An aortoenteric fistula is an abnormal communication between the aorta and the gastrointestinal tract wall. The high mortality associated with this rare entity means it requires early accurate diagnosis. Aortoenteric fistulas are classified as primary when they develop on a native aorta that has not undergone an intervention and as secondary when they develop after vascular repair surgery.

All radiologists need to be able to recognise the direct and indirect signs that might suggest the presence of an aortoenteric fistula. This article reviews the types of aortoenteric fistulas and their clinical and pathophysiological correlation, as well as the diagnostic algorithm, illustrating the most characteristic findings on multidetector computed tomography.

Una fístula aortoentérica (FAE) es una comunicación aberrante entre la aorta y la pared del tubo digestivo. Se trata de una entidad rara pero con alta mortalidad que requiere, por tanto, un diagnóstico certero y precoz. Se clasifica como primaria si se desarrolla sobre una aorta nativa no intervenida previamente o como secundaria cuando ocurre en un contexto de complicación posquirúrgica de reparación vascular.

Todo radiólogo debería saber reconocer los signos directos e indirectos que pudieran sugerir la existencia de una FAE. En este artículo se revisan los tipos de FAE y su correlación clínico-fisiopatológica, así como el algoritmo diagnóstico exponiendo los hallazgos radiológicos típicos en tomografía computarizada.

An aortoenteric fistula (AEF) is a connection between the aorta and a segment of the digestive tract, generally the third and/or fourth duodenal segment due to the close proximity of the two structures. The second most commonly affected anatomical region is the oesophagus, although cases have also been reported of fistulas connecting the aorta to the stomach, jejunum, ileum or colon.1,2

The first report was made by Sir Astley Cooper in 1829 as an uncommon complication of aortic aneurysm.3 Between then and more recent times, all reported cases arose de novo from an abnormal aorta that had not previously undergone surgery, normally caused by erosion of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. However, as techniques for aortic repair were developed, the incidence of AEF increased as a postoperative complication, and the first case of secondary AEF was reported in 1953 by Brock.4

The reported incidence of primary AEFs ranges from 0.04% to 0.07% of the general population1 and 0.69% to 2.36% of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm5; however, the actual incidence should be higher, since most go unnoticed given their limited associated signs and symptoms. At present, secondary AEFs are more common; their incidence is estimated at 0.3%–1.6% of patients who undergo surgery.6,7 Due to a growing life expectancy and an increasing number of aortic operations, it is presumed that AEF incidence is also increasing; however, it is likely that techniques and endoprosthesis materials are improving simultaneously.

Just as there is a distinctly higher prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms in males versus females, the incidence of AEF is higher in males. The mean age of presentation in primary AEF is 64, whereas patients with secondary AEFs are usually older, around 70.8

AEF has a high out-of-hospital mortality rate; in cases of deaths outside of a hospital setting, the condition is diagnosed post mortem. In the hospital setting, mortality is also high, in part due to limited knowledge of this disease and limited clinical suspicion thereof, which delays diagnosis and suitable surgical management.

ClassificationPathophysiologically, AEFs are classified as primary or secondary.

Primary AEFsIn general, these originate in a context of atherosclerotic disease with eventual development of an abdominal aortic ulcer. However, any disease that triggers chronic inflammation in the aortic wall is also capable of causing a primary AEF. Cases linked to peptic ulcer, neoplasm, radiotherapy, fungal infection and collagen disease have been reported. Tuberculosis and syphilis are other diseases classically considered to be causes of aortitis and AEFs that at present have virtually disappeared in Spain thanks to effective available treatment3; however, in endemic areas such as India, current cases tied to fungal aneurysms in a context of tuberculous aortitis continue to be reported.9 The underlying pathophysiological mechanism is related to the constant pulsatility of the aneurysm against the intestinal wall and a concomitant infectious–inflammatory process with transient bacteraemia, normally Klebsiella or Salmonella.8 This enables microbiological colonisation which weakens the wall of the aorta and results in a fistula.3 A primary aortic fistula may present in a native aorta following ingestion of a foreign body (usually as an aorto-oesophageal fistula.10)

Secondary AEFsThese are more common than primary AEFs and occur as postoperative complications of aortic repair, due either to an abdominal aneurysm or peripheral occlusive disease, although fewer cases in the latter context have been reported. To prevent this complication from developing in open repairs, interposition of the greater omentum between the gastrointestinal tract and the vascular anastomosis is recommended.3 Where a retroperitoneal approach is used, the incidence of AEF is virtually non-existent. The time period ranges from 2 weeks to a decade following the operation.

There was a recent report of a case associated with a prominent anterior vertebral osteophyte that pressed against the proximal vascular anastomosis, thus promoting mechanical erosion; therefore, a detailed description of periaortic structures is necessary in the preoperative vascular evaluation without overlooking degenerative bone proliferation.11

Primary graft infection, as well as the resulting adhesions, play an essential role in the development of secondary fistulas and possibly a more important role than constant pulsatility, understanding AEF to be a natural progression of perigraft infection on a continuous disease spectrum.12 In this case, the main associated micro-organism is Staphylococcus aureus. The point of greatest weakness is found along the suture line, which enables formation of a pseudoaneurysm and subsequent fistulisation. However, there have also been reported cases of secondary AEFs in endovascular repair procedures despite a lack of suturing, which shows that this should not be considered to be a factor sine qua non.13 Infection of the endoprosthesis, migration thereof and presence of endoleaks are fostering elements.14

Moreover, primary gastrointestinal tract surgery may result in a secondary AEF. Cases have been reported of aortogastric fistulisation following Nissen fundoplication, probably associated with phenomena of local ischaemia following ligature of short gastric vessels, direct trauma and postoperative inflammation.15

Clinical manifestations and diagnostic techniquesThe classic triad of gastrointestinal bleeding (haematemesis and/or melaena), abdominal pain and a pulsatile mass is not so common in day-to-day practice.16 Clinical presentation may vary, as explained below:

With manifest bleeding• Haemodynamically unstable: this is a cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with high output, in which there is an open connection to the gastrointestinal lumen. Usually it is preceded by one or more episodes of self-limiting minor bleeding (herald or sentinel bleeding) which present hours to several months before massive acute bleeding.17 These patients should undergo emergency surgery in the form of exploratory laparotomy, since any imaging test would delay treatment and the outcome could be death. Only in cases in which there is no known aneurysm could ultrasound be performed to support a diagnosis of aneurysm (not to study the fistula per se).

• Haemodynamically unstable: in this case, the role of imaging is indeed of vital importance, and computed tomography (CT) is the imaging test of choice. It should be performed as a first-line evaluation (imaging findings are set out in the following section).

- –

Upper endoscopy presents notably low sensitivity (25%–50%)16 due to the difficulty of examining the distal duodenum and identifying the point of bleeding when it is high-flow. In intermittent leaks, endoscopic marking of the visible vessel/blood spots could be performed for subsequent therapeutic management. If spontaneous activation of the coagulation cascade achieves effective haemostasis and subsequent haemodynamic stabilisation, the clinician must exercise caution with endoscopy, since it could promote detachment of the red clot adhered to the duodenal wall that stabilises the ulceration18 (Video 1). Therefore, it is preferable to reserve this method as a second-line diagnostic technique, to rule out other causes of gastrointestinal bleeding. It should be noted that endoscopic findings corresponding to a peptic ulcer are common on a population level, especially in patients with aneurysmal disease,19 such that they could act as confounding factors.

- –

Conventional angiography presents limited sensitivity in cases in which the rate of bleeding is slow; moreover, the high pressure of injection of intravascular contrast could increase the bleeding. At present, angiography takes a back seat to CT, given CT's high availability in emergency departments, short acquisition times and greater diagnostic sensitivity. For the same reasons, magnetic resonance imaging is not considered in the initial diagnostic algorithm. Angiography for confirmation is not required; it is reserved solely for therapeutic percutaneous repair procedures.

In cases in which there is no open connection to the enteric lumen, but there is parietal or graft erosion, signs are more non-specific and include sepsis, malaise and weight loss. This particularly occurs in secondary fistulas, in which there are erosions in the intestinal mucosa which would explain the detection of occult blood in faeces with no clinical repercussions for the patient, who does not perceive any sign of bleeding. Therefore, suspected AEF should be included in the differential diagnosis in patients with a history of aortic surgery who present fever of unknown origin independent of the presence of data suggestive of gastrointestinal bleeding.20,21 Nuclear medicine tests such as scintigraphy with radiolabelled autologous red blood cells are useful for detecting occult bleeding.

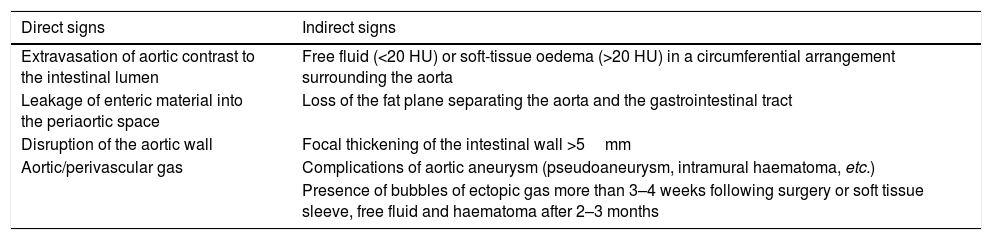

Protocol and imaging findings (Table 1)A CT scan should be performed in all stable patients. The usual protocol includes conducting an evaluation at baseline (collimation 3mm) and following administration of iodinated intravenous contrast (IVC) with acquisition in arterial phases using the bolus tracking technique (collimation 2mm and reconstruction 1mm) and a portal vein evaluation with a delay of 70 seconds (3mm) in a 16+-slice CT scanner.

Direct and indirect signs of aortoenteric fistula on computed tomography.

| Direct signs | Indirect signs |

|---|---|

| Extravasation of aortic contrast to the intestinal lumen | Free fluid (<20 HU) or soft-tissue oedema (>20 HU) in a circumferential arrangement surrounding the aorta |

| Leakage of enteric material into the periaortic space | Loss of the fat plane separating the aorta and the gastrointestinal tract |

| Disruption of the aortic wall | Focal thickening of the intestinal wall >5mm |

| Aortic/perivascular gas | Complications of aortic aneurysm (pseudoaneurysm, intramural haematoma, etc.) |

| Presence of bubbles of ectopic gas more than 3–4 weeks following surgery or soft tissue sleeve, free fluid and haematoma after 2–3 months |

The use of oral contrast should be avoided, since it may obscure intraluminal extravasation.22 It is reserved solely for assessment of dehiscence in postoperative patients.

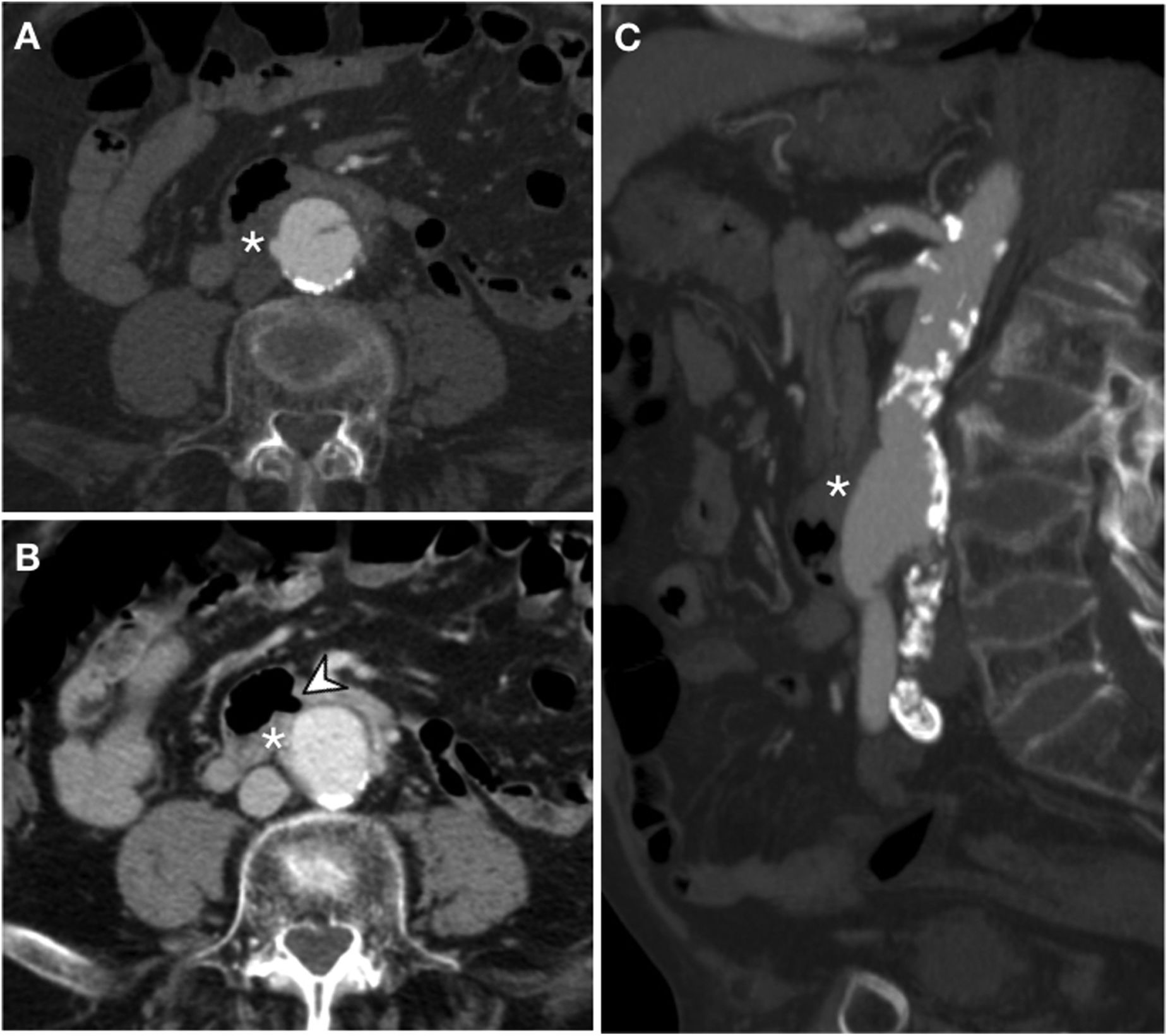

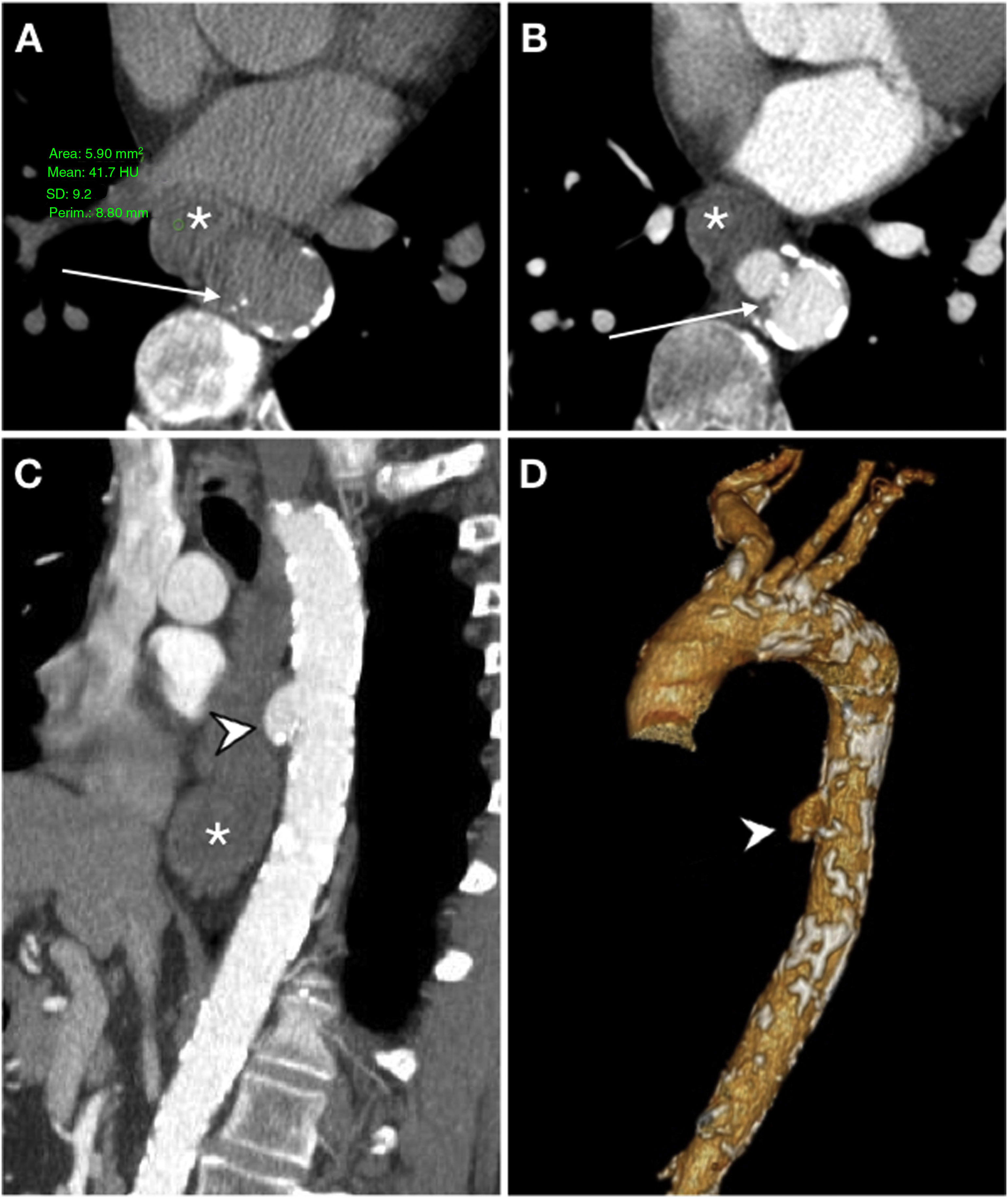

The pathognomonic finding of AEF is active extravasation of aortic contrast towards the patent intestinal lumen in the arterial phase (Video 2, Figs. 1–3). Other highly specific direct findings include leakage of enteric material into the periaortic space and disruption of the aortic wall.12 In addition, the presence of periaortic or intravascular gas (Fig. 4) is highly suggestive of AEF, since aortic infection is normally caused by non–gas-forming micro-organisms.4

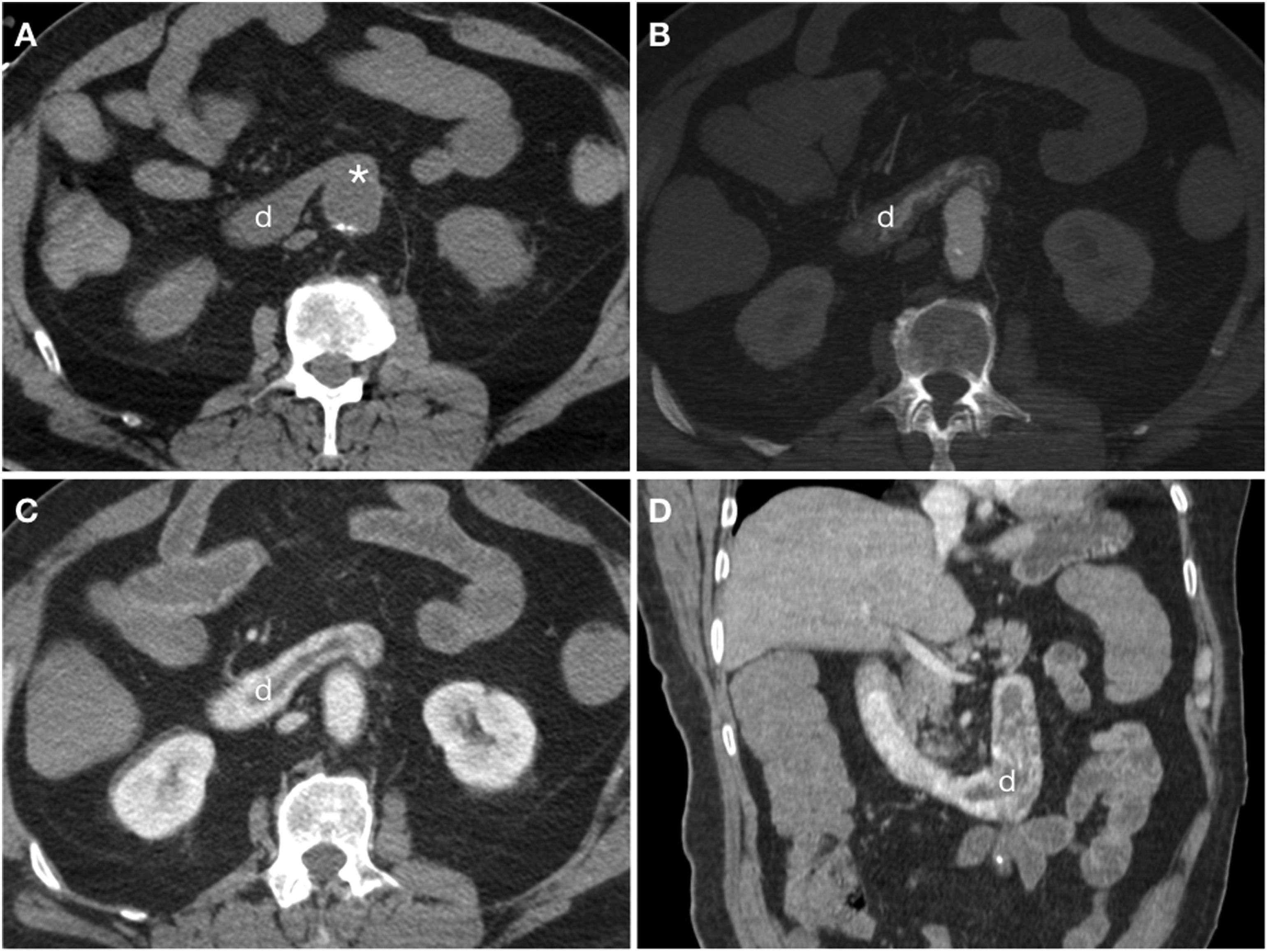

Axial slices from the same patient in Video 2. Computed tomography at baseline (A) and in arterial (B) and portal (C) phases demonstrating loss of the fat plane separating (*) the graft and the third duodenal segment (d) with active extravasation of intravenous contrast towards the duodenal lumen evident from the arterial phase. Reconstruction on the coronal plane (D).

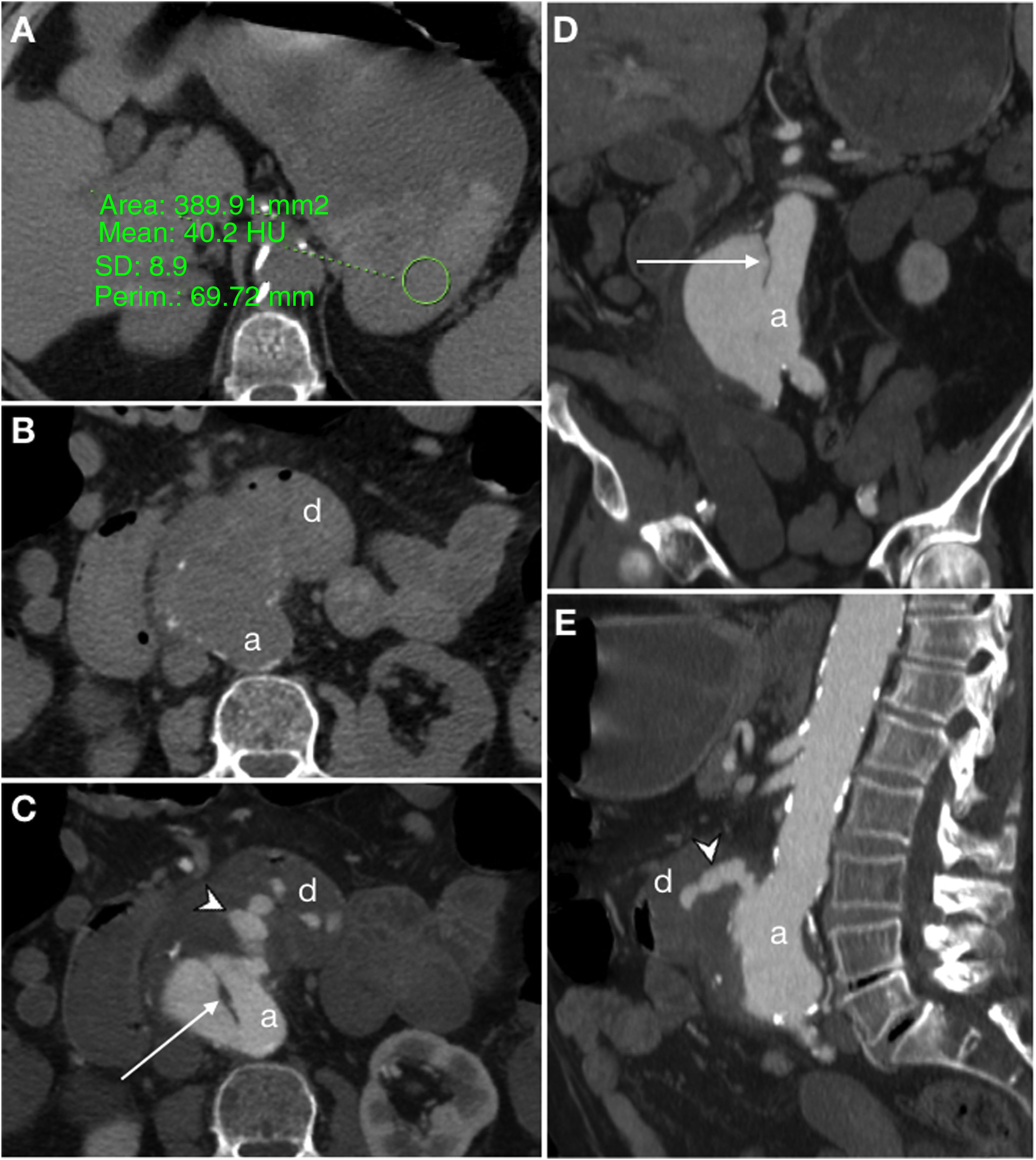

Primary aortoduodenal fistula in a 90-year-old male with haematemesis and severe abdominal pain in a context of acute aortic syndrome. Baseline computed tomography (CT) showed a large clot of 40 HU in the stomach (A) and a calcified aortic aneurysm (a) with loss of the fat plane achieving separation from the duodenal lumen (d) (B). CT with iodinated intravenous contrast (IVC) in the arterial phase (C) showed a penetrating ulcer (arrow) and active extravasation of IVC (arrow tip) towards the duodenum. MIP reconstructions on the coronal (D) and sagittal (E) planes showed the intimomedial flap (arrow) and the jet of IVC (arrow tip).

Secondary aortoenteric fistula in a 77-year-old male with a history of aortobifemoral bypass surgery currently presenting an episode of gastrointestinal bleeding with massive haematochezia, abdominal distension and weak distal pulses. Baseline computed tomography (A), in arterial (B) and portal (C) phases and sagittal MIP reconstruction (D) showed an intimomedial tear (arrow) that affected the anterior surface of the graft in contact with the third segment of the duodenum (d). In addition, extravasation of aortic contrast to the gastrointestinal tract (arrow tip) was observed.

Secondary ileoenteric fistula in a 93-year-old male, with a history of aortobifemoral bypass surgery, who sought care as he presented coffee ground vomitus and melaena. Intravenous contrast was not administered due to a decreased glomerular filtration rate. Craniocaudal slices on the axial plane (A, B and C) of the aortobifemoral bypass (arrow tip) anterior to the native aorta (a) are shown. Figure C identifies intraluminal gas in the right branch of the bypass (arrow) from the immediately adjacent intestinal loop; the native iliac artery is indicated as an anatomical reference (i). Sagittal reconstruction (D) represents the level of the slices.

Sometimes, CT also enables assessment of the aetiology of the fistulisation, for example, by demonstrating the tumour spread of a gastrointestinal carcinoma, usually located in the oesophagus and infiltrating the periaortic fat (Fig. 5).

A 54-year-old male with Barrett's oesophagus who sought care due to signs and symptoms of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with haemodynamic instability. First, an endoscopy was performed which revealed a stenotic lesion in the proximal third of the oesophagus blocking the passage of the endoscope. When the patient experienced another episode of instability, it was decided to perform a computed tomography scan at baseline and following administration of iodinated intravenous contrast (IVC) with biphasic acquisition (only the arterial phase is shown). Axial slice (A) identifying an oesophageal parietal thickening (*) with serous infiltration obliterating the fat plane achieving separation from the aortic arch in relation to tumour spread. MIP reconstructions on axial (B) and sagittal (C-F) planes demonstrated active extravasation of IVC from the aortic arch towards the oesophageal lumen (arrow).

These direct findings present low sensitivity, and indirect signs are more common. These indirect signs consist of periaortic free fluid of low attenuation (<20 HU) or soft-tissue oedema (>20 HU) in a circumferential arrangement surrounding the aorta, loss of the fat plane separating the aorta and the gastrointestinal tract, focal thickening of the intestinal wall (>5mm) and formation of pseudoaneurysms22 (Fig. 6).

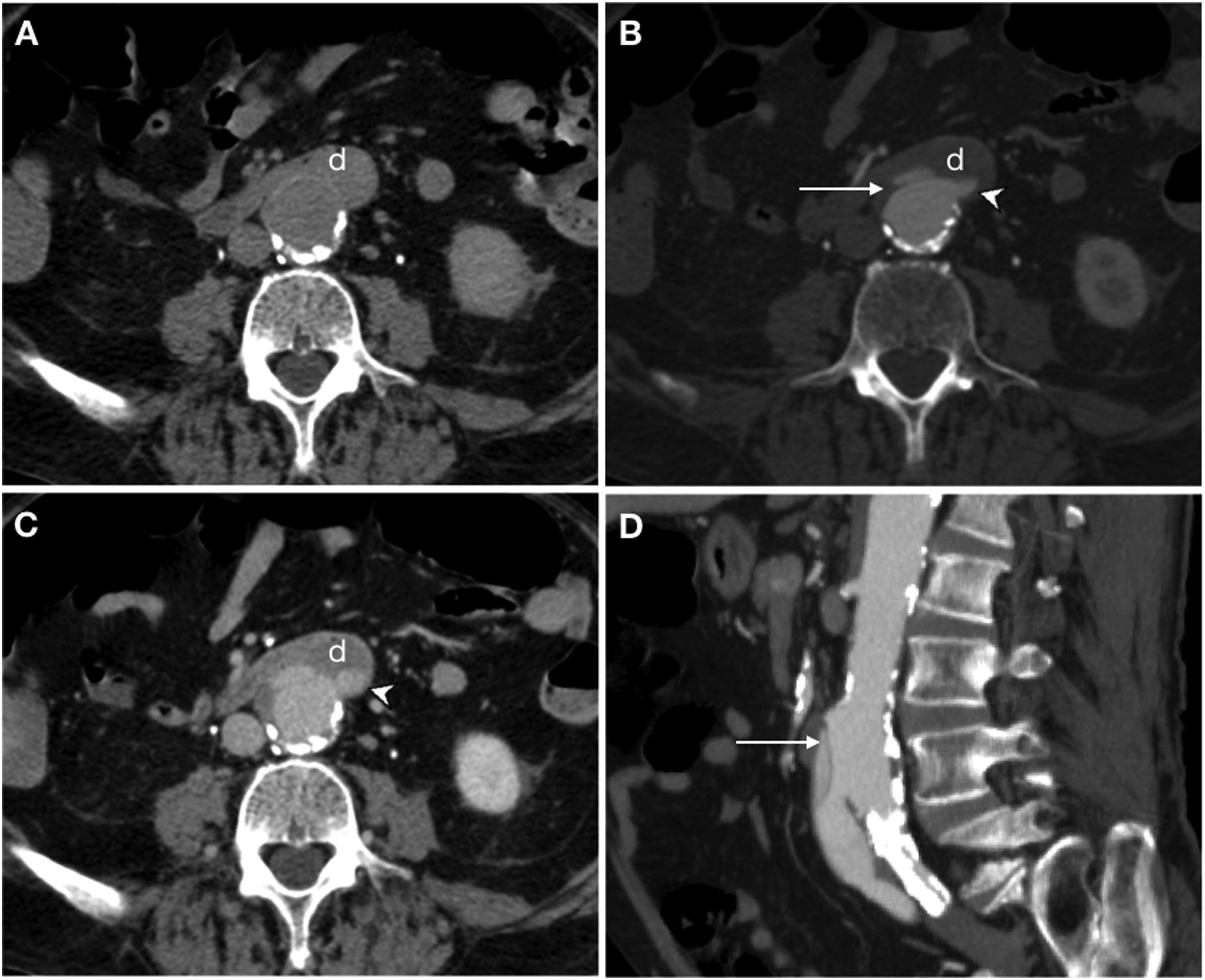

Secondary aortoenteric fistula in a 78-year-old male with a history of aortobifemoral bypass surgery and peptic ulcer disease who sought care due to signs and symptoms of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy revealed an ulceration of the intestinal wall with direct observation of the bypass material. In view of the patient's haemodynamic stability it was decided to assess him by computed tomography. Arterial phase (A), portal phase (B) and MIP reconstruction on the sagittal plane (C). The aortobifemoral bypass was seen to be in intimate contact with the retroperitoneal duodenum presenting a soft-tissue sleeve surrounding the bypass (*) and an ectopic air bubble (arrow tip) with no fat plane for separation. Although active extravasation of IVC was not demonstrated, surgery confirmed the presence of an AEF.

The baseline study is crucial for assessing aneurysm complications that could result in an AEF, such as intramural haematoma and central displacement of intimal calcifications in the penetrating ulcer (Fig. 7). It is also common to identify endoluminal content of high attenuation in relation to red blood cell remnants.

Primary aorto-oesophageal fistula in a 67-year-old male with haematemesis, profuse sweating, skin pallor and hypotension. Baseline computed tomography (A) showed oesophageal dilatation with intraluminal content of high attenuation in relation to a blood component (*) and displacement of intimal calcifications indicating rupture of an atheromatous plaque with an entrance (arrow). The arterial phase on the axial plane (B), sagittal reconstruction (C) and volumetric reconstruction (D) showed calcifications in the wall of the descending aorta and saccular dilatation (arrow tip) in contact with the oesophageal wall with no fat plane achieving separation. These findings suggested a penetrating ulcer. Despite the absence of extravasation of intravenous contrast, the presence of an aortoenteric fistula was confirmed in surgery.

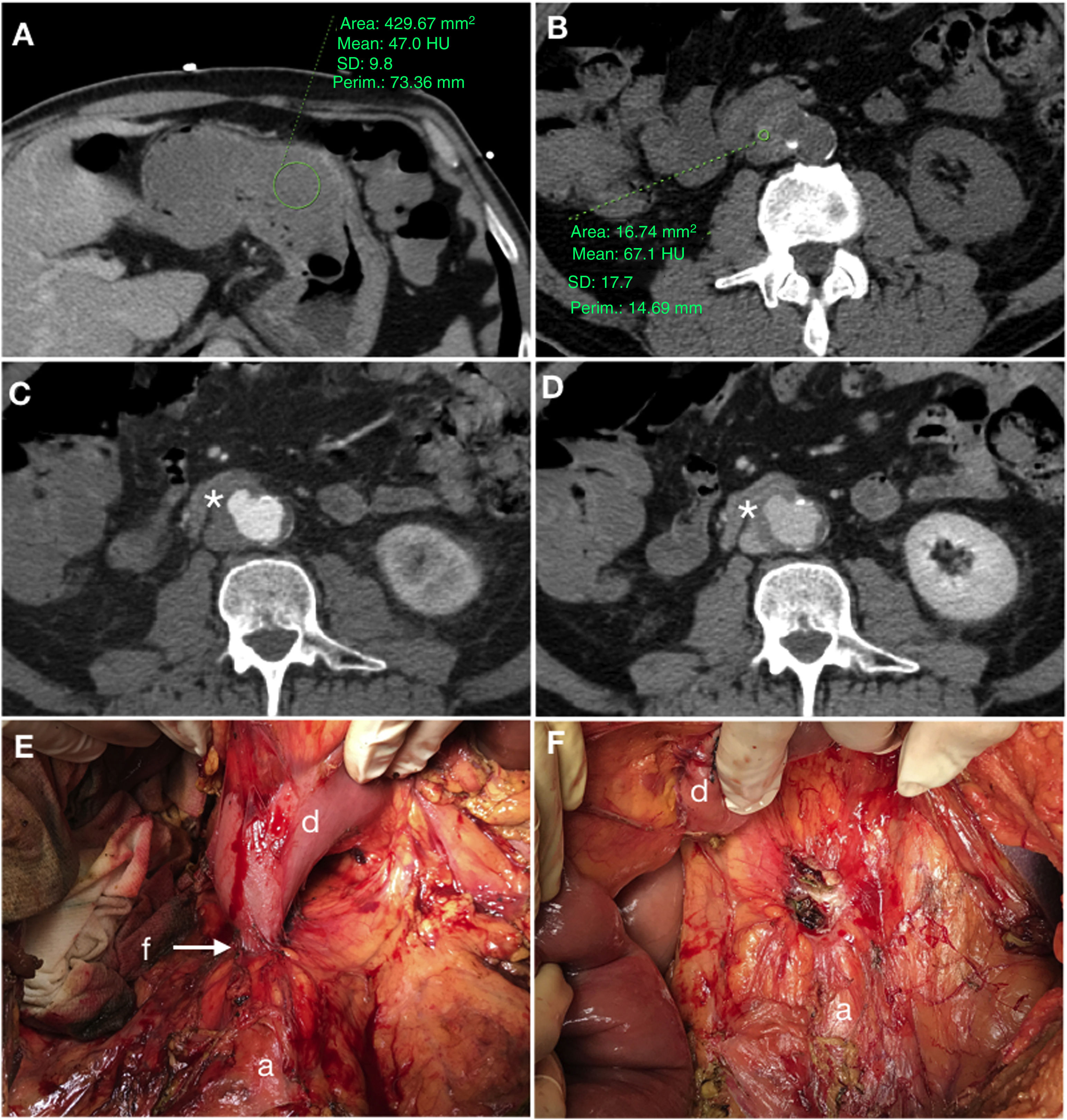

Recently, Kennedy et al. reported the development of a bulge of new onset on the anterior/anterolateral aspect of the aorta in the vicinity of a neighbouring intestinal loop as an early sign of AEF23 (Fig. 8). In the presence of an eccentric thrombus, this finding could be less obvious. However, this was a retrospective study without a control group such that the incidence of this sign in the general population could not be assessed; therefore, it should be assessed with caution.

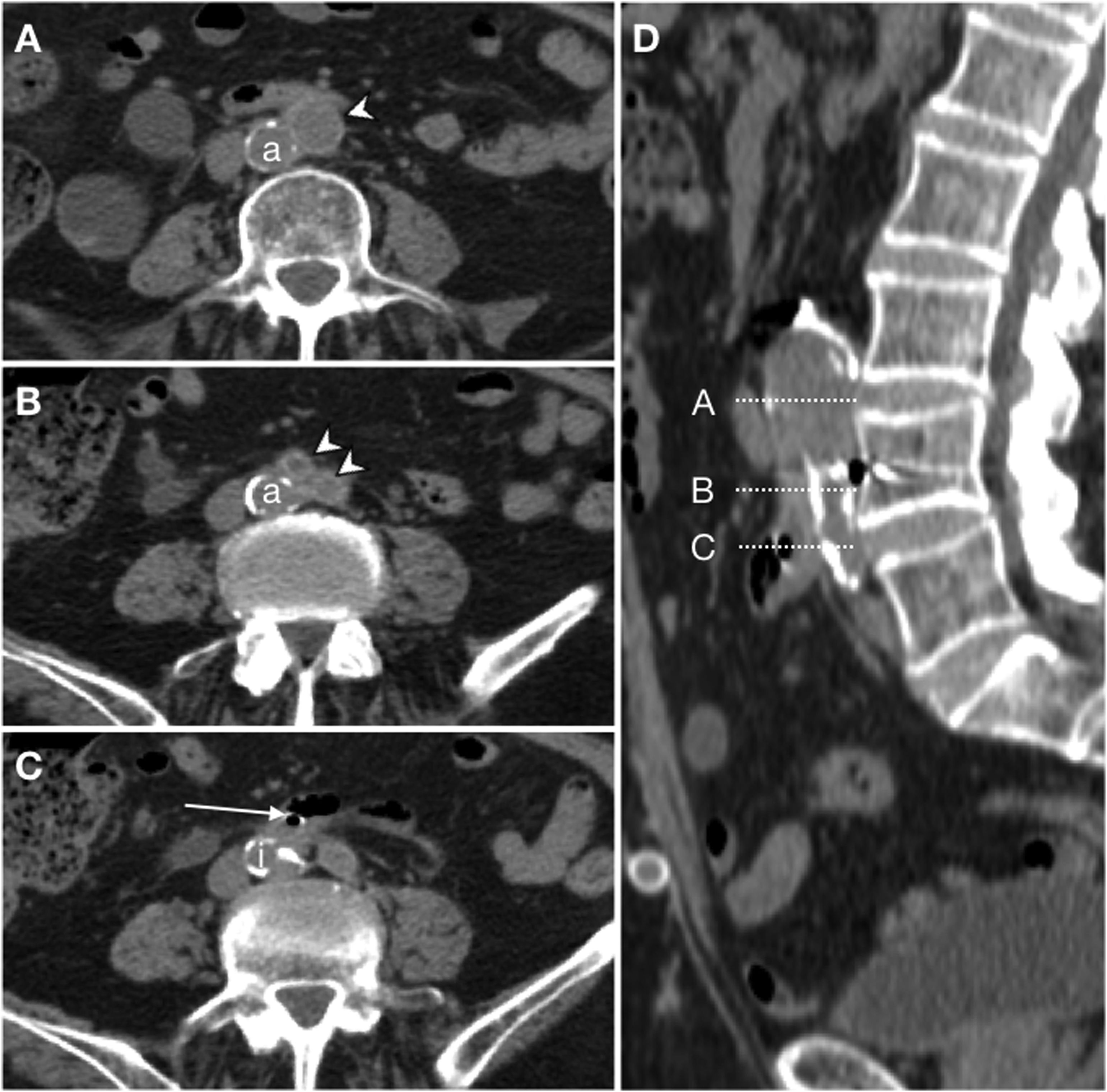

Primary aortoduodenal fistula in a 65-year-old male with an episode of intermittent vomiting and melaena for the past 2 weeks who visited the emergency department with haematemesis, dizziness and hypotension. Baseline computed tomography (A and B) demonstrated high-density (47 HU) content in the gastric chamber in relation to a clot and a calcified aneurysm in the abdominal aorta with an intramural haematoma. The arterial phase (C) revealed a saccular bulge on the anterolateral aspect of the aorta with loss of the fat plane achieving separation with the duodenum (*). The late phase (D) did not demonstrate clear extravasation of IVC. Laparoscopy confirmed the presence of an AEF (E) (a: aorta; d: duodenum; f: fistula) which was repaired in the same surgical procedure (F) including segmental resection of the duodenum.

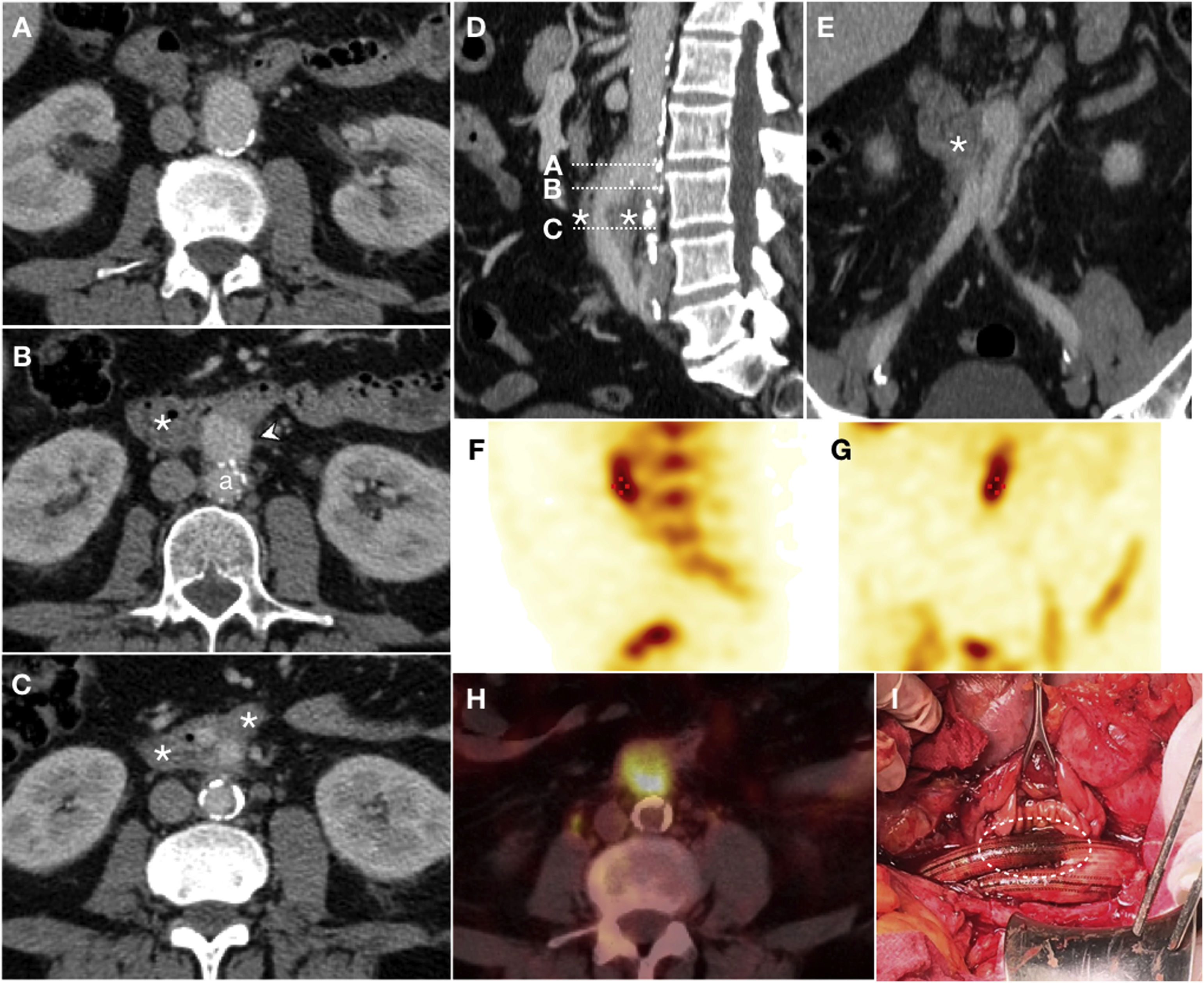

In secondary AEF, it should also be borne in mind that bubbles of ectopic gas more than 3–4 weeks following surgery are an abnormal finding in a postoperative context and the radiologist should be alerted. Analogously, thickening of attenuation in soft tissues, free fluid and postoperative haematoma should resolve in 2–3 months following surgery.21

If what is suspected is graft erosion in a context of secondary AEF, nuclear medicine techniques such as 18F-FDG PET/CT and SPECT with marked leukocytes may be very useful for detecting perigraft infection22 (Fig. 9). Demonstrating the presence of fistulisation in the absence of specific signs is a true diagnostic challenge, as infection findings overlap with AEF findings. In precisely these cases, scintigraphy with red blood cells could be useful.

Graft erosion in a 61-year-old male with a history of aortobifemoral bypass surgery who presented long-standing fever, chills, weakness and persistent bacteraemia. Due to suspicion of graft infection, a CT scan was performed with IVC in the portal phase (A–C) which revealed perigraft oedema and parietal thickening of the third segment of the duodenum (*) encompassing the right iliac branch of the bypass in the absence of a fat plane achieving separation. Sagittal reconstruction (D) represented the level of the axial slices and coronal reconstruction (E) supported the findings reported. Extravasation of IVC was not observed. SPECT with marked leukocytes (F, G) showed radiotracer accumulation, and a PET/CT scan (H) revealed an increase in metabolic activity in the region proximal to the graft. These findings were suggestive of infection. Surgery (I) demonstrated the presence of graft erosion (dashed ellipse).

An AEF is a rare but very serious condition in which patient survival requires an accurate and early diagnosis. Primary AEFs usually occur in patients who seek care for signs and symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with a complicated abdominal aortic aneurysm. Secondary AEFS, which are much more common, occur in patients with prior surgery on the aorta, and the spectrum of presentation ranges from massive bleeding due to an open connection to the enteric lumen to more latent clinical forms due to graft erosion, in which case bleeding is of lesser significance. It would be a mistake to think that an AEF is unequivocally associated with manifest bleeding, since it may present as sepsis, malaise or weight loss (perigraft/AEF infection continuum).

CT is essential for making a precise diagnosis. The absence of extravasation of intravenous contrast or periaortic/periprosthetic ectopic gas does not rule out the diagnosis of AEF, since they are direct signs with high specificity but low sensitivity. The loss of the fat plane that achieves separation (in surgery the omentum is positioned to this end) with focal thickening of the intestinal wall, free fluid and/or oedema of the periaortic/periprosthetic tissues are findings that should concern the radiologist in the appropriate clinical context.

In suspected infection of an aortic prosthesis, the presence of fistulisation cannot always be determined, in which case nuclear medicine tests could be useful.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Nagrani Chellaram S, Martínez Chamorro E, Borruel Nacenta S, Ibáñez Sanz L, Alcalá-Galiano A. Fístula aortoentérica: Espectro de hallazgos en tomografía computarizada multidetector. Radiología. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2020.01.010