A diaphragmatic hernia is the protrusion of abdominal tissues into the thoracic cavity secondary to a defect in the diaphragm. Reviewing the literature, we found only 44 references to diaphragmatic hernia secondary to percutaneous radiofrequency treatment. The vast majority of these cases were secondary to the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in segments V and VIII. Nevertheless, to date, this is the first reported case of diaphragmatic hernia after radiofrequency ablation of a liver metastasis from colorectal cancer. Complications secondary to diaphragmatic hernias are very diverse. The principal risk factor for complications is the contents of the hernia; when small bowel or colon segments protrude in the thoracic cavity, they can become incarcerated. Asymptomatic cases have also been reported in which the diaphragmatic hernia was discovered during follow-up. The pathophysiological mechanism is not totally clear, but it is thought that these diaphragmatic hernias might be caused by locoregional thermal damage. Given that most communications correspond to asymptomatic and/or treated cases, it is likely that the incidence is underestimated. However, due to the advent of percutaneous treatments, this complication might be reported more often in the future. Most cases are treated with primary herniorrhaphy, done with a laparoscopic or open approach at the surgeon’s discretion; no evidence supports the use of one approach over the other. Nevertheless, it seems clear that surgery is the only definitive treatment, as well as the treatment of choice if complications develop. However, in asymptomatic patients in whom a diaphragmatic hernia is discovered in follow-up imaging studies, management should probably be guided by the patient’s overall condition, taking into account the potential risks of complications (contents, diameter of the opening into the thoracic cavity …).

La hernia diafragmática (HD) es la protrusión de los tejidos abdominales a la cavidad torácica secundaria a un defecto en el diafragma. Tras una revisión de la bibliografía, únicamente se han identificado 44 referencias al respecto, donde se describen 35 casos de HD secundarias a tratamientos percutáneos con RF. En su gran mayoría son secundarias a lesiones por carcinoma hepatocelular en los segmentos V y VIII. No obstante, hasta la fecha, este es el primer caso comunicado de HD tras RF para el tratamiento de una metástasis hepática por CCR. Las complicaciones secundarias a las HD este es muy diversas. El principal factor de riesgo para ello es su contenido; así se describen casos incarceración de colon e intestino delgado. Igualmente, se describen casos asintomáticos en los que la HD ha sido un hallazgo en el seguimiento de los pacientes. El mecanismo fisiopatológico no está del todo esclarecido, pero se especula con la posibilidad de un daño térmico locorregional. Dado que la mayoría de las comunicaciones corresponden a casos sintomáticos y/o tratados, probablemente, la incidencia esté infraestimada. No obstante, debido al advenimiento de los tratamientos percutáneos, esta complicación podría verse comunicada en mayor número en los próximos años. Respecto a los tratamientos descritos, en la mayoría de los casos se ha optado por una herniorrafia primaria, con una vía de abordaje abierta o laparoscópica a discreción del cirujano. No se dispone evidencia que soporte ninguna actitud al respecto. Si bien, parece claro que el tratamiento quirúrgico es el único definitivo y el de elección en caso complicación. Sin embargo, en pacientes asintomáticos en quienes la HD sea un hallazgo radiológico de control, la actitud de manejo, quizá deba guiarse por el estado general del paciente, así como los riesgos potenciales de complicación (contenido, diámetro del orificio herniario…).

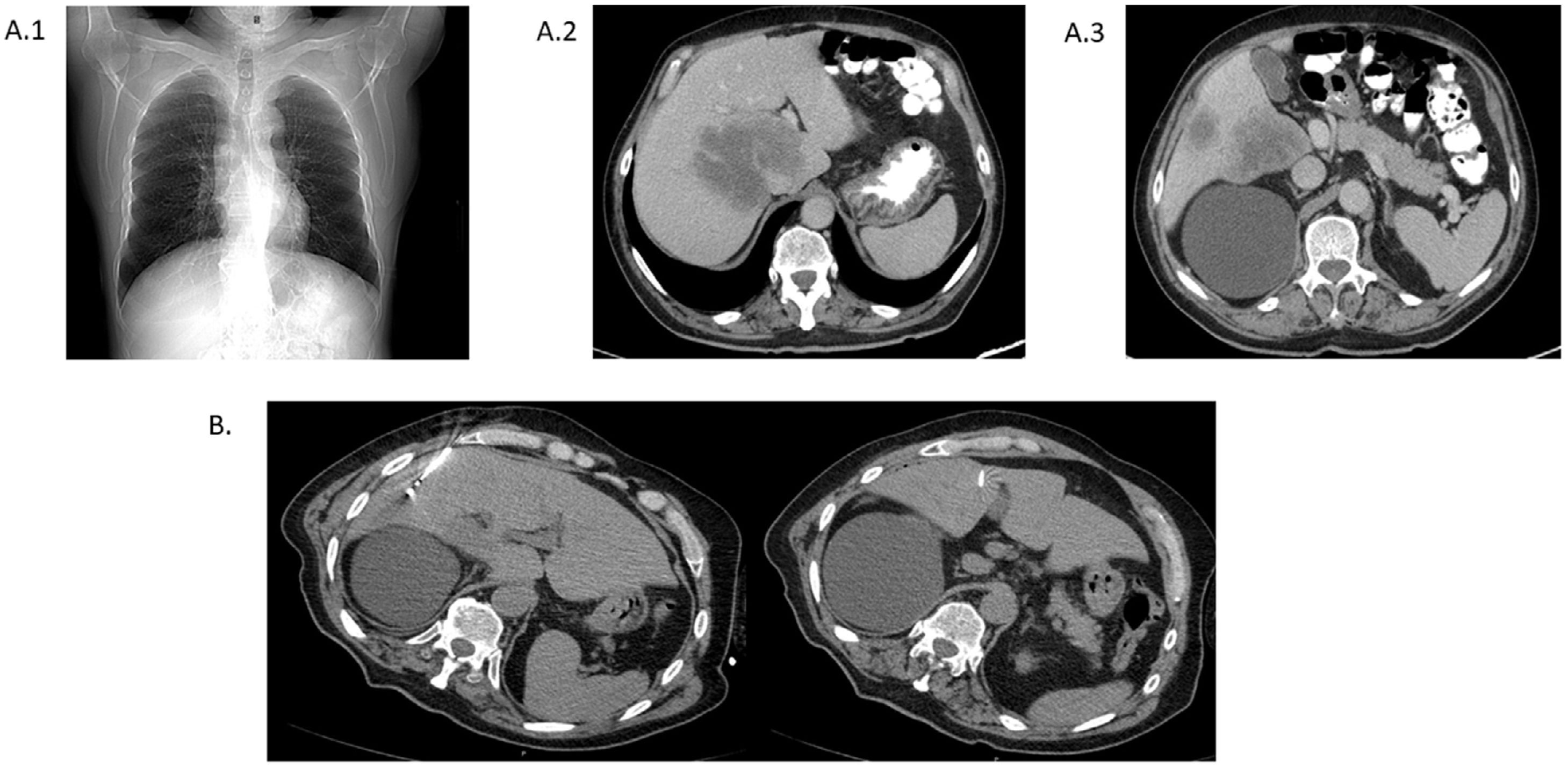

A 72-year-old man was diagnosed with stage IV KRAS wild-type adenocarcinoma of the rectum due to liver involvement (a lesion in a central location of 87 mm –initially considered surgically unresectable–, another in segment V of 33 mm and a third in segments V–VIII of 25 mm) in June 2018 (Fig. 1). First-line chemotherapy treatment was started with the FOLFIRI plus cetuximab regimen. After 10 cycles of chemotherapy, and with a partial response, in January 2019 combined radiofrequency (RF) treatment with radical intent was performed, guided by computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound, on lesions in segments V and V–VIII + SBRT (sterotactic body radiation therapy) with a total dose of 48 Gy on the lesion in a central location (Fig. 1). A slight increase in transaminases was detected after the procedure, which was asymptomatic.

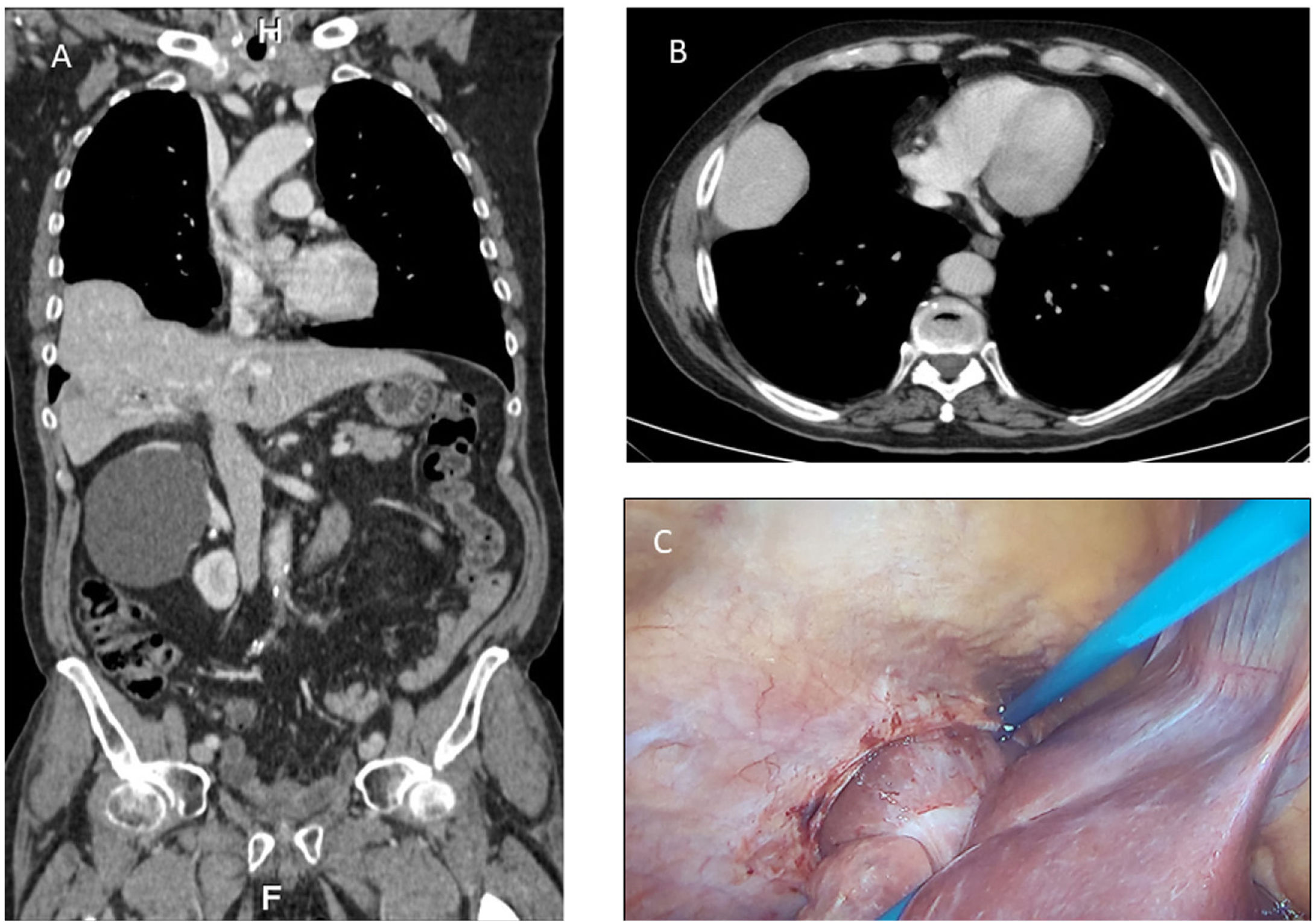

Subsequently, and after a short course of pelvic radiotherapy, an abdominoperineal resection was performed. In January 2020, a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan was performed during follow-up, revealing hepatic relapse with a single lesion in segments V–VIII, previously treated with RF. In an evaluation CT scan in April 2020, a completely asymptomatic diaphragmatic hernia (DH) liver content was identified, not detected in previous studies (Fig. 2). Maintaining the same previous chemotherapy regimen and after a sustained partial response, the case was submitted for re-evaluation by the liver metastasis committee.

Given the single hepatic relapse, with an adequate response to chemotherapy in a patient with ECOG 0, surgery was performed in March 2021. Through laparoscopic access with four trocars, the abdominal cavity was accessed, a lesion in segment V was identified, and a DH partially contained the right hepatic lobe (Fig. 2).

Following intraoperative ultrasound, a segmental resection of segment V was performed along with the gallbladder en bloc. No progressive incidents were recorded.

DiscussionAlthough surgical resection of liver lesions is the treatment of choice in patients with resectable colorectal cancer (CRC) metastases, radiofrequency ablation is one of the current therapeutic options contributing to survival in patients with non-resectable lesions or those who are not candidates for surgery.1 Although it is a safe and minimally invasive technique, complications such as vascular injury, haemorrhage, abscesses, biliary fistula, pneumothorax, liver failure and, much less frequently, diaphragmatic hernia have been described.2

DH, in general terms, is the protrusion of the abdominal tissues into the thoracic cavity secondary to a defect in the diaphragm. While congenital hernia is the most common manifestation, acquired DH is a rare form of presentation that occurs after diaphragmatic rupture due to thoracoabdominal trauma or iatrogenic injury.3

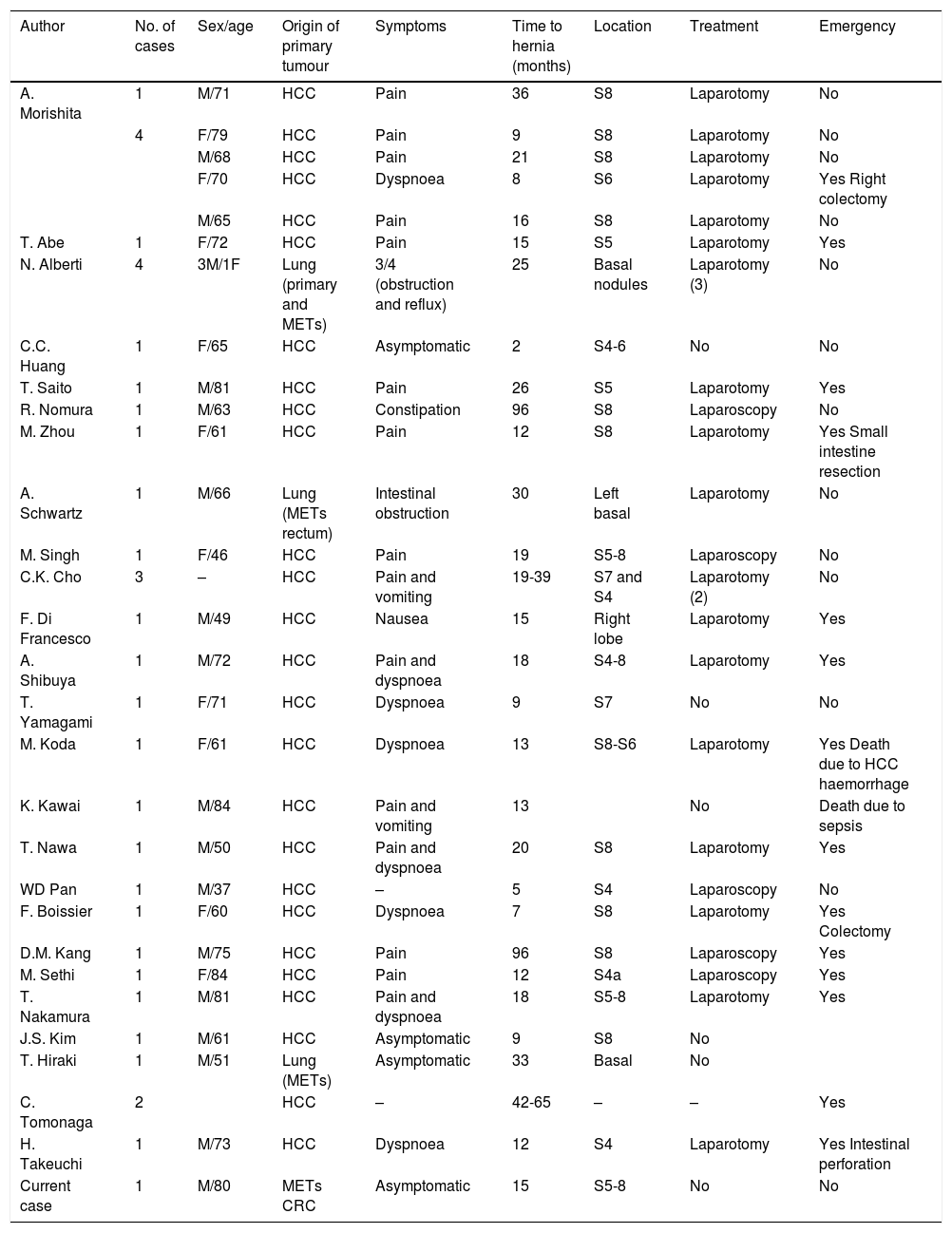

After a review of the literature available in the central databases (PubMed-MEDLINE, Google Scholar, EMBASE) with the terms Diaphragmatic hernia AND Radiofrequency, only 44 references were identified in this regard, where 35 cases of DH secondary to percutaneous RF treatments have been described. Most are secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma lesions in segments V and VIII.4,5 In addition, six cases of DH after RF were found to treat basal lung lesions.6 There is also a publication7 that relates SBRT treatment for liver lesions and the appearance of DH. Table 1 contains a summary of the cases reported in the literature.

Summary of cases of diaphragmatic hernia in the literature.

| Author | No. of cases | Sex/age | Origin of primary tumour | Symptoms | Time to hernia (months) | Location | Treatment | Emergency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Morishita | 1 | M/71 | HCC | Pain | 36 | S8 | Laparotomy | No |

| 4 | F/79 | HCC | Pain | 9 | S8 | Laparotomy | No | |

| M/68 | HCC | Pain | 21 | S8 | Laparotomy | No | ||

| F/70 | HCC | Dyspnoea | 8 | S6 | Laparotomy | Yes Right colectomy | ||

| M/65 | HCC | Pain | 16 | S8 | Laparotomy | No | ||

| T. Abe | 1 | F/72 | HCC | Pain | 15 | S5 | Laparotomy | Yes |

| N. Alberti | 4 | 3M/1F | Lung (primary and METs) | 3/4 (obstruction and reflux) | 25 | Basal nodules | Laparotomy (3) | No |

| C.C. Huang | 1 | F/65 | HCC | Asymptomatic | 2 | S4-6 | No | No |

| T. Saito | 1 | M/81 | HCC | Pain | 26 | S5 | Laparotomy | Yes |

| R. Nomura | 1 | M/63 | HCC | Constipation | 96 | S8 | Laparoscopy | No |

| M. Zhou | 1 | F/61 | HCC | Pain | 12 | S8 | Laparotomy | Yes Small intestine resection |

| A. Schwartz | 1 | M/66 | Lung (METs rectum) | Intestinal obstruction | 30 | Left basal | Laparotomy | No |

| M. Singh | 1 | F/46 | HCC | Pain | 19 | S5-8 | Laparoscopy | No |

| C.K. Cho | 3 | – | HCC | Pain and vomiting | 19-39 | S7 and S4 | Laparotomy (2) | No |

| F. Di Francesco | 1 | M/49 | HCC | Nausea | 15 | Right lobe | Laparotomy | Yes |

| A. Shibuya | 1 | M/72 | HCC | Pain and dyspnoea | 18 | S4-8 | Laparotomy | Yes |

| T. Yamagami | 1 | F/71 | HCC | Dyspnoea | 9 | S7 | No | No |

| M. Koda | 1 | F/61 | HCC | Dyspnoea | 13 | S8-S6 | Laparotomy | Yes Death due to HCC haemorrhage |

| K. Kawai | 1 | M/84 | HCC | Pain and vomiting | 13 | No | Death due to sepsis | |

| T. Nawa | 1 | M/50 | HCC | Pain and dyspnoea | 20 | S8 | Laparotomy | Yes |

| WD Pan | 1 | M/37 | HCC | – | 5 | S4 | Laparoscopy | No |

| F. Boissier | 1 | F/60 | HCC | Dyspnoea | 7 | S8 | Laparotomy | Yes Colectomy |

| D.M. Kang | 1 | M/75 | HCC | Pain | 96 | S8 | Laparoscopy | Yes |

| M. Sethi | 1 | F/84 | HCC | Pain | 12 | S4a | Laparoscopy | Yes |

| T. Nakamura | 1 | M/81 | HCC | Pain and dyspnoea | 18 | S5-8 | Laparotomy | Yes |

| J.S. Kim | 1 | M/61 | HCC | Asymptomatic | 9 | S8 | No | |

| T. Hiraki | 1 | M/51 | Lung (METs) | Asymptomatic | 33 | Basal | No | |

| C. Tomonaga | 2 | HCC | – | 42-65 | – | – | Yes | |

| H. Takeuchi | 1 | M/73 | HCC | Dyspnoea | 12 | S4 | Laparotomy | Yes Intestinal perforation |

| Current case | 1 | M/80 | METs CRC | Asymptomatic | 15 | S5-8 | No | No |

CRC: colorectal cancer; F: female; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; M: male; METs metastases; S: segment.

However, to date, this is the first reported case of DH after percutaneous treatment for liver metastasis due to CRC.

Complications secondary to DH are very diverse. The main risk factor is its content; thus, cases of incarceration of the colon and small intestine are described.7,8

Likewise, asymptomatic cases are described in which DH has been a finding in the follow-up of patients.9

The pathophysiological mechanism is not completely clear, but the possibility of locoregional thermal injury has been speculated.7

Most reports correspond to symptomatic and/or treated cases, so the incidence is probably underestimated. However, due to the increased use of percutaneous treatments, this complication could be reported in more significant numbers in the coming years. Regarding the treatments described, in most cases, a primary herniorrhaphy has been opted for, with an open or laparoscopic approach at the surgeon’s discretion.10

In our case, due to the content of the hernia, its asymptomatic nature, the patient’s age, and the fact that it did not hinder the resection of the metastatic lesion, no treatment was performed on it, opting for evolutionary control.

There is no evidence to support any approach in this regard, although it seems clear that surgical treatment is the only definitive treatment and the one of choice in case of complication. In asymptomatic patients, management must be individualised, taking into account the risk of complications (content and diameter of the hernia sac, etc.) and the patient’s clinical situation.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: LDJ

- 2

Study conception: RP

- 3

Study design: LDJ

- 4

Data acquisition: LDJ, RP

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: LDJ, JN

- 6

Statistical processing: LDJ, JN

- 7

Literature search: LDJ, JN

- 8

Drafting of the article: LDJ, JN

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: LDJ, RP

- 10

Approval of the final version: LDJ, JN, JN, RP

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.