MRI is the cornerstone in the evaluation of brain metastases. The clinical challenges lie in discriminating metastases from mimickers such as infections or primary tumors and in evaluating the response to treatment. The latter sometimes leads to growth, which must be framed as pseudo-progression or radionecrosis, both inflammatory phenomena attributable to treatment, or be considered as recurrence. To meet these needs, imaging techniques are the subject of constant research. However, an exponential growth after radiotherapy must be interpreted with caution, even in the presence of results suspicious of tumor progression by advanced techniques, because it may be due to inflammatory changes. The aim of this paper is to familiarize the reader with inflammatory phenomena of brain metastases treated with radiotherapy and to describe two related radiological signs: "the inflammatory cloud" and "incomplete ring enhancement", in order to adopt a conservative management with close follow-up.

La resonancia magnética es la piedra angular en la evaluación de las metástasis cerebrales. Los retos clínicos residen en discriminar las metástasis de imitadores como infecciones o tumores primarios y en evaluar la respuesta al tratamiento. Éste, en ocasiones, condiciona un crecimiento, que debe encuadrarse como una pseudoprogresión o una radionecrosis, ambos fenómenos inflamatorios atribuibles al tratamiento; o bien considerarse como una recurrencia. Para responder a estas necesidades, las técnicas de imagen son objeto de constantes investigaciones. No obstante, un crecimiento exponencial tras radioterapia, debe interpretarse con cautela, incluso ante resultados sospechosos de progresión por técnicas avanzadas, ya que puede tratarse de cambios inflamatorios. El objetivo de este trabajo es familiarizar al lector con los fenómenos inflamatorios de las metástasis cerebrales tratadas con radioterapia y describir dos signos radiológicos relacionados: “la nube inflamatoria” y el “realce en anillo incompleto”, con el fin de adoptar un manejo conservador con seguimiento estrecho.

Brain metastases are the most common intracranial tumours among adults and are associated with poor survival. They are found in 15%–40% of cancer patients.1

The distribution of brain metastases depends on blood flow, and they usually reach the brain through the arteries. Consequently, they are mostly located in the middle cerebral artery territory, in distal vascular regions and areas where there is an arterial calibre change, such as the grey-white matter junction.2 A venous spread of metastatic disease is typical of pelvic (prostate and uterine) and gastrointestinal primary tumours. It spreads via the Batson venous plexus to the inferior petrosal sinus.3 This explains the predisposition to infratentorial involvement.

The first-choice imaging test for the evaluation of brain metastases is MRI.4 CT scans are requested in emergency situations to assess patients with neurological deficits.5

Metastases are not usually haemorrhagic, although choriocarcinomas, melanomas, and metastases originating in the thyroid or kidney are more frequently associated with haemorrhage. Lung and breast metastases bleed only occasionally; however, they are responsible for the majority of metastatic haemorrhages since they are the most prevalent primary tumours.6

Metastases can be parenchymal or extra-axial.7 Leptomeningeal (LM) involvement occurs through the haematogenous spread of malignant cells, whereas meningeal carcinomatosis or meningeal seeding, typical of breast or lung tumours, spreads via the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The downward flow of the cancer cells explains the tumour predisposition for the posterior fossa. Some authors do not differentiate between the two situations.7 However, survival in the first scenario can extend to years in patients who respond well to radiotherapy (RT) treatment, or in patients treated with targeted therapies called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for mutations in receptors such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) receptor tyrosine kinase. Conversely, prognosis for carcinomatosis is poor.8

The aim of this article is to summarise the radiological features of brain metastases. Growth after RT should not always be interpreted as tumour recurrence, as it may be related to inflammatory phenomena. It is important to differentiate tumour growth from inflammation in order to avoid unnecessary surgery or repeat radiation. This article describes the characteristics of these inflammatory phenomena and highlights two radiological signs, the ‘inflammatory cloud’ and the ‘incomplete ring enhancement’, which have been associated with pseudoprogression and radiation necrosis.

Treatment of brain metastasesRadiologists must be familiar with treatments for brain metastases in order to adequately assess response. Treatment can be local via RT or surgery, or even systemic, in cases where certain mutations allow for targeted therapy.1 According to the European Society for Medical Oncology, the choice depends on the location, size and number of lesions, as well as the status of the extracranial disease, the general condition of the patient and the histological type, given that melanoma and renal cancer are, by way of example, more resistant to radiation.9,10 Surgery is usually the first-line treatment for patients with unknown histology, good general health, and a single, accessible lesion or metastasis with a mass effect that causes significant symptoms. Radiosurgery can be considered for patients with one to multiple metastases, administered in a single session to lesions with a diameter <3 cm and fractionated when the volume is greater.11

Whole brain radiotherapy approaches are only used on patients with multiple metastases and for palliative purposes, in contrast with intracranial stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), which is more radical.

SRS is a non-invasive technique based on a system that converges radiation beams to deliver a high dose of radiation with great precision to a small volume with a rapid dose fall-off. This gives it high biological effectiveness with high rates of local control of up to 90% in the first year.12

Radiosurgery was traditionally reserved for patients with ≤2 brain metastases,11 although international guidelines increasingly recommend it for the treatment of patients with up to 10 lesions, maximising local control and avoiding the long-term effects of whole-brain radiotherapy.13 Fractionated SRS is similar to single-dose SRS in that it is performed under stereotactic conditions, but the total dose is fractionated over several sessions. This improves the therapeutic index, the rate of repair for healthy tissue, and thus the level of tolerance when the lesion is large or in close proximity to healthy organs that are sensitive to radiation, such as the optic pathway. Some studies have also demonstrated the efficacy and safety of hypofractionated radiosurgery schedules based on five fractions of 6–7 Gy or 10 fractions of 4 Gy14–16 in patients with brain metastases larger than 3 cm. Hypofractionation is also applied when using radiation to treat a site that has previously undergone surgery.16

Assessment of brain metastasis responseMRI is the technique of choice for assessing brain metastasis response to therapy.4 CT is useful in the initial assessment and in the perioperative setting.17 In general, CT scans are requested in emergency situations, such as the presence of neurological deficits, in order to rule out other complications.5 Treatment planning, however, is performed by MRI whenever available as it enables the detection of millimetric metastases which would go undetected by CT, and whose detection is likely to change the choice of treatment.5 The United States National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with brain metastases receive follow up every two to three months during the first one to two years, and then every four to six months indefinitely.18 Whole neuraxis MRI should be performed if there are signs or symptoms suggestive of intraspinal involvement, and some authors argue for its use in cases of cerebral LM involvement given that up to a third of patients have imaging findings that affect the treatment of LM involvement.19 Furthermore, in a review of 72 patients with intraspinal involvement that was secondary to primary tumours originating outside the central nervous system, only half presented with concurrent intracranial involvement.20

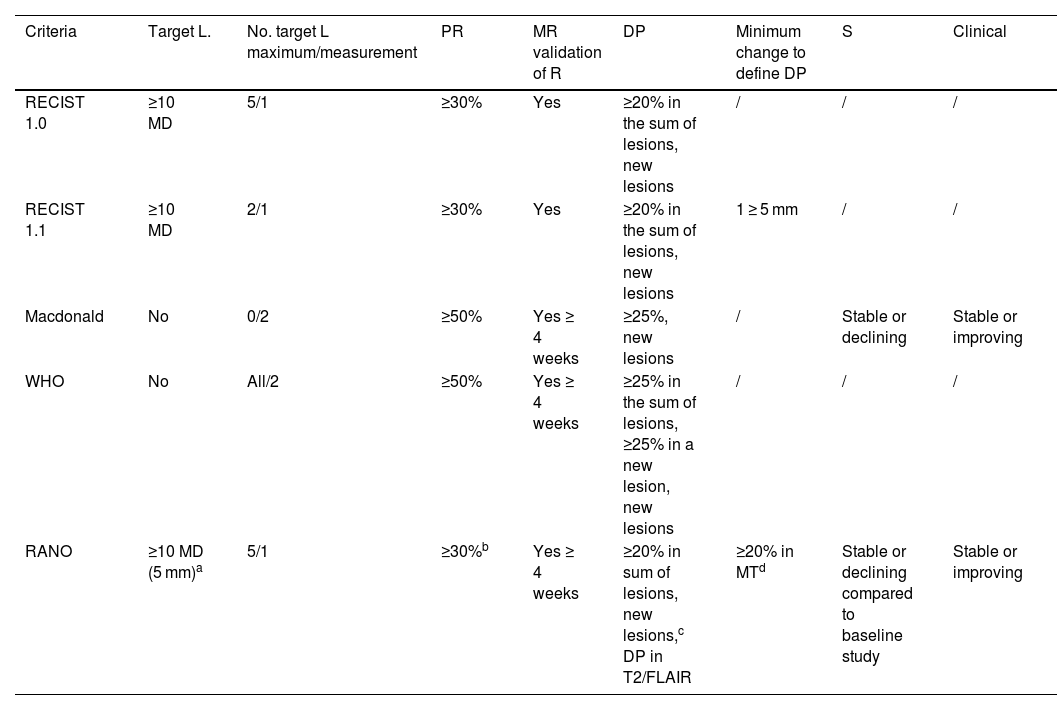

Response assessment scalesOver the years, different scales with heterogeneous radiological criteria have emerged to assess the response of brain metastases. The Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) working group21,22 sought to unify them by proposing new criteria for the assessment of brain metastases (RANO-BM) (Table 1).21 These criteria define a partial response as a 30% reduction in diameter which must be maintained for four weeks. Progression is determined by 20% growth. In addition, the immunotherapy response assessment for neuro-oncology (iRANO) criteria specifically suggest waiting until the sixth month after the start of treatment before determining progression if the patient is clinically stable.21,23 The RANO criteria arose from the need to assess the response in patients included in clinical trials and treated in most cases with systemic therapy.21

Characteristics of response assessment criteria in neuro-oncology trials.

| Criteria | Target L. | No. target L maximum/measurement | PR | MR validation of R | DP | Minimum change to define DP | S | Clinical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECIST 1.0 | ≥10 MD | 5/1 | ≥30% | Yes | ≥20% in the sum of lesions, new lesions | / | / | / |

| RECIST 1.1 | ≥10 MD | 2/1 | ≥30% | Yes | ≥20% in the sum of lesions, new lesions | 1 ≥ 5 mm | / | / |

| Macdonald | No | 0/2 | ≥50% | Yes ≥ 4 weeks | ≥25%, new lesions | / | Stable or declining | Stable or improving |

| WHO | No | All/2 | ≥50% | Yes ≥ 4 weeks | ≥25% in the sum of lesions, ≥25% in a new lesion, new lesions | / | / | / |

| RANO | ≥10 MD (5 mm)a | 5/1 | ≥30%b | Yes ≥ 4 weeks | ≥20% in sum of lesions, new lesions,c DP in T2/FLAIR | ≥20% in MTd | Stable or declining compared to baseline study | Stable or improving |

DP: disease progression; L: lesion; MD: maximum diameter; Measurement: uni- or bidimensional; PR: partial response; R: response; RANO: response assessment in neuro-oncology; RECIST: response evaluation criteria in solid tumours; S: steroids; /: not included, 0: not specified.

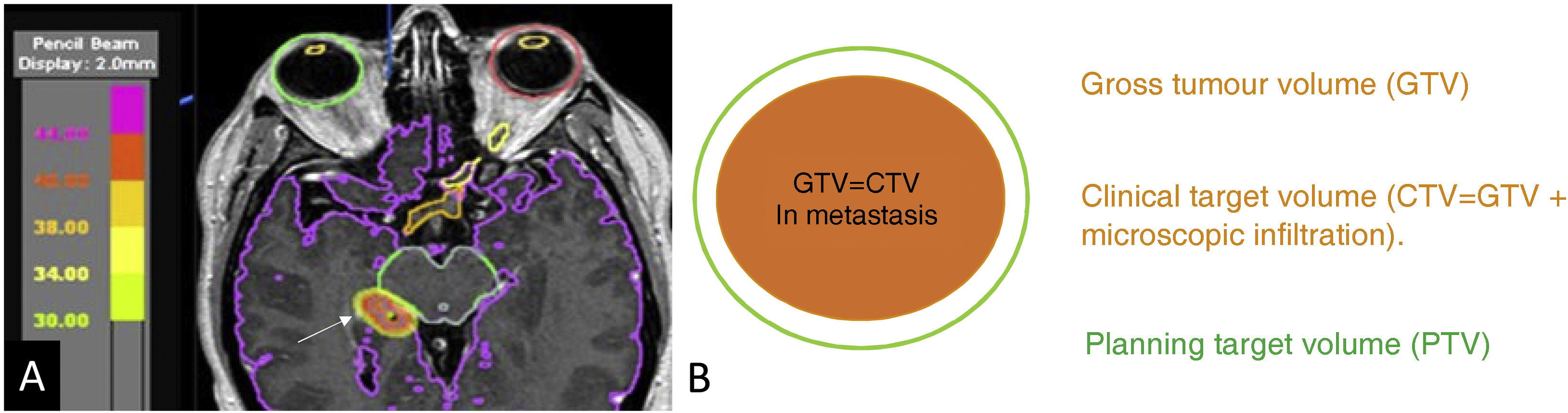

The gross tumour volume (GTV) can be measured on MRI.24 In well-delineated metastases, the GTV is equal to the clinical target volume (CTV), which includes microscopic spread around the tumour. The planning target volume (PTV) adds a safety margin around the CTV to overcome both intrinsic and extrinsic uncertainties when performing the technique due to possible organ movement, the positioning of the patient or technical inaccuracies.24 In single-dose radiosurgery of brain metastases, the PTV is generally equal to the GTV and CTV. In fractionated treatments, a margin of 1 mm is usually added to the CTV to generate the PTV (Fig. 1).24 Increasing this margin has been shown to lead to an increased risk of radiation necrosis.25

Radiotherapy planning image for a metastasis in the right hippocampus (coloured orange and marked with arrow) (A). Organs at risk are delineated including the eyeballs, chiasm, optic nerves and midbrain. The gross tumour volume (GTV) shown in orange is the volume of the metastasis that we can delineate on the MRI. In metastases, the GTV is equal to the clinical target volume (CTV), as there is no peritumoural infiltration. The planning target volume (PTV) may add a margin of 0 mm for radiosurgery or a minimum of 1 mm (green halo) for fractionated treatments.

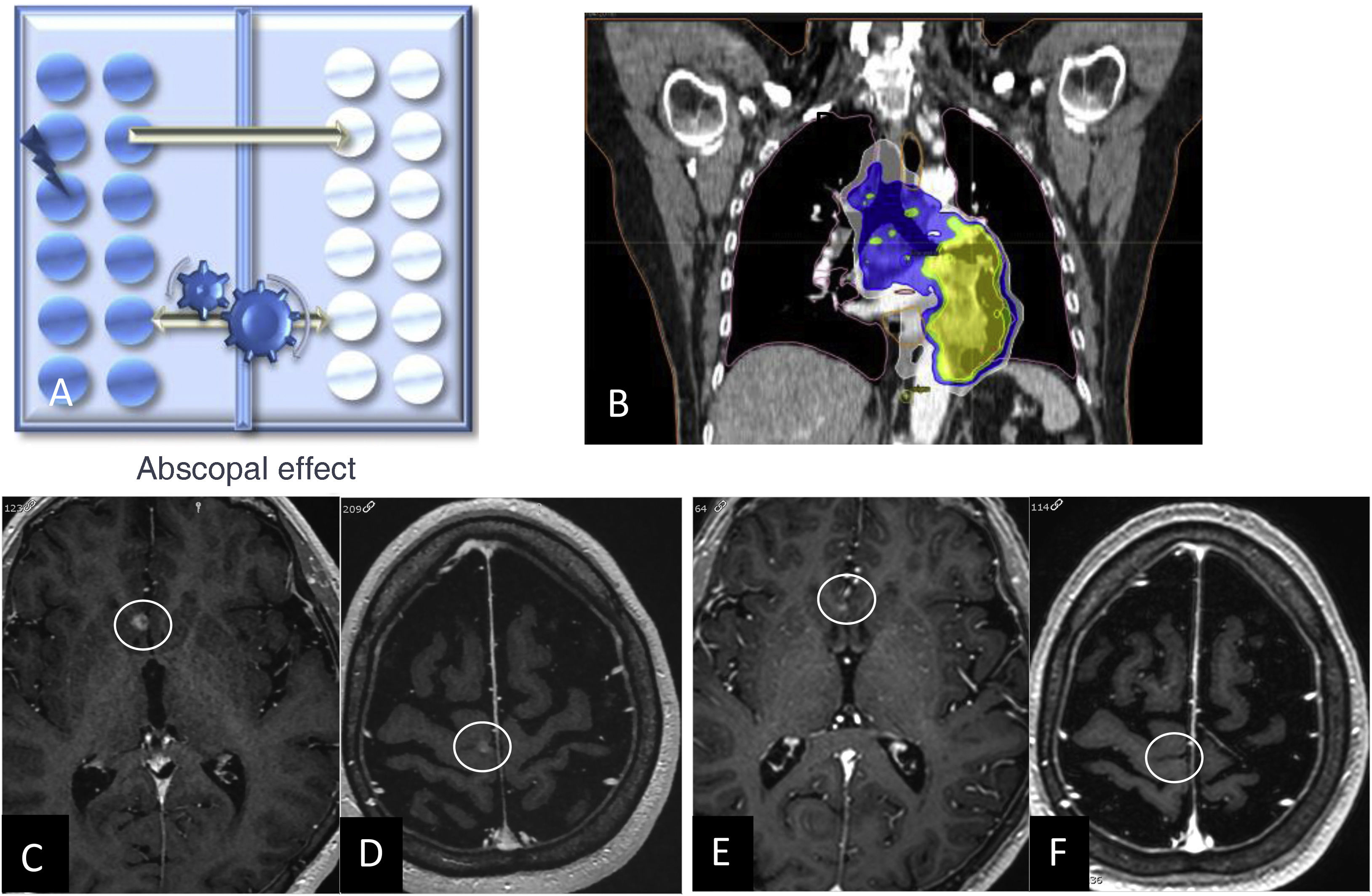

When assessing responses after RT treatment, two phenomena are of interest: the abscopal effect and the bystander effect. The abscopal effect, coined by Robin Mole in 1953, is a radiobiological event occurring outside the irradiated volume in the same individual, i.e., it refers to tumour regression of distant metastases away from the local treatment area in the absence of other treatment (Fig. 2).26 The bystander effect describes changes to non-irradiated cells as a result of signals received from neighbouring irradiated cells (Fig. 3).27,28

Diagram depicting the abscopal effect, where there is a metastatic cell response (in white) when cells in another organ are irradiated (shown in blue) (A). Chest CT coronal image for lung cancer radiotherapy planning (B). Contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted images prior to lung irradiation (C, D) and two months after treatment (E, F) showing a response in both brain metastases in the absence of other treatments.

Diagram depicting the bystander effect (A), where there is a metastatic cell response (in light blue) when neighbouring cells are irradiated (shown in blue). Head CT image showing treatment planning with radiotherapy (B and C). Contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted images prior to fractionated radiotherapy (D) and two months after treatment (E), showing a response in the radiated areas of the brain with metastasis (arrows) and the right thalamic lesion (circle) not included in the irradiation field of any of the lesions, and in the absence of any other targeted treatment. Note the appearance of a new left frontal metastasis (E) (arrowhead).

The growth of a metastasis after irradiation can be caused by treatment-related changes, including both pseudoprogression and radiation necrosis. While some authors group them together as a single entity, they constitute two distinct developments.29

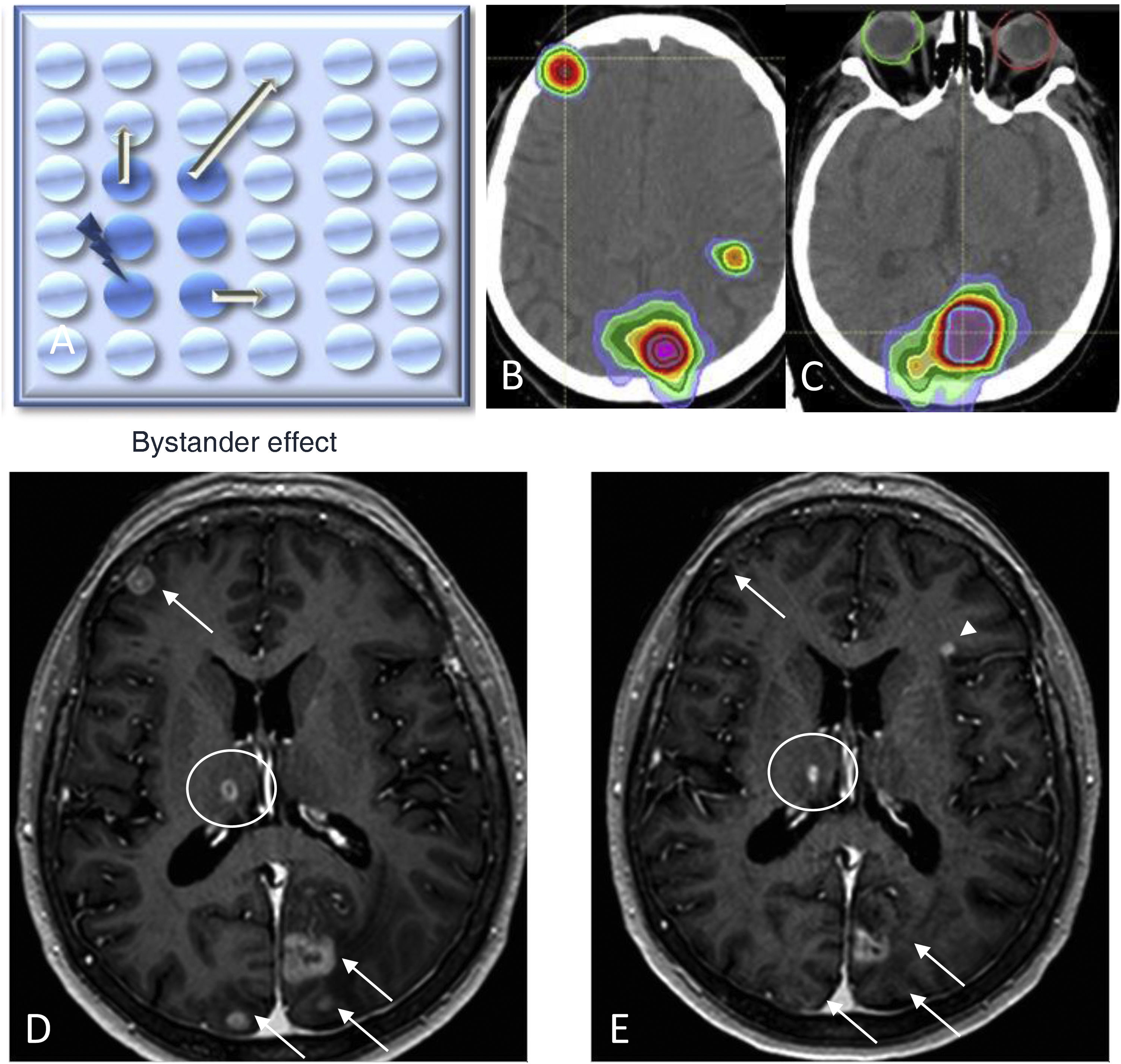

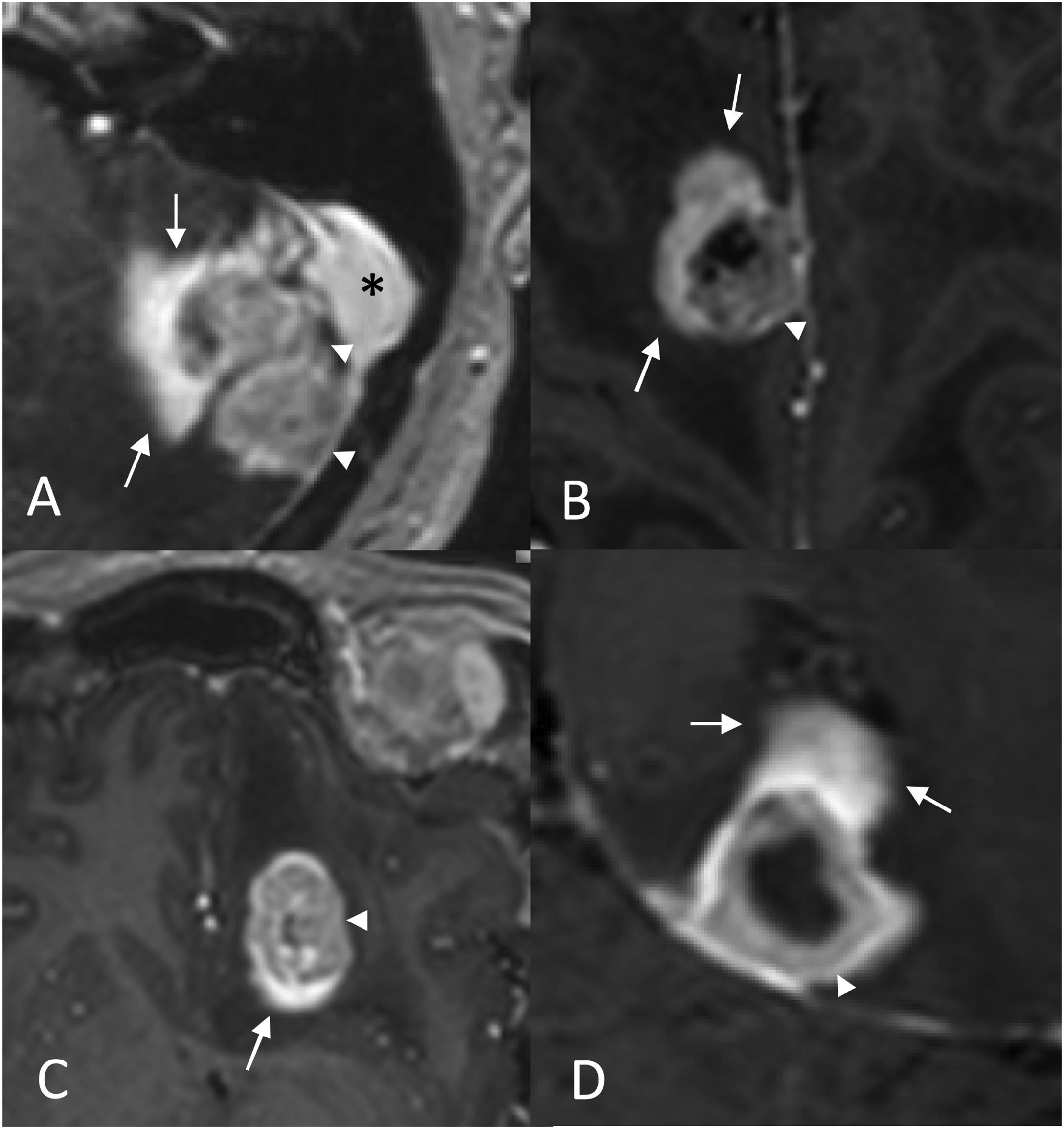

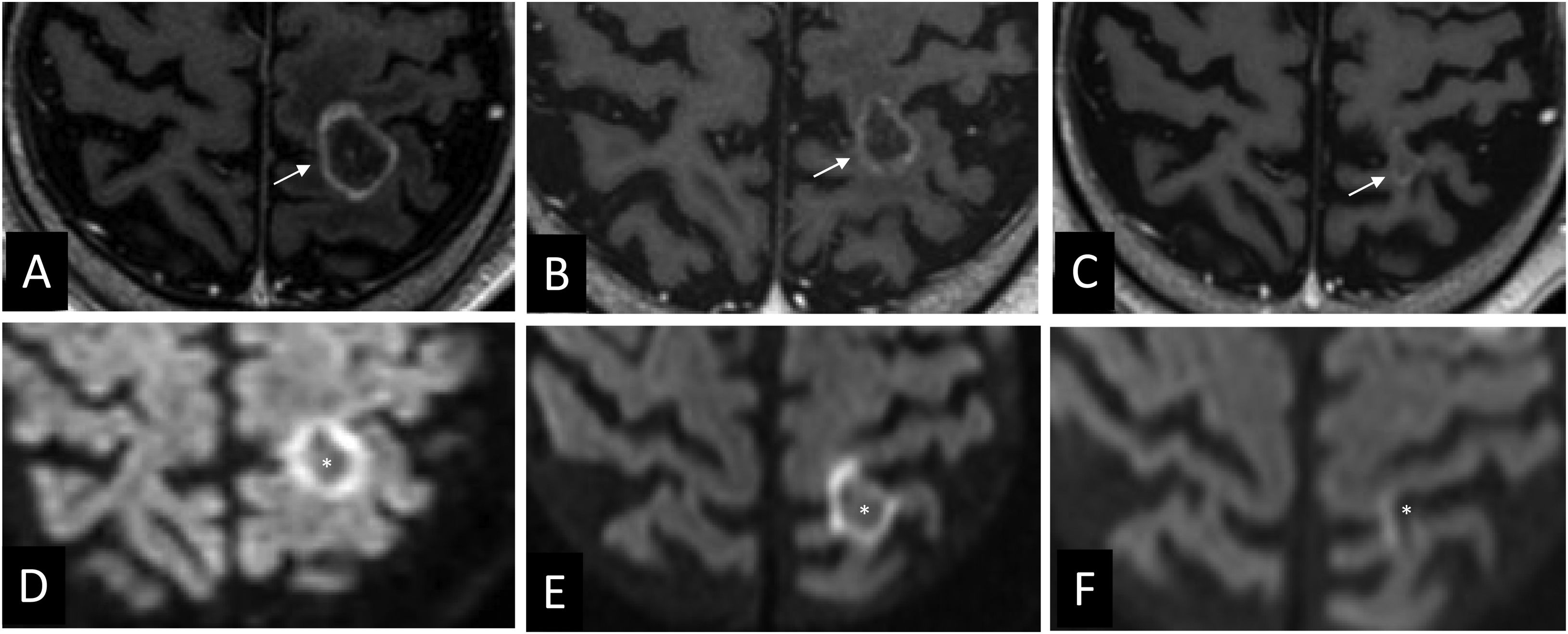

(a) Pseudoprogression and the ‘inflammatory cloud’ signPseudoprogression describes a transient growth caused by inflammatory changes induced by RT or systemic treatment (Fig. 4).21,29 This growth appears early, typically occurring in the first three months after RT and usually before the sixth month, and occurs in up to 10% of cases.29 Its significance is demonstrated by the fact it is responsible for two thirds of growth after RT.30 It has been associated with good local control and immune response, explaining its higher frequency in patients receiving immunotherapy or in young patients.31–33 This phenomenon may be suspected in cases where the ‘inflammatory cloud’ radiological sign is present.31 This sign describes enhancement around the metastasis which is more intense than the tumour tissue itself and has blurred, ill-defined margins, resembling a cloud (Fig. 5).31 It represents focal uptake as it does not typically surround the entire metastasis and may correspond to an inflammatory infiltrate.31 In the context of pseudoprogression, one working group presented an image similar to that described without describing the inflammatory cloud itself,32 and others described enhancement that may not have had a tumoural association.32,34 The ‘inflammatory cloud’ sign appears both in treatment-naïve metastases and in treated lesions. As with pseudoprogression, the ‘inflammatory cloud’ is associated with good local control (Fig. 6).31 The fact that this sign is almost exclusive to melanoma, lung and breast metastases, which are precisely those that are typically associated with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), suggests that the two phenomena may be related.31,35 The RANO group has also suggested that pseudoprogression may be linked to immune infiltrates in the context of immunotherapy treatment.21

Pseudoprogression. Ovarian cancer patient with brain metastasis treated with radiosurgery. Contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted cross-sectional images: pre-treatment (A), at three months (B), at six months (C) and at nine months (D). A transient growth is shown as the lesion responds progressively at six and nine months. The ‘inflammatory cloud’ sign is visible in the three-month image (B) in the form of intense peripheral enhancement (arrows) surrounding the tumour tissue (arrowhead) with extensive associated vasogenic oedema (*). Note how this tumour tissue enhances less intensely than the ‘cloud’ (arrows) and how it has decreased in size with respect to the previous one, although the overall volume of enhancing tissue is greater in the three-month MRI. The MRI scan performed four years later (not shown) shows no recurrence in this area.

‘Inflammatory cloud’ sign. Contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted images show an area of intense, focal and peripheral enhancement that could correspond to an inflammatory infiltrate (arrows) around the tissue interpreted as tumour tissue (arrowhead). The blurred margins give it a cloud-like appearance. In Figure A, the metastasis is located in close relation to the sigmoid sinus (*).

Partial response associated to the ‘inflammatory cloud’ sign. Case 1: Lung cancer patient. Contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted cross-sectional images: pre-treatment (A), and at three months after radiotherapy treatment (B), which show a reduction in the size of the tumour tissue (arrowhead) at the same time that there is a diffuse focal enhancement similar to a ‘cloud’ (arrows in B). Case 2: Breast cancer patient. Contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted cross-sectional images at six months after treatment (C), which show the ‘inflammatory cloud’ sign (arrows). Image D shows a partial response in the cluster of LM metastases (arrowheads).

Radiation necrosis is a complication of RT treatment that has been reported in between 3% and 24% of cases depending on the study series, due to vascular and glial damage.36,37 Histologically, it is an area of coagulative necrosis with fibroblastic proliferation surrounded by a robust infiltrate of inflammatory cells (haemosiderin-laden lymphocytes and macrophages). This marginal reactive zone is circumscribed by an area of gliosis and demyelination.38,39,51 Radiation necroses may contain some tumour cells.39–41 The percentage is variable and possibly depends on the time of evolution.42,43 It seems reasonable to think that the structural damage, and in particular the vascular compromise RT produces, impacts on the microenvironment required for tumour cell proliferation, thus favouring cell death and regression, making it likely that the tumoural percentage of the radiation necrosis will progressively reduce. This would explain the absence of recurrences in areas of radiation necrosis over time.31

Radiation necrosis rarely occurs within six months of or over three years following the end of RT treatment. Eighty-five per cent of cases appear within the first two years; however, there have been cases reported up to 20 years after treatment.44

Risk factors associated with the development of radiation necrosis include the type of primary tumour (renal cancer, lung adenocarcinoma and HER-2 breast cancer), some genetic alterations such as ALK translocations and BRAF37 mutations,37 the addition of systemic treatments (targeted therapies or immunotherapy), the radiation dose and tumour volume, as well as the volume of irradiated healthy tissue receiving a single-dose of ≥10–12 Gy. Sneed et al.45 carried out a retrospective study evaluating a total of 2,200 brain metastases treated with radiosurgery. They found that the risk of symptomatic side effects was 3% after single radiosurgery, 4% after whole brain RT followed by radiosurgery, 8% after whole brain RT combined with radiosurgery, and 20% after two radiosurgeries on the same lesion. Therefore, when metastatic lesions are large, fractionated treatment minimises the risk of radiation necrosis.24 Knowledge of these data allows for a more accurate interpretation of the findings. Thus, the active involvement of radiation oncologists results in more accurate response assessment, which is also enriched by multidisciplinary committees discussing the cases.

Suspicion should be raised whenever there is rapid, exponential growth accompanied by extensive vasogenic oedema.31,46–48 The lesion typically increases in size progressively over six months, eventually slowing for up to 15 months before stabilising or decreasing in size.47 They are most frequently located in the frontal lobes, followed by the area around the ventricles and the corpus callosum.49 In contrast, the resistance of the brainstem to radiation makes it an unusual location for radiation necrosis.49 When multifocal, radiation necrosis is suspected when findings are on both sides of anatomical boundaries such as the brain sickle or the tentorium. In other words, radiation necrosis is suspected when necrotic enhancing lesions are detected on both sides of these structures with no clear continuity between them.31

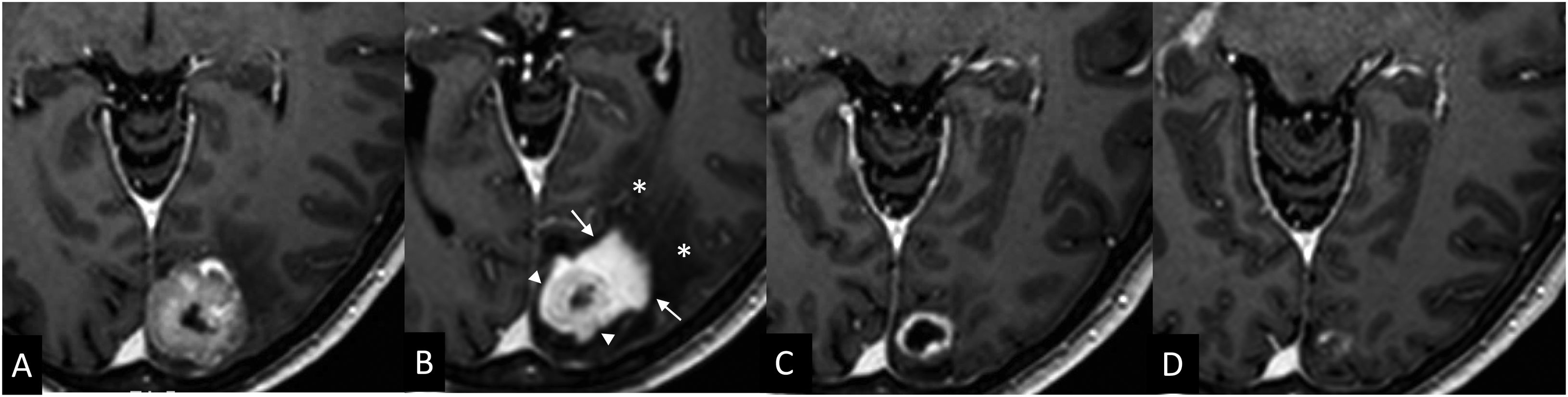

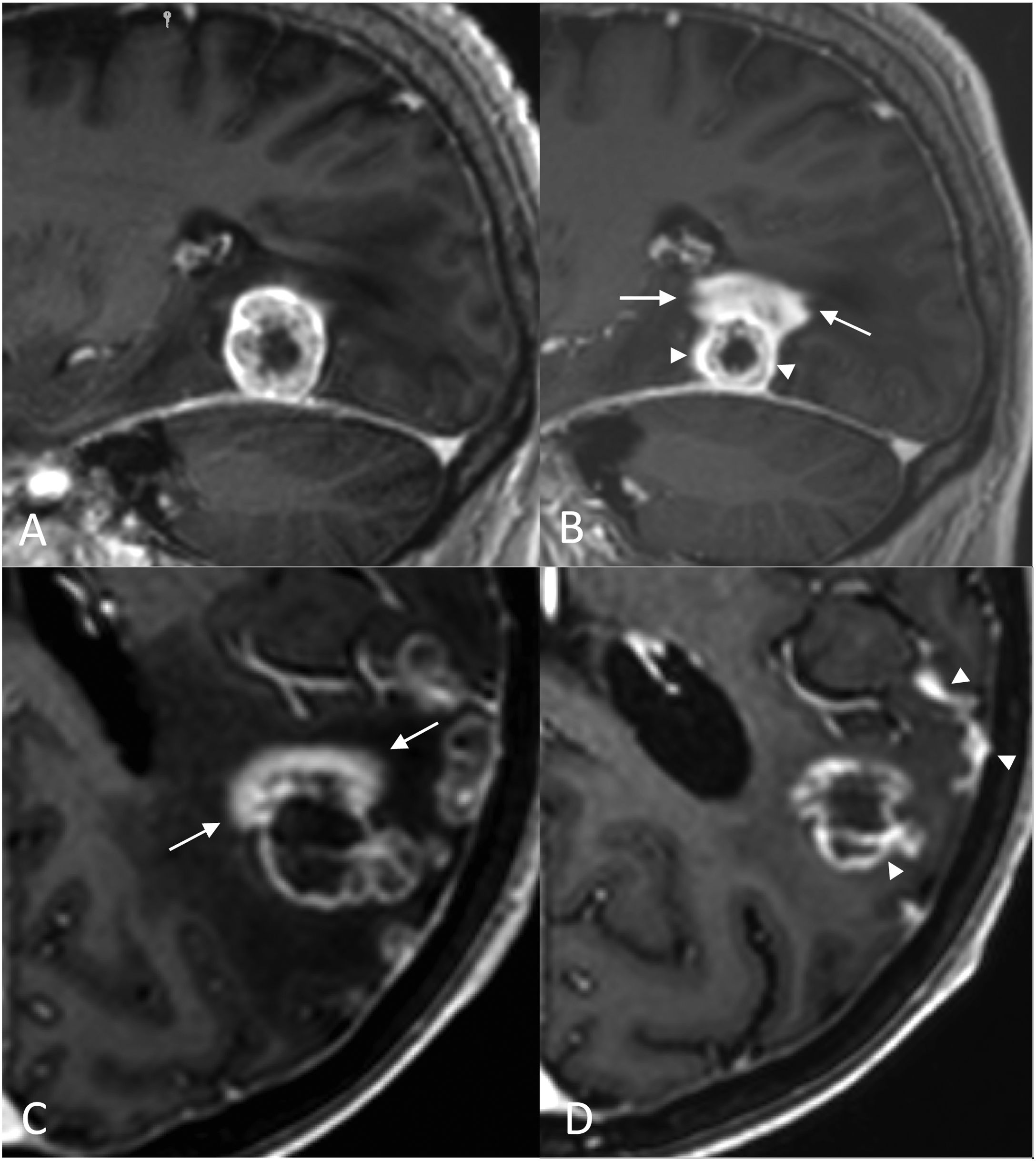

Radiologically, radiation necrosis is a highly patchy, irregular lesion with heterogeneous peripheral enhancement that resembles cut green pepper, Swiss cheese or soap bubbles.50 The tissue is disorganised and unstructured, with no delimitation of a mass when using basic sequences.49 Multiple punctate or linear areas are due to the presence of blood degradation products, calcifications and a liquefactive component (necrosis). If there is an ‘incomplete ring enhancement’ sign or a C shape (Fig. 7) with its opening towards the pial or ventricular surface, radiation necrosis is suspected.31 This could be attributed to the associated demyelination process.31

‘Incomplete ring enhancement’ sign open to the ependymal surface in two cases of radiation necrosis. Case 1: Breast cancer patient with brain metastasis (not shown) operated on and treated with RT. 3D T1-weighted cross-sectional images after fractionated RT treatment of the site, at six months (A) showing radiation necrosis with ‘C’ enhancement (arrow), open to the ependymal surface (*) of the right frontal horn, and at 13 months (B), showing regression of the lesion. Case 2: Patient with seminomatous type pineal germinoma treated with chemo- and radiotherapy (ventricular PTV): 32 Gy in 20 sessions of 1.6 Gy/session and PTV boost in the suprasellar region: 46 Gy in 20 sessions of 2.3 Gy/session. 3D T1-weighted cross-sectional images at two years (C) and at four years (D) after fractionated RT treatment. Areas of radiation necrosis (arrows) appear at 20 months (not shown) and maintain a progressive increase in size over five months until 24 months (C), after which they begin to decrease in size. Note the opening to the ependymal surface of the third ventricle (*) and the crossing of anatomical boundaries with non-communicating lesions in both thalami (another lesion was located in the corpus callosum, not shown).

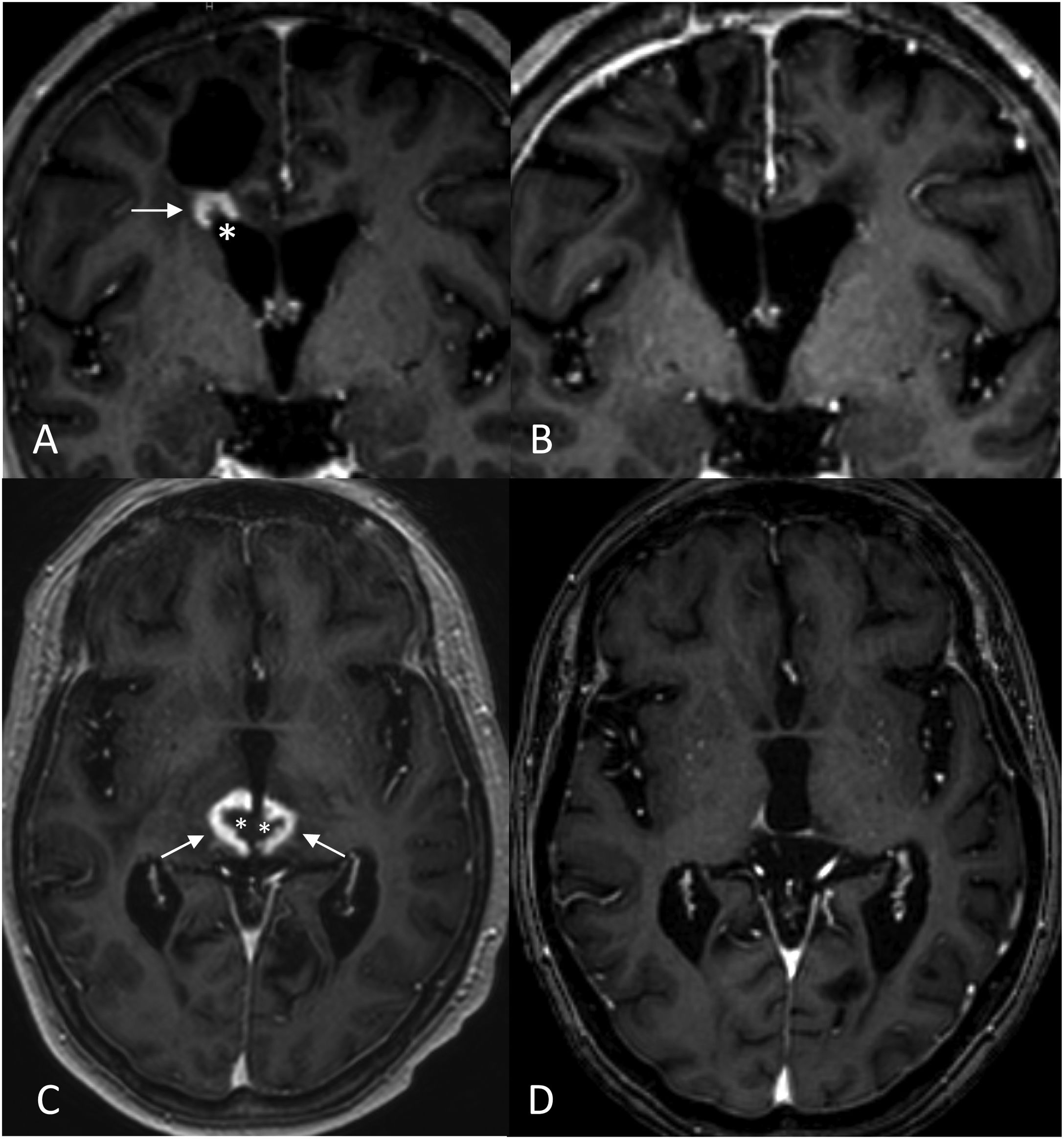

In addition, the area of aseptic coagulative necrosis can contain a viscous pus-like material with abundant polymorphonuclear leukocytes,52 which explains the restricted diffusion and the low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value identified in the centre of radiation necrosis mainly in the subacute phase (Fig. 8).31,40,53,54 Diffusibility increases over time, probably due to the degradation of blood products.

Diffusion in radiation necrosis. Breast cancer patient with an operated brain metastasis receiving radiotherapy on the surgical site (fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy with 40 Gy in 10 fractionations). At five months, whole brain RT was performed with a good response from multiple lesions. After 10 months, another lesion close to the site is treated with radiosurgery (20 Gy). At 18 months, the contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted cross-sectional image (A) shows a new lesion in the same irradiated area with peripheral patchy enhancement. In diffusion-weighted imaging (B) we identify central restriction (arrows), which suggests radiation necrosis. The follow-up at 27 months (C, D) confirms the suspicion, demonstrating a reduction of the lesion, oedema and restriction, having received no further treatment other than steroids. The central hypersignal at 27 months (C) corresponds to calcifications which are also seen on the non-contrast 3D T1-weighted sequence and on CT (not shown).

The RANO group recognises the need to use imaging techniques in addition to standard MRI in cases of suspected RT-related changes.21 Therefore, not all growth above 20% should be considered progression. Nor is waiting until the sixth month in patients treated with immunotherapy a guarantee that the finding signals tumour recurrence, given that radiation necrosis may progressively grow for more than a year before stabilising.31

MRI of brain metastasesThe basic MRI protocol typically includes T1-weighted, T2-weighted, T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR), diffusion-weighted and a 3D T1-weighted sequence both non-contrast and following the administration of a gadolinium-based contrast.55

Contrast-enhanced FLAIR is more sensitive than contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequences in the detection of LM disease.8

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) reconstructions are useful for detecting small metastases using a contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted sequence and reconstructions of four or five millimetres thickness.31

Immediate post-surgical MRI is necessary to estimate the tumour remnant. It should ideally be performed within the first 48 h, and no later than 72 h after surgery, to avoid ischaemic or inflammatory enhancements.56,57

When assessing response to treatment, tumour growth involves a complex differential diagnosis between tumour recurrence and treatment-related changes. This is where new MRI techniques play an important role.21 There is much ongoing research into diffusion and perfusion imaging, spectroscopy and PET, where several promising avenues of added value have already been identified.55

Diffusion-weighted imagingDiffusion refers to the random movement of water molecules. The ADC describes the rate of diffusional movement. The ‘b’ value represents the strength of the diffusion gradient, and is usually within the range of 900 to 1,000 s/mm2.38

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) can help us differentiate metastases from the annular enhancement of abscesses given that the latter have a viscous purulent content in the centre of the lesion that restricts diffusion.38

The role of DWI is indisputable in post-surgical studies as it reveals acute ischaemic infarction.58 In MRI follow-up scans, ischaemic enhancement could be misinterpreted as early recurrence if there is no knowledge of the pre-existing infarct in the area.38

The usefulness of DWI in response assessment is contingent on the presence of a tumour with a high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio, which most commonly translates to a lung, breast, colon or testicular tumour.59 In these cases, restriction of the enhancing component is expected. Conversely, tumour recurrence will not display restriction if the original metastasis did not. In general, treated lesions that are progressing well will decrease in size as the restriction subsides (Fig. 9). Conflicting results have been published on the relationship between the central diffusivity of the necrotic area and tumour progression,38,53 with most studies reporting increased central diffusion of the necrotic area in cases of tumour recurrence. Thus, the sign of central restriction in the necrotic area is suggestive of radiation necrosis.31,53,54

Patient with microcytic lung cancer treated with prophylactic whole brain radiotherapy; the patient progresses at six months (A and D). Treatment planning images for radiotherapy treatment with 35 Gy in 7 fractionations (A, D) at two months after radiotherapy treatment (B, E) and at four months (C, F). Contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted cross-sectional images (arrows) demonstrate a progressive reduction in the volume of the metastasis. The lesions in the diffusion-weighted images (*) exhibit a reduction in restriction in response to treatment.

The main techniques used to perform MR perfusion studies are dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC), dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) and Arterial Spin Labelling (ASL).60

DSC obtains information from the first passage of paramagnetic contrast through the cerebrovascular system. It estimates the relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV), which is a reflection of neoangiogenesis. This is a validated technique for the diagnosis and management of brain tumours.60

T1-weighted sequence DCE has some advantages over DSC in that it has a higher spatial resolution and is less susceptible to artefacts;60 however, acquisition times are longer. T1-weighted DCE enables the calculation of several parameters related to vascular permeability, such as Ktrans and plasma volume. Ktrans is a transfer constant that describes the diffusivity of gadolinium chelates through the capillary endothelium.60,61

ASL is a perfusion method that does not use contrast agents. It uses magnetised blood as an endogenous tracer. However, it is limited in comparisons to other methods by a low signal-to-noise ratio and a lower spatial resolution.60

DSC perfusion imaging is a valuable tool in the differential diagnosis of high-grade glioma from brain metastasis, due to the difference in peritumoural rCBV between the two types of tumours. This difference is explained by the absence of microscopic infiltration beyond the external enhancing margin of the metastasis. By contrast, the peritumoural region of gliomas harbours a combination of vasogenic oedema and infiltrative non-enhancing tumour tissue.62–65

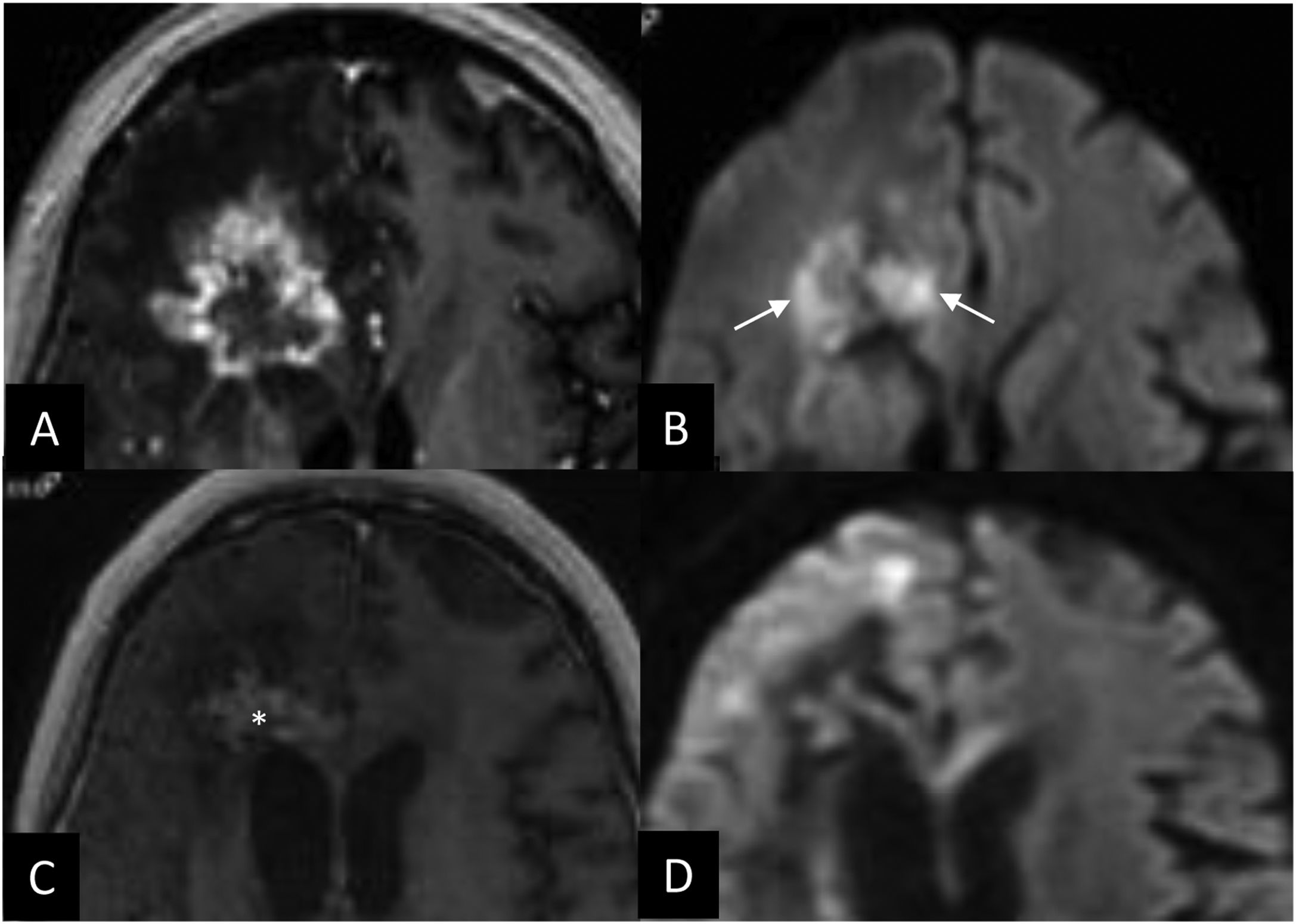

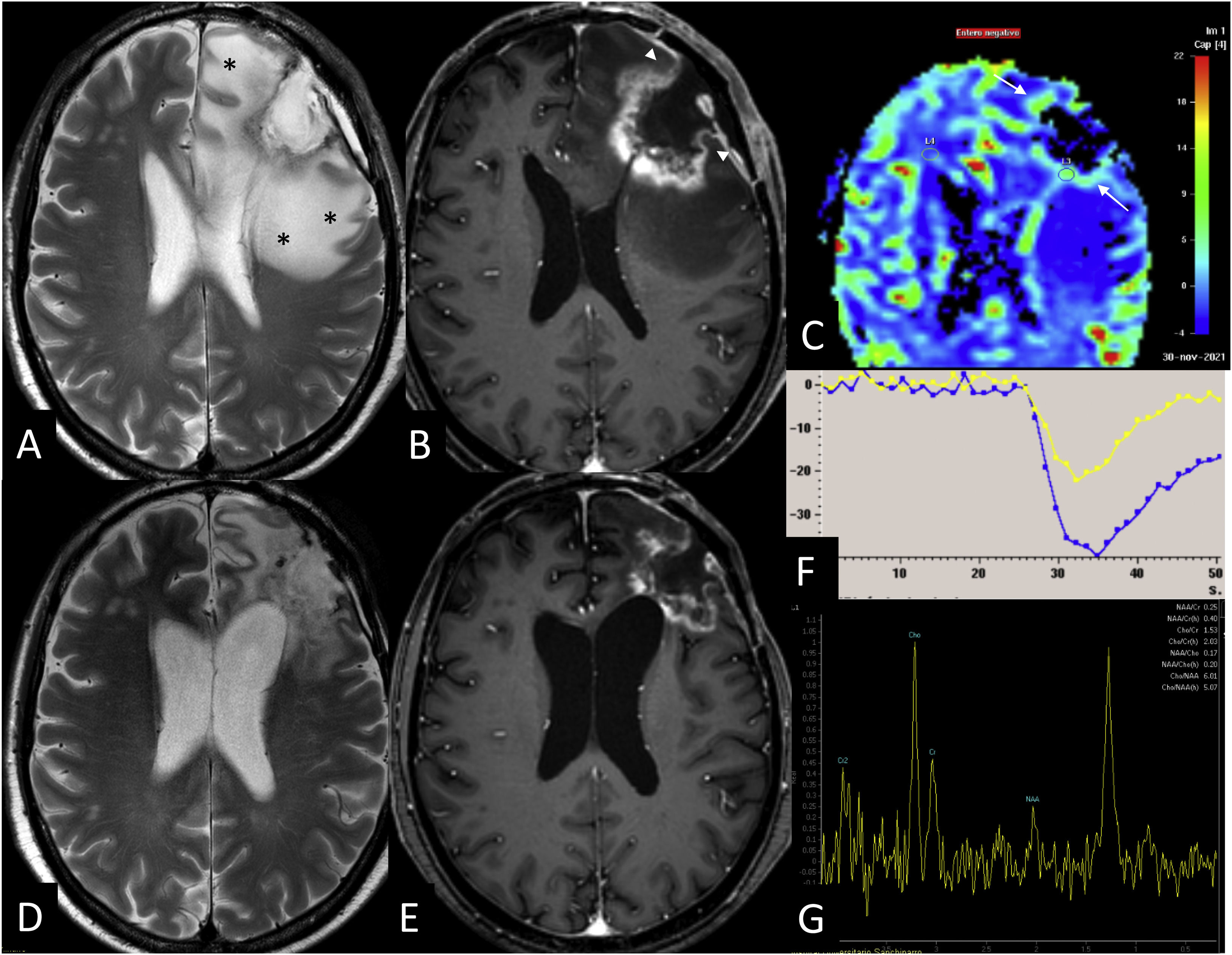

Perfusion imaging helps differentiate between tumour recurrence and radiation necrosis.61,66 Morabito et al.61 set an optimal cut-off point for rCBV at 1.23, with 88% sensitivity (sens.) and 75% specificity (spec.), while the cut-off point for the Ktrans constant was set at 28.76, with 89% sens. and 97% spec. Barajas et al.36 set a cut-off point for rCBV at 1.54 enabling the detection of recurrence with higher sens. and spec. values. In their series, all rCBV values are below 1.35 in radiation necrosis. Other authors suggest that an rCBV to grey matter that is greater than 1.85 excludes the possibility of radiation necrosis. However, the proximity of the metastases to the cerebral cortex and the size of the metastases limit the technique. Thus, the absence of an increase in rCBV does not rule out tumour progression, especially in cystic metastases, where the thin wall may result in an undetectable rCBV. These studies may include examples of radiation necrosis in chronic phases, and it is important to keep in mind that radiation necrosis typically exhibits an elevated rCBV in the acute phase (Fig. 10).31

Advanced MRI in radiation necrosis. Patient with adenocarcinoma of the colon with a left frontal brain metastasis treated with surgery and fractionated radiotherapy of the surgical site with 10 fractionations of 4 Gy. Six months after radiotherapy treatment (A, B, C, F, G) contrast-enhanced T2-weighted (A) and 3D T1-weighted (B) sequences demonstrate a lesion with peripheral enhancement and irregular margins. The T2* perfusion colour map (C) and time-signal intensity curve (F) reflect an increase in relative cerebral blood volume (arrows) of 2.9. The spectroscopy with TE of 144 ms (G) shows an increase in Cho/Cr and Cho/NAA ratios with a sharp lipid peak. However, the type of enhancement and the extensive oedema (*), as well as the thinning of the enhancement towards the pial surface (arrowhead), should raise suspicion of radiation necrosis. Subsequent follow-up MRI (D,E) demonstrates a reduction in size confirming the suspicion of radiation necrosis.

DCE and ASL also play a role in the differential diagnosis between high-grade gliomas and metastasis.62

Magnetic resonance spectroscopyMagnetic resonance spectroscopy evaluates the chemical content of a volume of tissue and generates a frequency spectrum expressed in parts per million (ppm). Multiple metabolites have proven useful in clinical practice.60 N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) is a marker of neuronal viability and resonates at 2 ppm chemical shift. Choline (Cho) is a marker of cell membrane turnover and resonates at 3.2 ppm chemical shift. Lactate is a marker of metabolism and resonates at 1.3 ppm chemical shift. Myo-inositol is a marker of gliosis and resonates at 3.5 ppm chemical shift. Creatine (peak at 3 ppm chemical shift) is assumed to be stable and is used as an internal standard.60,67

Elevated Cho/NAA levels in tumours are associated with higher cell density, proliferation rate and cell death rate. Elevated levels of Cho, lactate and lipids are seen in metastases.67 NAA is absent in metastases due to the lack of neurons. Spectroscopy enables peritumoural infiltration analysis which can be used to differentiate metastasis from a primary tumour. Glioblastomas tend to exhibit elevated choline/creatine ratios and lymphomas have higher Co/Cr and lipid-lactate/Cr ratios than metastases.60,65,68,69

In response assessment, MR spectroscopy alone provides a moderate diagnostic performance due to the fact that treatment-related changes, including radiation necrosis, reveal elevated Cho/Cr and Cho/NAA ratios (Fig. 10), attributable to a higher cell membrane turnover.70

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)PET uses a variety of radiotracers which identify different metabolic pathways. It is a complementary test used in the differential diagnosis of tumour recurrence from treatment-induced changes. 18F-fluorodeoxy-glucose (18F-FDG) is not the ideal radiotracer for brain tumour assessment due to the high physiological uptake in the brain, although, thanks to dual-time-point imaging, late acquisition improves diagnostic sensitivity.71 Radiolabelled amino acid-based tracers have proved to be a useful tool in metastasis response assessment, specifically 11C-methyl-methionine (11C-MET).72 Others have also attracted considerable interest, such as 18F-fluorophenylalanine (18F-DOPA) and 18F-fluoroethyl-L-tyrosine (18F-FET), as the 18F-fluorine content improves their availability.73 These techniques provide good diagnostic accuracy, although they can give rise to false positives in situations that alter the blood-brain barrier (ischaemia, haemorrhage, infection or demyelination). Acute-phase radiation necrosis exhibits intense uptake of FDG and other radiotracers.74,75

ConclusionBrain metastasis response assessment after RT treatment remains a challenge both clinically and radiologically. The multiparametric approach is most useful when growth is detected after treatment. However, the presence of abrupt and exponential growth after RT, even when advanced techniques suggest tumour recurrence, should be analysed with caution as it is likely to correspond to inflammatory changes. In these cases, close and regular follow-up often confirms the suspicion as the lesion regresses. For this reason, it is important that the type of treatment received is made known and a multidisciplinary approach is applied in the assessment in order to avoid unnecessary aggressive management or withdrawal from a clinical trial.

FundingThis research has not received funding support from public sector agencies, the business sector or any non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Our sincere thanks to Julián Pérez-Beteta PhD (Mathematical Oncology Laboratory) and Pablo Cardinal MD, PhD, for their help in the statistical analysis of the doctoral thesis that sparked our interest in the radiological assessment of brain metastases.