Suplement “Update and good practice in the contrast media uses”

More infoRadiological contrast media, both iodinated and gadolinium-based, can lead to adverse reactions. Type A reactions are related to the pharmacological characteristics of the contrast, including side, secondary and toxic effects. Post-contrast acute kidney injury is the most frequent adverse reaction to iodinated contrast media. Less frequently, thyroid, neurological, cardiovascular, haematological, and salivary gland effects are also detected. With gadolinium-based contrast agents, nausea is the most frequent reaction, but there is also a risk of producing nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and cerebral deposits of uncertain significance.

The most effective way of avoiding type A reactions is to decrease the dose and frequency of contrast media administration, especially in patients with pre-existing renal insufficiency. To prevent post-contrast acute kidney injury, adequate hydration of the patient should be maintained orally or intravenously, avoiding prolonged periods of liquid fasting.

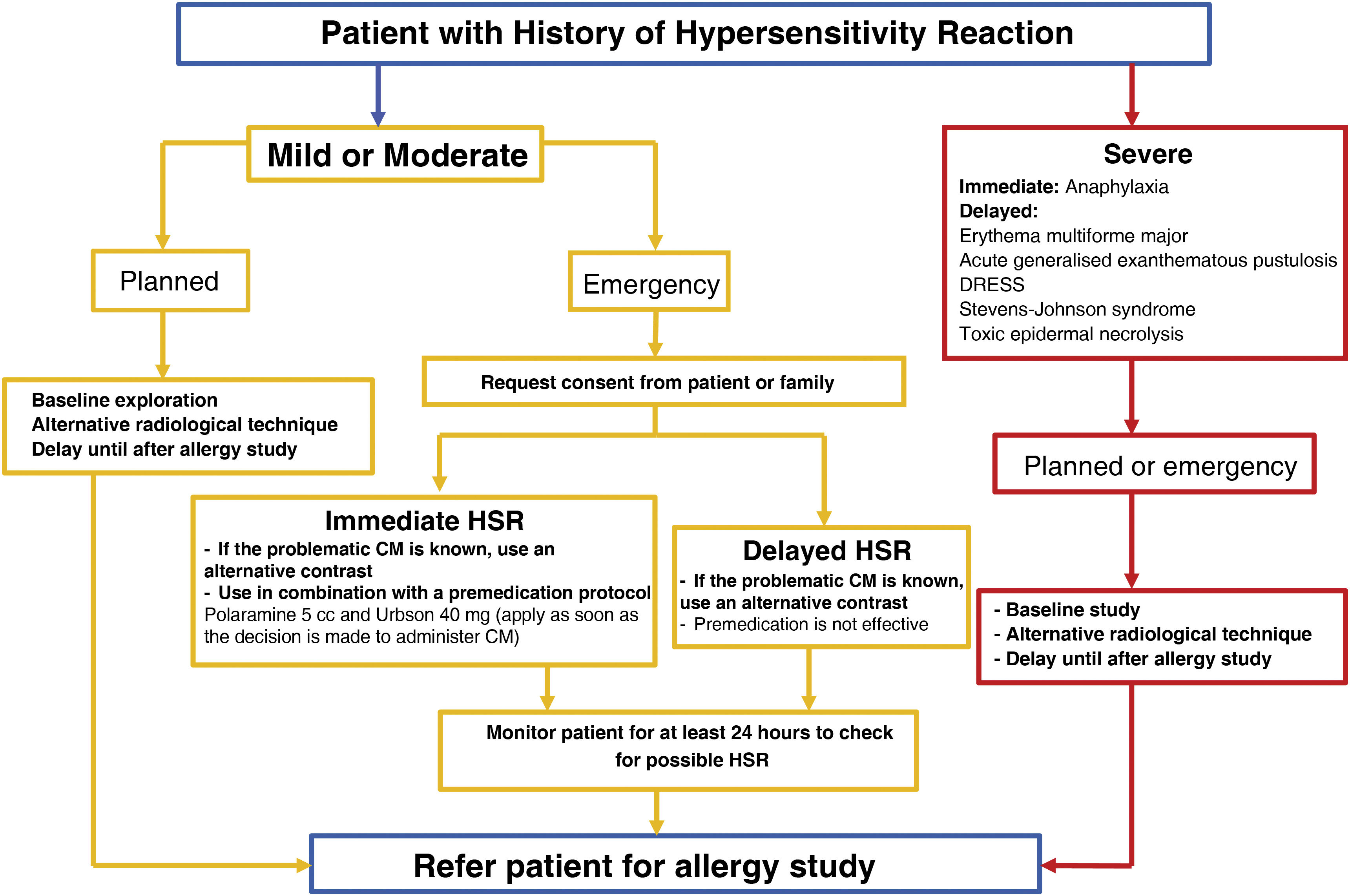

On the other hand, hypersensitivity reactions are dose-independent and clinically can range from mild cutaneous reactions to anaphylaxis. This article proposes an algorithm that differentiates between nonspecific reactions and true hypersensitivity reactions, as well as levels of severity. It also provides a treatment scheme for immediate reactions adjusted to the severity level, with a focus on the management of anaphylaxis and an early intramuscular administration of adrenaline. Finally, it sets out recommendations for the management of patients with previous hypersensitivity reactions who require elective or urgent contrast administration, favouring the use of alternative contrast media with confirmed tolerance instead of the indiscriminate use of premedication.

Los medios de contraste radiológicos, tanto los yodados como los de gadolinio pueden inducir reacciones adversas. Las reacciones tipo A están relacionadas con las características farmacológicas del contraste, incluyendo los efectos colaterales, los secundarios y los tóxicos. En el caso de los contrastes yodados, la lesión renal aguda post-contraste es la afectación más frecuente. Con menor frecuencia se pueden inducir efectos a nivel tiroideo, neurológico, cardiovascular, hematológico y de glándula salivares. Con los contrastes de gadolinio la reacción más frecuente es la aparición de náuseas, existiendo riesgo de producir fibrosis sistémica nefrogénica y depósitos cerebrales de significado incierto.

La medida más eficaz para evitar las reacciones tipo A es disminuir la dosis y la frecuencia de administración del contraste, especialmente en pacientes con insuficiencia renal previa. Para prevenir la lesión renal aguda post-contraste debemos mantener una hidratación adecuada del paciente por vía oral o parenteral, evitando periodos de ayuno de líquidos prolongados.

Por otra parte, las reacciones de hipersensibilidad son independientes de dosis y clínicamente pueden presentarse desde un cuadro cutáneo leve hasta una anafilaxia. En el artículo se propone un algoritmo que permitiría diferenciar una reacción inespecífica de una verdadera reacción de hipersensibilidad, así como identificar su gravedad. Asimismo, se plantea un esquema de tratamiento de las reacciones inmediatas ajustado al nivel de gravedad, incidiendo en el manejo de la anafilaxia y la administración precoz de adrenalina intramuscular. Finalmente, se detallan recomendaciones sobre el manejo de los pacientes con reacciones de hipersensibilidad previa que precisan la administración de un contraste de forma electiva o urgente, favoreciendo el uso de contrastes alternativos con tolerancia confirmada en lugar del uso indiscriminado de la premedicación.

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) describes any undesirable response to a drug that has been administered at a normal dose to prevent, diagnose or treat a disease, or modify a physiological function.

Rawlins et al. proposed an A/B classification to differentiate between two types of ADR according to their symptomatology, pathogenesis, prognosis and prophylaxis (Table 1).

Classification of adverse drug reactions.

| Adverse drug reactions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type A reactions | Side effects | Undesirable pharmacological effect of the medication | |

| Secondary effect | Caused by the drug's effect, but usual | ||

| Toxic effect | Produced by excessive drug concentration | ||

| Type B reactions (hypersensitivity reactions) | According to the moment that symptoms appear | Immediate hypersensitivity reactions (IHSRs) | These appear as soon as the drug is administered |

| Delayed hypersensitivity reactions (DHSRs) | These appear at least one hour after the drug is administered | ||

| According to the pathogenetic mechanism | Allergy-like HSRs: adaptive immunity intervenes | In IHSRs: Immunoglobulins (IgE, and less frequently IgG)In DHSRs: cellular response (lymphocytes, eosinophils, etc.) | |

| Non-allergy-like HSRs: innate immunity intervenesEspecially in IHSRs. | Involved complement system, coagulation, bradykinin, vascular factors, mast cell receptors (MRGPRX2, etc.) | ||

DHSR: delayed hypersensitivity reaction; HSR: hypersensitivity reaction; Ig: Immunoglobulin; IHSR: immediate hypersensitivity reaction; MRGPRX2: Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor member X2.

Type A ADRs (augmented): Most common type of ADR, predictable, related to the drug’s intended pharmacological mechanism, and dose-dependent. With low rates of mortality and high rates of morbidity, the most effective preventative measure is dose reduction. Within this group, we further differentiate between:

- -

Side effects: reaction unintended but in line with the drug’s pharmacological effect.

- -

Secondary effects: reaction caused by a drug’s main effect but is not usual.

- -

Toxic effects: reaction caused by high concentration of the drug. This is usually attributed to an excessive dose but may also occur due to characteristics of the patient that produce an increased response to an appropriate dose, such as genetics, age, pregnancy or concomitant illness.

Type B ADRs (idiosyncratic): reactions unrelated to the pharmacological effects of the drug, unpredictable and rarely dose-dependent. Can occur in response to small quantities of the drug. Includes hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) to a drug. Type B ADRs arise due to the characteristics of the patient receiving the drug, as the patient has an adverse reaction even though the formulation and dosage are appropriate. HSRs are classified according to the time of symptom onset and the pathogenic mechanism, both of which are valuable for proper diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

This article will review the management of ADRs to iodinated contrast media (ICM) and gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs), with currently available formulations listed in Table 2. The main objective of this article is to update readers on type A reactions to both types of radiological contrast media (CM), and more extensively on HSRs, proposing algorithms for appropriate diagnosis, severity assessment and treatment. We also propose recommendations for the management of patients who have previously suffered HSRs.

Classification of iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast media.

| Group | Iodinated contrast media | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Active ingredient | Commercial name | Osmolality | |

| Ionic monomer | Meglumine and sodium diatrizoate | Plenigraf©Pielograf© | >1600 mOsm/kg |

| Meglumine amidotrizoate | Radialar©Uro Angiografin© | ||

| Sodium amidotrizoate and amidotrizoate meglumine | Gastrografin©Gastrolux©Trazograf© | ||

| Iopanoic acid | Colegraf© | ||

| Ionic dimer | Ioxaglate | Hexabrix© | 600 mOsm/kg |

| Iotroxic acid | Bilisegrol© | ≈600 mOsm/kg | |

| Non-ionic monomer | Iohexol | Omnipaque© | 322–844 mOsm/kg |

| Ioversol | Optiray© | 502–792 mOsm/kg | |

| Iomeprol | Iomeron© | 726 mOsm/kg | |

| Iopamidol | Iopamiron© | 524–796 mOsm/kg | |

| Iopromide | Ultravist© | 328–774 mOsm/kg | |

| Iobitridol | Xenetix© | 915 mOsm/kg | |

| Ioxilan | Oxilan© | <350 mOsm/kg | |

| Iopentol | Imagopaque© | <1000 mOsm/kg | |

| Non-ionic dimer | Iodixanol | Visipaque© | 270–320 mOsm/kg |

| Iotrolan | Isovist© | ≈300 mOsm/kg | |

| Gadolinium-based contrast media | |||

| Linear ionic | Gadopentetate dimeglumine | Magnevist© | |

| Gadobenate dimeglumine | Multihance© | ||

| Gadoxetate disodium | Primovist© | ||

| Linear non-ionic | Gadodiamide | Omniscan© | |

| Macrocyclic ionic | Gadoterate meglumine | Dotarem© | |

| Macrocyclic non-ionic | Gadoteridol | Prohance© | |

| Gadobutrol | Gadovist© | ||

| Gadopiclenol | Elucirem© | ||

Typical characteristics and frequency of reactions are described in the product documentation of the ICM. They are more prevalent with ionic ICM than with non-ionic ICM, ranging between 33.8–12.7% and 0.7–3.1%, respectively.

Kidneys: post-contrast acute kidney injuryThe most common type A ADRs to ICM, with an incidence of less than 2% in patients with normal renal function, but higher in patients with pre-existing renal impairment. Depending on the type of ICM used, incidence ranges between 5–12% for high-osmolar agents and 1–3% for low-osmolar agents. It is more common with ionic agents (3.8–12.7%) than with non-ionic agents (<3%).1

No significant benefit is thought to be gained by switching from a low-osmolar to an iso-osmolar ICM. Rather, the most appropriate measures to reduce the risk of developing this kind of kidney injury involve reducing the amount of ICM administered and ensuring adequate hydration of the patient.2

CardiovascularICM can produce arrhythmias by altering the cardiac conduction system and decreasing myocardial contractility.3

HaemotologicalICM cause a slight decrease in haematocrit and morphological changes in red blood cells, both in shape and plasticity, as well as platelet alterations that do not produce any clinical effects; however, corticosteroids or platelet transfusion may be required occasionally.4

The intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways may also be affected, directly causing a reversible inhibition of thrombin production which increases bleeding time and inhibits fibrinolysis.5

NeurologicalA wide spectrum of symptoms can manifest which are usually mild, such as vomiting, headaches or vasovagal syncope. However, contrast-induced encephalopathy can also occur, which is usually transient and does not need treatment. The most common presentation of encephalopathy is cortical blindness, but there have also been reports of aphasia, hemiparesis, parkinsonism, aseptic meningitis and seizures.6

ThyroidsToxic effects on the thyroids are due to the free iodine present in all ICM vials (50 g/ml), which increases during product storage. In addition to the free iodine in the vials, iodine is released during the deiodination processes of the ICM molecules when they are metabolised in the body after administration.

In healthy subjects, there are no significant changes in total thyroxine (T4) levels after ICM administration, but in older adults and children, subclinical hyperthyroidism with increased free T4 and decreased thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels may occur, self-limiting in most cases.7

By contrast, patients with a history of thyroid disorder may develop an episode of hyperthyroidism, which is usually self-limiting, resolving within a few weeks after exposure. This abnormality is more common when the patient has also suffered from Graves' disease, but it can also occur in multinodular goitre.8

Salivary glands (post-contrast sialoadenitis)Salivary glands concentrate 30–100 times more iodine than plasma, so any increase in its bioavailability has an impact on its glandular concentration. After an ICM is administered, it can accumulate in the salivary ductal mucosa, inducing inflammation with obstruction of the ducts and enlargement of the affected glands, usually the submandibular glands.9 Clinically, the patient presents with swelling in the affected glandular area, together with mild inflammatory symptoms (erythema, oedema, pain). It usually resolves with no further incidents within a few days.

Type A adverse drug reactions to gadolinium-based contrast agentsNausea or vomitingThe feeling of nausea comes on quickly and is often very intense, but usually subsides quickly without vomiting. Treatment is not usually necessary.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosisA condition characterised by the progressive and irreversible generalised fibrosis of the skin and some internal organs. Patients present with sclerosis-like skin, joint disorders and, especially, severe nephrological impairment progressing to end-stage kidney disease. It is considered an ADR due to the toxic action of gadolinium ions dissociated from their chelating agent, this effect being more intense with linear GBCAs. Thereby, the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products (AEMPS) issued a statement in 2009 recommending the prioritisation of macrocyclic GBCAs.10

Cerebral depositsIn 2014, gadolinium deposits were identified in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus, and later in other structures of the central nervous system (CNS) too. These deposits appear more with linear GBCAs than with macrocyclic GBCAs. Their clinical impact has not been confirmed, but there have been reported associations with non-specific neurological symptoms such as paraesthesia, tingling and mental confusion.

Based on this information, the AEMPS made a recommendation in 2017 to avoid the use of linear GBCAs (with the exception of gadoxetic acid in patients with poorly vascularised liver lesions), prioritising the use of macrocyclic GBCAs, at the lowest possible dose.11

Prevention of type A adverse drug reactions to contrast mediaThe following recommendations on prevention are included in different radiology guidelines, including those of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR)12 and the American College of Radiology (ACR).13 As Type A ADRs are dose-dependent pharmacological reactions, the most effective recommendation is to reduce the dose administered and to avoid repeated doses. In general, if the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) >30 ml/min/1.73 m2, the interval between doses of ICM, an GBCA or a combination of the two shall be at least four hours. However, in patients with lower GFRs, the interval between doses should be 48 h for ICM and seven days for GBCAs.

Concerning ICM, the general consensus is that their administration is not contraindicated by the presence of concomitant diseases such as pheochromocytoma, multiple myeloma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Furthermore, hyperthyroidism is not a contraindication, except when patients have acute thyroid storm or if they are currently undergoing treatment with radioactive iodine. No medications should be interrupted, not even metformin.

With regard to post-contrast acute kidney injury, in addition to dose reduction, the most effective measure is adequate hydration. This should be carried out routinely, but it is especially important for those patients at higher risk, namely those with a GFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2 when contrast is administered intravenously, and <45 ml/min/1.73 m2 when contrast is to be administered intra-arterially. Oral hydration is considered to be as effective as parenteral hydration, so prior to an imaging examination, fluids should not be avoided for longer than the two hours.

Regarding GBCAs, since previous renal failure is the greatest risk factor for inducing nephrogenic systemic nephrosis, it is appropriate to choose a safer alternative for patients with a GFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2, such as a non-contrast MRI or an alternative scan.

Type B reactions to radiological contrast mediaThe term ‘hypersensitivity’ is recommended for all reactions to contrast media that are not of type A or that are non-specific, reserving the term ‘allergic’ for those HSRs in which adaptive immunity is recognised as a fundamental part of their pathogenesis.

The overall incidence of HSRs to ICM is less than 5% of patients undergoing radiological studies with ICM,14 having decreased, both in frequency and severity, with the use of low-osmolar agents,15 namely 0.16–12.66% for ionic agents and 0.03–3% for non-ionic agents.16 With regard to the severity of HSRs, 70% of cases are mild, 20–27% are moderate and less than 3% are severe,14 with an estimated death rate of one per one million cases.17

Concerning GCMs, the incidence of HSRs is less than 0.1%.18 Innate and adaptive immunity mechanisms may intervene, including activation through interaction with the Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor member X2 (MRGPRX2).19 Immediate reactions are more common, especially urticaria (50–90% of cases), and only a small percentage experience anaphylaxis (0.004%–0.01%).20 Occasionally, mild cases of delayed onset are reported.21

Immediate HSRs (IHSRs) begin while the individual is still in the diagnostic radiology department, and in most cases, resolve quickly if treated appropriately. Symptoms most commonly affect the skin,22 with a localised or generalised red itchy rash. It may also be accompanied by angioedema, and less frequently, by isolated erythema or a maculopapular rash. More generalised skin involvement, with angioedema or facial involvement, does not mean that the HSR is more severe. Rather, the following symptoms suggest anaphylaxis: a sensation of pharyngeal obstruction, dysphagia, dysphonia, persistent cough, wheezing dyspnoea, digestive symptoms, low blood pressure or cardiorespiratory arrest. It is important to note that anaphylaxis can also occur without any associated cutaneous symptoms.

As IHSRs develop, the mast cell is the leading cell. Innate immune mechanisms may play a role in mast cell activation, including stimulation of mast cell receptors such as MRGPRX2.23 On the other hand, it may be mediated by adaptive immunity through the formation of specific Immunoglobulin E (IgE) that recognises the CM,20,24 and this would be a true allergic type of IHSR.

Delayed HSRs (DHSRs) are usually mild skin events that occur in the first hours or days after CM administration.21,25 Manifestations commonly involve a maculopapular rash, and sometimes late-onset urticarial.14,26 Reactions are usually mild or moderate in severity, resolving in under a week either spontaneously or after treatment with corticosteroids and antihistamines.27 More severe DHSRs are rare, with the following signs signalling risk: haemorrhagic or erosive lesions, vesicles, skin disruption, mucosal involvement or systemic symptoms (fever, renal or hepatic impairment, lymphadenopathy). This group includes erythema multiforme major, cutaneous vasculitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis, toxic epidermal necrolysis and drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).28

Adaptive immunity mechanisms are involved in DHSRs, especially lymphocyte and eosinophilic cellular responses29 and therefore in most cases, we could speak of allergic HSRs. Its incidence has increased with the use of non-ionic ICMs, ranging from 0.1 to 9.5%,30 and especially with dimeric ICMs such as iodixanol.31 The actual incidence is probably higher, as many cases are not counted given that symptoms appear when patients have already left the examination room.32

Radiologist's response to a hypersensitivity reaction to radiological contrast mediaIn this section we will follow the algorithm proposed in Fig. 1, focusing on IHSRs, as these are the type that radiologists will have to handle in the examination room.

When symptoms first appear, we must determine whether we are dealing with a true IHSR. Patients frequently report facial flushing, genital itching, warmth, nausea, metallic taste, or even dizziness with low blood pressure and bradycardia during or immediately after ICM administration. These symptoms are usually mild, transient and resolve spontaneously, but they can alter the performance of a radiological technique. In addition, they can be difficult to differentiate from true HSRs, and as a result, some subjects may be erroneously labelled as allergic to ICM.33 If there is uncertainty around whether symptoms are non-specific, it is always advisable to treat the situation as a true IHSR.

Once an IHSR has been confirmed, we must categorise its severity. In radiology, we usually use the ACR classification to categorise severity,13 but its criteria diverge from other commonly used standards such as the severity classification used in allergology. For example, ACR classifies generalised cutaneous manifestations or facial oedema with no other associated symptoms as moderate HSRs, whereas in allergology they would be considered mild HSRs. The most commonly used severity scales in allergology are the Ring-Messmer34 or Brown35 scales, both of which are more closely aligned with the prognosis, morbidity and mortality of IHSRs. We have developed a severity assessment algorithm (Fig. 1) following the recommendations of the 2022 GALAXIA guidelines (concerning anaphylaxis, drawn up by the Spanish Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology [SEAIC]).36 They propose clear criteria to differentiate between a mild or moderate reaction and anaphylaxis, as the latter requires more rapid and aggressive treatment due to its morbidity and mortality rates.

Once the severity of the IHSR has been established, treatment should be promptly initiated in line with the level of severity (Fig. 2). In mild and moderate IHSRs, treatment consists of antihistamines and corticosteroids.37 To accelerate their therapeutic effect, they can be administered intramuscularly, or intravascularly via the venous access used to administer the CM, and in some cases, they can also be administered orally. If symptoms persist, antihistamines and corticosteroids may be repeated every six to eight hours until symptoms are under control. If the patient responds effectively, they can be discharged with treatment continuing at home with a second generation oral antihistamine until symptoms are under control. It is advisable to add a short course of oral corticosteroids for five days (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/day) if there are moderate symptoms.38–40 If, however, the patient's evolution is unsatisfactory, they should be referred to a hospital emergency department for follow-up.

If a patient suffers an anaphylactic-type reaction, appropriate measures must be taken urgently. The treatment of choice for anaphylaxis is the administration of intramuscular adrenaline,41 the dose of which is adjusted according to weight and age. This should be administered promptly, and it may be repeated every five to 15 min in the case of refractory symptoms.42 Intravenous adrenaline should only be administered by experienced medical staff, in a hospital setting and with close cardiac monitoring. In the event of cardiorespiratory arrest, standardised cardiopulmonary resuscitation manoeuvres should be performed. There are no absolute contraindications for the use of adrenaline, as the risks of its inappropriate use outweigh the possible adverse effects of its administration.43 But we should be aware that patients with cardiovascular comorbidities, hypertension or hyperthyroidism, or those being treated with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants or beta-blockers are at higher risk of adverse effects.

These patients should be monitored early (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation [sO2], electrocardiogram). Airway patency must be ensured, as well as the administration of both oxygen (to maintain sO2 >95%) and saline 0.9% (to maintain adequate blood pressure). In adult patients with hypotension, 1–2 l should be given in the first hour,44 while boluses of 20 ml/kg should be given to children with hypotension every five to 10 min until blood pressure is normalised, with a maximum of 1 l within 30 min.45

If patients suffer from bronchospasms, short-acting beta-adrenergic bronchodilators should be added,46 as well as two to 10 actuations of salbutamol through a mask, which can be repeated every 20 min. Nebulised salbutamol (2.5–5 mg diluted in 3 ml of saline) can also be administered, sometimes in combination with anticholinergics such as ipratropium bromide (0.5 mg).

Antihistamines and steroids are a second line of treatment in anaphylaxis. Their use in isolation is insufficient, so their administration should never delay the use of adrenaline, fluid replacement, or any of the other measures discussed above.47

Finally, once the patient is stabilised, they should be referred to the Emergency Department or the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for further treatment.

Ways to prevent hypersensitivity reactions to radiological contrast mediaPreventive measures should be applied in patients who present any risk factor for developing an HSR. Patients with a history of a previous HSR to CM are most at risk,48 and those who have had a prior severe HSR are reported to have a higher risk of any new reaction being severe again.49

ESUR recommends taking similar precautions in intravascular administration as in intracavitary administration (genitourinary, synovial),12 as HSRs can also develop in intracavitary use, albeit much less frequently.50 Oral or rectal administration of CM does not typically result in ADRs.51

There is also an increased risk of IHSRs associated with the recurrent use of CMs,52 mastocytosis53 and chronic urticarial,49 while renal failure and the use of non-ionic ICMs, especially dimers, may increase the risk of developing a DHSR.54 On the contrary, neither shellfish allergies 55 nor suspected allergies to iodine are risk factors for ICM reactions.56

There are no standardised protocols to prevent recurrent HSRs to CM, and different strategies have been proposed over the years with varying degrees of success, including:

- -

Total avoidance of CM or use of an alternative radiological technique. This recommendation could lead to poor diagnosis for the patient. Moreover, in interventional radiology and haemodynamics, it is difficult to find feasible alternatives.

- -

CM dose reduction and/or infusion speed reduction may control the occurrence of some types of IHSRs that are dependent on non-immunological mechanisms, such as those mediated by MRGPRX2 activation. But it would not prevent allergy-like IHSRs or DHSRs. Moreover, a reduction in ICM infusion rate or flow may lead to a lower quality radiological study.

- -

Premedication using corticosteroids and antihistamines prior to the administration of a CM has been the most widely used method, but its efficacy is now questioned. In Europe, the ESUR12,46 and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI)57 advise against its use whereas guidelines from American scientific societies continue to support it. Some of the limitations identified with regard to premedication include:

▪Its benefit in cases of moderate or severe IHSRs and DHSRs has not been demonstrated58

▪It makes the radiological study more complicated

▪It creates uncertainty for both the patient and the radiologist

▪It causes unnecessary scan delays or cancellations

▪It is hard to implement in an emergency environment

▪Even when used, an HSR can occur after re-administration of ICM (breakthrough reactions) with a high incidence (10–20%).59

If a patient with a history of an IHSR requires the urgent administration of a CM and tolerance has not been confirmed, premedication may be given in the form of dexchlorpheniramine 5 mg combined with methylprednisolone 40 mg or hydrocortisone 200 mg intravenously in a single dose.60 The medication should be administered as soon as the decision has been made to use contrast, and it should not delay the start of the study. If, despite premedication, the patient develops an HSR, treatment should be initiated in line with its severity according to the algorithm in Fig. 2.

- -

Use an alternative CM: switching to a different CM formulation is not a safe approach, due to the high and variable cross-reactivity (CR) between them,60 even if some cases have been reported where the reaction is limited to one CM. The CR is higher for DHSRs than for IHSRs,61 and especially between iodixanol and iohexol, as iodixanol is a dimer of iohexol.

In the search for a safe alternative CM, several classifications have been proposed, based on both chemical structure and clinical outcomes.62,63 Following these criteria, CR would be considered high between iodixanol, iomeprol, iohexol, ioversol and iopramide. Non-ionic ICMs that may have a lower CR are iopamidol and iobitridol, and several clinical studies have confirmed the acceptable tolerability of iobitridol as an alternative.64 However, it has been reported that up to 8% of patients who have a reaction to iobitridol, previously received negative results from skin testing (ST) with this ICM.65

In the case of GBCAs, the possibility of finding an alternative is hindered further by the recommendation to avoid linear GBCAs. CR between macrocyclics is little understood and appears to be largely related to the presence of a similar chelator in their molecules. Therefore, the recent marketing of gadopiclenol, which has a different ligand from the piclene type, could be found to be a useful alternative.

At present, the EAACI and various national allergology societies recommend that all patients who have suffered an HSR to a CM should be referred to an allergy department in order to carry out allergy studies to identify the most appropriate alternatives.54,60Fig. 3 summarises the recommendations for these patients, differentiating between elective and emergency CM-enhanced scanning.

Allergy studies after hypersensitivity reactions to contrast mediaAllergy studies involve ST and provocation testing (PT) with CM. The allergy study is most beneficial when performed within six months after the HSR.27,66,67

ST is a useful, safe tool with a low rate of systemic reaction.67 A range of CMs should be tested in line with the availability at each centre, and should include the CM involved in the previous incident, if known.60 ST is performed with an intradermal or skin prick test at 1:1 concentration, and if the reading is negative after 20 min, an intradermal test is performed at 1:10 concentration with the same ICM and another reading after 20 min.68 In the study of delayed reactions, testing for ST positivity is assessed at 24 h, this being more useful than patch testing.27,69

The specificity of ST is high,66 so any contrast with a positive ST result should not be administered again. However, sensitivity and negative predictive value are low,66,69 especially for delayed reactions. In fact, up to 30‒40% of administrations of a CM for which the patient has previously tested negative, result in an HSR.26,69 Therefore, before recommending its use, it is safer to confirm the tolerance of a contrast with negative ST results through a controlled provocation performed in a hospital allergy department.54,60

While PT is the ultimate test for the diagnosis of HSR to a drug,29,66,70 its use in studying reactions to contrasts is not standardised and it has been underused.66,68,70,71 Several protocols have been published including the administration of incremental doses of contrast with intervals of 30–45 min72,73 and rapid administration protocols with ICM74 and GBCAs21 that resemble the speed of contrast administration in a radiological examination, with good results in terms of safety and efficacy. These studies should be carried out with appropriate measures to reduce the risk of contrast-inducing kidney injury.57,75

Laboratory tests have a poor diagnostic yield. In immediate reactions, determining the levels of serum tryptase can be useful in confirming whether an event is a true HSR, but it does not allow us to differentiate whether the release of mediators has been caused by non-specific or immunological mechanisms. Initiation of treatment for anaphylaxis is not dependent on tryptase test results and should never be delayed; however, these results are useful for the patient’s subsequent allergy study. A minimum of two serial samples should be taken: the first after treatment and stabilisation of the patient and the second, two hours after the onset of the event.76 These results are later compared with the patient's baseline values.

Other in vitro techniques, such as the basophil activation test to study immediate reactions and the lymphocyte transformation test for delayed reactions, are rarely used in routine practice.57,64

ConclusionsWhen an adverse reaction to a CM occurs, we must differentiate between a dose-dependent pharmacological reaction that includes side effects, secondary effects and toxic effects, and hypersensitivity reactions, which are induced by an incongruous reaction of the patient to an appropriate dose of the drug. This article proposes an algorithm that allows radiologists to differentiate between non-specific reactions and true HSRs, and to identify the severity of reactions. In addition, we have proposed a treatment scheme for immediate reactions adjusted to the level of severity, with a particular emphasis on the management of anaphylaxis and the need for early administration of intramuscular adrenaline.

Regarding the management of patients requiring planned or urgent contrast administration who have suffered previous HSRs, current evidence shows that the most effective preventive measure is to use an alternative contrast medium whose tolerance has been confirmed by a previous allergy study. The indiscriminate use of premedication should be avoided.

Author contributions- 1

Research coordinators: FV.

- 2

Study concept: FV.

- 3

Study design: FV.

- 4

Data collection: FV.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: FV.

- 6

Data processing: FV.

- 7

Literature search: FV.

- 8

Drafting of article: FV.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: FV.

- 10

Approval of the final version: FV.

Francisco Vega has collaborated as an external consultant with Laboratorios Rovi.

This research has not received funding support from public sector agencies, the business sector or any non-profit organisations.