Supplement “Pulmonary Interstitial Pathology”

More infoThe term inhalational lung disease comprises a group of entities that develop secondary to the active aspiration of particles. Most are occupational lung diseases. Inhalational lung diseases are classified as occupational diseases (pneumoconiosis, chemical pneumonitis), hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and electronic-cigarette-associated lung diseases. The radiologic findings often consist of nonspecific interstitial patterns that can be difficult to interpret. Therefore, radiologists’ experience and multidisciplinary teamwork are key to ensure correct evaluation. The role of the radiologist is fundamental in preventive measures as well as in diagnosis and management, having an important impact on patients’ overall health. It is crucial to take into account patients’ possible exposure to particles both at work and at home.

Las enfermedades inhalatorias son un grupo de entidades secundarias a la aspiración activa de partículas. La mayoría se produce en el ámbito laboral. Se clasifican en enfermedades ocupacionales (neumoconiosis, neumonitis química), neumonitis por hipersensibilidad y enfermedad pulmonar asociada al uso de cigarrillos electrónicos. En muchas ocasiones los hallazgos radiológicos son patrones intersticiales inespecíficos de difícil interpretación. Por lo tanto, es clave una evaluación global correctamente integrada en los equipos multidisciplinares, donde la radiología realizada por profesionales con experiencia desempeña un papel fundamental tanto en el diagnóstico y el manejo, como en las medidas de prevención, con repercusión importante sobre la salud global de los pacientes. Es fundamental tener en cuenta las posibles exposiciones tanto laborales como domésticas a las que puedan estar expuestos los pacientes.

Inhalational lung diseases are caused by the active aspiration, through the nose or mouth, of particles of various sizes contained in the inspired air. Generally, particles with diameters greater than five μm are deposited in the bronchial tree and are expelled by the mucociliary system; smaller ones reach the alveolar space, from where they are incorporated into the lung interstitium, are phagocytised by the macrophages and inflammation appears.1

The evolution or severity of the disease will depend on individual susceptibility, particle solubility and size, concentration in the air, duration of exposure and their fibrogenic properties.

Although most of these exposures occur in the workplace, they can also occur in domestic and recreational settings.

Imaging tests and a thorough medical history play a vital role in diagnosing inhalational diseases. Despite advances in imaging, a large proportion of the findings seen in these diseases are non-specific, and the differential diagnosis about the other interstitial disorders is complex.2 A multidisciplinary approach involving experienced radiologists is key to diagnosing and managing these entities.3,4 These multidisciplinary teams favour early preventive measures, with an impact on global health and with a significant economic impact.5

In this paper, we review the different types of inhalational diseases: 1) occupational diseases (including pneumoconioses and chemical pneumonitis secondary to inhalation of irritant gases); 2) hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) (which, although in many cases is related to occupational exposures, may also be caused by domestic exposures), and 3) e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury (a recently described entity).

Occupational diseasesMultiple lung diseases occur secondary to exposure to inorganic dust, biological agents and toxic gases in the workplace. The most common occupational lung diseases include occupational asthma, HP, pneumoconiosis, and chemical pneumonitis due to inhalation of toxic gases and tumours.

After accidents, lung pathology is the most frequently diagnosed occupational disease6 and within them, pneumoconioses secondary to inhalation of inorganic dust are the most common occupational lung diseases. The long latency period is characteristic, with years or even decades after exposure until the onset of symptoms or radiological changes.

PneumoconiosisPneumoconioses are a group of diseases caused by inhalation and deposition of inorganic dust in the lungs and reactions due to its presence. Pneumoconioses can be subdivided into fibrogenic (silica, charcoal, talc, asbestos), benign or inert (iron, tin, barium), granulomatous (beryllium), and giant cell pneumonia associated with the inhalation of hard metals (cobalt).2,3

Pneumoconiosis is diagnosed based on employment history, chest radiograph, and pulmonary function tests.

Chest radiograph is the initial imaging test and the technique used in the periodic preventive controls that must be carried out on all exposed workers. However, it is a technique with low sensitivity and specificity. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) has higher sensitivity and specificity and better characterises the pattern of parenchymal involvement, airway disease, and pleural abnormalities.7–10

Despite these advantages, CT is not generally used as the primary detection modality for pneumoconiosis, due to its higher cost, lower accessibility, and higher radiation dose compared to chest radiography. CT is commonly used as a secondary detection modality in symptomatic workers or when a chest radiograph is ambiguous.11–13

The medical-legal assessment in Spain is based primarily on radiological criteria and not on functional limitation. Spanish legislation requires periodic posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs to be performed in exposed workers and with a radiological report according to the International Labour Organization (ILO) classification.14

This classification codifies radiographic abnormalities of pneumoconioses 15 in a simple and reproducible manner.16 It was originally developed for epidemiological purposes, but is now used in periodic examinations of exposed workers. It does not define pathological entities or assess work disabilities. It does not include legal definitions of pneumoconiosis, nor work or financial compensation. There are no pathognomonic radiological findings of pneumoconiosis.17

The ILO classification is divided into five sections:

- 1.

Technical quality of the radiograph: 1: good; 2: acceptable; 3: poor quality, and 4: unacceptable.

- 2.

Parenchymal abnormalities: taking into account size, profusion, shape and location (Fig. 1).

- -

Small opacities: described according to their profusion, affected lung fields, shape, and size.

- -

Large opacities: defined as opacities with a diameter greater than 10mm. There are three categories: A (from 10 to 50mm), B (between 50mm and the upper right field of the lung) and C (when they measure more than the upper right field).

- -

- 3.

Pleural abnormalities.

- 4.

Symbols: describe additional coded findings (for example "aa" indicates aortic atherosclerosis or "bu" indicates the presence of bullae).

- 5.

Free comments, not included in the previous reading.

Systems similar to the ILO classification have been proposed for CT findings in occupational diseases, such as the International Classification of HRCT for Occupational and Environmental Respiratory Diseases (ICOERD).9,10,14,18

SilicosisSilicosis is a fibrotic lung disease caused by the inhalation of crystalline silica (SiO2). Generally, exposure to silica dust for 10–20 years is required for the appearance of radiological changes.

Although its incidence has decreased, it continues to be the most common pneumoconiosis. In addition, new materials have appeared, such as artificial quartz (composed of 90% silica), which has increased its incidence in certain areas.

There are three forms of presentation: acute, chronic, and accelerated or rapidly progressive. The most common form is chronic silicosis, which develops after years of exposure to relatively low dust levels. The classic radiological manifestation of chronic silicosis on chest radiograph is the presence of a diffuse and bilateral micronodular pattern, with greater involvement of the upper lobes and posterior areas of the lung. In general, the nodules are rounded and relatively well defined, and can calcify in 10–20% of cases (Fig. 2).

Simple chronic silicosis. (a) Posteroanterior chest radiograph revealing a bilateral and diffuse micronodular pattern with nodules with well-defined borders with greater profusion in the upper fields. (b) HRCT with centrilobular and subpleural nodules. (c) CT with coronal reconstruction and maximum intensity projection, showing the characteristic predominance of nodules in the upper lobes.

It is known as simple silicosis when the nodules have a diameter of 1−10mm. Complicated silicosis exists when there are opacities with a diameter greater than 10mm. These clusters, termed progressive massive fibrosis (PMF) masses, are formed by the confluence of silicotic nodules. They are usually located in the middle and upper part of the lung bilaterally (Fig. 3), although on occasion, they can be found in the lower zones and even be unilateral. PMFs tend to migrate towards the pulmonary hila and typically have a convex outer edge with well-defined margins, giving them a morphology described as "angel's wings" (Fig. 4a). The presence of hilar and mediastinal adenopathies is common, which may be calcified, with a characteristic "eggshell" morphology (Figs. 4a and b); calcified adenopathies can even present in extrathoracic locations.

Complicated silicosis. (a) Posteroanterior chest radiograph: large perihilar PMF masses with volume loss in the upper lobes, with "angel's wings" morphology (white arrows). Mediastinal and hilar adenopathies with "eggshell" calcification. (b) HRCT: calcifications in the PMF masses and lymph nodes. (c) HRCT: paracicatricial emphysema left by the nodules as they migrate to the perihilar areas (black arrows).

The characteristic findings of silicosis on HRCT consist of small nodules with well-defined contours that may become calcified, with a tendency to be located in the upper and posterior lung fields, with a perilymphatic distribution and in a centrilobular and subpleural location. The confluence of subpleural nodules gives rise to a pseudoplaque morphology. PMF masses have a soft tissue density that may have associated calcifications or less dense necrotic areas in their interior and distortion of the adjacent bronchovascular architecture, with areas of peripheral paracicatricial emphysema between the fibrotic masses and the pleural surface (Figs. 4b and c).

A slowly progressive fibrosing interstitial pneumonia can appear in 10% of patients with long-standing silicosis, with a typical pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia, the so-called dust-related pulmonary fibrosis.19,20 In patients with complicated silicosis there may be pleural disease characterised by thickening and effusion.21

The second form of presentation is acute silicosis or silicoproteinosis. It is a rare manifestation of the disease, with an acute and progressive clinical picture that develops months after exposure to high concentrations of silica for short periods.22 It frequently occurs in operators who work with sandblasters.23

Similar to pulmonary oedema or alveolar proteinosis, bilateral perihilar consolidations may be seen on radiographs. HRCT shows a diffuse pattern in ground glass or airspace consolidations without the presence of a micronodularpattern.24,25

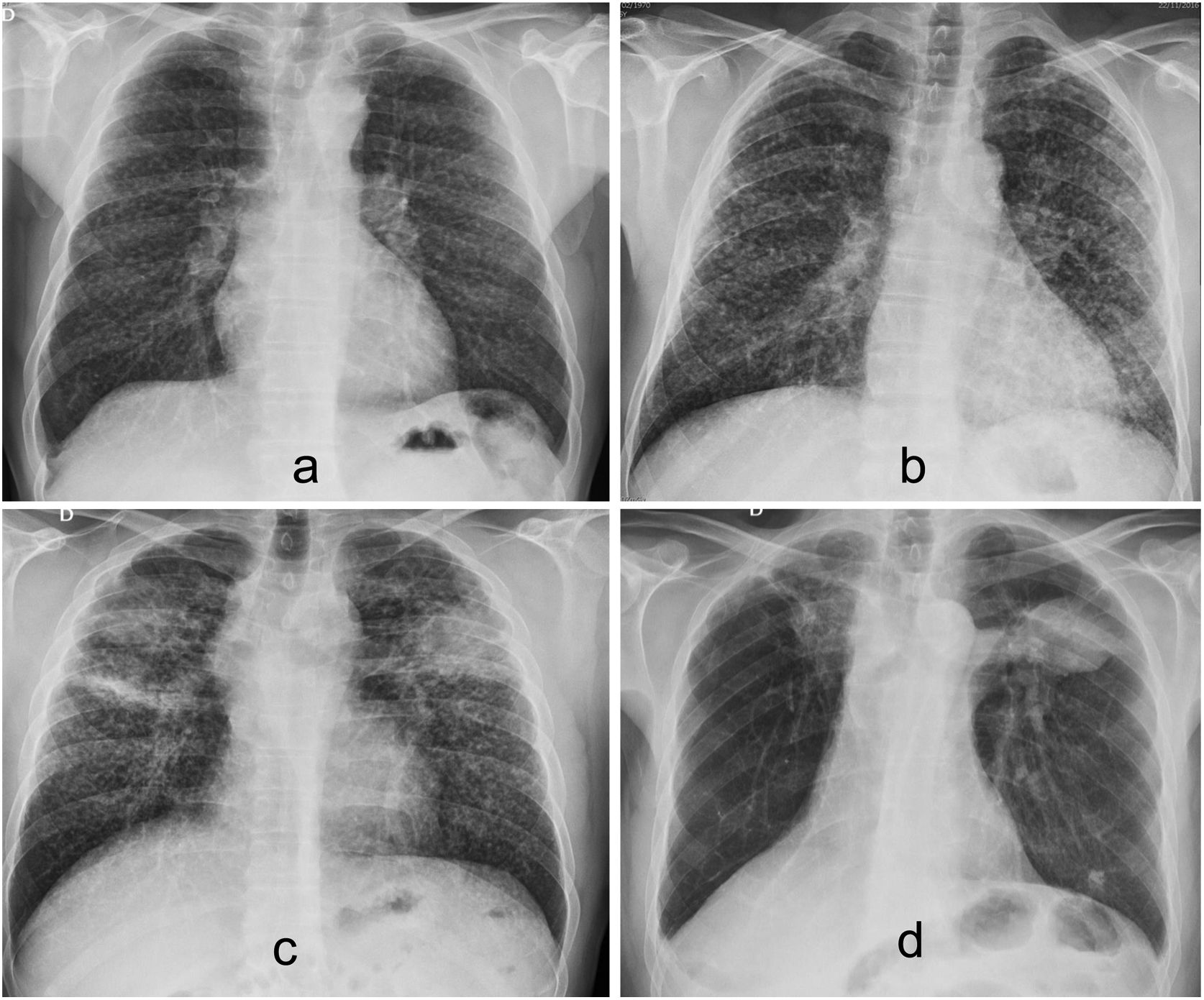

The third form of presentation is accelerated or rapidly progressive silicosis, which usually appears five-to-ten years after exposure, has a rapid progression and is usually associated with exposure to high concentrations of silica. The radiological, clinical, and pathological characteristics are the same as those of the chronic forms. However, the larger ILO classification “r” type nodules predominate and evolve into PMF in about five years (Fig. 5).

In terms of differential diagnosis, the radiological findings of silicosis may be similar to those of miliary tuberculosis, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, alveolar microlithiasis, sarcoidosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, haemosiderosis, and some respiratory infections. In some cases the differential diagnosis is difficult, and may require obtaining a histological sample.

The role of F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose(FDG) positron-emission tomography in the evaluation of PMF masses has not been clearly established, and intense FDG uptake has been described in fibrotic masses and lymph nodes mimicking a neoplastic process.26

Silicosis is a predisposing factor for tuberculosis, especially in patients with complicated silicosis. This common association between tuberculosis and silicosis is found in up to 25% of workers. In addition, tuberculosis aggravates the manifestations of silicosis. Silico-tuberculosis should be suspected when a considerable increase in the profusion or size of the lesions is observed, when the PMF masses cavitate, or when a “tree-in-bud” pattern is identified (Fig. 6).

Silica was recognised as a carcinogenic agent by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 1997. The association with lung cancer is greater in those patients with established silicosis than in patients solely exposed.27 It can be difficult to differentiate PMF masses from neoplastic lesions, and CT-guided percutaneous biopsy is sometimes necessary.

Silica inhalation also causes emphysema and chronic bronchitis, even in the absence of smoking.28

Coal workers’ pneumoconiosisCoal workers' pneumoconiosis (CWP) results from the inhalation and deposition of coal dust particles. Additionally, coal mine dust can contain high concentrations of silica.29

Its incidence has decreased significantly in Spain, since currently there are hardly any active coal mines here.

From a histological point of view, CWP and silicosis are two different diseases, although their radiological findings are comparable.4,30

The only differences are that CWP nodules have less well-defined margins and lymph node calcification is less common than in silicosis.31

Caplan syndrome is a rare complication of CWP that occurs simultaneously with manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis in the joints. In this disorder, peripheral pulmonary nodules with the histopathology of rheumatoid nodules develop on a background of pneumoconiotic opacities. Radiographically, these workers develop peripheral nodules and masses typically bilateral from 5mm to 5cm in size. Unlike pneumoconiotic masses, they can develop rapidly over a period of weeks and may cavitate or calcify.

AsbestosisAsbestos is a natural fibrous magnesium silicate that is used as a thermal insulator. Occupational exposure usually occurs when working with insulation, iron and steel, brakes, ship and building construction, and in the textile industry. Cases of non-occupational exposure have been described among the household members of workers exposed to asbestos.

Clinical manifestations usually do not appear until 20 years after the start of exposure. Despite the fact that its use has been prohibited in Europe since 2004, multiple cases of pathology associated with asbestos continue to be identified.

Chronic exposure to asbestos can cause different diseases, both in the pleura and in the lungs. In the pleura we may find pleural effusion, pleural plaques, diffuse pleural thickening or mesothelioma. Asbestos-associated pulmonary entities are rounded atelectasis, asbestosis and lung cancer.

Asbestosis is an interstitial fibrosis secondary to exposure to asbestos. In the initial phase of the disease, chest radiograph shows a predominantly basal reticulonodular interstitial pattern. Given that in mild forms, lesions in the posterior basal segment of the lungs predominate, and to avoid confusion with physiologic gravitational oedema, HRCT should be performed with the patient in the prone position.

HRCT findings include subpleural, inter- and intralobular septal thickening, curvilinear subpleural lines, parenchymal bands with “crow's feet” morphology, a “honeycomb” pattern, and traction bronchiectasis (Fig. 7).

More than 90% of cases of asbestosis show visible pleural changes on CT, which is useful when proposing the differential diagnosis between asbestosis and other diffuse lung diseases.

Hard metal pneumoconiosisThe hard metal alloy is made up of tungsten and cobalt. It affects, among others, diamond polishers.

Chest radiography may be normal or show a diffuse interstitial pattern. On CT, the findings are similar to those seen in sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with a diffuse reticulonodular pattern, ground-glass areas, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and lymphadenopathy.26,28 Unlike what occurs in other pneumoconioses, radiological findings may slowly disappear if exposure ceases.

Benign or inert dust pneumoconiosisThese pneumoconioses are caused by inhalation of iron oxide (pneumosiderosis), tin oxide (stannosis) or barium sulfate (baritosis). Exposure to these inert dusts has no obvious deleterious effects on lung structure and function; only a slight stromal reaction is observed.32

Pneumosiderosis, also known as Welder's lung, is caused by inhalation of iron oxide in fumes. It is associated with chronic bronchitis, pneumoconiosis, and lung carcinoma. Chest radiography shows small nodules in the middle lung fields and perihilar areas. These abnormalities disappear upon cessation of exposure.

HRCT shows centrilobular micronodules with poorly defined contours and diffuse distribution in the lung fields. In some cases, the nodules take on a branched morphology (“tree in the bud”) (Fig. 8). Ground glass areas, areas of honeycombing, or emphysema may be seen less frequently.33,34

BerylliosisBeryllium is used in dentistry, electronics, nuclear, and aerospace industries. Berylliosis is a T-cell mediated granulomatosis due to hypersensitivity to inorganic beryllium dust. Chest radiograph is usually normal but may show a reticulonodular pattern, predominantly in the middle and upper fields (Fig. 9a). HRCT findings are similar to those of sarcoidosis, with small parenchymal nodules located in the peribronchovascular region and the interlobular septa (Fig. 9b).

Other less common findings are a ground glass pattern, the presence of honeycombing, and thickening of the bronchial walls. There may also be mediastinal and hilaradenopathies.35

Chemical pneumonitisThe irritating gases dissolve in the water of the respiratory tract mucosa, causing an inflammatory response, usually secondary to acidic or alkaline radicals. Exposure to these irritating gases predominantly affects the airway causing tracheitis, bronchitis and bronchiolitis. Some of these gases may be toxic directly (e.g., cyanide, carbon monoxide, perfluoroisobutene) or indirectly through oxygen displacement and consequent hypoxia (e.g., methane, carbon monoxide).

Chest radiograph findings consist of patchy or confluent consolidations secondary to pulmonary oedema (Fig. 10).

Chemical pneumonitis due to accidental inhalation of carbon monoxide. (a) Posteroanterior chest radiograph: bilateral pulmonary consolidations predominantly in the perihilar regions and upper lung fields. (b) HRCT: bilateral ground-glass pattern with involvement of posterior areas, with reticulation and small superimposed pulmonary consolidations.

CT can be used in patients who develop symptoms late with respect to exposure, visualising bronchiolitis obliterans with a mosaic pattern with ground-glass opacities, bronchial wall thickening, andbronchiectasis.36

Hypersensitivity pneumonitisHP, also known as extrinsic allergic alveolitis, is a granulomatous interstitial lung disease caused by the inhalation of organic or inorganic microparticles 16,37 with a size between 1 and 5μm (Table 1).

Antigens related to the most common forms of hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

| Type of antigen | Specific antigen | Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Thermoactinomyces vulgaris | Mushroom worker's lung |

| Streptomyces thermohygroscopicus | Farmer's lung | |

| Thermoactinomyces candidus | Air-conditioner lung | |

| Fungi | Penicillium spp. | Suberosis (cork workers) |

| Acremonium strictum | Wood dust-related lung injury | |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Bird fancier's lung | |

| Mycobacteria | Mycobacterium avium | Hot tub lung |

| Proteins | Immunoglobulin A | Bird fancier's lung |

| Cotton | Byssinosis | |

| Bird feathers | Feather duvet lung | |

| Chemical products | Isocyanate | Isocyanate lung injury |

| Bordeaux mixture | Vineyard sprayer's lung |

The number of agents is very high, in most cases being inhaled material contaminated with fungi, bacteria and protozoa. Also isocyanates in paints, foams and adhesives. New agents are constantly being added as a cause of hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Only a small percentage of people exposed to the antigen will develop HP (5%–15%)38 and in 40% of patients, the causative antigen is unknown.39

It is more common in middle-aged women and non-smokers and accounts for 1.5%–13% of interstitial lung diseases.

Inhaled antigens cause, in susceptible and previously sensitised individuals, a granulomatous inflammatory reaction of the alveolar and distal airways, with alveolar lymphocytosis (mainly CD8 lymphocytes), as well as activation of alveolar macrophages.37

The growing list of antigens can be divided into three large groups: microbiological agents, proteins, and chemical agents.

Classically, three forms of presentation have been identified40: acute, subacute and chronic.

Clinical, radiological, and pathological findings may overlap and are unrelated to disease prognosis.41 Due to this, a new classification has been proposed based on the presence or absence of fibrosis, which is the determining factor of the prognosis16,37:

- -

Inflammatory HP (non-fibrotic): develops in a few weeks; is reversible in most patients and has a good prognosis.

- -

Fibrotic HP: develops over months; abnormalities progress to fibrosis and it has a worse prognosis.

In general, there is a lack of consensus regarding the diagnostic criteria and a multidisciplinary approach is required that involves clinicians, radiologists, andpathologists.16

With a history of antigenic exposure and excluding other interstitial diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or autoimmune diseases, compatible radiological findings are sufficient to make the diagnosis of fibrotic HP,16,42 thus avoiding the need for invasive tests.

The histopathological process consists of inflammation of the bronchioles, peribronchiolar tissue and alveoli.43

In fibrotic HP, fibrotic changes overlap with the inflammatory phase findings.44

Chest radiograph has limited usefulness since up to 20% of patients present with no abnormalities.45 When present, the most common findings are patchy or diffuse ground-glass opacities and a nodular or reticulonodular pattern with relative preservation of the lung bases. More rarely, alveolar consolidations can be observed.

In inflammatory HP, CT can be normal or show small (<5mm) nodules with ground-glass attenuation that are centrilobular (Fig. 11) or nodules that are randomly distributed, which can even mimic a miliary pattern and areas of air trapping predominantly in the middle and upper fields. However, the involvement can also be diffuse.46

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. (a) Posteroanterior chest radiograph: faint bilateral diffuse micronodular pattern. (b) HRCT: ground-glass centrilobular nodules with poorly defined bilateral borders (black arrows), alternating with patchy areas of lower attenuation (white arrows) that form a “mosaic pattern”.

An expiratory CT should be included in the study protocol of these patients to assess for air trapping (focal areas of the lung, the attenuation of which does not increase with expiration).

In the inspiratory images a mosaic pattern can be identified47 (well-defined areas of variable lung attenuation). These findings give rise to the "head cheese" sign, although in recent guidelines,37 this name has been replaced by the "three-density pattern" (Fig. 12a), which consists of a combination of ground-glass opacities, hypodense and hypovascularised areas (secondary to small airway obstruction), and areas of the relatively preserved lung with abrupt geographic delimitation.48,49 Less frequently, thin-walled cysts may appear, with a diameter of less than 15mm.50

Inflammatory (a) and fibrotic (b) hypersensitivity pneumonitis in two different patients. a) Inspiratory HRCT: patchy lesions with ground-glass density together with other geographical areas of lower attenuation and others of normal lung ("three-density" pattern). b) HRCT: irregular reticulation, traction bronchiectasis, "honeycomb" pattern and "mosaic pattern". It has both a central and peripheral distribution.

There is no septal thickening or architectural distortion. Enlarged lymph nodes may appear in the mediastinum.

In fibrotic HP (Fig. 12b), irregular reticulations with distortion of the lung architecture, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing are seen classically with both central and peripheral distribution and predominantly in the upper and middle lung fields.46,51 There may be small centrilobular nodules, mosaic attenuation, and air trapping.48

The differential diagnosis of inflammatory HP is with respiratory bronchiolitis, atypical infections and alveolar haemorrhage, among others. In fibrotic HP, the differential diagnosis should be made with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.51

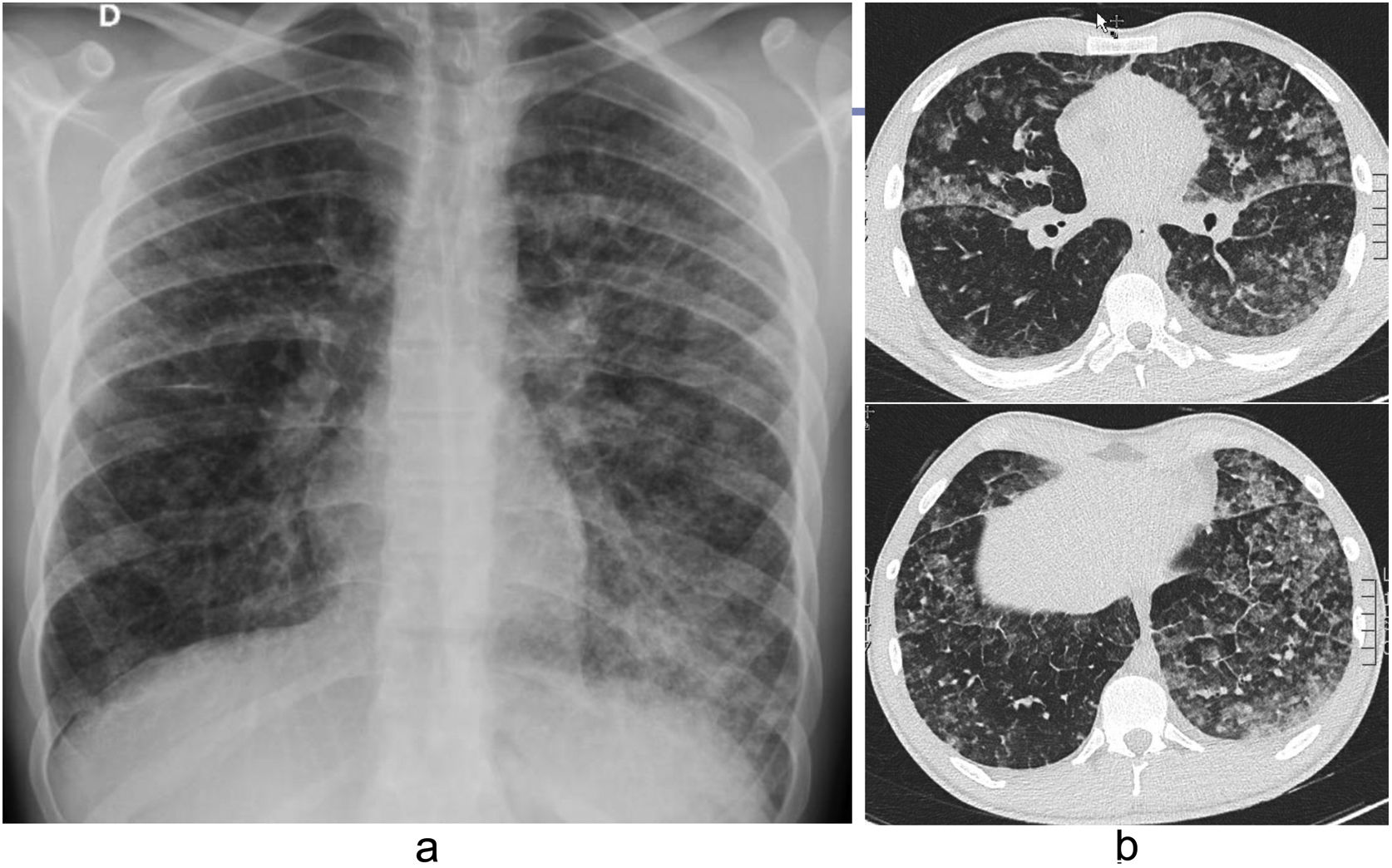

E-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injuryThe use of electronic cigarettes is recent (2006), with an exponential increase in their consumption, especially widespread among young people and adolescents. These devices vaporise a liquid composed of a mixture of chemical substances,52 which often include nicotine, propylene glycol, glycerine, flavourings and other organic components. They can also be used to administer tetrahydrocannabinol. These products cause vascular damage, endothelial dysfunction, and acute lung damage, known as E-cigarette or Vaping Product Use-associated Lung Injury (EVALI).52,53 The diagnosis of EVALI is one of exclusion and requires a history of use of e-cigarettes in the 90 days before the onset of symptoms, the presence of pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph or chest CT, the absence of infection in the initial evaluation and no evidence of other alternative diagnoses. It is associated with a clinical picture of non-specific symptoms similar to those in a viral infection, and the prognosis is worse in older patients.

Various radiological patterns associated with EVALI have been described, the most representative and frequent being organising pneumonia and diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), with acute eosinophilic pneumonia and alveolar haemorrhage being lesscommon.52

In organising pneumonia on chest radiograph, patients show more pronounced diffuse opacities in central areas (Fig. 13a). Kerley B lines can also be seen. CT reveals diffuse, bilateral, and symmetrical ground-glass opacities (Fig. 13b), preserving the subpleural space, interlobular septal thickening, and a crazy-paving pattern.

Patients with DAD present a greater degree of severity clinically and radiologically, frequently requiring invasive ventilation.

During the acute phase of DAD, chest radiography and CT may show volume loss, with consolidations predominantly in the lower lobes and ground-glass areas, septal thickening, or the crazy-paving pattern.

ConclusionsAlthough inhalational lung diseases are fundamentally caused in the workplace, they can also occur in domestic and recreational settings. Radiology plays a determining role in the diagnosis and management of these entities, but on many occasions, the findings are non-specific, so a multidisciplinary approach is essential to assess the patient from an overall perspective, always taking into account their employment history. The participation of the radiologist in multidisciplinary committees is essential as it helps to make an early diagnosis and to improve patient management and the implementation of appropriate preventive measures.

AuthorshipAll the authors have contributed substantially to the preparation of the different sections of this chapter on "Inhalational Lung Diseases", bibliographic review, image selection, the conception and design of the work, the drafting, the critical review of the intellectual content and the final approval of the submitted version.

- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study:

- 2.

Study conception:

- 3.

Study design:

- 4.

Data acquisition:

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation:

- 6.

Statistical processing:

- 7.

Literature search:

- 8.

Drafting of the article:

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions:

- 10.

Approval of the final version:

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.