Palpable tumors in children are a common reason for consulting a radiologist. The differential diagnosis is extensive and considerably different from that used in adults. Some of the etiologies of palpable tumors are little known outside of pediatrics.

The most commonly used imaging test is ultrasonography, because in addition to being harmless and cost-effective, it is conclusive in most cases.

Most palpable lesions in children are benign; it is estimated that only 1% are malignant. Knowing these lesions enables the correct diagnosis without the need to resort to unnecessary, sometimes invasive tests, thus avoiding delays in treatment when more severe disease is present.

This article aims to review the clinical and radiological characteristics of the palpable lesions that are most common in pediatric patients, explaining the key features that enable accurate diagnosis.

La presencia de una tumoración palpable en un niño es un motivo de consulta frecuente en Radiología. El diagnóstico diferencial es extenso y considerablemente diferente al del adulto. Algunas de las etiologías son poco conocidas fuera del ámbito pediátrico.

La prueba de imagen más utilizada es la ecografía, porque además de inocua y coste-efectiva, es concluyente en la mayoría de los casos.

La mayor parte de las lesiones son de naturaleza benigna. Se estima que solo el 1% terminan en un diagnóstico de neoplasia maligna. Conocerlas permite hacer un diagnóstico correcto, sin tener que recurrir a pruebas innecesarias y a veces invasivas, así como evitar retrasos en el proceso asistencial cuando nos encontremos ante una enfermedad de mayor gravedad.

El objetivo de este artículo es repasar las características clínico-radiológicas de las tumoraciones palpables más frecuentes en el paciente pediátrico, explicando los datos clave que permitan hacer un diagnóstico preciso.

The presence of a palpable mass in a child is a common reason for consultation for both paediatric and general radiologists. The aetiologies differ considerably from those found in adult patients, and some of them are relatively unknown outside the paediatric setting. Although they cause a great deal of anxiety, the vast majority are benign or even self-limiting lesions. It is estimated that only 1% are eventually diagnosed as malignant1.

The first (and often last) imaging test tends to be an ultrasound scan. In addition to its well-known advantages, it allows us to examine the patient clinically. Many lesions have a characteristic appearance and location and we often have a suspected diagnosis even before the scan. As a rule, linear transducers with the highest frequency available should be used, for their greater spatial resolution. Occasionally, it is necessary to resort to lower-frequency probes if the lesion extends so deep that it is out of range of the high-frequency probes. A Doppler ultrasound study can measure blood flow in the lesion. The new microvascular techniques are particularly useful, as they are capable of detecting very low-velocity flows without movement artifacts which are not visible with colour Doppler or power Doppler2. Quantitative sonoelastography is a new and promising technique for characterising soft tissue tumours more accurately3,4.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used when ultrasound does not provide a conclusive diagnosis or the deep extension prevents full assessment. It is particularly helpful on account of its excellent contrast resolution, as well as for providing topographic data and information on chemical composition, vascularisation and cellularity5. However, apart from less availability and higher cost, the need for sedation in uncooperative patients limits its use in the paediatric setting.

Computed tomography (CT) is not used in this healthcare context because it uses ionising radiation and does not provide as much information as MRI. The exception would be myositis ossificans.

X-rays rarely give conclusive information about palpable lesions, but the fact that they are widely available means they have often already been performed before the patient reaches the Radiodiagnostics department.

When a soft tissue lesion is not clearly self-limiting or benign, it should be closely monitored to detect growth or changes in its morphology or consistency, and in most cases it should be resected or at least biopsied. Imaging tests are also useful for guiding the biopsy procedure and for planning the surgery.

The aim of this article is to review the main palpable tumours in Paediatrics, explaining the key data that enable an accurate diagnosis. Due to the magnitude of the subject, we have had to divide it into two parts to include as many of the different lesions that we might encounter as possible.

Lymph nodes and lymphadenopathyLymph nodes are highly organised, encapsulated collections of lymphocytes and other immune system cells located along lymphatic channels throughout the body6.

Palpable lymph nodes are very common in paediatric patients7. Up to 90% of children four to eight years of age have palpable cervical lymph nodes on clinical examination8.

If the examination or evolution are atypical, ultrasound is usually the initial test used to classify the lesion as a reactive lymph node (“benign”) or pathological lymphadenopathy (cancerous, necrotic or suppurative).

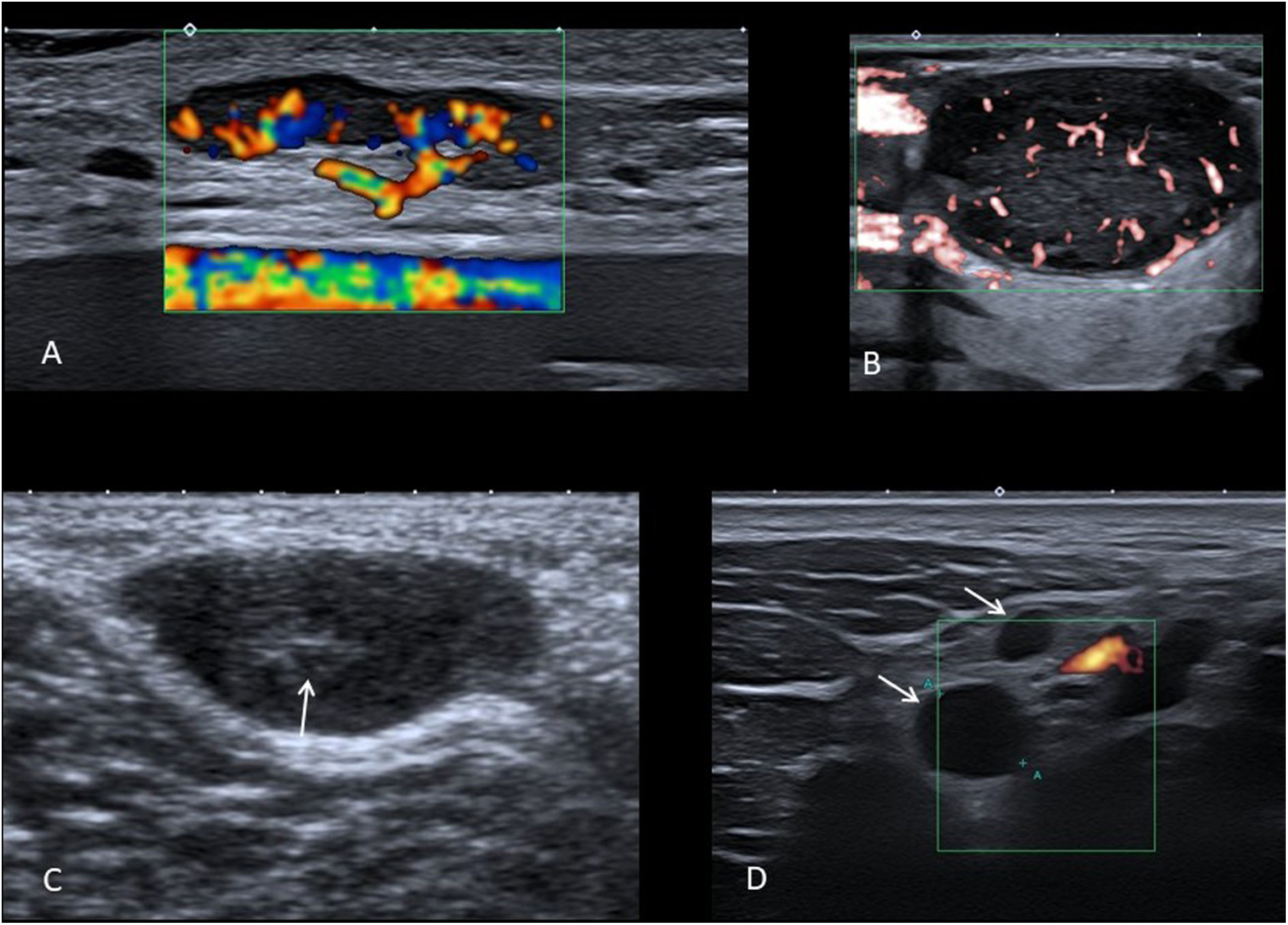

The ultrasound criteria that indicate a reactive or pathological origin of the node should be taken together and the diagnosis not exclusively based on just one. A normal node is oval and hypoechoic, with an echogenic central hilum with central vascularisation9 (Fig. 1A).

A) Colour Doppler ultrasound image showing a benign oval node with fatty hilum and normal flow distribution. B) Microvascular Doppler ultrasound image showing a pathological lymph node, with rounded morphology, without fatty hilum and with predominantly peripheral disordered flow. C) Grey-scale ultrasound of synovial sarcoma in the popliteal fossa of a 9-year-old boy, which has oval morphology and a hyperechoic centre (arrow), which should not be confused with a hilum. D) Power Doppler ultrasound image where supraclavicular lymphadenopathy with a “pseudocystic” appearance (arrows) is identified in a 14-year-old girl with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The size of the node in itself is not very useful for establishing whether or not it is benign. In children, we find many reactive nodes larger than the classic limit of 1 cm in the minor axis, enlarged by physiological stimulation of the immune system, while some pathological nodes are below this size.

Pathological lymph nodes are usually spherical (Fig. 1B). The exception is the reactive intraparotid and submental nodes, which are also often spherical.

The presence of a hyperechoic central fatty hilum also suggests a reactive node, while its absence should prompt suspicion of pathological lymphadenopathy. We have to be sure that it is a true hilum and not a hyperechoic centre, which would involve other differential diagnoses, such as a soft tissue sarcoma (Fig. 1C) or a neurogenic tumour. In addition to the presence of hilum, we need to confirm that the node has a normal ultrasound pattern with homogeneous thickness of the cortical bone and the absence of calcifications or anechoic areas.

In the colour Doppler study, the normal flow of a lymph node consists of vessels that branch from the hilum (Fig. 1A), while disordered peripheral distribution flow is typical of pathological lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1B). In small benign lymph nodes or in highly necrotic lymphadenopathy, it is common not to detect flow with colour Doppler or power Doppler ultrasound, with microvascular techniques being considerably more sensitive in these situations.

Special care must be taken not to confuse an anechoic lymph node with a cystic lesion. A “pseudocystic” appearance is common in lymphomas (Fig. 1D), especially if probes with an insufficiently high frequency are used10. A cyst-like appearance can also be seen in metastatic lymph nodes with extensive necrosis, as well as in lymphadenopathy which is suppurative or with caseous necrosis.

If a node meets the typical criteria for being benign, a watchful waiting approach is usually taken unless there are clinical signs of bacterial infection, in which case it is treated with antibiotics. However, if it seems to have a pathological origin or does not respond to antibiotic therapy, histological and microbiological tests are necessary. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is usually performed or, particularly if lymphoma is suspected, the lymph node is removed to determine the therapeutic approach.

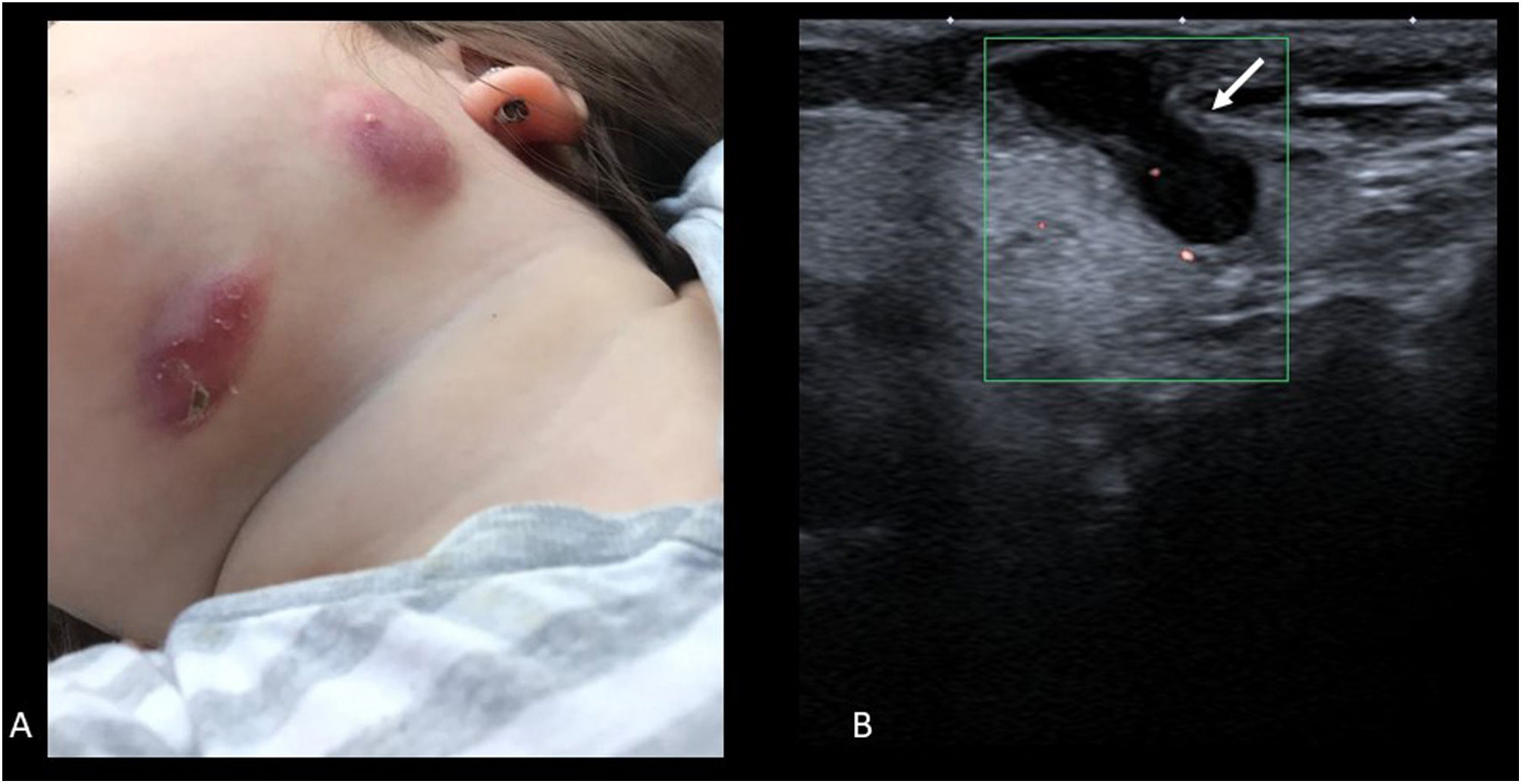

Cervical adenitis due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria is a relatively common disease and almost exclusive to children from one to five years of age. It is little known by non-paediatric radiologists, which often leads to delayed diagnoses. The reason for consultation is normally the presence of a lateral/cervical or submandibular nodule, with purple discolouration of the skin (Fig. 2A). In more advanced cases, the lesion fistulises to the skin surface (“scrofula”). In Europe, 80% are caused by Mycobacterium avium.

On ultrasound, there may be one or more affected lymph nodes. They are rounded, hypoechoic and usually have necrotic areas with a cystic appearance. If the lesion has opened to the skin, the fistulous tract can be seen (Fig. 2B). The diagnosis is confirmed with FNA and treatment is resection of the lesion; this is curative and prevents aesthetically undesirable scar changes. It rarely requires antibiotic therapy.

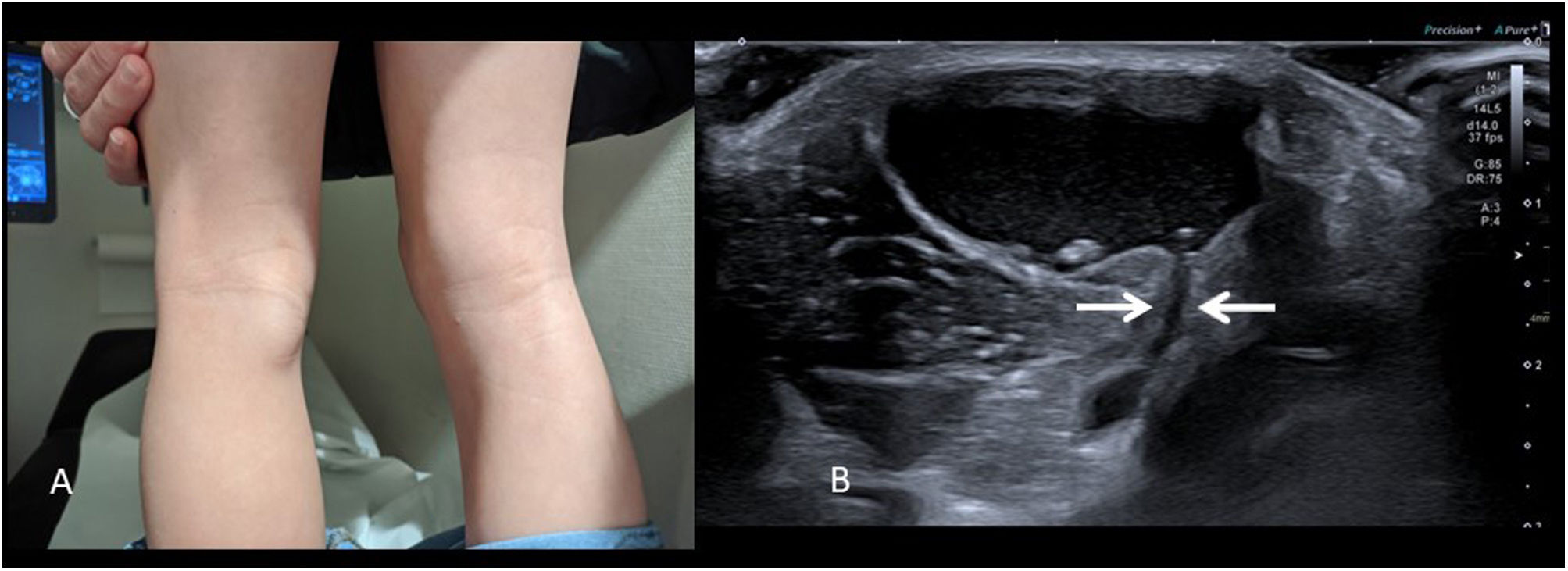

Baker's cystThe popliteal cyst or Baker’s cyst is common in adults, but is often not considered in paediatric patients despite being the most common mass in the popliteal fossa in children. Unlike in adults, in children they are hardly ever associated with rheumatic or degenerative disease.

It consists of a “herniation” of the joint capsule filled with fluid through the space between the tendon of origin of the medial gastrocnemius muscle and the tendon of the semimembranosus.

It is not usually painful and presents as a firm but compressible mass in the medial and caudal part of the popliteal fossa (Fig. 3A). Diagnosis is direct with ultrasound, identifying a well-defined cystic structure that communicates with the knee joint through the semimembranosus-gastrocnemius bursa (Fig. 3B). The presence of joint effusion can be ruled out in the same examination. Occasionally they rupture, adopting a very atypical radiological appearance with the presence of echogenic content, capsular thickening and fluid, and inflammatory changes in the surrounding tissues11, which complicates diagnosis.

In paediatric patients without associated joint disease, they resolve spontaneously, and a watchful waiting approach is recommended12.

GanglionThe synovial ganglion is another accumulation of synovial fluid, but in this case it is due to a rupture in the joint capsule and extravasation of the fluid into the surrounding tissues. The term “synovial cyst” is not correct, as these lesions do not have their own wall. It is also a common lesion in children, especially on the palmar surface of the wrist (in adults it is usually on the dorsal surface) from the scapholunate joint. Ganglions are not painful, and if there is pain, the cause should be investigated and not be attributed to the ganglion.

Although the clinical diagnosis is easy, ultrasound is often prescribed to reassure parents. Ultrasound allows the patient to be examined in the position in which the lump is most obvious (for example, extending or flexing the wrist) and to confirm that it is indeed a cyst. As in Baker’s cyst, it is necessary to define a clear communication with the joint space or a tendon sheath and the absence of a solid component, because otherwise we could be labelling another type of cystic lesion or even a hypoechoic soft tissue tumour as a ganglion13.

The rate of spontaneous resolution in children is high, around 80%14. If they persist, they can be treated surgically, although this is not usual in asymptomatic lesions15.

Epidermoid and dermoid cystsThese cysts originate during embryological development due to a failure in the separation between the superficial ectoderm and the adjacent structures. Some ectodermal elements become deeply trapped forming an inclusion cyst.

Epidermoid cysts are only lined by squamous epithelium and are filled with laminated keratin, while dermoid cysts also contain other cutaneous elements, such as hair, sebaceous glands and sweat glands16. They are a common cause of palpable mass in children and the lesion most frequently resected in this age group.

They are most often found in areas of embryological fusion, such as points of closure of cranial sutures or the neural tube17, occurring mainly in the head and neck, suprasternal notch, trunk and anogenital region, although they can appear in any part of the body. In the head and neck they are mostly located in relation to the cranial sutures or in the midline. The frontozygomatic suture, at the “tail” of the eyebrow, is the most typical site. In the midline they are more common in the floor of the mouth, the nasal region, the glabella (between the eyebrows) and the anterior fontanel. These cysts can occur superficial or deep to the periosteum, including intracranially18,19.

They usually present as painless palpable masses of variable consistency. They may be well defined and mobile or attached to deep planes. They are usually discovered accidentally, so although most are present at birth they tend to be detected in older children. The skin covering them can be normal or look slightly bluish, reddish or whitish. They are usually less than 3 cm in size and solitary (multiple lesions are associated with some types of intestinal polyposis such as Gardner syndrome). They are slow-growing, due to the gradual accumulation of skin-derived products. Sometimes they become infected or rupture, triggering an inflammatory reaction in surrounding tissues and thickening with loss of wall definition, which can give them an aggressive appearance in imaging tests20.

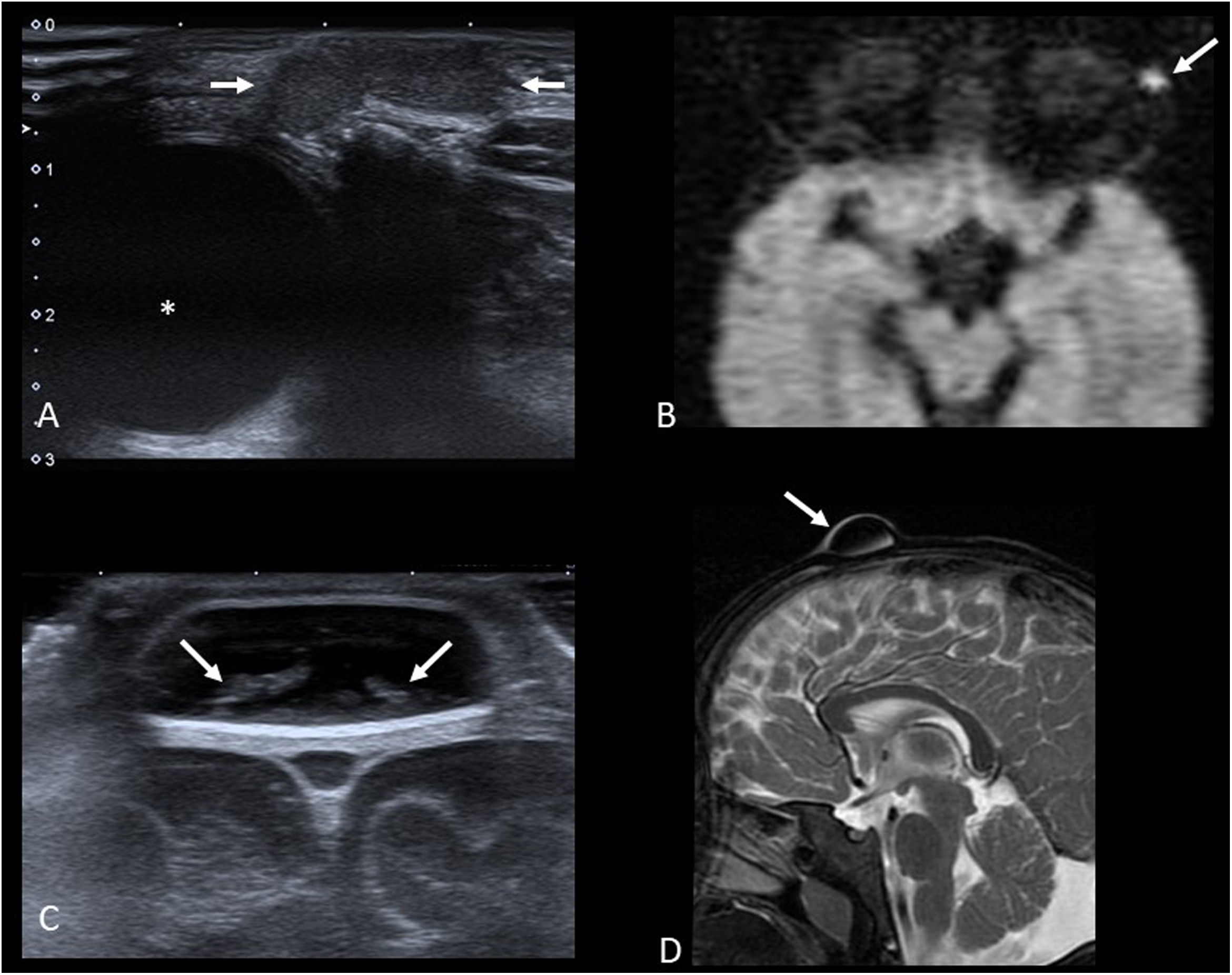

Imaging studies usually begin with ultrasound (Fig. 4A and C) to confirm the diagnosis and assess the size of the cyst. Both types of cysts are normally indistinguishable, appearing as well-defined round or oval nodules. They have variable echogenicity depending on their content, from anechoic to diffusely echogenic, with good sound transmission and no flow in the Doppler study. When they are located adjacent to a bone surface, they typically cause bone remodelling.

A) Axial grey-scale ultrasound image showing an epidermoid cyst in the “tail” of the left eyebrow (arrows) in a one-year-old child (* eyeball). B) Axial diffusion-weighted MRI image of another patient (3 years old). We can see the restricted diffusion typical of epidermoid cysts (arrow). C) Coronal plane grey-scale ultrasound image of the anterior fontanelle of a 7-month-old infant. It shows a dermoid cyst with echogenic content (arrows). D) T2-weighted MRI image with fat saturation in the sagittal plane of the same patient. The lesion is hypointense (arrow) as the signal from the lipid content has been suppressed.

If the location and ultrasound findings are typical, no other imaging tests are necessary. If the diagnosis remains uncertain or deep involvement is suspected, the study needs to be completed with other imaging tests, usually MRI.

MRI does often allow differentiation between the two types of cyst. The epidermoid cysts normally have a signal intensity equal to that of fluid in all the sequences and their most characteristic aspect is the restricted diffusion due to keratin content (Fig. 4B). Dermoid cysts usually have different proportions of fat content, which is why they show variable signal intensity, frequently high on T1-weighted and low on T2-weighted sequences with fat saturation (Fig. 4D). Unlike epidermoid cysts, they do not show restricted diffusion and fluid-fluid levels are sometimes identified in their interior.

Although CT can be helpful, it is used almost exclusively in cases of skullcap involvement.

They are benign lesions but are usually removed due to their potential growth.

HaemangiomasHaemangiomas are true vascular tumours with proliferation and hyperplasia of endothelial cells. The term should not be used to refer to vascular malformations21.

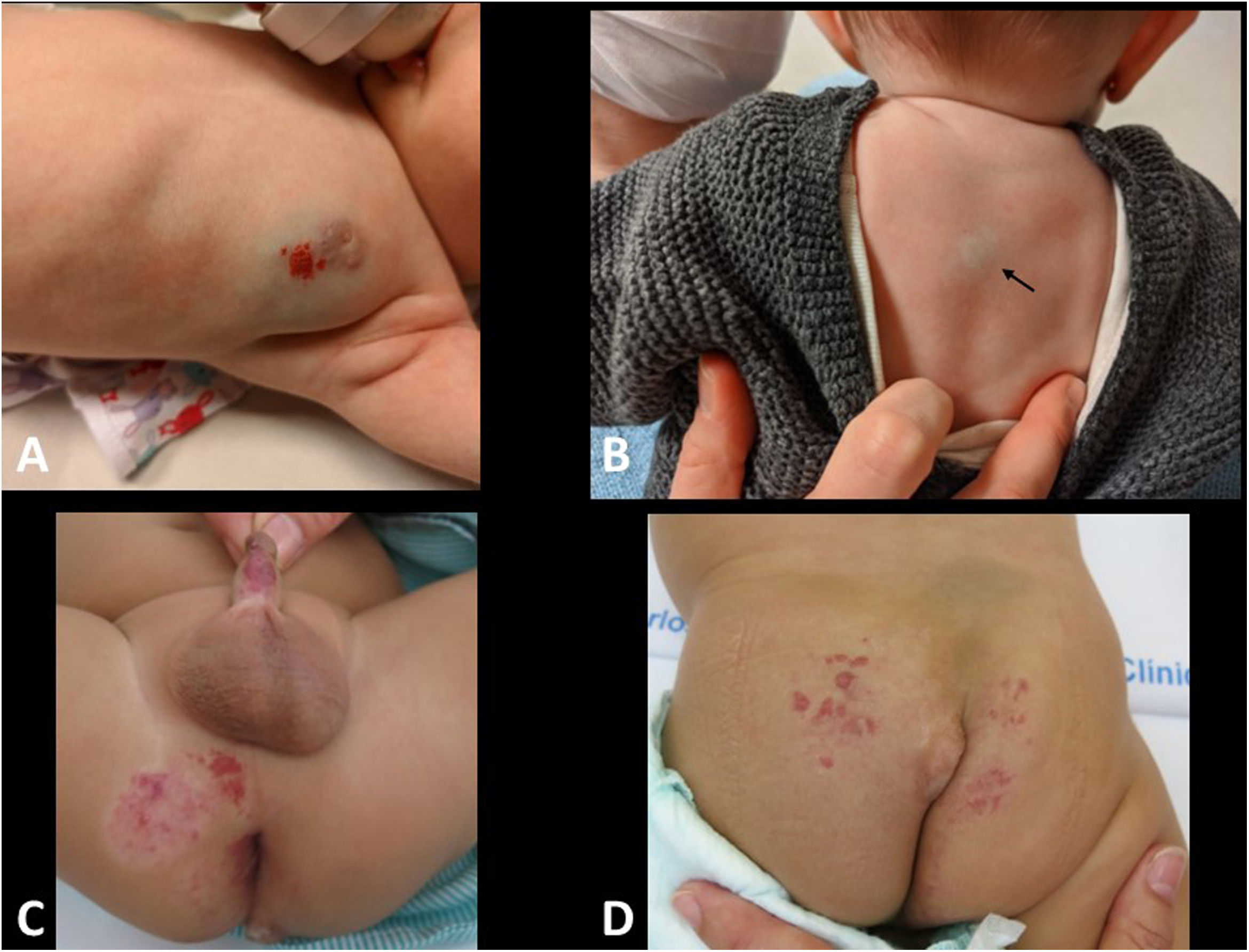

Infantile haemangioma (IH) is the most common soft tissue tumour in infants, occurring in up to 5%. Diagnosis is usually clinical, as its appearance and raspberry-red colouration are very characteristic22. In deep IH, skin colour is usually bluish or even normal, which complicates the clinical diagnosis (Fig. 5A and B).

A) Five-month-old infant with infantile haemangioma in the mammary region, with deep (purple) and superficial (raspberry red) components. B) Three-month-old infant with deep infantile haemangioma on the back (arrow). C and D) LUMBAR association (Lower body haemangioma, Urogenital anomalies, Ulceration, Myelopathy, Bony deformities, Anorectal malformations, Arterial anomalies, and Renal anomalies). Six-month-old infant with perineal and sacral infantile haemangioma, along with sacral lipoma. The MRI (not shown) showed tethered cord associated with intradural lipoma (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

They may be present at birth, but they usually become apparent in the first two weeks of life, grow rapidly during the first few months (proliferative phase), and then slowly involute after a plateau phase. Although on average they disappear at around five years of age, some can persist up to the age of ten. It is not uncommon for residual scarring, lipomatous or telangiectatic areas to remain.

Large facial or lumbar lesions (>5 cm in diameter) may be the first manifestation of a more complex clinical condition, such as PHACES syndrome (Posterior fossa brain malformations, large facial Haemangiomas, anatomical anomalies of the cerebral Arteries, aortic coarctation, Cardiac anomalies, Eye abnormalities and Sternal anomalies) and the LUMBAR association (Lower body haemangioma, Urogenital anomalies, Ulceration, Myelopathy, Bony deformities, Anorectal malformations, Arterial anomalies and Renal anomalies) (Fig. 5C and D) 23,24. In the case of multiple lesions (more than 5), it is advisable to rule out visceral involvement, with the liver being the most commonly affected organ. Lesions close to the airway, such as in the neck or nose, should be studied carefully to rule out compromise of the airway.

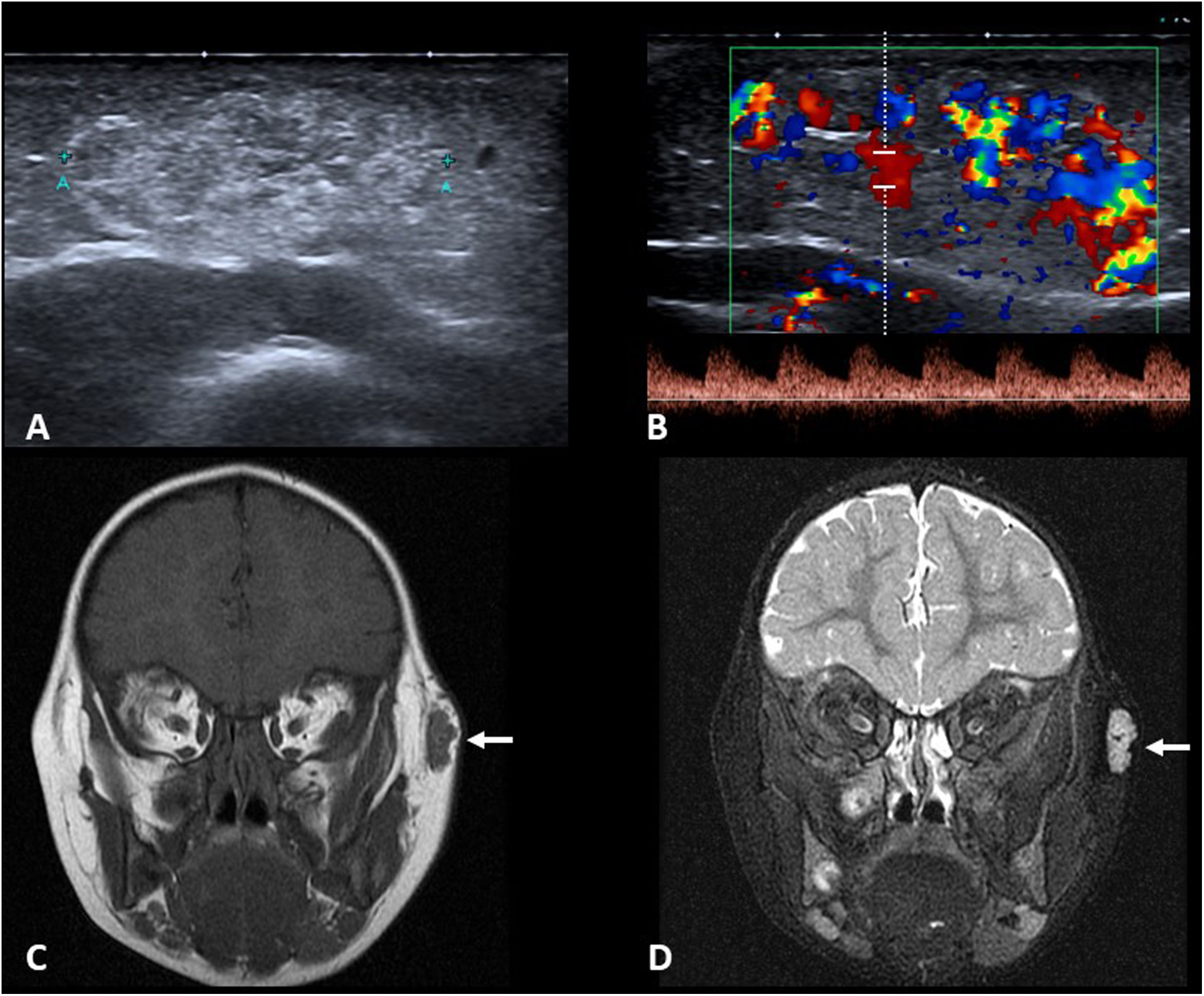

Ultrasound is the most widely used radiological test for the study of IH (Fig. 6A and B). It permits confirmation of diagnosis in deep lesions, and it is particularly important to distinguish between it and a vascular malformation, as management and prognosis are completely different. In the proliferative and plateau phases, IH is a well-defined lesion with lobulated borders and variable but fairly homogeneous echogenicity which does not usually invade adjacent anatomical compartments. It shows abundant low-resistance arterial flow in the Doppler study. When the lesion is studied in the involution phase, the ultrasound findings may be less specific, appearing as nodules or masses with a fatty appearance and without hyperaemia on Doppler ultrasound.

A and B) Grey-scale ultrasound and colour and pulsed Doppler ultrasound of infantile haemangioma on the chest wall of an 8-month-old infant. The image shows a hyperechoic subcutaneous nodule with well-defined lobulated borders, with abundant low-resistance arterial flow. C and D) Coronal T1- and T2-weighted MRI images with fat saturation in a 26-month-old child with facial infantile haemangioma. The lesion (arrows) is hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 with fat saturation, where arterial signal voids can be seen in its central region.

MRI is used to assess possible associated abnormalities (LUMBAR/PHACES) or in lesions with an atypical ultrasound appearance or which are inaccessible to ultrasound scanning due to their location. IH are lesions with well-defined lobulated borders, hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2, with some arterial signal voids and intense enhancement if paramagnetic contrast is administered (Fig. 6C and D).

Congenital haemangiomas (CH) are much less common than IH, but they have a similar appearance radiologically. However, they can be differentiated by the way they evolve and their clinical appearance. A CH is fully developed at birth, and its subsequent evolution is unpredictable. Some involute rapidly (rapidly involuting CH [RICH]), while others only partially involute (partially involuting CH [PICH]) or do not involute (non-involuting CH [NICH]).

Pyogenic granuloma, tufted haemangioma, and its more aggressive form, kaposiform haemangioendothelioma, which can cause Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon, are other haemangiomas with a very low incidence. The clinical picture and the age of the child at the time the lesion appears help to raise the alert.

Although not common, a biopsy is performed if the clinical and radiological findings are atypical. There is an exclusive immunohistochemical marker for IH, regardless of which phase it is in, called GLUT-1. This is a glucose transporter protein that the rest of the above haemangiomas do not express25.

In most cases, IH do not require any treatment, with follow-up only being performed to confirm natural involution. About 10%–15% of IH do require treatment, mainly when they compromise vision (for example, large haemangiomas on an eyelid) or the airway, ulcerate, are in moist and "dirty" areas (under the nappy) or are very disfiguring. These cases respond spectacularly to treatment with oral propranolol26, and surgery is only very rarely necessary27.

Ultrasound makes it possible to assess the efficacy of medical treatment in non-superficial lesions. A decrease in blood flow seen in the Doppler ultrasound study precedes the decrease in the size of the lesion.

Vascular anomaliesVascular anomalies (VA), or malformations, are lesions present at birth which enlarge proportionately as the child grows.

The most widely accepted classification is that of the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA)28,29. It divides them into simple malformations (capillary, lymphatic, venous or arteriovenous) or combined (any combination of 2 or more of the above). In terms of management, they are usually divided into high-flow VA (all those with an arterial component) and low-flow VA (the rest), as this is the criterion for the choice of treatment30.

VA can appear anywhere in the body, and unlike IH they often spread across different anatomical compartments. For that reason, ultrasound may be insufficient and MRI is often necessary to assess deep involvement.

Capillary anomalies (also called “port-wine stains”) are usually superficial, and as diagnosis is based on their presence at birth, appearance and distribution, imaging tests are not required. Imaging tests are sometimes necessary to rule out associated abnormalities (for example, Sturge-Weber syndrome).

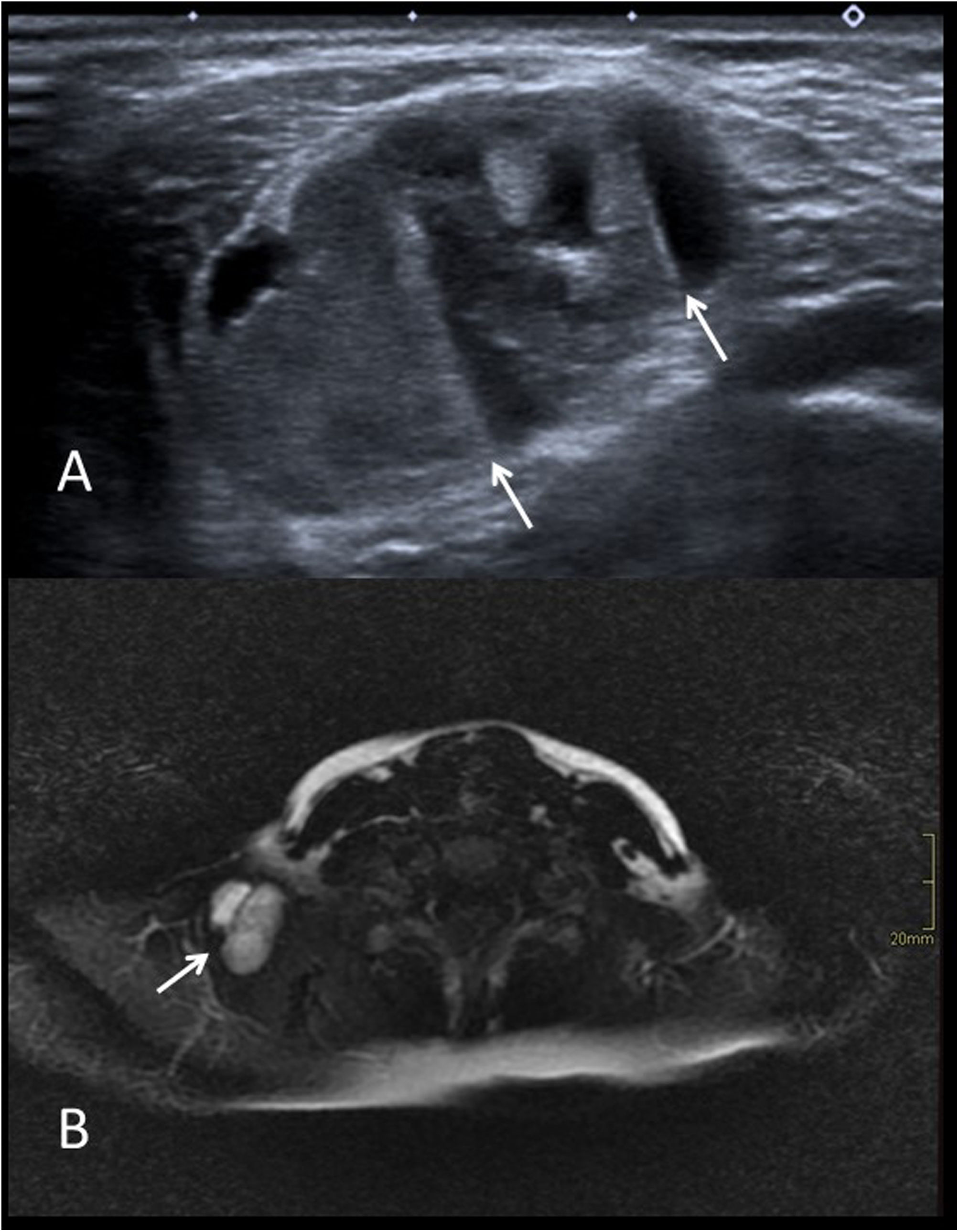

Lymphatic VA are cyst-like masses with fine septa on ultrasound. Fluid-fluid levels may be present, especially if complicated by bleeding or infection. It is not uncommon for some to disappear or decrease in size after an infection. On contrast-enhanced MRI, the walls of the cysts and the septa usually enhance (Fig. 7).

A) Grey-scale ultrasound image of an infected lymphatic vascular malformation in the right supraclavicular region of an 11-year-old girl. Multiple septa and fluid-fluid levels can be seen (arrows). B) Axial T2-weighted MRI image with fat saturation from the same patient. Septa and fluid-fluid levels in the lesion are also visible (arrow).

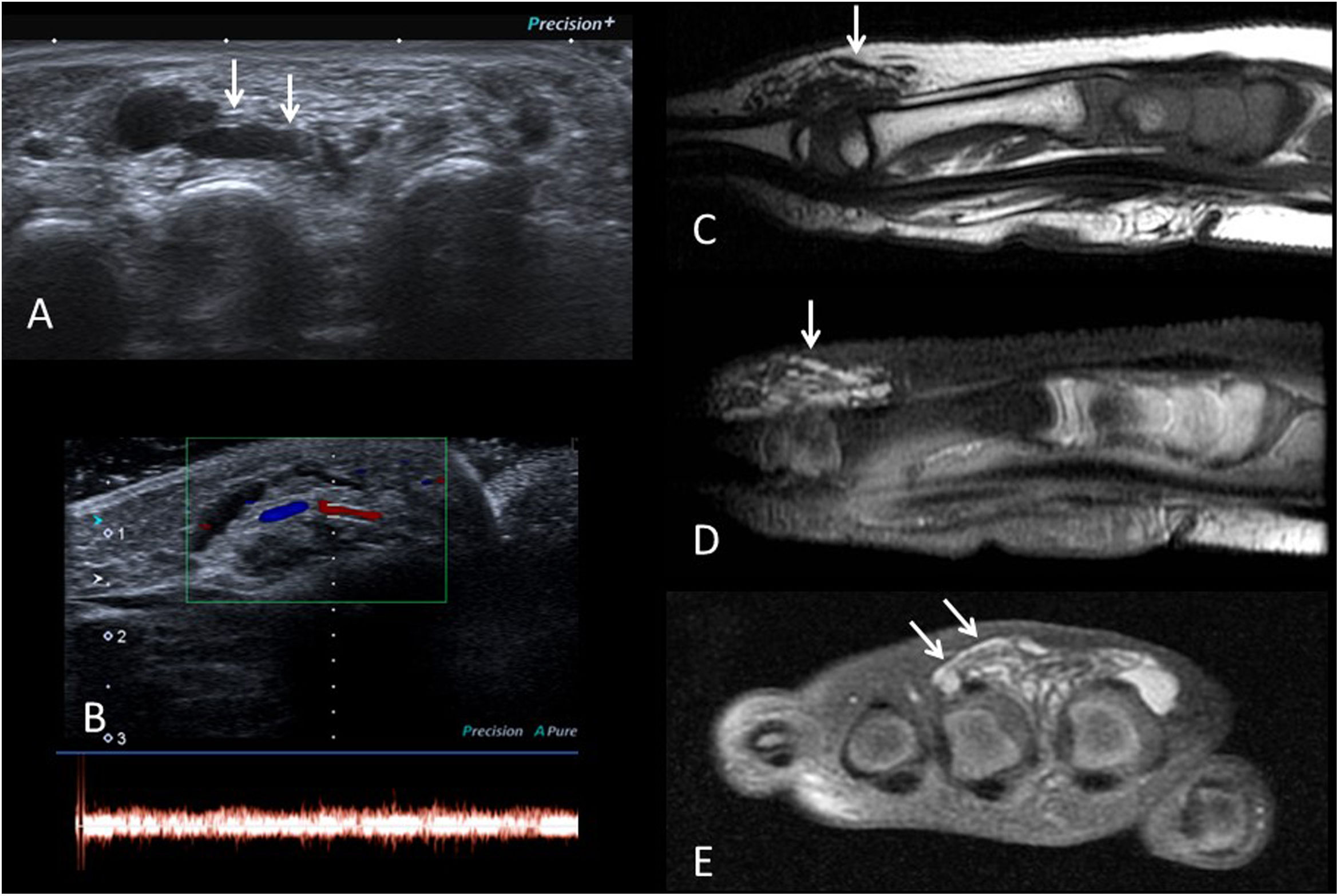

Venous VA on examination are bluish lesions, sometimes difficult to distinguish clinically from deep haemangiomas if no vascular pathways are evident. Vascular pathways can be detected on ultrasound and MRI, with high signal on T2-weighted sequences31 (Fig. 8). Phleboliths may sometimes appear. They can be complicated by thrombosis or bleeding.

Venous-type vascular malformation on the dorsum of the foot of a 10-year-old boy. A) Grey-scale ultrasound showing anechoic vascular pathways (arrows). B) Colour and pulsed Doppler ultrasound images showing venous flow. C) Sagittal T1-weighted MRI image showing hypointense vascular structures (arrow). D and E) T2-weighted MRI images with fat saturation in the sagittal and coronal planes, showing signal hyperintensity of the vascular pathways (arrows), consistent with low-flow vascular malformation.

Arteriovenous VA are less common than simply venous ones. Vascular pathways are also identified, but arterial flow is detected by Doppler ultrasound and no signal in the spin-echo MRI sequences. They can be complicated by thrombosis and bleeding and cause haemodynamic problems due to steal phenomenon.

If the VA is not causing any medical or cosmetic problems, a conservative approach may be reasonable. In superficial capillaries, laser is the usual treatment. The rest can be treated surgically, or more often with interventional vascular radiology techniques. Low-flow malformations are treated with sclerotherapy32,33 and high-flow with embolisation. In low-flow VA which, due to their complexity, are not candidates for surgery or sclerotherapy, there is the alternative of drug treatment with sirolimus34.

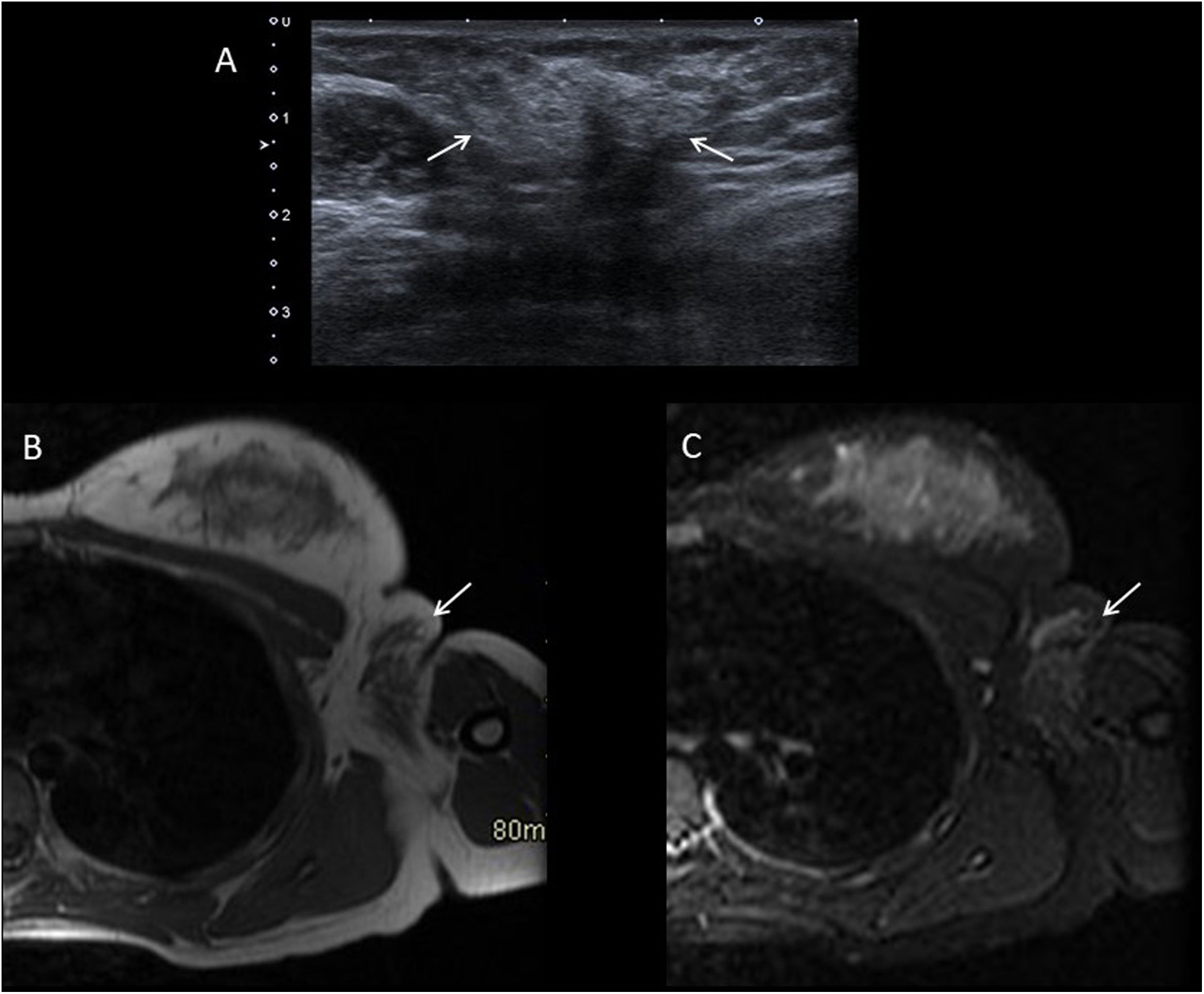

Axillary breast tissueThis occurs in peri-pubertal girls as a sometimes painful mass in their axilla. This diagnosis should be questioned before thelarche. Both ultrasound and MRI show an area with poorly defined borders with echogenicity and an echographic pattern identical to that of the breast tissue35 (Fig. 9).

Fourteen-year-old girl with breast tissue in left axilla. A) Grey-scale ultrasound showing hyperechoic breast glandular tissue in the axilla fat (arrows). B and C) Axial T1-weighted and STIR MRI images, showing that the signal intensity of the ectopic tissue in the axilla (arrows) is identical to that of the breast glandular tissue.

Although very often no treatment is necessary, once the origin of the “mass” has been clarified it can be surgically resected if it causes discomfort.

Subcutaneous granuloma annulareGranuloma annulare is a common non-infectious dermatosis which affects healthy children and young people. It can appear in any part of the body, except for the mucous membranes. The most common location is the back of the hands and feet.

They are self-limiting lesions, although quite persistent, lasting up to several years. Biopsy shows a nonspecific granuloma with a central area of necrotic collagen fibres and a peripheral palisade infiltrate with histiocytes, lymphocytes and giant cells. Its aetiology is unknown.

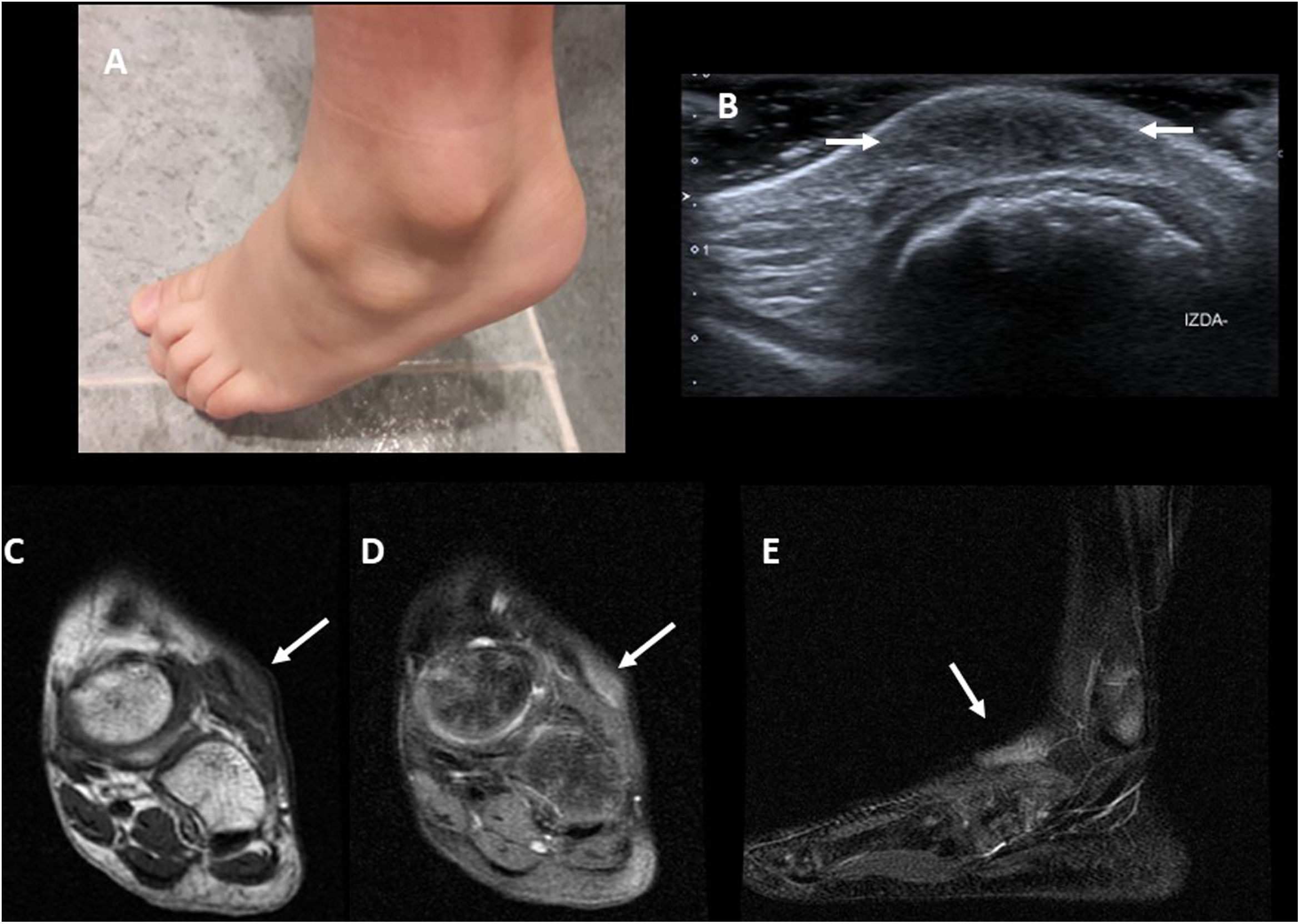

Superficial lesions are usually diagnosed by a dermatologist36 and do not reach the Radiology services, although there is a subcutaneous form which is virtually exclusive to paediatric patients in which painless nodules appear, firm to the touch, but with normal skin appearance (Fig. 10A). Knowledge of granuloma annulare on the part of the radiologist avoids unnecessary biopsies and interventions.

A) Clinical image of a 6-year-old boy with two subcutaneous granuloma annulare lumps on the dorsum of his foot. B) Ultrasound image from the same patient, showing a hypoechoic thickening with poorly defined borders of the subcutaneous cellular tissue (arrows). C) Coronal T1-weighted MRI image from another patient. The lesion (arrow) is hypointense and with poorly defined borders. D and E) T2-weighted MRI images with fat saturation from the same patient. The lesion is hyperintense, with poorly defined borders (arrows).

Ultrasound is the most widely used test due to its availability. The appearance is quite typical, identifying sometimes difficult-to-see hypoechoic areas with imprecise borders in the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 10B) and normally without detectable flow on colour Doppler study37.

On MRI, lesions with poorly defined borders can be seen in the subcutaneous cellular tissue, isointense with muscle on T1- and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences with fat suppression38 (Fig. 10C and D). The presence of enhancement varies greatly. Usually, no biopsy is performed if the lesion is asymptomatic with typical imaging findings. A biopsy will only be taken if the clinical course is not as expected (for example, growth, ulceration or development of local symptoms).

Post-traumatic fat necrosisPost-traumatic fat necrosis is a common cause of subcutaneous nodules in children. They are the result of oedema, haemorrhage, necrosis and fibrosis in different proportions depending on how much time has elapsed39. Very often, the consultation is long after the trauma and the original event is not remembered.

Common sites are those most exposed to trauma, such as the pre-tibial area, buttocks, shoulders, cheeks and forehead. These nodules sometimes develop after injections (for example, vaccinations) or birth trauma in neonates.

They are self-limiting lesions and usually of no importance medically, sometimes leaving a residual depression as a cosmetic sequela due to the loss of subcutaneous cellular tissue. The importance for the radiologist is to recognise them to avoid iatrogenesis.

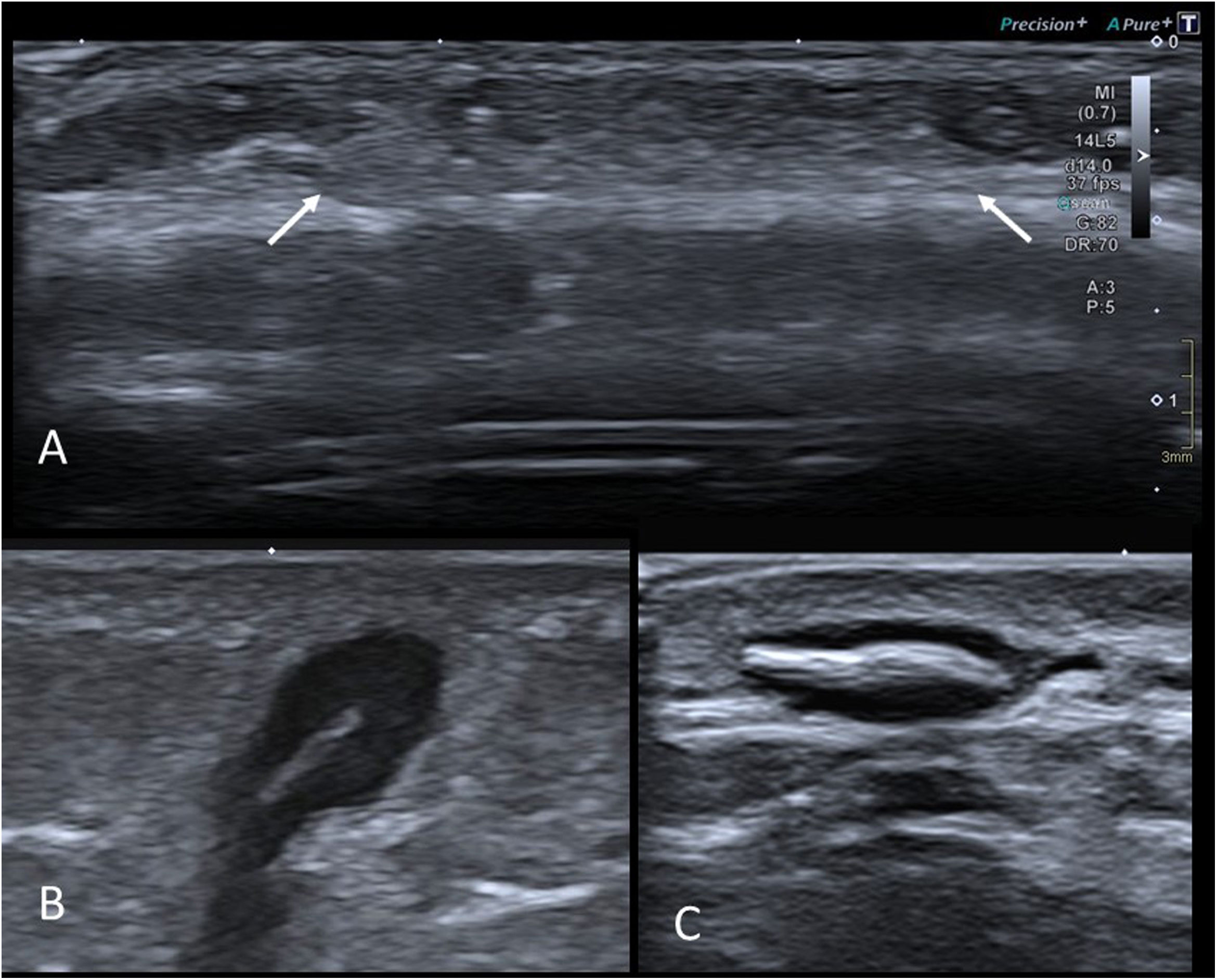

On ultrasound, their appearance varies with the time since the original event. Normally, they are hyperechoic areas with imprecise borders in the subcutaneous cellular tissue (Fig. 11A). The differential diagnosis is with subcutaneous granuloma annulare (which is hypoechoic), and with deep haemangioma, which is usually better defined and presents abundant flow on colour Doppler. Less frequently, liponecrosis appears as an isoechoic nodular lesion in adipose tissue, with a hypoechoic halo40.

A) Ultrasound of the frontal region of an 18-month-old girl with a palpable nodule. History of trauma in the area two months earlier. Hyperechoic area with imprecise borders in the subcutaneous cellular tissue (arrows) consistent with liponecrosis. B) Grey-scale ultrasound image of a foreign body granuloma in the left buttock of a 3-year-old girl. Subcutaneous lesion with a central hyperechoic linear image (which turned out to be a small thorn of plant origin) and a surrounding hypoechoic area corresponding to the granulomatous reaction. C) Grey-scale ultrasound image of a foreign body granuloma on the dorsum of the hand of an 11-year-old boy who had had a splinter. The findings are similar to those in the previous figure.

Relatively often, the cause of a soft tissue nodule in children is the presence of a granulomatous reaction to a foreign body. The sites most exposed to this type of lesion are the feet, knees and buttocks. Very often the patient cannot even recall the original event.

Most of the time, the foreign body is of plant origin (for example, thorns or splinters) and is therefore radiolucent41. Ultrasound is the test of choice42 and the appearance is very typical, with the foreign body appearing as a subcutaneous hyperechoic linear image surrounded by a hypoechoic nodular area, which is the surrounding granulomatous reaction (Fig. 11B and C). Ultrasound may also be helpful in guiding surgical removal43.

ConclusionsPalpable masses are common in children and cover a very wide range of different diseases. The vast majority of lesions are benign in nature.

The imaging test of choice is almost always ultrasound, which apart from being quick and cost-effective, is harmless and does not require sedation.

This article describes the clinical and radiological characteristics of the most common lesions, although it will be followed by a second part which will explain many more. Knowing about them helps us to make the correct diagnosis, without unnecessarily resorting to more invasive tests, and avoiding delays in the care process when we do encounter a more serious disease.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: DL and IP.

- 2

Study conception: DL and IP.

- 3

Study design: DL and IP.

- 4

Data collection: DL and IP.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: DL and IP.

- 6

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7

Literature search: DL and IP.

- 8

Drafting of the article: DL, IP, LC and LA.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: DL, IP, LC, JA and LA.

- 10

Approval of the final version: DL, IP, LC, JA and LA.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.