To compare the myocardial perfusion reserve index (MPRI) measured during stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with regadenoson in patients with heart transplants versus in patients without heart transplants.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively compared 20 consecutive asymptomatic heart transplant patients without suspicion of microvascular disease who underwent stress cardiac MRI with regadenoson and coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) to rule out cardiac allograft vasculopathy versus 16 patients without transplants who underwent clinically indicated stress cardiac MRI who were negative for ischemia and had no signs of structural heart disease. We estimated MPRI semiquantitatively after calculating the up-slope of the first-pass enhancement curve and dividing the value obtained during stress by the value obtained at rest. We compared MPRI in the two groups. Patients with positive findings for ischemia on stress cardiac MRI or significant coronary stenosis on coronary CTA were referred for conventional coronary angiography.

ResultsMore than half the patients remained asymptomatic during the stress test. Stress cardiac MRI was positive for ischemia in two heart transplant patients; these findings were confirmed at coronary CTA and at conventional coronary angiography. Patients with transplants had lower end-diastolic volume index (59.3 ± 15.2 ml/m2 vs. 71.4 ± 15.9 ml/m2 in those without transplants, p = 0.03), lower MPRI (1.35 ± 0.19 vs. 1.6 ± 0.28 in those without transplants, p = 0.003), and a less pronounced hemodynamic response to regadenoson (mean increase in heart rate 13.1 ± 5.4 bpm vs. 28.5 ± 8.9 bpm in those without transplants, p < 0.001).

ConclusionStress cardiac MRI with regadenoson is safe. In the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease, patients with heart transplants have lower MPRI than patients without transplants, suggesting microvascular disease. The hemodynamic response to regadenoson is less pronounced in patients with heart transplants than in patients without heart transplants.

Comparar el índice de reserva de perfusión miocárdica (IRPM) medido por resonancia magnética cardíaca de estrés (RMC-estrés) con regadenosón en sujetos trasplantados frente a no trasplantados.

Material y métodosSe compararon, de forma retrospectiva, 20 trasplantados cardíacos consecutivos, asintomáticos y sin sospecha clínica de enfermedad microvascular, a quienes se realizó RMC-estrés con regadenosón y coronariografía por TC (CTC) para descartar enfermedad vascular del injerto (EVI) respecto a 16 sujetos no trasplantados, con RMC-estrés realizada por indicación clínica, negativa para isquemia y sin signos de cardiopatía estructural. El IRPM se estimó de forma semicuantitativa tras calcular el valor de la pendiente durante la perfusión de primer paso y dividir el valor obtenido en estrés respecto al reposo. Se comparó IRPM en ambos grupos. Los pacientes con RMC-estrés positiva para isquemia o CTC con estenosis coronaria significativa fueron derivados a coronariografía convencional.

ResultadosMás de la mitad de los sujetos permanecieron asintomáticos durante la prueba de estrés. La RMC-estrés resultó positiva para isquemia en dos trasplantados, que se confirmó mediante CTC y coronariografía convencional. Los pacientes trasplantados presentaron menor volumen telediastólico indexado (59,3 ± 15,2 ml/m2 frente a 71,4 ± 15,9 ml/m2, p = 0,03), menor IRPM (1,35 ± 0,19 vs. 1,6 ± 0,28, p = 0,003 y menor respuesta hemodinámica al regadenosón que los no trasplantados (incremento medio de la frecuencia cardíaca de 13,1 ± 5,4 lpm frente a 28,5 ± 8,9 lpm, p < 0,001).

ConclusiónLa RMC-estrés con regadenosón es una técnica segura. En ausencia de enfermedad coronaria epicárdica significativa, los trasplantados presentan menor IRPM que los no trasplantados, lo que sugiere enfermedad microvascular. En pacientes trasplantados, la respuesta hemodinámica esperable al regadenosón es menor que en no trasplantados.

Heart transplant is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage heart failure.1 In this population, graft vascular disease (GVD) continues to be the main cause of graft failure and death after the first year post-transplant. GVD is a form of accelerated atherosclerosis involving vascular infiltration by lipid-laden macrophages and is a consequence of chronic rejection. Although the pathogenesis is not fully understood, one theory is that GVD may develop as a result of a chronic immune response caused by both immunological and non-immunological factors.2 It manifests as a diffuse and concentric thickening of the intimal layer of the graft's epicardial and intramural arteries.2 In surveillance studies, it is estimated that after the first year post-transplant, around 58% of patients have significant intimal thickening measured by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), and that at five years, 42% of patients have some angiographic sign of GVD.2

Because of the clinical significance of GVD, transplant patients undergo strict monitoring and annual check-ups. Imaging tests play a key role in the follow-up process. The reference standard for diagnosing GVD is conventional coronary angiography with IVUS. However, in the context of heart transplants, with the risk of distal microvascularisation and, particularly to detect subclinical GVD, functional imaging techniques may be more helpful than anatomical tests. It was recently found in studies with positron emission tomography (PET) that transplant recipients have decreased myocardial flow values compared to non-transplanted subjects.3 Other studies have also shown that cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) can be used for early detection of graft microvascular disease in this population, both with conventional studies4 and with stress protocols, which also allow us to analyse myocardial perfusion5. Most of these studies on perfusion were carried out using traditional vasodilator drugs (adenosine and dipyridamole).6 However, adenosine may be somewhat contraindicated in heart transplant patients, as the sinus node of the denervated heart is more sensitive to exogenous adenosine than the innervated node. This group of patients is therefore potentially at increased risk of prolonged atrioventricular block.7,8 Very little is known about the utility of regadenoson in this clinical context.9

We conducted this study to establish the diagnostic utility of stress CMR with regadenoson for detecting microvascular dysfunction in heart transplant patients. We suggest that stress CMR could detect GVD in early stages and be useful in the clinical management of these patients.

Material and methodsSubjectsTwenty consecutive patients with orthotopic heart transplant who underwent stress CMR and computed tomography coronary angiogram (CTCA) were retrospectively studied to rule out GVD within a time interval of less than one week. The patients were asymptomatic at the time of the study and there was no clinical reason to suspect microvascular disease. These patients were compared with 16 control subjects matched for age and gender who had not been transplanted, but who underwent stress CMR for clinical indication and whose result was negative, with no late gadolinium enhancement or other signs of structural heart disease. We excluded transplant recipients with symptoms suggestive of ischaemia, clinically suspected microvascular disease or unstable haemodynamic status. Patients were asked not to drink coffee or other drinks or foods containing stimulants for 24 h before the examination. The study protocol was approved by our centre's ethics committee (project 149/2015) and all patients signed the informed consent form to participate in the study.

Stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging protocolThe CMR studies were performed with a 1.5 T kit (Magnetom Aera, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany), with a six-channel surface coil. A conventional rest/stress CMR protocol was used which included specific sequences to assess the anatomy and function of the heart and myocardial perfusion and tissue characterisation sequences.10 Regadenoson (Rapiscan, GE Healthcare) administered as a single intravenous dose of 0.4 mg (5 ml) was used as vasodilator agent to induce the stress. The drug was administered by manual infusion over about 10 s. The stress perfusion study was carried out approximately 70 s after the administration of the vasodilator in three representative slices of the left ventricle (base, mid-ventricular and apical), with a TurboFLASH sequence (TR: 2.96 ms; TE: 1.1 ms; matrix: 160 × 82; field of vision: 380 × 285 mm; voxel size: 2.4 × 2.4 × 10 mm; 10 mm slice thickness, 59 segments, 50 acquisitions), during the administration of 0.075 mmol/kg body weight of gadobutrol (Gadovist, Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany) at a flow rate of 4 ml/s, with a double-head injector (Medrad Inc., Warrendale, Pennsylvania, United States). The perfusion at rest was carried out 10 min after the vasodilator agent infusion, using the same sequence and the same contrast injection protocol. Intravenous euphyllin (200 mg) was used immediately after the stress infusion to reverse the effect of the regadenoson.10

Patients were monitored throughout the procedure by measuring blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) and any adverse effects that might have been related to the administered drug were recorded, such as bronchospasm, atrioventricular block, arrhythmias, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, need for hospital admission, myocardial infarction or death.

To determine the haemodynamic effect of regadenoson, BP and HR were taken at rest and under pharmacological stress and the difference was calculated (peak HR – baseline HR and peak BP – baseline BP).

Computed tomography-coronary angiogram protocolThe CTCA were performed with a dual-source CT scanner (SOMATOM Definition, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany), with the patient supine, during inspiration, craniocaudal view and retrospective ECG synchronisation; 120 kVp, 350 mA were used for each tube, with a slice thickness 64 × 0.6 mm; collimation 64 × 0.6 mm; gantry rotation time 330 ms; and temporal resolution 83 ms. A variable pitch (0.2−0.45) adapted to the HR was used. The tube current was modulated automatically (ECG pulsing), with the maximum radiation dose being administered from 35% to 70% of the cardiac cycle and the nominal tube current reduced to 5% in the rest of the phases. The studies were acquired after injecting 70 ml of iodinated contrast (Iohexol, Omnipaque™ 300 mg/ml, General Electric, Madrid) followed by a bolus of 50 ml of normal saline through an antecubital vein at a constant flow rate of 5 ml/s with a dual syringe injector (Stellant CT, Medrad Inc. Indianola, USA). The delay time was calculated using the bolus tracking technique with the region of interest put in the ascending aorta and a trigger threshold of 100 Hounsfield units (HU). The images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 0.75 mm, reconstruction increment of 0.4 mm and soft particle filter (B26f). Images were filed in the hospital's digital archive system (Picture Archiving and Communication System, PACS).

Analysis of the studiesThe studies were assessed separately by two independent radiologists. One radiologist with 16 years of experience in cardiac radiology analysed the CTCA studies without knowing the results of the CMR and another with three years of experience analysed the CMR studies without knowing the CTCA results. The CMR studies were analysed on a workstation equipped with a specific program (cmr 42, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., Calgary, Canada). For the assessment of ventricular function, the endocardial and epicardial contours of the left ventricle were manually traced on the end-diastolic and end-systolic images obtained on the short axis.11 LThe papillary muscles were excluded from the volumetric calculation and included as myocardial mass. Ejection fraction (EF), end-diastolic volume (EDV), end-systolic volume (ESV) and myocardial mass were obtained. The parameters were indexed by body surface area.

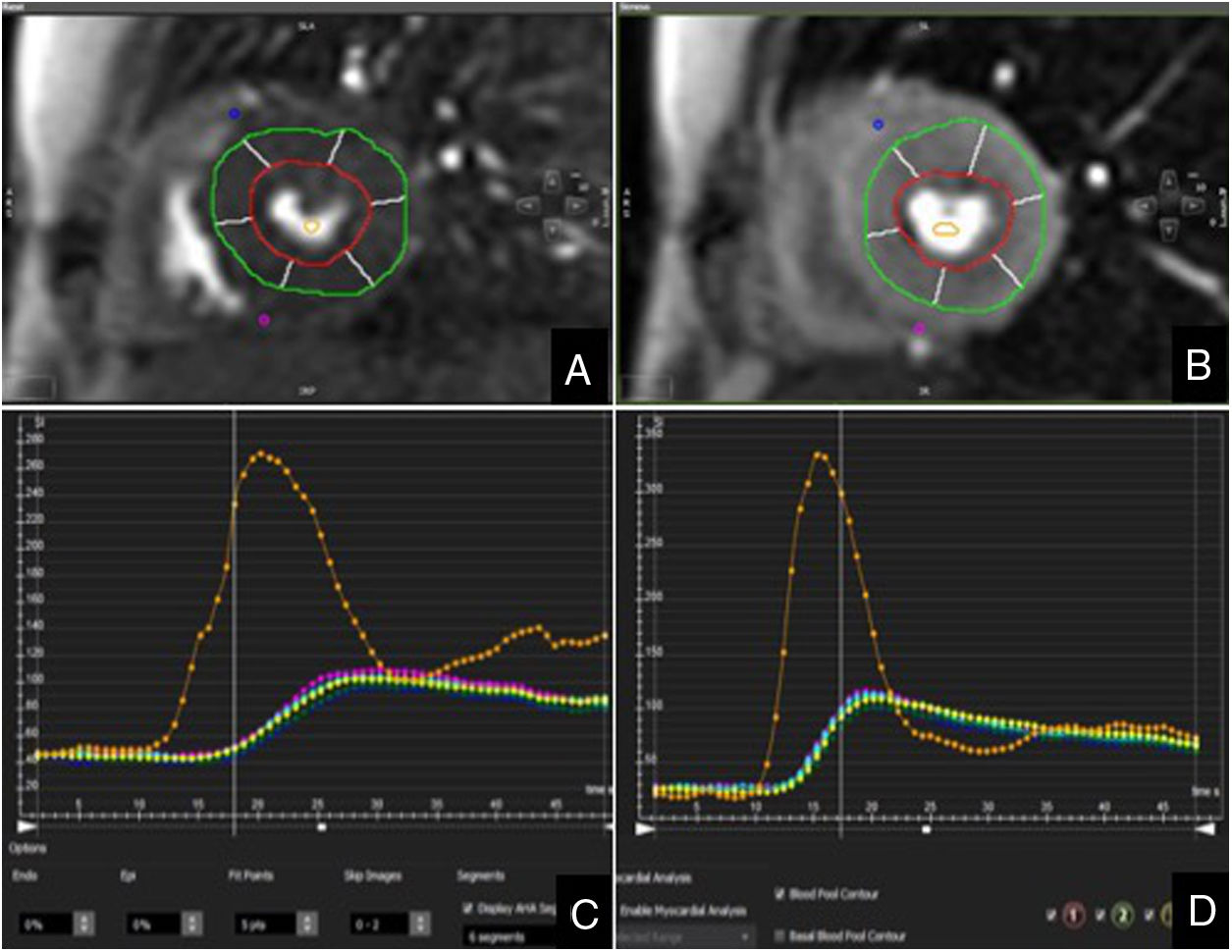

Analysis of myocardial perfusion was performed qualitatively and semi-quantitatively. For qualitative or visual analysis, the left ventricle was divided into six equiangular segments in the base and mid-ventricular slices and four segments in the apical slice, as per American Heart Association recommendations.12 The images acquired under stress and at rest were evaluated simultaneously in the same viewer and in cinema mode. Ischaemia was diagnosed on detection in a myocardial segment of lack of enhancement in the stress perfusion sequence, normal enhancement in the resting perfusion sequence and no hypersignal in the late enhancement sequence. The semi-quantitative analysis was carried out in the mid-ventricular segments. Endocardial and epicardial contours were first manually traced, excluding the innermost (10%) and outermost (30%) myocardium to avoid partial volume artefact. Subsequently, the ventricular junction points were defined to divide the myocardium into six equiangular segments and a region of interest was drawn in the ventricular cavity as a sample of the blood content. Last of all, the contours were propagated to all the images. The myocardial signal intensity was then determined at all time points to calculate the time to peak, the perfusion index and the slope for each myocardial segment, both under stress and at rest (Fig. 1). The slope values were corrected by the signal intensity of the ventricular cavity to compensate for any changes in the compaction and speed of the contrast bolus.13,14 The myocardial perfusion reserve index (MPRI) was calculated after dividing the slope into maximum vasodilation (stress) with respect to rest.15 An MPRI < 1.2 was considered abnormal.16 Incomplete or poor quality studies were excluded from the analysis. We also excluded myocardial segments which showed late gadolinium enhancement secondary to infarction.

The CTCA were analysed with commercial software equipped with advanced cardiac post-processing tools (syngo.via, Siemens Healthineers), using the CAD-RADS (Coronary Artery Disease Reporting and Data System) terminology17, such that significant coronary stenosis was considered as that with a 50% or greater reduction in the diameter of the vessel lumen (CAD-RADS ≥3).

Patients with stress CMR positive for ischaemia or CTCA with significant coronary stenosis were referred for conventional coronary angiography, with a 50% or greater reduction in the diameter of the vessel lumen being considered as a positive result. The analysis of the CMR studies was carried out by myocardial segments and the correlation between CTCA and conventional coronary angiography, by vessel.

Statistical analysisThe data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for the quantitative variables and as frequencies and percentages for the qualitative variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the distribution of the data. We used Student's t test for independent samples, in order to compare subject characteristics, ventricular parameters, changes in HR and BP and the differences in the MPRI. For the statistical analysis we used the SPSS program for Mac (version 20.0/SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

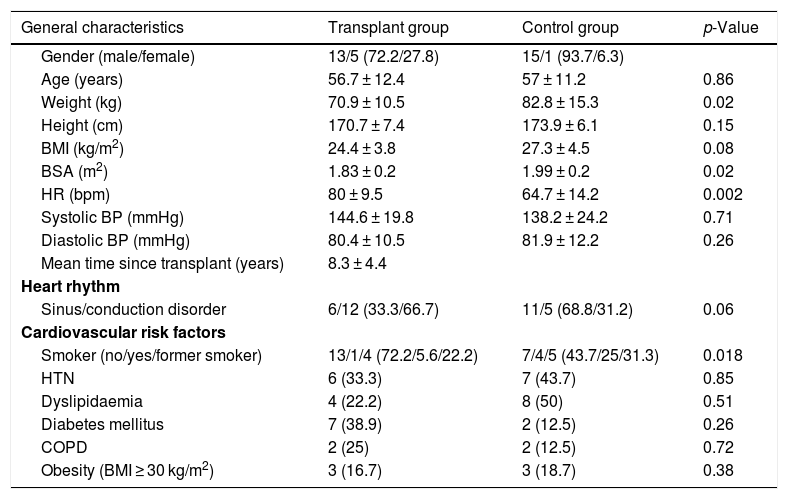

ResultsStudy populationOf the 20 patients initially transplanted, two were excluded due to technical problems during the acquisition of the MRI study. Of the 18 patients analysed, 13 were male and five female, with a mean age of 56.7 ± 12.4 years. The mean time from transplant to the CMR study was 8.3 ± 4.4 years. Of the 16 control patients, 15 were male and one female, with a mean age of 57 ± 11.2 years. The transplant recipients had a higher baseline HR than those in the control group. However, the controls weighed more and had a larger body surface area than the transplant recipients (p = 0.02 and p = 0.02, respectively). Table 1 shows the general demographic characteristics, heart rate at the time of the study and the cardiovascular risk factors for both groups.

Clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study.

| General characteristics | Transplant group | Control group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 13/5 (72.2/27.8) | 15/1 (93.7/6.3) | |

| Age (years) | 56.7 ± 12.4 | 57 ± 11.2 | 0.86 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.9 ± 10.5 | 82.8 ± 15.3 | 0.02 |

| Height (cm) | 170.7 ± 7.4 | 173.9 ± 6.1 | 0.15 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.4 ± 3.8 | 27.3 ± 4.5 | 0.08 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.83 ± 0.2 | 1.99 ± 0.2 | 0.02 |

| HR (bpm) | 80 ± 9.5 | 64.7 ± 14.2 | 0.002 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 144.6 ± 19.8 | 138.2 ± 24.2 | 0.71 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80.4 ± 10.5 | 81.9 ± 12.2 | 0.26 |

| Mean time since transplant (years) | 8.3 ± 4.4 | ||

| Heart rhythm | |||

| Sinus/conduction disorder | 6/12 (33.3/66.7) | 11/5 (68.8/31.2) | 0.06 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Smoker (no/yes/former smoker) | 13/1/4 (72.2/5.6/22.2) | 7/4/5 (43.7/25/31.3) | 0.018 |

| HTN | 6 (33.3) | 7 (43.7) | 0.85 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 4 (22.2) | 8 (50) | 0.51 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (38.9) | 2 (12.5) | 0.26 |

| COPD | 2 (25) | 2 (12.5) | 0.72 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 3 (16.7) | 3 (18.7) | 0.38 |

BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HTN: hypertension. Percentages are given in brackets.

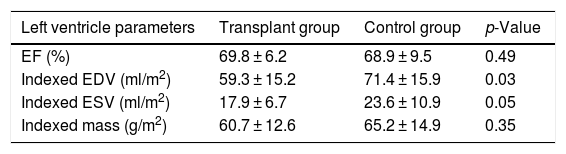

The results of the stress CMR study are summarised in Table 2. Compared to the control group, the transplant patients had a lower indexed EDV (59.3 ± 15.2 ml/m2 vs. 71.4 ± 15.9 ml/m2, p = 0.03). Concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle was identified in 38.9% of the transplant patients, concentric remodelling in 27.8% and normal morphology in 33.3%. In the control group, most patients (75%) had normal left ventricular morphology, 12.4% had concentric remodelling, 6.3% concentric hypertrophy and 6.3% eccentric hypertrophy.

Comparison of left ventricular volumes and ejection fraction in transplant patients and the control group.

| Left ventricle parameters | Transplant group | Control group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EF (%) | 69.8 ± 6.2 | 68.9 ± 9.5 | 0.49 |

| Indexed EDV (ml/m2) | 59.3 ± 15.2 | 71.4 ± 15.9 | 0.03 |

| Indexed ESV (ml/m2) | 17.9 ± 6.7 | 23.6 ± 10.9 | 0.05 |

| Indexed mass (g/m2) | 60.7 ± 12.6 | 65.2 ± 14.9 | 0.35 |

EDV: end-diastolic volume; EF: ejection fraction; ESV: end-systolic volume.

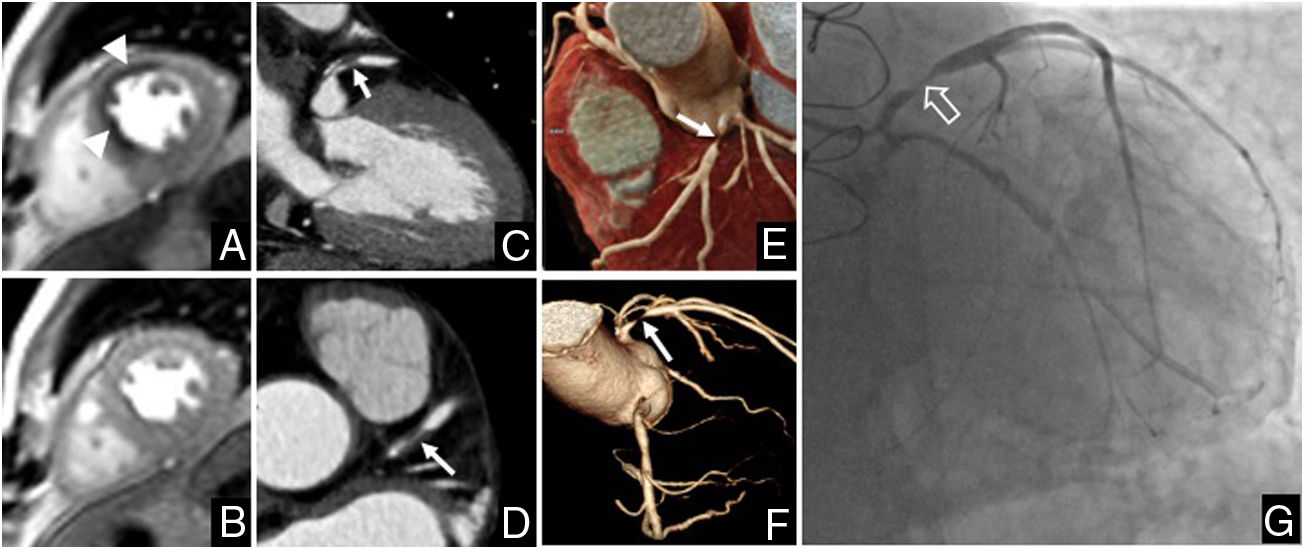

In the qualitative analysis, the stress test was positive in two transplant patients (11.1%). Ischaemia was identified in the anterior and anteroseptal segments in one patient and in the anterior and anterolateral segments in another patient. In CTCA, stenosis of 70%–99% was observed in the proximal segment of the anterior descending coronary artery in one patient and of 70%–99% in the intermediate branch in another patient, both of which were confirmed by conventional coronary angiography (Fig. 2). All the transplant recipients with negative stress CMR had CAD-RADS <3 in CTCA.

Study in a 65-year-old male patient given a heart transplant 15 years earlier due to coronary heart disease-related heart failure. A) Stress CMR perfusion. B) Resting CMR perfusion. The study showed myocardial ischaemia in the anterior and mid anteroseptal segments (arrowheads). C to F) Computed tomography coronary angiogram (CTCA). C and D) Multiplanar reconstruction. E) Cinematic rendering. F) Volume rendering of the coronary tree. On CTCA, stenosis of 70%–99% was observed in the proximal segment of the anterior descending coronary artery (arrows), which was confirmed by catheterisation (empty arrow in G).

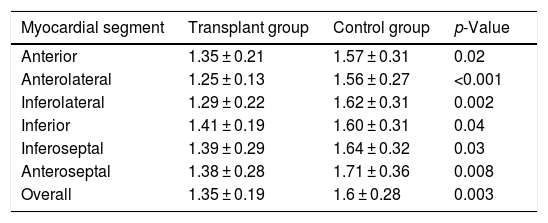

The semi-quantitative analysis confirmed an MPRI < 1.2 in the ischaemic segments. An MPRI of 1.1 was observed in one patient in the anterior and anteroseptal segments. In another patient, the MPRI was 1 in the anterior segment and 1.1 in the anterolateral segment. The transplant recipients with negative stress CMR had a lower MPRI than the subjects in the control group, both analysing overall (1.35 ± 0.19 vs. 1.6 ± 0.28, p = 0.003) and by myocardial segments (Table 3).

Comparison by myocardial segments (midventricular section) of myocardial perfusion reserve indices between transplant recipients with negative stress CMR and the control group.

| Myocardial segment | Transplant group | Control group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | 1.35 ± 0.21 | 1.57 ± 0.31 | 0.02 |

| Anterolateral | 1.25 ± 0.13 | 1.56 ± 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Inferolateral | 1.29 ± 0.22 | 1.62 ± 0.31 | 0.002 |

| Inferior | 1.41 ± 0.19 | 1.60 ± 0.31 | 0.04 |

| Inferoseptal | 1.39 ± 0.29 | 1.64 ± 0.32 | 0.03 |

| Anteroseptal | 1.38 ± 0.28 | 1.71 ± 0.36 | 0.008 |

| Overall | 1.35 ± 0.19 | 1.6 ± 0.28 | 0.003 |

Most of the transplant recipients had a non-ischaemic late gadolinium enhancement pattern (72.2%). No enhancement suggestive of infarction was found. None of the patients in the control group had late gadolinium enhancement.

Clinical symptoms, safety and haemodynamic response of regadenosonMore than half of the transplant recipients remained asymptomatic during the administration of regadenoson (55.6%). The most common clinical symptoms were central chest tightness (16.7%) and reddening of the face (16.7%). One patient reported dyspnoea and another, palpitations. A similar pattern was found in the control group, with ten (62.5%) patients remaining asymptomatic, three (18.7%) reporting dyspnoea, two (12.5%) central chest tightness and one (6.3%) reddening of the face. There were no complications requiring medical attention. None of the patients required hospital admission.

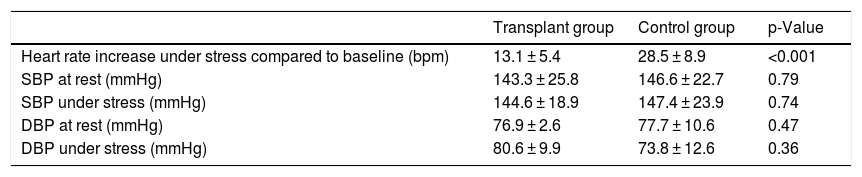

As an effect of the regadenoson-induced vasodilation, we found an increase in HR of 13.1 ± 5.4 bpm in the transplant recipients and 28.5 ± 8.9 bpm in the control group patients (p < 0.001). The mean figures for systolic and diastolic BP under stress and at rest were similar in the two groups (Table 4).

Comparison of haemodynamic response parameters (heart rate and blood pressure) induced by regadenoson between transplant recipients and the control group.

| Transplant group | Control group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate increase under stress compared to baseline (bpm) | 13.1 ± 5.4 | 28.5 ± 8.9 | <0.001 |

| SBP at rest (mmHg) | 143.3 ± 25.8 | 146.6 ± 22.7 | 0.79 |

| SBP under stress (mmHg) | 144.6 ± 18.9 | 147.4 ± 23.9 | 0.74 |

| DBP at rest (mmHg) | 76.9 ± 2.6 | 77.7 ± 10.6 | 0.47 |

| DBP under stress (mmHg) | 80.6 ± 9.9 | 73.8 ± 12.6 | 0.36 |

bpm: beats per minute; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; mmHg: millimetres of mercury; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

This study underlines the utility of stress CMR for an overall assessment of the transplanted heart. In addition to quantifying ventricular parameters and characterising myocardial tissue, the perfusion study enabled myocardial ischaemia to be detected in this group of patients, and identified a reduction in MPRI, a finding suggestive of microvascular dysfunction.

CMR is currently recommended as an alternative to echocardiography in heart transplant patients with a poor acoustic window, in order to establish the volumes and function of the heart chambers, exclude acute rejection and/or monitor GVD.18 CMR provides an exact measurement of the volumes and ejection fraction of both ventricles. Furthermore, using the late gadolinium enhancement sequences or newer techniques such as the T1 and T2 parametric maps, CMR enables changes in the myocardial structure to be quantified, and detection of tissue alterations, such as oedema and fibrosis, secondary to acute rejection or GVD.4,19–21 In the specific case of stress CMR, a reduction in myocardial blood flow has been shown in patients with GVD compared to the normal population which allows the severity of the vascular disease to be stratified.5,22 Our study produced similar results. We found that the transplant recipients with negative stress CMR had lower MPRI than the control group patients (1.35 ± 0.19 compared to 1.6 ± 0.28, p = 0.003), a finding also similar to that in PET studies, in which the transplanted patients had lower myocardial perfusion values compared to the control group in the absence of qualitative perfusion defects.3 A lower myocardial perfusion index suggests the existence of microvascular dysfunction secondary to GVD, a phenomenon in which the epicardial coronary arteries do not show significant lesions, but there is involvement of the distal microvascularisation. In fact, it has been suggested that the resting endocardial/epicardial perfusion ratio may be sufficient to diagnose GVD after excluding hypertrophy and prior rejection.5 The process of hypertrophy and ventricular remodelling that occurs in transplant patients implies an imbalance between the supply and demand of oxygen by the myocardium, such that the myocardial perfusion reserve is reduced. Our transplant population had a significantly lower indexed EDV than the patients in the control group, with altered ventricular morphology associated with the above remodelling process found in two thirds of the subjects. Another consequence of the involvement of the microvasculature is that micro-infarcts can occur, which could explain the late gadolinium enhancement foci. In our group, we observed gadolinium deposition in 72.2% of the transplant recipients.

One distinctive aspect of our study is that regadenoson was used as vasodilator agent. Stress CMR studies have traditionally been performed with adenosine or dipyridamole, although debate surrounds their safety, as adenosine can cause prolonged atrioventricular block in transplant recipients due to the increased sensitivity of the denervated heart to exogenous adenosine.7,8 To our knowledge, this is the second study to assess the efficacy and safety of regadenoson in CMR studies on heart transplant patients.9 In our cohort, we found that the majority of patients (55.6% of transplant recipients and 62.5% of non-recipients) remained asymptomatic during administration and that no adverse effects occurred, underlining the safety of the drug. Adverse reactions are not uncommon when using other vasodilators. For example, in the Adenoscan study, in which adenosine was used, side effects were detected in most patients (81.1%).23 Similarly, in studies carried out with dipyridamole, Rahnosky et al. found two cases of death from myocardial infarction, six cases of myocardial infarction and six cases of acute bronchospasm in a cohort of 3911 patients.24 The lower incidence of adverse effects associated with regadenoson could be explained by its mechanism of action, which is selective for the adenosine A2a receptor. This would avoid the action on the A1, A2b and A3 receptors responsible for the bronchospasm and high-grade atrioventricular block which can occur when using the other vasodilators.

One interesting observation of our study was that, as a haemodynamic response induced by regadenoson, there was less increase in HR in transplant recipients than in the control group (13.1 ± 5.4 bpm compared to 28.5 ± 8.9 bpm, p < 0.001). This may be due to the autonomic dysfunction that characterises the transplanted heart. Being denervated, the graft works independently, without responding physiologically to endogenous or exogenous stimuli that regulate its function, and does not therefore respond to the tachycardia stimulus in the same way as a physiologically normal heart.

This study has its limitations. We included only a small number of patients. However, our findings are in line with those published by other groups. Perfusion defects attributable to epicardial artery disease were observed in two patients in our study. One multicentre study reported that coronary heart disease was found in 42% of transplant recipients five years after transplantation; mild in 27%, moderate in 8% and severe in 7%.25 The post-transplant period in which the CMR study was performed was variable and there was no assessment of the association between the time since transplant and the CMR findings. The existence of microvascular disease was not subsequently verified to confirm the CMR findings. Moreover, conventional coronary angiography was not available for all patients. Nevertheless, all transplant recipients had a CTCA, a technique with a high negative predictive value for ruling out significant coronary disease in this group of subjects.26 Lastly, the MPRI was measured semi-quantitatively. These findings need to be corroborated with new CMR perfusion techniques, which enable a quantitative assessment of myocardial blood flow.27,28

In conclusion, CMR, and stress CMR in particular, is a technique that enables overall assessment of the heart graft in the transplant recipient. Even with negative stress CMR, transplant recipients have lower MPRI than non-transplant subjects, possibly reflecting dysfunction at the microvascular level. Regadenoson is a safe vasodilator drug and well tolerated by transplant recipients, although the expected haemodynamic response is less than in normal subjects, probably due to the autonomic dysfunction characteristic in these patients. Further studies are required to confirm our results and establish the clinical utility of CMR, in order to stratify the risk and determine its prognostic value in the surveillance of this group of patients.

FundingThis article presents the preliminary results of the project 01 GBA INVESTIGACION SERAM (Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica [Spanish Society of Medical Radiology]) 2015 funded by a SERAM-Industria 2015 grant.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AuthorshipStudy conception: JMJJ, AE, JMSD, MC, GB.

Study design: JMJJ, JMSD, GB.

Data acquisition: JMJJ, AE, JMSD, GB.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: JMJJ, AE, JMSD, GB.

Statistical processing: JMJJ, GB.

Literature search: JMJJ, JMSD, MC, GR, GB.

Drafting of the manuscript: JMJJ, GB.

Critical review of the manuscript with relevant intellectual contributions: JMJJ, AE, JMSD, MC, GR, GB.

Approval of the final version: JMJJ, AE, JMSD, MC, GR, GB.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez Jaso JM, Ezponda A, Muñiz Sáenz-Diez J, Caballeros M, Rábago G, Bastarrika G. Valoración del índice de reserva de perfusión miocárdica por resonancia magnética en pacientes con trasplante cardíaco. Radiología. 2020;62:493–501.