To demonstrate the feasibility of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) cine sequences with compressed-sensing (CS) acceleration in the assessment of ventricular anatomy, volume, and function; and to present a fast CRM protocol that improves scan efficiency.

MethodsProspective study of consecutive patients with indication for CMR who underwent CS short-axis (SA) cine imaging compared with conventional SA cine imaging. We analysed ejection fraction (EF), end-diastolic volume (EDV), stroke volume (SV), and myocardial thickness. Two blinded independent observers performed the reading. Inter- and intraobserver agreement was calculated for all the measurements. Image quality of conventional and CS cine sequences was also assessed.

ResultsA total of 50 patients were included, 22 women (44%) with a mean age of 57.3 ± 13.2 years. Mean left ventricular EF was 59.1% ± 10.4% with the reference steady-state free precession sequences, versus 58.7% ± 10.6% with CS; and right ventricular EF with conventional imaging was 59.3% ± 5.7%, versus 59.5% ± 6.1% with CS. Mean left ventricular EDV for conventional sequences and CS were 166.8 and 165.1 ml respectively; left ventricular SV was 94.5 versus 92.6 ml; right ventricular EDV was 159.3 versus 156.4 ml; and right ventricular SV was 93.6 versus 91.2 ml, respectively. Excellent intra and interobserver correlations were obtained for all parameters (Intraclass correlation coefficient between 0.932 and 0.99; CI: 95%). There were also no significant differences in ventricular thickness (12.9 ± 2.9 mm vs 12.7 ± 3.1 mm) (p < .001). The mean time of CS SA was <40 sec versus 6–8 min for the conventional SA. The mean duration of the complete study was 15 ± 3 min.

ConclusionsCine CS sequences are feasible for assessing biventricular function, volume, and anatomy, enabling fast CMR protocols.

Demostrar la viabilidad de las secuencias cine de resonancia magnética cardiaca (RMC) aceleradas mediante detección comprimida o compressed sensing (CS) en la evaluación de la anatomía, el volumen y la función ventriculares; y presentar un protocolo de RMC rápida que mejore la eficacia de la exploración.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo de pacientes consecutivos con indicación de RMC a los que se les realizó una secuencia cine del eje corto (EC) con CS en comparación con una secuencia cine de EC convencional. Se analizaron la fracción de eyección (FE), el volumen telediastólico (VTD), el volumen sistólico (VS) y el grosor miocárdico. La lectura de las imágenes se llevó a cabo por dos observadores independientes cegados. Se calculó la concordancia intra e interobservador para todas las mediciones. También se evaluó la calidad de la imagen de las secuencias cine convencionales y con CS.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 50 pacientes, 22 mujeres (44%) con una edad media de 57,3 ± 13,2 años. La FE ventricular izquierda media fue del 59,1% ± 10,4% con las secuencias SSPF (steady-state free precession, precesión libre de estado estacionario) de referencia, frente al 58,7% ± 10,6% con CS; y la FE ventricular derecha con imágenes convencionales fue del 59,3% ± 5,7%, frente al 59,5% ± 6,1% con CS. Las medias del VTD ventricular izquierdo para las secuencias convencionales y con CS fueron de 166,8 y 165,1 ml, respectivamente; para el VS ventricular izquierdo fue de 94,5 frente a 92,6 ml; para el VTD ventricular derecho fue de 159,3 frente a 156,4 ml; y para el VS ventricular derecho fue de 93,6 frente a 91,2 ml, respectivamente. Se obtuvieron excelentes correlaciones intra e interobservador para todos los parámetros (coeficiente de correlación intraclase entre 0,932 y 0,99; IC: 95%). Tampoco hubo diferencias significativas en el grosor ventricular (12,9 ± 2,9 mm frente a 12,7 ± 3,1 mm) (p < 0,001). El tiempo medio de la exploración EC con CS fue de <40 sec frente a los 6−8 min de una EC convencional. La duración media del estudio completo fue de 15 ± 3 min.

ConclusionesLas secuencias cine CS son viables para evaluar la función biventricular, el volumen y la anatomía, lo que permite protocolos rápidos de RMC.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is the imaging technique of choice to assess the anatomy, function, and tissue characteristics of the heart in a single scan.1,2 Due to its many advantages, including the absence of ionizing radiation, its multiplanar capacity with wide fields of view, and the possibility of characterizing the entire myocardium in a noninvasive manner, it is the reference method recommended in the guidelines of the different cardiological societies to evaluate increasingly varied and complex clinical scenarios.3–6 CMR has proved to be clinically useful for the assessment of heart failure, cardiomyopathies, ventricular arrhythmias, myocarditis, or myocardial infarction.7–9

Many of the CMR sequences that have appeared in recent years have been consecutively added to routine protocols for the study of patients with cardiovascular pathology. This has meant that, despite the availability of technical advances that accelerate the acquisition and improve the quality of CMR images, scan times are often still long and perpetuate the idea that CMR is an expensive and inaccessible imaging tool.8,9

However, given the increase in the clinical indications for this technique and the capital implication that its results may have on patient management, a considerable expansion in the number of CMRs to be performed is expected, so it is recommended that efforts be devoted to simplifying and streamlining study protocols that also maintain optimal diagnostic accuracy.10–13

One of the most recent acceleration techniques for CMR sequences is compressed sensing (CS), based on k-space random undersampling, together with a noise reduction algorithm that employs sparse representation in a non-linear iterative reconstruction process. The objective of CS is to significantly reduce acquisition time while minimizing the impact on image quality. CS is available in many of the late-generation conventional scans.14–16

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to evaluate the feasibility of cine sequences with CS acceleration in the evaluation of the function, volume, and anatomy of both ventricles compared to conventional sequences; and, on the other hand, to present a fast protocol, adjusted to clinical practice guidelines, which allows optimal cardiovascular diagnosis and improves efficiency of the scans and patient accessibility to CMR.

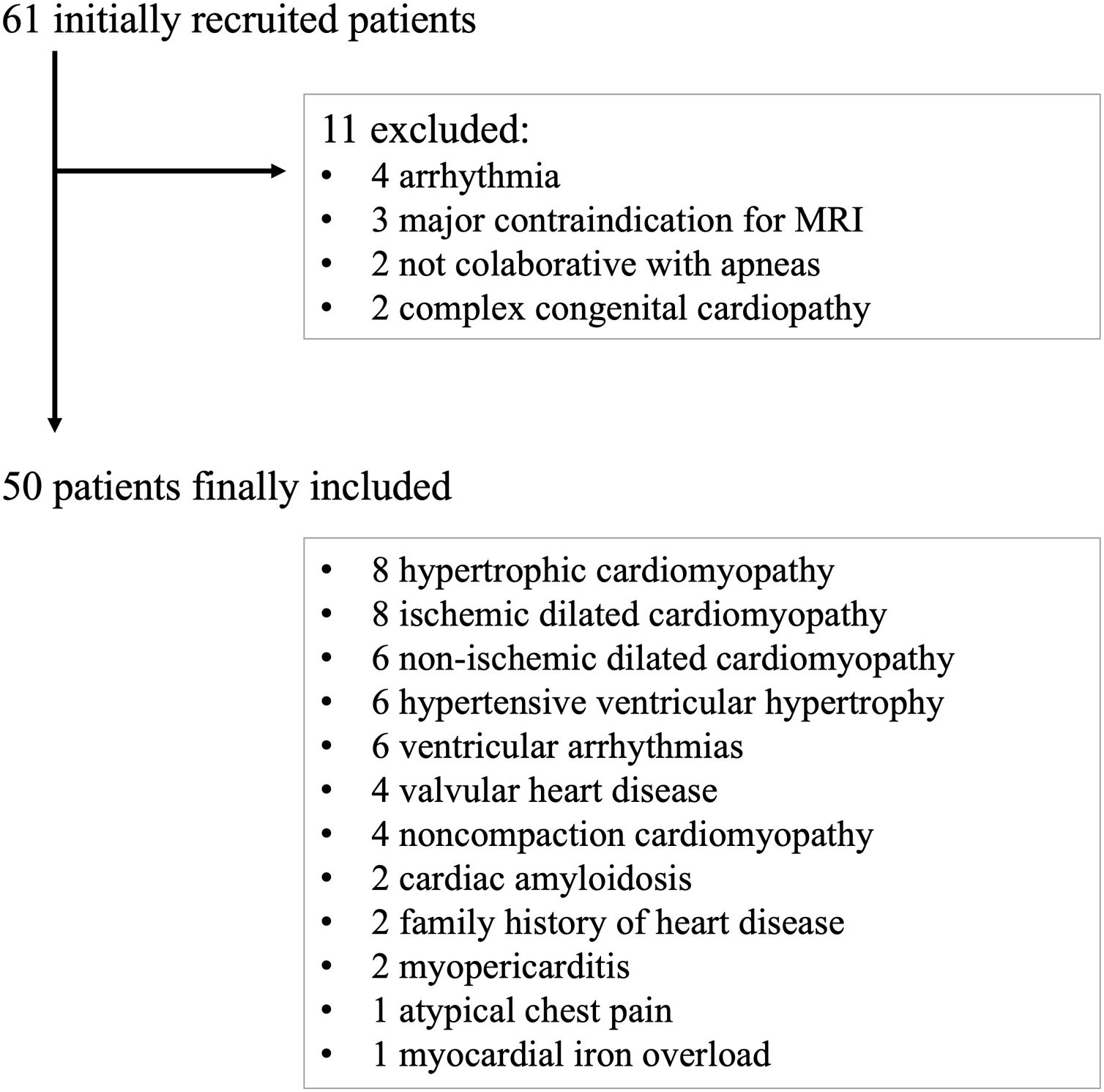

MethodsPatientsA prospective observational study was carried out, with consecutive recruitment of patients referred to our center for intravenous (IV) contrast-enhanced CMR by clinical indication, between January 2021 and March 2021. All patients signed a double consent form accepting to undergo CMR and to be included in the study. Research consent was obtained from the local Ethics Committee (*blinded for anonymization*). A total of 61 patients were included in the study, 11 of whom presented some exclusion criteria.

The exclusion criteria were detection of arrhythmias in the vectorcardiogram that prevented retrospective acquisition imaging (4 patients), any contraindication for performing CMR (3 patients), lack of patient collaboration for maintaining apneas, requiring free-breathing CMR sequences (2 patients), or complex congenital heart disease that substantially modified the cine axis orientation (2 patients). A final cohort of 50 patients with its clinical diagnosis is summarized in Fig. 1.

Image acquisitionAll scans were performed on two 1.5 T MRI scans with the same technical characteristics (MAGNETOM Sola, Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany), with a 30-channel phase-array coil, with vectorcardiographic recording through skin electrodes. The imaging protocol was based on the SCMR recommendations6 and systematically included scouts with balanced steady state free precession sequences (SSFP), and a native T1 mapping (short axis and four chambers axis) before IV contrast. After IV contrast administration of a total dose of 0.15 mmol/kg of gadolinium (Dotarem, Bayer Pharma AG, Germany), 2D functional cine SSFP retrospectively cardiac-gated Cartesian sequences were acquired in the long axis (LA) (2-, 3-, and 4-chamber planes). A base-to-apex short-axis (SA) stack to cover the entire volume of both ventricles with CS acceleration, multisection retrospectively cardiac-gated Cartesian sequence, was obtained during two breaths hold at end-expiration and with complete cardiac cycle covered. The acquisition duration was 3 R-R intervals per section, being the first heartbeat used for signal preparation to reach the steady state, and the 2 other heartbeats employed for data acquisition. Original settings of the CS given by the imager vendor, attending to fixed and intertwined parameters, were not modified to ease reproducibility.

Phase-sensitive inversion-recovery (PSIR) 2D late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) SSFP sequences were then performed in the LA and SA; followed by post-gadolinium T1 mapping for extracellular volume calculation.17,18

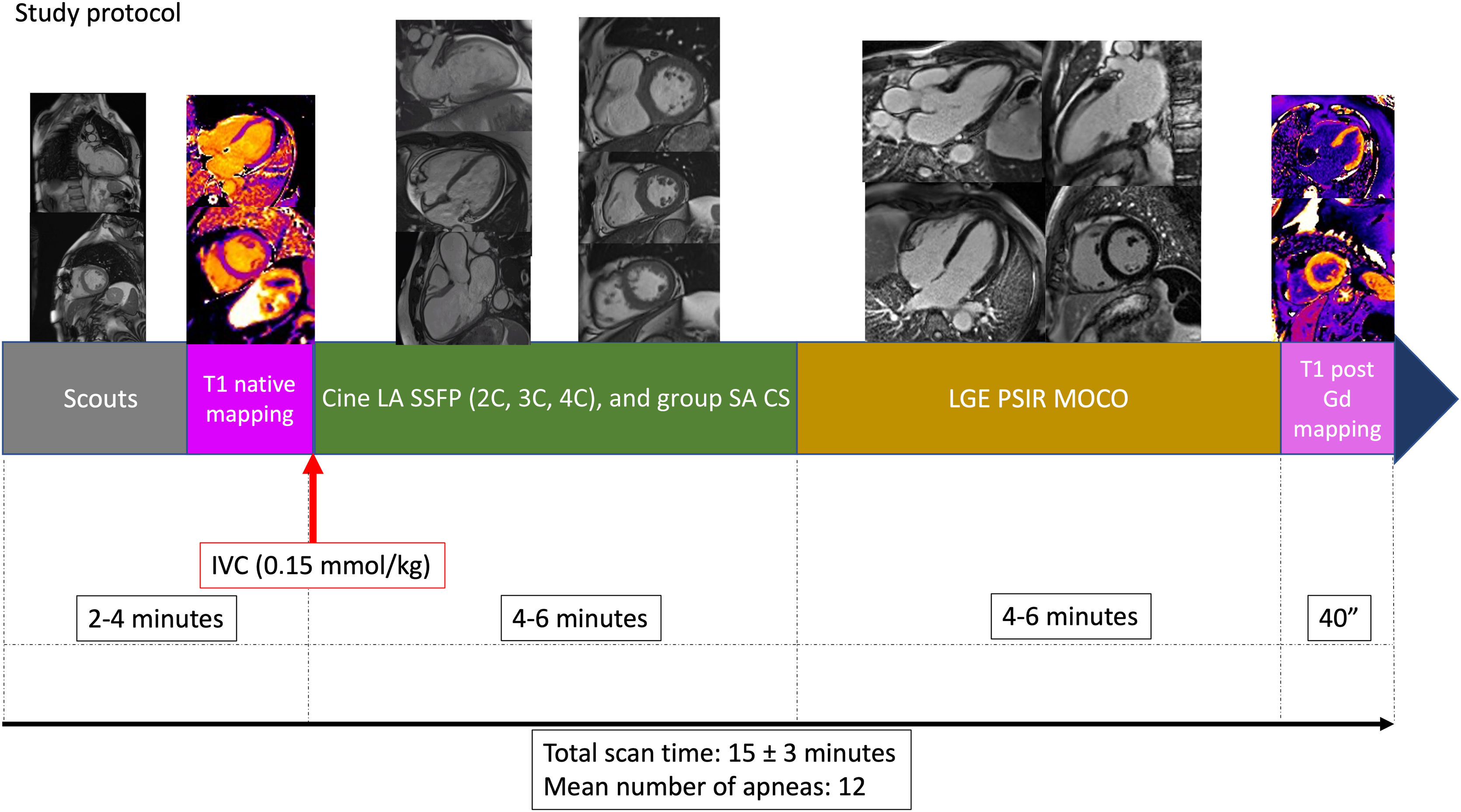

To conclude, a SA stack was performed on conventional multisection 2D SSFP base-to-apex cine sequences of one end-expiration apnea per section, retrospectively cardiac-gated Cartesian sequence, which served as a gold standard to compare the accelerated sequences. Fig. 2

Fast CMR protocol (excluding conventional sequences used as reference standard for this research). After the scouts and the native T1 mapping, the intravenous contrast (IVC) is inyected, followed by long axis (LA) cine balanced steady state free precession (SSFP): two chamber (2C), three chamber (3C), and four chamber views (4C); and the short axis (SA) stack with compressed-sensing (CS) acceleration. The next step is the acquisition of the late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequences with phase-sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) images, with movement correction (MOCO), and finally the post-Gadolinium (Gd) T1 mapping. Mean total study time and number of apneas are detailed at the bottom.

CS acceleration was used only in the SA stack cine, allowing significant reduction in time and number of apneas. Single long axis cines were performed with conventional acquisition, as CS would not decrease number of apneas and equilibrium phase for LGE imaging requires at least 5−6 min.

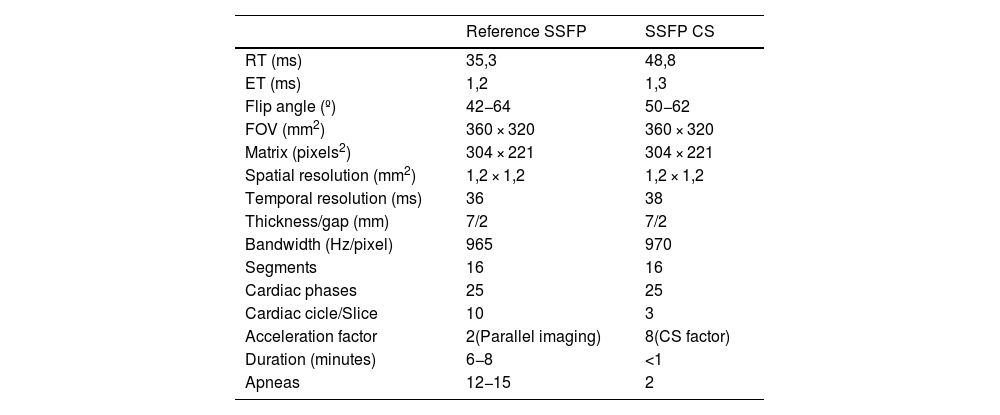

The technical characteristics of CS and conventional sequences are summarized in Table 1.

Technical parameters of SSFP reference sequences and CS accelerated sequences for ventricular short-axis cine imaging.

| Reference SSFP | SSFP CS | |

|---|---|---|

| RT (ms) | 35,3 | 48,8 |

| ET (ms) | 1,2 | 1,3 |

| Flip angle (º) | 42−64 | 50−62 |

| FOV (mm2) | 360 × 320 | 360 × 320 |

| Matrix (pixels2) | 304 × 221 | 304 × 221 |

| Spatial resolution (mm2) | 1,2 × 1,2 | 1,2 × 1,2 |

| Temporal resolution (ms) | 36 | 38 |

| Thickness/gap (mm) | 7/2 | 7/2 |

| Bandwidth (Hz/pixel) | 965 | 970 |

| Segments | 16 | 16 |

| Cardiac phases | 25 | 25 |

| Cardiac cicle/Slice | 10 | 3 |

| Acceleration factor | 2(Parallel imaging) | 8(CS factor) |

| Duration (minutes) | 6−8 | <1 |

| Apneas | 12−15 | 2 |

CS: compressed sensing; ET: echo time; FOV: field of view; RT: repetition time; SD: standard deviation; SSFP: steady state balanced free precession.

The images were evaluated by 2 observers blinded to the diagnosis, with experience in CMR (7 and 10 years of CMR reading, respectively). The first observer analyzed the images of the conventional and CS-accelerated sequences, with a week separation between both readings to avoid memory bias. The second observer independently evaluated the CS-accelerated images. Both readers performed postprocessing of the images using specific software (QMass MR 7.5, Medis, The Netherlands) that automatically delimits the myocardial contours of each cine image, with subsequent manual adjustment.19 Quantitative values of ejection fraction, end-diastolic volume and stroke volume of both ventricles were recorded. The two observers quantified the maximum LV myocardial thickness in end-diastole phase in both conventional and accelerated cine SA sequences.

The clinical characteristics of the patients were also collected.

The quality of the cine images was subjectively evaluated on a 4-point scale, independently between the two readers, both for standard SSFP and CS: (1) poor (not valid for clinical diagnosis); (2) fair (useful for clinical diagnosis, but with slight-moderate artifacts); (3) good (valid for clinical diagnosis, without artifacts, but with discrete spatial resolution or signal-to-noise ratio); (4) very good (image of optimal quality).

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Qualitative baseline characteristics are expressed as frequency (%). Agreement between accelerated and conventional sequence measurements was assessed by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), Bland-Altman plots and linear regression analysis. Concordance was considered poor, moderate, good, or excellent for ICC < 0.50, 0.50–0.75, 0.75–0.90, and >0.90, respectively. For the Bland-Altman analysis, no significant systematic bias was assumed if the 95 % CI for the mean difference between measurements contained the value 0. Agreement between readers for subjective image quality was analyzed using weighted kappa with the level of agreement as follows: κ < 0 poor; κ = 0.01–0.2 slight; κ = 0.21–0.4 fair; κ = 0.41–0.6 moderate, κ = 0.61–0.8 substantial; κ > 0.81 almost excellent. Student's t-test was used to compare means of quantitative parameters, statistical significance was set at p < .05. All statistical analyses and graphs were generated using R (version 4.1.2: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

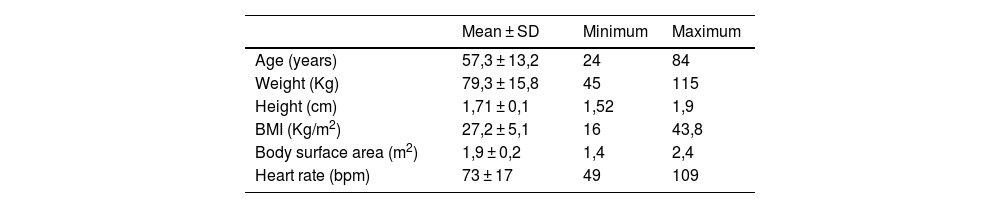

ResultsStudy populationOf the final 50 individuals, 22 were women (44%), with a mean age of 57.3 ± 13.2 years. The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2.

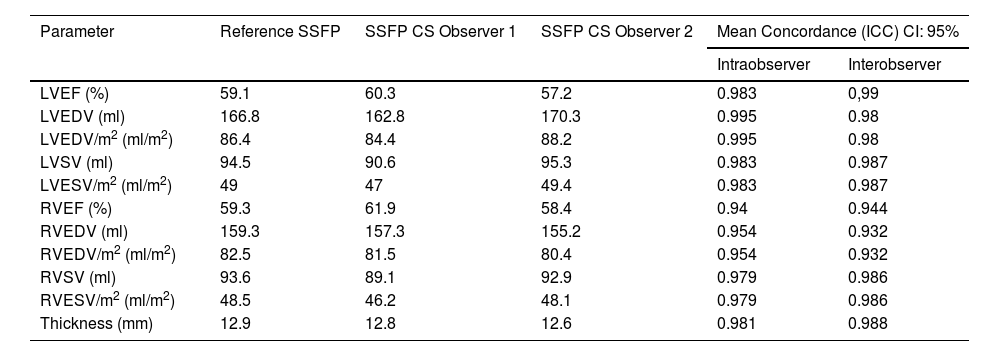

CS accuracy in the evaluation of ventricular anatomy, volume, and functionConsidering conventional SSFP cine as the standard reference method, no significant differences were observed with respect to EF, EDV or SV of both ventricles, when compared with CS. Mean LVEF was 59.1% ± 10.4% with the reference sequences, versus 58.7% ± 10.6% with CS (mean of both readers); and RVEF was 59.3% ± 5.7% and 59.5% ± 6.1%, respectively, with excellent ICC (0.983−0.99, and 0.934−0.964; CI: 95%). Mean LVEDV, LVSV, RVEDV and RVSV were 166.8/165,1, 94.5/92,6, 159,3/156,4 and 93,6/91,2 ml, for conventional/CS, respectively; and mean LVSV/m2, LVEDV/m2, RVEDV/m2 and RVESV/m2 were 86.4/85.5, 49/48, 82.6/81, 48.5/47,3 ml/m2, respectively (ICC: 0.98−0.99; 0.95−0.98; 0.932−0.978; 0.971−0.982; CI: 95%).

There were also no significant differences in ventricular thickness, which was 12.9 ± 2.9 mm and 12.7 ± 3.1 mm, with reference and CS sequences (p < 0.001). Numeric results are summarized in Table 3.

Morphology and functional parameters evaluated by reference SSFP sequences and accelerated CS sequences.

| Parameter | Reference SSFP | SSFP CS Observer 1 | SSFP CS Observer 2 | Mean Concordance (ICC) CI: 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraobserver | Interobserver | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 59.1 | 60.3 | 57.2 | 0.983 | 0,99 |

| LVEDV (ml) | 166.8 | 162.8 | 170.3 | 0.995 | 0.98 |

| LVEDV/m2 (ml/m2) | 86.4 | 84.4 | 88.2 | 0.995 | 0.98 |

| LVSV (ml) | 94.5 | 90.6 | 95.3 | 0.983 | 0.987 |

| LVESV/m2 (ml/m2) | 49 | 47 | 49.4 | 0.983 | 0.987 |

| RVEF (%) | 59.3 | 61.9 | 58.4 | 0.94 | 0.944 |

| RVEDV (ml) | 159.3 | 157.3 | 155.2 | 0.954 | 0.932 |

| RVEDV/m2 (ml/m2) | 82.5 | 81.5 | 80.4 | 0.954 | 0.932 |

| RVSV (ml) | 93.6 | 89.1 | 92.9 | 0.979 | 0.986 |

| RVESV/m2 (ml/m2) | 48.5 | 46.2 | 48.1 | 0.979 | 0.986 |

| Thickness (mm) | 12.9 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 0.981 | 0.988 |

CS, compressed sensing; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVSV, left ventricular stroke volume; RVEDV, right ventricular end-diastolic volume; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; RVSV, right ventricular stroke volume; SSFP, balanced free precession steady state.

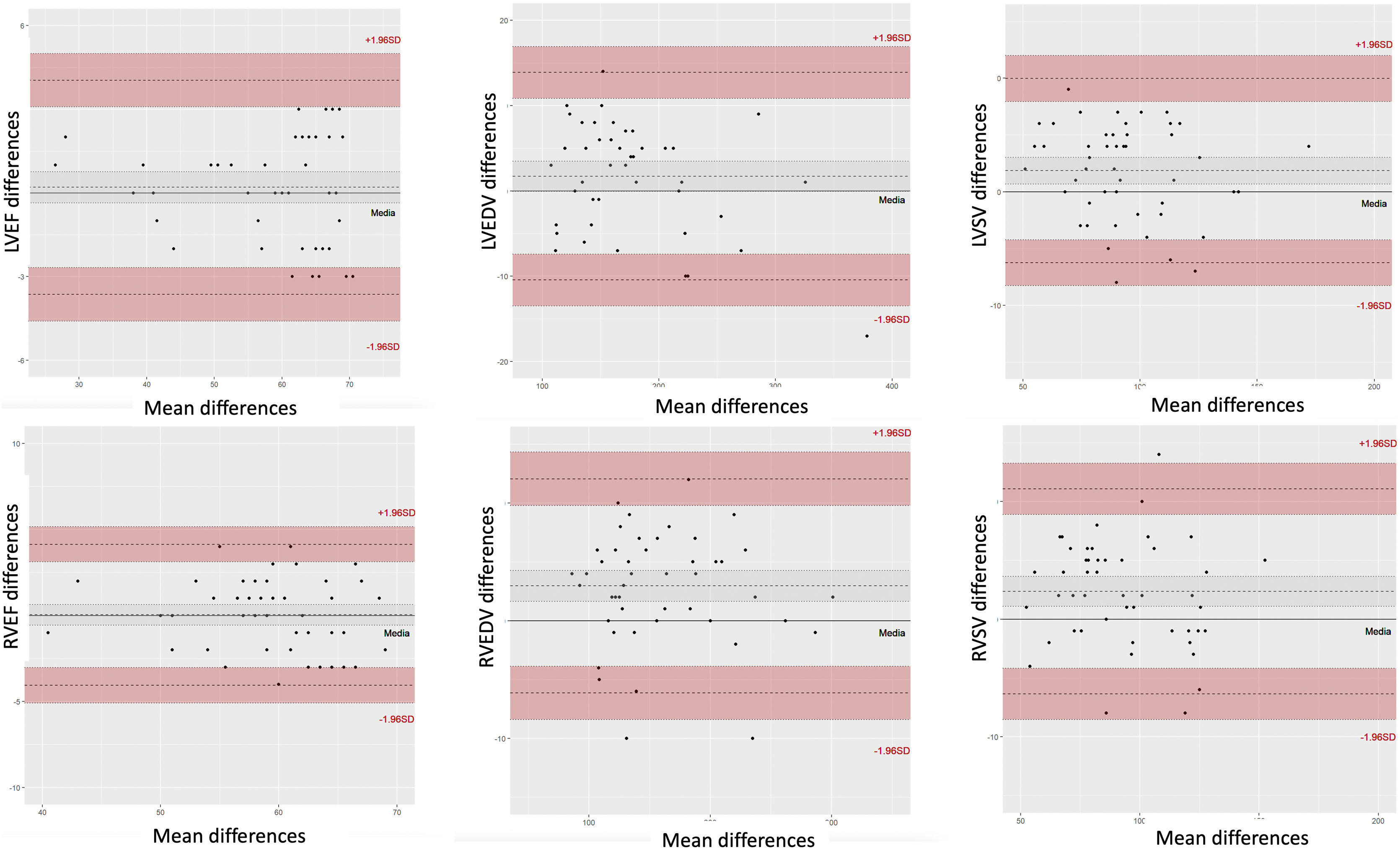

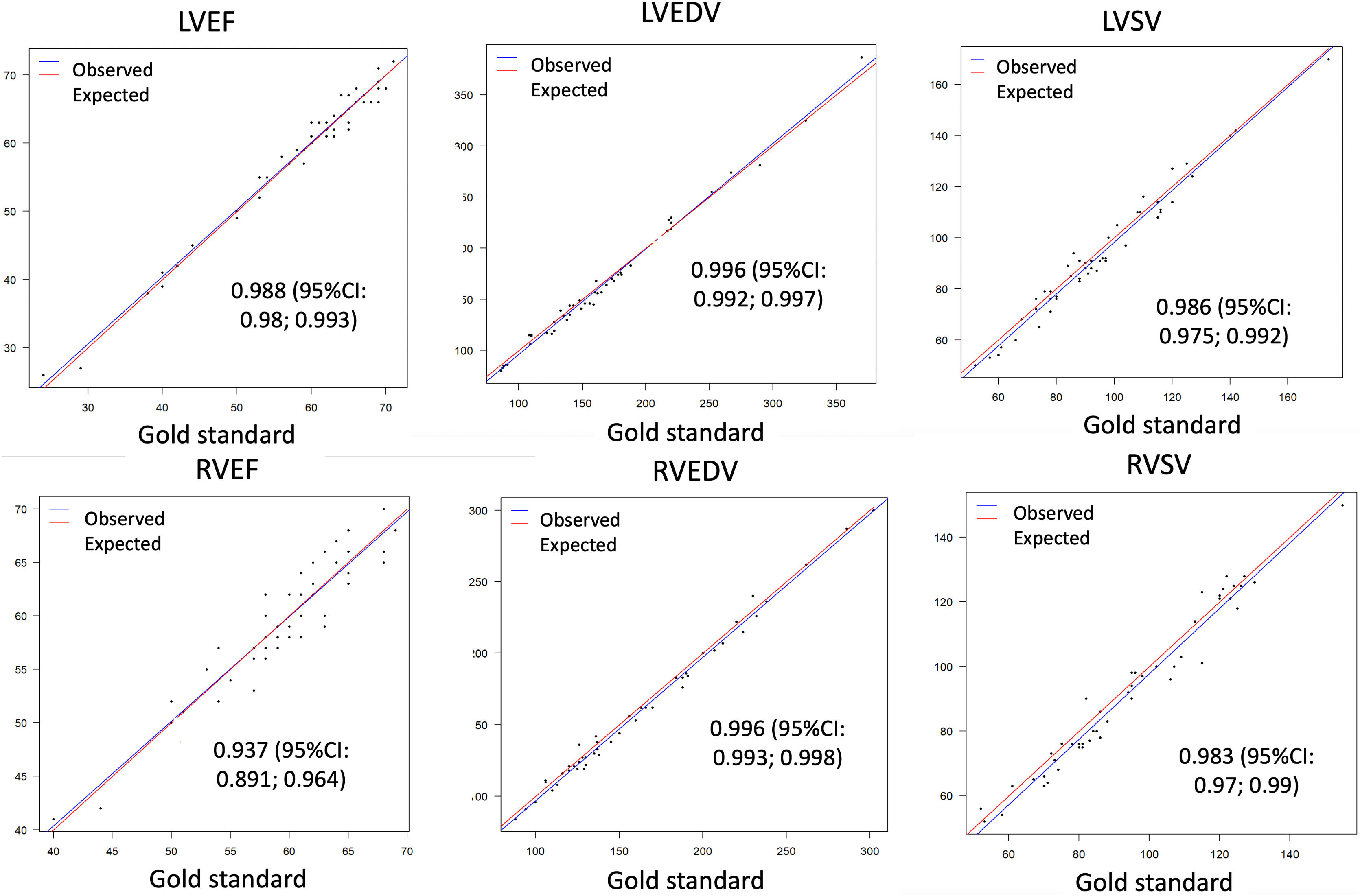

Bland-Altman analysis and linear regression, both intra- and interobserver, showed excellent correlation for all parameters (Figs. 3 and 4).

Bland and Altman correlation plots of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF), left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricular sistolic volume (LVSV), right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF), right ventricular end-diastolic volume (RVEDV) and right ventricular sistolic volume (RVSV) quantification between the mean CS values from the two observers and the conventional SSFP for reference.

Linear regression plots for correlation analysis of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF), left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricular sistolic volume (LVSV), right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF), right ventricular end-diastolic volume (RVEDV) and right ventricular sistolic volume (RVSV) quantification between the mean CS values from the two observers and the conventional SSFP for reference (gold standard), with confident intervals (CI).

The mean duration of the SA cine imaging with CS was less than 40 seconds in two apneas; whereas in conventional sequences the acquisition lasted between 6 and 8 min, in 12−15 apneas (one apnea per slice, to include the entire ventricular volume).

The mean acquisition duration of the study, excluding conventional sequences used as a standard reference method, was 15 ± 3 min.

An average of 12 ± 2 apneas were used to complete the entire study, including the initial scout sequences, disregarding conventional reference sequences.

All acquisitions performed with both sequences were rated as diagnostic. The mean image quality was good, with a mean of 3.2 for CS cine and 3.4 for conventional cine imaging, with no statistically significant differences (p = 0.34). For conventional SSFP: 22% of patients were rated 4, 62% rated 3; 16% rated 2. For CS cine imaging: 19% rated 4; 59 % rated 3; 22% rated 2. Inter-reader agreement for subjective image quality was almost excellent for both techniques (conventional SSFP κ = 0.842, CS κ = 0.857) (Fig. 5).

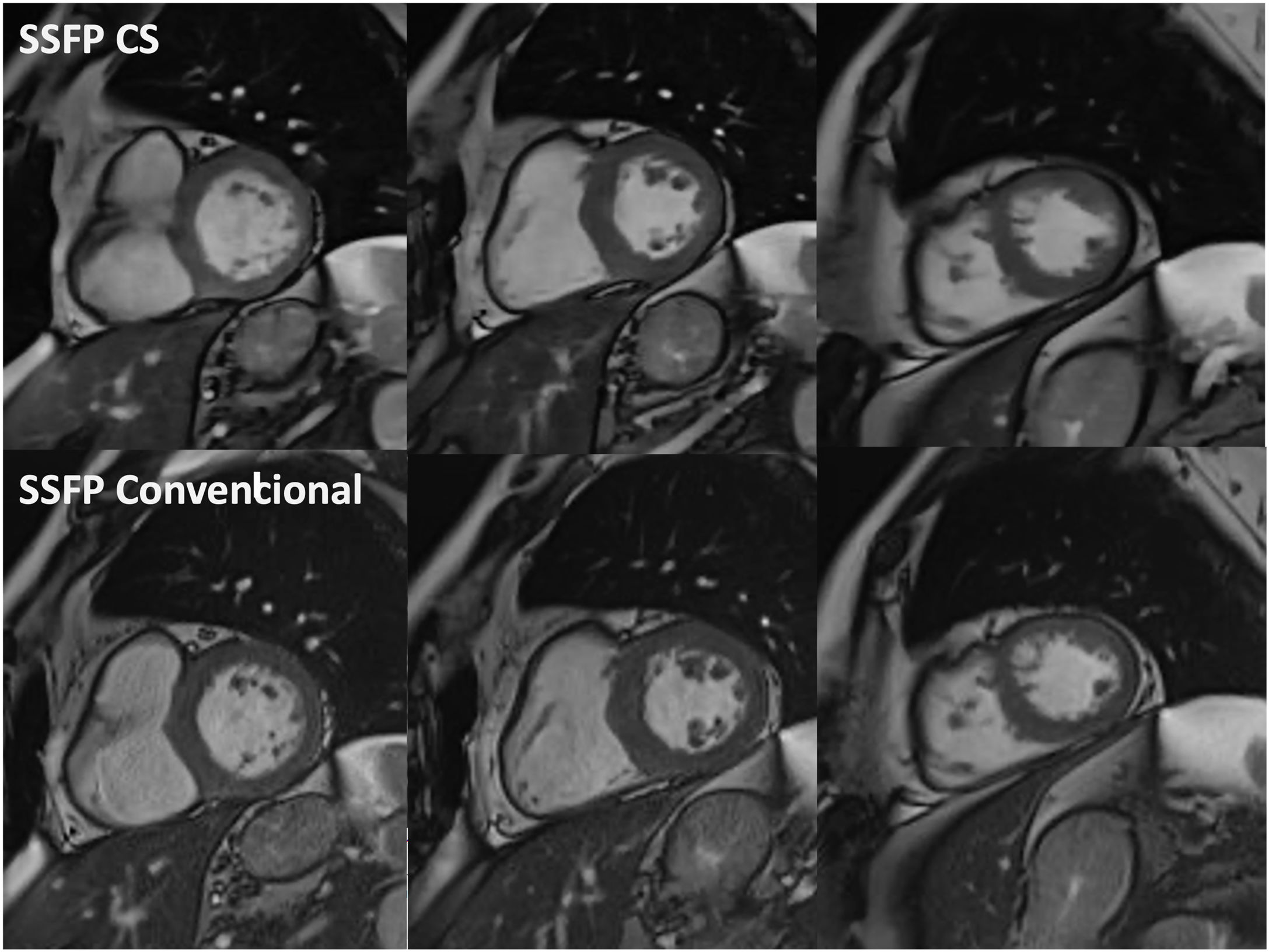

Example of cine balanced steady state free precession (SSFP) imaging with compressed sensing (CS) sequences in end-diastole (top row) in basal, mid, and apical short axis (from left to right), versus conventional SSFP counterpart images (bottom row). Notice that spatial resolution, contrast resolution and image quality of both rows are similar.

A mean of 1.3 apneas per study were repeated for respiratory artifacts in the conventional SSFP scan, compared to 0.4 apneas in the CS scan (p < 0.001).

DiscussionOur study demonstrates the feasibility of cine sequences with CS acceleration to assess ventricular anatomy, function, and volume in clinical practice, showing similar results to conventional sequences, with high intra- and interobserver agreement. CS imaging shows good quality, similar to that of conventional sequences. These accelerated sequences facilitate the development of fast CMR protocols that can improve scan availability and reduce costs.

Our strategy is in line with recent efforts by different societies and cardiac imaging groups to simplify CMR studies and make this imaging modality a central and widespread pillar of the diagnosis of patients with cardiovascular pathology.12,20–22

Our findings are consistent with recent works on CS acceleration techniques for ventricular evaluation.16,23–27 All of them support the usefulness of these acquisitions, obtaining results with good reproducibility and image quality similar to ours. Specifically, Vermersch et al. found that real-time CS sequences provide reliable measurements of both left and right ventricles with high inter and intraobserver reliability.16

In addition, unlike some previous research studies evaluating these sequences, we employed a retrospective acquisition without real-time, which replicates and resembles the scheme of our conventional SSFP sequences commonly used in clinical practice.

However, it is not enough to have fast and high-quality image acquisitions. It is also necessary to integrate them into standardized and homogeneous protocols that allow for efficient examinations. To our knowledge, this is the first study that describes a fast CMR protocol with early introduction of iv contrast, and acquisition of cine sequences in the time interval until the equilibrium state necessary for LGE evaluation. Improving accessibility to CMR involves not only having fast sequences but also developing protocols that take advantage of that speed.

Our study evaluates CS acceleration with retrospective acquisition in patients in daily clinical practice, with 1.5 T scan, and with near real-time reconstruction imaging that do not interfere with the normal workflow. This means that there is no need for a paradigm shift to implement acceleration sequences, but rather, with conventional scans, standard CMR can be performed in about 15 min.

The CS cine sequences avoid the need to use an apnea of about 8–15 seconds per slice, for about 12−15 slices to cover the entire ventricular volume, performing it in our case only in two apneas.

Furthermore, the use of CS acceleration in sequences reduces the temporal variability at the beginning of LGE sequences. This simplifies the need for calculating the optimal inversion time (Look-Locker), allowing for satisfactory myocardial signal nulling in the majority of studies using a predefined inversion time. We use motion-corrected 2D LGE PSIR SSFP (MOCO) sequences, which dampen the heterogeneity of myocardial saturation up to 100 ms deviations from the optimal inversion time and are acquired in free breathing, avoiding breathing artifacts due to patient fatigue at the end of the test.28–30

Although we have not compared the accuracy in atrial volume calculation as recently conducted by Altmann et al.,31 we assume that our results could be extrapolatable, due to the good image quality and interobserver agreement, in case their quantification with accelerated CS sequences is required.

This study has limitations. First, we used 2D sequences that require precise planning of the cardiac axis, and it is possible that the use of 3D sequences could be generalized soon, although this volumetric acquisition is scarcely extended in clinical practice at the moment. This supports that rapid protocols such as the one we present can be implemented without great effort in many CMR centers. Second, arrhythmic and noncooperative patients were excluded due to the retrospective acquisition of our CS cine sequences, but prospective and real time acquisitions with CS are available and may be useful in these patients, and could be evaluated in future studies. Third, we only evaluate CS acceleration for the SA stack cine, but it may be useful for long axis cines and LGE imaging in adequate settings.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate the feasibility of CS-accelerated cine SSFP sequences to accurately assess the function, volume, and anatomy of both ventricles, comparable to conventional sequences and with high image quality. They also demonstrate the possibility of including these accelerated sequences in fast protocols that improve availability of CMR and facilitate patient accessibility and comfort.

FundingThis research has not received specific aid from public sector agencies, commercial sectors or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

AcknowledgementsMany thanks to the entire group of nurses, imaging technicians, assistants and secretaries of the MRI unit at Osatek Deusto, without whom this work could not have been carried out.

Authorship/collaboratorsStudy conception: ROP, NHA, ACA, DZS.

Study design: ROP, NHA.

Data acquisition: ROP, DZS.

Data analysis and interpretation: ROP, DZS.

Statistical processing: SPF.

Drafting of the manuscript: ROP, ACA, CDS.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: NHA, ACA, DZS, SPF, CDS.

Approval of the final version: ROP. NHA, ACA, DZS, SPF, CDS.