Supplement “Pulmonary Interstitial Pathology”

More infoSystemic autoimmune diseases comprise a complex, heterogeneous group of entities. Noteworthy among the pulmonary complications of these entities is interstitial involvement, which manifests with the same radiopathologic patterns as in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. High-resolution computed tomography is the gold-standard imaging technique; it enables us to identify and classify the disease and to determine its extent, providing useful information about the prognosis. In this group of processes, the most common pattern of presentation is nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. It is essential for radiologists to work together in collaboration with other specialists to reach the correct diagnosis and enable appropriate, integrated treatment.

Las enfermedades autoinmunes sistémicas son un grupo heterogéneo y complejo de entidades. Entre sus complicaciones pulmonares destaca la afectación intersticial, que se manifiesta con los mismos patrones radiopatológicos descritos en las neumonías intersticiales idiopáticas. La tomografía computarizada de alta resolución es la técnica de imagen de referencia, que permite identificar, clasificar y determinar la extensión de la enfermedad pulmonar, aportando datos pronósticos. En este grupo de procesos el patrón de afectación más común es el de neumonía intersticial no específica. La colaboración del radiólogo con otros especialistas resulta esencial tanto para alcanzar el diagnóstico correcto como para un manejo adecuado e integral del paciente.

Systemic autoimmune diseases (SADs) constitute a diverse group of processes whose common denominator is the presence of circulating autoantibodies capable of causing organ damage. The most significant are connective tissue diseases or disorders: rheumatoid arthritis (RA), scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM), mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Systemic vasculitis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) have also been included in the spectrum of SADs.

Pulmonary involvement is common in all of these, though with variable prevalence; the presence of interstitial lung disease (ILD) has both a prognostic and therapeutic impact. Other components of the lung (airway, alveolar space, vessels) and extrapulmonary compartments of the chest (pleura, pericardium, myocardium, chest wall muscles, oesophagus) may be involved, resulting in a wide range of manifestations.1–3

Computed tomography (CT) plays an essential role in the diagnosis and management of ILD related to SAD (SAD-ILD), which must be carried out within a multidisciplinary team.3

This article reviews the radiological manifestations of these diseases and their diagnostic approach.

Clinical contextThe clinical presentation of SAD-ILD varies widely: from asymptomatic patients to others with severe dyspnoea. The association between connective tissue disease and ILD is more common in scleroderma and idiopathic inflammatory myopathies.2 Technical advances in CT and its widespread use have boosted detection of pulmonary involvement, which can appear at any time in the natural history of the disease. Three scenarios are described: a) in patients with established SAD (most common); b) as the first manifestation of an occult connective tissue disease (in 20–30% of cases); c) associated with certain autoimmune features, but without a defined entity, the so-called interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features or (IPAF).1–4

The estimated prevalence of ILD in the different connective tissue diseases and the main extrathoracic manifestations of each disease are summarised in Table 1.5

Prevalence of ILD and extrathoracic manifestations in the main connective tissue diseases.

| Connective tissue disease | Prevalence of ILD | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| RA | Detectable on HRCT: 19–56% | Polyarticular synovitis |

| Clinically evident: 10–30% | Cutaneous rheumatoid nodules | |

| Scleroderma | Detectable: up to 75% | Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, digital ulcers, telangiectasia, skin thickening, |

| Clinically relevant: 25–45% | gastrointestinal symptoms | |

| SS | 10–30% | Dry syndrome |

| Parotid enlargement | ||

| IIM | 30%–50% | Symmetrical proximal muscle weakness, mechanic’s hands, Gottron’s sign, heliotrope rash, “shawl sign” |

| 80% in antisynthetase syndrome | ||

| Clinically relevant: 17–35% | ||

| MCTD | 20–85% | Hand oedema, synovitis, myositis, acrosclerosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| SLE | Detectable: 30–70% | Malar rash or photosensitivity, serositis, oral ulcers, alopecia |

| Clinically evident: 3–11% |

HRCT: high resolution computed tomography; IIM: idiopathic inflammatory myopathy; ILD: interstitial lung disease; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; SS: Sjögren’s syndrome.

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) may show a restrictive pattern, along with decreased diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO). They are useful for follow-up, but their sensitivity is low in the initial phases.2

The study of serum systemic autoantibodies is part of the diagnostic process of SAD and the assessment of patients with suspected idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP).1,3 Certain autoantibody profiles are characteristic of a particular disease and may suggest organ involvement. The main associations are outlined in Table 2.5,6

Autoantibodies in connective tissue diseases.

| Connective tissue disease | Autoantibody |

|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | RF |

| Anti-CCP: association with RA-ILD | |

| Scleroderma | ANA |

| Anti-centromere: association with PHT (limited disease) | |

| Anti-Scl 70 (anti-DNA topoisomerase I): association with ILD (diffuse disease) | |

| Anti-RNA polymerase I, III | |

| Sjögren’s Syndrome | ANA |

| Anti-Ro 60 (SSA), anti-Ro 52 (SSA), anti-La (SSB) | |

| Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy | ANA |

| Ab. specific to myositis: | |

| Antisynthetase ab (Jo-1, PL7, PL12, EJ, OJ) | |

| Anti-MDA5: associated with rapidly progressive ILD | |

| Anti-Mi-2 | |

| Anti-TIF1-gamma, anti-NXP2: DM associated with neoplasms | |

| Ab. associated with myositis: anti-PM-Scl, anti-Ro 52, anti-ku | |

| MCTD | ANA |

| Anti-RNP (MCTD diagnostic criteria) | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | ANA: in 95% |

| Anti-dsDNA: correlation with disease activity | |

| Anti-Ro 60, anti-Ro 52, Anti-La: cutaneous involvement | |

| Anti-Sm: most specific Ab. for SLE (present in 5–30%) | |

| Anti-RNP (in 20–50%) |

Ab: antibody; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; CCP: cyclic citrullinated peptide; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; DM: dermatomyositis; dsDNA: double-stranded DNA; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease; MDA5: melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; NXP2: nuclear matrix protein 2; PHT: pulmonary hypertension; RA-ILD: interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis; RF: rheumatoid factor; RNA: ribonucleic acid; RNP: ribonucleoproteins; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; Sm: Smith; SSA: Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen A; SSB: Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen B; TIF: transcriptional intermediary factor.

High-resolution CT (HRCT) is the reference imaging method for the diagnosis of ILD. It allows interstitial involvement to be confirmed and morphological pattern and extension to be defined.5 Its routine use in screening has only been proposed in diseases with a high prevalence of interstitial lung involvement, such as scleroderma and antisynthetase syndrome. A variable proportion of asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic patients present with mild interstitial alterations, so HRCT makes possible the identification of subclinical stages. Chest radiography is not very sensitive for detecting ILD, but it is useful for follow-up and identifying pulmonary complications. In recent years, lung ultrasound has been proposed as a method for detecting and monitoring ILD in connective tissue diseases, especially in scleroderma.2,7

Radiopathological patternsThe radiological and histological patterns of SAD-ILD overlap with those that have been described in IIP.8 In connective tissue diseases, the most common is the pattern of non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), followed by the pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). Other patterns may also appear, such as organising pneumonia (OP), lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP), and diffuse alveolar damage (DAD). Table 3 provides the relative prevalence of these patterns in the different connective tissue diseases.9–11

Relative prevalence of ILD patterns in connective tissue diseases.

| ILD pattern | Scleroderma | RA | SLE | IIM | SS | MCTD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global incidence | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| NSIP | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| UIP | + | +++ | + | + | + | + |

| OP | + | ++ | ± | +++ | ± | + |

| LIP | ± | ± | ± | ± | ++ | ± |

IIM: idiopathic inflammatory myopathy; ILD: interstitial lung disease; LIP: lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease; NSIP: non-specific interstitial pneumonia; OP: organising pneumonia; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; SS: Sjögren’s syndrome; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; +++: most common; ++: common; +: recognised but rare; ±: rare.

- -

NSIP pattern: Characterised by ground glass opacities, usually associated with bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis and mild reticulation. They predominate in the lower lobes, often with a symmetric peribronchovascular distribution. The absence of involvement of the subpleural region is typical and appears in approximately 60% of cases.12 Honeycombing is usually absent or limited and occurs in advanced stages.9,10

- -

UIP pattern: presents with reticulation, traction bronchiectasis and honeycomb cysts, peripherally distributed and predominantly basal.8–11 There may be ground glass opacity that is not widespread, coinciding with areas of reticulation. Chung et al. described three signs whose presence increases the suspicion of connective tissue disease: the anterior upper lobe sign (fibrosis is located in the anterior region of the upper lobes, with minimal involvement of the posterior regions of said lobes), the exuberant honeycombing sign (when honeycombing accounts for more than 70% of the extension of the fibrotic findings) and the straight-edge sign (sharp demarcation between lower lobe fibrosis and healthy lung in the craniocaudal axis). The last two are the most specific13 (Fig. 1).

- -

OP pattern: bilateral consolidations of peripheral or peribronchial distribution appear, more commonly in the lower lobes. A perilobular pattern (polygonal opacities limiting the secondary pulmonary lobules) and the reversed halo sign suggest the diagnosis. Other manifestations include nodular or pseudonodular lesions, ground-glass opacities, and the halo sign. Rapid response to steroid therapy is characteristic.8–11

- -

LIP pattern: this has a variable appearance. It usually presents with predominantly basal ground glass opacities and thin-walled air cysts with a peribronchovascular distribution.9,11

- -

DAD pattern: shows ground-glass opacities combined with consolidation or a “crazy-paving” pattern The distribution is symmetric and gravitational. May progress to fibrosis (usually within weeks) with reticulation and predominantly anterior and upper traction bronchiectasis.3

The role of surgical biopsy is uncertain in the presence of established SAD since it usually does not provide additional diagnostic or prognostic information. Therefore, it should be reserved for those cases with diagnostic doubts after multidisciplinary discussion.5,14 In general, radiopathological findings do not enable patterns caused by IIP to be differentiated from those associated with SAD. However, in addition to the previously mentioned signs, some features may suggest connective tissue disease, especially when they appear in an atypical context for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), such as their presentation in women under 50 years of age. These features include the combination of patterns (e.g., NSIP and OP), multi-compartmental thoracic involvement (Table 4), as well as certain histologic findings (lymphoid aggregates with germinal centres, prominent plasma cell infiltration, or dense perivascular collagen).1,3,14 (Fig. 2)

Thoracic manifestations (not ILD) in connective tissue diseases (multi-compartmental involvement).

| Manifestation | Scleroderma | RA | SLE | IIM | SS | MCTD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airway diseasea | – | +++ | ± | – | ++ | – |

| Pleural thickening/effusion | – | ++ | +++ | – | – | + |

| Alveolar haemorrhage | – | – | +++ | – | – | “ |

| Aspiration pneumonia/lung infection | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | ± | + |

| PHT | +++ | ± | + | ± | ± | ++ |

| Nodulesb | – | +++ | – | – | + | – |

| Necrobiotics | Amyloidosis | |||||

| MALT lymphoma | ||||||

| Respiratory muscle or chest wall pathology | ++ | – | ++ | ++ | “ | + |

| Oesophageal dilatation | +++ | – | – | + | ± | + |

| Cardiac/pericardial disease | + | ++ | +++ | + | – | + |

| Osteoarticular lesion in the thoracic cavity | – | +++ | – | – | – | – |

IIM: idiopathic inflammatory myopathy; ILD: interstitial lung disease; MALT: mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease; PHT: pulmonary arterial hypertension; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; SS: Sjögren’s syndrome; +++: very common; ++: common; +: uncommon; ±: rare; -: absent.

This consists of SAD of a chronic inflammatory nature, with symmetric involvement of small joints of the hands. It is the most common connective tissue disease (1% of the adult population in developed countries) and it occurs more often in women (3:1). Respiratory involvement represents one of the most common extra-articular manifestations and one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality.15 Although the pathogenesis is not completely clear, the lung appears to be the organ where the autoimmune process begins. Inhalation of tobacco, toxins, and lung infections may initiate a local inflammatory reaction and promote protein citrullination in the lungs (conversion of arginine to citrulline). This protein modification would activate the immune response, the appearance of lymphoid tissue in the bronchial wall and the formation of antibodies: rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA).16,17

RA-associated ILD (RA-ILD) is usually detected in the first five years following RA diagnosis, but in 10–20% of cases, it may precede joint manifestations.5,15–17 Its prevalence varies according to the publications, due to the fact that the studies include non-homogeneous populations and different imaging methods. With HRCT it ranges between 19 and 56%,18 although only 10–30% of patients develop clinically significant ILD.

The main risk factors for developing RA-ILD are smoking and the presence of ACPA. Other predictors include: male sex (it is four times more common in men), high RF titres, advanced age onset of RA, and severe and erosive joint disease.5,15–17

The most frequent histological-radiological type is the UIP pattern (60%), followed by the NSIP pattern (1/3) and the OP pattern (11%). This fact differentiates RA-ILD from the rest of the connective tissue diseases, in which the predominant pattern is that of NSIP. The LIP, DAD and desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) patterns are rarer.3,15,16,18 Most patients with significant clinical manifestations present with a UIP pattern.

IPF diagnostic guidelines are useful in diagnosing fibrotic patterns in patients with RA-ILD.19,20 Jacob et al. proposed two modifications to these guidelines due to the peculiarities of the UIP pattern in RA, in order to correctly diagnose the greatest number of patients. The first is to accept that fibrotic findings (honeycombing, reticulation, and traction bronchiectasis) may be preferentially located in peripheral regions of the upper and middle lung fields (Fig. 3). The second proposes eliminating the mosaic pattern of attenuation as a finding considered inconsistent with a UIP diagnosis that would lead to consideration of an alternative diagnosis. This modification is justified by the frequent involvement of the airway in RA (bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis obliterans or follicular bronchiolitis) and the consequent mosaic pattern.21

The association of RA-ILD with emphysema is well-known given the high prevalence of smokers. Emphysema has also been described in 27% of patients with RA-ILD who have never smoked. Emphysema is associated with a worse prognosis in both smokers and non-smokers.5,18,22

ILD is the second leading cause of death in RA, after cardiovascular disease.15 Although global mortality rates have decreased, mortality from RA-ILD has increased in the last 25 years.17 The radiological aspects that entail a worse prognosis are the UIP pattern and the extent of fibrosis. The UIP pattern is associated with a median survival of four years and a similar prognosis to IPF,16 while patients with a non-UIP pattern have a significantly better prognosis.17 Jacob et al. quantified fibrosis in RA-ILD with two methods: one visual and one computerised (Computed-Aided Lung Informatics for Pathology Evaluation and Rating [CALIPER]); comparing both and correlating them with the prognosis.21

There are no recommended protocols available for the detection of RA-ILD, but it has been suggested that PFTs and HRCT be performed in patients with clinical symptoms or with risk factors.17

Systemic sclerosis or sclerodermaThis is a multisystemic autoimmune disease more common in women, with two clinical forms depending on the degree of cutaneous lesion: limited (80%) and diffuse (20%); the latter with a more aggressive course, with extensive cutaneous and internal organ involvement (kidney, heart, digestive tract and lung). Histologically, it is characterised by the triad of inflammation, fibrosis with increased collagen, and vascular injury.9,11,23

ILD and pulmonary hypertension (PHT) are the main chest findings; the first predominates in diffuse forms and the second is more prevalent in limited forms. ILD occurs in the majority of patients (more than 60%) and has a variable course. PHT occurs in 20% and is usually associated with severe lung disease, although it can appear isolated.23,24

Mortality secondary to lung disease has increased in recent years due to lower mortality from nephrological causes related to better management of kidney disease.25 ILD is responsible for 40% of deaths 10 years after the onset of the disease.23

Certain factors are related to the development or progression of ILD: diffuse form of scleroderma, recent diagnosis of connective tissue disease, advanced age at diagnosis, male sex, smoking, presence of anti-Scl 70 antibodies, and gastroesophageal reflux23,24. Early diagnosis is essential to establish the prognosis and adequate treatment, so all patients with scleroderma must be evaluated from the respiratory point of view, regardless of the systemic extension of the disease.24,25.

In HRCT, almost 50% of patients present with findings at the onset of the disease.24 The NSIP pattern is the most common manifestation (77%), well ahead of the UIP pattern (8%) or OP pattern (1%), and the combination of NSIP and UIP patterns is frequent. When pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis occurs, it carries a worse prognosis.23,26

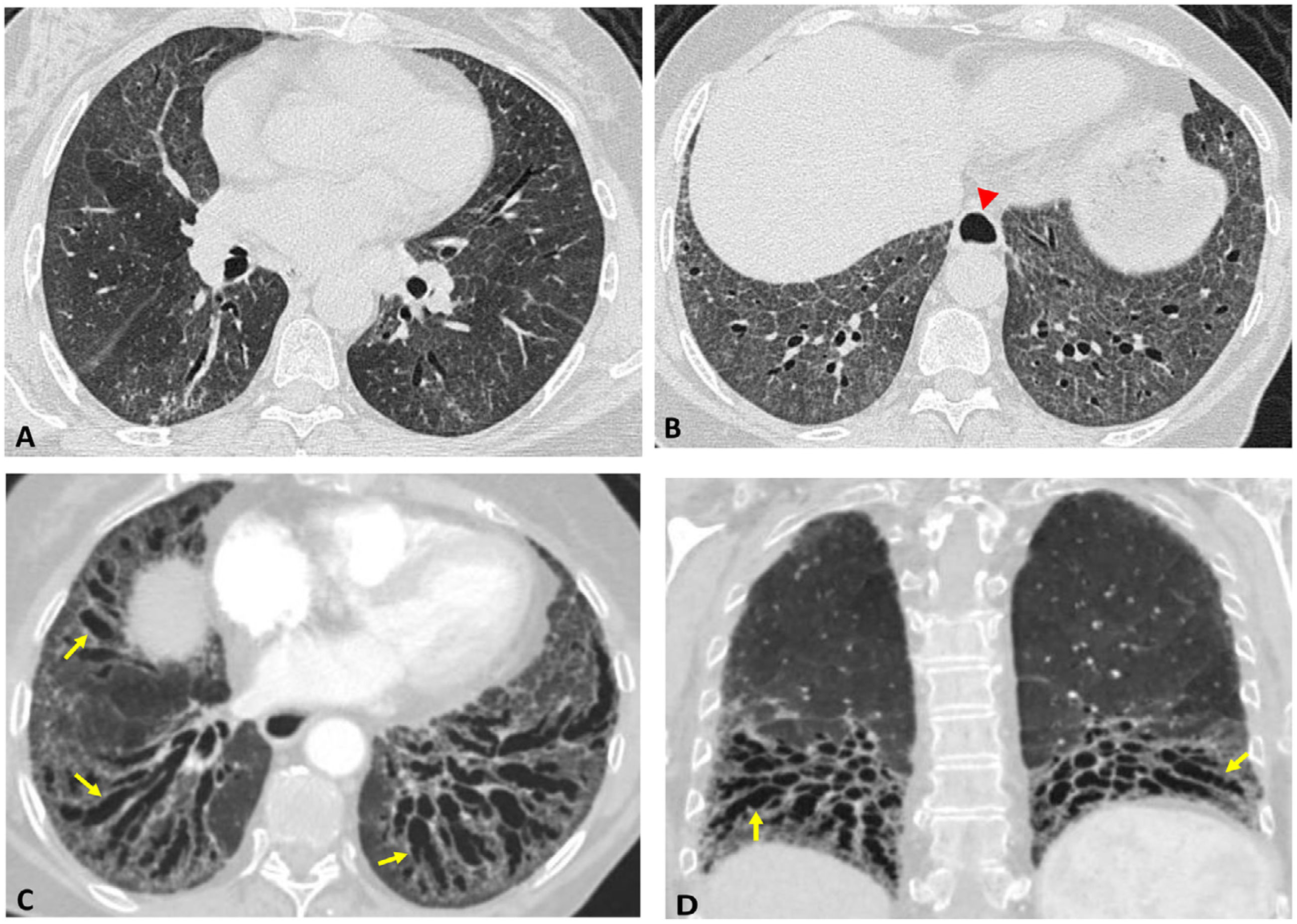

In patients with an NSIP pattern, HRCT helps to differentiate reversible inflammatory changes (pure areas of ground-glass opacities) corresponding to cellular-type NSIP from findings suggestive of irreversible fibrotic NSIP (reticulation associated with ground-glass opacities, traction bronchiectasis, distortion, loss of volume or honeycombing) (Fig. 4).23,27

Scleroderma. Initial HRCT Axial images (A and B): pattern of non-specific interstitial pneumonia, with ground glass opacities predominantly in the lower lobes associated with fine reticulation. Dilation of the distal oesophagus (arrowhead). Follow-up CT (eight years later). Reconstructions in minimum intensity projection: axial (C) and coronal (D). Prominent traction bronchiectasis (arrows) and volume loss of both lower lobes, suggestive of pulmonary fibrosis.

The “four corners” sign (predominance of interstitial involvement in the anterolateral regions of the lower lobes’ upper-middle and upper posterior fields) represents an infrequent finding. Still, it is quite specific for ILD associated with scleroderma and facilitates the differential diagnosis with IPF.9,28

Other manifestations include oesophageal dilatation, consolidation due to aspiration or pneumonia, pleural and pericardial effusion, and PHT. The latter causes dilation of the central pulmonary arteries, although a normal arterial size does not exclude it; when associated with ILD, it implies a poor prognosis.9,27

In screening for ILD in patients with scleroderma, it is recommended that HRCT be included as an initial and follow-up study. However, its periodicity has not been established (it is usually performed when there is clinical suspicion of progression).24

Combined HRCT and PFTs are the fundamental methods for evaluating lung involvement, determining prognosis, and response to treatment. The absence of interstitial disease in the initial HRCT is the best predictor of a good evolution over time. 68% of cases with ground glass opacities evolve to fibrosis,29 with the presence of fibrotic data being a predictor of poor prognosis.23 HRCT has been shown to be useful in quantifying the extent of ILD. Goh et al. establish that the extent of lung disease represents an important prognostic factor; they define “limited disease” (clearly <20% involvement) and “extensive disease” (>20%) by HRCT and fall back on PFTs (forced vital capacity greater or less than 70%) in doubtful cases.18,30 In addition to visual estimation, semi-automatic or automatic quantification systems have been developed based on histogram and texture analysis.26

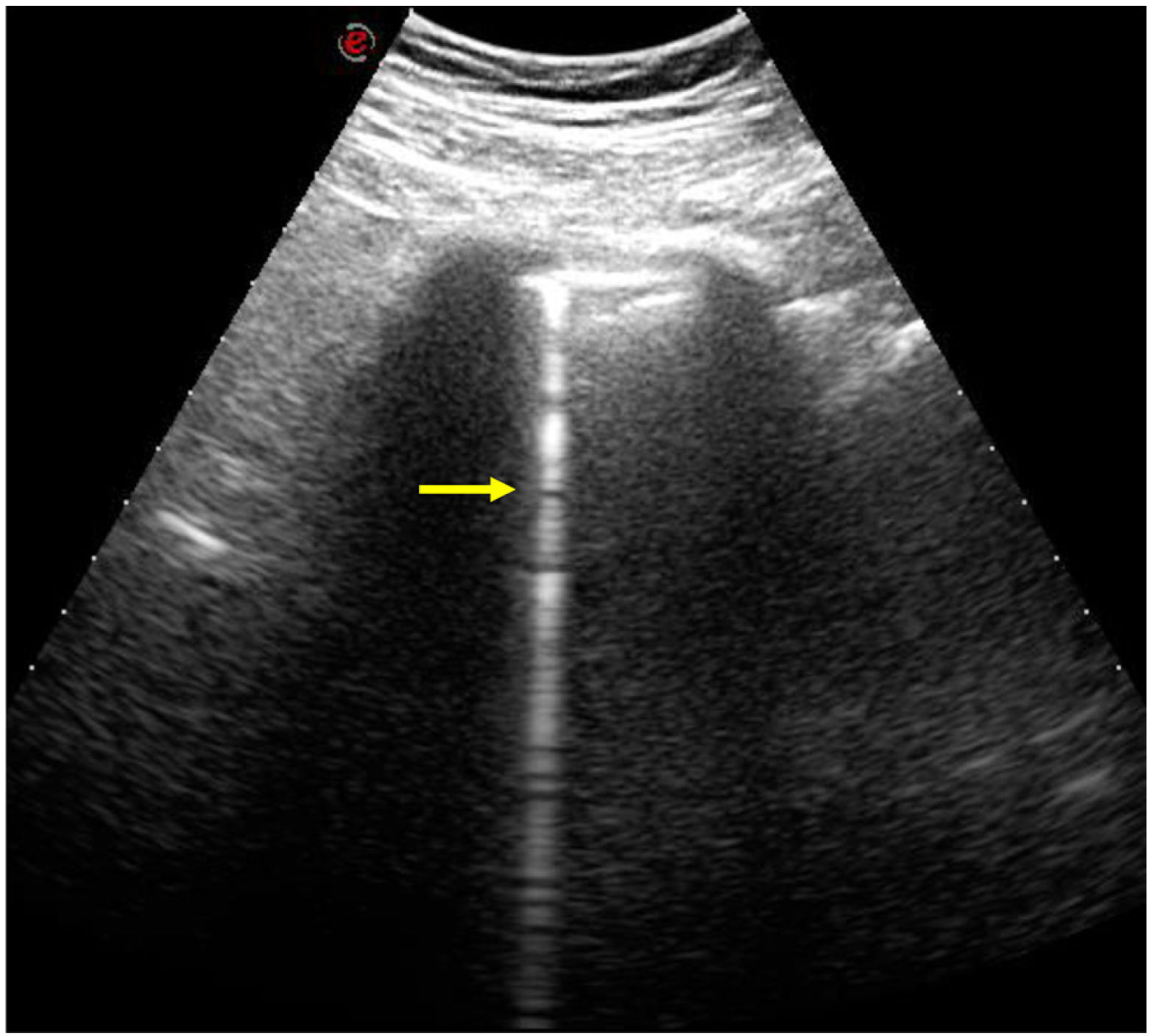

In recent years, lung ultrasound has been postulated as a useful technique for early detection and follow-up of ILD in scleroderma, which would reduce the number of CT studies in these patients.2,24 B lines are hyperechoic artefacts that extend vertically from the pleura (Fig. 5), the number of which correlates with the extension of the ILD in the HRCT.7,25 A relationship between the number of B lines and deterioration of respiratory function has recently been described, with data that would support the prognostic usefulness of pulmonary ultrasound.25 The exact role of this technique is yet to be defined.

Sjögren’s syndromeThis is characterised by an alteration in exocrine glandular function, which causes ocular and oral dryness (“sicca syndrome”), along with lymphocytic infiltration of the salivary glands. After RA it is the second most common connective tissue disease. It predominates in women (9:1) and the average age of presentation is around 50 years old.9,11 Its systemic manifestations are multiple: musculoskeletal, neurological, renal, vascular and pulmonary. There are two forms: primary (isolated) and secondary (associated with other SADs such as SLE, RA or scleroderma).10,11,31

Among the extraglandular manifestations, respiratory manifestations stand out, the most frequent in primary SS being interstitial pneumonia and airway disease (bronchial and bronchiolar). Multiple pulmonary abnormalities often coexist, complicating the interpretation of CT and histologic studies.32 In asymptomatic patients, imaging tests detect alterations in up to 65% of cases.33–35

The estimated prevalence of ILD is around 20% according to most series, making it one of the most serious complications of primary SS.36 Risk factors for its development are: male sex, active smoking, late onset of the disease and long evolution time.31.

In HRCT, ILD and signs of airway disease (centrilobular nodules, bronchiectasis or air trapping) may coexist. Although LIP is the most typical pattern of interstitial involvement (15%), the histologic pattern of NSIP is more common (45%), followed by UIP (16%)31,37. A combination of different patterns is not uncommon.28

A large proportion of ILD in SS follows an indolent course, but when there is a UIP pattern, the disease can progress and this leads to a worse prognosis.33,36 Patients with a UIP pattern associated with primary SS compared to those with UIP in IPF are characterised by: older age, predominance in women, and higher prevalence of mediastinal lymphadenopathies and bronchial wall thickening on CT.34

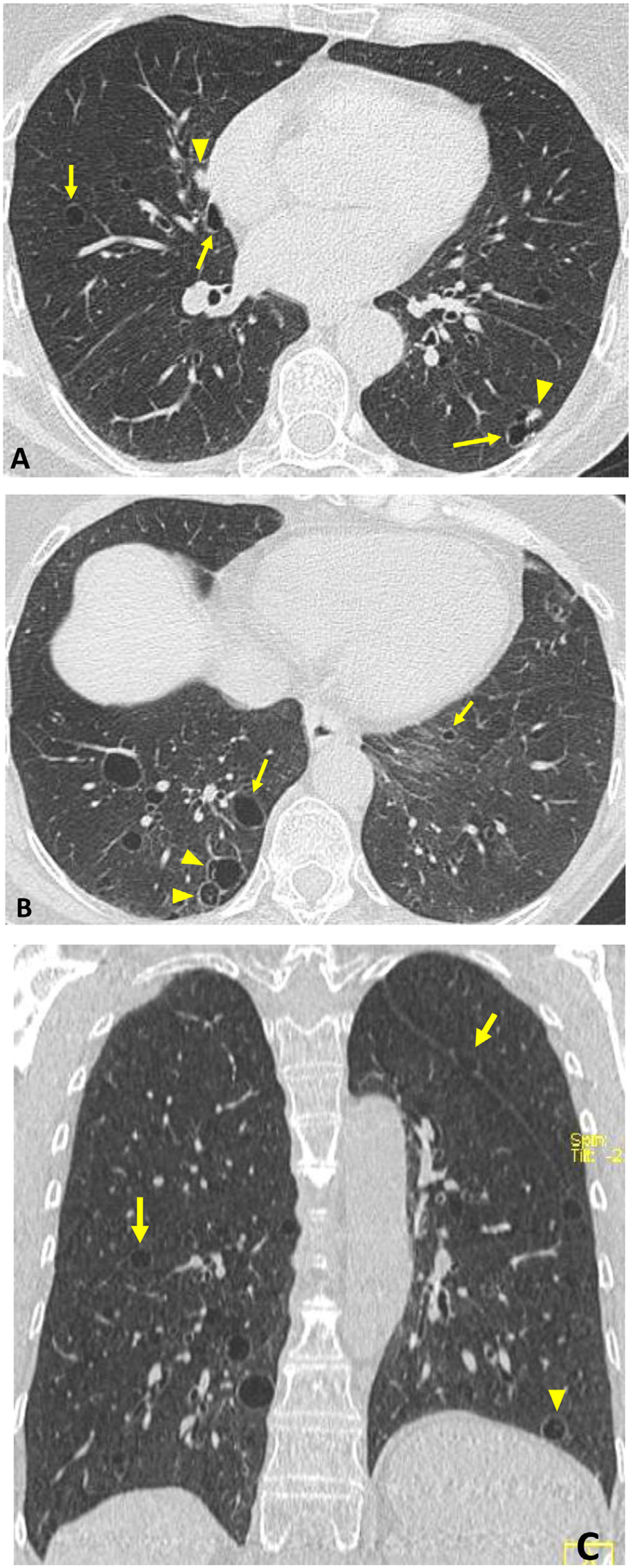

LIP is classified as rare IIP and is also considered a lymphoproliferative disorder.11,32 It often presents in SS with the only finding on HRCT being thin-walled air cysts. The association between LIP and amyloidosis is recognised, which usually manifests with cysts, ground-glass opacities, reticulation and nodules (these may be calcified) (Fig. 6).28,32,36

“Occult” Sjögren’s syndrome in an asymptomatic 54-year-old woman. Incidental finding on CT. Axial (A and B) and coronal (C) images: dispersed thin-walled pulmonary air cysts (arrows), some with incomplete thin septa (arrowheads in B and C). Several solid nodules are associated (arrowheads in A). Biopsy showed LIP and pulmonary amyloidosis.

The incidence of lymphoma in SS is greatly increased compared to the general population. Primary lung lymphoma occurs in 1-2% of patients, generally of the MALT type (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) and with a good prognosis. The presence of nodules >1 cm, masses or consolidations should alert us to this possibility.11,28,31,32,36

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathiesIIM or myositis are characterised by proximal muscle weakness, elevated muscle enzymes, myopathic changes on electromyography, and pathologic muscle biopsy. They are classified into three subgroups: polymyositis (PM), dermatomyositis (DM), and inclusion body myositis (in the latter, pulmonary involvement is rare). Some authors add amyopathic DM (with cutaneous involvement, but without myositis). The lung is the second most common extramuscular location, after the skin.38 Although PM and DM have similar manifestations, in DM there are typical skin changes such as heliotrope rash and Gottron’s papules. Antisynthetase syndrome is a clinical form of myositis characterised by the presence of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibodies and one or more of the following manifestations: ILD, PM, DM, arthritis, Raynaud’s phenomenon and mechanic’s hands.39

In IIM, two groups of autoantibodies are described: a) autoantibodies specific to myositis (they can predict the clinical form and are usually mutually exclusive), which include antisynthetase antibodies (present in 25–35% of myositis) and non-antisynthetase antibodies, and b) autoantibodies associated with myositis but not specific to IIM: they can appear in overlap syndromes or other connective tissue diseases. The anti-Jo-1 (the primary antisynthetase antibody) and anti-MDA5 antibodies are particularly relevant, as they are related to rapidly progressive ILD (over weeks or a few months), generally in the context of amyopathic DM.40

ILD is one of the most important manifestations of IIM and frequently conditions treatment and prognosis. The prevalence of clinically-significant ILD is variable (17–35%), but its overall incidence is much higher (65% or higher in some series). It precedes the diagnosis of myositis in 20% of cases.40 There are three clinical forms: acute with rapid progression, chronic with slowly progressive symptoms, and sub-clinical or asymptomatic.

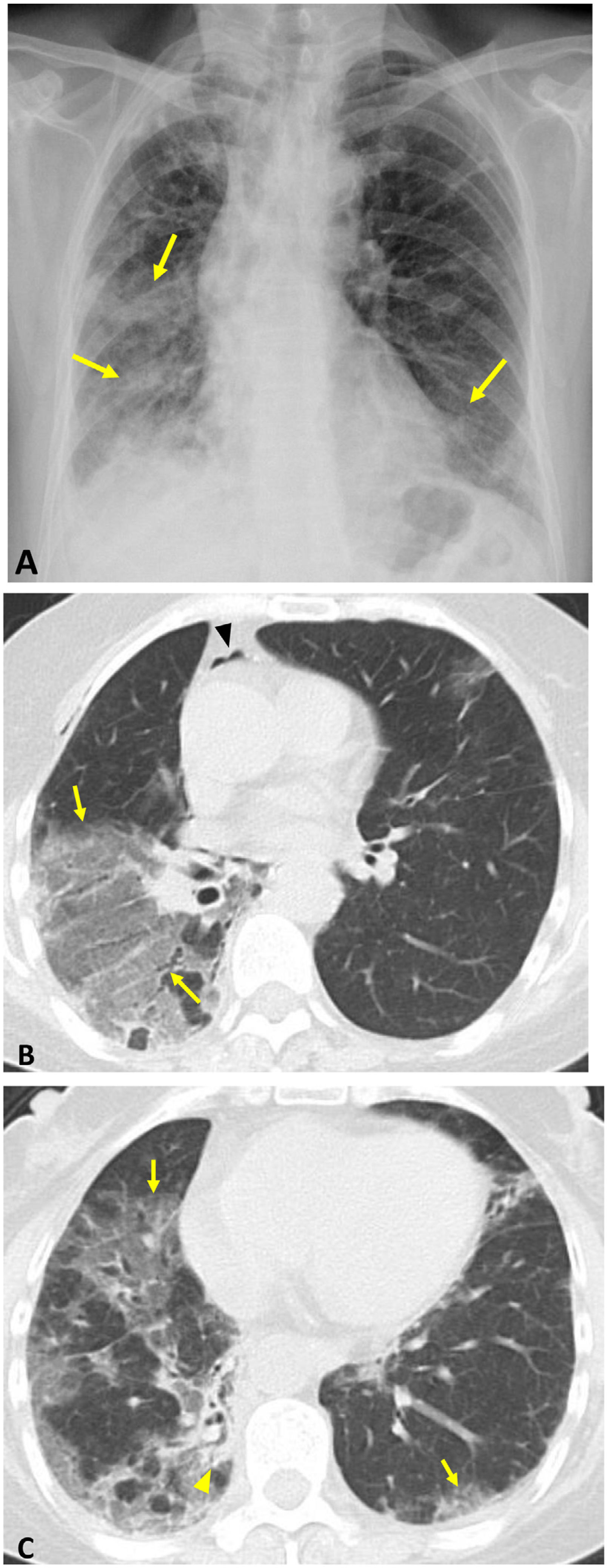

On CT, the NSIP pattern is the most common (65% in the series by Cottin et al.),41 but OP and the combination of NSIP-OP also appear, with the UIP pattern being uncommon (Fig. 7). Rapidly progressive ILD in patients with DM and anti-MDA5 antibodies manifests with an OP and DAD pattern (consolidations and ground glass opacities, with or without signs of fibrosis); pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax are associated with higher mortality.18 (Fig. 8).

Polymyositis in a 53-year-old man. Axial (A) and coronal (B) HRCT images reveal a pattern of non-specific interstitial pneumonia: ground-glass opacities predominant in both lower lobes with symmetric distribution (arrows), mild reticulation, and absence of involvement in the subpleural region (arrowheads at A).

A 57-year-old woman with rapidly progressive ILD associated with anti-MDA5 antibodies. Chest radiograph (A): bilateral consolidations with right predominance (arrows). Axial CT images (B and C): extensive ground-glass opacities with a marked predominance in the right lung (arrows) and a small focus of consolidation (arrowhead in C). Pneumomediastinum (arrowhead in B) secondary to bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy.

MCTD is a defined clinical entity that has characteristics common to SLE, scleroderma, SS or myositis (for which reason it is called an overlap syndrome), along with antibodies to ribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP). It predominates in young women (9:1). Clinical diagnosis is based on the presence of Raynaud’s phenomenon, oedema in the hands and some of the signs of the aforementioned diseases, such as myositis, arthritis, oesophageal dysmotility, leukocytopenia, serositis, ILD and PHT.6

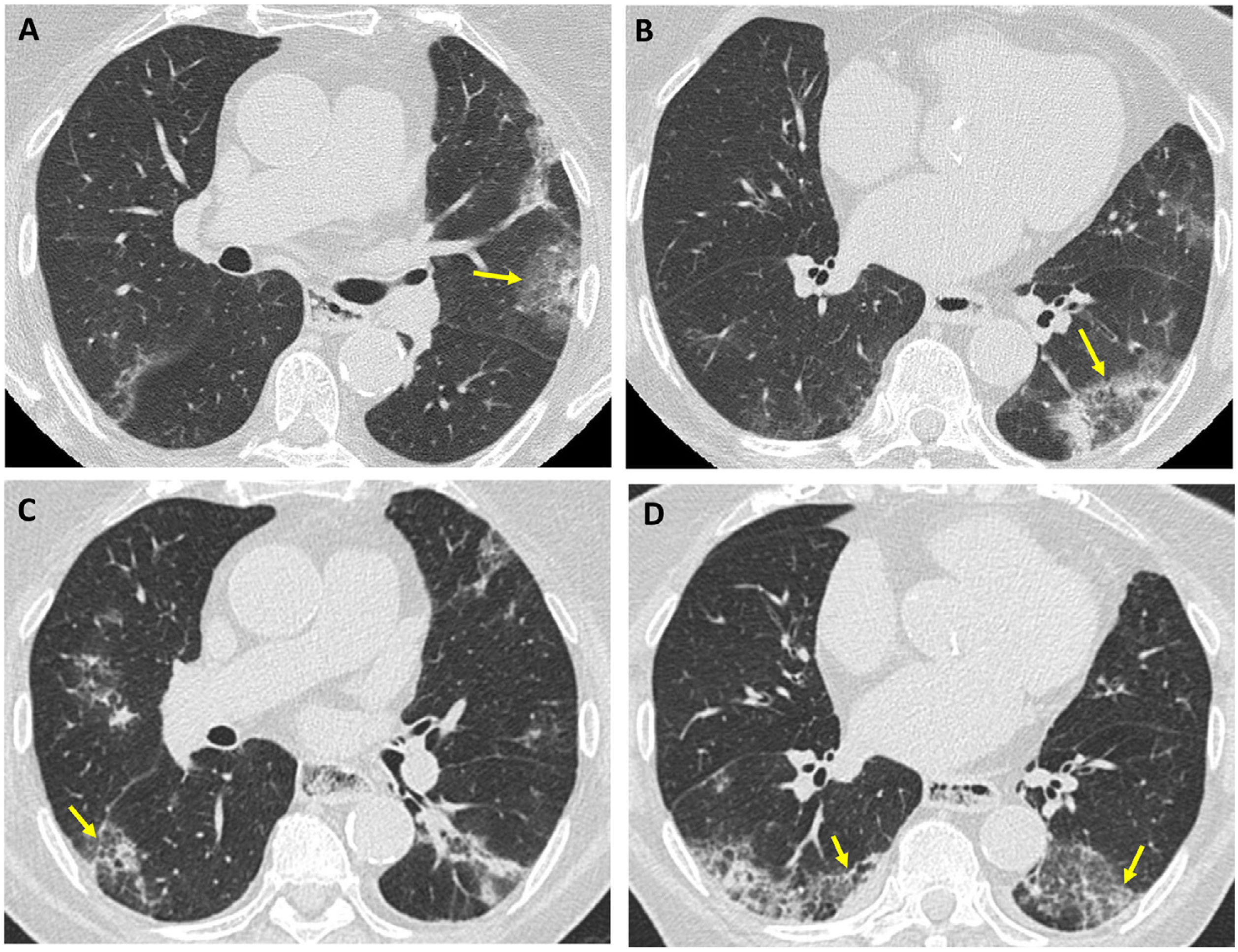

Respiratory manifestations appear in up to 80% of cases. The anti-Ro52 antibody is a marker of lung involvement. Although patients are often asymptomatic, CT shows findings in more than 50%, with ILD being the most common. Bodolay et al. found interstitial lung disease in 66% of cases.42 The predominant radiopathological pattern is NSIP, followed by UIP; LIP and OP patterns are uncommon (Fig. 9). The presence of PHT, in 10–45% of patients affected by MCTD, implies a poor prognosis.11,43,44

A 62-year-old woman with mixed connective tissue disease and a combined NSIP-OP pattern. Axial CT images (A and B): bilateral peripheral consolidations; halo sign in the left upper lobe (arrow in A) and reversed halo sign in the left lower lobe (arrow in B). Follow-up CT (C and D): ground-glass opacities predominate in both lower lobes, associated with reticulation and bronchiolectasis (arrows in C and D).

This is a chronic relapsing-remitting multi-organ disease, which has a wide variety of clinical manifestations and is associated with different autoantibodies (the majority of patients are positive for antinuclear antibodies [ANA]). It predominates in women (9:1) of reproductive age. Respiratory tract involvement occurs in 50–70% of cases and in 4–5% it is the first manifestation of the disease.45 The spectrum of possible alterations involves multiple thoracic structures, with ILD being one of the least common (Table 5).

Thoracic changes in systemic lupus erythematosus.

| Pulmonary parenchyma | Acute: |

|---|---|

| Lupus pneumonitis (1–8%) | |

| Acute alveolar haemorrhage (rare) | |

| Lung infection in 50% | |

| Chronic: ILD | |

| Pleura (the most common) | Pleuritis |

| 40–60% | Pleural effusion |

| Airway | Upper: laryngeal involvement |

| Bronchiolitis | |

| Bronchiectasis (rare) | |

| Pulmonary vessels | Pulmonary thromboembolism (10%) |

| Acute reversible hypoxemia syndrome | |

| PHT (rare) | |

| Respiratory muscles | Shrinking lung syndrome (rare) |

ILD: interstitial lung disease, PHT: pulmonary hypertension.

The severity of respiratory complications varies widely from subclinical to life-threatening forms.46 Respiratory manifestations that occur acutely are usually associated with the general activity of the disease, while chronic manifestations can progress independently.45 In the initial evaluation of pulmonary lesions, infection must be ruled out, since bacterial pneumonia is a very common complication and one of the main causes of death.47

Acute lupus pneumonitis is a feared but rare complication (1-8%) which presents with fever, cough, chest pain, haemoptysis and, in severe forms, acute respiratory failure. It usually occurs in the context of a systemic outbreak (nephritis, serositis, arthritis) and is associated with anti-Ro antibodies.45 Histologically, it is characterised by diffuse alveolar damage, which may be accompanied by capillaritis and alveolar haemorrhage.10,45 The CT shows bilateral consolidations with basal predominance; CT angiography makes it possible to exclude pulmonary embolism. In half of cases there is pleural effusion. Bronchoalveolar lavage helps differentiate lupus pneumonitis from infection and haemorrhage.47 It has a poor prognosis, with high mortality (40–50%) and a significant percentage develop chronic interstitial pneumonia.45

Chronic ILD occurs less frequently than in other connective tissue diseases, although its prevalence (6-24%) is probably underestimated.45 The most common radiopathological pattern is NSIP, although UIP, LIP and OP patterns also appear. Brady et al. describe signs of fibrosis that do not conform to the classic patterns of UIP or fibrotic NSIP in 44% of their patients.48 Among the risk factors for developing ILD, the following stand out: history of acute lupus pneumonitis, long-term evolution of SLE, Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, pathological capillaroscopy, and anti-RNP antibodies. The prognosis of fibrosing ILDs in SLE is better than those associated with IPF or RA.45

ANCA-associated vasculitisVasculitides constitute a heterogeneous group of diseases characterised by necrotising leukocyte inflammation of the walls of blood vessels. Pulmonary involvement is more common in the subgroup of ANCA-associated vasculitis, which have a predilection for small vessels and include three syndromes: microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (previously called Wegener’s disease), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome).49,50 (Table 6)

Characteristics of ANCA-associated vasculitis.

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Microscopic polyangiitis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | Necrotising granulomatous inflammation | Necrotising vasculitis | Non-granulomatous vasculitis/capillaritis |

| Extravascular granulomas | |||

| Eosinophilic infiltrates | |||

| ANCA pattern | PR3-ANCA (90%) | MPO-ANCA (40–70%) | MPO-ANCA (50–75%) |

| Clinical signs | Destructive rhinitis, otitis | Asthma (95%) | Glomerulonephritis (90%) |

| Glomerulonephritis (50–80%) | Nasal polyposis | Arthralgias/myalgias | |

| Airway stenosis | Cardiac involvement | Cutaneous involvement | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Peripheral neuropathy | ||

| Cutaneous rash | |||

| Thoracic findings (CT) | Nodules/masses (90%), frequent cavitation | Transient consolidation/ground-glass opacities | Consolidation/ground-glass opacities |

| Consolidation/ground-glass opacities | Septal thickening | Pulmonary fibrosis | |

| Pleural effusion (50%) |

ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; PR3-ANCA: anti-proteinase 3 ANCA (c-ANCA: ANCA with cytoplasmic pattern); MPO-ANCA: ANCA against myeloperoxidase (p-ANCA: ANCA with perinuclear pattern).

The association between ANCA-associated vasculitis and ILD is increasingly recognised, with microscopic polyangiitis with anti-myeloperoxidase (anti-MPO) ANCA being the most closely related to interstitial involvement (up to 45%).49 In patients with an initial diagnosis of IPF, conversion to positive ANCA has been described in approximately 10% of cases, which has led to the inclusion of ANCA antibody determinations in patients with interstitial lung disease/pulmonary fibrosis.50

The pathogenesis of ILD associated with ANCA-associated vasculitis is poorly understood, but several mechanisms have been suggested, including repeated episodes of alveolar haemorrhage and MPO-ANCA autoantibodies per se. It has also been postulated that IPF could induce the development of ANCA and vasculitis.51

In addition to non-specific respiratory symptoms such as dyspnoea and cough, other symptoms related to vasculitis may occur: haemoptysis, arthralgia, fever, weight loss, or haematuria.

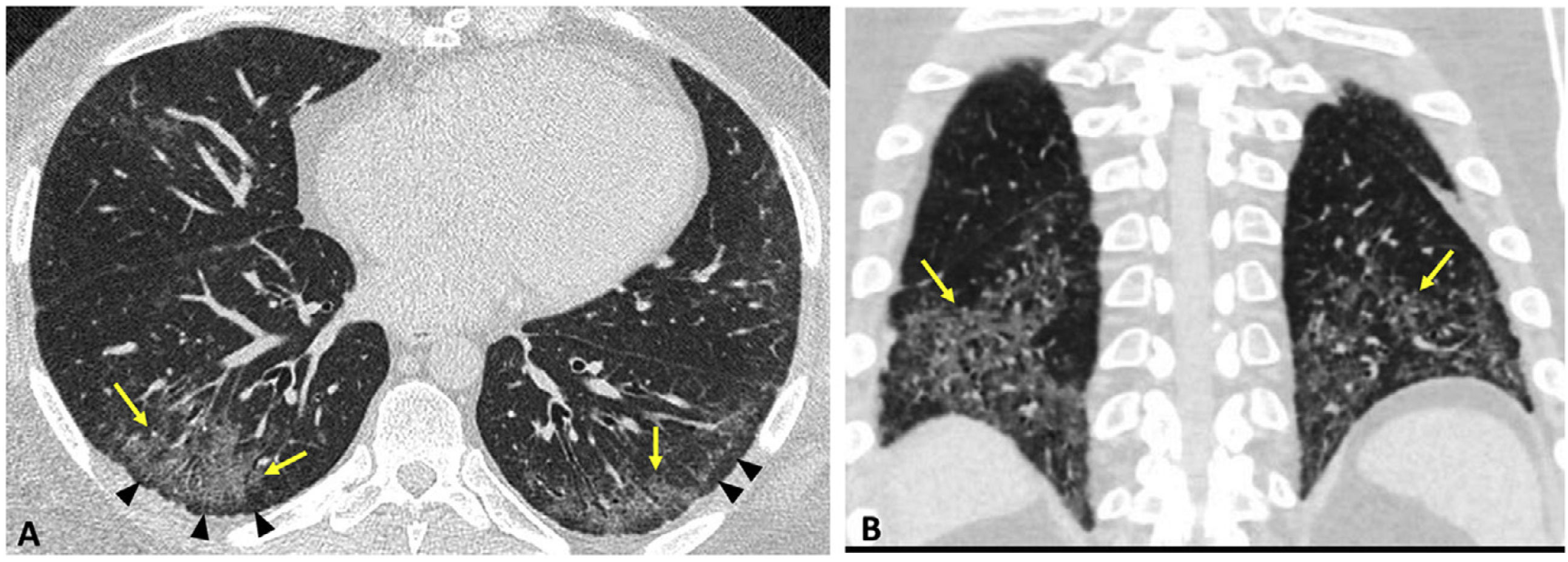

In patients with MPA, a prevalence of interstitial disease detected with CT has been estimated at 66%. The most common findings in ILD associated with ANCA-associated vasculitis include ground-glass opacities, reticulation, septal thickening, consolidation, and honeycombing. Its distribution is usually symmetrical, with peripheral predominance in the lower lobes. The most common pattern is that of UIP, followed by NSIP; DIP may also occur. In a significant percentage of cases, CT reveals fibrotic interstitial alterations that cannot be framed in a defined pattern.50 Airway involvement (bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis) is also described.49 (Fig. 10)

Microscopic polyangiitis (MPO-ANCA) with usual interstitial pneumonia pattern. Axial CT (A and B) and coronal reconstruction in minimum intensity projection (C). Reticulation associated with ground-glass opacities (arrows), traction bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis (arrowheads in B), and small areas of honeycombing (arrowhead in C). Findings with peripheral and basal predominance.

The overall survival of ANCA-associated vasculitis has increased in recent years due to the standardisation of immunosuppressive therapy. Still, the presence of ILD, particularly the UIP pattern, has an adverse prognostic impact.49

Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF)This term designates cases of IIP (identified on HRCT or by histologic study) with features suggestive, but not definitive, of connective tissue disease (in which other aetiologies have been excluded). Its classification criteria involve three domains: clinical, serological and morphological (Table 7). Within the morphological domain, certain HRCT patterns exist: NSIP, OP, combined NSIP-OP and LIP, and findings in other thoracic structures (multi-compartmental involvement). In a patient with interstitial lung disease, the UIP pattern does not increase the probability of underlying connective tissue disease, so it is not considered an IPAF criterion.4 The IPAF concept reflects the overlap between IPF and SAD-ILD and the requirement for multidisciplinary management of this disease.52

IPAF qualifying criteria.a

| Clinical domain | Serological domain | Morphological domain |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanic’s hands | ANA ≥ 1:320 diffuse or speckled pattern ANA nucleolar or centromere pattern (at any titre) | HRCT pattern: NSIP, OP, NSIP-OP, LIP |

| Distal ulcer on fingers | RF ≥ normal limit × 2 | Biopsy: NSIP, OP, NSIP-OP, LIP, lymphoid aggregates with germinal centres, diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration |

| Arthritis or morning stiffness >60 min | Anti-CCP | Multi-compartmental involvement (in addition to ILD): pleura, pericardium, airway, pulmonary vasculature |

| Palmar telangiectasias | Anti-dsDNA | |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Anti-Ro (SSA) | |

| Gottron’s sign (rash on extensor surface of fingers) | Anti-La (SSB) | |

| Digital oedema | Anti-RNP | |

| Anti-Sm | ||

| Anti-Scl-70 | ||

| Antisynthetase Ab. | ||

| Anti-PM-Scl | ||

| Anti-MDA5 |

Ab: antibody; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; CCP: cyclic citrullinated peptide; DAD: diffuse alveolar damage; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; dsDNA: double-stranded DNA; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; ILD: interstitial lung disease; IPAF: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features; LIP: lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; MDA5: melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; NSIP: non-specific interstitial pneumonia; OP: organising pneumonia; RF: rheumatoid factor; RNP: ribonucleoproteins; Sm: Smith; SSA: Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen A; SSB: Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen B; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia.

Given the significant variability of manifestations of SAD-ILD and the prognostic impact of pulmonary involvement, the integration of clinical, serological and radiological findings into a multidisciplinary discussion (pulmonologist, rheumatologist, radiologist, immunologist and occasionally pathologist) is crucial to achieving an early and precise diagnosis that enables adequate global management to be established.2,5

The clinical course of ILD is variable and unpredictable. In the evolution of these patients, acute exacerbations may occur, as in IPF. They are defined as respiratory deterioration in less than a month associated with new lesions on HRCT (generally ground-glass opacities) in the absence of infection or pulmonary oedema. This situation is more common in RA-ILD than in other SADs and is associated with high mortality.28

Acute respiratory worsening in a patient with SAD undergoing treatment can also be due to two frequent complications:

- -

Drug toxicity. Multiple drugs are used in SAD-ILD (Table 8). Specific treatment should be individualised based on the type of autoimmune disease, its clinical course, and the pattern and severity of ILD. The diagnosis of pulmonary toxicity is usually one of exclusion; the temporal relationship between the start of treatment and the appearance of symptoms and radiological findings must be established. The most common patterns of involvement are hypersensitivity pneumonitis, eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary oedema, and DAD. Methotrexate (first-line drug in RA) can cause acute pneumonitis in the first year of treatment due to a hypersensitivity mechanism. Although rare, this complication has a high mortality rate.5,15,28

Table 8.Drugs most commonly used in the treatment of SAD and SAD-ILD.

Immunosuppressants DMARD Corticosteroids Conventional synthetic cs-DMARD Biologic b-DMARD Targeted synthetic ts-DMARD Cyclophosphamide Glucocorticoids Mycophenolate Methotrexate Anti-TNF Tofacitinib Azathioprine Leflunomide Rituximab Baricitinib Cyclosporine Hydroxychloroquine Abatacept Tacrolimus Sulfasalazine Tocilizumab Anti-TNF: tumour necrosis factor inhibitors; DMARD: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; ILD: interstitial lung disease; SAD: systemic autoimmune disease.

- -

The risk of pulmonary infection is increased by immunosuppressive treatments and the immune alterations typical of systemic disease. The germs involved include bacteria, viruses, fungi (Pneumocystis jiroveci, Aspergillus) and mycobacteria (tuberculous and non-tuberculous). Before starting anti-TNF therapy (tumour necrosis factor inhibitors), the presence of latent tuberculosis or radiological findings of previous tuberculosis should be investigated (due to a high risk of transformation into an active infection).5 Some drugs are associated with specific infections. For example, pneumonia P. jiroveci is more common in treatment with methotrexate, rituximab and corticosteroids.

SAD-ILD can show a progressive phenotype, characterised by the worsening quality of life with decreased forced vital capacity and DLCO and greater extension of fibrotic lesions on HRCT. This behaviour, similar to IPF, is generically called “progressive pulmonary fibrosis” and has a negative prognostic impact with increased mortality.53 Several recent clinical trials have shown that antifibrotic treatment (nintedanib, pirfenidone) benefits progressive fibrosing ILD associated with SAD. The role these drugs play and their joint use with immunosuppressive treatment is yet to be determined.5

ConclusionsThe radiological-histological pattern of NSIP is the most common in SAD-ILD, except for RA and ANCA-associated vasculitis, in which the UIP pattern predominates. In a significant minority of patients, pulmonary involvement is the initial form of systemic disease; the presence of an NSIP pattern on HRCT along with multi-compartmental thoracic involvement increases diagnostic suspicion. The thoracic radiologist must be aware of each disease’s broad spectrum of manifestations.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: SHM, MJOS and PCSR.

- 2

Study concept:SHM, MJOS and PCSR.

- 3

Study design:SHM, MJOS and PCSR.

- 4

Data acquisition: SHM, MJOS, PCSR, JAJH and CV.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: N/A.

- 6

Statistical processing: N/A.

- 7

Literature search: SHM, MJOS, PCSR and CV.

- 8

Drafting of the article: SHM, MJOS, PCSR and JAJH.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: SHM, MJOS, PCSR, JAJH and CV.

- 10

Approval of the final version: SHM, MJOS and PCSR.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.