To evaluate the behavior of adrenal adenomas and metastases with dual-energy CT, analyzing the attenuation coefficient in monochromatic images at three different levels of energy (45, 70, and 140 keV) and the tissue concentrations of fat, water, and iodine in material density maps, with the aim of establishing optimal cutoffs for differentiating between these lesions and comparing our results against published evidence.

Materials and methodsThis retrospective case-control study included oncologic patients diagnosed with adrenal metastases in the 6–12 months prior to the study who were followed up in our hospital between January and June 2020. For each case (patient with metastases) included in the study, we selected a control (patient with an adrenal adenoma) with a nodule of similar size. All patients were studied with a rapid-kilovoltage-switching dual-energy CT scanner, using a biphasic acquisition protocol. We analyzed the concentration of iodine in paired water−iodine images, the concentration of fat in the paired water–fat images, and the concentration of water in the paired iodine–water and fat–water images, in both the arterial and portal phases. We also analyzed the attenuation coefficient in monochromatic images (at 55, 70, and 140 keV) in the arterial and portal phases.

ResultsIn the monochromatic images, in both the arterial and portal phases, the attenuation coefficient at all energy levels was significantly higher in the group of patients with metastases than in the group of patients with adenomas. This enabled us to calculate the optimal cutoffs for classifying lesions as adenomas or metastases, except for the arterial phase at 55 KeV, where the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for the estimated threshold (0.68) was not considered accurate enough to classify the lesions. For the arterial phase at 70 keV, the AUC was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.663‒0.899); the optimal cutoff (42.4 HU) yielded 92% sensitivity and 60% specificity. For the arterial phase at 140 keV, the AUC was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.894‒0.999); the optimal cutoff (18.9 HU) yielded 88% sensitivity and 94% specificity). For the portal phase at 55 keV, the AUC was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.663‒0.899); the optimal cutoff (95.4 HU) yielded 68% sensitivity and 84% specificity. For the portal phase at 70 keV, the AUC was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.757‒0.955); the optimal cutoff (58.4 HU) yielded 80% sensitivity and 84% specificity. For the portal phase at 140 keV, the AUC was 0.9 (95% CI: 0.834‒0.987); the optimal cutoff (16.35 HU) yielded 96% sensitivity and 84% specificity. In the material density maps, in the arterial phase, significant differences were found only for the iodine–water pair, where the concentration of water was higher in the group with metastases (1018.8 ± 7.6 mg/cm3 vs. 998.6 ± 8.0 mg/cm3 for the group with adenomas, p < 0.001). The AUC was 0.97 (95% CI: 0.893‒0.999); the optimal cutoff (1012.5 mg/cm3) yielded 88% sensitivity and 96% specificity. The iodine–water pair was also significantly higher in metastases (1019.7 ± 12.1 mg/cm3 vs. 998.5 ± 9.1 mg/cm3 in adenomas, p < 0.001). The AUC was 0.926 (95% CI: 0.807‒0.977); the optimal cutoff (1009.5 mg/cm3) yielded 92% sensitivity and 92% specificity. Although significant results were also observed for the fat–water pair in the portal phase, the AUC was insufficient to enable a sufficiently accurate cutoff for classifying the lesions. No significant differences were found in the fat–water maps or iodine–water maps in the arterial or portal phase or in the water–fat map in the arterial phase.

ConclusionsMonochromatic images show differences between the behavior of adrenal adenomas and metastases in oncologic patients studied with intravenous-contrast-enhanced CT, where the group of metastases had higher attenuation than the group of adenomas in both the arterial and portal phases; this pattern is in line with the evidence published for adenomas. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, no other publications report cutoffs for this kind of differentiation in contrast-enhanced monochromatic images obtained in rapid-kilovoltage-switching dual-energy CT scanners, and this is the first new contribution of our study. Regarding the material density maps, our results suggest that the water–iodine pair is a good tool for differentiating between adrenal adenomas and metastases, in both the arterial and portal phases. We propose cutoffs for differentiating these lesions, although to our knowledge no cutoffs have been proposed for portal-phase contrast-enhanced images obtained with rapid-kilovoltage-switching dual-energy CT scanners.

Evaluar el comportamiento de los adenomas y las metástasis suprarrenales mediante TC con energía espectral, analizando en el coeficiente de atenuación en imágenes monocromáticas a tres niveles energéticos diferentes (45, 70 y 140 KeV), y la concentración tisular de grasa, agua y iodo obtenidos en los mapas de descomposición de materiales, con el fin de establecer puntos de corte óptimos que permitan diferenciarlos, y comparar nuestros resultados con la evidencia publicada.

Materiales y métodosSe diseñó un estudio retrospectivo de casos y controles que incluyó pacientes oncológicos con diagnóstico de metástasis suprarrenal en los 6–12 meses anteriores al estudio y con seguimiento en el Hospital entre enero y junio de 2020. Por cada caso (paciente con metástasis) incluido en el estudio se seleccionó un control (paciente con adenoma suprarrenal) con un nódulo de tamaño similar. Todos los pacientes fueron estudiados con un equipo de TC con intercambio rápido de Kilovoltaje, con protocolo de adquisición bifásico. Se analizó la concentración de iodo en el par iodo-agua; la de grasa en el par grasa-agua y la de agua en los pares agua-iodo y agua-grasa, tanto en fases arterial como portal. También se analizó el coeficiente de atenuación en imágenes monocromáticas (a 55, 70 y 140 KeV) en fase arterial y portal.

ResultadosEn las imágenes monocromáticas, el coeficiente de atenuación fue significativamente mayor en el grupo de las metástasis que en el grupo de los adenomas en todos los niveles energéticos, tanto en fase arterial como en fase portal. Esto permitió calcular el punto de corte óptimo para clasificar las lesiones como metástasis o adenomas, menos para la fase arterial a 55 KeV, donde el área bajo la curva (ABC) para el umbral estimado fue 0,68 y no fue considerado un buen criterio para clasificar las lesiones. Para la fase arterial a 70 KeV, el ABC y su intervalo de confianza (IC 95%), el punto de corte óptimo y sus valores de sensibilidad (S) y especificidad (E) fueron de: 0,76 (0,663-0,899); 42,4 UH, 92% y 60%, respectivamente. Para 140 KeV, fueron de: 0,94 (0,894-0,999; 18,9 UH; 88%, 94%), respectivamente. Para la fase portal a 55 KeV, el ABC y su intervalo de confianza (IC 95%), el punto de corte óptimo y sus valores de S y E fueron de: 0,76 (0,663-0,899); 95,4 UH, 68%, 84%) respectivamente. A 70 KeV, los valores fueron: 0,82 (0,757-0,955); 58,4 UH; 80%, 84%, respectivamente. A 140 KeV: 0,9 (0,834-0,987);16.35 UH; 96%; 84%, respectivamente. En los mapas de descomposición de materiales, en la fase arterial únicamente se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el par agua-iodo, donde la concentración de agua fue mayor para el grupo de las metástasis que para los adenomas (1018,8 ± 7,6 mg/cm3 vs 998,6 ± 8,0 mg/cm3, p < 0,001). El ABC y su intervalo de confianza (IC 95%), el punto de corte óptimo y sus valores de S y E fueron de: 0,97 (0,893-0,999); 1012,5 mg/cm3; 88%, 96%). El par agua-iodo en fase portal también evidenció diferencias significativas, con concentraciones de agua de nuevo mayores para metástasis que para adenomas (1019,7 ± 12,1 mg/cm3 vs 998,5 ± 9,1 mg/cm3, p < 0,001). El ABC y su intervalo de confianza (IC 95%), el punto de corte óptimo y sus valores de S y E fueron de 0,926 (0,807-0,977); 1009,5 mg/cm3; 92%). En el par agua-grasa portal, a pesar de observarse resultados significativos, no se obtuvo un ABC en la curva ROC que permitiera utilizarlo como buen criterio para clasificar las lesiones. Sin embargo, no se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en los mapas grasa-agua ni iodo-agua ni en fase arterial ni portal, ni el de agua-grasa en fase arterial.

ConclusionesLas imágenes monocromáticas evidencian diferencias en el comportamiento entre adenomas y metástasis suprarrenales en pacientes oncológicos estudiados con TC con contraste intravenoso, con atenuación mayor para el grupo de metástasis que para el de adenomas, tanto en fase arterial como en fase portal, con un patrón acorde con la evidencia publicada para adenomas. Sin embargo, no tenemos conocimiento de otras publicaciones que describan umbrales de corte en este tipo de diferenciación en imágenes monocromáticas con contraste con equipos con intercambio rápido de Kilovoltaje, y esa es la primera aportación novedosa de nuestro estudio. Sobre los mapas de descomposición de materiales, nuestros resultados sugieren que el par agua-iodo es una buena herramienta para discriminar metástasis y adenomas suprarrenales tanto en fase arterial como en fase portal, y se proponen umbrales de corte, sin que tengamos otra referencia previa en la literatura de un umbral en fase portal con contraste con equipos de intercambio rápido de kilovoltaje.

Adrenal incidentalomas are seen in 5% of patients having computed tomography (CT) scans. Most are benign, with adenoma being the most common, even in cancer patients. As radiologists, we have to know how to differentiate between adenoma and metastasis, in order to minimise further tests involving additional costs, exposure to ionising radiation and stress for the patient.1–3

The American College of Radiology's diagnostic algorithm for adrenal incidentalomas2 is based on a combination of endocrine data, biopsy, imaging studies [positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)], oncology history and stability/growth of the lesion.

In MRI, the most useful technique is chemical shift imaging. Qualitatively, adenomas show a signal drop in the opposed phase. Quantitatively, the signal intensity index and the adrenal/spleen signal intensity ratio can be calculated. An index higher than 16.5% and a ratio below 0.71 are diagnostic for adenoma. Both approaches provide similar results.2–4

Conventional CT analyses the density of a lesion and its washout rate in a non-contrast phase and two post-contrast acquisitions: a portal phase at 60–90 s; and a delayed phase at 15 min. A density of less than 10 Hounsfield units (HU) in the pre-contrast phase is diagnostic of lipid-rich adenoma, although up to a third are lipid-poor, with attenuation greater than 10 HU. In these, calculation of absolute [(portal attenuation-delayed attenuation)/(portal attenuation-pre-contrast attenuation) × 100] and relative [(portal attenuation-delayed attenuation)/portal attenuation × 100] washout percentages are useful, with ratios ≥60% and ≥40% respectively diagnostic of adenoma. This has shown better results than chemical shift imaging in the characterisation of adenomas with density greater than 20 HU.2–11 An alternative parameter is the relative enhancement ratio (portal attenuation-pre-contrast attenuation/pre-contrast attenuation × 100%) which, with a threshold of 210%, differentiates lipid-poor adenomas from non-adenomas.7

Spectral energy (dual or multi-energy) CT allows differentiation of materials by their different attenuation profile at different energy levels. This, in practice, is achieved by acquiring images at two energy levels. There are different technological approaches, depending on the X-ray source or the detector. By source type, there are machines with: double tube (DT; two orthogonal sources working at different voltages, each with its own detector); fast kilovoltage-switching (FKVS; one tube rapidly alternates between high and low kilovoltage at each rotation); "dual spin" (two consecutive acquisitions at each rotation at a different voltage); and "split-filter" (the beam passes through a gold and tin filter, and is separated on the "z" axis into two different beams). For the detector, there are machines commercially available with dual-layer detectors (DLD), with an upper and lower layer absorbing the low and high energy photons respectively. In the near future, photon-counting, using detectors with a semiconductor material, will make it possible to detect photons with specific energies.12–14

Spectral CT provides new families of images12–14:

- □

Virtual non-contrast images (VNCI): a digital subtraction of the iodine gives it an appearance similar to a non-contrast image (NCI).

- □

Monochromatic images (MCI): simulate the appearance of those acquired with a monoenergetic source; at low energy levels contrast resolution and vascular enhancement (but also noise) increase, and at high levels metal artefact is reduced.

- □

Material decomposition maps (MDM): enable the tissue concentration of a material to be assessed using a material pair approach or multi-material decomposition algorithms (three or more materials), assuming that only the pre-selected materials with known composition exist in a voxel, and their proportion is estimated based on their attenuation profile at two energy levels. This allows the creation of maps which selectively display the material of interest according to diagnostic needs. The most commonly used is iodine–water.

VNCI were widely studied for the assessment of adenomas because of their potential to bypass the non-contrast phase and reduce the radiation dose to the patient.15–18 Although a bit lower, comparable sensitivity (S) values have been reported when comparing NCI and VNCI for the diagnosis of adenoma.3,15 A meta-analysis by Conolly et al.1 describes a similar S between NCI (57%) and VNCI (54%), although rates have been reported in the range of 50%–71%.19,20

The tendency for VNCI to overestimate attenuation is well known, regardless of the manufacturer.1,21–23 Botsikas et al.24 found statistically significant differences in attenuation between VNCI obtained from the portal phase and NCI, with a mean difference of 4.02 HU. This could lead to a lesion being falsely considered as indeterminate by exceeding the classic 10 HU threshold in VNCI, and is related to the phase at which the series of images from which the VNCI originate is acquired; as adenomas reach their peak enhancement at 60 s and then undergo washout, attenuation in VNCI coming from an acquisition at 60 s (or earlier) may be overestimated when compared to those obtained from later acquisitions. Thresholds of ≤22 HU have been proposed to improve S in the diagnosis of lipid-rich adenoma, but with lower specificity (Sp).21,23 Similar S has been described between NCI and VNCI for distinguishing between benign and malignant nodules, both for DT and FKVS scanners.1,17,25

However, in most oncology studies, NCI are not available and we therefore need to develop strategies to differentiate between adenomas and metastases without having to recall the patient. MCI and MDM analysis is a good alternative.

In MCI, the attenuation of a tissue depends on its composition and the energy level used, and decreases as the energy level increases.12,13 Numerous studies have evaluated the spectral attenuation curve in non-contrast and contrast-enhanced studies in the differentiation between adenomas and non-adenomas/metastases.8,15,19,24–27

There are fewer references on MDM describing the behaviour of adenomas and metastases with DT devices (analysing iodine density and fat fraction),15,25 DLD devices (analysing iodine density)8,23 and FKVS devices (analysing fat–iodine and water–iodine maps,18 fat–water without contrast,26 fat–iodine, iodine–fat, fat–water and water–fat–water28).

A pilot study conducted by our group with an FKVS scanner assessed differences between adenomas and adrenal metastases in oncology patients, studying MCI and MDM in biphasic contrast-enhanced CT. Attenuation differences in MCI and tissue concentrations of iodine–water, water–iodine, fat–water and water–fat were found between the two groups of lesions,29 and these data prompted us to conduct this study with a larger sample in order to analyse ROC curves. The aim of the study was therefore to examine the behaviour of adenomas and adrenal metastases by spectral CT, analysing the attenuation coefficient in MCI at three different energy levels (45, 70 and 140 keV), and the tissue concentration of fat, water and iodine obtained in MDM, in order to establish optimal cut-off points for differentiating between them, and to compare our results with the published evidence.

Materials and methodsThe research protocol for this observational, analytical, cross-sectional retrospective study was approved by the hospital's Research Committee.

We included oncology patients with follow-up at our centre from January 2018 to June 2020, with biphasic CT of chest, abdomen and pelvis (arterial and portal phases) acquired with standardised spectral CT protocol and previous studies supporting the diagnosis of adenoma (control) or metastasis (case) from at least the 6–12 months prior to the study and available in the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). Patients were excluded if their raw data (which would allow post-processing) could not be accessed in PACS, or if they had with adrenal hyperplasia, understood as unilateral or bilateral enlargement (>10 mm in thickness), with nodular shape or uniform margins, but normal morphology. All patients included signed the informed consent form giving their permission for the use of their clinical data in research studies before the test was performed.

The standard reference for the diagnosis of adenoma was the diagnostic criteria described above for contrast CT, MRI and PET-CT and stability over the time each patient was being followed up. For metastases, the diagnosis was made on detection of a new adrenal lesion and/or growth of an adrenal lesion on CT or MRI, or increased cellular activity on PET-CT. Histopathological confirmation was not obtained in any of the cases.

For each metastasis included in the study, we selected an adenoma of similar size, as described in the "Results" section. All patients were studied with an FKVS CT scanner (Revolution CT; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). Iodinated contrast (Iopamiro 300 mg/ml solution for injection, Bracco Imaging S.P.A) was used and a volume of 90 cc was administered at a flow rate of 4 cc/s. The arterial phase was acquired by monitoring the arrival of contrast in the descending thoracic aorta (at the level of the carina). A region of interest (ROI) was placed at this location and arterial acquisition began 15 s after the threshold of 100 HU was exceeded. The portal phase is acquired 35 s after the end of the arterial phase. The spectral image acquisition protocol was: helical acquisition; rotation time: 0.6 s; detector coverage: 80 mm; pitch: 0.992:1; coverage speed: 132.29 mm/s; FOV: 38.5 cm; 195 mA; noise index 20.0; slice thickness: 1.25 mm; interval 0.8 mm; ASIR-V: 50%.

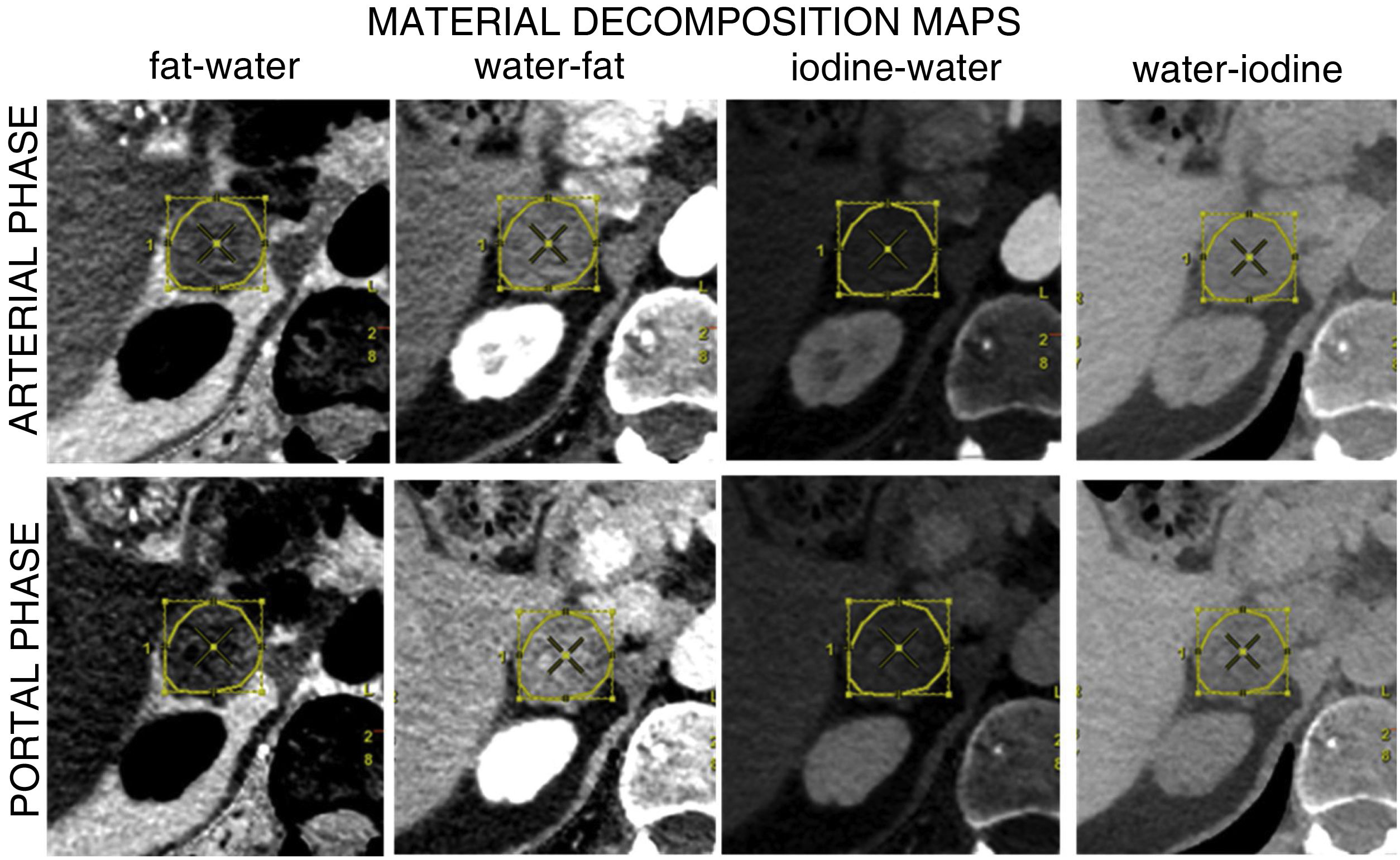

CT scans and medical history were reviewed to obtain the study variables: primary tumour, type of lesion (adenoma/metastasis), side of the body (right/left), attenuation coefficient in MCI (at 55, 70 and 140 keV) in portal and arterial phases (Fig. 1); iodine concentration in the iodine–water pair, fat concentration in the fat–water pair and water concentration in the water–iodine and water–fat pairs, all in arterial and portal phases (Fig. 2). Each nodule was assessed blind by the same radiologist with 10 years' experience in abdominal radiology. In patients with more than one nodule, a maximum of two were chosen, selecting those with the largest size or most evident nodular morphology. A program provided by the manufacturer was used to generate a loading protocol with the chosen energy levels and maps with constant centre and window width (Advantage Workstation Server 3.2 Ext 3.2, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). A freehand ROI was drawn covering 50–75% of the area of each lesion in the axial slice where its nodular morphology was most evident (avoiding artefacts, calcifications, vascular structures and necrotic/haemorrhagic areas), which was cloned and propagated to the different series of the study, with an approximate post-processing time of 15 min per nodule. All results were stored in PACS and data were collected in a decoupled database, in accordance with current legislation.

In the statistical analysis, for the description of the study population, qualitative variables are expressed as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies. All quantitative variables were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test), so mean values ± standard deviation (SD) are given.

Student's t test was applied to compare the tissue concentration of fat in the fat–water pair, iodine in the iodine–water pair, and water in the water–fat and water–iodine pairs obtained by MDM (expressed in mg/cm3) and also the attenuation coefficients (HU) in the MCI (at 55, 70 and 140 keV) between metastases and adenomas.

For parameters where differences between adenomas and metastases were evident, ROC curves were constructed and the area under the curve (AUC) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated to assess the goodness of fit for the classification of the lesion. A parameter was considered to classify the lesion acceptably when the AUC was greater than 0.7, in which case we calculated the optimal cut-off point, and S and Sp of the classification for that point.

Differences were considered as statistically significant when the p-value was less than 5%. Data analysis was performed with Stata IC, v. 14 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA).

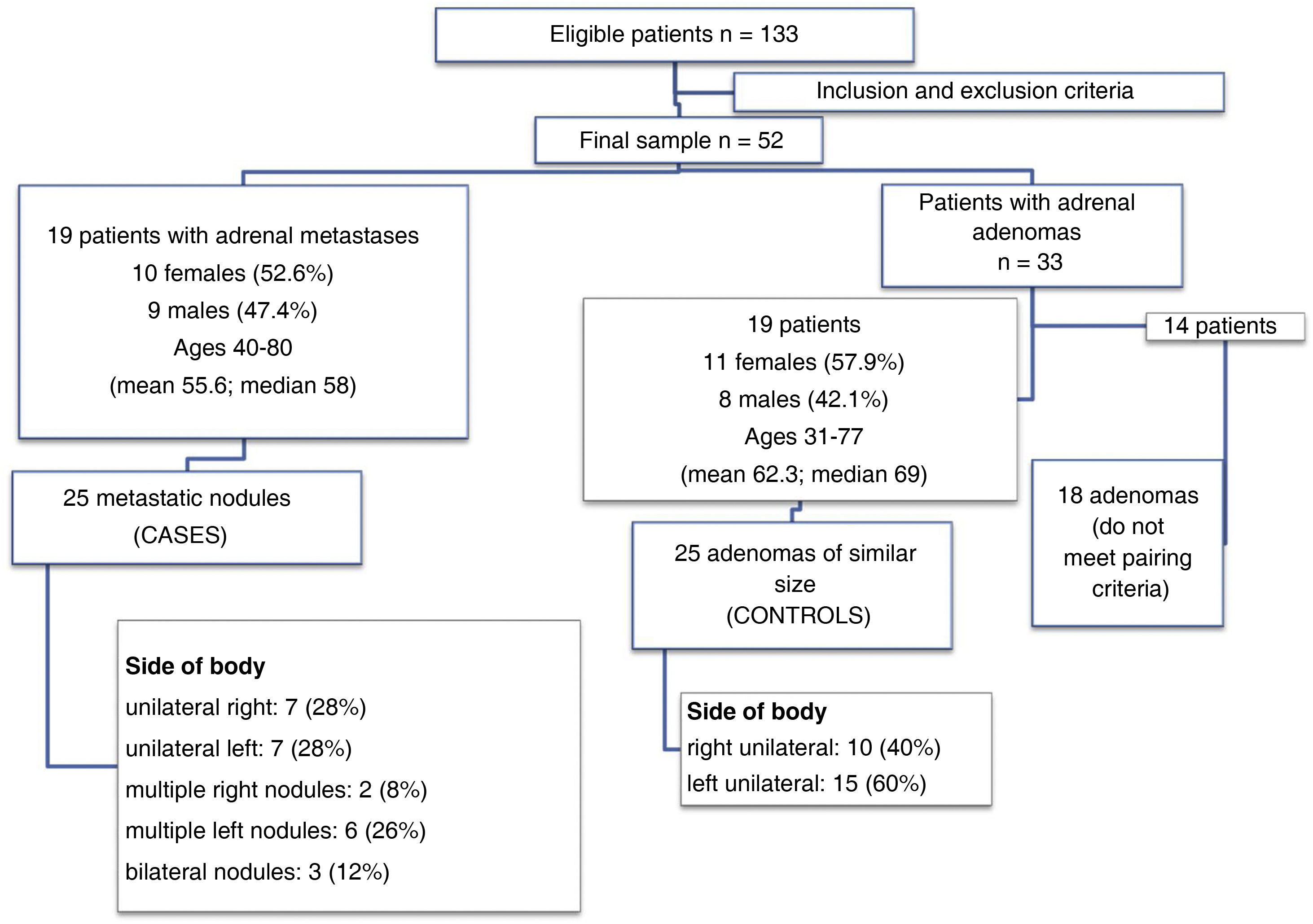

ResultsFrom January 2018 to June 2020, of the 133 eligible patients, 52 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Nineteen patients had a total of 25 metastatic nodules. The remaining 33 had a total of 43 adenomas, and we selected the 19 patients with 25 adenomas of similar size to the metastases. Fig. 3 summarises these data and describes the demographics of the sample. Table 1 shows the size of the lesions after applying the pairing criteria. The lungs were the most common location for the primary tumour in both groups of patients included in the study, and all patients had at least previous CT scans for comparison, with some also having PET-CT and/or MRI to confirm the suspected diagnosis of metastasis or adenoma (Table 2).

Size of adrenal nodules classified as adenomas or metastases.

| Adrenal adenomas (n = 25) | Adrenal metastases (n = 25) | p-Value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size in anterior–posterior axis (Median [Q1–Q3], mm) | 19 | [16–27] | 25 | [19–35] | 0.089 |

| Size in transverse axis (Median [Q1–Q3], mm) | 15 | [12–20] | 20 | [14–27] | 0.05 |

Primary tumour of the oncology patients included in the study and correlation with previous studies to support the diagnosis, either of the same imaging modality (CT) or different (PET-CT or MRI).

| Primary | Correlation with previous | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Rate | CT | MRI | PET/CT | |

| Patients with adrenal adenomas (n = 19) | Lungs | 10 (52.6%) | 10 (100%) | 0 | 4 |

| Breast | 4 (21%) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | |

| Stomach | 1 (5.2%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 1 (5.2%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Rectum and cholangiocarcinoma | 1 (5.2%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Larynx and lung | 1 (5.2%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Oesophagus | 1 (5.2%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Patients with adrenal metastases (n = 19) | Lungs | 13 (68.4%) | 10 (77%) | 1 (7.6%) | 9 (69.2%) |

| Renal | 2 (10.5%) | 2 (100%) | 0 | 1 (50%) | |

| Stomach | 2 (10.5%) | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Colon | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Breast | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

For MCI, the attenuation coefficient of metastases and adenomas at 55, 70 and 140 keV, in arterial and portal phase are shown in Table 3. In all cases, the attenuation coefficient was significantly higher in the metastasis group than in the adenoma group. Fig. 4 shows the ROC and AUC curves for all combinations, which was greater than 0.7. This allowed calculation of the optimal cut-off point for classifying lesions as metastases or as adenomas, except for the arterial phase at 55 keV, where the AUC for the calculated threshold was 0.68 and was not considered a good criterion for classifying lesions. For the arterial phase, at 70 keV, the ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.663−0.899) for an optimal cut-off point of 42.4 HU (S: 92%, Sp: 60%). At 140 keV, the ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.894−0.999) for an optimal cut-off point of 18.9 HU (S: 88%, Sp: 94 %). For the portal phase, at 55 keV, the ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.663−0.899) for a threshold of 95.4 HU (S: 68%, Sp: 84%). At 70 keV, the ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.82 (95% CI 0.757−0.955) for an optimal cut-off point of 58.4 HU (S: 80%, Sp: 84%). At 140 keV, the ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.9 (95% CI 0.834−0.987) for an optimal cut-off point of 16.35 HU (S: 96%, Sp: 84%).

Attenuation coefficients (mean ± SD, HU) in adrenal nodules classified as adenomas or metastases.

| Adrenal adenomas (n = 25) | Adrenal metastases (n = 25) | Difference* (95% CI) | p-Value** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial | |||||

| 55 keV | 68.7 ± 33.74 | 96.66 ± 36.1 | −28.0 ± 9.9 | (−47.8, −8.1) | 0.007 |

| 70 keV | 39.9 ± 21.1 | 64.7 ± 19.7 | −24.8 ± 5.8 | (−36.4, −13.2) | <0.001 |

| 140 keV | 7.7 ± 9.3 | 28.8 ± 5.9 | −21.2 ± 2.2 | (−25.6, −16.7) | <0.001 |

| Portal | |||||

| 55 keV | 73.9 ± 34.9 | 112.0 ± 35.0 | −38.1 ± 8.5 | (−55.1, −21.0) | <0.001 |

| 70 keV | 42.8 ± 16.2 | 73.9 ± 19.8 | −31.2 ± 5.1 | (−41.4, −20.9) | <0.001 |

| 140 keV | 8.2 ± 9.7 | 31.4 ± 10.4 | −23.2 ± 2.8 | (-28.9, −17.6) | <0.001 |

In MDM (Table 4), in arterial phase only statistically significant differences were found in the water–iodine pair, with higher water concentrations for metastases than for adenomas. The ROC curve revealed an AUC of 0.97 (95% CI 0.893−0.999). The optimal cut-off point for classifying the lesion as metastasis or adenoma was 1,012.5 mg/cm3 (S: 88%, Sp: 96%, Fig. 5).

Decomposition maps (mean ± SD, mg/ml) in adrenal nodules classified as adenoma or metastasis.

| Adrenal adenomas (n = 25) | Adrenal metastases (n = 25) | Difference* (95% CI) | p-Value** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial phase | |||||

| Fat–water | −1,186.3 ± 540.6 | −1318.7 ± 685.7 | 132.4 ± 174.6 | (−218.7, 483.5) | 0.452 |

| Iodine–Water | 15.3 ± 7.1 | 17.1 ± 9.0 | −1.7 ± 2.3 | (−6.4, 2.9) | 0.412 |

| Water–Fat | 2,189.8 ± 546.0 | 2343 ± 686.8 | −153.2 | (−506.1, 199.6) | 0.389 |

| Water–iodine | 998.6 ± 8.0 | 1018.8 ± 7.6 | −100.5 ± 80.1 | (−261.6, 60.6) | <0.001 |

| Portal phase | |||||

| Fat–water | −1,267.8 ± 360.1 | −1557.6 ± 676.8 | 289.7 ± 153.3 | (−18.5, 598.0) | 0.065 |

| Iodine–water | 16.5 ± 4.7 | 20.3 ± 8.9 | −3.9 ± 2.0 | (−7.9, 0.2) | 0.061 |

| Water–Fat | 2,278.4 ± 363.5 | 2592.1 ± 677.3 | −313.6 ± 153.7 | (−622.7, −4.5) | 0.047 |

| Water–iodine | 998.5 ± 9.1 | 1019.7 ± 12.1 | −101.8 ± 80.3 | (−263.2, 59.6) | <0.001 |

In the portal phase, adenomas tended to have a higher fat concentration in the fat–water pair than metastases, while metastases tended to have a higher iodine concentration in the iodine–water pair than adenomas, with non-significant results (Table 4). Statistically significant differences were found for the water–fat and water–iodine pairs, with higher water concentration for metastases than for adenomas in both pairs. For the water–fat pair, the ROC curve revealed an AUC of 0.675 and was therefore not considered a good criterion for classifying lesions. For the water–iodine pair, the ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.926 (95% CI: 0.807−0.977) and we were able to calculate an optimal cut-off point of 1,009.5 mg/cm3 to differentiate between adenomas and metastases (S: 92%; Sp: 92%, Fig. 5).

ConclusionsThe study analyses differences between adenomas and metastases using MCI and MDM, as NCI were not available in our acquisition protocol.

In the MCI, the attenuation coefficient was higher for the metastasis group than for the adenoma group at all three energy levels assessed, both in the arterial and portal phases. This confirms the findings of our pilot study29 and is a pattern in line with published evidence; Glazer et al.15 and Botsikas et al.24 describe similar behaviour in their series of adenomas. Our portal phase attenuation values at 70 keV for adenomas and metastases are very similar to those described by Martin et al. in a conventional portal phase at 120 kVp.25 However, to our knowledge there are no other publications describing cut-off thresholds in contrast MCI in this type of differentiation with FKVS, and this is the first novel contribution of our study. Imaging at 140 keV provides the highest S and Sp figures. The potential of these images for differentiation between adenomas and metastases versus VNCI or NCI is another interesting aspect, although further studies are needed to prove this. In our series there seemed to be a decrease in the attenuation coefficient in the two groups of lesions as we increased the energy level, although these results should be verified in another study with a different statistical analysis.

MCI obtained from NCI have also been studied in the differentiation between adenomas and metastases; Ju et al.26 describe significant differences in attenuation at all energy levels between 40 and 140 keV, lower for adenomas than for metastases, with the difference at 40 keV being maximal. At this level, a threshold of 21.78 HU distinguishes between the two groups (S: 92.1%, Sp: 76.6%). In addition, they found different spectral attenuation curves; at low energy levels, metastases show higher attenuation values, and progressively decrease with increasing kilovoltage, in contrast to adenomas. Similar attenuation findings were observed by Gupta et al.,19 with both using FKVS. Using a DT system, Shi et al.27 reported S of 78.6% and Sp of 100% in the differentiation of adenomas and metastases for a threshold of plus 2.42 HU difference between 80 and 140 keV and a threshold of plus 6.95 HU difference between 40 and 100 keV. Similar behaviour has also been described with DLD CT.8

However, these measurements are subject to variability, so caution should be exercised before applying results universally. Variations in attenuation have been reported between manufacturers depending on energy level and lesion type,9,13,30 and intra-individual differences in attenuation in serial controls with the same type of scanner and between different scanners, with less variability in the portal phase than in the arterial phase.31,32

In our MDM we found significant differences in water concentrations in the water–iodine (arterial and portal) and water–fat (portal) map, but the water–iodine pair provided the measurements with the highest levels of statistical significance and was the only one which allowed us to calculate thresholds with ROC curves. Reviewing the literature, Morgan et al.18 studied fat–iodine and water–iodine pairs in the diagnosis of lipid-rich adenomas with FKVS. Their spectral acquisition was only in “the pancreatic parenchymal or delayed hepatic arterial phase”, while the pre-contrast and portal phases were acquired with a conventional beam. For the water–iodine map, they described a water threshold very similar to ours, but with lower S and Sp, and they also found no significant difference between adenomas with low lipid content and other lesions with low lipid content, such as metastases. We have not found any other references to the portal water–iodine pair in the differentiation of adenomas and metastases, so the threshold of 1,009.5 mg/cm3 is the second novel contribution of our study.

Ju et al.26 assessed fat–water maps in non-contrast studies with FKVS. They found significant differences in fat concentration, higher for adenomas than for metastases. In our series, fat concentration was also higher for adenomas than for metastases in the fat–water pair, although with a non-significant p-value. We believe this is likely to be related to the contribution of iodine in MDM.

Mileto et al.28 compared fat–iodine, iodine–fat, fat–water and water–fat pairs in adenomas and metastases with FKVS and acquisitions with contrast, but with more heterogeneous spectral acquisition protocols than ours. Like us, they found higher fat concentrations in the fat–water pair in adenomas than in metastases, while in the water–fat pair they were higher for metastases than for adenomas. However, they were able to find significant differences in all pairs. Comparatively, our series had a higher water concentration, probably due to the homogeneity of the spectral acquisition protocol.

Glazer et al.15 found a good correlation between NCI and iodine–water maps in their series of adenomas with a DT system.

Martin et al.,25 with DT and pre-contrast and contrasted acquisitions, found lower iodine density values and higher fat fraction for adenomas than for metastases.

Higher portal phase iodine densities have been described for adenomas than for metastases with DLD,23 although the combination of this value with VNCI attenuation is superior to using both values separately (iodine/VNCI ratio).

However, again there is variability in the MDM measurements. On iodine quantification, systematic deviations have been described with DT systems with underestimation of iodine concentration at concentrations higher than 10 mg/ml and overestimation at 10 mg/ml or less.33 With DLD, portal phase estimates are subject to less intra-individual variability.32 In addition, the equipment is not able to detect iodine concentrations below 0.8−1 mg/cm334 and enhancement needs to be defined, as different thresholds of 0.5 mg/cm3 and 1.3–2.0 mg/cm3 respectively, have been described with DT and FKVS.13,35 In addition, differences in absolute iodine concentration in viscera, lymph nodes and vessels have been reported by age group, gender and body mass index in healthy patients.36 Moreover, the attenuation of lesions in NCI and their location affect the quantification of iodine.35 This leaves the door open for multicentre studies with large samples to standardise criteria and thresholds.

Our study has several limitations. It was a retrospective study conducted at a single centre, with a small sample size and no histological confirmation in any of our patients. There was also no division of adenomas into typical and lipid-poor subgroups for analysis when comparing to the group with metastases. The only criterion for pairing the groups was similar size, but we did not analyse the impact of other factors such as body mass index (this could be mitigated with a calculation of values normalised to the aorta35,36). Additionally, the metastasis group was made up mostly of patients with lung cancer, but the hypervascular nature of other primaries may have skewed the data.

In summary, both IMC and MDM obtained with spectral energy are useful in the differentiation between adenomas and metastases in cancer patients studied with intravenous contrast-enhanced CT. The behaviour of adenomas and metastases in MCI in our series conforms to previously published patterns, but as a novelty we propose cut-off thresholds in this type of differentiation in MCI with contrast with FKVS CT. In MDM, our results suggest that the water–iodine pair is a good tool for discriminating between adrenal metastases and adenomas in both arterial and portal phases, and we propose cut-off thresholds, having found no other previous references in the literature to a threshold in portal phase with contrast with the FKVS technique.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: RCA.

- 2.

Study conception: RCA.

- 3.

Study design: CAV and IJTV.

- 4.

Data collection: RCA, AAV and AFA.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: CAV and IJTV.

- 6.

Statistical processing: CAV and IJTV.

- 7.

Literature search: AAV, AFA and MRR.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: RCA.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: CAV, IJTV and MRR.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: VMV, CAV and IJTV.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.