Traumatic injuries of the limbs are very common and account for a large number of imaging examinations, especially in emergency departments. These injuries can often be resolved if they are recognized and treated appropriately. Their diagnosis requires a complete clinical assessment and the correct interpretation of the appropriate imaging tests. Radiologists play an important role, especially in diagnosing lesions that can go undetected. To this end, radiologists need to know the normal anatomy and its variants, the mechanisms of injury, and the indications for different imaging tests, among which plain-film X-rays are the main technique for the initial evaluation. This article aims to review the relevant characteristics of limb fractures in adults and of lesions that can be associated with these fractures, as well as how to describe them to ensure appropriate clinical management.

Las lesiones traumáticas de las extremidades son muy frecuentes y suponen un volumen importante de las exploraciones que se realizan diariamente en los servicios de Radiología, sobre todo en urgencias. A menudo se pueden resolver si se reconocen y tratan adecuadamente, lo que implica la necesidad de una evaluación clínica completa y un estudio radiológico adecuado y correctamente interpretado. Aquí los radiólogos tenemos un papel importante sobre todo en el diagnóstico de aquellas lesiones que pueden pasar desapercibidas; para ello necesitamos conocer la anatomía normal y sus variantes, los mecanismos de lesión y las indicaciones de las distintas pruebas de imagen, siendo la radiología simple la principal técnica en la valoración inicial. El objetivo de este artículo es revisar las características relevantes de las fracturas de las extremidades en adultos, las posibles lesiones asociadas y cómo describirlas para un manejo clínico adecuado.

The diagnosis of a fracture is based on imaging tests, and plain X-ray continues to be the first and often only technique necessary if we know how to interpret it. Our experience is particularly valuable in the diagnosis of the most subtle injuries, as large fractures and dislocations cause no hesitation even for the less experienced observer.1 Having adequate clinical data and knowing the injury mechanism helps us find the main injury and possible associated local or distant injuries. We need to be familiar with the most common classifications, although what is important in the radiological report is to adequately describe the characteristics that may modify clinical management. Limb trauma is a very broad topic, so our aim was to review the basic concepts to adequately describe the injuries and detail the key aspects of some of them, which we selected either for their frequency or their complexity.

Basic concepts of skeletal trauma and radiological diagnosisA fracture is a break in the continuity of the bone, cartilage or both. A dislocation consists of the complete loss of congruence between the bony surfaces of a joint; if the loss of contact is incomplete, we call it subluxation. Abnormal separation between the bony ends of a syndesmosis or a symphysis is called a diastasis.

Diagnosis starts with the X-ray. At least two views are necessary, perpendicular as far as possible, and they need to be of adequate quality. We go on to take additional views when we strongly suspect a fracture but it is not confirmed by the basic perpendicular views,2 bearing in mind that the fracture may only be visible in one of the available views. The joint adjacent to the fracture should be included and, in shaft fractures, the proximal and distal joints. Comparative X-rays are useful in some cases that we will discuss, as well as in selected cases of trauma in children, but only when there is uncertainty.

In subtle fractures in particular, assessment of the soft tissues is essential; we look for thickening and increased density of the soft tissues, displacement of the fatty planes, joint effusion or lipohaemarthrosis.3

It will sometimes be necessary to use other diagnostic techniques. Computed tomography (CT) makes it possible to identify subtle fractures, assess the extension of a fracture into a joint, detect possible intra-articular free bodies and characterise fractures in complex anatomical regions4 (for example, shoulder, elbow, sternoclavicular joint, ankle, foot). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the method of choice for assessing joint injuries and diagnosing occult fractures for its sensitivity in detecting bone oedema.3,5–7 However, with its ability to differentiate materials, dual-energy CT is now increasingly being described as a suitable technique for assessing bone oedema.8,9 Digital tomosynthesis has a lower sensitivity than CT but higher than X-ray for detecting fractures.10,11

Description of fractures and joint injuries. TerminologyWhen describing a fracture, we should always include its location (fractured bone and which part of it), direction of the fracture line, degree of comminution, position of the fragments, extension into a joint, presence of effusion (for example, fat pad sign in elbow), lipohaemarthrosis or gas or foreign bodies, indicating an open wound.3,5,6

A precise description is usually enough to guide clinical management (Figs. 1 and 2). There are specific grading systems for many fractures and it is best to familiarise ourselves with the one used by our orthopaedic surgeons.5 One of the most widely used is that of the Association for Osteosynthesis/Orthopaedic Trauma Association (AO/OTA), as it is detailed and applicable to most fracture sites.12 The use of eponyms is not recommended.13

Fractures and dislocations of the upper limbsShoulder girdle and humerus- •

Acromioclavicular dislocation

The severity of this injury depends on the degree of rupture of the acromioclavicular (AC) and coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments. The Rockwood classification, which categorises dislocations into six types, is used to describe them14:

- –

Type I: ligaments intact; normal X-ray.

- –

Type II: complete rupture of AC and incomplete rupture of CC; AC separation >7 mm.

- –

Type III: complete rupture of AC and CC; increase in CC distance (25–100% compared to contralateral CC distance).

- –

Types IV, V and VI: complete rupture of AC and CC with, respectively, posterior, superior (100–300%) and anterior-inferior displacement of the clavicle. These are uncommon injuries, especially type VI, which is associated with a risk of injury to the neurovascular bundle. Treatment is always surgical.

Comparative X-rays are useful in assessing the actual degree of displacement. Stress X-rays are no longer recommended.15,16

- •

Clavicle fractures

Clavicle fractures are classified according to the location into fractures of the middle (the most common), distal and proximal thirds. Fractures of the middle third can be segmental; overriding of fragments is common and shortening may occur. Those of the distal third may be associated with injury to the CC ligaments and are considered unstable. Comparative X-rays are useful in both types. In proximal fractures, CT is recommended to assess the sternoclavicular joint.3,17

- •

Sternoclavicular dislocation

This can be anterior (far more common) or posterior. This is difficult to diagnose by X-ray; intravenous contrast-enhanced CT is indicated, as posterior dislocation can be associated with vascular injury, tracheal laceration and pneumothorax.1,3

- •

Scapula fractures

Scapula fractures are described according to their location as fractures of the body (the most common), the neck (the glenoid separates from the rest of the scapula), the glenoid (joints), the spine and the acromion and coracoid processes. Combined fracture of the clavicle and the neck of the ipsilateral scapula is known as "floating shoulder".18

- •

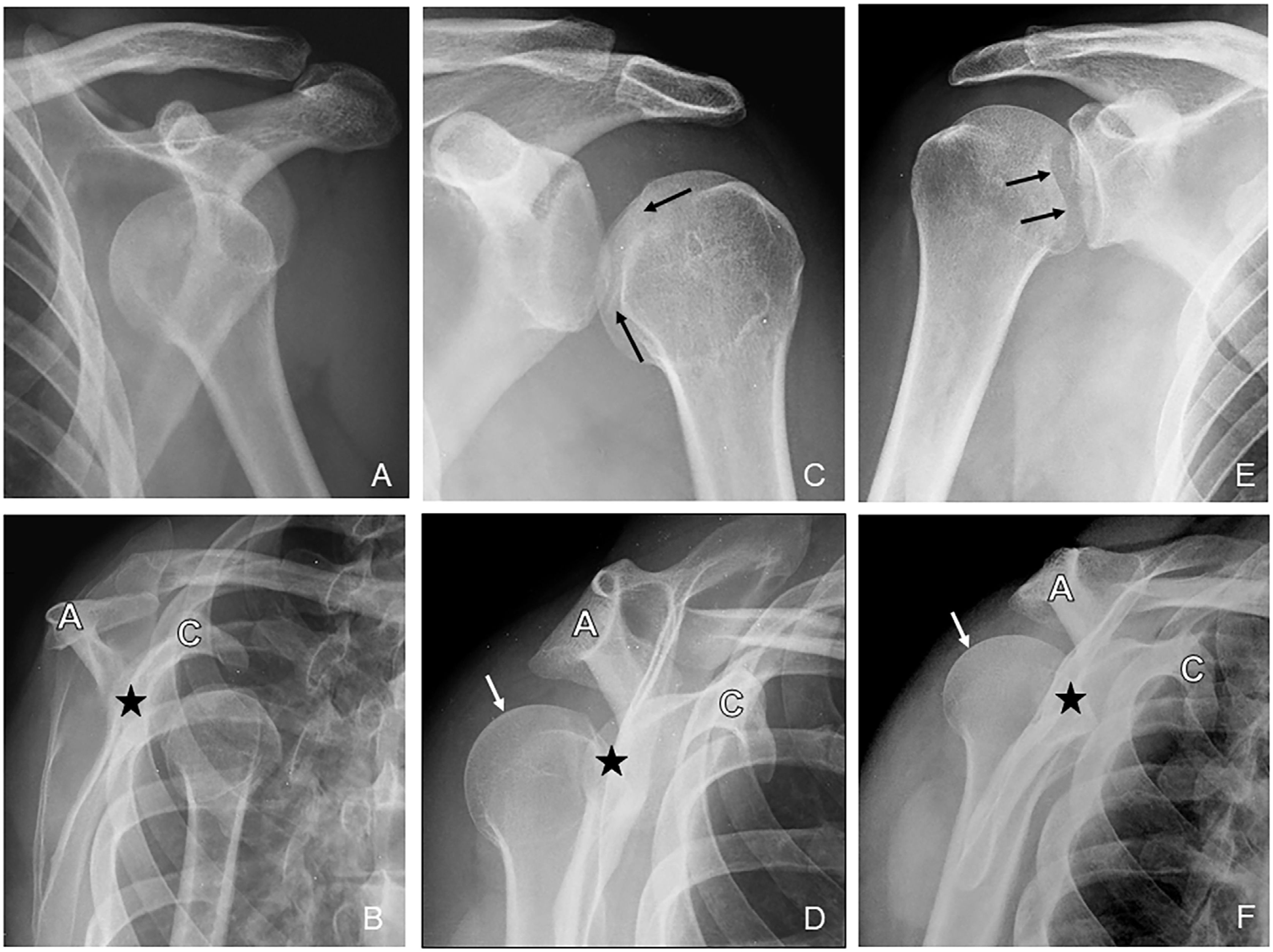

Glenohumeral dislocation (Fig. 3)

- –

Anterior dislocation (95%): the humerus is usually displaced inferiorly and medially, below the coracoid process, with anterior-posterior (AP) X-ray being sufficient for diagnosis. Intrathoracic displacement or displacement below the glenoid or clavicle are less common. In becoming displaced, the superior-lateral portion of the humeral head collides with the anterior-inferior rim of the glenoid, and this can cause an impacted fracture (Hill-Sachs lesion). Less frequently, the bony rim of the glenoid can be fractured (bony Bankart lesion). Both fractures are associated with instability and recurrent dislocation.18 In patients aged under 50, this type of dislocation can be associated with a fracture of the greater tubercle.1,3,19

- –

Posterior dislocation (2–4%): associated with mechanisms of intense muscle contraction (seizures, electrocution), and can be bilateral. It can be associated with fracture of the medial edge of the humeral head (reverse Hill-Sachs fracture), the posterior glenoid rim (reverse Bankart fracture) and the greater tubercle. It frequently goes unnoticed on AP X-ray, requiring complementary views (trans-scapular, axillary).1,7,18 If in doubt, a CT should be performed.

- –

Pure inferior dislocation (erect dislocation) and superior dislocation (through the rotator cuff), both very rare.

Figure 3.Glenohumeral dislocation. Anterior dislocation: on AP X-rays of the shoulder (A) and lateral of the scapula (B), the humeral head is displaced anterior and inferior to the glenoid (star), below the coracoid process. Posterior dislocation: 2 different cases showing the variability in radiological findings. The AP X-ray in the first case (C) shows an enlarged glenohumeral space and internal rotation of the humerus ("light bulb sign"), whereas in the second case (E), the glenohumeral space is clamped, asymmetrical, and there is no rotation of the head. The sclerotic line (black arrows) indicates the impact fracture of the head at the posterior margin of the glenoid (reverse Hill-Sachs lesion); this is the “double cortical line” sign. The lateral scapula X-ray in both cases (D, F) shows the posterior displacement of the humeral head (white arrow) with respect to the glenoid (star). A: acromion; C: coracoid process.

- –

- •

Fracture of the proximal humerus

Anatomically, the proximal humerus consists of four parts: head, diaphysis or shaft, greater tubercle and lesser tubercle. The anatomical neck separates the head from the tubercle segment; the joint capsule is inserted into it. The surgical neck (metaphysis) separates the tubercle segment from the diaphysis and its cortex is called the calcar.18

The most widely used classification is the Neer classification,18,20 based on the degree of displacement and angulation of the four parts described above, regardless of the number of bone fragments. A fracture is considered displaced if the fragments show displacement >1 cm or angulation >45°.

- •

Fracture of the distal humerus

The most widely-used classification system is the AO/OTA; it divides them into type A or extra-articular (avulsion fractures of the epicondyle and epitrochlea; metaphyseal fracture); type B or partial articular (condyle or trochlea); type C or complete articular (intercondylar and metaphyseal fracture, which may have a T or Y configuration).12

Elbow and forearm- •

Dislocated elbow

Most are posterior or posterior-lateral and are usually associated with a fracture of the radial head and coronoid process (terrible triad).21 Isolated dislocation of the radial head is rare in adults; we need to look for an associated fracture of the ulna (Monteggia fracture-dislocation).

- •

Proximal radius fractures

These are the most common elbow fractures in adults. There are almost always associated signs of joint effusion on the lateral X-ray and displacement of the supinator fat line is common. The modified Mason classification22 is used to describe these fractures, based on the degree of displacement, depression and comminution of the head. Most nondisplaced fractures are isolated injuries. Displaced fractures are usually associated with other injuries, such as elbow dislocation, forming part of the “terrible triad”, or the Essex-Lopresti injury in the forearm.23

- •

Forearm fractures

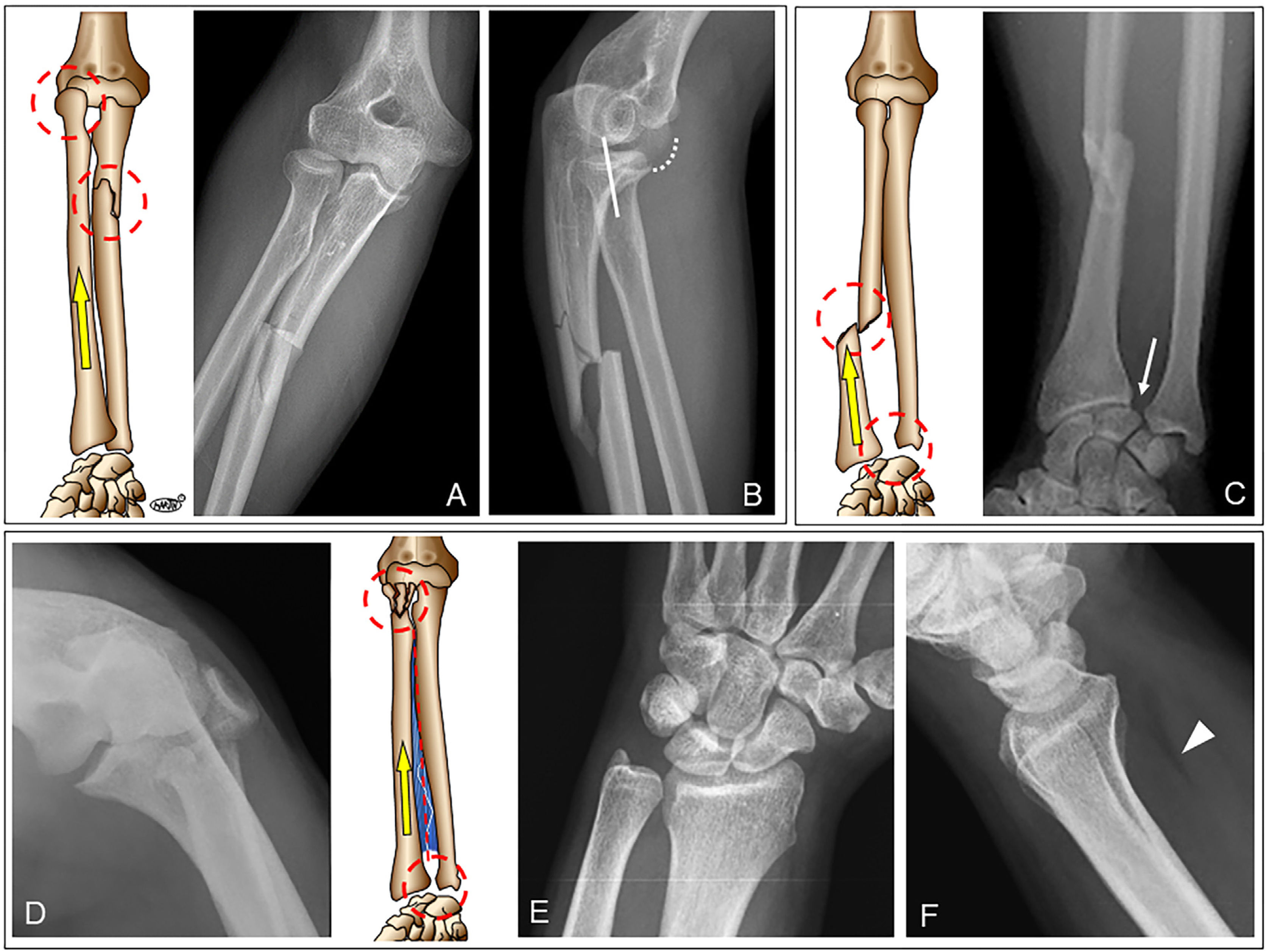

The forearm is a ring made up of two long bones (ulna and radius), two joints (proximal and distal radioulnar) and the interosseous membrane. Fracture of one of the bones is almost invariably accompanied by fracture in the other bone or by a dislocation; in addition, there may be rupture of the interosseous membrane. The only exception is an isolated fracture of the ulna ("nightstick" fracture), caused by a direct blow. Isolated fracture of the radial shaft is very rare. Other injuries are caused by torsion or bending forces, which break the ring at two points1,23 (Fig. 4):

- –

Diaphyseal fracture of both bones.

- –

Monteggia fracture-dislocation: fracture of the ulna, usually the proximal shaft, and dislocation of the radial head (anterior or posterior).

- –

Galeazzi fracture-dislocation: fracture of the radial shaft in its middle or distal third and dislocation or instability of the distal radioulnar joint.

- –

Essex-Lopresti injury: rare and serious injury that causes longitudinal instability of the forearm. Characterised by fracture of the radial head, frequently comminuted, rupture of the interosseous membrane and dislocation/instability of the distal radioulnar joint. Injury to this joint may go unnoticed on initial X-rays and should be suspected in a radial head fracture, especially a comminuted one, associated with wrist pain. Comparative X-rays can help.19

(A and B) Monteggia fracture-dislocation. Comminuted fracture of the proximal segment of the shaft of the ulna and posterior-lateral dislocation of the radial head. The dislocation findings are subtle: the dotted line indicates the articular surface of the condyle; the radiocondylar line (solid white line) is the line through the centre of the neck of the radius and should intersect the centre of the condyle in any view. In both views, anterior-posterior (A) and lateral (B), the radiocondylar line does not intersect the centre of the condyle, being more evident in the lateral projection. (C) Galeazzi fracture-dislocation. Fracture of the distal segment of the radial shaft and dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint (white arrow). (D–F) Essex-Lopresti injury. Displaced fracture of the radial head. There are no apparent abnormalities at the distal radioulnar joint (E), but the lateral X-ray (F) shows a shift in the pronator fat line (arrowhead) as a sign of soft tissue injury. The joint was painful and, despite being surgically fixed, the patient developed vertical instability of the forearm.

- •

Fractures of the distal radius and ulna

They may be extra- or intra-articular (more common). We need to assess:

- –

The shortening of the radius with respect to the ulna, the inclination of the distal fragment (dorsal/volar) and if there is loss of the normal radial inclination.3,5

- –

Whether there is a fracture of the ulnar styloid and if so, location: tip, middle third, base. Fractures of the base cause instability of the distal radioulnar joint by avulsion of the triangular fibrocartilage complex.

- –

Rupture of the interosseous ligaments (most often the scapholunate, increase in distance >3 mm24,25) or other carpal bones, especially the scaphoid.

- –

Whether there is joint involvement: degree of depression or separation of the fragments (study with CT, >2 mm).19

- •

Scaphoid fracture

Scaphoid fractures are classified according to their location: proximal pole (20%), mid-portion or "waist" (70%) and distal pole (10%). Avascular necrosis (AVN) and pseudarthrosis are common complications. AVN occurs above all in fractures of the proximal pole, especially those affecting the most cranial end, if they are not detected and fixed in time.19

Up to 20% of them may initially go unnoticed; if clinical suspicion is high, it can be immobilised and the X-rays repeated in 10–14 days or, alternatively, confirmed early by tomosynthesis, CT or MRI, avoiding unnecessary immobilisation in the absence of a fracture.1,10,19

Fractures and dislocations of the lower limbsHip and femur- •

Proximal femur fractures

According to their location they are categorised as:

- –

Extracapsular fractures: avulsions of the trochanters, pertrochanteric and subtrochanteric.3,5

- –

Intracapsular fractures: of the head; of the neck (subcapital, transcervical and basicervical). The Garden classification is used to describe the degree of displacement; those with subcapital location and displaced fractures have a higher risk of AVN.26

- •

Femoral shaft fractures

These fractures tend to be associated with very significant bleeding, estimated at 1,000–1,500 ml, and this can double in open fractures.27 In patients with multiple trauma, in the absence of other bleeding injuries, femoral shaft fractures can explain the signs of haemodynamic compromise; early immobilisation of the fracture is therefore important, and to avoid possible pulmonary complications (fat embolism).5,28

KneeThe presence of joint effusion is highly indicative of injury in the context of trauma. The lateral X-ray will show occupation of the suprapatellar recess (>10 mm); if the X-ray is performed with a horizontal beam, the presence of a fat-liquid level (lipohaemarthrosis) is specific to the existence of a fracture.29,30

- •

Distal femur fractures

They are generally classified as supracondylar or extra-articular, intercondylar and isolated from the condyles.12

- •

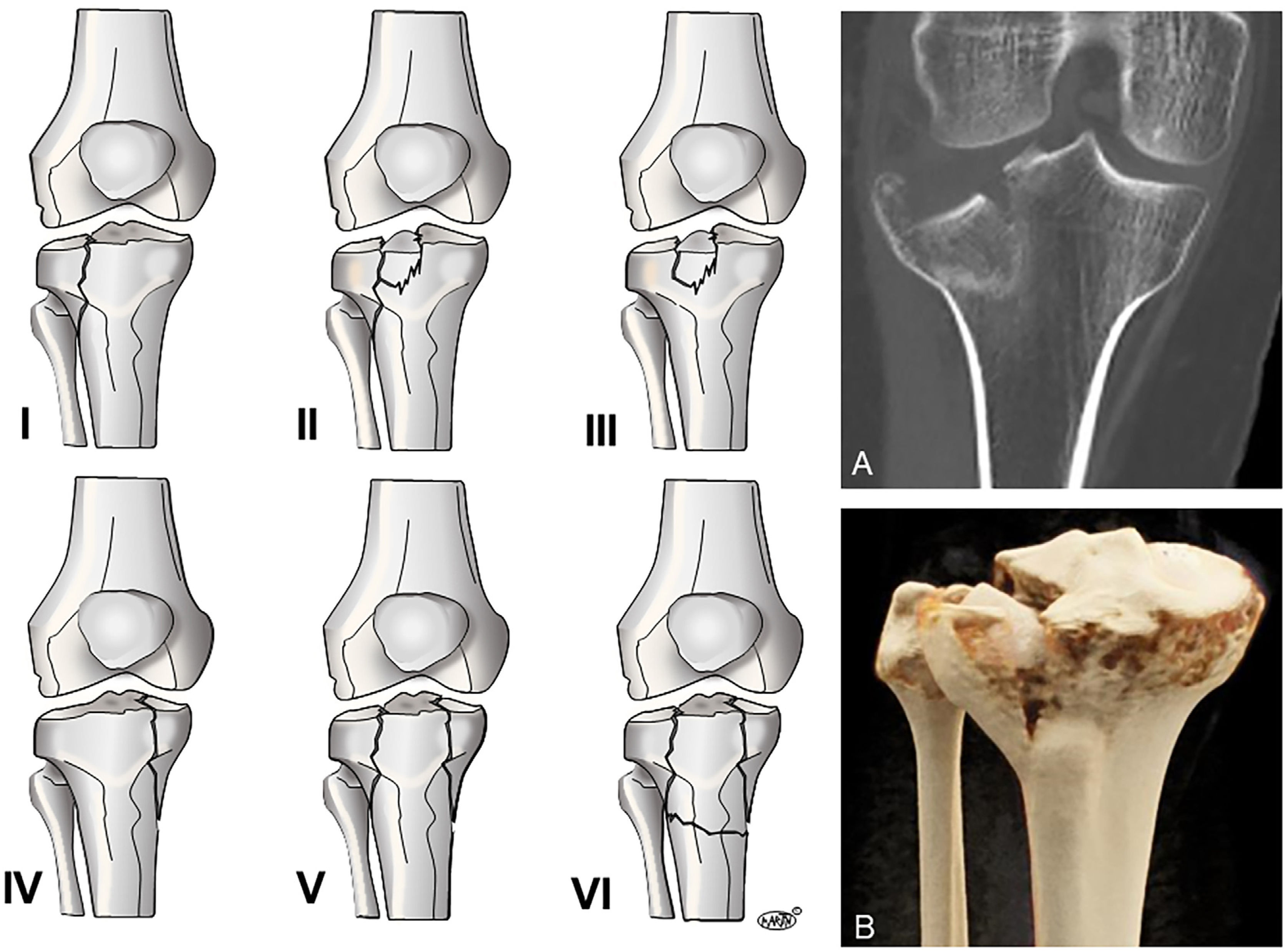

Tibial plateau fractures

These fractures can affect the lateral tibial plateau (60%), the medial tibial plateau (20%) or both (20%) and are frequently associated with injuries to the menisci or knee ligaments. For treatment, it is essential to know the degree of displacement and subsidence of the fragments, and CT is indicated. The most widely used classification is the Schatzker classification,31 (Fig. 5) although other three-dimensional classifications based on CT images have now been proposed, such as the three-column classification system.32

- •

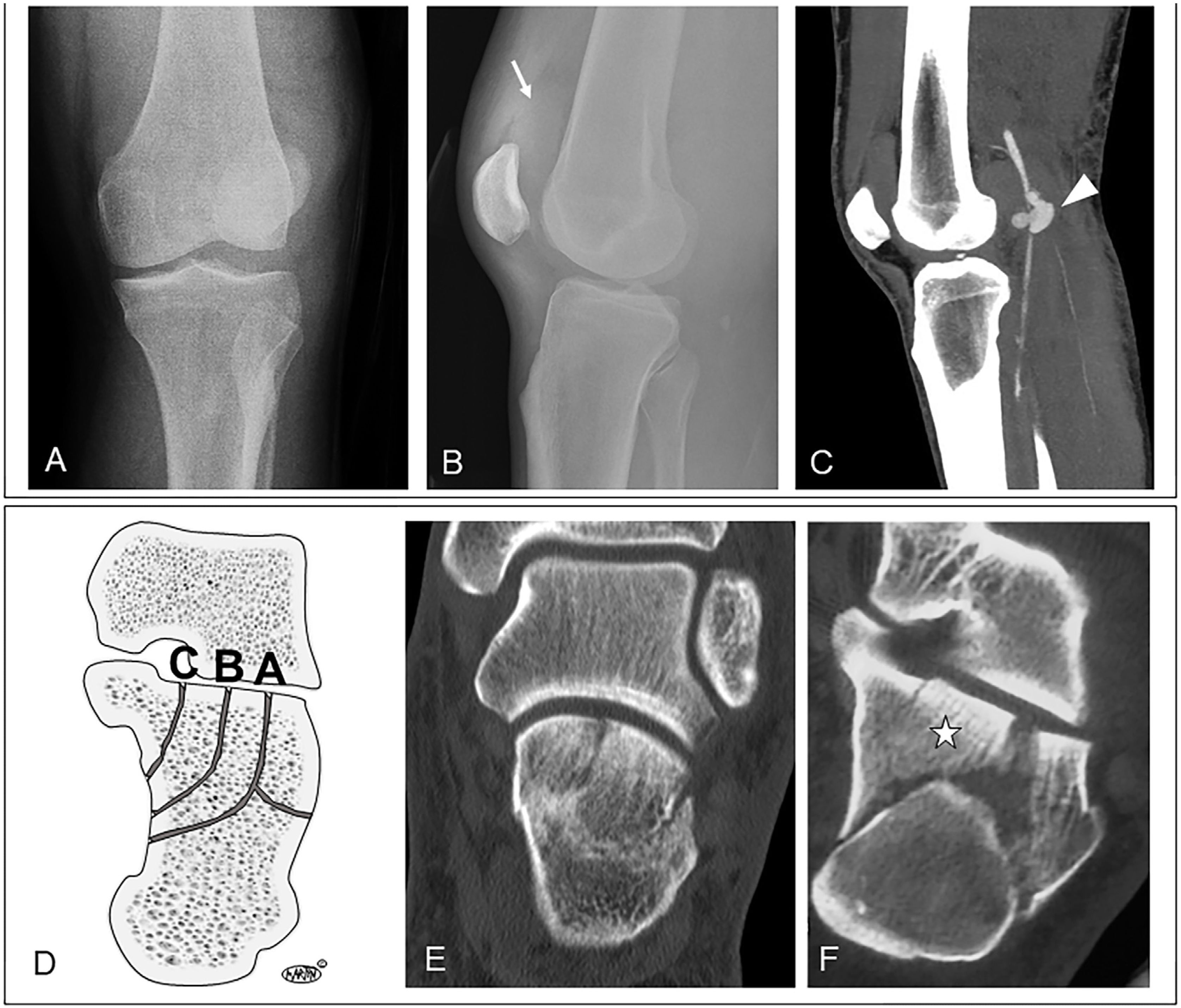

Knee dislocation

This is an orthopaedic emergency due to the risk of associated vascular injury. The incidence of knee dislocation is probably underestimated, as up to 50% reduce spontaneously, and a high degree of suspicion is therefore necessary with a thorough clinical and radiological assessment. We need to look for signs of haemarthrosis/lipohaemarthrosis, abnormal congruence and possible associated fractures, including subtle avulsion fractures (for example, Segond fracture). The most common complications are injury to the popliteal artery (20–60%) and the peroneal nerve (10–35%). Therefore, if abnormalities are detected in the pulses, either immediate or delayed, an urgent CT angiogram is indicated3,33 (Fig. 6).

(A–C) Dislocated knee with contained rupture of the popliteal artery in a young patient after a motorcycle accident. Anterior-posterior X-ray (A) shows increased medial tibiofemoral joint space and adjacent soft tissue; in the lateral X-ray (B), joint effusion can be seen (arrow). There is no visible dislocation, as they are usually reduced with immobilisation in immediate trauma care, so we have to be alert to subtle abnormalities. Sagittal CT-angiography MIP (maximum intensity projection) reconstruction (C): shows a contained rupture of the popliteal artery (arrowhead) with threadlike distal vessels. (D–F) Sanders classification of intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus (D). It is based on CT assessment of the posterior articular facet (thalamus) in a plane coronal to the posterior subtalar joint. (E) Sanders type I fracture. Although there are two joint fragments separated by a type B fracture line, there is no displacement or depression >2 mm. (E) Sanders type III AC fracture. Three joint fragments can be seen; the middle fragment (star) was depressed in a plane posterior to that shown.

Tibial shaft fractures are invariably associated with fibular shaft fracture. Fractures of the tibial and fibular shafts are frequently open fractures, they are often associated with complications such as infection, pseudarthrosis and compartment syndrome, and blood loss can be significant (500−1,000 ml).27

AnkleThe ankle joint is a ring made up of bones (tibia, fibula, talus) and their supporting ligaments (medial or deltoid, and lateral). If the ring is interrupted at a single point, either by bone or ligament injury, the injury is considered stable; if at two points, the lesion is unstable and may be associated with dislocation of the talus.

The simplest description system is that of Danis–Weber, which classifies ankle fractures into three types according to the location of the distal fibula fracture with respect to the tibiofibular syndesmosis.34

Type A or infrasyndesmotic: the fibula fracture is distal to the syndesmosis. It is usually stable and treated conservatively.

Type B or trans-syndesmotic: the fibula fracture is located at the level of the syndesmosis. It can be treated conservatively if the injury is stable (no deltoid ligament injury or syndesmosis damage).

Type C or suprasyndesmotic: the fibula fracture is proximal to the syndesmosis. It is usually unstable and requires surgical fixation.

The Maisonneuve fracture is a particular type C fracture that combines fracture of the proximal fibula, injury to the tibiofibular syndesmosis and injury to the deltoid ligament (increased tibiotalar distance), with or without fracture of the tibial malleolus. It is unstable and requires surgical treatment.

Foot- •

Calcaneus fractures

The most common mechanism is an axial load due to a fall from a height, so 10% of cases also have vertebral compression fractures in the thoracic or lumbar spine, more than 20% have injuries to the lower extremities and in 10% they are bilateral. They are classified as intra-articular if they affect the posterior superior articular facet (or thalamus), or extra-articular when they do not (posterior tuberosity, anterior process, medial process, sustentaculum tali). Intra-articular fractures are much more common, have a worse prognosis and usually require surgical reduction. They require a CT study and the most widely used classification is the Sanders system, based on the number of fragments that affect the posterior articular facet displaced by more than 2 mm35,36 (Figure 6):

- –

Type I: not displaced (<2 mm), regardless of the number of fracture lines. May benefit from orthopaedic treatment.

- –

Type II: two joint fragments with displacement. Subdivided into A, B or C, depending on whether the fracture sits laterally, centrally or medially in the posterior articular facet.

- –

Type III: three joint fragments, with a depressed middle fragment. Subdivided into AB, AC and BC, depending on the location of the fracture lines.

- –

Type IV: four or more fragments.

The prognosis is worse in fractures with a higher degree of comminution (III and IV).

- •

Tarsometatarsal fracture-dislocation (Lisfranc's)

This can affect the Lisfranc ligament in isolation (it joins the first cuneiform to the base of the second metatarsal), giving rise, as the only finding, to a widening of the space between the bases of the first and second metatarsals, with loss of the alignment between the second metatarsal and the second cuneiform. More often there is a more extensive, complete or partial injury of the tarsometatarsal joint, with fracture of the metatarsal bases, cuneiforms and cuboids, with or without frank dislocation. Complete fracture-dislocation can be of two types: homolateral, in which all the metatarsals are displaced laterally, or divergent, in which the first metatarsal is displaced medially and the rest are displaced laterally.37

It often requires CT assessment.

- •

Fracture of the metatarsals and phalanges

These fractures are described by location as of the base, the shaft or the distal end. In the metatarsals, the distal end includes the neck and the head.

Fractures of the proximal end of the fifth metatarsal are the most common. There are three types38:

- –

Tuberosity avulsion fracture: conservative treatment.

- –

Jones fracture: transverse fracture at 1.5−3 cm from the tuberosity, at the level of the joint with the base of the fourth metatarsal. Treatment is surgical due to the high risk of pseudarthrosis, as it is an area with poor vascularisation.

- –

Stress fracture of the proximal diaphysis.

Limb injuries are very common in Accident and Emergency departments. We have to be able to describe the different injuries using the most widely used classifications, but above all we have to recognise those which can go unnoticed and lead to sequelae. We therefore need to be familiar with their particular features according to anatomical location and injury mechanism, and maintain close communication with the doctors in charge of assessing these patients.

Conventional X-ray is the initial technique of choice and often the only one. However, we can use other techniques, CT in particular, when there are implications for prognosis and management, in fractures in complex anatomical regions or with joint involvement, and to detect vascular lesions.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: A.B.B.

- 2

Study concept: A.B.B.

- 3

Study design: A.B.B.

- 4

Data collection: A.B.B., A.M.P. and M.L.R.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: A.B.B.

- 6

Statistical processing: A.B.B.

- 7

Literature search: A.B.B., A.M.P. and M.L.R.

- 8

Drafting of the article: A.B.B.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: A.B.B., A.M.P. and M.L.R.

- 10

Approval of the final version: A.B.B., A.M.P. and M.L.R.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.