To analyse the efficacy of the procedure for withdrawing an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter and the clinical and radiological factors associated with difficult withdrawal.

Material and methodsThis retrospective observational study included patients who underwent IVC filter withdrawal at a single centre between May 2015 and May 2021. We recorded demographic, clinical, procedural, and radiological variables: type of IVC filter, angle with the IVC > 15°, hook against the wall, and legs embedded in the IVC wall > 3 mm. The efficacy variables were fluoroscopy time, success of IVC filter withdrawal, and number of attempts to withdraw the filter. The safety variables were complications, surgical removal, and mortality. The main variable was difficult withdrawal, defined as more than 5 min fluoroscopy or more than 1 attempt at withdrawal.

ResultsA total of 109 patients were included; withdrawal was considered difficult in 54 (49.5%). Three radiological variables were more common in the difficult withdrawal group: hook against the wall (33.3% vs. 9.1%; p = 0.027), embedded legs (20.4% vs. 3.6%; p = 0.008), and >45 days since IVC filter placement (51.9% vs. 25.5%; p = 0.006). These variables remained significant in the subgroup of patients with OptEase IVC filters; however, in the group of patients with Celect IVC filters, only the inclination of the IVC filter >15 ° was significantly associated with difficult withdrawal (25% vs 0%; p = 0.029).

ConclusionDifficult withdrawal was associated with time from IVC placement, embedded legs, and contact between the hook and the wall. The analysis of the subgroups of patients with different types of IVC filters found that these variables remained significant in those with OptEase filters; however, in those with cone-shaped devices (Celect), the inclination of the IVC filter >15° was significantly associated with difficult withdrawal.

Analizar la eficacia del procedimiento de retirada de filtro de vena cava inferior (FVCI), así como los factores clínico-radiológicos asociados a retirada difícil.

Material y métodoEstudio retrospectivo, observacional y unicéntrico de pacientes tratados mediante retirada de FVCI entre mayo del 2015 y mayo del 2021. Se recogieron variables clínico-demográficas, del procedimiento y radiológicas: tipo de FVCI, angulación respecto a la vena cava inferior (VCI) > 15 °, gancho contra pared y patas del dispositivo incrustadas en la pared de VCI > 3 mm. Las variables de eficacia fueron: tiempo de fluoroscopia, éxito en la retirada del FVCI y número de intentos a retirada. Como variables de seguridad: presencia de complicaciones, retirada quirúrgica y mortalidad. La variable principal fue la retirada difícil, definida como más de 5 min de fluoroscopia o más de un intento de retirada.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 109 pacientes, 54 (49,5%) fueron considerados retirada difícil. Las variables radiológicas gancho contra pared (33,3% vs. 9,1%; p = 0,027), patas incrustadas (20,4% vs. 3,6%; p = 0,008) y > 45 días desde la colocación (51,9% vs. 25,5%; p = 0,006) fueron significativamente más frecuentes en el grupo retirada difícil. Estas variables mantienen la asociación al analizar los FVCI Optease®. En los FVCI Celect® solo se asoció con retirada difícil la inclinación del FVCI > 15 ° (25% vs. 0%; p = 0,029).

ConclusiónSe ha encontrado asociación entre retirada difícil y las variables: tiempo desde colocación del FVCI, patas incrustadas y contacto del gancho con pared de VCI. Al analizar según el tipo de FVCI, estas variables se mantienen en el tipo Optease®, en cambio, la variable inclinación más de 15° dificulta la retirada de los dispositivos de morfología cónica (Celect®).

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), is a common disease. The VITAE study1 estimated that more than 1.5 million cases of VTE occur annually in Europe, associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.2

Anticoagulant therapy is effective as primary treatment and in preventing recurrence in most cases of uncomplicated DVT and PTE.3 However, anticoagulant therapy can lead to major bleeding complications in 1–5% of cases.4 In this group of patients, and those for whom anticoagulation is contraindicated, the placement of temporary inferior vena cava filters (IVCF) may be indicated.3,5

With the development of retrievable IVCF, there has been an increase in their use, particularly with prophylactic and relative indications. Unfortunately, although there is strong evidence demonstrating the benefits of anticoagulation in VTE, the evidence for using IVCF remains weak.6 There are other scenarios in which placement of IVCF may be indicated, but the recommendations of the different scientific societies in these situations are inconsistent and the level of evidence is low.7 These indications include the use of filters in addition to anticoagulation in patients with: 1) recurrent thromboembolic events; 2) DVT progression; 3) massive or high-risk PTE with concomitant DVT and increased risk of death from secondary embolisation; 4) iliocaval DVT or proximal free-floating thrombus; 5) thrombolysis of an iliocaval DVT; 6) massive PTE treated with thrombectomy or thrombolysis; 7) difficulties in maintaining anticoagulation at therapeutic doses; and 8) high risk of anticoagulation-related complications.5,7

The different treatment guidelines agree on removing the filters as soon as they are no longer necessary (for example, once there is no longer any thromboembolic risk or when anticoagulation is no longer contraindicated).3,5,8 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety communication in 2014 in which it recommended removing the IVCF as soon as the risk/benefit ratio supports removal and the patient’s state of health makes the procedure feasible.9

Despite these recommendations, some series report that only a third of IVCF are retrieved.10 Use of these devices is not without complications.11 Both failed retrieval and prolonged indwelling time before retrieval have been associated with complications such as device fracture, migration or penetration into adjacent organs, increasing the risk of DVT.12

The most recent registries report a higher retrieval rate, of approximately 77%.13 The follow-up methods and retrieval techniques for these devices vary from one institution to another, sometimes involving complex procedures and requiring advanced techniques for successful removal.14 A range of variables associated with difficult removal have been studied; longer procedures and the use of supplementary or more invasive material are necessary for IVCF retrieval in these cases.15

The aim of this study was to analyse the efficacy of the IVCF retrieval procedure and the clinical-radiological factors associated with difficult removal.

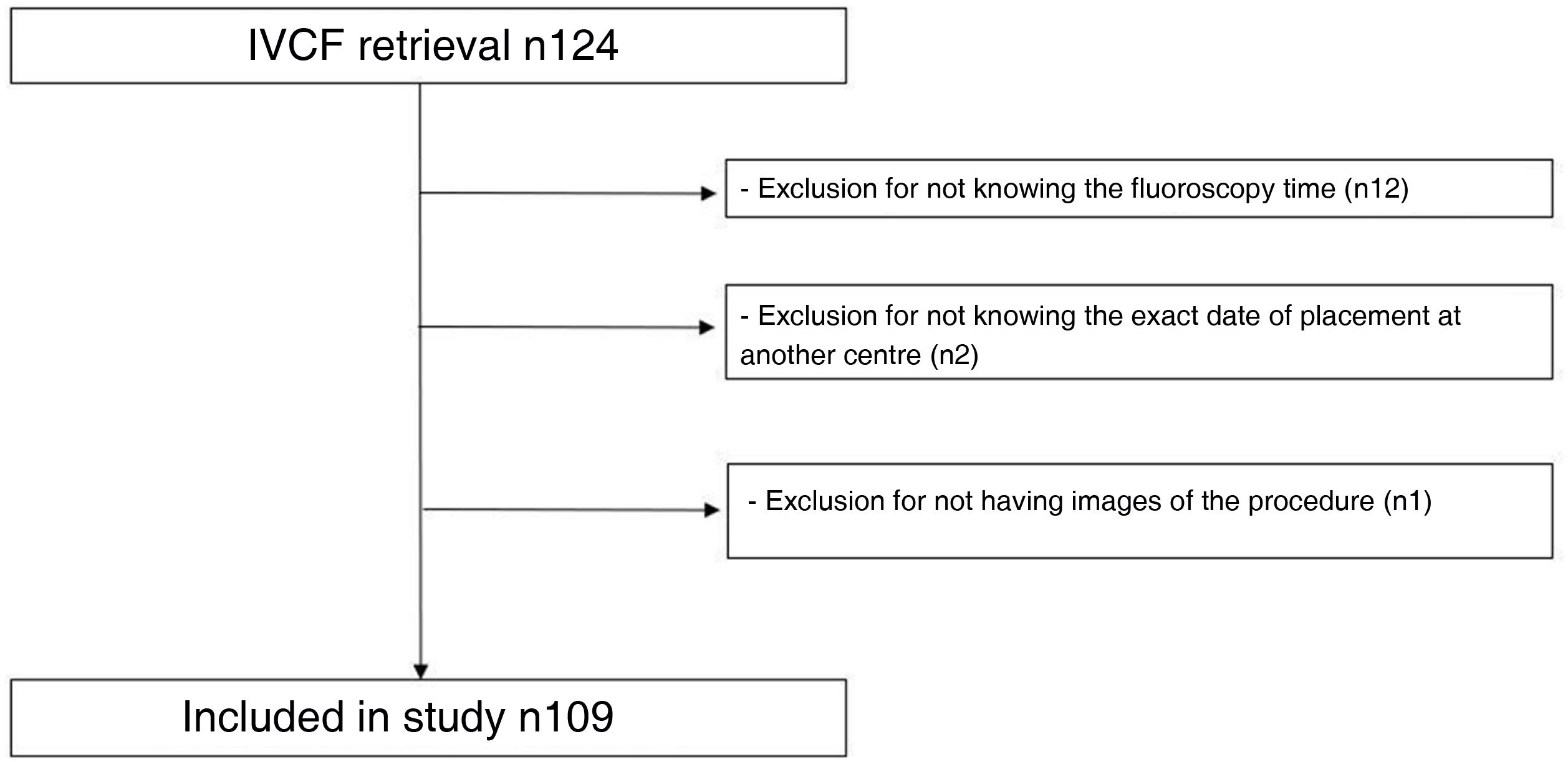

Material and methodsStudy design and inclusion criteriaA retrospective observational analysis of patients undergoing IVCF retrieval at our centre from May 2015 to May 2021 was conducted. Inclusion criteria were patients ≥18 years of age who had an IVCF removed. Patients with an unknown fluoroscopy time, or in whom the radiological variables under study could not be evaluated, were excluded.

The study protocol was approved by the local Independent Ethics Committee (registration number HCB.2021.0729), as established in laws and regulations both nationally (Law 14/2007, of 3 July, on Biomedical Research) and internationally (Declaration of Helsinki, in its last update of Fortaleza, Brazil, 2013). Given the retrospective nature of the analysis, specific informed consent was not required for the inclusion of participants. All patients gave their signed informed consent for the procedure to be performed.

Study populationWe collected demographic parameters (age, gender), along with the presence of comorbidities (congestive heart failure [CHF]), cardiovascular risk factors (arterial hypertension [HT], obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), risk factors for VTE (history of VTE, recent surgery, oncological history), the form of presentation (diagnosis of PTE or acute DVT at the time of IVCF placement) and whether or not they were on anticoagulant therapy.

The indication for IVCF placement was classified as: 1) absolute indication: in cases of acute VTE with contraindication for anticoagulation, or such therapy contraindicated by anticoagulation-related complication, or thrombus progression despite treatment; 2) relative: free-floating thrombosis in the iliocaval or IVC territory, or in cases of thrombolysis of the iliocaval region; 3) prophylactic: in cases of trauma or in the pre-surgical setting in patients at high risk of VTE.

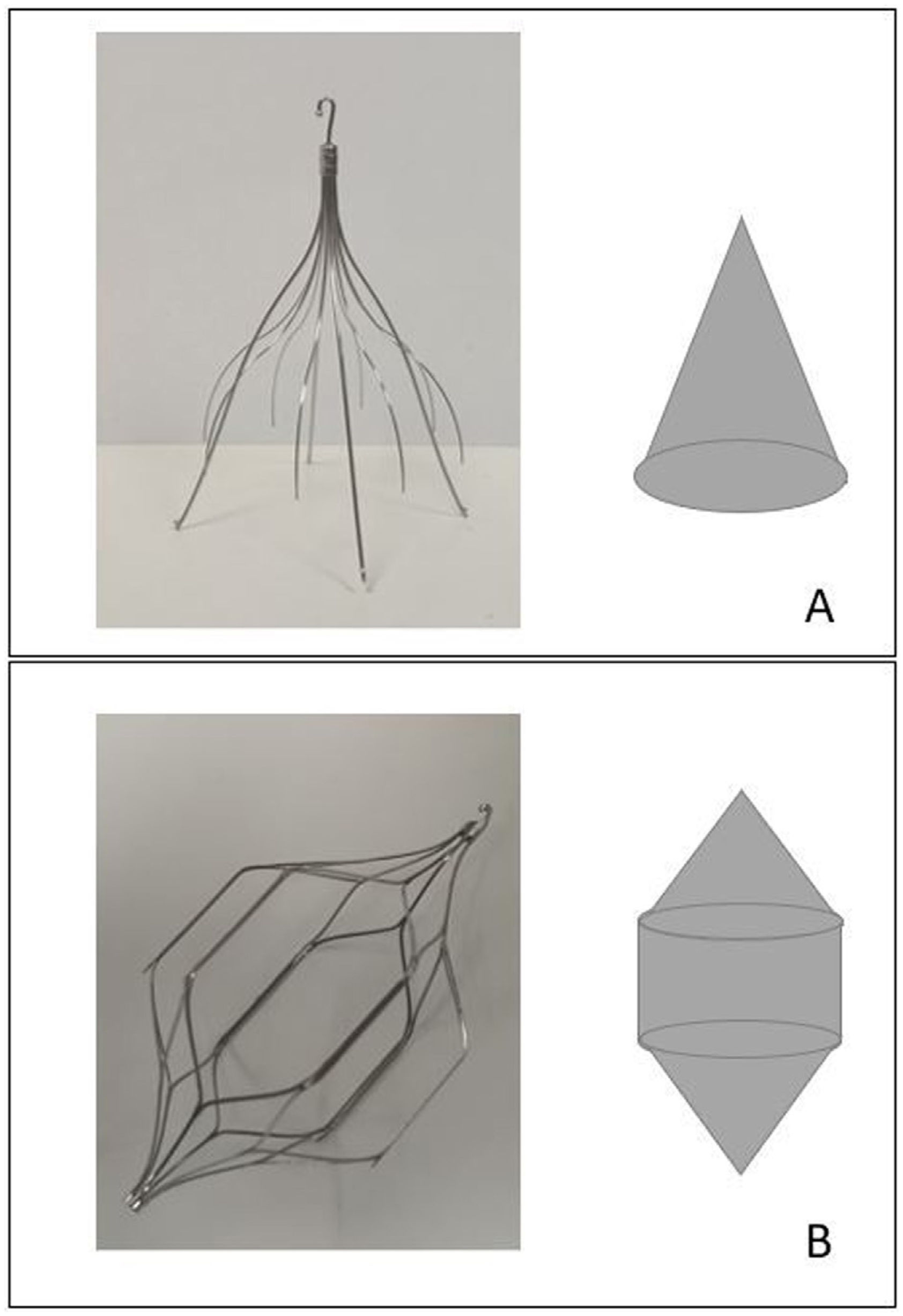

IVCF placement procedurePrior to the IVCF placement procedure, a specific ultrasound was performed to decide the site of venous access. The preferred access was through the right common femoral vein; in the event of thrombosis, access was through the left common femoral vein; in the event of bilateral femoral, bilateral iliac, or infrarenal vena cava thrombosis, access was through the right jugular vein and, in the event of thrombosis of that, through the left jugular vein. It should be noted that Celect Platinum® filters (Cook Medical, Bloomington, United States) can be released through femoral and jugular access sites, while the OptEase® filters (Cordis, Bridgewater, United States) available at our centre can only be released via a femoral access site.

The filters were released under fluoroscopic guidance in the angiography suites via the chosen venous access sites, with ultrasound-guided puncture and local anaesthetic. Before IVCF release, a phlebography was performed to assess IVC patency and its size, and to assess the anatomy and location of the renal veins.

The variables of the IVCF placement process analysed were: the type of IVCF, which was chosen at the discretion of the interventionist, between Celect Platinum® and OptEase® (Fig. 1); the access site (femoral/jugular); the side of access (right/left); and the location of the filter compared to the renal veins (suprarenal and infrarenal).

IVCF retrieval procedureIn anticoagulated patients, anticoagulation was discontinued prior to the IVCF retrieval procedure. The venous access site chosen for the retrieval procedure depended on the type of IVCF. The hook by which the Celect Platinum® IVCF are retrieved is at their cranial end, so the venous access to remove this type of device was through the right jugular vein (or left jugular vein in the case of thrombosis). In contrast, OptEase® filters have their hook for retrieval at their caudal end, so the access route chosen in patients with this type of device was through the right common femoral vein (or left in the case of thrombosis).

The procedure was carried out with local anaesthetic and venous access was granted by ultrasound-guided puncture. Before IVCF retrieval, phlebography was performed to rule out thrombosis. The retrieval set recommended by the manufacturer was used as the first option. The variables analysed for the retrieval procedure were the time (days) from placement to removal of the IVCF, and we analysed whether or not retrieval was carried out before or after 45 days, in accordance with local protocol. We reviewed the access site and side (femoral/jugular and right/left) used for the retrieval.

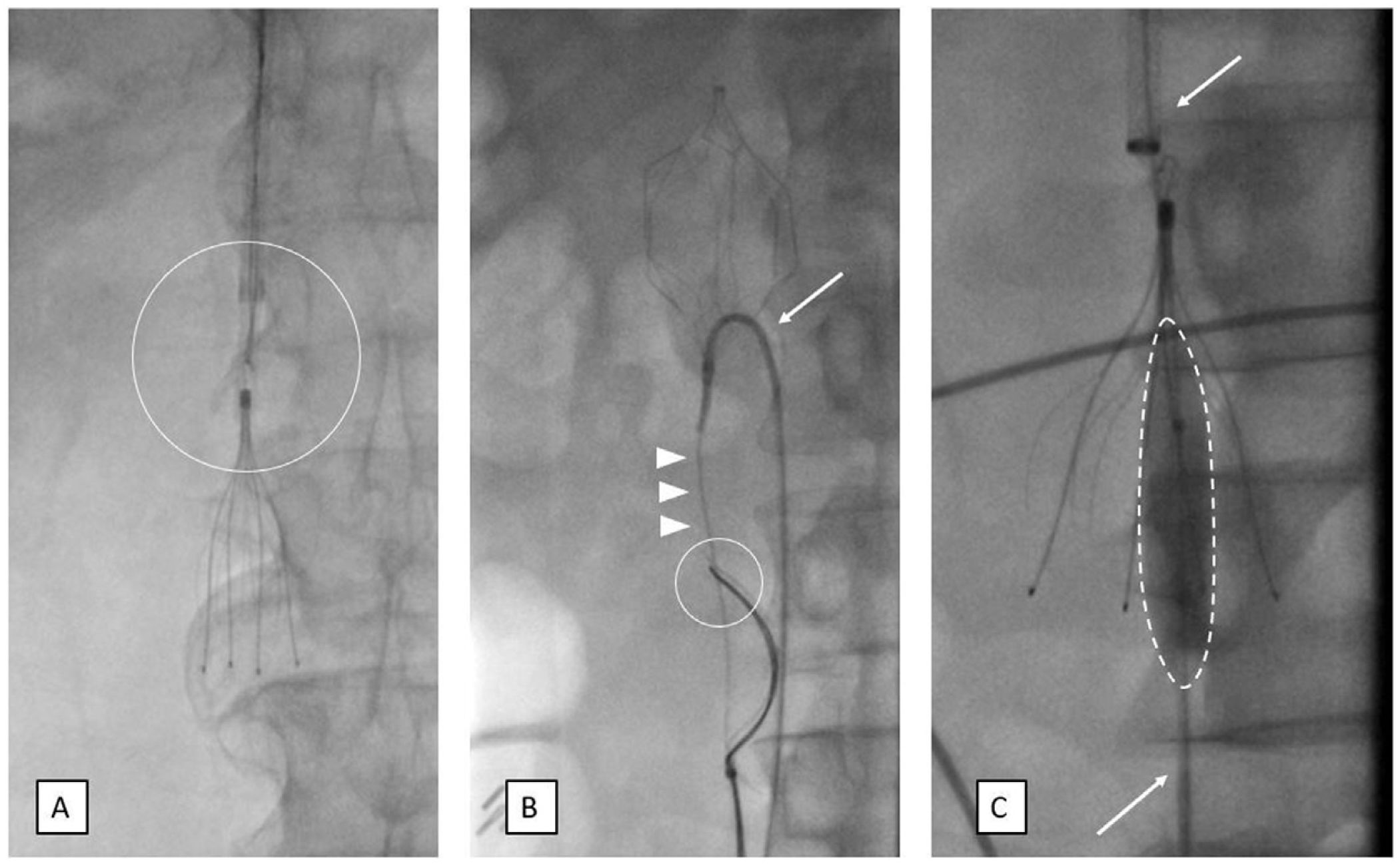

The standard technique described in the literature for the retrieval of IVCF is with a snare device. Other techniques have been described for cases of complex retrievals,16 such as that reported by Rubenstein et al.,17 which uses a reverse curve catheter inserted in between the filter elements, through which a guidewire is advanced, which is snared with a loop, with the actual guidewire acting as the loop. Other techniques used for complex retrievals are: the use of several guidewires and loops via two different venous access sites; the use of balloons to change the tilt of the filters; or dissection techniques using forceps (Fig. 2).

IVCF retrieval techniques. (A) Standard technique using snare (circle). (B and C) Additional material for complex retrievals (B); insertion of a reverse curve catheter between the filter components (arrow), through which a guidewire is advanced (arrowheads), which is snared with a loop (circle); double venous access (C) (arrows), use of a balloon (dashed line) to correct the tilt of the filter.

Therefore, when analysing the type of material used for IVCF removal in our cohort, it was classified as loop-snare versus additional material, defined as the supplementary use of various snares, balloons, catheters or forceps.

The efficacy variables were the procedure fluoroscopy time (measured in minutes), success retrieving the IVCF and the number of removal attempts.

Regarding safety variables, the occurrence of major peri-procedural complications was documented and classified according to the guidelines of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE)18 (grade 1: complication during the procedure that could be solved within the same session; no additional therapy, no post-procedure sequelae; grade 2: prolonged observation including overnight stay, no additional post-procedure therapy, no post-procedure sequelae; grade 3: additional post-procedure therapy or prolonged hospital stay >48 h required; grade 4: permanent mild sequelae; grade 5: permanent severe sequelae; grade 6: death).

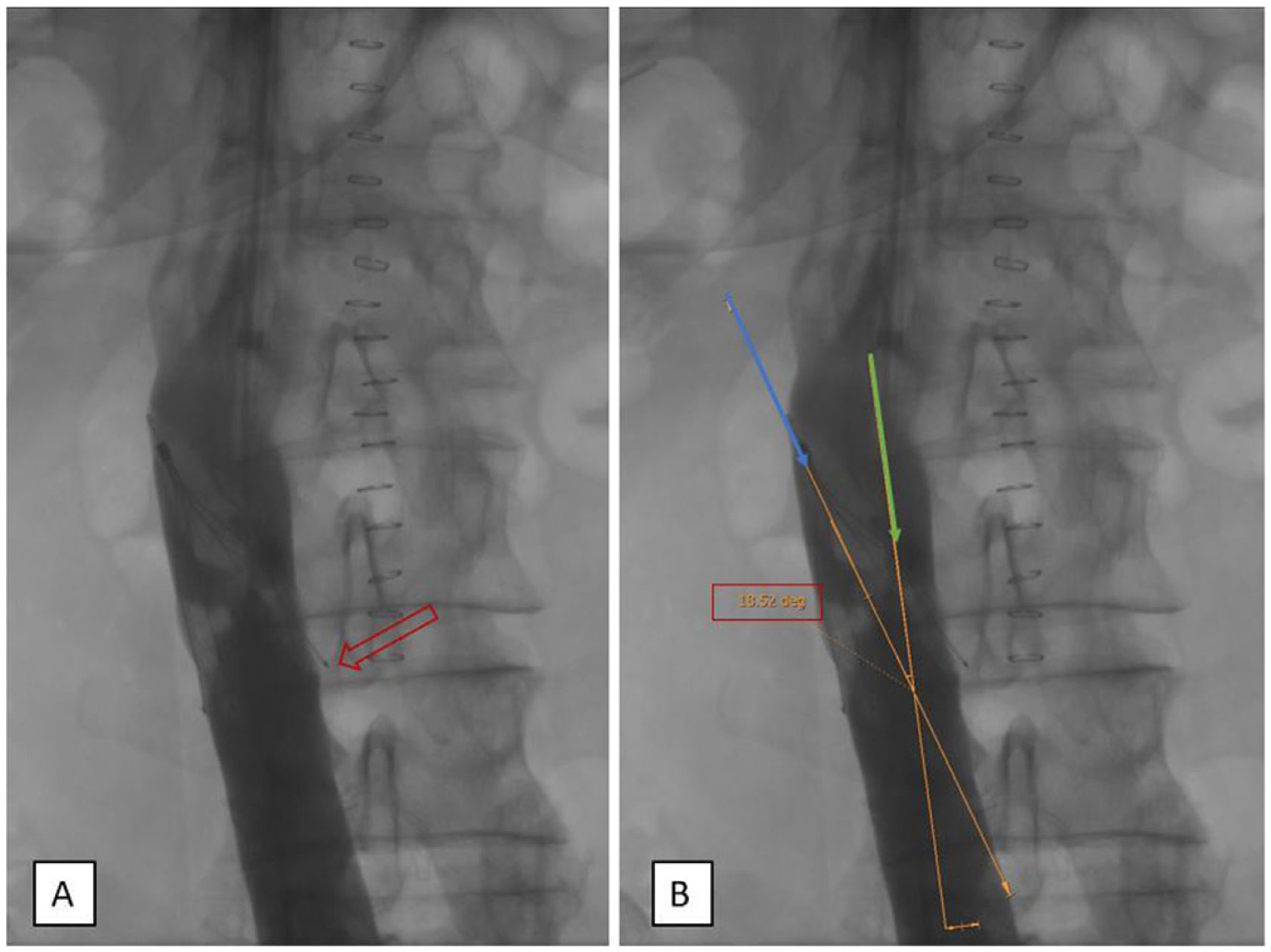

Radiological variablesRadiological variables were analysed by an experienced vascular and interventional radiologist, without access to the clinical information or the fluoroscopy time of the retrieval procedure. In each case, the angle at which the filter was tilted against the IVC wall was measured. To do this, on the initial cavogram a line was drawn parallel to the long axis of the IVC at the level of the filter and a second line through the apex of the filter, dividing it in two. Using the angle marking tool, the angulation of the IVCF was calculated (Fig. 3). The IVCF was considered tilted if the angle obtained was >15°.19 An assessment was made as to whether or not the legs of the IVCF were embedded and penetrating through the IVC wall >3 mm20 (Fig. 3). In terms of the position of the IVCF, we assessed whether the filter hook was in contact with or was leaning against the wall of the IVC (Fig. 4). All these variables were analysed in the phlebography images prior to retrieval, in anterior-posterior (AP) projection, as described in the literature. Computed tomography (CT) was not routinely performed before the filter retrieval procedure.

In the description of the sample, the mean and the standard deviation (SD) are used for quantitative variables or the median and the interquartile range (IQR) if they did not follow a normal distribution. The qualitative variables are characterised by the absolute and relative frequencies of each category.

For bivariate inferential studies, parametric tests were used whenever the normality of the variables involved in the analysis was demonstrated. Otherwise, non-parametric tests were used. For comparisons between two continuous variables, we used Student’s t-test for independent data or the Mann-Whitney test. Differences between proportions were analysed using Pearson’s chi-square test, applying Fisher’s exact test when the expected frequency was below 5.

Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Data were analysed using the SPSS25 program (Chicago, Illinois, United States).

The primary objective was to assess the factors associated with difficult removal, defined as cases in which more than one attempt was required for retrieval, or procedures requiring fluoroscopy times longer than the median for the overall sample (5 min).

We performed a univariate analysis between the difficult-removal and uncomplicated-removal groups, including demographic characteristics, comorbidities, cardiovascular risk factors, VTE risk factors, form of presentation, whether or not they were on anticoagulants, indication for filter placement and radiological characteristics of the IVCF retrieval. The radiological characteristics of the retrieval were analysed according to the type of IVCF.

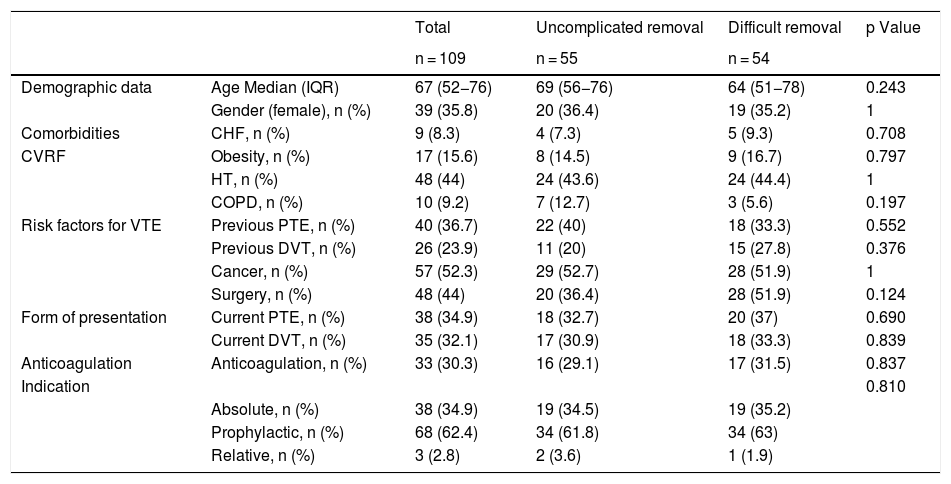

ResultsDuring the study period, 124 IVCF were removed, 109 of which met the criteria to be included in the study (Fig. 5). The main demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Univariate analysis. Demographic data, history, form of presentation, anticoagulant therapy, indication between the uncomplicated removal and difficult removal groups.

| Total | Uncomplicated removal | Difficult removal | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 109 | n = 55 | n = 54 | |||

| Demographic data | Age Median (IQR) | 67 (52−76) | 69 (56−76) | 64 (51−78) | 0.243 |

| Gender (female), n (%) | 39 (35.8) | 20 (36.4) | 19 (35.2) | 1 | |

| Comorbidities | CHF, n (%) | 9 (8.3) | 4 (7.3) | 5 (9.3) | 0.708 |

| CVRF | Obesity, n (%) | 17 (15.6) | 8 (14.5) | 9 (16.7) | 0.797 |

| HT, n (%) | 48 (44) | 24 (43.6) | 24 (44.4) | 1 | |

| COPD, n (%) | 10 (9.2) | 7 (12.7) | 3 (5.6) | 0.197 | |

| Risk factors for VTE | Previous PTE, n (%) | 40 (36.7) | 22 (40) | 18 (33.3) | 0.552 |

| Previous DVT, n (%) | 26 (23.9) | 11 (20) | 15 (27.8) | 0.376 | |

| Cancer, n (%) | 57 (52.3) | 29 (52.7) | 28 (51.9) | 1 | |

| Surgery, n (%) | 48 (44) | 20 (36.4) | 28 (51.9) | 0.124 | |

| Form of presentation | Current PTE, n (%) | 38 (34.9) | 18 (32.7) | 20 (37) | 0.690 |

| Current DVT, n (%) | 35 (32.1) | 17 (30.9) | 18 (33.3) | 0.839 | |

| Anticoagulation | Anticoagulation, n (%) | 33 (30.3) | 16 (29.1) | 17 (31.5) | 0.837 |

| Indication | 0.810 | ||||

| Absolute, n (%) | 38 (34.9) | 19 (34.5) | 19 (35.2) | ||

| Prophylactic, n (%) | 68 (62.4) | 34 (61.8) | 34 (63) | ||

| Relative, n (%) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.9) |

Difficult removal defined as >5 min fluoroscopy or >1 attempt at removal.

CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; HT: hypertension; IQR: interquartile range; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism; VTE: venous thromboembolism.

Of the patients included in the study, 72 (66.1%) had OptEase® devices implanted and 37 (33.9%), Celect®. In 91 cases (83.5%), access was obtained through the right femoral route for release, in 8 (7.3%) through the left femoral route and in 10 cases (9.2%) through the right jugular route. There were no cases of access through the left jugular vein. In 104 (95.4%) of the cases, the release was infrarenal, requiring an IVCF to be placed at the adrenal level in cases where the thrombosis affected the renal veins.

The median time until the removal of the IVCF was 36 days (IQR 27–66 days). The times until removal by indication for filter placement were as follows: 1. Absolute indication: n = 38, median time to removal 34.5 days (IQR 26.50–63.75); 2. Relative indication: n = 3, median time to removal 137 days (IQR 27–273 days); 3. Prophylactic indication: n = 68, median time to removal 36 days (IQR 26.25–64.50 days).

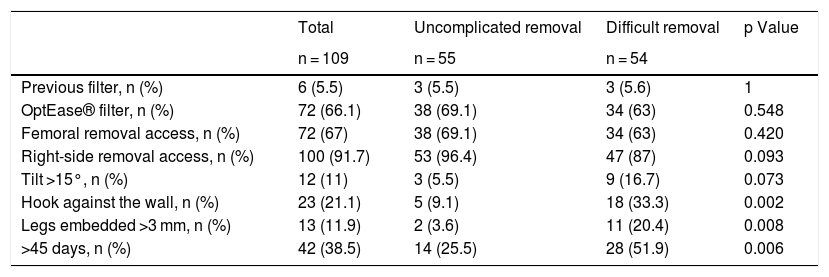

The primary access route for retrieval was right femoral, in 67 cases (61.5%), followed by right jugular in 33 (30.3%). The least common access routes were left femoral (6 [5.5%]) and left jugular (3 [2.8%]). In 13 cases (11.9%), additional material other than the snare was required for IVCF retrieval (more than one snare in 3 cases [23%]; balloon or MiniSimons in 6 cases [46.2%]; and forceps in 4 cases [30.8%]). The main radiological characteristics of the procedure are summarised in Table 2.

Univariate analysis. Characteristics of the IVCF removal procedure and radiological variables between the Uncomplicated-removal and Difficult-removal groups.

| Total | Uncomplicated removal | Difficult removal | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 109 | n = 55 | n = 54 | ||

| Previous filter, n (%) | 6 (5.5) | 3 (5.5) | 3 (5.6) | 1 |

| OptEase® filter, n (%) | 72 (66.1) | 38 (69.1) | 34 (63) | 0.548 |

| Femoral removal access, n (%) | 72 (67) | 38 (69.1) | 34 (63) | 0.420 |

| Right-side removal access, n (%) | 100 (91.7) | 53 (96.4) | 47 (87) | 0.093 |

| Tilt >15°, n (%) | 12 (11) | 3 (5.5) | 9 (16.7) | 0.073 |

| Hook against the wall, n (%) | 23 (21.1) | 5 (9.1) | 18 (33.3) | 0.002 |

| Legs embedded >3 mm, n (%) | 13 (11.9) | 2 (3.6) | 11 (20.4) | 0.008 |

| >45 days, n (%) | 42 (38.5) | 14 (25.5) | 28 (51.9) | 0.006 |

Difficult removal defined as >5 min fluoroscopy or >1 attempt at removal.

The median fluoroscopy time in the general cohort was 4.8 min (IQR 3–9.6 min). In patients with complex removal, the median fluoroscopy time was 21.5 min (IQR 6.8-24.1 min).

Five of the patients (4.6%) required more than one attempt at removal. The device could be removed in two of those five patients (40%). In seven of the patients overall (6.4%), the IVCF was ultimately not removed. In three of those patients (42.8%), more than one attempt was made to remove it and in four (57.1%), removal was decided against after the first attempt.

Of the seven IVCF which were ultimately not removed, six (85,7%) were OptEase® and for all seven (100%) the attempted removal was >45 days after placement. No complications associated with the procedure were recorded.

The univariate analysis is summarised in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found between the difficult-removal group and the uncomplicated-removal group in the demographic variables, comorbidities, cardiovascular risk factors, VTE risk factors, form of presentation, anticoagulant therapy or the indication. Regarding the radiological variables, the hook against the wall (p = 0.027), the legs embedded >3 mm in the IVC (p = 0.008) and time since placement >45 days (p = 0.006) were significantly more common in the difficult-removal group (Table 2).

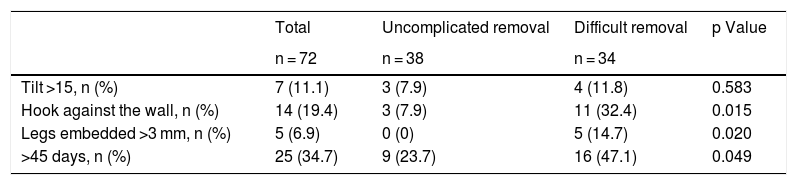

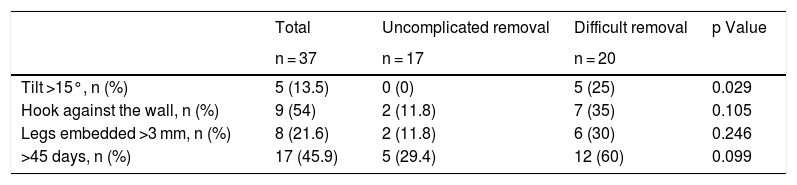

When analysing the radiological characteristics according to the type of filter (Tables 3 and 4), with the OptEase® IVCF, the presence of a hook against the wall (p = 0.05), legs embedded >3 mm in the IVC (p = 0.02) and time since placement >45 days (p = 0.049) were all associated with difficult removal. With the Celect® IVCF, statistically significant differences were observed in the tilting of the IVCF (>15°).

Univariate analysis of OptEase® IVCF subgroup radiological variables.

| Total | Uncomplicated removal | Difficult removal | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 72 | n = 38 | n = 34 | ||

| Tilt >15, n (%) | 7 (11.1) | 3 (7.9) | 4 (11.8) | 0.583 |

| Hook against the wall, n (%) | 14 (19.4) | 3 (7.9) | 11 (32.4) | 0.015 |

| Legs embedded >3 mm, n (%) | 5 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 5 (14.7) | 0.020 |

| >45 days, n (%) | 25 (34.7) | 9 (23.7) | 16 (47.1) | 0.049 |

Difficult removal defined as >5 min fluoroscopy or >1 attempt at removal.

Univariate analysis of Celect® IVCF subgroup radiological variables.

| Total | Uncomplicated removal | Difficult removal | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 37 | n = 17 | n = 20 | ||

| Tilt >15°, n (%) | 5 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (25) | 0.029 |

| Hook against the wall, n (%) | 9 (54) | 2 (11.8) | 7 (35) | 0.105 |

| Legs embedded >3 mm, n (%) | 8 (21.6) | 2 (11.8) | 6 (30) | 0.246 |

| >45 days, n (%) | 17 (45.9) | 5 (29.4) | 12 (60) | 0.099 |

Difficult removal defined as >5 min fluoroscopy or >1 attempt at removal.

This study retrospectively assessed the radiological variables associated with the difficulty in removing the IVCF. The main results of the study indicate that factors such as time since IVCF placement, legs embedded in the IVC wall and device hook contact with the IVC wall are all associated with difficult removal. When analysing the characteristics based on the type of IVCF, although we found the association of these variables with the OptEase® filters, we did not detect any such association with the Celect® filters, in this case finding that only tilting of more than 15° was associated with difficult removal of the IVCF.

Several authors have analysed the relationship between time since IVCF placement and retrieval success rate, but there continues to be considerable debate in the literature about the cut-off point for this variable. Geisbüsch et al.21 showed that the risk of unsuccessful removal was almost 20 times higher in IVCF indwelling for more than 90 days. Dinglasan et al.,15 however, took 180 days as the cut-off point, showing a 2.3-fold greater risk of complicated removal after that time. Another study suggested that the optimal time for the retrieval of the device ranges from 29 to 54 days after placement.22 Analysing the time until retrieval in our study, a relationship was found between difficult removal and IVCF implanted more than 45 days before. We found this association with the OptEase® but not with the Celect®. All this confirms, as stated in the specifications for each type of filter, that each one has an optimal time for retrieval and this factor needs to be analysed according to the type of IVCF. Based on the clinical experience described in the Instructions for use (IFU) for the OptEase® devices, it is specified that the filters can be safely removed up to 23 days after placement.23 The clinical experience described in the Celect® device IFU specifies that the likelihood of successful removal is 100% up to 26 weeks after placement.24

Longer times until IVCF retrieval are associated with IVCF components penetrating the IVC wall.25 This is a common but little-recognised complication of the filters. In 2015, a meta-analysis of 9,002 patients showed that in 19% of the cases some component of the IVCF penetrated the IVC wall.26 Dinglasan et al.15 showed that filters with a greater degree of perforation were associated with a 10-fold higher risk of complicated removal. In our study, an association was found between difficult removal and penetration of the legs in the IVC wall of more than 3 mm. We found this association when analysing the OptEase® subgroup, but not the Celect® subgroup.

Another radiological variable associated with difficult removal is the position of the IVCF hook close to or directly in contact with the IVC wall; this can cause venous intimal hyperplasia and endothelialisation of the device hook. For some authors, the hook against the IVC wall variable represents arguably the biggest challenge for IVCF removal, with supplementary material or more aggressive techniques being necessary in these cases.27 Kleedehn et al. demonstrated that this variable was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 59.8 (95% confidence interval [CI], 16.64–241.91) for complex removal.28 In our study, an association was found between the hook being against the IVC wall and difficult removal in the overall sample and in the OptEase® subgroup, but no such association was found in the Celect® subgroup. This could be because the hooks on the two devices are differently shaped or cause different reactions on the IVC wall.

The position of the hook against the IVC wall is often the result of tilting of the IVCF. Previous retrospective studies20,28 have reported that filters angled between 5 and 15° have a 2.4-fold increased risk of difficult removal (OR 2.38, 95% CI, 1.42–3.99, p = 0.001) and those tilted more than 15° are almost eight times more likely to be difficult to retrieve (OR 7.91, 95% CI, 2.9–21.6, p = 0.0001)20. It should be noted that in the sample evaluated by Clements et al.20 and Kleedehn et al.,28 all the filters analysed were cone-shaped. In our series, no statistically significant association was found when analysing this variable in the overall sample or in the OptEase® subgroup (cone-shaped at both ends with central cylindrical component). However, all cases of Celect® IVCF (cone-shaped) tilted more than 15° were difficult to remove, with the association being statistically significant. It is likely that the radiological variable of tilting of more than 15° makes it difficult to specifically remove cone-shaped devices.

Our study has the limitations of being a retrospective study from a single centre in which only two types of IVCF were used. Moreover, despite the three-dimensional nature of the procedure, all the radiological variables analysed are based on a 2D interpretation, although this is the interpretation method most commonly analysed in the literature. In order to overcome this limitation, some series in the literature use CT images to assess the radiological variables associated with difficult removal.15 Routine CT prior to the retrieval procedure is the subject of debate. According to the consensus of some guidelines,5,8 it is not recommended systematically but only in selected cases. The patients in whom performing a CT prior to the procedure would be justified needs to be standardised. The main strength of this work is our analysis according to the IVCF subtype and the detection of different factors associated with difficult removal depending on the type of filter. To confirm this hypothesis, meta-analyses would be necessary in which the retrieval variables were reviewed according to the type of IVCF.

Our study found an association between difficult removal and variables such as time since IVCF placement, the legs of the device being embedded in the IVC wall and contact of the device's hook with the IVC wall. When we analysed the OptEase® IVCF, the radiological variables of time since placement, embedded legs and hook against the wall were associated with difficulty in removing these devices. However, with the Celect® IVCF, the only radiological variable associated with difficulty in removal was tilt greater than 15°.

In conclusion, the variables associated with difficult IVCF removal depend on the type and shape of the IVCF, so they need to be analysed individually according to the type of device used.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: ES, FZ, CZM, JM, FMG and ALR.

- 2.

Study conception: ES, FZ, FMG and ALR.

- 3.

Study design: ES, EVT, FZ, FMG and ALR.

- 4.

Data collection: ES and EVT.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: ES, EVT, FZ, CZM, JM, FMG and ALR.

- 6.

Statistical processing: ES, EVT and ALR.

- 7.

Literature search: ES, EVT, FZ, CZM, JM, FMG and ALR.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: ES and ALR.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: ES, EVT, FZ, CZM, JM, FMG and ALR.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: ES, EVT, FZ, CZM, JM, FMG and ALR.

This research was not supported by any grant.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This research was not supported by any grant.

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

All the authors have read and approved the final version of the article.