Generalized lymphatic anomaly (GLA) is an uncommon congenital disease secondary to the proliferation of lymphatic vessels in any organ except the central nervous system. GLA has a wide spectrum of clinical and radiological presentations, among which osteolytic lesions are the most widespread, being the ribs the most commonly affected bone. GLA is diagnosed mainly in children and young adults; nevertheless, on rare occasions it can remain asymptomatic and be detected incidentally in older patients. We present an unusual case of GLA in an asymptomatic 54-year-old man who had atypically distributed, purely cystic bone lesions on CT; measuring the Hounsfield (HU) of these lesions enabled us to suspect GLA. This suspicion was confirmed with MRI, PET/CT, CT-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy, and fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous vertebral biopsy. After surgical resection of one of the lesions, histologic study provided the definitive diagnosis.

La anomalía linfática generalizada (ALG) es una enfermedad congénita poco frecuente, secundaria a la proliferación de vasos linfáticos en cualquier órgano a excepción del sistema nervioso central, mostrando un amplio abanico de formas de presentación clínicas y radiológicas, donde las lesiones osteolíticas son la principal constante, siendo las costillas el hueso más frecuentemente afectado. Se diagnostica principalmente en niños y adultos jóvenes; no obstante, en raras ocasiones la enfermedad puede ser asintomática y detectarse de forma incidental en pacientes de mayor edad. Presentamos un caso inusual de ALG en un paciente de 54 años, asintomático y con presencia de lesiones óseas de distribución atípica en la tomografía computarizada (TC) donde la naturaleza puramente quística de las lesiones, evidenciada mediante la medición de las unidades Hounsfield, permitió establecer el diagnóstico de sospecha de ALG, que posteriormente se confirmó con resonancia magnética, tomografía por emisión de positrones/TC, punción aspiración con aguja fina guiada por TC y biopsia vertebral percutánea con guía fluoroscópica. Finalmente, se obtuvo el diagnóstico anatomopatológico definitivo tras la resección quirúrgica de una de las lesiones.

Generalised lymphatic anomaly (GLA), previously known as lymphangiomatosis or cystic angiomatosis, is a type of complex lymphatic anomaly (CLA)1 consisting of a non-neoplastic congenital malformation secondary to abnormal proliferation of lymphatic vessels. It can develop in any organ, apart from the central nervous system.2 This rare condition, the incidence of which is unknown, usually affects children or young adults before the age of 20.3 The most common finding is osteolytic lesions, which are hypodense on computed tomography (CT) and hyperintense on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences, very often along with visceral, peritoneal or thoracic lymphangiomas.1–3 The ribs tend to be affected and, according to most authors, this is the most common bony location.4,5

We present a case of GLA as an incidental finding in a CT scan performed in our Accident and Emergency Department on an asymptomatic middle-aged patient with polyostotic, mediastinal and retroperitoneal disease, without rib involvement, in whom the cystic nature of the bone lesions measured by Hounsfield units (HU) led to the suspected diagnosis, which was subsequently confirmed by other imaging techniques and invasive and surgical procedures.

Case reportThis was a 54-year-old male, with no relevant medical history, who attended Accident and Emergency with clinical signs suggestive of acute aortic syndrome and hypertensive crisis, for which an urgent CT angiogram of chest, abdomen and pelvis was requested.

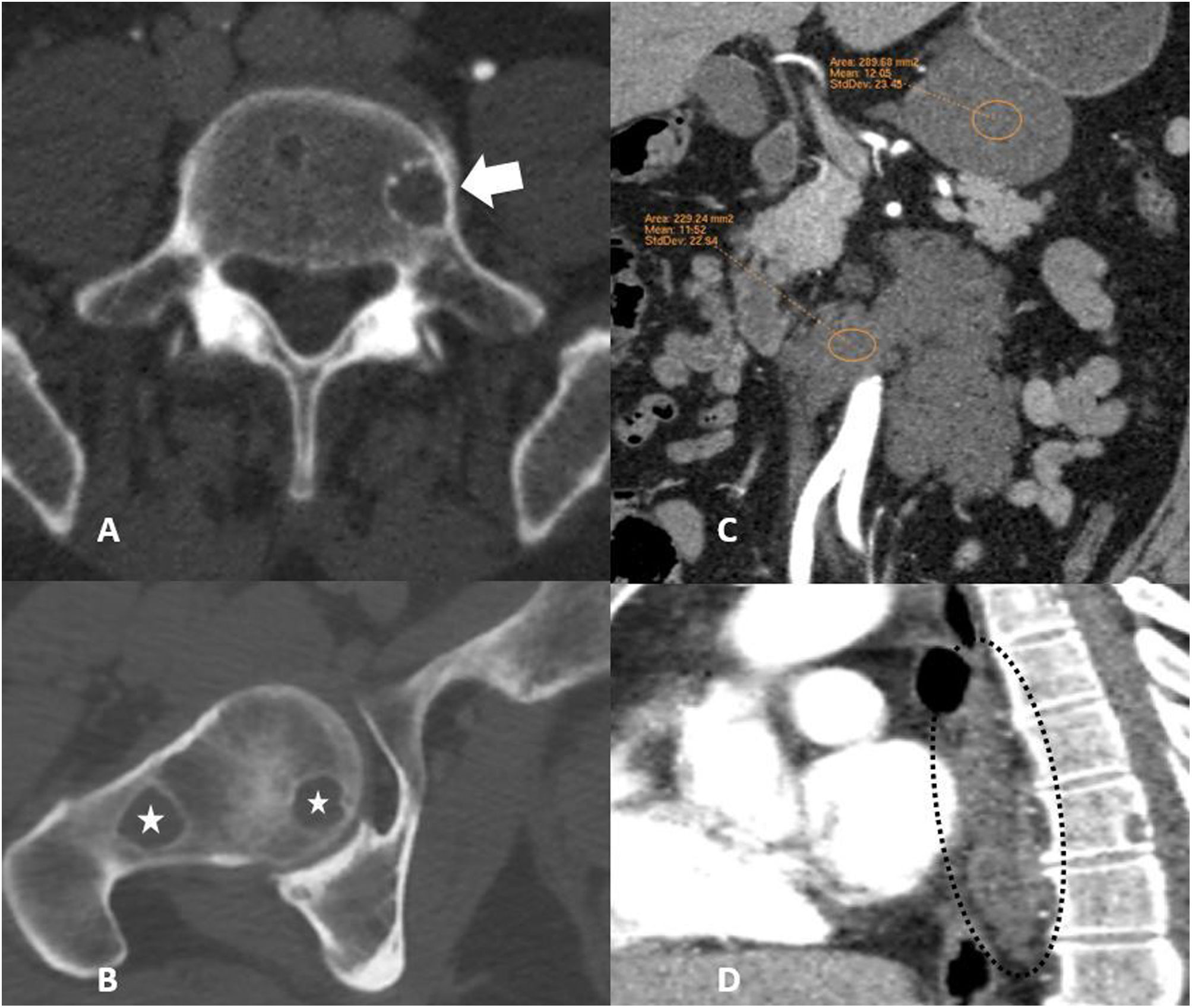

The examination ruled out acute vascular disease, but multiple lytic lesions were incidentally detected in the dorsal vertebral bodies, lumbar vertebral bodies, right iliac bone and right femoral head (Fig. 1 A and B). The lesions showed sclerotic borders, without cortical reaction or density changes in the different vascular phases. Intra-abdominally, there were two hypodense lesions with lobulated edges, one below the lower border of the gastric body and the other larger one surrounding the abdominal aorta, with no signs of vascular infiltration or contrast uptake. They had isolated punctate microcalcifications, with fluid density and no enhancement after contrast administration, compatible with lymphangiomas or lymphatic malformations (Fig. 1C). Two lesions similar to the intra-abdominal lesions were identified in the posterior mediastinum (Fig. 1D). The HU of all the osteolytic lesions were measured using a region of interest (ROI), obtaining values below 20 HU and above 10 HU in all of them (Fig. 2A). The set of findings described in the CT scan were suggestive of GLA, so the radiology department put this forward as the first possibility.

(A) Axial plane computed tomography (CT) image with bone window showing a low-density osteolytic lesion with well-defined sclerotic borders in the left half of the L5 vertebral body (arrow). (B) Axial CT image showing two osteolytic lesions with a cystic appearance and sharp margins in the right femoral head, with no accompanying cortical reaction (stars). (C) CT scan with intravenous contrast in the coronal plane showing two hypodense lesions with lobulated borders compatible with lymphangiomas or lymphatic malformations, one of them below the lower edge of the gastric body and the other larger one surrounding the abdominal aorta, with no signs of vascular infiltration or contrast uptake. (D) CT image with intravenous contrast in the sagittal plane of a mediastinal lymphangioma in contact with the posterior oesophageal wall and vertebral cystic lytic lesion (dashed circle).

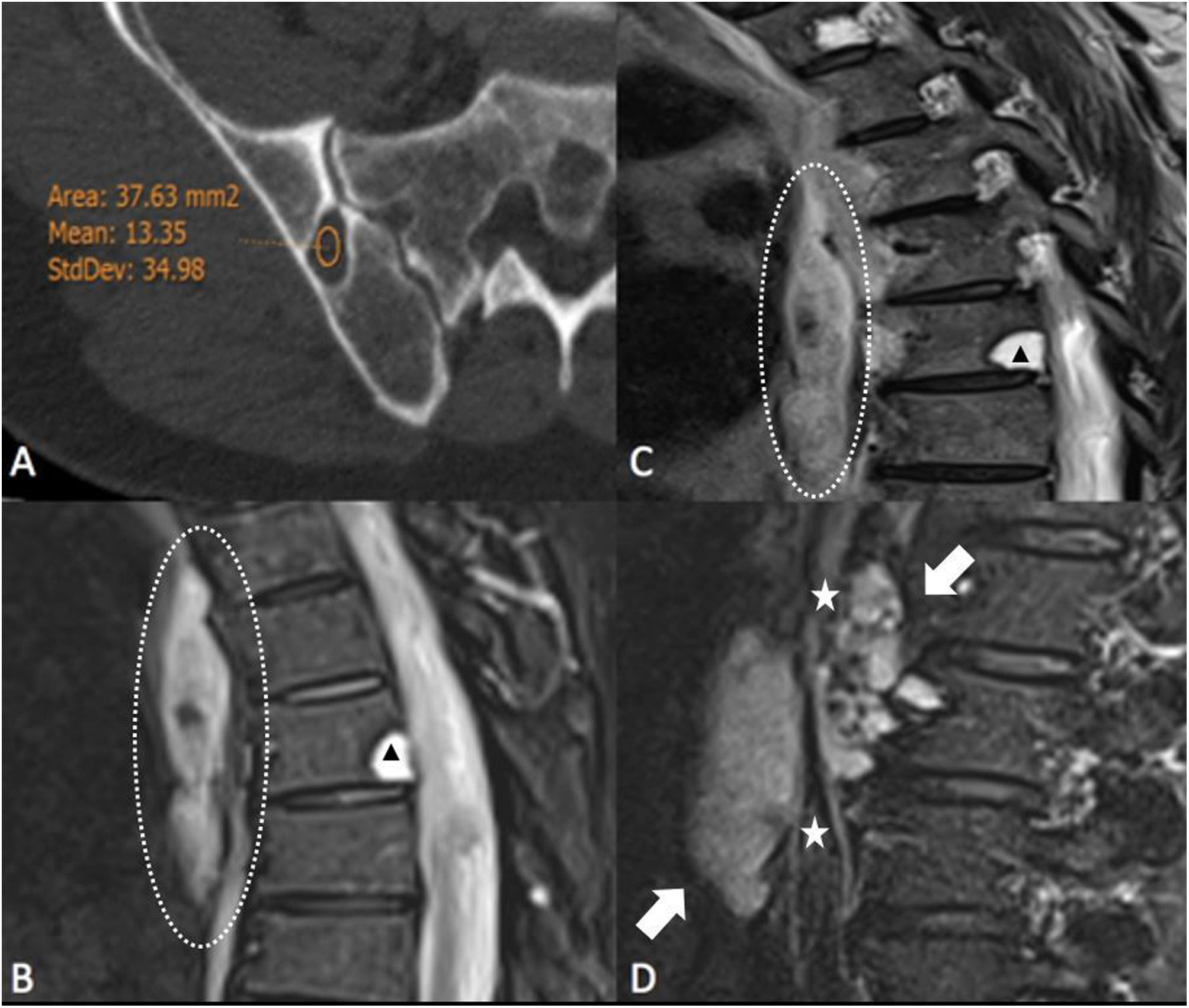

(A) Axial slice from CT scan with bone window showing Hounsfield unit (HU) measurement of one of the osteolytic lesions, in this case of the right iliac bone, showing a value of 13 HU, consistent with water-fluid density. (B and C) T2-weighted MR images and STIR sequence respectively of the dorsal spine in the sagittal plane; well-defined, markedly hyperintense vertebral bone lesions can be seen with a hypointense border (arrowheads), as well as a hyperintense lesion of fusiform morphology in the posterior mediastinum consistent with lymphangioma (dashed circles). (D) Sagittal STIR MRI of lumbar spine with retroperitoneal lymphangioma (arrows) surrounding the abdominal aorta (stars).

After the patient was admitted, a head and neck CT scan detected two osteolytic vertebral lesions similar to those described above. A positron emission tomography/CT scan was performed which showed the ametabolic nature of all the lesions. Investigations were completed with dorsolumbar MRI, where the osteolytic, mediastinal and retroperitoneal lesions were markedly hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 2B–D).

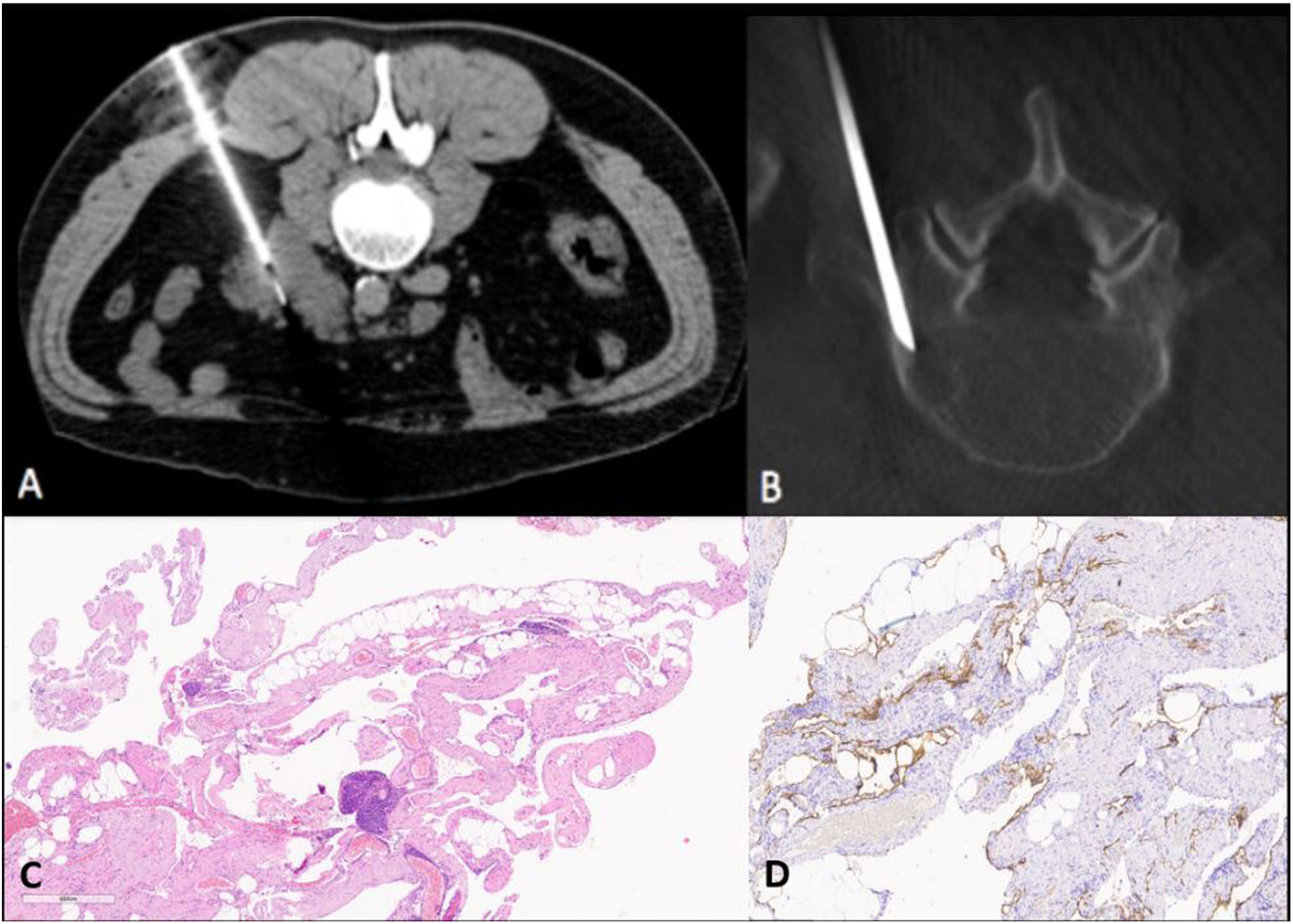

In order to confirm the diagnosis, a CT-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy was performed on one of the retroperitoneal cystic lesions (Fig. 3A), in addition to FNA and a fluoroscopy-guided core biopsy of a vertebral lesion (Fig. 3B). The pathology study ruled out the presence of malignancy in the tissue samples. Lastly, a retroperitoneal cystic lesion was surgically excised and characterised as a cystic lymphangioma (Fig. 3C and D), definitively confirming the diagnosis of GLA.

(A) CT-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) in the axial plane of one of the retroperitoneal lesions. B) Fluoroscopy-guided core needle biopsy (CNB) of an osteolytic lesion at L5. (C) Pathology. (C) Vascular lesion consisting of large-lumen structures with irregular wall thickness, focally containing smooth muscle and lymphocytic infiltrate. (D) Immunohistochemical study: D2-40 positive for lymphoid endothelial cells.

GLA is an elusive disease, with variable forms of presentation, usually diagnosed during childhood and not, as in our case, in mature adults.3 Reports in the literature of GLA in adulthood as a chance finding in asymptomatic patients,6 coupled with the absence of rib lesions in radiological tests, are therefore extremely rare.1,2,4,5,7,8

The prognosis of this condition depends on the structures affected.7 In children, the classic symptoms consist of chylous pleural effusion, dyspnoea, bone pain and pathological fractures,9 as well as protein loss, compression of internal structures, pericardial effusion and chylous ascites.8 Differential diagnosis with other CLA listed by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) should be established in this age group. Gorham-Stout disease, associated with progressive cortical destruction and kaposiform lymphangiomatosis (recently classified as a subtype of GLA) have characteristic pathology findings10 and an aggressive disease course, with coagulation abnormalities.1,4,7,10

Although unusual, it is possible to find rare cases of GLA which produce symptoms and are discovered in adulthood, as well as those in which the patient is completely asymptomatic.6 Diagnosis by imaging techniques in these cases becomes even more important,3,10 and the radiologist has to consider differential diagnoses of neoplastic aetiology, such as multiple myeloma or metastasis.1 If radiological and clinical findings are insufficient for diagnosis, histological examination is the next step, and it is preferable to avoid specimens from lytic lesions because of their lower diagnostic yield and the risk of refractory pleural effusion in the case of rib biopsies.10

Rib involvement is a consistent finding in the literature1,2,4,5,7,8,10 and according to some authors the ribs are the bones most commonly affected by osteolytic lesions.4,5 In our case, the cystic and avascular nature of the bone lesions identified by measuring their HU on CT made metastatic aetiology unlikely and suggested the diagnosis of GLA, as despite no rib involvement being found, the presence of these lesions with respect to the cortex is a finding widely described in the literature and constant in this condition.9 These findings, along with lesions compatible with cystic lymphangiomas or intra-abdominal and thoracic lymphatic malformations, made it necessary to consider a disorder within the spectrum of CLA,8 with the patient's advanced age and the absence of accompanying clinical manifestations excluding other conditions within this spectrum and GLA being the most likely diagnosis.

Finally, treatment of this disorder, like others within the spectrum of CLA, is focused on preventing progression by administering different drugs against molecular targets, such as tyrosine kinase, mTOR and vascular endothelial growth factor and, when necessary, alleviating the symptoms through surgical or interventional techniques.3,10

ConclusionsDiagnosis of GLA can be complex, as it is so rare and because of the general lack of awareness of the condition. Moreover, the clinical variability of presentation and the virtual or complete lack of symptoms in adult patients make it a challenge for both the radiologist and the clinician. Because of its rareness, we have presented a challenging case here in the hope of illustrating the diagnostic problems this disorder can pose.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for study integrity: JSS.

- 2.

Study conception: JSS.

- 3.

Study design: JSS.

- 4.

Data acquisition: JSS.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: JSS.

- 6.

Literature search: JSS.

- 7.

Drafting of the paper: JSS, EAV, JGM and AAM.

- 8.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: JSS, JGM, AAM and EAV.

- 9.

Approval of the final version: JSS, JGM, AAM and EAV.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.