Pneumatosis intestinalis is a radiological finding characterized by the presence of gas in the bowel wall that is associated with multiple entities. Our aim is to know its incidence in lung transplant patients, its physiopathology and its clinical relevance.

MethodsA search of patients with pneumatosis intestinalis was performed in the database of the Lung Transplant Unit of our hospital. The presence of pneumatosis after transplantation was confirmed in all of them and relevant demographic, clinical and imaging variables were collected to evaluate its association and clinical expression, as well as the therapeutic approach after the findings.

ResultsThe incidence of pneumatosis intestinalis after lung transplantation in our center was 3.1% (17/546), developing between 9 and 1270 days after transplantation (mean, 198 days; median 68 days). Most of the patients were asymptomatic or with mild symptoms, without any major analytical alterations, and with a cystic and expansive radiological appearance. Pneumoperitoneum was associated in 70% of the patients (12/17). Conservative treatment was chosen in all cases. The mean time to resolution was 389 days.

ConclusionPneumatosis intestinalis in lung transplant patients is a rare complication of uncertain origin, which can appear for a very long period of time after transplantation. It has little clinical relevance and can be managed without other diagnostic or therapeutic interventions.

La neumatosis intestinal es un hallazgo radiológico caracterizado por la presencia de gas en la pared del intestino que se asocia a múltiples entidades. Nuestro objetivo es conocer su incidencia en pacientes con trasplante pulmonar, su fisiopatología y su relevancia clínica.

Material y métodosSe realizó una búsqueda de pacientes con neumatosis intestinal en la base de datos de la Unidad de Trasplante Pulmonar de nuestro hospital. En todos ellos se confirmó la presencia de neumatosis intestinal tras el trasplante y se recogieron variables demográficas, clínicas y de imagen relevantes para evaluar su asociación y expresividad clínica, así como la actitud terapéutica tras los hallazgos.

ResultadosLa incidencia de neumatosis intestinal postrasplante pulmonar en nuestro centro fue del 3,1% (17/546), desarrollándose entre 9 y 1270 días tras el trasplante (media, 198 días; mediana 68 días). La mayoría de los pacientes estaban asintomáticos o con síntomas leves, sin grandes alteraciones analíticas, y con un aspecto radiológico quístico y expansivo. Asoció neumoperitoneo en un 70% (12/17). Se optó por un tratamiento conservador en todos los casos. El tiempo medio hasta la resolución fue de 389 días.

ConclusiónLa neumatosis intestinal en pacientes con trasplante pulmonar es una complicación rara, de origen incierto, que puede aparecer en un periodo de tiempo muy amplio tras el trasplante. Tiene escasa relevancia clínica y puede manejarse sin otras intervenciones diagnósticas ni terapéuticas.

Pneumatosis intestinalis is a radiological finding characterised by the presence of gas in the wall of the small or large intestine. It is associated with multiple entities, ranging from benign to life-threatening conditions such as ischaemia, intestinal obstruction and necrotising enterocolitis.1 Benign pneumatosis intestinalis is a rare finding, detected incidentally in imaging tests, usually in immunosuppressed patients with solid organ transplantation, graft-versus-host disease, asthma or COPD or as an endoscopy complication.2 Its occurrence in adult lung transplant patients has been reported as a benign and conservatively managed entity both in isolated cases2–12 and in short series.13–15

Our objective is to describe the incidence of this complication in lung transplant patients, describe its associations and assess its clinical relevance.

Material and methodsA total of 546 adult lung transplants were performed at our university hospital between January 2011 and October 2022 (141 months). The patients were selected by a search (pneumatosis intestinalis or pneumatosis coli or pneumatosis) in the hospital’s Lung Transplant Unit database.

In all patients, the presence of pneumatosis intestinalis (considered as the episode) after transplantation was confirmed in their clinical history, and the following relevant variables were gathered to evaluate association and clinical expression:

- –

Demographic variables: age, sex, indication and type of transplant (single-lung, double-lung or heart-lung), post-surgical complications (yes/no and which).

- –

Time from transplant to the episode (days).

- –

Clinical data at the time of the episode: abdominal signs and symptoms, vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, O2 saturation and temperature), signs of rejection (yes/no and which), evidence of pulmonary or gastrointestinal infection, blood tests (white blood cell count, CRP, lactate, bicarbonate, amylase pH), immunosuppressive medication (type and dose) and whether the patient was hospitalised.

- –

Imaging data: indication for the test, imaging technique used to diagnose pneumatosis, radiological findings (presence and distribution of air), pneumoperitoneum, portal or mesenteric venous pneumatosis, free fluid, pneumobilia, indication for other imaging tests.

- –

Therapeutic approach: medical treatment, surgical treatment, time to resolution of pneumatosis.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe (registration number: 2022-925-1).

ResultsOf the 546 lung transplant patients, 17 (3.1%, Fig. 1) with pneumatosis intestinalis were identified. The main clinical and radiological data are presented in Table 1. Of the 17 patients included, 12 were male and 5 female, with a mean age of 51 years (range 21–66 years). The indications for transplantation were pulmonary fibrosis (6 cases), emphysema (4 cases), cystic fibrosis (3 cases), congenital heart disease with pulmonary hypertension (2 cases), primary ciliary dyskinesia (1 case) and pneumoconiosis (1 case). Transplantation was either single-lung (n = 4), double-lung (n = 11) or heart-double lung (n = 2). Some type of post-surgical complication was observed in 11 patients with pneumatosis (65%).

Main clinical and radiological data of our patient series.

| Patient (inpatient or outpatient) | Age, sex | Indication; type of Tx | Postoperative complications | Time from Tx to PI (days) | Symptoms; signs | Vital signs (BP, HR, O2 sat., Temp.) | Laboratory | Signs of rejectiona | Signs of pulmonary or GI infection | Immunosuppressant medication (drug, dose/24 h and blood levels) | Type and indication of the first test in which PI was diagnosed | Radiological findings | Distribution of PI in abdomino-pelvic CT scans | Attitude and time to resolution (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Outpatient | 51, F | Congenital heart disease (VSD) and pulmonary hypertension; cardiopulmonary therapy | IMV re-intubation; tracheostomy; PTN; haemorrhagic CVA | 289 | No pain; abdominal distension | BP 145/87 mmHg; HR 87 bpm; O2 sat. 99%; Temp. 36.5 °C | Normal | Clinical | No | Methylprednisolone (16 mg); cyclosporine (375 mg; 291.5 ng/mL) MM (1000 mg; 0.8 µg/mL, infratherapeutic) | Abdomino-pelvic CT scan; referred from another hospital for pneumoperitoneum | Pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum | Ascending colon | Indication AP CT scan; IC to GS; expectant management, no Qx; / |

| 2 Inpatient | 49, F | Primary ciliary dyskinesia; double-lung Tx | No | 875 | No pain; physical examination normal | BP 113/74 mmHg; HR 66 bpm; O2 sat. 96%; Temp. 36.8 °C | Leukocytosis (12.26 × 103/µL) with neutrophilia (10.42 × 103/µL); CRP 160 mg/L | No | Yes, viral pneumonia | Prednisone (10 mg); azathioprine (100 mg); tacrolimus (8 mg; 12.2 ng/mL) | Chest abdomen and pelvis CT scan; assessment of septic foci | Pneumatosis intestinalis, free fluid viral pneumonia | Caecum | No CT scan; IC to DM (Digestive Medicine); domperidone treatment, no Qx; 119 days |

| 3 Outpatient | 39, F | Congenital heart disease (ASD) and PHT; heart and double-lung Tx | PTE; prolonged NIMV; bacterial pneumonia | 118 | No pain; abdominal distension | BP 123/83 mmHg; HR 75 bpm, O2 sat. 98%, Temp. 36.6 °C | Normal | No | No | Prednisone (10 mg), tacrolimus (16 mg; 11.2 ng/mL); MM (360 mg; 0.7 µg/mL, infratherapeutic) | Chest CT scan; previous PTE | Pneumatosis intestinalis in hepatic flexure | / | No CT scan, no IC; expectant management, no Qx; 136 days |

| 4 Inpatient | 56, M | UIP-type pulmonary fibrosis + PHT; double-lung Tx | CMV replication; multiple FBS; aspergillus infection | 48 | No pain; physical examination normal | BP 107/70 mmHg; HR 81 bpm; O2 sat. 98%; Temp. 35.4 °C; | Normal | No | No | Methylprednisolone (20 mg); tacrolimus (4 mg; 10.1 ng/mL); MM (3000 mg; 3 µg/mL) | Chest CT scan; assessment of transplant status | Pneumatosis intestinalis in hepatic flexure | / | No CT scan, no IC; expectant management, no Qx; 154 days |

| 5 Outpatient | 39, M | Cystic fibrosis; double-lung Tx | No | 1270 | No pain; physical examination normal | / | Normal | No | No | Prednisone (10 mg), tacrolimus (3 mg; 7.3 ng/mL); everolimus (3 mg; 8.8 ng/mL) | Chest CT scan; suspected bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome | Pneumatosis intestinalis hepatic flexure and pneumoperitoneum | / | No CT scan, no IC; expectant management, no Qx; 1379 days |

| 6 Inpatient | 21, M | Cystic fibrosis; double-lung Tx | Prolonged IMV; left-side phrenic nerve paralysis; PEG due to gastroparesis | 68 | No pain; abdominal distension | BP 128/94 mmHg; HR 104 bpm; O2 sat. 96% Temp. 36 °C | CRP 48.7 mg/L | Clinical | No | Methylprednisolone (20 mg); tacrolimus (5 mg; 8.5 ng/mL); MM (1500 mg; 3.4 µg/mL) | Chest CT scan; assess atelectasis detected on X-ray | Pneumatosis intestinalis transverse colon | / | No CT scan, no IC; expectant management, no Qx; 105 days |

| 7 Inpatient | 40, M | Pneumoconiosis (silicosis); right-sided one-lung Tx | No | 64 | No pain; physical examination normal | BP 97/57 mmHg; HR 86 bpm; O2 sat. Temp. 36.7 °C | Leukocytosis (17.47 × 103/µL) with neutrophilia (16.48 × 103/µL); CRP 43.9 mg/L | Clinical | Yes, cough and pleural effusion | Methylprednisolone (40 mg); tacrolimus (3 mg; 23 ng/mL, overdosage); MM (1000 mg; 3.4 µg/mL) | Abdomino-pelvic CT scan; desaturation, leukocytosis and normal general condition | Pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum | Ascending colon and hepatic flexure | Indication AP CT scan; IC to GS; expectant management, no Qx; 215 days |

| 8 Outpatient | 58, M | Emphysema-type COPD; double-lung Tx | Bronchial stenosis; persistent air leak; multiple FBS | 169 | Vomiting, increased stool rhythm; physical examination normal | BP 136/66 mmHg; HR 67 bpm; O2 sat. 98%; Temp. 36.2 °C | Normal | No | No | Prednisone (5 mg); tacrolimus (2 mg; 10.9 ng/mL); MM (1000 mg; 0.9 µg/mL) | Chest CT scan; assess airway stenosis | Pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum | Caecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse, splenic flexure, descending, sigmoid, and rectum | Indication AP CT scan; IC to DGM; expectant management, no Qx; indication CT scan in 1–3 months; 75 days |

| 9 Outpatient | 61, M | UIP-type pulmonary fibrosis; right-lung Tx | No | 38 | No pain; physical examination normal | BP 115/66 mmHg; HR 75 bpm; O2 sat. 97% | Normal | Biopsy: acute cellular rejection (A1−2) and inflammatory bronchiolitis (B1R) | No | Methylprednisolone (16 mg); tacrolimus (3 mg; 15.6 ng/mL); MM (3000 mg; 3.1 µg/mL) | Chest X-ray; assessment of transplant status | Hepatic and splenic flexure pneumatosis and pneumoperitoneum | Pneumatosis resolved at time of CT scan | Indication AP CT scan; no IC; expectant management, no Qx; 1591 days |

| 10 Outpatient | 47, M | Pulmonary fibrosis, double-lung Tx | Tracheostomy; prolonged IMV; right phrenic nerve paralysis | 149 | No pain; physical examination normal | BP 115/77 mmHg; HR 73 bpm; O2 sat. 96%; Temp. 36.6 °C | Normal | No | No | Prednisone (10 mg); tacrolimus (4 mg; 11.1 ng/mL); MM (2000 mg; 1.1 µg/mL) | Chest CT scan; functional respiratory impairment | Pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum | Ascending colon and hepatic flexure | Indication AP CT scan; no IC; expectant management, no Qx; 368 days |

| 11 Inpatient | 63, M | UIP type pulmonary fibrosis; double-lung Tx | Haemothorax; post-surgical ECMO; tracheostomy; heart failure | 68 | No pain; physical examination normal | BP 125/82 mmHg; HR 91 bpm; O2 sat. 95%; Temp. 36.1 °C | PCR 17 mg/L | No | No | Methylprednisolone (8 mg); tacrolimus (4 mg; 10.6 ng/mL); MM (500 mg; 0.7 µg/mL infratherapeutic) | Chest CT scan; recurrent pleural effusion with signs of organisation | Pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum | Ascending and transverse colon | Indication AP CT scan; no HF; expectant management, no Qx; 73 days |

| 12 Inpatient | 63, F | UIP type pulmonary fibrosis; double-lung Tx | Gastroparesis | 27 | Nausea, diarrhoea, gastroparesis, bloated abdomen, discomfort on deep epigastric palpation | BP 125/81 mmHg; HR 80 bpm; O2 sat. 94%; Temp. 36.1 °C | Normal | Biopsy: no signs of acute cellular rejection (A0) and inflammatory bronchiolitis (B1R) | Gastroparesis, one vomiting and diarrhoea | Methylprednisolone (40 mg); tacrolimus (16 mg; 17.4 ng/mL, supratherapeutic); MM (2000 mg; 1.9 µg/mL) | Chest CT scan; assess sternal suture | Pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum | Terminal ileum, caecum, ascending and transverse colon | Indication AP CT scan; IC to DGM; domperidone Tt., no Qx; / |

| 13 Inpatient | 66, M | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; left single-lung Tx | No | 20 | No pain; physical examination normal | BP 145/72 mmHg; HR 83 bpm; O2 sat. 99%; Temp. 36.4 °C | Normal | Clinical | No | Methylprednisolone (20 mg); tacrolimus (6.5 mg; 8.9 ng/mL, infratherapeutic); MM (3000 mg; 4.2 µg/mL) | Chest CT scan; rule out thoracotomy dehiscence | Pneumatosis intestinalis ascending colon, hepatic flexure and transverse and pneumoperitoneum | / | No CT scan, no IC; expectant management, no Qx; 72 days |

| 14 Inpatient | 24, F | Cystic fibrosis; double-lung Tx | Wound infection | 58 | Right flank pain, diarrhoea; guarding on examination right flank, no peritoneal irritation | BP 88/51 mmHg; HR 112 bpm; O2 sat. 100%; Temp. 37 °C; | Leukocytosis (21.30 × 103/µL) with neutrophilia (19.52 × 103/µL); CRP 381 mg/L; procalcitonin 18.32 ng/L; lactate 1.8 mmol/L; HCO3− 21.5 mmol/L; pH 7.39 | Clinical | C. difficile pancolitis | Prednisone (30 mg); tacrolimus (5 mg; 6.6 ng/mL, infratherapeutic); MM (3000 mg; 1.6 µg/mL) | Abdomino-pelvic CT scan; Clinical and analytical deterioration in a patient with AGE | Pneumatosis intestinalis, portal pneumatosis, free fluid, wall thickening colon: C. difficile pancolitis | Caecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure and transverse colon | IC to GS; antibiotic Tmt. with fidaxomicin, no Qx. Dx C. difficile pancolitis; 3 days |

| 15 Inpatient | 63, M | Emphysema type COPD; right single-lung Tx | Lithium poisoning | 74 | No pain, abdominal discomfort with ingestion; physical examination normal | BP 115/82 mmHg; HR 103 bpm; O2 sat. 99%; Temp. 35.4 °C | Normal | Clinical | No | Methylprednisolone (40 mg); tacrolimus (4 mg; 17.4 ng/mL, supratherapeutic); MM (540 mg; 7.6 µg/mL, supratherapeutic) | Chest CT scan; assessment of transplant status | Pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum | Caecum, ascending colon | Indication AP CT scan; IC to DGM and GS; expectant management, no Qx; 384 days |

| 16 Inpatient | 62, M | Emphysema-type COPD; double-lung Tx | Air leak; thoracotomy and sternotomy surgical dehiscence | 9 | Subcutaneous emphysema | BP 126/60 mmHg; HR 86 bpm; O2 sat. 95%; Temp. 37 °C | Leukocytosis (15 × 103/µL) with neutrophilia (12.77 × 103/µL); CRP 27.5 mg/L | No | No | Methylprednisolone (60 mg); tacrolimus (6 mg; 12.1 ng/mL); MM (1000 mg; 7.5 µg/mL, supratherapeutic) | Chest CT scan; assessment of transplant status | Gastric pneumatosis and pneumoperitoneum. Bilateral pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema | / | No CT scan; IC to DGM; surgical Trt. for air leak and surgical dehiscence; 22 days |

| 17 Inpatient | 63, M | Emphysema-type COPD; double-lung Tx | No | 14 | No pain; physical examination normal | BP 122/85 mmHg; HR 88 bpm; O2 sat. 100%; Temp. 36 °C | Leukocytosis (13 × 103 µ/L) with neutrophilia (11 × 103 µ/L); CRP 7.6 mg/L | No | No | Methylprednisolone (50 mg); tacrolimus (10 mg; 11.1 ng/mL); MM (3000 mg; 2.7 µg/mL, supratherapeutic) | Chest CT scan; assessment of transplant status | Pneumatosis intestinalis ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse, splenic flexure and descending and pneumoperitoneum | / | No CT scan; IC to DGM; expectant management, no Qx; / |

AP CT: abdomino-pelvic CT scan; ASD: atrial septal defect; BP: blood pressure; CMV: cytomegalovirus; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; DGM: digestive medicine; Dx: diagnosis; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; F: female; FBS: fibrobronchoscopy; GI: gastrointestinal; GS: general surgery; HCO3−: bicarbonate; HR: heart rate; IC: interconsultation; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; M: male; MM: mycophenolate mofetil; NIVM: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; O2 sat.: oxygen saturation; PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PI: pneumatosis intestinalis; PHT: pulmonary hypertension; PTN: parenteral nutrition; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism; Qx: surgery; Rx: X-ray; Temp.: temperature; Tmt: treatment; Tx: transplantation; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; VSD: ventricular septal defect.

Signs of rejection: defined as the occurrence of any clinical or pathological event that resulted in the application of high-dose steroid boluses. Pathological classification of pulmonary rejection of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT).17

The mean time from transplantation to diagnosis was 198 days and the median was 68 days, ranging from 9 to 1270 days. When pneumatosis was diagnosed, 16 patients (94%) were asymptomatic or had mild abdominal discomfort (n = 2), bloating (n = 3), nausea/vomiting (n = 2) or diarrhoea (n = 1). In this group, the physical examination was normal. Only 6 patients had leukocytosis with neutrophilia and elevated CRP (Table 1). The symptomatic patient (no. 14 in Table 1) was diagnosed with Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) colitis.

At the time of the episode, 8 patients had clinical or pathological signs of rejection (47%) and 4 had signs of pulmonary (n = 2) or gastrointestinal (n = 2) infection. Eleven patients were inpatients (65%) and 6 were outpatients. All patients were on immunosuppressive treatment (corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors and antiproliferative agents).

In 76% of the cases (n = 13) pneumatosis was identified on the chest X-ray or CT scan, whose most frequent indication was to assess lung transplantation status (Fig. 2). The remaining cases were diagnosed by an abdomino-pelvic CT scan. Pneumatosis was most frequently observed in the ascending colon, hepatic flexure and transverse colon. The pneumatosis involved the caecum (n = 5), ascending colon (n = 10), hepatic flexure (n = 10), transverse colon (n = 7), splenic flexure (n = 3), descending colon (n = 2), sigmoid colon (n = 1), rectum (n = 1), terminal ileum (n = 1) and gastric fundus (n = 1). However, only 10 patients (59%) had an abdomino-pelvic CT scan to assess the distribution of pneumatosis throughout the bowel (Table 1). The patient with gastric pneumatosis (no. 16) also had a bilateral pneumothorax, multiple small breaks in continuity in the chest wall, both in the thoracotomy and sternotomy sutures, subcutaneous emphysema, and was diagnosed with air leak with thoracotomy dehiscence as a post-surgical complication.

58-year-old male with incidental finding of pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum under study for evaluation of lung transplantation (patient no. 8). Coronal reconstructions A and B) and transverse sections C and D) in lung window A and C) and soft tissue window B and D) of thoracic CT scan without intravenous contrast. A and B) Lung grafts without significant alterations. C and D) Extensive pneumatosis intestinalis is observed in the hepatic and splenic flexures of the colon (arrows), with localised air bubbles in the submucosa and serosa of the colon walls dissecting mesenteric fatty planes and delimiting the posterior aspect of the parietal peritoneum in the left hypochondrium (arrowheads). The study was completed with a contrast-enhanced abdomino-pelvic CT scan shown in Fig. 4.

The findings associated with pneumatosis observed were pneumoperitoneum in 12 patients (70%), free fluid in 2 cases (12%) and portal venous pneumatosis in 1 case (6%). No mesenteric venous pneumatosis or pneumobilia was identified in any case. One of the patients with free fluid (no. 14) was diagnosed with Clostridium colitis. Finally, 10 interconsultations were made to the Digestive Medicine (n = 6) and Digestive Surgery (n = 4) departments for the evaluation of 9 patients, 8 of whom were asymptomatic. Forty-six per cent (46%) of the patients diagnosed by chest radiography or CT scan (6/13) had an abdomino-pelvic CT scan to complete the study. Treatment was expectant management in all the cases of asymptomatic pneumatosis intestinalis. The patient with colitis (no. 14) was treated with antibiotics and the patient with gastric pneumatosis and air leak (no. 16) underwent surgery.

The mean time to resolution was 389 days (median 145 days, range 72–1591 days).

DiscussionThe incidence of post-lung transplantation pneumatosis intestinalis in our hospital was 3.1%, occurring between 9 and 1270 days post-transplantation. Patients were asymptomatic or with mild symptoms, with no major laboratory abnormalities. The radiological appearance was cystic/expansive. Treatment was conservative in all asymptomatic cases.

Of the 55 published cases of pneumatosis intestinalis in lung transplant patients, 15 were clinical cases2–12 and 40 in series of 7,13 1014 and 2315 patients. The incidence published by Thompson et al. (2%),13 Chandola et al. (2.68%)14 and Christiansen et al. (5.2%)15 is similar to our own. Since it is often an incidental finding, the true incidence is probably being underestimated. The time from transplantation to onset in the series of Thompson et al. (median 105 days, range 18–453 days),13 Chandola et al. (median 82 days, range 5–2495 days)14 and Christiansen et al. (median 47 days, range 5–1477 days)15 is similar to our own (median 68 days, range 9–1270 days). Although this is a complication that may occur over a long period of time, it is eminently late, usually appearing 6 months after the transplantation. As in the previous series,13–15 most patients were asymptomatic or had mild abdominal symptoms, with no major abnormalities on physical examination or in the laboratory tests. Patients who were truly symptomatic or had other associated disorders had alternative diagnoses to benign pneumatosis intestinalis.

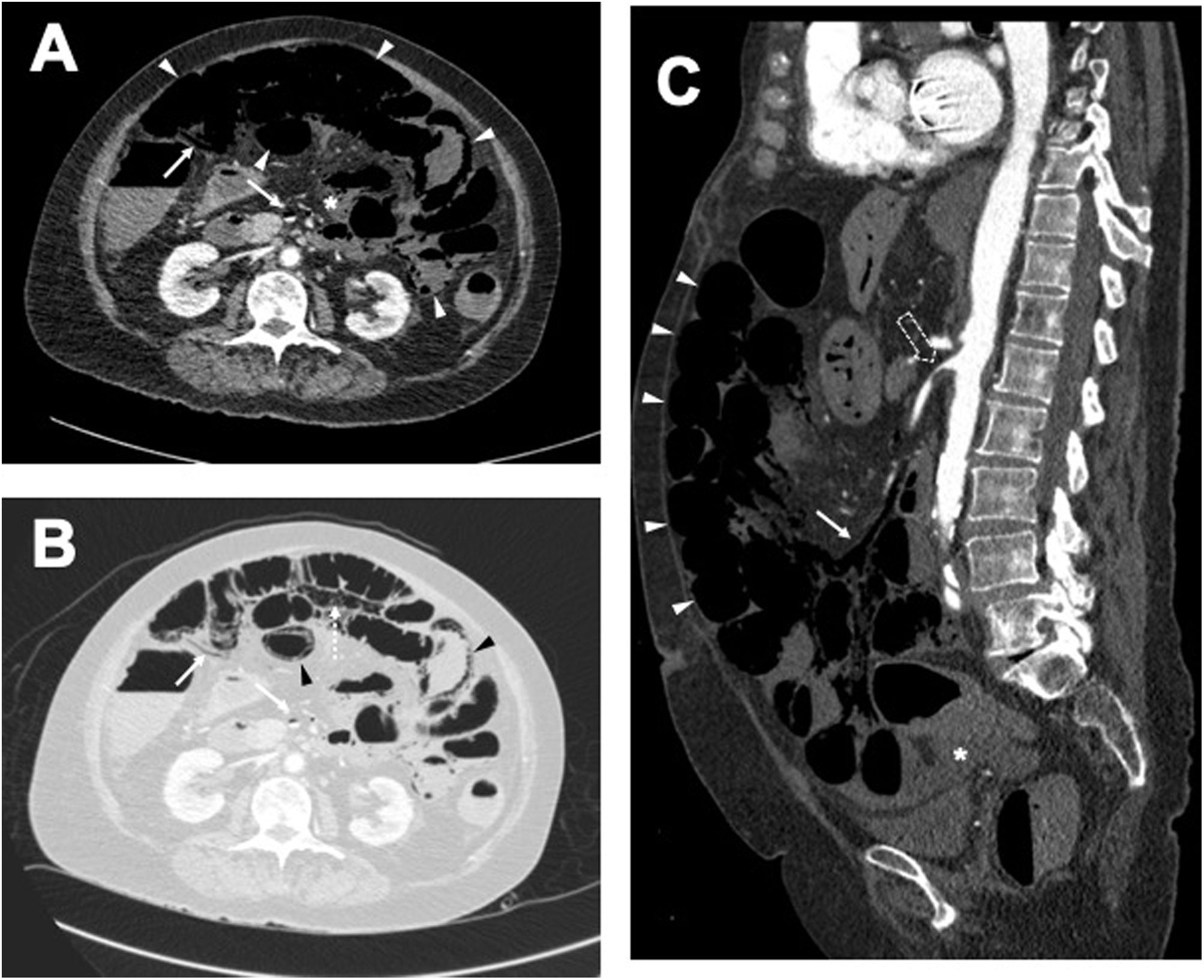

Benign pneumatosis intestinalis in transplantees often has a cystic and expansive appearance (Fig. 3), with a large amount of air in the intestinal wall. It is useful to evaluate it with the lung window to ascertain the extent (Fig. 4). In contrast, pneumatosis intestinalis due to intestinal ischaemia or occlusion predominantly affects the small bowel, and the gas bubbles usually present a finer and more linear arrangement in the wall15 and are accompanied by other warning signs such as wall thickening or thinning, absence of mural enhancement, dilatation of the intestinal loops, free fluid and inflammatory changes in the adjacent mesentery (Fig. 5). This expansive aspect of pneumatosis and the absence of other radiological findings support a benign aetiology and clinical course.15

63-year-old woman with double-lung transplant for UIP-type fibrosis (patient no. 12). Abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast performed after an incidental finding of colonic pneumatosis and pneumoperitoneum on thoracic CT scan performed to assess the sternal suture. Transverse sections in soft tissue window A) and lung B) and coronal reconstructions with soft tissue window C) and lung D). Cystic pneumatosis intestinalis in the caecum, ascending and transverse colon, with expansive appearance and a large amount of air (arrows). Abundant pneumoperitoneum both right subdiaphragmatic and in the form of large bubbles dissecting the mesenteric fat (asterisks).

Same patient as in Fig. 2. 58-year-old male with an incidental finding of pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum after lung transplantation (patient no. 8). A) Computed tomography topogram showing extensive pneumatosis intestinalis (arrowheads). Coronal reconstruction of computed tomography with intravenous contrast in soft tissue window B) and lung window C). B) The soft tissue window permits the evaluation of radiological findings associated with ectopic air, such as assessing correct uptake of the loops (arrow) and the absence of intra-abdominal free fluid. C) The lung window makes it possible to locate and assess the extent of both the pneumatosis intestinalis, extending in this case along the entire colic frame from the caecum to the sigma (arrowheads), and the pneumoperitoneum, which has a cystic and expansive appearance, dissecting mesenteric fatty planes (asterisk).

Example of pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum due to acute mesenteric ischaemia. Cross-sectional images of venous phase intravenous contrast-enhanced computed tomography with soft tissue window A) and lung window B); and sagittal reconstruction of study performed in arterial phase C). A) Dilated, thin-walled, non-enhanced small bowel loops (white arrowheads in A and C), with free fluid (asterisk in A and C) and associated mesenteric venous pneumatosis (arrows in A–C). B) Pneumatosis intestinalis (black arrowheads) and pneumoperitoneum (dashed arrow). C) Critical stenosis of the superior mesenteric artery at its origin (hollow arrow).

In our series, pneumatosis intestinalis was associated with pneumoperitoneum, portomesenteric gas and free fluid. Seventy percent of the patients in our series had associated pneumoperitoneum dissecting mesenteric fatty planes. Only one of these patients underwent surgery for an air leak with dehiscence of the sternothoracotomy (no. 16). Portal venous gas has been linked to an increased risk of requiring surgery.13 In our series, the only diagnosed case of C. difficile pancolitis was associated with free fluid and colon wall thickening.

The pathophysiology of pneumatosis intestinalis in transplant recipients remains unclear. Three causal mechanisms have been proposed: mechanical, bacteriological and biochemical.16 The mechanical theory16 suggests that gas dissects into the intestinal wall from the intestinal lumen or the mediastinum due to increased intraluminal or mediastinal pressure, as occurs in mechanically ventilated patients15 with asthma or COPD. In our series, there were no patients on mechanical ventilation during the episode. On the other hand, gas-producing bacteria enter the submucosa through defects in the mucosa and produce gas in the intestinal wall.16 Some publications have attributed pneumatosis intestinalis to CMV9,10 or C. difficile11 infections, which are common in the context of immunosuppression and are inevitably associated with transplantation. In our series, no patient presented active CMV infection and only one patient presented Clostridium colitis, whose clinical-radiological appearance was different from the asymptomatic cases. The biochemical theory16 postulates that excessive fermentation of carbohydrates in the intestinal lumen by bacteria produces gas, which is absorbed by the intestinal wall. The cystic presentation of pneumatosis in transplant patients is not conducive to this being the causative mechanism.

The association of pneumatosis with atrophy of lymphoid tissues in the intestinal wall due to immunosuppression related to the intake of immunosuppressants and corticosteroids in transplant recipients has been described.15 This atrophy compromises mucosal integrity and allows gas to enter the intestinal wall. The use of immunosuppressants and corticosteroids is an antecedent that is present in all patients in the published series13–15 and in our own, hence it would be reasonable for it to have a relevant role in the pathophysiology of post-transplant pneumatosis, probably propitiating the mechanism described by the mechanical theory. Christiansen et al.15 relate the development of pneumatosis to the placement of gastrojejunostomy tubes. In our series, post-transplantation nutrition was mainly oral, or parenteral when the latter was not possible; only one case (no. 6) had a gastrostomy at the time of the diagnosis of pneumatosis.

Although further complementary tests and consultations are often requested, the therapeutic decision was conservative in all cases. There are cases described in the literature5,13,15 of exploratory laparotomies due to radiological findings, despite the absence of symptoms and a normal physical examination and blood tests. In the series of Christiansen et al.,15 these patients are treated with supplemental oxygen, bowel rest and antibiotics, without altering the immunosuppressive regimen. In the majority of cases in our hospital, a watchful waiting attitude was maintained, without any therapeutic modification, and only in two cases was domperidone prescribed as a prokinetic (numbers 2 and 12), with a good clinical evolution in all cases and an average time to resolution of 389 days. Medical treatment should be symptomatic, and the addition of antimicrobial treatment is debatable in the absence of infectious symptoms. Finally, verifying resolution does not seem to be necessary, since it may take time to disappear or it may present a relapsing-remitting evolution,5 in most cases following a benign clinical course with conservative management.

Some of this study’s limitations are that it is a retrospective series, with the possibility of unrecorded or undetected cases or with an alternative, unidentified origin of the pneumatosis. Future prospective studies would permit a more precise determination of the incidence and time to onset and resolution of this entity.

ConclusionsPneumatosis intestinalis in lung transplant recipients is a rare complication of uncertain origin that can occur over a long period of time after transplantation. It has a characteristic radiological presentation of cystic/expansive appearance, which may or may not be associated with pneumoperitoneum and, in the absence of symptoms or other associated alterations, is of scant clinical relevance and can be managed without further diagnostic or therapeutic interventions.

Authorship/collaborators- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: Vicente Belloch Ripollés, Carlos Francisco Muñoz Núñez, Luis Martí-Bonmatí.

- 2.

Study conception: Vicente Belloch Ripollés, Carlos Francisco Muñoz Núñez.

- 3.

Study design: Vicente Belloch Ripollés, Carlos Francisco Muñoz Núñez.

- 4.

Data collection: Vicente Belloch Ripollés, Alilis Fontana Bellorín, Ali Boukhoubza, María Parra Hernández.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: Vicente Belloch Ripollés, Carlos Francisco Muñoz Núñez, Alilis Fontana Bellorín.

- 6.

Statistical processing: Vicente Belloch Ripollés.

- 7.

Bibliographic search: Vicente Belloch Ripollés, Ali Boukhoubza, María Parra Hernández.

- 8.

Editorial staff: Vicente Belloch Ripollés, Luis Martí-Bonmatí.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: Carlos Francisco Muñoz Núñez, Alilis Fontana Bellorín, Adela Batista Doménech, Luis Martí-Bonmatí.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: Vicente Belloch Ripollés, Carlos Francisco Muñoz Núñez, Alilis Fontana Bellorín, Adela Batista Doménech, Ali Boukhoubza; María Parra Hernández, Luis Martí-Bonmatí.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.