Bowel obstruction is common in emergency departments. Obstruction is more common in the small bowel than in the large bowel. The most common cause is postsurgical adhesions.

Nowadays, bowel obstruction is diagnosed with multidetector computed tomography (MDCT). MDCT studies for suspected bowel obstruction should focus on four points that need to be mentioned in the report: confirming the obstruction, determining whether there is a single transition point or whether the obstruction is found in a closed loop, establishing the cause of the obstruction, and seeking signs of complications.

Identifying signs of ischemia is important in the management of the patient because it enables patients at higher risk of poor outcomes after conservation treatment who could benefit from early surgical intervention to avoid greater morbidity and mortality associated with strangulation and ischemia of the obstructed bowel loop.

La obstrucción intestinal es un proceso frecuente en los servicios de Urgencias de nuestros hospitales, siendo la de intestino delgado más frecuente que la de colon y las bridas posquirúrgicas su causa más habitual.

Actualmente el diagnóstico se realiza mediante tomografía computarizada multidetector, debiendo valorar 4 cuestiones en nuestro informe: confirmar la obstrucción intestinal, determinar si hay un único punto de transición o es una obstrucción en asa cerrada, establecer la causa de la obstrucción y buscar signos de complicación.

La identificación de signos de isquemia es importante en el manejo del paciente ya que permite identificar precozmente aquellos pacientes que no van a evolucionar de forma favorable con el tratamiento conservador y son susceptibles de realizar un tratamiento quirúrgico precoz para evitar la mayor morbimortalidad asociada a la estrangulación y la isquemia del asa obstruida.

Obstruction of the small intestine or colon continues to account for a large number of surgical emergencies treated in Spanish hospitals (20% of acute abdominal symptoms) and is still associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Of these cases, 70% involve obstruction of the small bowel, with post-surgical adhesions being the primary cause1,2.

The other 30% of cases involve obstruction of the colon, with a different aetiology, very often cancerous, and almost always requiring surgical treatment, whether urgent or deferred.

These days, the treatment of small bowel obstruction is mostly conservative, with aspiration through a nasogastric tube and fluid and electrolyte replacement being successful in 70–90% of patients. Treatment with water-soluble oral contrast is sometimes used in patients with persistence of symptoms at 48 h. In general, if the contrast gets through the obstructed area, there is less likelihood of the need for surgery or intestinal resection and of developing complications3,4.

In the 10% of cases which do not respond to this treatment, the risk of complications (ischaemia and necrosis) increases the mortality rate by 20–40%5. In this context, the role of the radiologist is not simply limited to the diagnosis of obstruction, as they also make an essential contribution to the management of the patient, with early identification of those who will not benefit from conservative treatment, in whom urgent surgery will minimise complications and the risk of a fatal outcome6.

Conservative treatment is considered to have failed when the obstruction persists after 72 h, the output from the nasogastric tube exceeds 500 ml on the third day, or when the patient develops signs of peritonitis or ischaemia5.

The symptoms of obstruction are very nonspecific, with abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation and abdominal distension. Laboratory findings and clinical signs suggestive of strangulation include leucocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein and lactate, and signs of peritoneal irritation.

Although used initially, the low sensitivity of plain X-ray, particularly in the diagnosis of ischaemic complications, and the high percentage of false negatives and false positives, have relegated its role, and multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with its very high sensitivity and specificity rates is now the preferred test7.

Analysis of small bowel obstructionThe radiological report needs to establish the diagnosis of bowel obstruction and specify its cause. It should also state whether there are signs pointing to how the patient's condition might progress, informing the surgeon about the likelihood of conservative treatment not being effective, and it should assess the need for early surgical management to avoid morbidity and mortality associated with bowel obstruction-related ischaemia.

We therefore need to answer these four questions5,8:

- 1

Is there a small bowel obstruction?

- 2

Is there a single transition point or is the obstruction in a closed-loop?

- 3

What is the cause of the obstruction?

- 4

Are there signs of complication?

In the diagnosis, we can differentiate between major criteria (necessary for making the diagnosis) and other minor criteria (not necessary, but useful)5,9–11.

Major criteria- -

Identification of small bowel loops dilated more than 2.5−3 cm in diameter, with distal loops of normal lumen.

- -

Point of transition between dilated and non-dilated bowel (excludes paralytic ileus). If there is a gradual narrowing of the lumen, it is called the “beak sign”. Identification of the beak sign is important, not only for diagnosis, but also to determine the aetiology, with coronal and sagittal multiplanar reconstructions being helpful.

When there are not many dilated loops, they can be assessed directly by looking for the site of obstruction, while when there are a large number, retrograde assessment of non-dilated loops is preferable.

We can determine that the cause is an adhesive band by analysing the transition point in different planes. If other causes of obstruction are excluded, there are radiological features that help us detect adhesive bands or “fibro-fatty bands” on MDCT, consisting of identifying the transition point with an associated central area of fat density ("fat notch" sign)11, with which we are able to make the diagnosis of obstruction caused by adhesive bands (Fig. 1).

Bowel obstruction caused by an adhesive band. MDCT image with intravenous contrast in the sagittal plane. The “beak sign” can be seen in two adjacent loops (yellow stars) and the “fat notch sign” (red arrows) on both sides, which should suggest that the cause is an adhesive band (confirmed at surgery).

- -

Air-fluid levels.

- -

Collapsed colon.

- -

Faeces sign10,12 or faecal-like material in the small bowel. Helping us to locate the transition zone, it consists of intestinal material mixed with air in the small bowel and located in the vicinity of the transition zone. It is produced by stasis of the intestinal contents, increased fluid absorption and bacterial overgrowth (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.Small bowel obstruction. MDCT images with intravenous contrast with axial and coronal reconstruction, corresponding to the same patient. Signs of small bowel obstruction, with distension and thickening of the wall of the loops and in some of them the “target sign” (yellow stars) and the “faeces sign” (red arrows). Small amount of free fluid between the loops (green arrow). This patient was treated conservatively and the condition resolved.

It can sometimes also be seen in patients without intestinal obstruction, but combined with dilated proximal loops and collapsed distal loops, it is highly specific for obstruction. The small bowel faecal sign tells us that the function of the wall is maintained and suggests a greater likelihood of it being resolved with conservative treatment10.

Is there a single transition point or is the obstruction in a closed-loop?Closed-loop obstruction occurs when a bowel segment is obstructed at two or more points adjacent to each other, and is isolated from the rest of the intestine. As the contents cannot advance, the secretions increase and the loop dilates and compromises the proximal mesentery, its vessels and the wall, leading to a high risk of ischaemia and making the situation a surgical emergency.

The dilation of the loop and the existence of two nearby stenosis zones make rotation and volvulus of the loop more likely, increasing the risk of ischaemia.

This type of obstruction is mainly caused by adhesions or adhesive bands, or by external and internal hernias and volvulus, with specific signs on MDCT1,2,5,10,13:

- -

Beak sign at the two transition points, which will also be close to each other when there is a single adhesive band or a single hernia orifice.

- -

“C” or “U” configuration of the closed loop, which, depending on its orientation, is seen in one of the three planes (axial, coronal, sagittal).

- -

Wheel sign. This occurs in the case of volvulus, due to torsion of the mesentery, where the dilated loops have a radial arrangement in the plane orthogonal to the axis of rotation, with the vessels converging at the central point, acquiring a characteristic “whirlpool” morphology (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.Bowel obstruction with signs of closed loop and ischaemia. Intravenous contrast-enhanced MDCT images with coronal (A and B), axial (C) and sagittal (D) reconstructions. Distended loops can be seen, some with thin walls and slight minor enhancement of the wall (yellow stars in A and B), mesenteric fluid (green stars in A, B and C) and with the “wheel sign” (images A and B). Loop with thickened wall and free fluid (red arrow) (C). The “beak sign” (white star) and the “fat notch sign” (blue arrow) can be seen (D). This patient with bowel obstruction and signs of closed loop underwent surgery, confirming adhesive band obstruction and necrosis of a long segment of small bowel.

We have to search for the causes of the obstruction in the transition zone. They can be divided into three large groups1,5, which are summarised in Table 1:

Causes of small bowel obstruction.

| Extrinsic | Intrinsic | Intraluminal |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| External |

|

|

| Internal |

| |

|

| |

|

Extrinsic causes

- -

Adhesions/adhesive bands. These are most common cause, the majority due to previous surgery (being less likely after laparoscopic surgery). The rest, occurring in the 10–15% of patients without previous surgery, are usually due to previous peritoneal inflammatory conditions (such as adnexitis), with congenital bands being more rare5,11.

- -

External and internal hernias. External hernias are the second leading cause of obstruction, the most common locations being the inguinal canal and the anterior abdominal wall.

Internal hernias are difficult to diagnose, with 50% being paraduodenal, and it is important to look for suspicious signs such as “clustered loops”, the “whirlpool sign” of the mesenteric vessels, the “mushroom sign” and “abnormally located loops”.

It is very important to consider a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery as a cause of internal hernia (hernias occurring through defects in the mesentery).

The presence of the “whirlpool sign” or tapering of the superior mesenteric vein in patients with a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery indicates an internal hernia (even in the absence of dilated loops)5.

- -

Cancers (extraintestinal).

- -

Endometriosis.

- -

Inflammation. In Crohn's disease we can find stenosis both in the inflammatory-active phase and in the fibrostenotic phase.

- -

Cancers. Primary cancers in the small intestine are rare (the most common are adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumour and gastrointestinal stromal tumour [GIST]).

- -

Mesenteric ischaemia.

- -

Intramural haematoma. A rare cause, this occurs in patients on anticoagulant therapy.

- -

Radiation enteritis. This can develop from two months (acute, due to inflammation) to 30 years (chronic, due to fibrosis) after treatment.

- -

Intussusception. This is a common cause of obstruction in children. In adults, 80–90% have an organic cause (for example, polyps, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma or metastasis).

- -

Gallstone ileus, due to the passage of gallstones into the intestine, with Rigler's triad being typical (obstruction, lithiasis at the transition point and pneumobilia).

- -

Foreign bodies and bezoars. Not common.

Identification of signs of ischaemia3,5,7,10,14,15 is vitally important as it means a very serious clinical situation with increased mortality risk (from 8% to 40%)5 and indicates the need for urgent surgical treatment.

- -

Low uptake or lack of enhancement of the bowel wall. This is the most specific sign with a specificity of almost 95%5, and identification requires comparing it with the enhancement of the adjacent normal loops. The use of dual-energy computed tomography is especially useful in this sign, as it highlights the contrast uptake of the healthy wall and its absence in the ischaemic segment, both when assessing the iodine map and in the low-energy virtual monoenergetic image (KeV), which makes it possible to enhance the difference in density between ischaemic and normal loops2,16,17 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.Signs of ischaemia. A) MDCT image with intravenous contrast and coronal reconstruction. B) MDCT with dual-energy (iodine map) and coronal reconstruction. Patient with already established ischaemia of the loops, with pneumatosis of the wall (red arrow in A), gas in mesenteric vessels and intrahepatic portal veins (yellow star and arrows in A). Less uptake of the wall in the affected loops can be seen (blue star in A and B).

- -

Increase in density of the wall of the ischaemic loop on CT performed without intravenous (IV) contrast. This is a useful sign when IV contrast cannot be administered to perform MDCT due to contraindication. It is produced by intramural haemorrhage as a consequence of venous congestion in the wall of the ischaemic loop and has high specificity for the diagnosis of ischaemia, although low sensitivity18.

It can also be assessed in studies performed with dual-energy MDCT and IV contrast when generating post-processing images without virtual contrast, as it can demonstrate both the hyperdensity of the wall without contrast and the lack of contrast uptake of the loop19,20.

- -

Oedema or mesenteric fluid in the area close to the obstruction. This is the result of oedema of the mesenteric fat due to ischaemia and may be increased by the associated venous congestion. It has been found to practically always be present in ischaemia and its absence tells us the likelihood of ischaemia is very low.

- -

Target sign. Wall thickening greater than 3 mm occurs, due to oedema, haemorrhage or both. It is a non-specific sign as it can have many other causes.

- -

Whirlpool sign. Torsion and congestion of the mesenteric vessels, previously described as an expression of internal hernias and volvulus, and especially in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. It is not very specific because it can be seen in cases of internal hernia without ischaemia and even in other clinical scenarios as an incidental finding.

- -

Free intraperitoneal fluid. This is a very non-specific sign.

- -

Pneumatosis intestinalis. This is the presence of gas in the bowel wall. When found in isolation, it does not always indicate necrosis of the loop wall. It is important to differentiate it from pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (benign process associated with numerous causes in a patient with no clinical signs or laboratory data of severe illness) and pseudopneumatosis (air trapped with faeces and fluid along the bowel wall).

- -

Gas in portal or mesenteric vessels. In the liver it is located peripherally, unlike the central location of pneumobilia.

- -

Pneumoperitoneum, as a sign of mural necrosis and perforation of the wall.

- -

Signs associated with closed-loop obstruction.

Although these signs should make us suspect obstruction complicated by ischaemia, they are often non-specific if considered separately. For that reason, various authors have studied the diagnostic performance of a combination of several of the signs, finding that the association of decreased enhancement of the wall, mesenteric oedema and the presence of various transition zones predict the existence of strangulation and loop ischaemia with a high degree of certainty2,21.

Large bowel obstructionLarge bowel obstruction is less common than small bowel obstruction and differs significantly in terms of aetiology, treatment and prognosis. The most common cause is cancer.

Patients are generally older than in small bowel obstruction. Signs and symptoms are insidious in contrast to the sudden onset of symptoms in small bowel obstruction, with acute colonic obstruction being an abdominal emergency22–24.

The competence of the ileocaecal valve affects the response of the colon. If it is competent, it presents as a “closed-loop” obstruction and, as the caecum is the segment with the largest diameter in the colon, its walls experience higher pressure than the rest (according to the Law of Laplace), which can lead to a diastatic perforation of the caecum. If the valve is incompetent, the colon decompresses in the small intestine and can simulate small bowel obstruction1.

The differential diagnosis is considered with adynamic ileus, Ogilvie's syndrome and toxic megacolon.

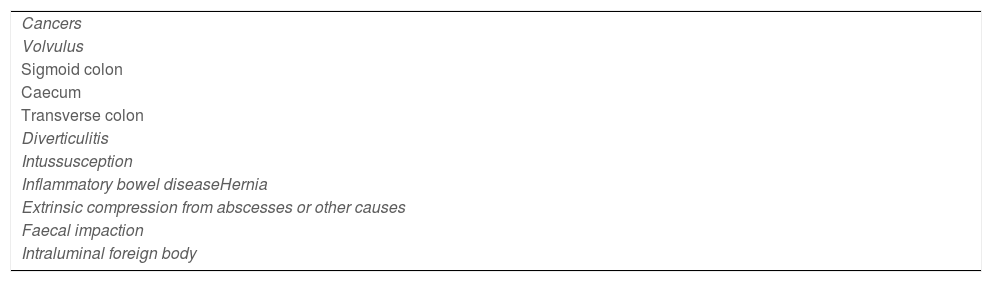

Table 2 shows a summary of the most common causes22:

- -

Cancer. Colon cancer accounts for 60% of cases, most commonly located in the sigmoid colon and the splenic angle of the colon, and the most common site of perforation, the caecum.

- -

Volvulus25. This causes 10–15% of large bowel obstructions. Vascular compromise leads to ischaemia, necrosis and perforation.

Sigmoid volvulus is three to four times more common than caecum volvulus.

The classic signs are the “coffee bean sign”, “beak sign”, inverted-U sign, “northern exposure sign”, specific sign of sigmoid volvulus (location of the sigmoid colon above the transverse colon), and the “whirlpool sign”. Ischaemia findings are similar to those described for small bowel loops.

- -

Acute diverticulitis. The obstruction is caused by oedema of the wall and pericolic inflammation, common in the sigmoid colon.

- -

Intussusception. The most common cause in adults is carcinoma, which acts as the intussusception head.

- -

Hernias. These are less common than in the small bowel and nearly always external.

- -

Inflammatory bowel disease.

- -

Intraluminal obstruction. This is more common in the rectum and sigmoid colon, the most common cause being faecal impaction.

- -

Adhesions, rare in the colon.

- -

Extrinsic compression (endometriosis, lymphadenopathy, peritoneal carcinomatosis).

Bowel obstruction is a relatively common disease in Spanish hospitals, with initial management conservative. Radiologists not only need to diagnose the process and determine its cause, but also inform the surgeon about any signs of complication (closed loop or intestinal ischaemia) which, in conjunction with the clinical and laboratory data (very often non-specific), should point to early surgical treatment and help avoid the higher morbidity and mortality rates associated with these complications.

AuthorshipJesús Gómez Corral, as main author, having collaborated in the preparation and writing of the paper.

Carmen Niño Rojo and Rebeca de la Fuente Olmos in the different sections of the paper.

FundingWe have received no funding from any source.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.