Gastropericardial fistula is a rare, extremely serious and life-threatening condition. Its most common aetiology is secondary to iatrogenic injury following gastric surgery. Clinical manifestations may be non-specific with precordial pain, simulating an acute coronary syndrome, and may be accompanied by electrocardiogram abnormalities. Diagnosis is made by thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) with oral and intravenous contrast. Treatment is surgical and consists of repair of the anomalous communication. We present the case of an 81-year-old male patient with gastropericardial fistula who underwent surgery, with the aim of reviewing the diagnosis and the appropriate therapeutic strategy.

La fistula gastropericárdica es una patología infrecuente y extremadamente grave que pone en riesgo la vida del paciente. Su etiología más frecuente es la secundaria a una lesión iatrogénica tras una cirugía gástrica. La clínica puede ser inespecífica con dolor precordial, simulando un síndrome coronario agudo, y acompañarse de alteraciones en el electrocardiograma. El diagnóstico se realiza mediante tomografía computarizada (TC) toracoabdominal con contraste oral y endovenoso. El tratamiento es quirúrgico y consiste en la reparación de la comunicación anómala. Se presenta un caso de un paciente de 81 años con fístula gastropericárdica intervenido, con el objetivo de revisar el diagnóstico y la estrategia terapéutica apropiados.

Gastropericardial fistula is an abnormal communication between the stomach and the pericardium.1 It is a rare disorder which can be extremely serious due to the risk of triggering critical situations such as cardiac tamponade, sepsis and haemodynamic instability, with the consequent risk to the patient's life.2 The aetiology is multiple, the most common cause being secondary to iatrogenic injury after gastro-oesophageal surgery (anti-reflux techniques, bariatric surgery or oncological resections) or after an interventional procedure (endoscopic techniques), with open or closed trauma, infectious processes or caustic ingestion as less common causes.3,4 The signs and symptoms are non-specific, with precordial and epigastric pain, fever, dyspnoea and electrocardiogram abnormalities.3 Diagnosis is made by computed tomography (CT) of chest and abdomen with intravenous contrast (IVC). Oral contrast can also be used, although with caution due to its possible adverse effects on the pericardium.3 Treatment is surgical and consists of repairing the abnormal communication.3,4 We present here the case of an 81-year-old patient with gastropericardial fistula who successfully underwent early surgery, in order to highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to this condition and to review the diagnosis and therapeutic strategy.

Case reportThis was an 81-year-old male former smoker with obesity and dyslipidaemia. He had undergone surgery for a hydatid cyst of the left hepatic lobe in 1969 and for duodenal ulcer in 1979 via midline laparotomy, with subsequent incisional hernia repaired on several occasions with placement of supra-aponeurotic meshes (Vicryl® mesh and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene [ePTFE] mesh). He came to Accident and Emergency with a history of chest pain for several hours, radiating to the jaw. The pain worsened with inspiration and posture and improved with Cafinitrina® [caffeine and nitroglycerin] and paracetamol. Coinciding with the pain, the electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in the inferior lead. The patient was admitted to Cardiology with a diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome.

The chest X-ray showed pneumopericardium, which initially went unnoticed (Fig. 1A). The "heart code" protocol was activated, defined in our centre as chest pain of half an hour's duration refractory to medical treatment with ST elevation in more than two contiguous leads. The cardiology department performed a coronary angiogram in which no significant coronary lesions were found, but a pericardial effusion was identified, the electrocardiogram changes being attributed to pericarditis. In addition, during the procedure an artefact was detected adjacent to the right heart chambers. Once the procedure was completed, the chest X-ray was reviewed and the radiodiagnostic service was contacted to confirm that it was a pneumopericardium, and it was decided to perform a CT scan for further assessment.

A) Chest X-ray. Radiolucent line partially surrounding the left ventricle compatible with mild pneumopericardium (arrow).

B–D) Chest CT with IVC with lung window, axial (B and D) and sagittal (C) planes. B–D) Air contents with crescent morphology surrounding the anterior surface, both lateral surfaces and the inferior surface of the heart with a maximum thickness of approximately 35 mm in relation to the pneumopericardium (yellow asterisk). C and D) In the outer layers of the stomach wall, in the region of the body at the greater curvature, there is an air bubble image that could be a diverticulum, in intimate contact with the anterior and medial wall of the diaphragm. Although there is no clear loss of continuity, it is the area of closest proximity to the pneumopericardium (arrows).

The CT chest and abdomen with IVC showed air contents with a crescent morphology extending over the anterior aspect, both lateral aspects and the inferior aspect of the heart with a maximum thickness of approximately 35 mm, in relation to pneumopericardium (Fig. 1B–D). Small air bubbles were also seen in the right pericardial recesses, predominantly in the aortic recess, which also showed a small amount of fluid. In the outer layers of the stomach wall, in the region of the body at the greater curvature, there was an air bubble image, which might have been a diverticulum, in close contact with the anterior and medial wall of the diaphragm, which, although there was no clear loss of continuity, was the area of closest proximity to the pneumopericardium (Fig. 1C, D). There was no evidence of clear tracheal or bronchial fistulae. Oral contrast (diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium, Gastrografin®) was administered without contrast extravasation in the oesophagus (Fig. 2A) or in the stomach, although the stomach did not show complete filling with contrast. Fat striation was identified adjacent to the oesophagogastric junction (Fig. 2B).

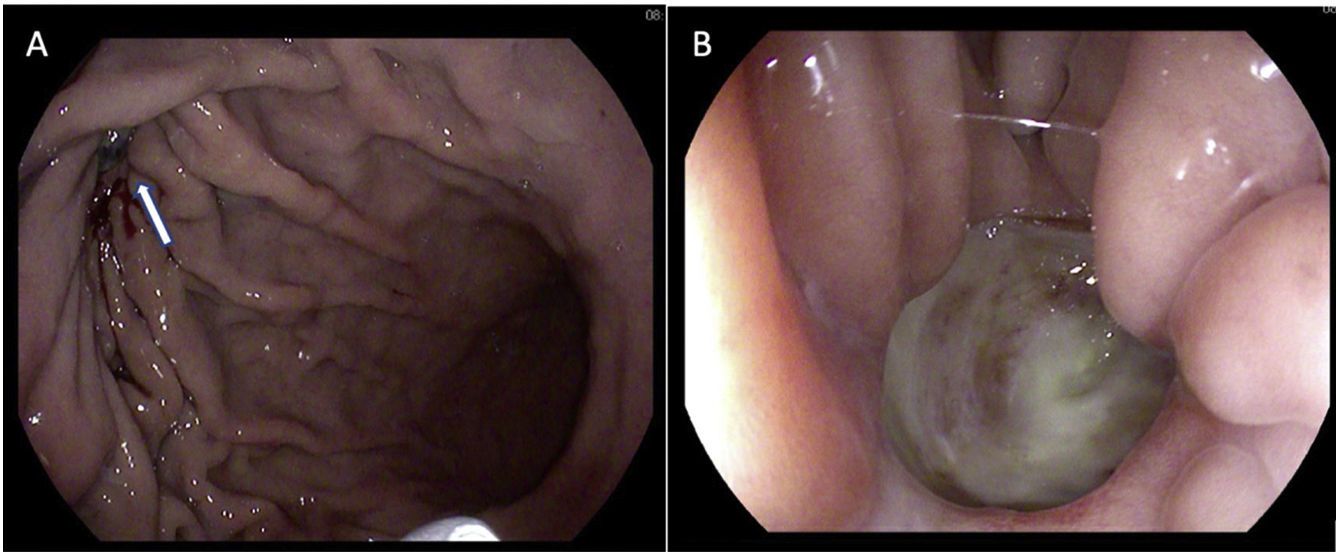

Given the findings, a gastroscopy was performed, which showed a probable 8 mm diverticulum in the greater curvature of the gastric body, towards the anterior surface, without surrounding erythema, with a fibrin background simulating an ulcer (Fig. 3A). In the central area there was a punctate pore, suggestive of a fistula (Fig. 3B). With the diagnosis of gastropericardial fistula, open surgery was decided on due to the patient's previous operations. During surgery, a fistulous orifice of 1 cm in diameter was identified in the greater curvature of the stomach. The pericardial orifice was only millimetres in size and was enlarged by scissors, creating a pericardial window, to empty the serous pericardial effusion (<50 cc). Segmental resection of the gastric greater curvature, including the fistulous orifice, was performed with an endograft and the staple line was reinforced with absorbable monofilament suture. The diaphragmatic orifice was repaired with a non-absorbable suture. The patient progressed favourably and was discharged on day 5 postoperatively. At the 3-month outpatient check-up he was asymptomatic in both gastric and cardiac terms. Pathology showed only inflammatory changes in the gastric wall.

Gastroscopy images. A) In the greater curvature of the gastric body there is a rounded image of about 8 mm with well-defined borders (arrow) that seems to correspond to a diverticulum with a fibrin background. B) In the central area a punctate pore/bubble image is visualised which could be suggestive of a diverticulum complicated by fistulisation. Oozing from the fistula would cover the walls of the diverticulum, simulating the appearance of an ulcer.

Gastropericardial fistula is a potentially fatal disorder as it can cause cardiac tamponade. The most common cause is iatrogenic after gastro-oesophageal surgery (Nissen fundoplication, tumour resections, peptic ulcer surgery), and usually occurs years after surgery, or after interventional procedures (bronchoscopy, endoscopy, thoracentesis).4,5 Other less common causes are open or closed trauma, refractory gastric ulcers, ingestion of foreign bodies or caustic agents, neoplasms or infections by gas-producing germs.3,6,7

These patients usually present with stabbing chest pain and dyspnoea, with characteristic irradiation of pain to the left shoulder due to pericardial irritation at the time of diagnosis. However, some patients report other symptoms, such as abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding or swallowing disturbances, such as dysphagia or vomiting, for years before definitive diagnosis.3,6

Diagnosis is primarily radiological. Chest X-ray may show a radiolucent band partially or completely surrounding the cardiac silhouette corresponding to gas in the pericardium, which may also be accompanied by fluid (hydropneumopericardium), raising the suspicion of gastropericardial fistula.4 CT of chest/abdomen with IVC is the most sensitive test for the diagnosis of this condition. Hydropneumopericardium, pericardial thickening and increased pericardial uptake can be identified. Rarely will we be able to clearly visualise the fistulous tract. Oral contrast tends to be used with caution, as its potential adverse effects on the pericardium are unknown. Image reconstruction in the three spatial planes allows the fistula to be properly visualised and surgery to be planned.4–6 However, if radiological studies are inconclusive, gastroscopy to clarify the diagnosis has been shown to be useful without increasing the risk of cardiac tamponade.8

Treatment of pericardial fistula is surgical and should be performed early, with antibiotic and antifungal coverage.3,8 The approach can be laparoscopic or by laparotomy, depending on the patient's characteristics and the surgeon's experience.9 In the case presented, midline laparotomy was decided on due to the history of multiple abdominal surgical interventions and the existence of a chronic infection of the parietal prosthesis, placed in the past during incisional hernia repair surgery in supra-aponeurotic position, which was removed during the intervention. Regardless of the approach, all strategies should include drainage of the pericardium, resection of the fistulous tract, repair of the diaphragm, gastric repair and additional treatment of underlying pathology based on intraoperative findings.10 In this case, the aetiology of the fistula was probably associated with a history of previous surgical interventions, which is why the gastric body had remained adhered to the diaphragm, eroding it and finally generating the fistula towards the underlying pericardium.

ConclusionsGastropericardial fistula is a rare but life-threatening condition. It is difficult to diagnose, as it is very unlikely to be suspected clinically, given that the symptoms are typical of an acute coronary syndrome. A history of oesophageal or gastric surgery, as well as a history of peptic ulcer, are the most common causes without a specific temporal relationship. The multidisciplinary approach to these patients is essential for correct diagnosis and early surgery to ensure successful treatment.

Authors' contributionsResponsible for the integrity of the study: B. Carrasco Aguilera.

Study design: B. Carrasco Aguilera, M. Martínez-Cachero García and L. Sanz Álvarez.

Study design: B. Carrasco Aguilera and M. Martínez-Cachero García.

Data collection: B. Carrasco Aguilera, M. Martínez-Cachero García and F. Cadenas Fernández.

Literature search: B. Carrasco Aguilera, P del Val Ruiz and L. Sanz Álvarez.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: B. Carrasco Aguilera, M. Martínez-Cachero García and L. Sanz Álvarez.

Approval of the final version: all the authors.

FundingThe study did not require external funding.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have any conflict of interest either with the material and methods used in the study or with the findings described in the study.