determined by multiple factors including patient-related factors, contrast medium characteristics, method of administration, equipment and technique. Different methods are available for determining the scan timing depending on the aim of the exploration.

Los medios de contraste yodados permiten obtener una mayor atenuación de las estructuras vasculares y viscerales en los estudios radiológicos y son ampliamente utilizados por su buen perfil de seguridad, fácil administración, aceptable tolerancia, amplia distribución y rápida excreción que vienen determinadas por su composición.

La administración de los medios de contraste se realiza mediante bombas automáticas. Una vez inyectados, se distribuyen en el organismo, en un primer paso intravascular, para posteriormente alcanzar los órganos y difundir al espacio intersticial extracelular, acompañado de un fenómeno de recirculación.

En un estudio de TC, la atenuación obtenida con un medio de contraste vendrá determinada por múltiples factores que dependen del paciente, características del medio de contraste, su forma de administración, del equipo y técnica empleados para el estudio. Existen diferentes métodos para determinar el retraso con el que se inicia la adquisición, que dependerá del objetivo de la exploración.

Iodinated contrast media (ICM) are widely used in diagnostic radiology because of their high levels of safety, easy administration, accepted tolerance levels, broad applicability and rapid excretion. They are mostly used in computed tomography (CT), angiographies and imaging studies of the intestinal or urinary systems. They are positive contrast agents due to their ability to increase x-ray attenuation in organs and vascular structures.

Evolution of iodinated contrast media: backgroundContrast media (CM) were first used by Haschek et al. who obtained the first angiography by injecting a mercury, paraffin and lime-based medium into an amputated hand1 just one month after the discovery of x-rays. Iodine was first used as a radiological contrast agent in urographic studies initially through a catheter in the 1920s,2 and later intravenously.3 Other elements such as mercury, thorium, silver and lead were discarded due to their toxicity.

The first ICM were quite toxic, but in the 1920s less toxic and more soluble versions came into widespread use, such as Selectan® and Uroselectan®. Subsequent reformulations resulted in the high-osmolar ionic ICMs that are used today.4 In 1969, a Swedish radiologist, Torsten Almén, was concerned about the pain experienced by some patients with the administration of ionic ICMs and thus developed the first low-osmolar non-ionic ICM (metrizamide),5 laying the foundation for the development of new ICM.

CompositionThe different ICM molecules are formed by a benzene ring with three iodine atoms that alternate with three side chains (Fig. 1), resulting in a stable drug and a reduced risk of the toxicity that can be caused by the release of iodine.

The iodine radicals interact with the x-rays and this causes increases in attenuation, as will be discussed.

The radicals associated to the three remaining carbon atoms increase the solubility of the molecule and facilitate its elimination. Depending on its composition, these radicals may or may not be associated with ionic charges, which is what determines whether they form ionic or non-ionic contrasts and their different physiochemical characteristics.

Initially, ICM were formed by one benzene ring (monomers) while dimeric contrasts (with two benzene rings) were developed later. Ionic dimers can contain six iodine atoms in a single molecule, changing its properties and increasing its radiation attenuation.6

Like other drugs, ICMs also contain excipients, mainly to maintain a neutral or blood-like pH, avoiding disturbance of acid-base balance or vascular irritation.7

Physiochemical propertiesSolubilityICM have to be water-soluble for intravascular administration and this is facilitated by the radicals associated to the benzene. This can be achieved in two ways: with salt-like radicals which have significant effects on the ionicity and osmolality, as will be discussed (sodium amidotrizoate and meglumine amidotrizoate); or with hydroxyl, ether and/or amide-type radicals, which interact with water molecules to increase hydrophilicity (iohexol).

IonicityIodinated contrasts can be ionic or non-ionic.

Ionic contrasts were the first to be developed. To increase solubility, one of the radicals consists of a salt bound to a molecule (sodium, meglumine or calcium), which upon dilution dissociates, resulting in two molecules: on the one hand an anion (benzene and ring and iodine) and on the other a cation (Fig. 1B).

Non-ionic contrasts have other molecules to increase solubility, and upon dilution, they dissociate and do not produce ionic charges.

Both can be monomers or dimers depending on whether they have one or two benzene rings in their molecule.

OsmolalityOsmolality corresponds to the concentration of a solution, defined as the number of particles per unit of solvent in kilograms.

Iodinated contrasts generally have higher osmolality than blood (290 mOsm/kg). They are classified as high-osmolar (four to seven times the osmolality of blood, greater than 1400 Osm/kg), low-osmolar (about twice the level of blood, 400–800 mOsm/kg) and iso-osmolar (osmolality similar to that of blood).

When monomeric ionic ICM dissolve, they dissociate into two particles, which leads to an increase in particles in solution and therefore in osmolality, which is related to a higher rate of adverse events, such as nephrotoxicity.8,9 Therefore, the intravascular administration of ionic contrasts has decreased, and preference has shifted to enteric or intracavitary contrasts. Ionic dimers produce fewer particles in solution at equal iodine concentration than monomers, resulting in low-osmolar contrasts (Table 1).

Osmolality is also related to the iodine concentration of each commercial product (expressed in mg/ml iodine), with osmolality increasing with concentration (due to an increase in the number of molecules per ml).

ViscosityViscosity refers to the resistance of a fluid to deformation. This property depends on the size of the molecule (higher viscosity in dimers), concentration (the higher the concentration, the higher the viscosity), solubility and temperature (increases as temperature decreases).

Increased viscosity leads to a slowing of microcirculation, which may be related to renal damage,10 and affects the speed of administration. To reduce these effects, contrasts are warmed prior to administration.

Iodine contentThe attenuation capacity of iodinated contrast depends, among other factors, on the amount of iodine in the contrast, being higher per molecule in dimeric contrasts than in monomers. The amount of iodine also depends on the strength of the chosen pharmaceutical formulation and the volume of contrast administered.

Classification of iodinated contrast media and their presentationsAs we have discussed, contrasts can be classified as ionic monomers, ionic dimers, non-ionic monomers or non-ionic dimers (Table 1). Table 2 shows the most common contrasts.

Examples of iodinated contrast media commonly used in our setting.

| Composition | Active principle | Commercial names | Osmolality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic monomer | Meglumine amidotrizoate | Radialar® | High |

| Sodium amidotrizoate and meglumine amidotrizoate | Trazograf® Urografín® Pielograf ® Gastrografín ® | ||

| Meglumine amidotrizoate, sodium amidotrizoate and calcium amidotrizoate | Plenigraf® | ||

| Ionic dimer | Ioxaglate meglumine | Hexabrix® | Low |

| Non-ionic monomer | Iopamidol | Scanlux® Iopamigita® Iopamiro® | Low |

| Iohexol | Omnipaque® Iohexol® Omnitrast® | ||

| Iobitridol | Xenetix® | ||

| Iomeprol | Iomeron® | ||

| Ioversol | Optiray® | ||

| Iopromide | Ultravist® Clarograf® | ||

| Non-ionic dimer | Iodixanol | Visipaque® | Iso-osmolar |

Lipiodol is also occasionally used. This is a liposoluble iodinated contrast historically used in bronchography, hysterosalpingography and myelography. It is hardly used today except for in lymphangiography and occasionally in hepatic chemoembolisation.4

ICM can range in concentration from 200 to 400 mgI/ml. There are also different forms of presentation, including single-dose and multi-dose packs, usually 500 ml, as well as pre-filled syringes.

The physics of X-ray attenuation by iodinated contrastCT scan images represent the attenuation of the x-ray beam as it passes through the target tissues. The attenuation coefficient of the tissues represents the ability to reduce the intensity of incident radiation and is obtained by measuring the amount of radiation that reaches the detectors after passing through the tissues and comparing it with the amount of radiation emitted. This depends on the material, its atomic number (Z) and density, and the energy of the incident beam.

Typically, a potential difference of 120 kVp is used, which generates a radiation beam with a continuous spectrum of energies from 0 to 120 keV, which interacts with the material it passes through. The two main interactions that occur in this energy range are the photoelectric effect and Compton scattering,11–13 which are depicted in Fig. 2.

The photoelectric effect results from the interaction of the photon with an electron in the innermost layers with the highest binding energy. The K-layer is the most tightly bound to the nucleus. The photon is absorbed and the electron is released. For this interaction to occur, the energy of the photon must be higher than the binding energy of the electron shell to the nucleus. The probability of this effect increases with keV values slightly above the k-layer binding energy, known as the ‘K-edge’. This binding energy varies for each element and increases with a higher atomic number. The higher the density of elements with high Z, the more likely that the photoelectric effect occurs.

Compton scattering is produced when the outermost and quasi-free electrons interact. In this phenomenon, the incident photon changes direction and gives part of its energy to the electron.

In studies conducted at low potential differences (40–70 kVp) or when we use spectral technology to analyse information obtained at low energy, we approach the K-edge of iodine, where the photoelectric effect dominates. Conversely, this effect diminishes as the kilovoltage increases (140–200 kVp).11–13

In clinical practice, contrast-enhancing vessels and tissues interact more with the x-ray beam due to a higher photoelectric effect. This results in a higher attenuation compared to other structures, a phenomenon that increases at lower kVp.

With the use of different spectral CT equipment and post-processing software, monoenergetic images can be obtained from 40 keV, where the photoelectric effect predominates and the attenuation of vessels and tissues increases, especially when we use ICM to improve visualisation. By contrast, at higher values (greater than 140 keV), the photoelectric effect decreases and there is less attenuation of the structures, resulting in a reduction of artifacts.14–16

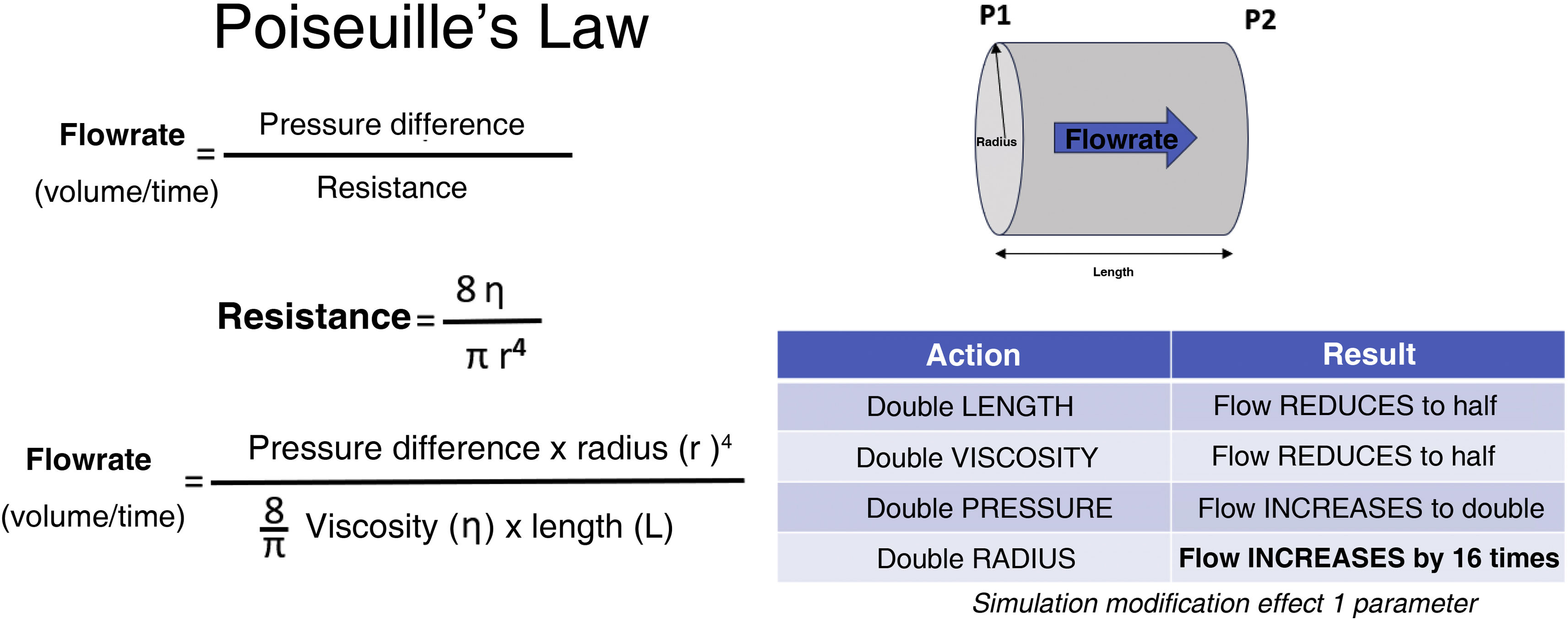

Power injectors and their possible usesIn the early days, CM was administered by infusion or manual injection. This proved ineffective for the catheterisation of vessels which required an increased injection pressure that could not be maintained for large volume administration. The flow through a hollow cylindrical tube, such as an intravascular catheter, is determined by Poiseuille's Law (Fig. 3) which determines that the pressure required to guarantee the flow rate is influenced by the viscosity of the element to be infused, and the length and radius of the tube.17 As has been shown, viscosity depends on the chemical structure of the ICM and is proportional to its concentration and inversely proportional to its temperature.

Determinants of flow through catheter.

Adapted from.17

For these reasons, power injectors were introduced into radiological practice.17 From the outset, two technologies have been used18: piston technology, similar to that of a normal syringe in which a plunger pushes the ICM or solution, and peristaltic technology, in which the contents are transported by the rotation of a mechanism that compresses the tubing through which the substance transits (Fig. 4).

Contrast injection systems serve a triple purpose in routine care: they distance the operator from the point of administration, thus minimising radiation exposure; they ensure an adequate injection in terms of flow; and they facilitate the reproducibility of injections.

High-flow injections used to cause a greater number of adverse effects, particularly nausea, and so non-ionic CM are now preferred because of their lower osmolality. However, given the greater expense of the latter, Hopper et al.19 proposed adding a bolus of saline solution (SS) to reduce the necessary volume of CM. This was a milestone in injection systems and the use of a concomitant bolus of SS became widespread.

Another necessary adjustment made as a consequence of high flow rates has been injection pressure detection and control, in order to avoid exceeding the tolerance of the materials used in the catheters. Otherwise, catheters could rupture risking extravasation, ineffective injection or even intravascular embolism. This is determined by a pounds per square inch (psi) parameter, which refers to the force, in pounds, exerted by the injection system at any given point.

Irrespective of the technology used, all contrast injection systems have some common elements that are easy to recognise.20 All have a mechanical support, which can be floor- or ceiling-mounted, an injector head equipped with operating controls, and a control system, usually a touch screen. This screen is installed remotely in the control room of the respective modality, and constitutes a computer system that enables the design of all aspects critical to the outcome of contrast administration, such as the type of substance to be administered (CM or solution), volume, desired flow rate and phases of administration.

Technological advances have made it possible to use SS for test injections, avoiding extravasation, lowering the amount of contrast used and reducing artifacts associated with beam hardening due to high concentrations.

It is possible to adjust the variable flow rate and mix contrast and SS at any point of the injection, facilitating uniform enhancement in highly complex scans such as cardiac CT. There are multiple contrast administration phases, enabling split-bolus protocols which are useful in certain circumstances such as CT urography or with polytrauma patients to achieve combined effects of structure enhancement in a single image acquisition.

In the early days, the power injection systems were not designed to handle large volumes or today's high-turnover environments. In an attempt to reduce the time required to reload the injection systems and the possibility of contagion when using the same equipment on successive patients, modern systems incorporate automatic reloading of both SS and contrast, and the use of anti-reflux valves and disposable, single-use tubing extensions.

The incorporation of communication with the RIS-PACS system is one of the latest capabilities to be added, providing an element of safety by guaranteeing injection traceability to track any safety event, facilitating quality control in relation to the degree of enhancement obtained in the images, and allowing the replication of identical injection conditions in subsequent studies.

The same needs (high administration flows, worker protection) and advantages (reproducibility, etc.) obtained with the power injection systems in angiography and CT justify their use in other imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging or positron emission tomography with CT (PET-CT), although in both cases the characteristics of the environments and the CM (gadolinium and radiolabelled tracers) require adaptations in their design.21,22

Table 3 shows the characteristics that should be included in an advanced CM administration system for CT to guarantee appropriate and safe usage.

Characteristics recommended for contrast media injectors for computed tomography equipment.

| Required | Desirable | Optional |

|---|---|---|

| Double injection: contrast-saline solution | Multiphase injections | Mixture of contrasts and variable flows |

| Flows of at least 3–5 ml/s | Recordable protocols | Remote diagnosis and tracking |

| CM/SS volumes 150 ml | Light | PACS/RIS connection |

| Injection data records | Stand-alone power | Contrast leak detection |

| Air detection in system and shutdown | Extravasation detection | Automatic consumable use limitation |

| Excess pressure detection and shutdown | 1–7 ml/s flows in intervals of 0.5 ml | Individualised contrast optimisation |

| Automatic system shutdown | KVO | |

| Remote injection | CM/SS volumes over 150 ml | |

| Affordable single-use parts | Easy accessibility |

CM: contrast media; SS: saline solution; KVO: keep vein open.

Adapted from Friebe M. 2016.17

Enhancement is the increase in attenuation (in Hounsfield units) of a structure when comparing studies with and without intravenous contrast. This increase is directly related to the plasma and tissue concentration of iodinated contrast. It is important to know the temporal distribution of ICM so that the appropriate phase(s) of the study can be acquired, in line with the diagnostic suspicion.

DistributionThe intravascular intravenous route is the most common. Here, the ICM passes into the venous stream from the circulatory system and continues its course to the right heart chambers, pulmonary circulation and left heart chambers, before returning to the circulatory system, first through the arterial region, then to organs and tissues, and then back into the venous stream.

All commercially available ICMs share very similar pharmacokinetics. They consist of small molecules, with extracellular distribution and a low protein binding rate (1%–3%), which gives them a high capacity to diffuse into the interstitial space. Transmission is limited by vascular flow.

Following intravenous administration, the concentration of ICM in blood follows a two-step distribution pattern23:

- 1

Alpha or distribution phase: the plasma concentration of ICM peaks after injection. Subsequently, the ICM diffuses rapidly into the interstitial space of the various tissues and organs. In this first phase, the plasma concentration descends steeply until equilibrium is reached between the plasma and interstitial concentrations within minutes of injection. This distribution is not homogeneous, and depends on factors such as perfusion, permeability of the microvasculature, organ volume and tissue composition. Two components are recognised: the central, vascular and well-perfused organs (kidney, spleen, liver) with greater enhancement in the initial circulation or first passage, and the peripheral less well-perfused tissues (muscle, adipose tissue or bone) which exhibit less enhancement.

- 2

Beta or elimination phase: after reaching equilibrium between the plasma and interstitial concentrations, the ICM begins to be eliminated in a uniform manner, resulting in a lower gradient slope.

Furthermore, there are three phenomena that influence the intravenous distribution of ICM24:

- A

Dilution: as the contrast advances, it dilutes, affecting primarily the enhancement of organs more distal to the injection site.

- B

Recirculation phenomenon: the vascular system divides and gives rise to multiple simultaneous circulatory pathways, each with a different length. Some organs that enhance earlier, such as the spleen, due to its proximity to the injection site and/or greater vascularisation, contribute earlier to the passage of contrast into the venous system. The average transit time for recirculation is 15–40 s. The recirculation phenomenon can contribute to the enhancement of an organ and will depend on the duration of the injection (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.The yellow curve represents the enhancement curve of a structure over time without taking into account the phenomena of recirculation and haemodynamic disturbance. The blue curve represents the enhancement curve of a structure over time taking into account the phenomena of recirculation and haemodynamic disturbance. A. Short CM injection, the real curve (blue) is narrowed by the phenomenon of haemodynamic disturbance (pink ascending arrow); mainly due to the injection speed which accelerates the slower intrinsic flow of the peripheral venous blood compacting the duration of the contrast bolus passage. B. Long CM injection, the real curve (blue) is narrowed by the phenomenon of haemodynamic disturbance (pink ascending arrow); it reaches a higher attenuation peak achieving a more persistent enhancement over time due to the recirculation phenomenon.

- C

Haemodynamic disturbance: volume and injection rate accelerate the slower intrinsic flow of peripheral venous blood, compacting the duration of bolus passage through a structure.

These phenomena mainly affect vascular studies with a high injection rate (3–5 ml/s). In short injections (up to 15 s), peak aortic enhancement will be little affected by the contribution of recirculated CM, but prolonged injection studies will have an initial rapid enhancement, a progressive gradual increase to peak, and a gradual decrease. Both will be affected by the phenomenon of haemodynamic disturbance.

Metabolism and eliminationICM do not undergo metabolism, and in healthy subjects approximately 96% is eliminated by renal excretion via glomerular filtration, with no significant tubular reabsorption. The extrarenal route is insignificant in healthy subjects, but may reach up to 20% in patients with renal impairment through what is known as vicarious excretion—usually via the biliary tract, but also via the intestinal or transmucosal routes, and to a much lesser extent through saliva, sweat and tears. Therefore, it is not unusual to identify contrast in the gallbladder on CT studies acquired within hours of a previous administration.

The half-life of the ICM, i.e. the time in which the peak concentration obtained with the administered dose is halved, is approximately 90–120 min. In healthy individuals, 12% is eliminated within 10 min, allowing the acquisition of an elimination phase after this time. Ninety percent is eliminated in the first 24 h, although it can take weeks if there is renal impairment.

Pharmacokinetic peculiarities of iodinated contrast mediaThere are some particularities regarding the pharmacokinetics of ICMs that should be known:

- 1

The molecules do not cross the blood-brain barrier, but can diffuse into the cerebrospinal fluid.

- 2

In pregnancy, ICM cross the placental barrier and enter the bloodstream of the foetus, which can lead to the most significant adverse effect, thyroid gland dysfunction. For this reason, in countries that do not routinely screen for neonatal hypothyroidism, it is necessary to rule this out in newborns whose mothers have undergone ICM studies during pregnancy. No teratogenic effects have been demonstrated for iodinated contrasts, although ionising radiation has been shown to cause teratogenic effects.25–28

- 3

Breastfeeding: As mentioned, 90% of ICM disappears from the maternal bloodstream within 24 h. Only 1% is excreted in breast milk and less than 1% of the contrast ingested by the infant is absorbed by the intestine. Thus, it is estimated that only 0.01% of the administered ICM can reach the infant's bloodstream. This dose represents less than 1% of the dose administered in cases where an infant imaging study is necessary. Therefore, breastfeeding should not be disrupted. The only warning should be that it can change the taste of breast milk.26–30

ICM enhancement in a CT study is affected by numerous factors that depend on the patient, the CM and the equipment used.31

The most relevant aspects related to the patient include:

- A

Body weight: There is an inversely proportional relationship between the magnitude of the enhancement and body weight. The heavier the patient, the greater the volume of blood and other tissues, and thus the higher the dose of contrast required.

- B

Cardiac output: The time required to achieve the desired enhancement is inversely proportional to the cardiac output, which is a crucial factor when planning a CT study. A decrease in cardiac output slows circulation, delaying optimal enhancement at all stages. The time to arrival of the contrast bolus and the time to peak enhancement in all organs are closely related to cardiac output.

Aspects related to the CM will be discussed elsewhere in this monograph, but mainly include the CM itself, its volume and iodine concentration, the access route, the speed with which it is injected and the duration of the injection.

Two fundamental concepts will condition the levels of contrast and the way it will be administered: iodine flow and iodine load. These are essential for defining a contrast administration protocol, depending on whether it is a vascular or visceral study, respectively. The iodine flow refers to the speed with which the iodine enters the bloodstream, and is defined by the speed that the CM is injected in millilitres per second (ml/s) and the concentration of iodine in said CM, usually expressed in grams of iodine per ml (gI/ml). Multiplying both factors yields the iodine delivery rate (IDR), which is one of the factors that has the greatest impact on the quality of a vascular study. Iodine load is defined as the amount of iodine administered per body weight of the patient, and is usually expressed as grams of iodine per kilogram of body weight (gI/kg). The iodine load is calculated by multiplying the volume of CM by the iodine concentration of the CM, divided by the weight of the patient. The iodine load will be the key parameter to consider in studies that aim to achieve adequate visceral enhancement.

Finally, technical parameters (namely the kilovoltage, the duration of the study or whether spectral information is available) determine the enhancement obtained.

Methods for determining the delay of a studySeveral methods exist to determine the delay after contrast administration before a CT image is taken. This delay is an essential aspect in the exploration protocol and is determined by the objective of the study.24,31 There are three main methods, and the first two allow accurate calculation of the diagnostic delay (DD). These are explained in Fig. 6.

Bolus test technique, commonly used for vascular studies. A) Short injections, the delay is calculated as ‘Time to peak enhancement minus half the study acquisition time’. B) Long injections, the delay is calculated as ‘Time to peak enhancement minus one third of the study acquisition time’. C and D) Bolus tracking technique for short (C) and long (D) injections: the full dose of contrast bolus is injected and a sequential acquisition starts, stopping when enhancement exceeds a predetermined threshold. Then, the CT acquisition starts after an additional diagnostic delay time, set according to when the desired phase(s) has passed.

Test bolus method: This involves injecting a small test bolus (10–20 ml) of ICM prior to the diagnostic CT image with the full-dose bolus. In the topogram of the study that will be performed, we choose a level at which a single low-energy cross-section slice will be acquired, and in which a region of interest (ROI) is placed over a target organ, commonly a vascular structure. After 5–10 s, multiple sequential images are taken, recording a time-dependent enhancement intensity curve (HU) within the ROI. The test bolus and diagnostic bolus should be injected at the same rate. The time to maximum contrast enhancement of the test bolus, together with the injection duration and the acquisition duration, allow the delay to be calculated (Fig. 6A and B).

This technique is almost exclusively used for vascular studies with short injections, as explained in Fig. 6A. In vascular studies with long injections (Fig. 6B), the enhancement curve is longer and asymmetrical as it is influenced by the recirculation phenomenon, and the DD calculation must be adapted.

Bolus tracking: Similar to the test bolus method, but using the full dose of CM. The ROI is placed on a target organ and HU is recorded over time. The sequential acquisition stops after the enhancement exceeds a threshold predetermined by the operator. Then, once an additional DD time, also previously set according to the desired phase(s), has passed, the CT scan acquisition starts (Fig. 6C and D).

The bolus tracking method is more efficient as it does not require two separate injections and reduces how much contrast is required.

Its accuracy depends on the threshold value set and the DD, which depends on the organ to be studied and the purpose of the study.

Fixed delay: This option involves systematically assigning a specific delay to all patients according to the phase to be acquired. This set time is based on the known physiology of blood circulation in a specific anatomical region or on previous experience. It does not take into account the patient's cardiac output and is therefore more likely to result in studies with inadequate enhancement, increasing the risk of needing a repeat study. In addition, if the patient's cardiac output varies between two studies, they will be more difficult to compare.

ConclusionIn this article, we have reviewed various aspects of the properties, pharmacokinetics and distribution of ICM. We have also analysed the mechanism by which x-rays attenuate and discussed some of the issues affecting the intravascular use of ICM.

CRediT authorship contribution statement- 1

Research coordinators: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 2

Study concept: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Claudia Fontenla-Martínez, Luis Concepción Aramendía, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 3

Study design: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Claudia Fontenla-Martínez, Luis Concepción Aramendía, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 4

Data collection: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Claudia Fontenla-Martínez, Luis Concepción Aramendía, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Claudia Fontenla-Martínez, Luis Concepción Aramendía, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 6

Data processing: N/A.

- 7

Literature search: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Claudia Fontenla-Martínez, Luis Concepción Aramendía, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 8

Drafting of article: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Claudia Fontenla-Martínez, Luis Concepción Aramendía, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Claudia Fontenla-Martínez, Luis Concepción Aramendía, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

- 10

Approval of the final version: Jorge Cobos Alonso, Claudia Fontenla-Martínez, Luis Concepción Aramendía, Juan Matías Bernabé García, Juan José Arenas-Jiménez.

This project has not received any funding.