Osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma are the most frequent malignant bone tumours in children. The aim of this study is to characterize clinical and radiological features at presentation of a large cohort of children with these diseases, radiological findings useful to differentiate them and the main prognostic factors.

Material and methodsRetrospective analysis of clinical and imaging findings of 83 children diagnosed and treated of Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma in a paediatric hospital during a period of 10 years.

ResultsBoth tumours showed aggressive radiological features such as permeative or moth-eaten margins, cortical disruption, discontinuous periosteal reaction, intense contrast uptake, tumoral necrosis and soft-tissue component. They differed in their location, osseous matrix and gender predilection. Osteosarcoma occurred more frequently in the metaphysis of long bones (62%) with a blastic appearance (53%). Ewing sarcoma showed a predilection for male patients (71%), occurred in flat bones (42%) and in the diaphysis of long bones (58%) with a lytic appearance (82%). 29% of children presented with primary metastasis, most frequently located in the lungs. Survival rates were 78% in OS and 76% in Ewing sarcoma. Metastatic disease, aggressive radiological features and low percentage of tumoral necrosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy were associated with poor prognosis (p < 0.05).

ConclusionsImaging can confidently diagnose malignant paediatric bone tumours in children and may differentiate Ewing sarcoma from osteosarcoma, based on gender, location and appearance of the neoplasm. Metastatic disease, presence of aggressive radiological features and low percentage of tumoral necrosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy were associated with poor prognosis.

El osteosarcoma y el sarcoma de Ewing son los tumores óseos más frecuentes en niños. El objetivo de este estudio es describir las características clínicas y radiológicas en el momento de la presentación de una amplia cohorte de niños con estas enfermedades, los hallazgos radiológicos útiles para diferenciarlas y los principales factores pronósticos.

Materiales y métodosAnálisis retrospectivo de los hallazgos clínicos y de imagen de 83 niños diagnosticados y tratados de sarcoma de Ewing y osteosarcoma en un hospital pediátrico durante un periodo de 10 años.

ResultadosAmbos tumores presentaban características radiológicas agresivas como márgenes permeables o apolillados, disrupción cortical, reacción perióstica discontinua, intensa captación de contraste, necrosis tumoral y componente de partes blandas. Se diferenciaban en su localización, matriz ósea y su predilección por sexo. El osteosarcoma se presentó con mayor frecuencia en la metáfisis de los huesos largos (62%) con una apariencia blástica (53%). El sarcoma de Ewing mostró predilección por los pacientes varones (71%), se presentó en los huesos planos (42%) y en la diáfisis de los huesos largos (58%) con una apariencia lítica (82%). El 29% de los niños presentaba metástasis primaria, localizada con mayor frecuencia en los pulmones. Las tasas de supervivencia fueron del 78% en el osteosarcoma y del 76% en el sarcoma de Ewing. La enfermedad metastásica, características radiológicas agresivas y un bajo porcentaje de necrosis tumoral tras la quimioterapia neoadyuvante se asociaron a un mal pronóstico (p < 0,05).

ConclusionesLas técnicas de imagen permiten diagnosticar con seguridad los tumores óseos pediátricos malignos en niños y puede diferenciar el sarcoma de Ewing del osteosarcoma en función del sexo, la localización y la apariencia de la neoplasia. La enfermedad metastásica, la presencia de características radiológicas agresivas y un bajo porcentaje de necrosis tumoral tras la quimioterapia neoadyuvante se asociaron a un mal pronóstico.

Malignant bone tumours represent about 8% of malignant neoplasms in children.1 The most frequent are osteosarcoma (OS) and Ewing sarcoma (ES).2 They are aggressive lesions that tend to metastasize to the lung. Therefore, early diagnosis is essential to improve survival rate.3

Imaging can identify aggressive features in both type of tumours such as bone destruction, periosteal reaction or associated soft tissue mass.4,5 OS and ES may differ in their bone location and radiological pattern, which is important to help distinguishing between them since they differ in their natural history and therapeutical approach.2

Conventional radiographs are the initial imaging modality for the evaluation of these tumours. Computed tomography (CT) is used in specific anatomical areas and to exclude lung metastases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used for determining the local extent of disease.5

The main objectives of this article were to describe radiological features of ES and OS in a large cohort of children and to determine imaging differences between them. Secondly, we analysed the correlation between the presence of aggressive radiological features, metastasis at diagnosis and histological response to neoadjuvant treatment, and the overall survival and event-free survival.

Material and methodsStudy population and outcomes of interestWe retrospectively reviewed cases of children diagnosed with a primary bone tumour (OS or ES) and treated in a third-level paediatric hospital in a 10-year period (from 2011 to 2020, both included). Clinical records, imaging studies archived in PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) and radiological reports were analysed, collecting the following data:

- •

Epidemiological data: gender and age.

- •

Clinical data: type of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and/or hematopoietic stem cell transplant) and survival rates.

- •

Histological diagnosis after biopsy or surgery, and percentage of tumoral necrosis after neoadjuvant treatment. A cut-off of 90% was used to divide patients in good or poor responders.

- •

Radiological features at diagnosis:

- o

Conventional radiographs and CT were reviewed analysing:

▪Tumour location in the skeleton (axial vs appendicular, long vs flat bone) and longitudinal location in the long bones (metaphysis, diaphysis or epiphyses).

▪Radiological pattern: lytic, blastic or mixed. When a blastic matrix was present, the type of mineralization was determined (osteoid vs chondral).

▪Margins: geographic (well-defined with or without sclerotic borders), ill-defined (wide transition zone), moth-eaten or permeative (small, patchy, ill-defined areas of bone lysis with ill-defined margins).

▪Cortical involvement: non-aggressive (hyperostosis, endosteal scalloping or ballooning cortex) or aggressive (cortical disruption).

▪Periosteal reaction: absent, non-aggressive (solid or unilamellated) or aggressive (multilamellated onion-skin reaction or discontinuous multilamellated appearance including spiculated, “hair-on-end”, sunburst and Codman triangle patterns).

- o

MRI before treatment were reviewed analysing:

▪Presence of soft-tissue component/mass.

▪Enhancement pattern: diffuse, heterogenous or peripheral.

▪Epiphyseal involvement in OS.

▪Presence of skip metastasis and/or distant metastasis.

- o

The collected data were analysed with IBM SPSS Statistics v27.0.1.0 Software.

Epidemiological, clinical, histological and radiological outcomes were compared by diagnosis (OS vs ES) using descriptive statistics. Qualitative outcomes (gender, radiological features, tumour necrosis and treatment) are expressed as percentages. Qualitative outcomes (gender, survival time) are expressed as mean and standard deviation.

The outcome cortical reaction was dichotomized into two groups, non-aggressive (hyperostosis, endosteal scalloping and ballooning cortex) and aggressive (cortical disruption). The outcome periosteal reaction was dichotomized into two groups, non-aggressive (no periosteal reaction, solid and unilamellated) and aggressive (multilamellated onion-skin reaction or discontinuous multilamellated appearance including spiculated, “hair-on-end”, sunburst and Codman triangle patterns).

Chi-square test was used to assess the difference for qualitative variables and Student’s t-test for quantitative variables. Due to the small sample size, for some of the dichotomous variables (surgery, radiotherapy, HSCT and skip metastasis) the chi-square test was rejected in favour of the Fisher’s exact test. The same problem occurred for the outcome cortical involvement (initially subdivided into “Absent / Endosteal Scalloping / Insufflation / Hyperostosis / Destruction”) and periosteal reaction (initially subdivided into “Absent / Unilaminar / Continuous / Discontinuous”). It was solved by grouping the data into two subgroups based on their aggressiveness (Aggressive and Non-Aggressive).

The Student's t-test was used to assess the quantitative variable survival time. In the case of outcome age, the non-normality of its distribution in the two groups of patients was verified using Shapiro–Wilk, so the Student's t-test was replaced by the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test.

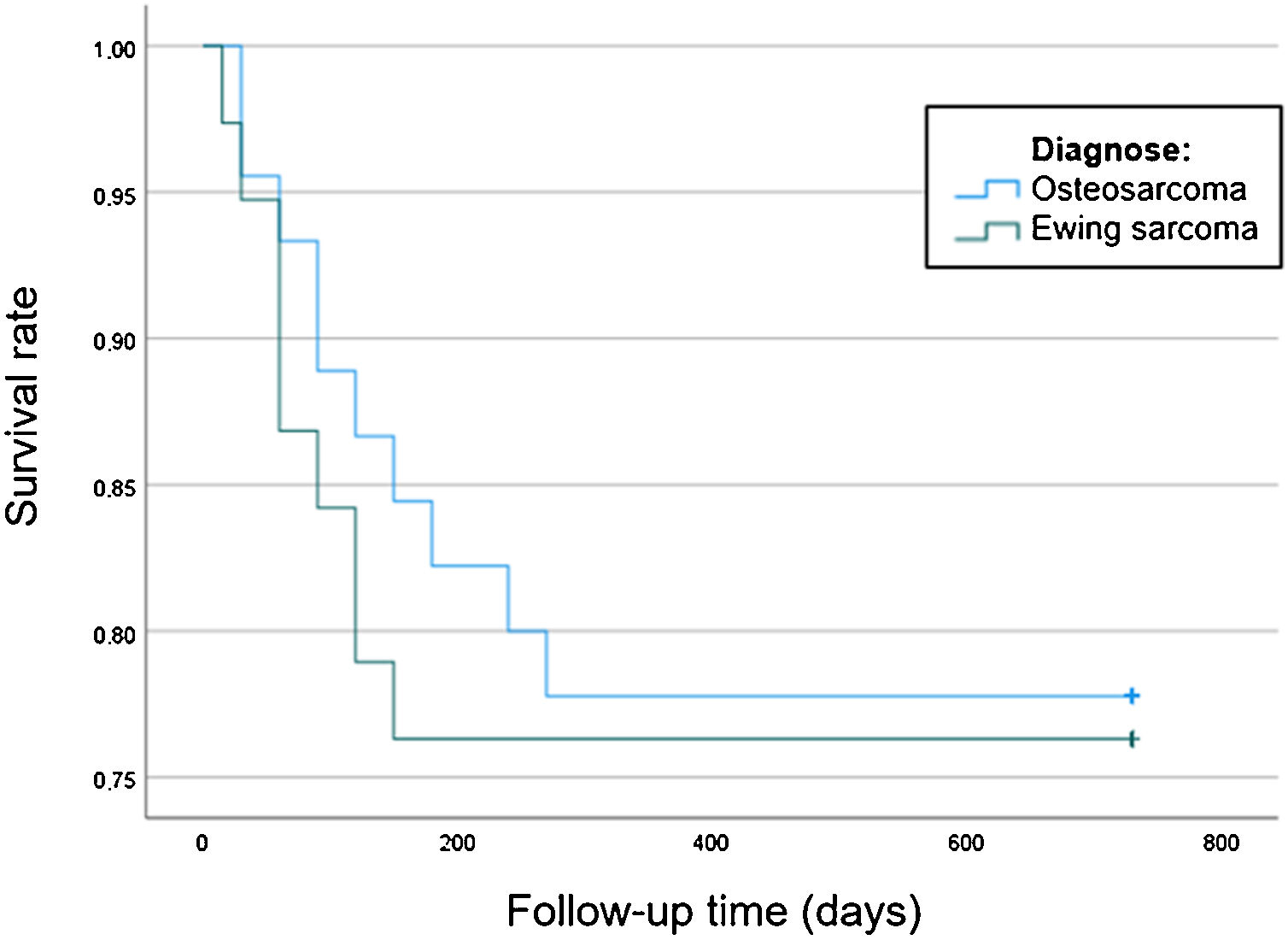

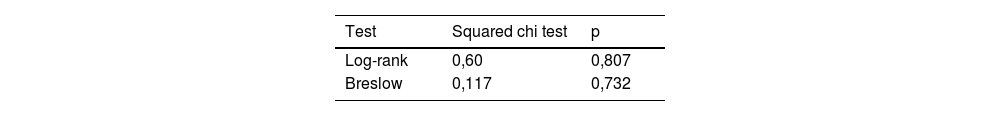

In order to compare the survival between the patients diagnosed with OS and ES, a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed. We compared survival between OS and ES using Log-Rank and Breslow tests (Table 1). In addition, Kaplan Meier curves for both groups were obtained (Fig. 1).

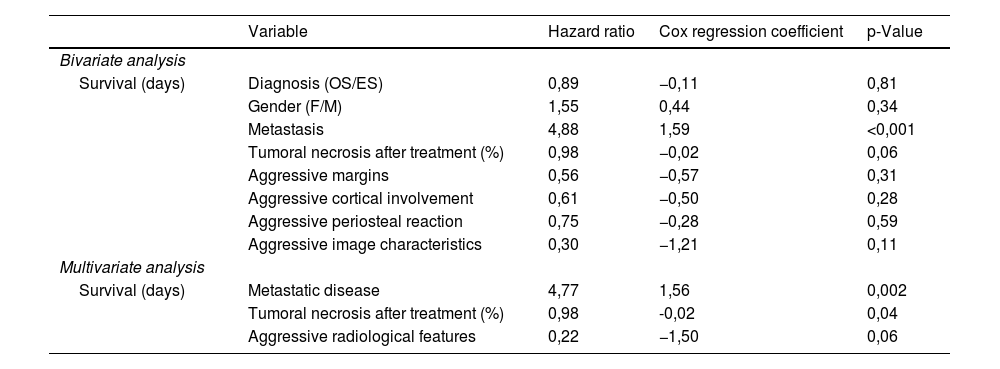

Finally, a bivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between each variable and the outcome survival time. Association between survival time and each of the variables is expressed through a hazard ratio and the Cox regression coefficient. The outcome aggressiveness was created, it includes those patients with aggressive characteristic in at least one of the radiological outcomes (margins, cortical reaction or periosteal reaction). Variables with p < 0,25 in bivariate analysis were included in a multivariable analysis (Table 2). Association between survival time and each of the variables is expressed through a hazard ratio and the Cox regression coefficient. Wald test was used in both cases.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis to estimate the prognostic value/survival of multiple clinical and imaging features of 83 children with osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma.

| Variable | Hazard ratio | Cox regression coefficient | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate analysis | ||||

| Survival (days) | Diagnosis (OS/ES) | 0,89 | −0,11 | 0,81 |

| Gender (F/M) | 1,55 | 0,44 | 0,34 | |

| Metastasis | 4,88 | 1,59 | <0,001 | |

| Tumoral necrosis after treatment (%) | 0,98 | −0,02 | 0,06 | |

| Aggressive margins | 0,56 | −0,57 | 0,31 | |

| Aggressive cortical involvement | 0,61 | −0,50 | 0,28 | |

| Aggressive periosteal reaction | 0,75 | −0,28 | 0,59 | |

| Aggressive image characteristics | 0,30 | −1,21 | 0,11 | |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Survival (days) | Metastatic disease | 4,77 | 1,56 | 0,002 |

| Tumoral necrosis after treatment (%) | 0,98 | -0,02 | 0,04 | |

| Aggressive radiological features | 0,22 | −1,50 | 0,06 | |

p-values < 0,05 were considered significant in all cases.

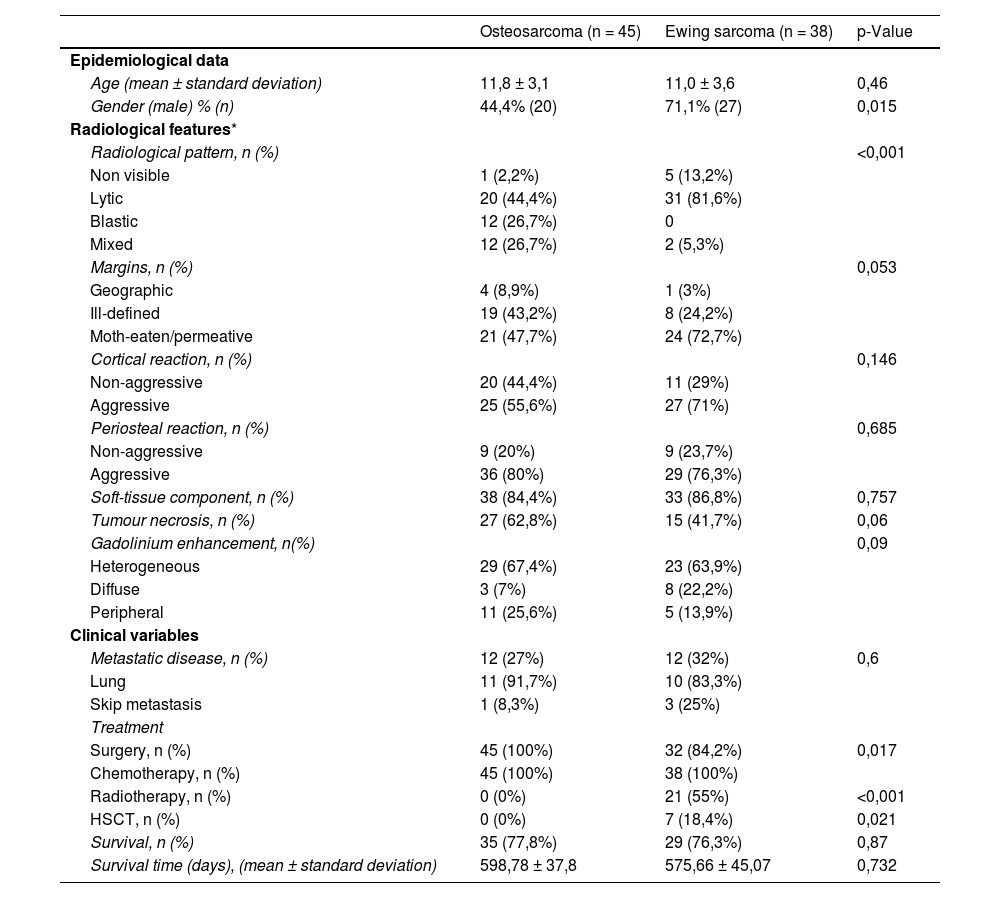

Results83 paediatric patients (47 boys, 36 girls) were diagnosed of a primary bone tumour in our hospital in a period of 10 years (2011–2020). 45 of them had OS and 38 ES. Table 3 lists epidemiological, clinical and radiological data of the study cohort.

Clinical, pathologic and radiological characteristics of 83 children with Ewing sarcoma or osteosarcoma.

| Osteosarcoma (n = 45) | Ewing sarcoma (n = 38) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiological data | |||

| Age (mean ± standard deviation) | 11,8 ± 3,1 | 11,0 ± 3,6 | 0,46 |

| Gender (male) % (n) | 44,4% (20) | 71,1% (27) | 0,015 |

| Radiological features* | |||

| Radiological pattern, n (%) | <0,001 | ||

| Non visible | 1 (2,2%) | 5 (13,2%) | |

| Lytic | 20 (44,4%) | 31 (81,6%) | |

| Blastic | 12 (26,7%) | 0 | |

| Mixed | 12 (26,7%) | 2 (5,3%) | |

| Margins, n (%) | 0,053 | ||

| Geographic | 4 (8,9%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Ill-defined | 19 (43,2%) | 8 (24,2%) | |

| Moth-eaten/permeative | 21 (47,7%) | 24 (72,7%) | |

| Cortical reaction, n (%) | 0,146 | ||

| Non-aggressive | 20 (44,4%) | 11 (29%) | |

| Aggressive | 25 (55,6%) | 27 (71%) | |

| Periosteal reaction, n (%) | 0,685 | ||

| Non-aggressive | 9 (20%) | 9 (23,7%) | |

| Aggressive | 36 (80%) | 29 (76,3%) | |

| Soft-tissue component, n (%) | 38 (84,4%) | 33 (86,8%) | 0,757 |

| Tumour necrosis, n (%) | 27 (62,8%) | 15 (41,7%) | 0,06 |

| Gadolinium enhancement, n(%) | 0,09 | ||

| Heterogeneous | 29 (67,4%) | 23 (63,9%) | |

| Diffuse | 3 (7%) | 8 (22,2%) | |

| Peripheral | 11 (25,6%) | 5 (13,9%) | |

| Clinical variables | |||

| Metastatic disease, n (%) | 12 (27%) | 12 (32%) | 0,6 |

| Lung | 11 (91,7%) | 10 (83,3%) | |

| Skip metastasis | 1 (8,3%) | 3 (25%) | |

| Treatment | |||

| Surgery, n (%) | 45 (100%) | 32 (84,2%) | 0,017 |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | 45 (100%) | 38 (100%) | |

| Radiotherapy, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (55%) | <0,001 |

| HSCT, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (18,4%) | 0,021 |

| Survival, n (%) | 35 (77,8%) | 29 (76,3%) | 0,87 |

| Survival time (days), (mean ± standard deviation) | 598,78 ± 37,8 | 575,66 ± 45,07 | 0,732 |

HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

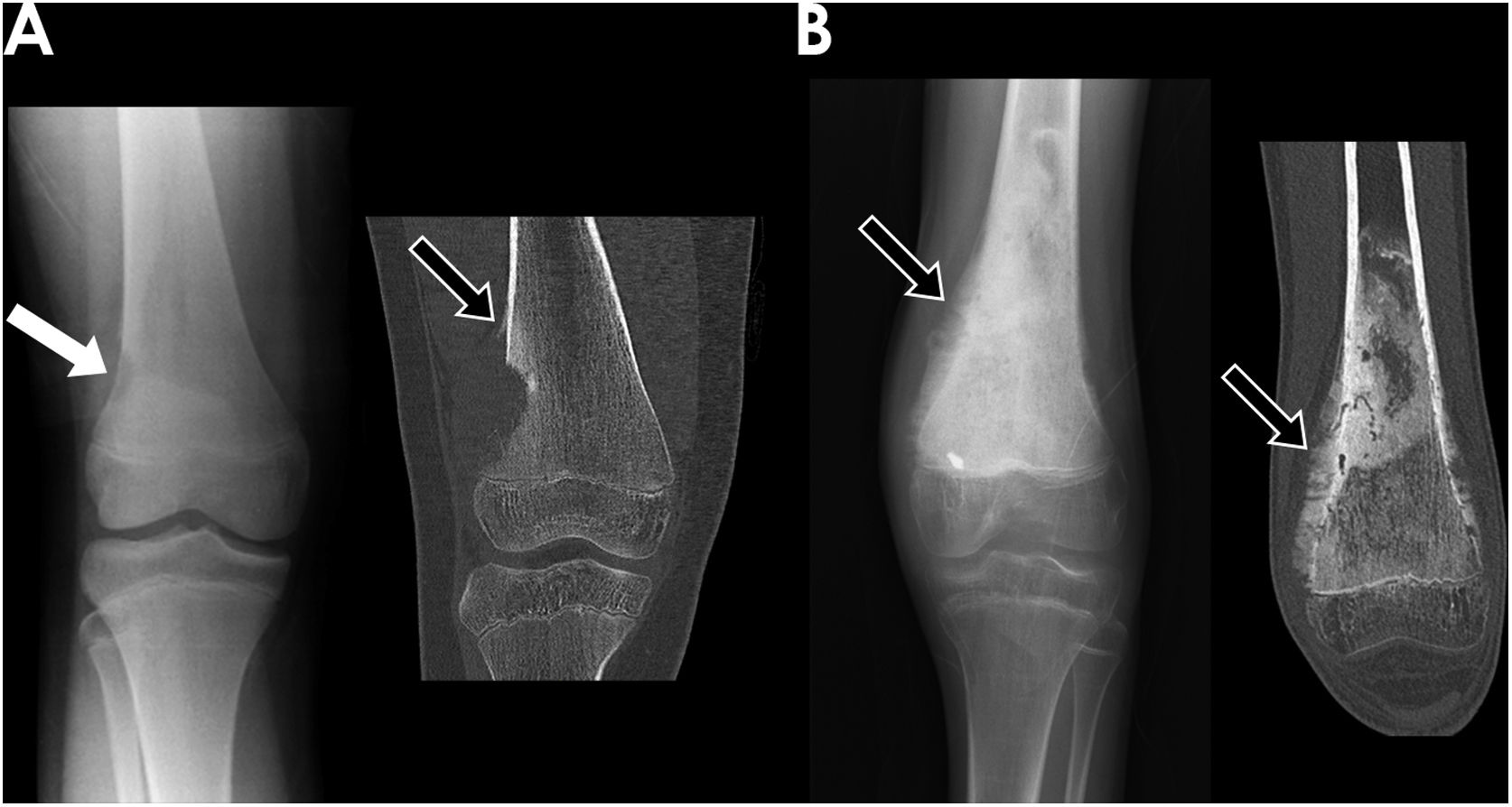

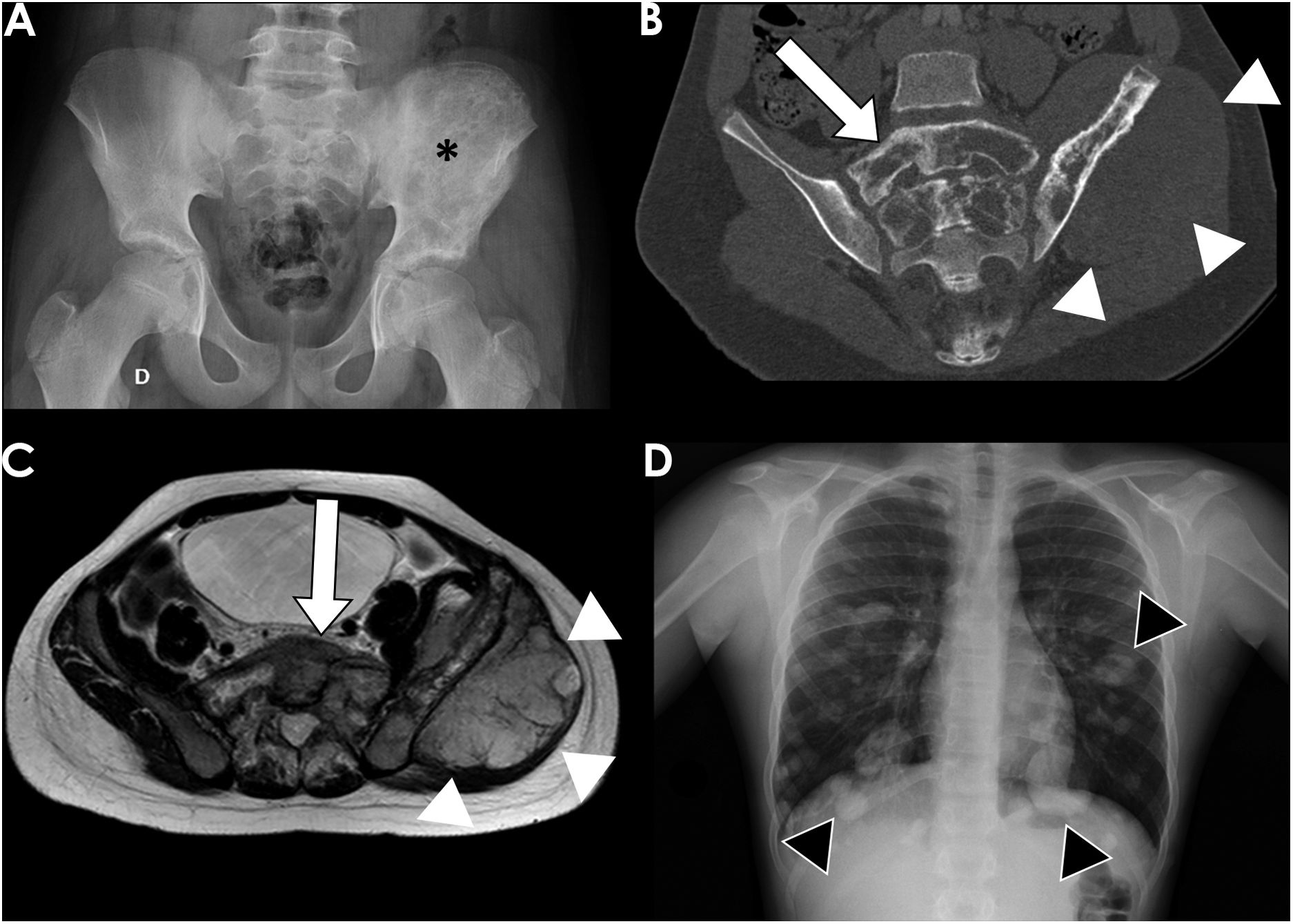

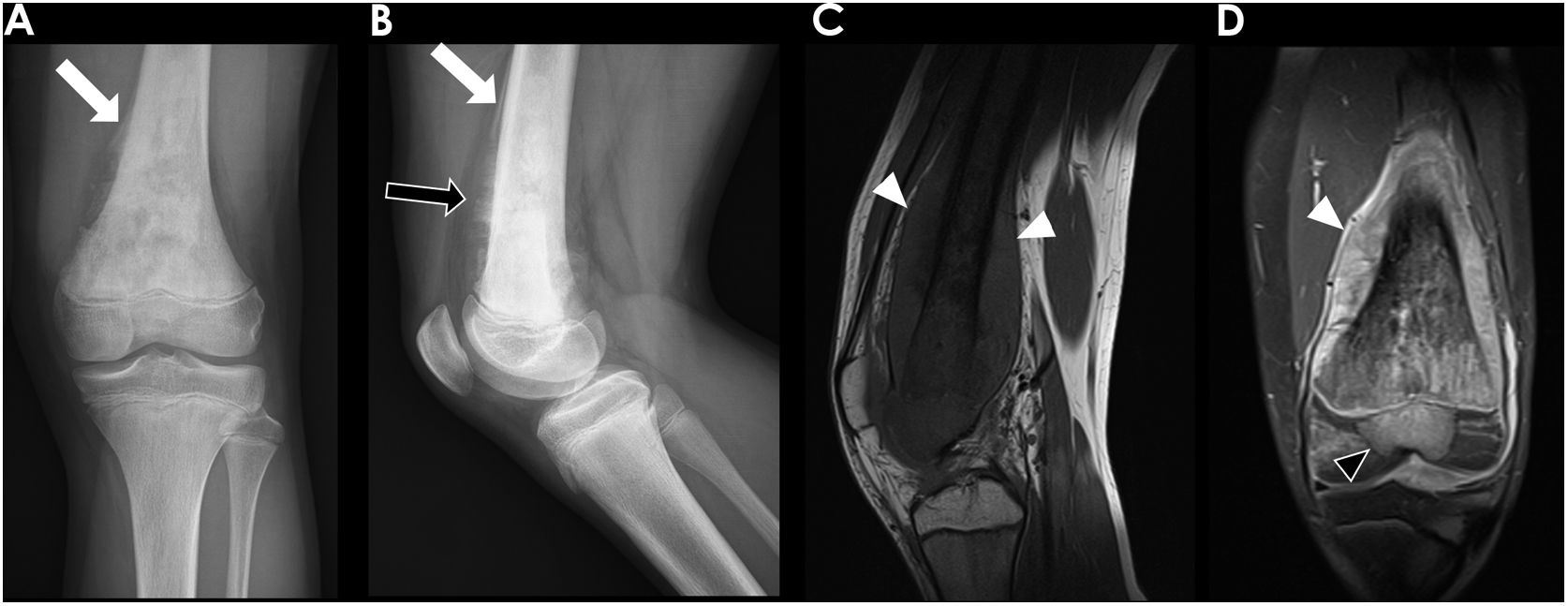

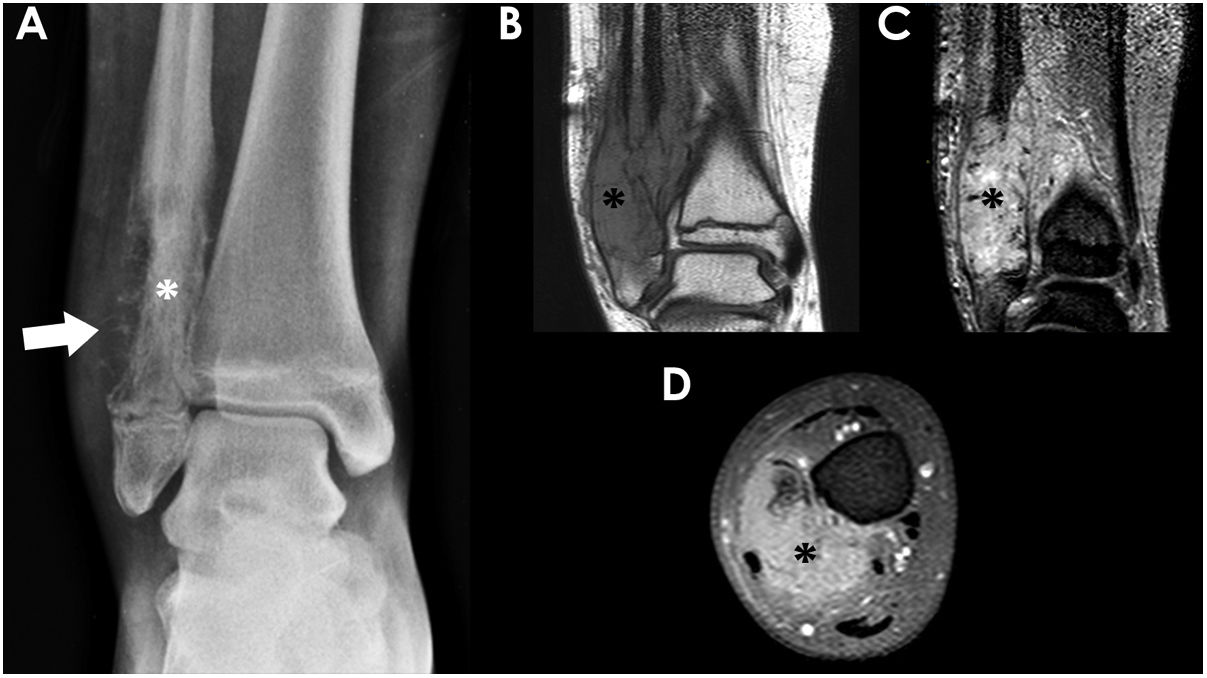

All OS were located in long bones. The most frequently affected bones were the distal femur (56%) (Fig. 2), proximal tibia (20%), proximal humerus (13%) and distal radius (2%). ES affected long bones (55%) (proximal femur 24%, tibia 16%, fibula 13% and radius 3%) and the axial skeleton (ilium 18% (Fig. 3), sacrum 11%, ribs 5%, ischium 3% and pubis 3%). Less common locations were right mandibular ramus, and left calcaneus.

A) Frontal radiography and coronal CT reconstruction of a 11-year-old girl with osteosarcoma (OS) located in the lateral aspect of the metaphysis of the distal right femur. It appeared as an eccentric lytic lesion with well-defined margins (white arrow), cortical disruption, aggressive periosteal reaction (Codman triangle) (black arrow) and soft-tissue mass component. B) Frontal radiography and coronal CT reconstruction images of a 14-year-old boy with OS located in the metaphysis of left distal femur. The lesion showed a blastic pattern with osteoid mineralization and “hair-on-end” periosteal reaction (black arrows).

12-year-old boy with Ewing sarcoma of the left iliac bone. Frontal radiograph of the pelvis (A) showed an extensive permeative lesion in the left ilium (black asterisk). Coronal CT reconstruction (B) delineated better the tumour, its extension to the sacrum (white arrow) and the associated soft-tissue mass (white arrowheads), which is also shown on the MRI axial T2 image (C). Frontal posteroanterior chest radiograph (D) demonstrated the presence of bilateral lung metastasis (black arrowheads).

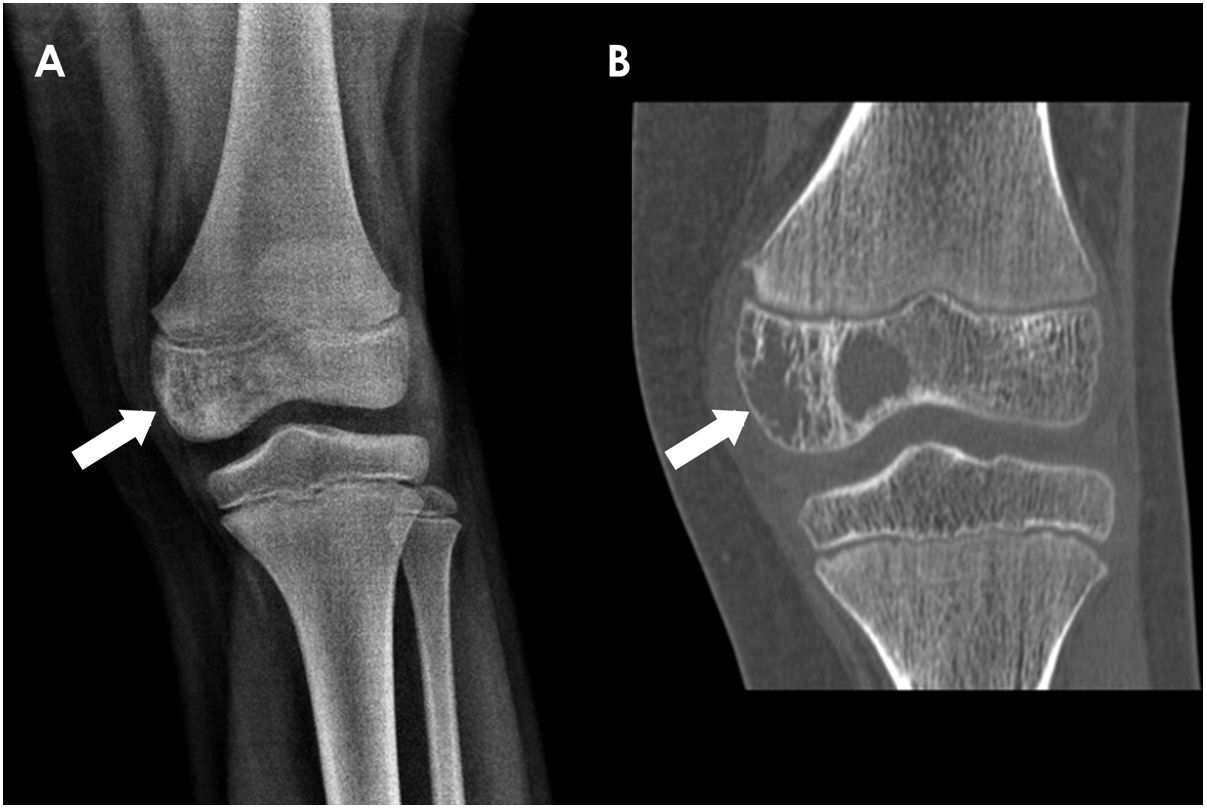

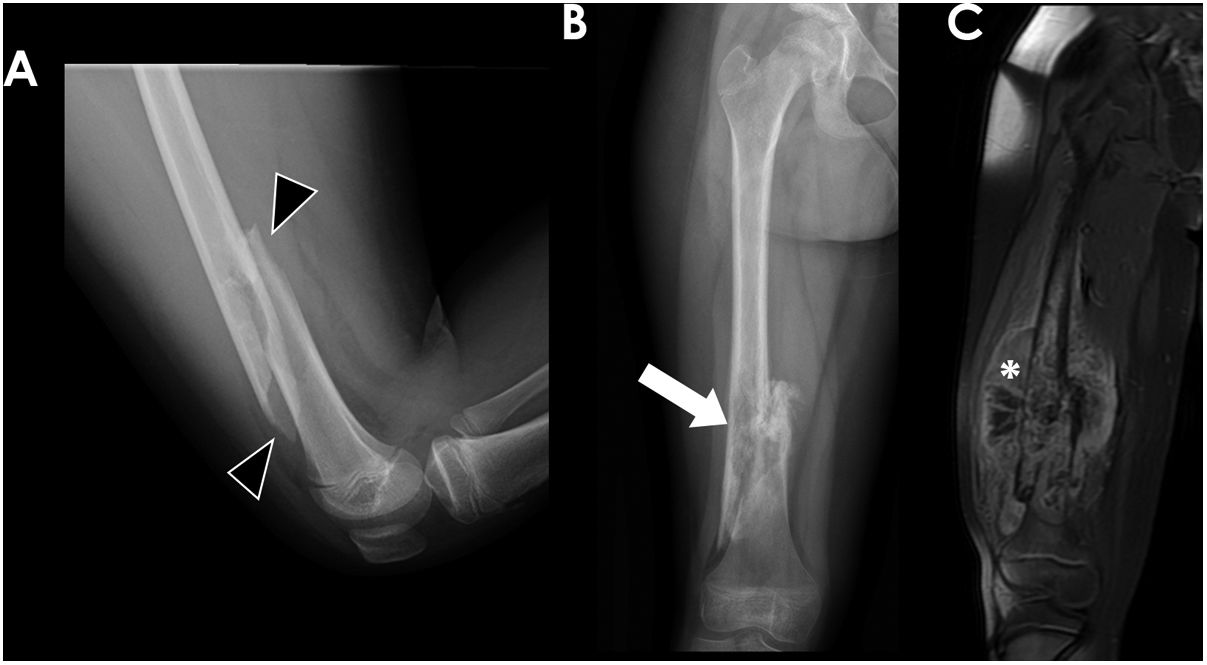

Long bone tumours can be classified according to the longitudinal location inside the bone in epiphyseal, metaphyseal or diaphyseal. In our group of children, most OS were localized in the metaphysis (62%) (Fig. 2), while the majority of ES originated in the diaphysis (52,4%). Epiphyseal origin of these tumours is rare. Nonetheless, we found 2 cases (9,5%) of epiphyseal ES in our group (Fig. 4). In the case of OS, it may affect the epiphyses when it extends directly from the metaphyseal region, across the physis, as it occurred in 5 children of our group (Fig. 5).

13-year-old-boy with osteosarcoma originated in the distal metaphysis of the left femur. Frontal and lateral radiographs (A and B respectively) demonstrated an aggressive metaphyseal lesion with osteoid blastic pattern, and “hair-on-end” (black arrow) and Codman-triangle (white arrows) aggressive periosteal reaction. Sagittal T1 MR image (C) and coronal T1 MR image with fat suppression after gadolinium administration (D) demonstrated a large soft-tissue component (white arrowheads) and the tumoral extension through the physis to the epiphysis (black arrowhead).

Bone lesions were initially assessed with conventional radiographs. Subsequently, MRI was performed to evaluate tumour extension. In some cases, CT or ultrasound (US) were required to evaluate specific features of the lesions (Table 3).

Metastasis, treatment and survivalThe presence of metastasis at diagnosis was seen in 24 children (Table 3).

Treatment consisted of a combination of systemic (chemotherapy) and local therapy (surgery and/or radiotherapy) (Table 3). The mean percentage of tumoral necrosis after treatment was 82% (SD: 20%) in OS and 87% (SD: 20%) in ES. 6 children with ES could not undergo surgery due to the location of the tumour in the axial skeleton and/or the presence of distant metastases.

Nineteen children died, 10 with OS and 9 with ES. The mean survival time at the time of this study was 20 months. No statistical differences were found in survival rates between OS and ES (Table 1). In the survival rate graph, it can be observed that in both tumours the mortality rate increased in the first year until stabilizing around a survival of 76% at 150 days for ES and 78% at 270 days for OS (Fig. 1).

Metastatic disease, low percentage of tumoral necrosis and aggressive radiological features were associated with a worse prognosis (Table 2).

Statistical association was found between the presence of metastasis at diagnosis and a lower overall survival (p = 0,002). It was almost 5 times more frequent the event “death” per time unit in patients with metastasis at diagnosis. A high percentage of tumoral necrosis after neoadjuvant treatment was also associated with higher survival rates (p = 0,037). The association between aggressive radiological features and lower survival rates was close to statistical significance (p = 0,057).

DiscussionMalignant primary bone tumours account for 8% of all paediatric malignancies.1 The two most frequent bone sarcomas in paediatric population are OS (55%) and ES (35%).6 OS has a bimodal age distribution which peaks in early adolescence (15–29 years) and over the age of 65.7 ES is most frequently seen in patients with 4–25 years of age.7 In the literature, both tumours show a male predominance, with a male-to-female ratios of 1.2 in OS and 1.1 in ES.6 In our cohort of patients with OS, there was a female predominance that might be explained by the relatively small sample group and the inclusion criteria (children until 14 years old).

LocationPrimary bone tumours often occur in a characteristic location in the skeleton.8,9 OS has a predilection for sites of rapid bone growth such as the metaphyseal regions,10 whereas ES tends to follow the distribution of red marrow, predominantly in the diaphyseal region of long bones and the axial skeleton.2 Although OS more frequently affects long bones, it can also affect flat bones (20% of cases) such as the pelvis, facial bones or spine.4,11 Our cohort of patients confirmed these findings. However, in our cohort all OS were located in long bones, probably due to the relatively small sample.

Imaging findingsImaging plays a key role in establishing the initial diagnosis of bone tumours and subsequently guiding management.5 Conventional radiographs are the initial imaging modality for its evaluation,12 allowing the classification of the lesion as aggressive or non-aggressive by analysing some imaging characteristics such as margins, cortical expansion or periosteal reaction.5,8

Tumoral margins and the zone of transition between a lesion and adjacent bone are key factors in determining the aggressiveness of a lesion, since they are indicators of the growth rate of the lesion.5,8 Well-defined sharped margins, with or without sclerotic rim, indicate a slow growth rate and, thus, appear in non-aggressive lesions. In contrast, ill-defined, moth-eaten or permeative margins appear in aggressive fast-growing tumours.5 In our group of patients, permeative lytic pattern was most frequent in children with ES, probably due to its origin and dissemination through the red bone marrow (Fig. 6). On the contrary, blastic pattern was more common in OS owing to its mesenchymal origin with osteoblastic differentiation that leads to bone neoformation.

14-year-old boy with Ewing sarcoma located in the distal metaphysis of the right fibula. Frontal radiograph of the ankle (A) showed a lytic lesion with extensive cortical disruption (white asterisk) and aggressive periosteal reaction (white arrow). Coronal T1 (B) coronal fat-suppressed T2 (C) and axial fat-suppressed T1 post-contrast MR images (D) showed the presence of associated soft-tissue component with avid contrast uptake (black asterisks).

Cortical involvement also reflects the growth rate of a lesion. When a slow-growing medullary lesion expands, it causes erosion of the inner surface of the cortex leading to insufflation or endosteal scalloping. In aggressive lesions, the fast growth rate does not allow bone regeneration and may lead to its disruption.8

Finally, periosteal reaction is a less specific feature of a bone lesion nature.5 Solid or unilamellated periosteal reaction are nonaggressive appearances that indicate a slow growing lesion that gives the bone a chance to wall the lesion off. A multilamellated or onionskin pattern are intermediate patterns. Aggressive lesions usually show discontinuous periosteal reaction such as spiculated, hair-on-end or sunburst, or Codman triangle patterns.8 In our group, most of the lesions showed aggressive periosteal reaction, with no differences between OS and ES.

MRI of primary bone tumours is mandatory in their evaluation to determine the stage and as surgery planning,6,10 although some tumours require the use of CT instead of MRI due to its location in complex bones, vertebrae or craniofacial bones.10

MRI protocol should include T1 weighted image (T1WI), short tau inversion recovery (STIR)/fat suppressed T2 weighted image (T2WI), diffusion weighted image (DWI) and post-contrast fat suppressed T1WI.6 MRI provides information about tumoral matrix, its local extension, and evaluation of the response to treatment.10

Assessment of local tumoral extension is of special importance to guide surgical procedures, especially the identification of epiphyseal spread across the physis.13 T1WI gives the best anatomic definition of bone marrow invasion to determine the size of the lesion.14 By contrast, fat-saturated T2WI or STIR sequences may give a falsely increased lesion size since they boost the signal produced by peritumoral oedema.14

MRI also permits the evaluation of the presence and extension of associated soft-tissue mass, which is an indicator of biological aggressiveness (Fig. 7). It is more frequent and voluminous in ES tumours, but occasionally OS may show a large soft-tissue component that makes them difficult to differentiate. This soft-tissue mass usually expands and disrupts the cortical bone, but occasionally in cases of ES, it may extend through the Haversian canals and do not cause cortical disruption.15

10-year-old girl with conventional osteosarcoma of the right distal femur who presented with a pathological fracture. Lateral radiograph of the femur (A) showed a spiroid diaphyseal fracture (black arrowheads). Frontal radiograph performed 3 months later (B) showed poor fracture consolidation and the presence of an underlying permeative lesion with aggressive periosteal reaction (white arrow). Coronal fat-suppressed T1 post-contrast MR image (C) delineated the tumour, with heterogeneous intensity and a voluminous soft-tissue component (white asterisk).

The long-axis field of view should cover the entire affected bone and adjacent joints for proper evaluation of skip metastasis,6 which are small synchronous lesions located within the same bone but separated from the primary tumour by intervening normal marrow.10,16

MRI is also useful in the assessment of tumour response to neoadjuvant treatment,6,10 since itis the primary prognostic factor in OS and ES (tumour necrosis higher than 90% correlates with a better outcome).6 Morphologic changes may occur after neoadjuvancy, mainly reduction of tumoral volume, but this does not always correlate with necrosis percentage.6 Functional MRI with DWI and ADC maps and dynamic contrast-enhanced sequences are imaging tools for non-invasive assessment of primary tumour response.6

Both ES and OS demonstrate aggressive findings reflecting their grade of malignancy and show some overlapping imaging features that difficult the discrimination between both tumours.7 We have not found statistically significant differences on the imaging features between OS and ES (p > 0,05), apart from location. Recent studies have analysed DWI of both tumours and have found significant differences in apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values of ES (0,6 – 0,8 × 10−3 mm2/s) and OS (1,2–1,5 × 10−3 mm2/s),7 which may be a useful tool in challenging cases with overlapping imaging features. We could not asses tumoral ADC values in our group of patients, since DWI was not routinely included in our MR protocol at the beginning of the study.

Metastatic diseaseNearly 10–20% of the patients with a malignant bone tumour are affected by metastatic disease,17 the most common site being the lungs (85%), followed by bone marrow (8–10%) and, occasionally, lymph nodes.10 Metastatic disease is a clear indicator of poor prognosis16 as stated in our group, in which the survival rates were 5 times lower in patients with metastasis.

Whole body imaging may be performed by using fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) to detect metastatic spread.6 Whole-body MRI is a promising technique for whole-body evaluation for extrapulmonary metastases, but has not been investigated or validated in OS or ES to the same extent as FDG PET.6

As the most frequent location of metastasis are the lungs, a chest CT is mandatory at an early stage to assess the presence of pulmonary metastasis,6,10 as well as to evaluate their number and distribution as they are important prognostic factors.11 Generally, any lung lesion larger than 10 mm or multiple lesions (3 or more) larger than 5 mm are considered evidence of metastasis.11 The addition of maximum-intensity projection (MIP) images improves the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of CT for detection of pulmonary metastases.6 Unfortunately, the number of CT-determined pulmonary nodules correlates poorly with the number detected in surgery and rarely the CT characteristics of these nodules are definitive for metastatic disease.13 Thus, histologic diagnosis is frequently required as the presence of lung metastases elevates disease, using CT in these cases to guide surgical biopsy.13

Skip lesions represent embolic micrometastasis within bone marrow sinusoids of the same bone that are discontinuous from the primary tumour. They are considered local tumoral disease, and may occur across the joint adjacent to the primary tumour (transarticular skip metastasis).13 Though rare (being more frequent in OS than in ES), skip metastasis usually present in high-grade sarcomas and impart a significantly worse patient outcome, needing modification of the surgical procedure since in these cases a limb-sparing procedure may not be performed.2,13

TreatmentThe current standard treatment for OS consists of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy.2,9 The 5-year survival of OS has been between 70%–80% in the last 40 years. New chemotherapeutic drugs tailored to the patient, tumour and genetic features are expected to improve survival in the future.9 Surgery is essential to achieving local control of the disease.9 Nowadays, a limb-sparing surgery is preferred when possible, and amputation is used only in selected cases.11 Even in the absence of detectable metastasis, it is assumed that most OS are micrometastatic at the time of diagnosis, which requires a systemic therapy.9 The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has become the standard protocol of treatment for optimal outcomes since it reduces tumoral size and potential micrometastasis, permits limb salvage surgeries, and reduces recurrence rates.10,18 Local radiotherapy is a second-choice treatment due to the resistance of OS to ionizing radiation.10 It can be considered in advanced disease or axial tumours as a palliative treatment.9,19 External irradiation along with systemic therapy may act as a successful approach toward local control and symptom relief.10 ES management usually includes a combined systemic (chemotherapy) and local (radiotherapy and/or surgery) treatment.2 Chemotherapy is mandatory due to the disseminated nature of this tumour.17 Local therapy is highly individualized and the optimal approach is influenced by multitude factors (patient age, tumour location, size and local extension).16,17,20 Surgical resection of the lesion is preferred when negative surgical margins are possible with acceptable morbidity. Radiation can provide equally durable local control, but carry associated long-term risk of secondary malignancies. However, if surgery would cause excess morbidity, radiotherapy can provide similar treatment outcomes.20

PrognosisIn our study the overall survival rate was 78% in OS and 76% with a mean survival time of 20 months, which are results concordant with the literature. Several prognostic factors have been described including tumour size, good response to chemotherapy and metastasis at diagnosis.17,21,22

Recent therapeutic advances have improved the overall survival of these children. Chemotherapy-induced necrosis has been shown to be a strong prognostic factor in patients with primary bone tumours.2,9,19,23 Good histologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is defined as less than 10% viable tumour cells at the time of surgery.9 Those patients with a higher degree of tumour necrosis at histologic examination have a higher rate of overall survival.2,9,17,19 Our results are consistent with previous studies and tumoral necrosis induced by neoadjuvant treatment correlated with patient outcome.

Metastatic disease at diagnosis is associated with significantly decreased survival rates.21 In the present study, the incidence of metastasis was 27% for OS and 32% for ES and was confirmed as an independent prognostic factor of reduced survival (p = 0,002).

LimitationsSome limitations of the present study are the retrospective nature of the study alongside being a single-centre experience. Moreover, the children included in the study were from different geographical locations in the country, some of them from other sanitary districts, which made it difficult to obtain some clinical data and follow-up information. Imaging studies were acquired during a period of ten years, hence there were some variations in MRI quality and protocols with time. Diffusion-weighted imaging and MR perfusion techniques were not obtained in all studies. Therefore, we could not evaluate them for this study. We also have not evaluated the use of PET-CT in these pathologies in order to limit the extension of the article.

ConclusionThis study has shown that imaging plays a crucial role in the initial diagnosis of osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma in children. Osteosarcoma affects long bone metaphysis with a blastic appearance, while Ewing sarcoma affects flat bones and long bones diaphysis with a lytic pattern. Overall survival was almost 80%, similar in both tumours. Presence of aggressive radiological features, metastasis at diagnosis and absence of chemotherapy induced necrosis correlated with a poorer outcome.

FundingNo public or commercial funding was obtained for the elaboration of this study.

Authorship1. Responsible for study integrity: CMR

2. Study conception: CMR, MBG, JIGC, PCD

3. Study design: CMR, PCD

4. Data acquisition: CMR, MBG, JIGC, PCD

5. Data analysis and interpretation: CMR, MBG, JIGC, PCD

6. Statistical processing: MBG

7. Literature search: CMR

8. Drafting of the manuscript: CMR, MBG

9. Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: PCD, JIGC

10. Approval of the final version: CMR, MBG, PCD

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.