Patients attending the emergency department (ED) with cervical inflammatory/infectious symptoms or presenting masses that may involve the aerodigestive tract or vascular structures require a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck. Its radiological interpretation is hampered by the anatomical complexity and pathophysiological interrelationship between the different component systems in a relatively small area.

Recent studies propose a systematic evaluation of the cervical structures, using a 7-item checklist, to correctly identify the pathology and detect incidental findings that may interfere with patient management.

As a conclusion, the aim of this paper is to review CT findings in non-traumatic pathology of the neck in the ED, highlighting the importance of a systematic approach in its interpretation and synthesis of a structured, complete, and concise radiological report.

A los pacientes que acuden a urgencias con síntomas inflamatorio/infecciosos a nivel cervical o con masas que pueden comprometer el tracto aerodigestivo o las estructuras vasculares, es necesario hacerles una tomografía computarizada (TC) de cuello con contraste. Su interpretación radiológica se ve dificultada por la complejidad anatómica y la interrelación fisiopatológica entre los diferentes sistemas que lo componen, en un área de estudio relativamente pequeña.

Estudios recientes proponen realizar una evaluación sistemática de las estructuras cervicales, utilizando para ello un listado de verificación de 7 elementos, para identificar correctamente la patología, y detectar los hallazgos incidentales que pueden interferir en el manejo del paciente.

El objetivo de este trabajo es revisar los hallazgos de la TC en la patología no traumática del cuello en urgencias siguiendo una lectura sistemática, tras la cual se pueda realizar un informe radiológico estructurado, completo y conciso.

Patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with inflammatory/infectious symptoms at the cervical level or with masses that may involve the aerodigestive tract or vascular structures require a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck, which has a sensitivity of approximately 87% for detecting pathology.1

The protocol should include at least from the roof of the orbit to the aortic arch, and should be performed with intravenous contrast with venous phase acquisition: 80–100 ml, flow rate 2 ml/s and minimum acquisition delay 60 s. If an arterial phase is required (e.g. to rule out thrombosis or vascular invasion) a first acquisition can be performed locating a region of interest (ROI) in the aortic arch and a flow rate of 4 ml/s. In children, the contrast dose should be adjusted to 1.5 ml/kg.

However, the interpretation of the CT scan can be difficult, as the neck is a small, complex anatomical area containing very varied structures. It is therefore important to have a good knowledge of the anatomy of the cervical spaces in order to recognise asymmetries and assess the deviation of the different elements. In order to detect the various pathologies, a systematic and structured evaluation of all imaging findings is necessary.2 In addition, knowledge of the pathophysiological process of the various diseases will help us in the differential diagnosis that will allow us to establish a definitive diagnosis.

The aim of this paper is to propose a checklist as a guide for the systematic assessment of neck CT in non-traumatic emergencies, and to review through images the findings of the main pathologies that may be encountered. It is composed of the following 7 elements:

- 1.

Skin and subcutaneous cellular tissue.

- 2.

Teeth.

- 3.

Aerodigestive tract.

- 4.

Spaces: pneumatic and vascular.

- 5.

Glands: thyroid and salivary glands.

- 6.

Nervous system: brain, orbits and spinal cord.

- 7.

Upper thorax: lung apices and mediastinum.

This may be the source or an indicator of adjacent inflammation, and includes:

- •

The skin.

- •

Subcutaneous cellular tissue fat.

- •

The platysma and facial muscles.

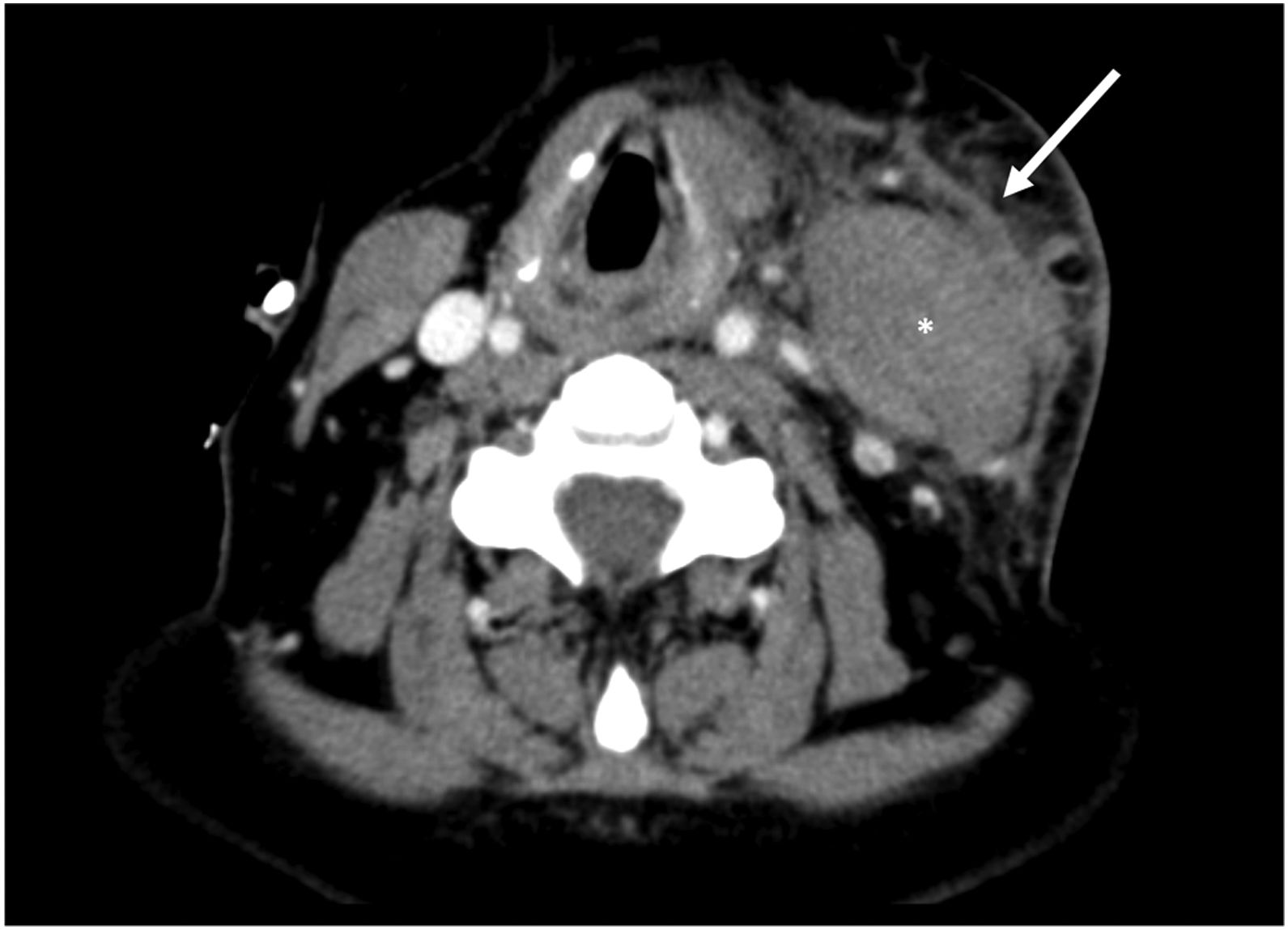

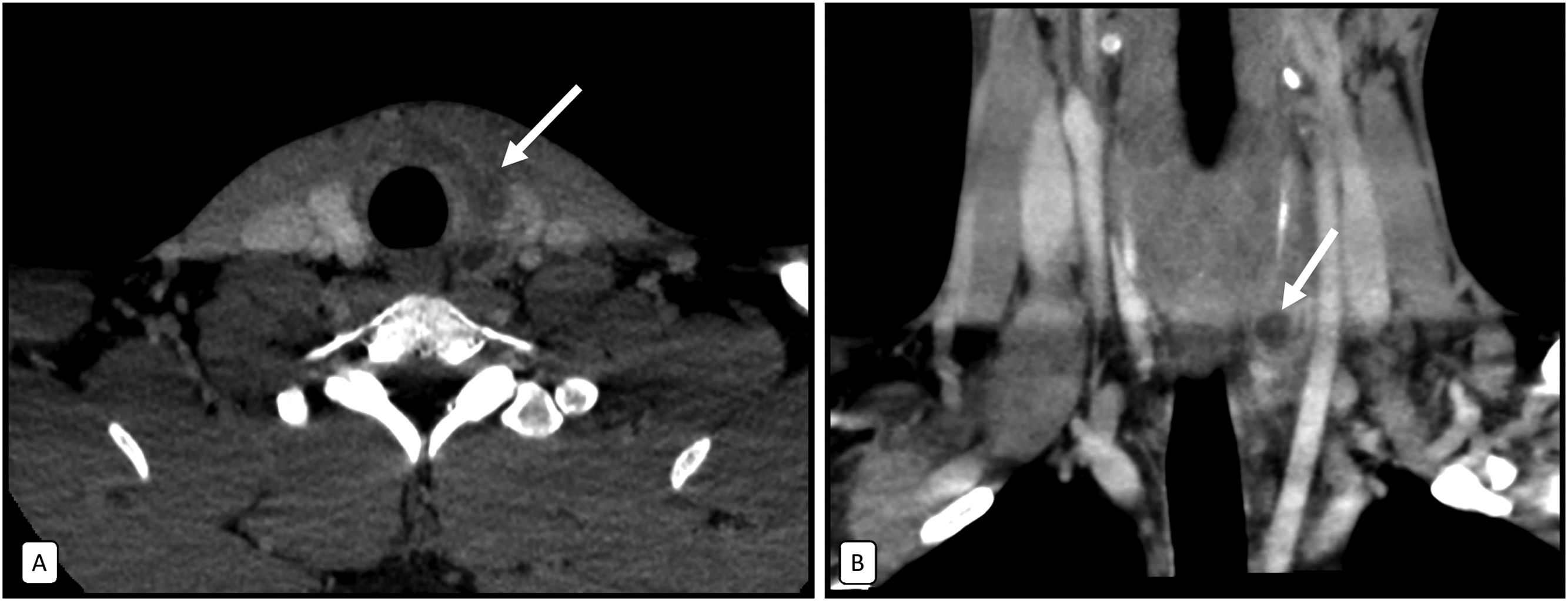

Cellulitis (Fig. 1) is often associated with chronic skin diseases, follicle infections, foreign bodies or microtraumas. The presence of drainable collections should be assessed. There are mimics with similar radiological findings that should be taken into account, e.g. intradermal injection of substances in the context of aesthetic treatments.

Cervical cellulitis, superficial fasciitis and myositis. A 50-year-old male with tumour and neck pain, with no history of trauma. There is a marked enlargement of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle (asterisk), with trabeculation of the adjacent fat and thickening of the superficial cervical fascia and platysma (arrow).

If the infection extends to deeper levels, we may find associated fasciitis and myositis (Fig. 1), with thickening of these structures and loss of the fat separation planes.3

Although the diagnosis of otitis externa is usually clinical, malignant otitis externa in elderly diabetics, which is associated with bone erosion, and osteomyelitis of the external auditory canal and the pinna, with possible infiltration of the soft tissues of the skull base and nasopharynx, should be considered in this section.

TeethPrimary causes of odontogenic infection include:

- •

Caries: defect or canal in the enamel.

- •

Periodontal disease: gingival inflammation.

- •

Pericoronitis: inflammation of the tissue around the third molar, usually due to food entrapment under the gum.

The inflammatory process can spread to adjacent structures causing odontogenic sinusitis and periodontal abscesses. It is important to identify them in order to drain them and prevent their spread to the deep spaces of the neck.4

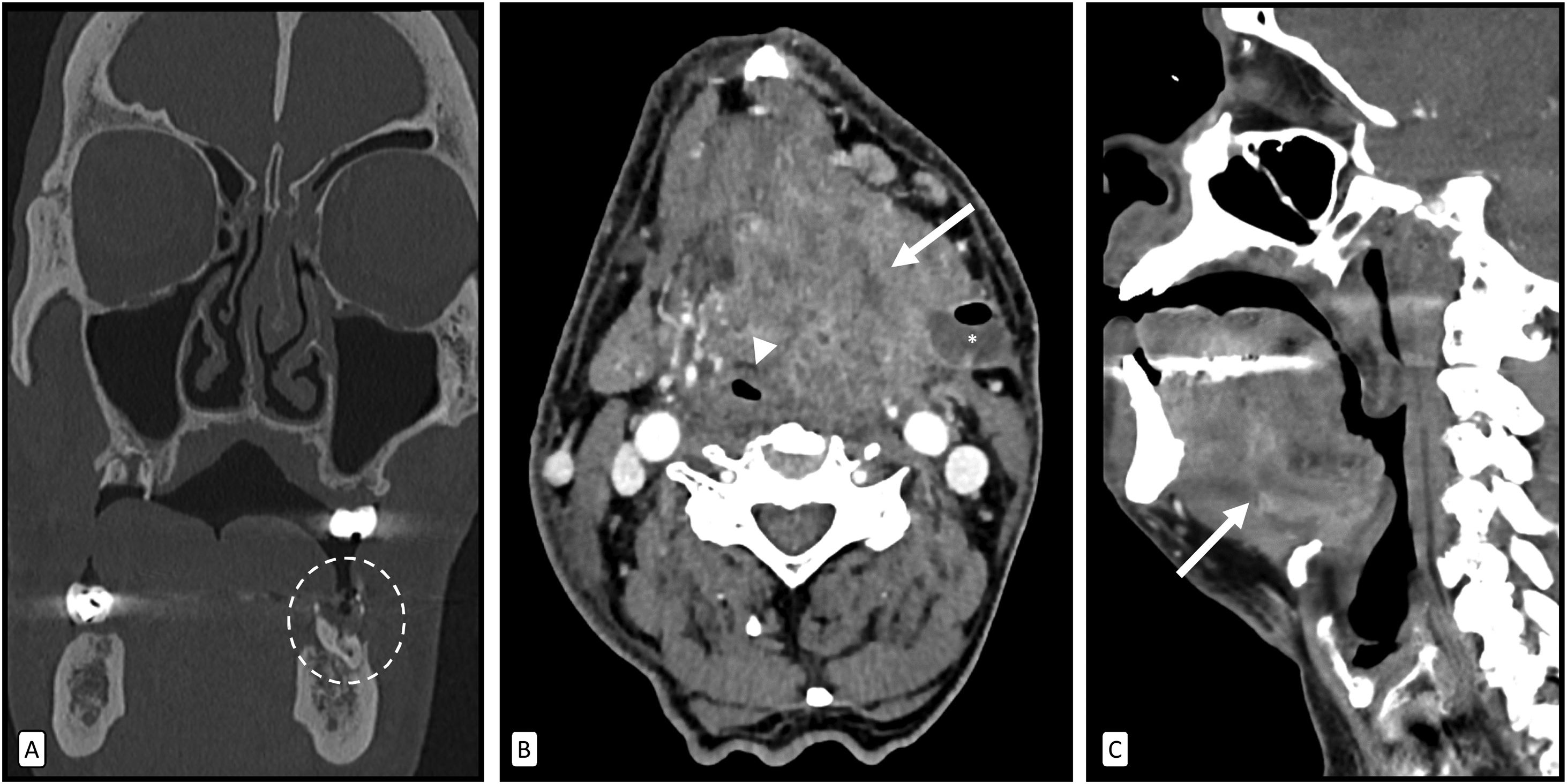

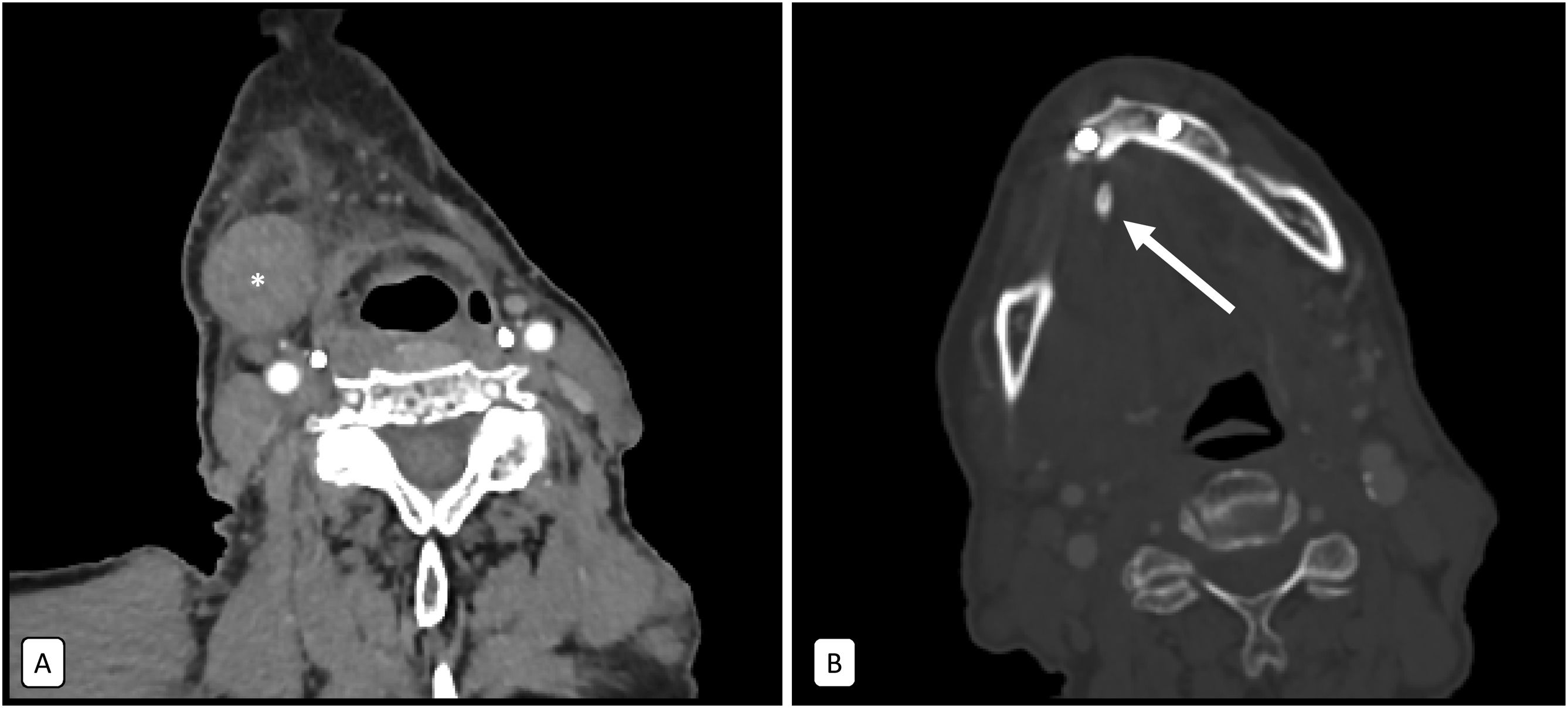

Ludwig’s angina (Fig. 2) is the most feared complication of dental infections and can lead to airway obstruction at the level of the oropharynx. It can occur due to odontogenic infections, after dental extractions of the second and third molars (as their roots extend below the insertion of the mylohyoid muscle) and less frequently after oral piercings.5

Ludwig angina. A 64-year-old male with poor dental hygiene and loss of several teeth, reporting fever, pain and swelling in the floor of the mouth. The coronal image with bone window (A) showing a marked interruption of the bone enamel in teeth 17 and 38, highlighting in the latter an occupation by hydroaerial material (circle). Axial (B) and sagittal (C) contrast-enhanced CT images showing involvement of the sublingual and submandibular spaces, with marked soft tissue enlargement centred on the left side of the floor of the mouth (arrows), with fat trabeculation and muscle thickening. There is also some rim enhancement suggestive of abscess (asterisk). Note the associated mass effect, leading to significant obliteration of the pharyngeal lumen (arrowhead).

It should be remembered that the detection of fat trabeculation and fluid bands in the sublingual and submandibular spaces is sufficient to establish the diagnosis, with or without abscesses or gas, with adenopathy being uncommon.

For odontogenic abscesses, the report should include:

- •

Original tooth.

- •

Spread of infection.

- •

Presence of drainable collections.

- •

Mass effect on the airway.

Assess craniocaudally from the oral and nasal cavity to the distal portions of the trachea and oesophagus, looking for masses, mucosal thickening, asymmetries and enhancements.

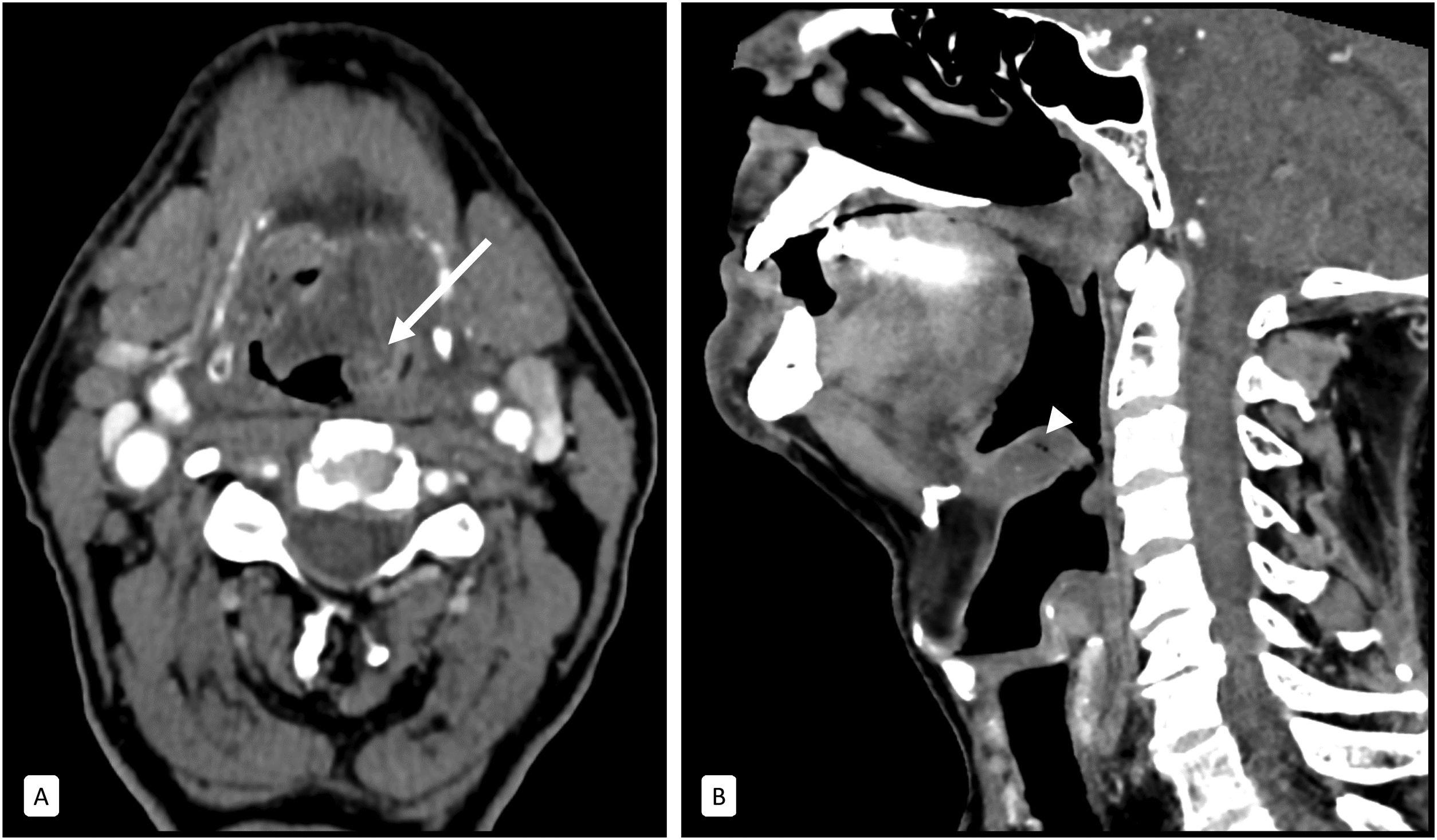

Tonsillitis is common, especially in children. It is useful to differentiate phlegmonous involvement from an abscess, whether tonsillar, peritonsillar (Fig. 3) or even retrotonsillar. The latter is located in the posterior pillar, displacing the tonsil anteriorly, and is more dangerous because of its anatomical location in the vicinity of the vessels and because it is accompanied by oedema, which can quickly spread to the epiglottic vallecula, epiglottis and aryepiglottic fold.

Tonsillitis with peritonsillar abscess. A 44-year-old man with odynophagia. Asymmetric thickening of the left palatine tonsil with a hypodense collection adjacent to its lateral border with peripheral enhancement (arrow). There are also phlegmonous changes in the left parapharyngeal space and slight bulging over the pharyngeal lumen.

It should be remembered that clinical airway management takes priority over imaging. Once this has been done, the patency and calibre of the airway must be assessed, with special attention to pathologies that reduce it, such as epiglottitis/supraglottitis (Fig. 4).

Acute epiglottitis. A 71-year-old male with acute respiratory failure. Asymmetric thickening of the epiglottis (arrow), with phlegmonous changes and oedema in the left epiglottic vellecula and perilaryngeal fat. A small central, more hypodense area with an air microbubble can be identified, probably related to incipient abscessification (arrowhead).

Pharyngo-oesophageal foreign body impaction occurs most frequently inferiorly to the cricopharyngeus muscle (at the C6 level) and mostly due to fish bones (60%) and chicken bones (16%).6 Indirect signs of perforation (extraluminal gas or fluid) and the presence of collections should be investigated.

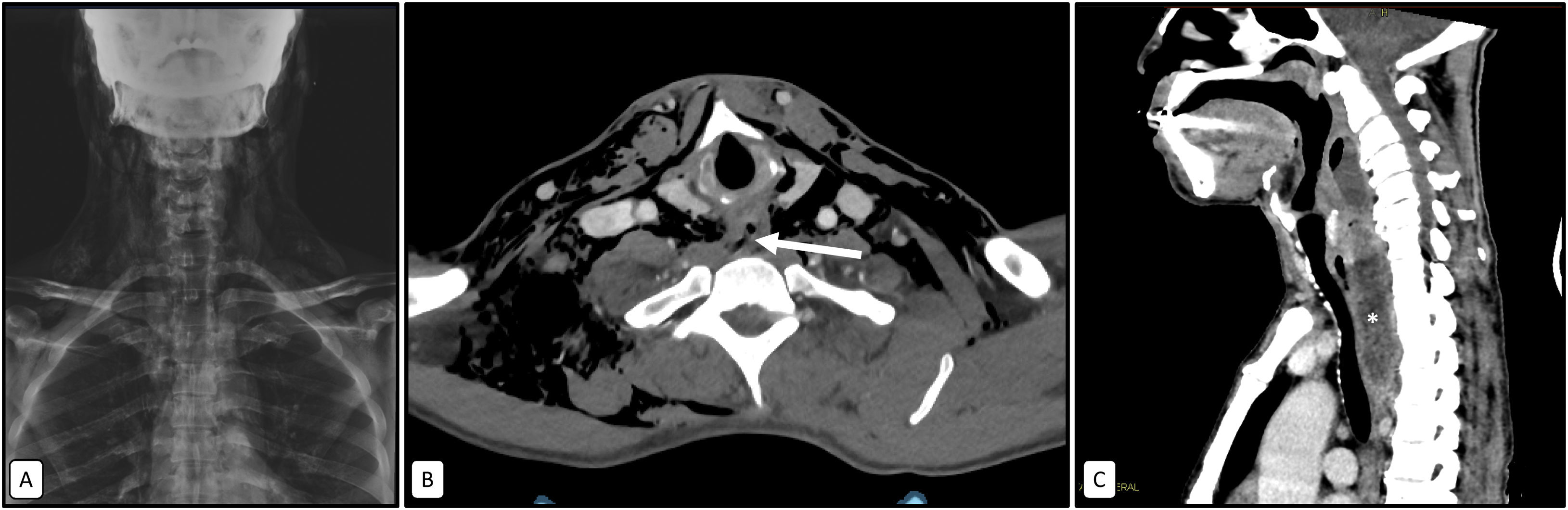

Retropharyngeal abscesses frequently originate from the extension of an oral or cervical infection with lymphatic drainage into the retropharyngeal nodes, however, they can also occur following discitis or osteomyelitis or from direct inoculation following oesophageal perforation or penetrating trauma. It is important to recognise them as they may extend into the mediastinum through the danger space (Fig. 5).

Esophageal perforation after foreign body impaction episode and subsequent complication with retropharyngeal abscess. A 56-year-old male attended the emergency department with sialorrhoea, dysphagia and pharyngeal foreign body sensation after choking on a chicken bone. Initial X-ray (A) showing marked subcutaneous and deep cervical emphysema. The axial image (B) of the contrast-enhanced CT scan confirms the findings seen on plain radiography and shows concentric parietal thickening of the proximal oesophagus, with a solution of continuity of its posterior wall (arrow). In the sagittal image (C) of the post-surgical control CT scan at 4 weeks, the presence of a retropharyngeal collection (asterisk) with extension into the upper mediastinum through the danger space can be observed as a complication.

Mucoperiosteal thickening or air-fluid levels are observed in up to 44% of imaging studies in adults, reflecting inflammatory changes that are generally non-specific and may persist for more than 8 weeks, and should therefore never be labelled as acute sinusitis, and should always be correlated clinically.7 In fact, special attention should be paid in diabetic or neutropenic patients because of the possibility of developing invasive fungal sinusitis, where hyperattenuating pseudomas can be visualised eroding the bony margin of the sinus.

Regarding complications of acute sinusitis, it is important to assess periantral fat infiltration as an indicator of invasion of adjacent structures:

- •

Orbital: subperiosteal abscesses and orbital cellulitis.

- •

Soft tissues: Pott Puffy Tumour.8

- •

Intracranial.

- •

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (Fig. 6).

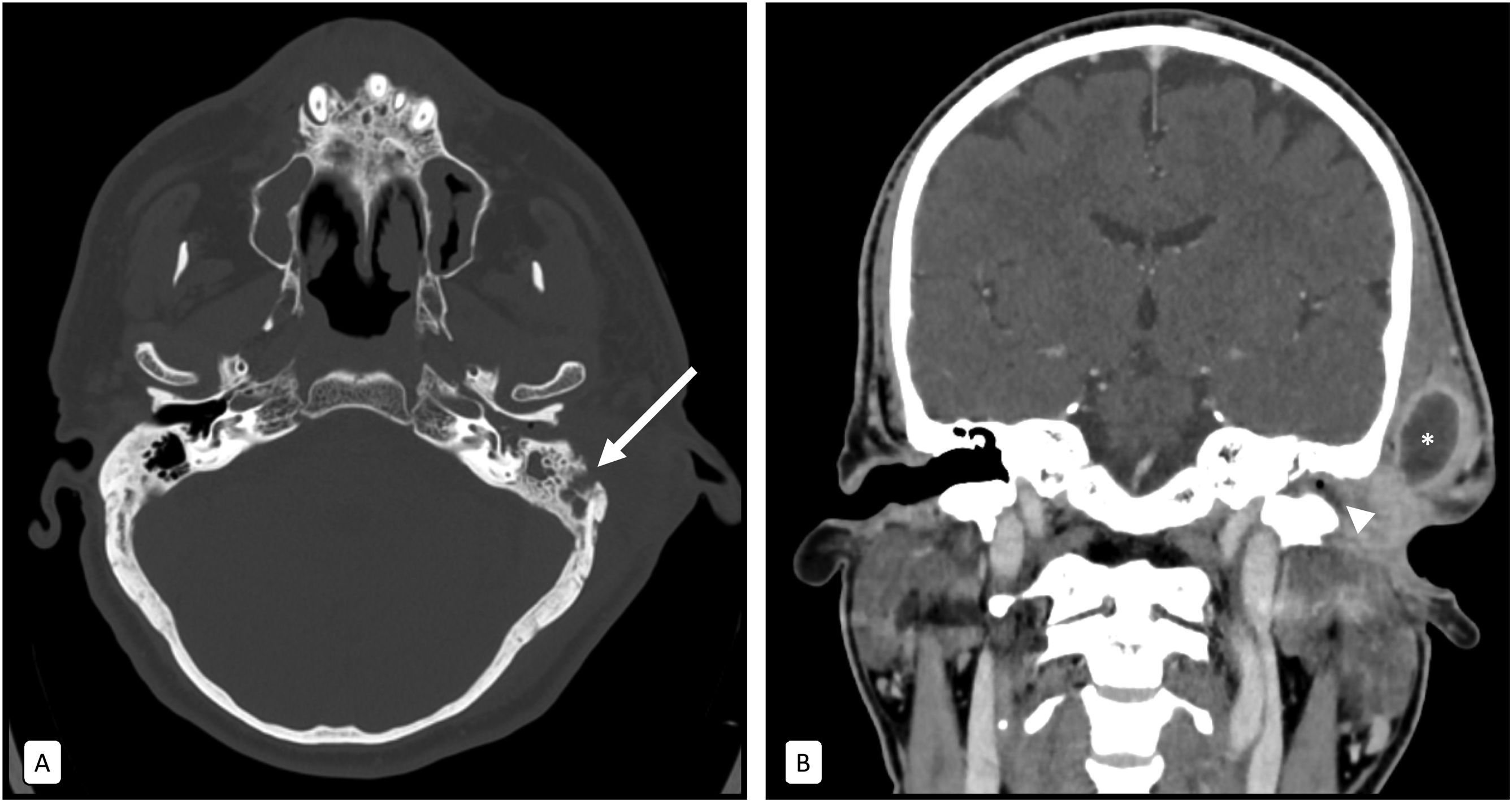

A similar situation applies to acute otomastoidis, and the real radiological work will be to rule out possible associated complications. When it progresses, erosion of the mastoid septa may lead to coalescent mastoiditis. Petrous apicitis in patients with pneumatised petrous apex may extend to the skull base.

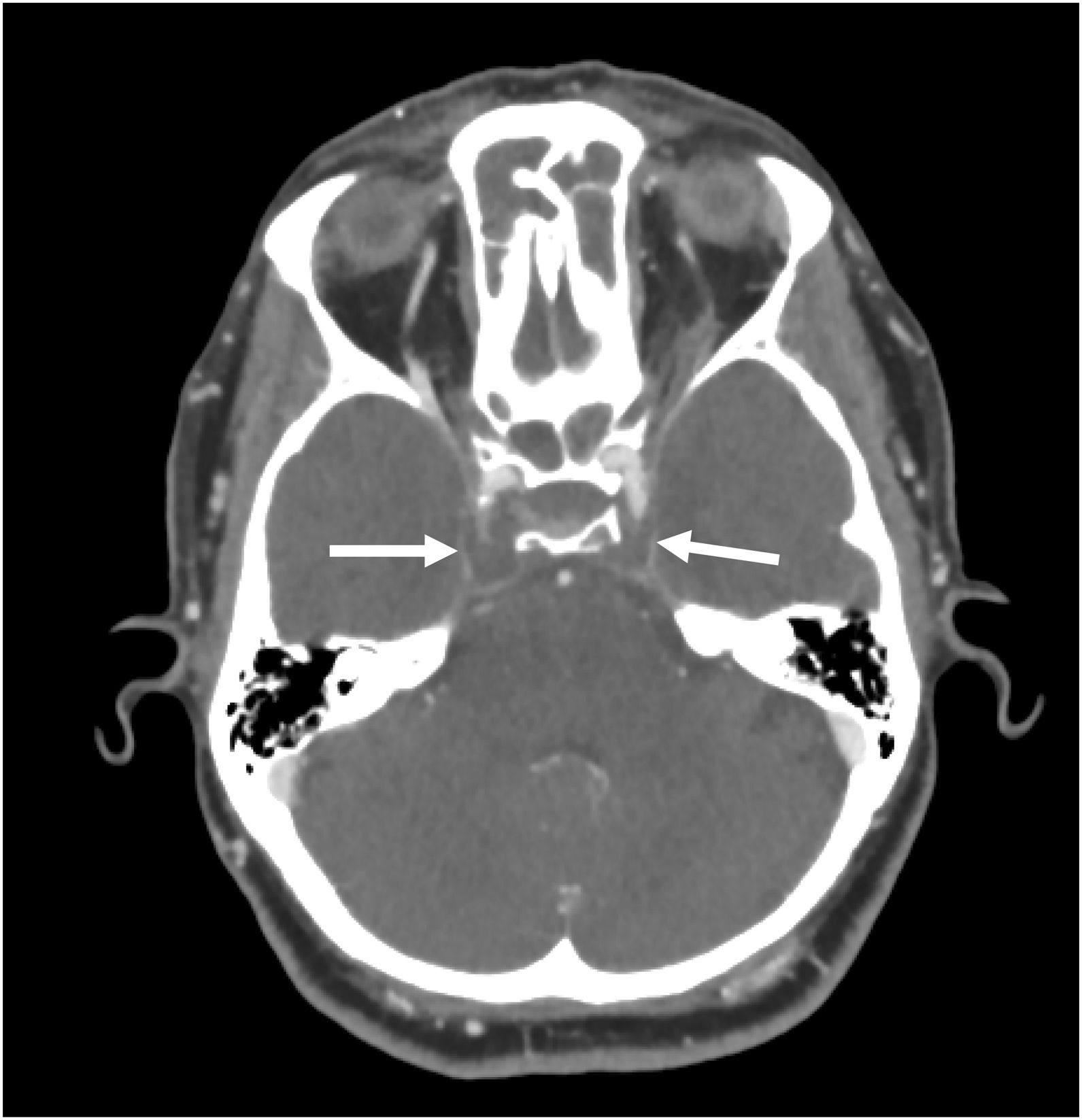

It should be remembered that erosion of the external cortex of the mastoid facilitates the formation of cervical abscesses (Bezold’s abscess) (Fig. 7), and erosion of the internal cortex can be associated with thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus, epidural abscesses and cerebritis2 (Fig. 8).

Erosive otomastoiditis with preauricular abscess. A 58-year-old male with a painful, crackling preauricular tumour. The cross-sectional image with bone window (A) shows occupation of the left mastoid cells by hydro-aerial content with destruction of the external bone cortex (arrow). The coronal image with soft tissue window (B) also shows hydro-aerial content within the external auditory canal (arrowhead) and a collection with an irregular enhanced rim adjacent to the mastoid (asterisk).

Otomastoiditis complicated by signs suggestive of meningitis and cerebritis. A 70-year-old female with decreased level of consciousness and headache. In the axial image with bone window (A), soft tissue attenuation material occupies the left mastoid cells (arrow). The coronal reconstruction (B) of the skull CT scan after contrast administration shows meningeal enhancement in the left tentorium (arrowhead) as a sign suggestive of meningitis. The axial reconstruction (C) shows a hypoattenuating area with a discreetly enhanced border (asterisk) and left temporal cortico-subcortical involvement, which could be related to cerebritis and incipient abscess.

We must follow the carotid and vertebral axes, as well as the included segments of the Willis polygon to detect incidental vascular pathology (aneurysms, dissections, bleeding...). Normally the vascular wall has thin (1–2 mm) well-defined borders and the lumen usually maintains a homogeneous diameter. Cervical arterial inflammation is a rare cause of neck pain in which concentric mural thickening can be seen.9

When assessing venous structures, images of valves and heterogeneous enhancement due to blood-contrast mixing must not be confused with signs of thrombosis. Special attention should be paid to thrombogenic risk factors, hypercoagulable states or in patients with venous catheters.

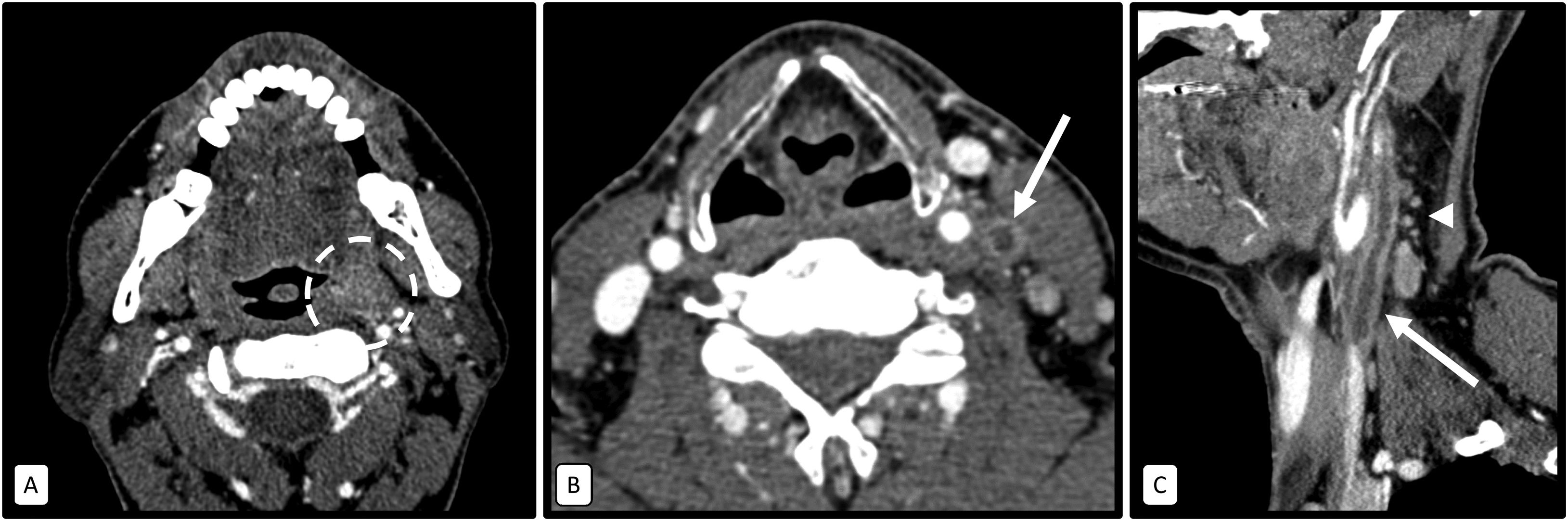

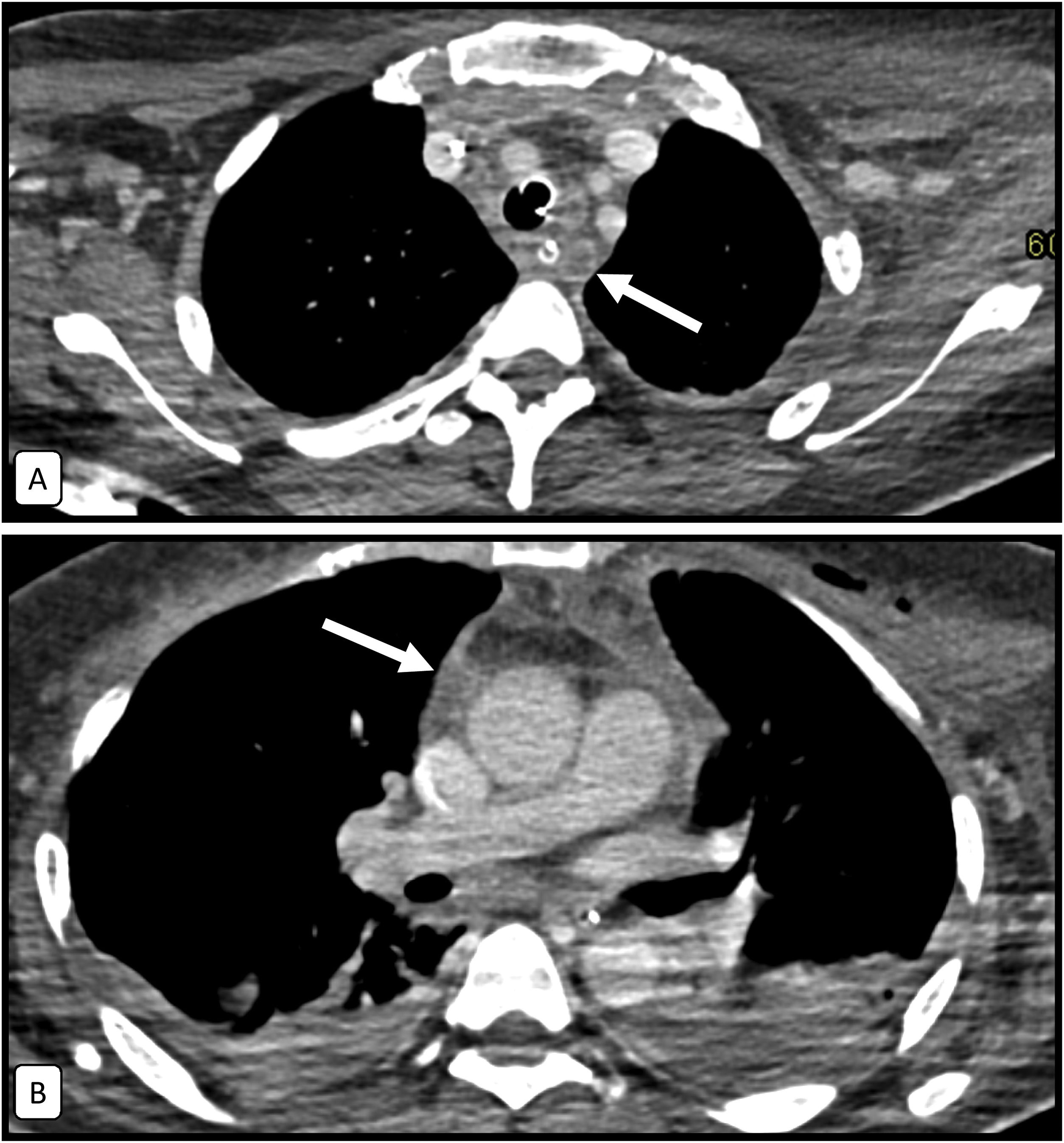

Lemierre’s syndrome (Fig. 9) is septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein secondary to pharyngitis and peritonsillar abscesses. It is often associated with systemic spread with septic pulmonary emboli and high mortality.9

Lemierre’s syndrome. A 55-year-old male with submandibular pain and cervical swelling. The axial image (A) shows a moderate enlargement and enhancement of the left palatine tonsil (circle), with partial collapse of the posterior parapharyngeal fat, related to tonsillitis. The axial (B) and coronal (C) reconstructions show a central repletion defect of the left internal jugular vein (arrows), with concentric parietal thickening. It is associated with trabeculation of the adjacent fat and reactive laterocervical adenopathies (arrowhead). Findings suggestive of septic thrombophlebitis.

Up to 95% of pharyngeal arch anomalies are of the second pharyngeal arch, most commonly located adjacent to the carotid space between the carotid bifurcation and the mandibular angle.10 Various types exist:

- •

Fistula: internal and external connection.

- •

Sinus: external connection only.

- •

Cysts: without internal or external connection, the most common.

It is often found enlarged (goitre) and with heterogeneous nodules, so in the emergency department we will focus on assessing its mass effect on the trachea, oesophagus and vascular structures, as well as the presence of haemorrhagic lesions. Infectious thyroiditis is a rare entity that can develop in the presence of risk factors such as immunodeficiencies or anomalies of the fourth pharyngeal arch (Fig. 10).

Acute infectious thyroiditis. A 29-year-old male with a history of pharyngeal arch cyst and clinical manifestations of cervical swelling. The axial (A) and coronal (B) planes of the contrast-enhanced CT show a hypointese area of irregular shape in the left thyroid lobe (arrows), as well as a loss of the fat plane of separation with the prethyroid musculature.

Parotitis is more common in the elderly due to bacterial ascension from the oral cavity, while submaxillitis occurs more due to obstructive sialolithiasis (Fig. 11). If it is bilateral, viral involvement or autoimmune syndromes should be considered. Ductal dilatation can sometimes be observed, and the presence of lithiasis in the ducts of Stenson and Wharton must be ruled out.2

Submaxillitis of lithiasic aetiology. An 88-year-old female with pain in the submandibular region that is increased after meals. The soft tissue window (A) shows a significant enlargement of the right submandibular gland (asterisk) with trabeculation of the adjacent fat. In the bone window (B) a millimetric calcium-density structure is identified in the theoretical path of Wharton’s duct, which is compatible with a sialolith (arrow).

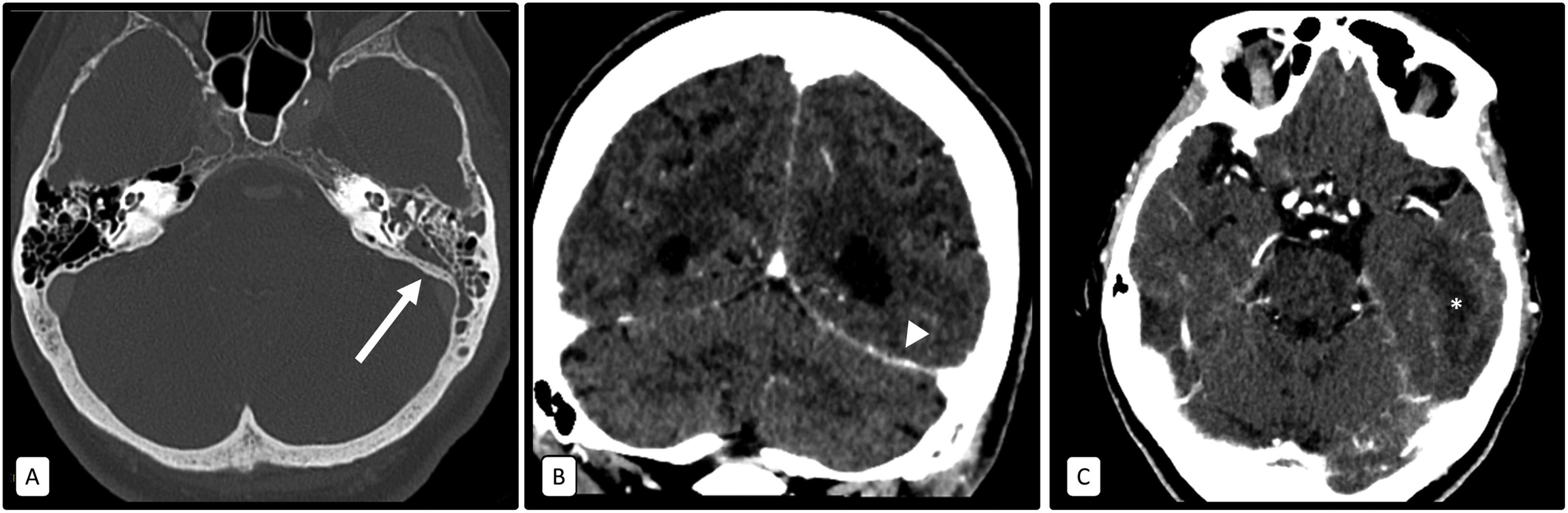

It is vital to assess the intracranial extension of infectious processes (especially after sinusitis/mastoiditis), which can be complicated by the formation of epidural and cerebral abscesses, subdural empyemas, meningitis and cerebritis (Fig. 8).11

OrbitsOrbital cellulitis is more common as an extension of ethmoidal sinusitis and can be complicated by the formation of orbital/subperiosteal abscesses (Fig. 12) and thrombosis of the cavernous sinus via the superior ophthalmic vein. Acute manifestations of thyroid-associated orbitopathy may mimic this entity.12

Orbital cellulitis with periosteal abscess as a complication of ethmoid sinusitis. A 4-year-old boy with proptosis and eye pain following an upper respiratory tract infection. The bone window (A) shows a hydroaerial occupation of the ethmoidal cells and slight erosion of the lamina papyracea of the left orbit (arrow). The soft tissue window (B) shows trabeculation of the orbital fat of the pre-septal and post-septal spaces, identifying a hypodense collection with a hyperintense border and laminar morphology adjacent to the bony cortex (asterisk) and a left proptosis (measured as a distance >23 mm between the interzygomatic line and the anterior border of the eyeball) (dashed line and arrow).

It should be remembered that orbital compartment syndrome can occur due to orbital cellulitis and not only after trauma. We will observe a marked proptosis (distance between the interzygomatic line and the anterior ocular surface >23 mm), with posterior ocular deformity in a “guitar pick” shape and significant stretching of the optic nerve.12

Spinal cordAlthough magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the reference test for its assessment, some pathologies may simulate extra-spinal entities, so it should be taken into account when reading CTs in the ED.

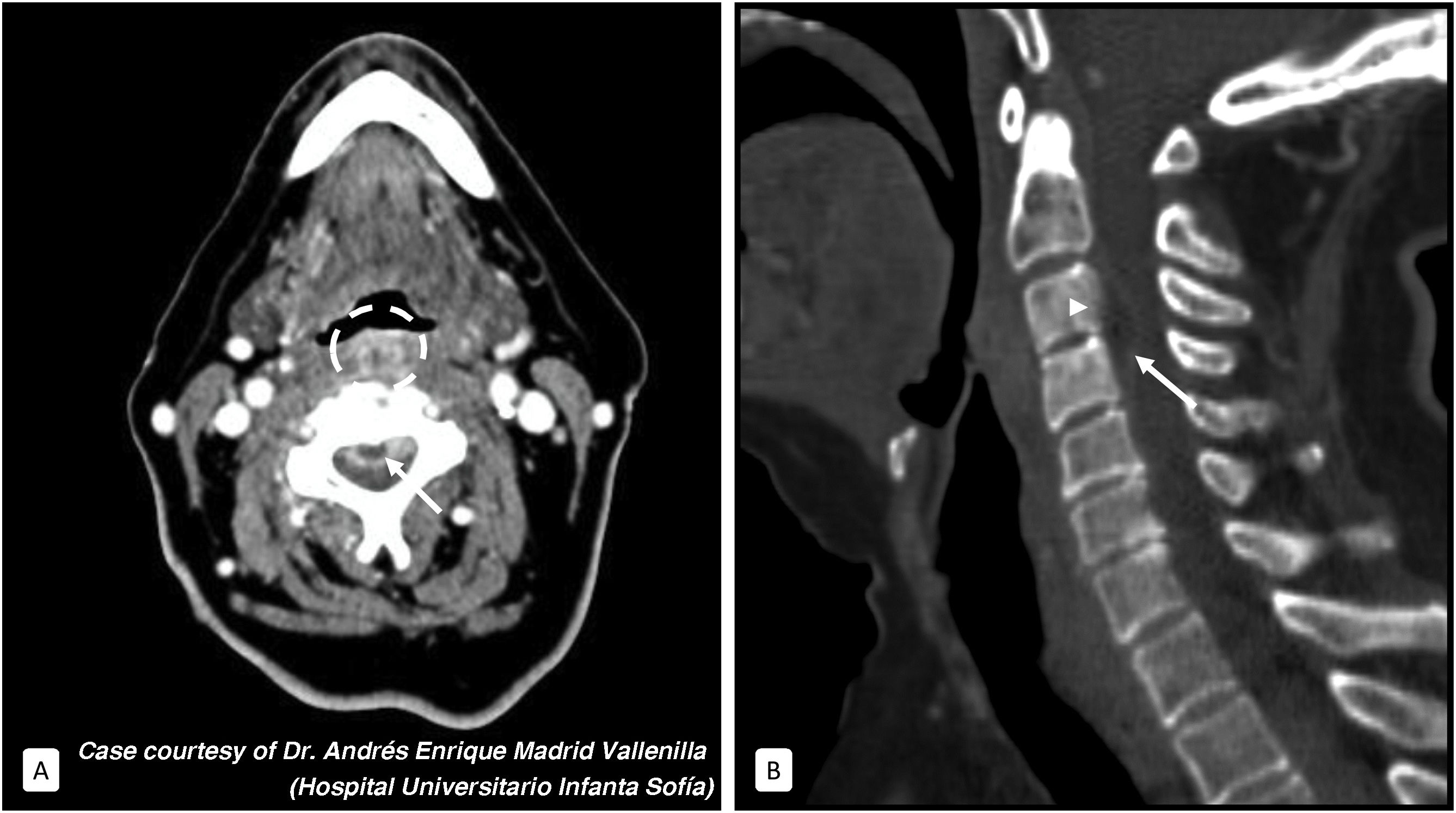

Bacterial discitis is often accompanied by vertebral osteomyelitis and is caused by haematogenous, direct retropharyngeal/paraspinal and post-instrumentation spread. Loss of disc space height, erosion of the adjacent vertebral plates and trabeculation of the paraspinal fat are observed. It may be associated with retropharyngeal oedema and epidural abscesses/phlegmon2 (Fig. 13). It is necessary to specify whether there is stenosis of the spinal canal or anomalies of vertebral alignment.

Retropharyngeal abscess complicated by cervical spondylodiscitis and epidural abscess. A 73-year-old female with severe cervical pain for weeks following an episode of fish bone impaction. The axial soft tissue window image (A) shows a heterogeneous area of soft tissue enhancement with hypodense areas delimited by peripheral enhancement in the retropharyngeal space (circle), suggestive of phlegmonous changes and abscess. A hypodense collection is also identified in the anterior epidural space, with an air microbubble inside and peripheral enhancement suggestive of abscess (arrow). The sagittal image with bone window (B) shows a generalised increase in the density of the adjacent vertebral bodies (C3 and C4), as well as a slight irregularity of the bony cortex (arrowhead).

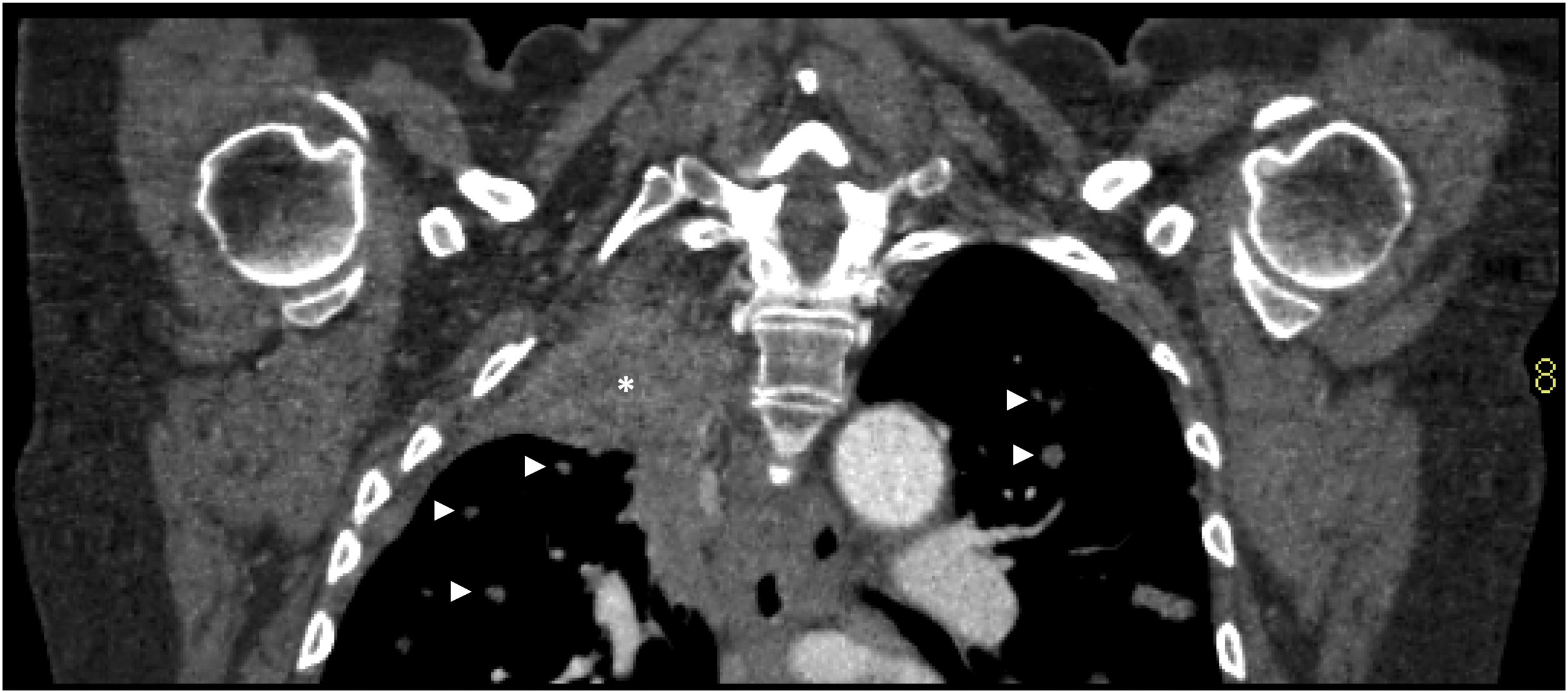

The upper lobe parenchyma, pleural surface and part of the vessels and upper airway are usually partially included in the study. In many cases, the cause or complications of cervical pathology, such as septic emboli associated with Lemierre’s syndrome, can be identified.

Incidental findings are vital for the correct management and prognosis of the patient (pneumonias, nodules, masses, pulmonary oedema, COVID-19...) (Fig. 14). For example, in the case of identifying metastases, it will help us to classify a cervical tumour/adenopathy as neoplastic rather than inflammatory.

Pancoast tumour as an incidental finding on a neck CT. A 69-year-old male underwent a cervical CT scan to study adenopathies. Coronal reconstruction showing a mass in the right lung apex extensively contacting the pleural surface (asterisk) and bilateral pulmonary nodules suspicious for metastases (arrowheads).

The most common causes of acute mediastinitis (Fig. 15) are oesophageal perforation, extension of a head and neck infection, and as a secondary complication of cardiothoracic surgery.13Descending necrotising mediastinitis (Fig. 5) is a rare and very serious complication of oropharyngeal or dental infections.14

It should be remembered that the longitudinal orientation of the deep cervical fascia allows propagation routes through the danger space from the base of the skull to the diaphragm.9

Structured radiology report and summary of findingsA structured radiology report is recommended especially in the context of emergency care, which requires more immediate attention, and especially for less common studies in complex anatomical regions such as the neck, where it is helpful to have a complete list of the elements to be evaluated.

Once the characteristics of the protocol have been mentioned, it is advisable to describe, for each item of the checklist shown, a concise description of the pathological findings that we consider noteworthy. Finally, we must summarise and relate these to each other, to adjacent elements and to the underlying pathophysiological process in order to conclude a coherent diagnosis.

ConclusionsCervical CT with intravenous contrast is the test of choice in non-traumatic cervical emergencies. Due to the complexity of the neck’s anatomy, it should be assessed systematically following the seven elements described above. In addition to identifying the pathology, the use of this checklist allows for a structured and concise report.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the study as a whole: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 2.

Study conception: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 3.

Study design: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 4.

Data collection: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 6.

Statistical processing: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 7.

Bibliographic search: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 8.

Drafting of the paper: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: JMCG, CUC, PGR, SOV, MMG and GGM.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.