This article assesses U.S. security policy on U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry, before and after 9/11. It tracks U.S. security policy’s impact over time by using multiple interrupted time-series (mit) and yearly time-series of border activity measures from 1994 to 2009. The results demonstrate that, other things being equal, post-9/11 U.S. security policy changes had marginal effects; in other words, policy responses make no difference when their performance is compared on, before, and after 9/11; thus, U.S.-Mexico economic integration may be a stronger determinant of security at U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry.

Este artículo evalúa la política de seguridad estadunidense en los puertos de entrada terrestres Estados Unidos-México antes y después del 11 de septiembre. Revisa la política de seguridad de Estados Unidos y su impacto a través del tiempo empleando el análisis de series temporales múltiples interrumpidas y series temporales anuales de la actividad fronteriza para el periodo de 1994 a 2009. Los resultados demuestran que mientras otros asuntos siguen igual, los cambios en la política de seguridad de Estados Unidos después de 11s han tenido efectos marginales. En otras palabras, las medidas adoptadas en materia de políticas públicas no han significado diferencias si se compara su desempeño antes y después de esa fecha; en consecuencia, la integración económica entre los dos países podría ser un determinante de mayor importancia para la seguridad en los puertos de entrada terrestres Estados Unidos-México.

To a large extent, territorial proximity between Mexico and the United States has determined the flow of goods, services, and people through ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico land border (Ramirez, 2009). As a consequence, border security has been a challenge for the U.S. government’s strategic security policy to secure the U.S. homeland after 9/11. Also, the outcomes of the 2008 presidential election made clear that the U.S.-Mexico land border is a political and policy concern in both security and economic terms, because of the increasing flows of people and trade through U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry. So, this article examines U.S. homeland security policy changes along the U.S.-Mexico land border before and after 9/11. Specifically, it investigates how and to what extent 9/11 impacted the dynamics of U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry.

So, section one overviews U.S.-Mexico economic integration in the context of the North American Free Trade Agreement (nafta) and highlights the implications of that process for border security. The section therefore later examines the implementation of U.S. security policy programs (One Face at the Border and us-visit) to enhance security at U.S. ports of entry as mandated by post-9/11 legislation. The section places special emphasis on the organizational changes that principally affected the structure of U.S. security and immigration agencies in charge of protecting the U.S.-Mexican land border such as the Immigration and Naturalization Service (ins). This will help to establish comparative patterns that actually explain security policy performance at U.S. ports of entry located on the U.S.-Mexican land border. Section two carries out a “before and after 9/11 policy assessment,” by making a comparative analysis of the impacts of 9/11 on the U.S. security and border protection policy on the U.S.-Mexico land border. In this section, extended time-series (1994-2009) of the variables and indicators used as proxy measures of border activity are analyzed to isolate out 9/11 as an intervention; the assessment of its effects are the main thrust of section two.

U.S. Security and Border Protection Policy after 9/11: A Policy Assessment of the Mexican FrontAn Overview of the Trade Side: nafta and Economic Integration in North America“Economics does not usefully exist apart from politics” (John Kenneth Galbraith, quoted by Barry Clark, 1998: 3), and “There is no such thing as a purely economic issue” (Milton Friedman, quoted by Barry Clark, 1998:3), are assertions that may describe the U.S. economic policy approach to managing Mexico-to-U.S. bilateral relations. As Clark (1998: 18) put it, “Politics and economics are simply two facets of the process by which society is organized to achieve both individual and community goals. To study this process the … approach provided by political economy is essential.” In this regard, major political-economic events are at the core of political economy (Nurmi, 2006: 6; Watson, 2005). Thus, 1994’s North America Free Trade Agreement (nafta) became the major political and economic issue in the late 1980s and the early 1990s (see McCarthy, 2006: 121-129). As Hettne (2006: 152) pointed out, the U.S. trade regionalist approach before 9/11 was subordinated to political interests and, “this is clear, for instance, in the case of nafta.”

Some (see Weintraub, 1990; Glade and Luiselli, 1989; Benett, 1989; Montes de Oca, 1993; Orme, 1996; Hufbauer, 1993) agree that “it is obvious that, in the aggregate, the U.S. economy is dramatically more affluent and job-rich than the economies of any of its southern neighbours” (Mitchell, 1997: 40). If that is the case, the United States could use several economic policy instruments to affect bilateral relations. According to Martin (1997: 231), three instruments are the most feasible from the U.S. foreign policy perspective: 1) international trade; 2) foreign investment; 3) international aid. And nafta fits well into the first category. Therefore, nafta was the instrument preferred by the U.S. government to deal with its southern neighbor (see also Krugman, 1993; Glade and Luiselli, 1989; Ortmayer, 1997).

At this point, though nafta emerged as a U.S. foreign economic policy instrument to promote economic integration in North America, it is fundamental to be clear that nafta’s main goal was to promote investment and trade among its signees. Originally, Canada and the United States initiated negotiations for a free trade agreement; then in 1990, Mexico joined in to support Mexico’s government commitment to free market policies and economic restructuring. At the same time, nafta formalized strong U.S.-Mexico economic integration and the opening of the Mexican economy to the world market.

At the same time, it is important to emphasize and refer to Mitchell’s argument (1997: 46) that suggests that the hegemonic (economic and political) role played by the United States in Mexico has been influential enough to push forward trade issues like nafta. For instance, in 1993, as part of his campaign to win votes in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives for the free trade agreement with Mexico, President William Clinton said, “If nafta passes, you won’t have what you have now, which is everybody runs up to the maquiladora line [U.S.-Mexico border], gets a job in a factory, and then runs across the line to get a better job. Instead there will be more uniform growth in investment across [Mexico], and people will be able to work at home with their families. And over the period of the next few years, we will dramatically reduce pressures on illegal immigration from Mexico to the United States” (quoted by Cornelius, 2002: 290). At the same time, then-President of Mexico Carlos Salinas de Gortari was promoting a pro-nafta television campaign with the slogan “Exporting goods, not people” (Cornelius, 2002: 290).

Campaigns to pass nafta through Congress were determined; in the United States President Clinton strongly lobbied U.S. congresspersons to pass it; in Mexico President Salinas de Gortari appealed to the Mexican public and Congress. But Mexican political conditions were dramatically different from those in the U.S.; the Mexican political context was principally set up by the Mexican president because of his control over congressional approval (Browne, 1994; Krugman, 1993).

Along these lines, Peter Smith (1997: 265) summarizes all kinds of debate and discussion over nafta expectations and effects in four related hypotheses, as follows: H1: implementation of nafta would lead to a steady reduction in the flow of undocumented workers from Mexico to the United States; H2: implementation of nafta would lead to acceleration in the flow of undocumented workers (and peasants) from Mexico to the United States; H3: implementation of nafta would have no observable effect on the flow of undocumented workers from Mexico to the United States, which would either a) continue at current levels, or b) increase gradually; and, H4: implementation of nafta would have a curvilinear effect on the flow of undocumented workers from Mexico to the United States, increasing the flow in the short to medium term, and thereafter reducing the flow. Without a doubt, intentionally or unintentionally, U.S. policy can directly or indirectly affect security levels in such a way that the flow of investment, trade, and people along the U.S.-Mexico land border do not represent a threat to national security. Neoclassical economic policies developed by international institutions like the International Monetary Fund (imf) and the World Bank (wb) and sponsored by the United States have caused certain disparities in economic growth; visibly, such economic disparities have enlarged the gap between the income of poor and rich countries (Abya, 2004: 256). Thus, many poor people have been pushed to migrate, increasing security concerns in the United States as well as other developed countries; this is particularly true in the aftermath of 9/11.

Therefore, in the context of border security priorities for U.S. government, “As a sovereign nation, it has always been important that we control our borders. But after the attacks of September 11, with the threat posed to our country by international terrorism, it is essential that we do so…. Prior to the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the primary focus of the Border Patrol was on illegal aliens, alien smuggling, and narcotics interdiction…. After 9/11, it was apparent that smugglers’ methods, routes, and modes of transportation are potential vulnerabilities that can be exploited by terrorists and result in terrorist weapons illegally entering the United States. The Border Patrol’s expertise in countering this threat is critical to ensuring the security of the United States” (U.S. Border Patrol National Strategy, 2004). Along these lines, every year more than a million people attempt to get across the U.S.-Mexican land border illegally. For instance, the U.S. Border Patrol apprehended 1 189 000 people in 2005, of whom more than 90 percent were Mexican nationals, the rest of the detainees were from Central and South America (Honduras, El Salvador, Brazil, Guatemala, and others). According to immigration reports released by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (dhs) the number of apprehensions declined to 724 000 in 2008 (Rytina and Simanski, 2009: 1). However, according to the U.S. Office of Immigration Statistics, in 2010, 463 000 were apprehended, representing the lowest level since 1972 and a 70-percent decrease compared to the previous peak at 1 676 000 in 2000. For the dhs, the decline in apprehensions may be the result of poor U.S. economic performance and enhanced border enforcement efforts, among other factors (Rytina and Simanski, 2009: 1-2; Rytina, 2011: 1). This situation has affected the perception about the U.S.-Mexican land border: Carafano and Heyman (2004: 25) point out that on the U.S. “southern border, over 20 000 ‘other than Mexican’ people from ‘countries of interest’ (e.g., Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan) are detained for illegally crossing the border,” making it more vulnerable to terrorist infiltration. The U.S. government’s legitimate concern in dealing with undocumented migration as a national security issue is clear in President Bush’s statement made on October 26, 2006: “Ours is a nation of immigrants. We’re also a nation of law. Unfortunately, the United States has not been in complete control of its borders for decades, and, therefore, illegal immigration has been on the rise. We have a responsibility to address these challenges. We have a responsibility to enforce our laws. We have a responsibility to secure our borders. We take this responsibility seriously” (Bush, 2006).

To reduce the vulnerabilities along U.S. borders, particularly at ports of entry, the Department of Homeland Security created and implemented the “One Face at the Border” and us-visit programs. Both were intended to harmonize the immigration, customs, and agriculture process for U.S. visitors on entering the United States and the visa application process before arriving at a U.S. port of entry. Basically, the programs were created to expedite the identification of safe goods and travelers, so that potential terrorist threats to U.S. homeland security could not enter the United States. The next section presents an overview of the implementation of both programs.

Security at U.S. Ports of Entry after 9/11: The Mexican Front of “One Face at the Border”On September 2, 2003, the then-secretary of the Department of Homeland Security announced the implementation of the Plan “One Face at the Border” (ofab). The ofab program was to unify the inspection processes at U.S. ports of entry. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (cbp) officers were designated to carry it out. An important aspect of implementing the ofab plan was organizational. Before its implementation, the process of inspecting travelers at U.S. ports of entry included three steps: 1) immigration inspection; 2) customs inspection; and 3) agricultural inspection (when the travelers transported food or plants). However, ofab’s main task was to merge those three steps into a single process by cross-training cbp officers to carry out the three processes at any U.S. port of entry (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2009a). By unifying the inspection process, ofab created the position of cbp officer as part of the dhs. Since then, cbp officers have been trained to perform immigration (people), customs (goods), and agriculture (farm products) activities at ports of entry. In this way, a cbp officer became “the principal front line officer carrying out the priority mission [prevent terrorists from entering the U.S.] and the traditional customs, immigration, and some agriculture inspection functions” (Meyers, 2005a: 8).

According to dhs officials, ofab was to increase efficiency for managing U.S. ports of entry by creating the cbp position (White House, 2003), so that travelers meet a single inspection officer with the necessary training to determine what/who goes through secondary inspections. In this way, increasing efficiencies and unity around a single mission created significant levels of homeland security. Also, by getting the primary inspector trained to refer travelers whose information or actions raise questions to secondary inspectors, so additional questioning was completed at secondary inspection facilities to, a) prevent terrorists and terrorist weapons from entering the country; b) deny entry to people seeking to enter illegally; and, c) protect U.S. agricultural and economic interests from pests and diseases. Finally, counter-terrorism response (ctr) inspectors are deployed as secondary inspectors to conduct follow-up examinations of questionable passengers who could be tied to terrorism. ctr inspectors are responsible for, a) coordinating with the local Passenger Analysis Unit and National Targeting Center the research process for fully screening travelers; and, b) detaining travelers whom they find to be in violation of the law.

In this framework, for dhs officials, if one person performs three activities at the same time, the number of cbp and other dhs employees in secondary inspection facilities may be increased. As a result, additional personnel are dedicated to track passengers with suspicious behavior in secondary inspection. For the dhs “unifying three dedicated but separate workforces into one U.S. Customs and Border Protection Officer, cross-trained to address all three inspection needs, is another significant step toward Homeland Security’s effort to make the most effective use of the Department’s assets and thus better secure our homeland” (White House, 2003). The main effects, if any, of ofab “may be more noticeable to travelers through the visual unification that has occurred. cbp Officers (inspectors and supervisors alike) have been outfitted with dark blue uniforms, new patches, and new caps, all with the cbp logo.” Prior to the implementation of ofab, the officers of the agencies dressed differently (Meyers, 2005a: 11). Border Patrol agent Wendy Lee commented that ports of entry have undergone minor modifications, though more “Smart Border” and security infrastructure has been installed, and confirmed that cbp officers are trained to develop three tasks: immigration, customs, and agriculture inspections. Similarly, Meyers (2005a: 11) point outs that a visible advantage of ofab is that cbp officers are “a single point of contact with outsiders, a reduction in duplicative efforts, and the ability to allocate more resources to facilitating trade and travel and anti-terrorism efforts, including having ports operate under the same alert level and the same set of guidelines.” cbp officers’ anti-terrorism effort is supported by the National Targeting Centers (NTC), which provide bio-terrorism prevention and radiological assessment at ports of entry. Though important for cbp officers, this high-tech technology tool is not visible to U.S. visitors while they go through the inspection process to enter the country.

The US-Visit ProgramThe United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology System (us-visit program) is another U.S. government effort to enhance homeland security while potential terrorists intend to do harm on U.S. soil. In accordance with the provisions of the U.S. Patriot Act of 20011 and the post-9/11 legislation for homeland security, the secretary of homeland security created the us-visit program within the Border and Transportation Security (bts) Directorate, and implemented it on December 31, 2004. us-visit was especially designed to “identify visitors who may pose a threat to the security of the United States, who may have violated the terms of their admission to the United States, or who may be wanted for the commission of a crime in the United States or elsewhere, while simultaneously facilitating legitimate travel and trade” (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2005: 6). It is important to note that us-visit is a biometric system that establishes the capacity to electronically record the entry and exit of the visitors passing through checkpoints at U.S. ports of entry. In this way, us-visit harmonizes entry-exit records. Thus, dhs officers may determine whether visitors overstay the period and conditions of their admission to the country by determining their identities (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2005: 6).

Initially, the program was implemented only at some U.S. land ports of entry: Douglas, Arizona; Laredo, Texas; and Port Huron–Blue Water Bridge, Michigan in November 2004. Later, it was completely implemented at the remaining U.S. air, land, and sea ports of entry. Basically, the program consisted of deploying an electronic system for cbp officers to record international travelers’ personal information (except that of U.S. citizens). For cbp officers, the registration process consists of passing the readable passports and visas through reader machines; after that, all foreign visitors (including nationals of countries in the Visa Waiver Program) travelling to the United States have their two index fingers scanned and a digital photo taken to match and authenticate their travel documents.2 The system is connected to anti-terrorism centers and terrorist watch-lists of the cia, fbi, dhs, and the U.S. Border Patrol to match travelers with wanted criminals and terrorists on the lists.3 Despite the sensitive information that the U.S. government intended to collect by implementing the us-visit program, some exemptions have been applied to register Mexican and Canadian nationals, who account for more than 80 percent of those crossing through U.S. land ports of entry on the U.S.-Canada and U.S.-Mexico land borders. In the case of Mexicans, the U.S. government issued a special type of visa (Biometric B1/B2/bcc), also known as the “Laser Visa.” This has been issued exclusively to Mexican nationals, and it allows them to enter the United States either on a business (B1) or tourist (B2) visitor, and for multiple entries through the U.S.-Mexican land border (Border Crossing Card, or bcc).

Mexican nationals in possession of a bcc visa are exempt from enrolling in the us-visit program. More than 45 percent of the crossings through the U.S.-Mexican land border are bcc crossings (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2005: 4). Canadians who do not have a U.S. visa can be admitted to the United States with limited information, such as a passport or any other government-issued document that may be used to verify travelers’ identity. Mexicans using a “Laser Visa” issued prior to October 1, 2008 or a new laminated card (with enhanced graphics and technology) are required to register in the us-visit program only once by filling out a I-94 Form. They are allowed to use that I-94 Form for up to six months and for multiple entries; in this way Mexicans do not have to enroll in the us-visit each time they cross the border, but simply renew their I-94 Form when it expires. It is important to mention here that Mexicans with “Laser Visas” who cross the U.S.-Mexico land border are required to register in the us-visit program through the six-month I-94 Form only when they want to go 25 miles beyond the U.S.-Mexico border; otherwise they can use their “Laser Visas” to cross the border and move within a 25-mile radius from any point along the land border.4 For example, Mexicans crossing by land from Tijuana, Mexico to San Diego, California through San Ysidro can use their “Laser Visas” to go up to downtown San Diego; if they attempt to go without an I-94 Form farther than that 25-mile limit, they are violating the conditions of their admission to the United States. So, the cbp Border Patrol in San Diego has a full-time traffic checkpoint on the northbound lanes of Interstate 5 in San Clemente, California, just outside of San Diego County and halfway to Los Angeles. The strategic location of the San Clemente checkpoint enhances the effect of Border Patrol activities against smuggling of illegal aliens and narcotics through the San Diego, California-Tijuana, Mexico land border.

Preliminary results of the security strategy show that from December 2004 to January 2007, the us-visit program processed more than 76 million visitors between the ages of 14 and 79. The U.S. government apportioned more than US$390 million for the program for fiscal year 2009 as a way to increase its biometric identification capabilities, which have resulted in more than 7 000 matches or “hits” on law enforcement databases. As a result, about 1 800 immigration violators and people with criminal records have been intercepted. The Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ice) office of the dhs has made more than 290 arrests based on overstay information collected from the us-visit program (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2009b; Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, 2013).

So far, apart from the us-visit program’s difficulty in enrolling travelers such as Mexican and Canadian nationals in multiple entries, it lacks an efficient automated component for tracking visitors’ exits; therefore, travelers are not required to enroll in any us-visit exit component. Without the exit component, the program is unable to match entry and exit records and cannot identify non-immigrants or visitors who violate the conditions of their stay in the United States. This feature and the impossibility of registering multiple entries at U.S. ports of entry have weakened the program and made it more unreliable for tracking possible threats along the U.S.-Mexican land border.

At this stage, it is still difficult to establish to what extent the implementation of both programs has increased U.S. homeland security by regulating the flows of people through ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexican land border to make it safer. This is particularly true if we take into consideration that ofab has marginally modified the security infrastructure at U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry, and its only organizational strength is the creation of the position of cbp officer to integrate three inspection processes into one. Nevertheless, the technology improvements are remarkable.

In addition, the us-visit Program has failed to register Mexican visa holders’ multiple entries, and it is incomplete without an efficient exit component to collect reliable records of departures, so that border protection policymaking can be more efficient in reducing negative impacts on migrants’ rights along the land border. It is also debatable whether the 9/11 events alone had a profound and lasting effect on the dynamics of the U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry. Thus, this article suggests that the level of integration between the United States and Mexico (economic, social, political, cultural integration) may be a stronger determinant of what is happening at U.S. ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexican land border, and that dhs security programs have had only marginal effects, given the border’s long-standing dynamics. Therefore, the following subsection offers a more detailed analysis of this argument.

Relating 9/11 and Border Activity at U.S.-Mexico Land Ports of Entry: A Statistical AnalysisIn extending and expanding the narrow academic work on the effects of 9/11 on the dynamics of U.S. ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexican land border, this article develops a statistical analysis to contribute to estimating policy impacts. It utilizes monthly time series (1994-2009) of five measures of border activity at U.S. land ports of entry in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. These five measures are the number of bus crossings from Mexico to the U.S.; bus passengers, or the number of people who crossed the border by bus; the number of pedestrian crossings; personal vehicles, or the number of private cars that crossed the border every month; and passengers in personal vehicles, or the number of people crossing the border in private cars. Also, we use a dummy variable to measure the intervention effect of 9/11 as temporary or permanent. In this case, a temporary effect of the 9/11 dummy means that the effect, if any, lasted for only one period of the monthly time series. In other words, a temporary effect of 9/11 in this analysis lasts only one month and disappears in the t+2 period or in the next month (in general, t = t+1 ≠ t+2…t+n). A permanent effect of 9/11 persists until the end of the time series (t = t+1 = t+2…t+n), in this case until the last month of 2004. The 9/11 dummy is dichotomous with zero before 9/11 occurred and one on and after the months after 9/11; here it is important to note that this techniques makes it possible to isolate solely the effect of 9/11.

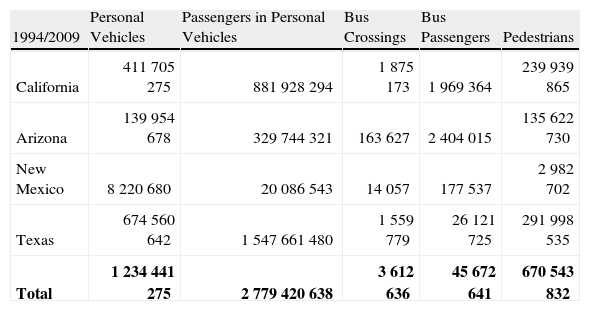

For example, from 1994 to 2009 more than one billion personal vehicles crossed the border from Mexico to the U.S., and almost three billion passengers in personal vehicles; about 3.6 million buses crossed the border, and more than 45 million people crossed as bus passengers. Finally, more than 670 million pedestrians crossed (see Table 1, which shows the aggregated values of the monthly data set from 1994 to 2009 for each measure of border activity and U.S. border states).

Measures of border activity at U.S. ports of entry on the U.S.-Mexico land border, 1994-2008

| 1994/2009 | Personal Vehicles | Passengers in Personal Vehicles | Bus Crossings | Bus Passengers | Pedestrians |

| California | 411 705 275 | 881 928 294 | 1 875 173 | 1 969 364 | 239 939 865 |

| Arizona | 139 954 678 | 329 744 321 | 163 627 | 2 404 015 | 135 622 730 |

| New Mexico | 8 220 680 | 20 086 543 | 14 057 | 177 537 | 2 982 702 |

| Texas | 674 560 642 | 1 547 661 480 | 1 559 779 | 26 121 725 | 291 998 535 |

| Total | 1 234 441 275 | 2 779 420 638 | 3 612 636 | 45 672 641 | 670 543 832 |

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation, n.d.

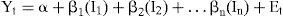

Disaggregated data from Table 1 is used for the analysis of interrupted time series (its). First, the formal relationship between the variables in this its approach is

Yt = the dependent variable at time t (bus crossing, bus passengers, pedestrian crossing, number of vehicles, passengers per vehicle)

β1….n = parameter estimate

I1…n = independent intervention variable coded as a dichotomous dummy (9/11)

E = error term.

Some studies in the social sciences have used its linear regression techniques to analyze the long-term effects of single public policy interventions, economic phenomena, or other social events. For instance, Lewis-Beck (1979: 1131-32) analyses the economic effects of revolutions and applies the its approach to investigate the effects of the Cuban Revolution on Cuban sugar production; Foweraker and Landman (1997: 195-224) are known for using a version of multiple time series (mits a modified version of its) to correlate measures and indicators of citizenship rights and social movements for multiple years; Glass, Tiao and Maguire (1971) employed its regression analysis for estimating the effects of the 1900 revision of German divorce laws on divorce rates and petition for divorce; Box and Tiao (1975) carried out an intervention analysis with applications to economic and environmental problems. In their research, they raised questions like, “Given a known intervention, is there evidence that change in the series of the kind expected actually occurred, and, if so, what can be said of the nature and magnitude of the change?” (Box and Tiao, 1975). Box and Tiao (1975: 70) examined the case of two policy interventions to reduce the pollution level in downtown Los Angeles in the 1960s.5

Second, autoregressive techniques facilitate relating border activity (dependent variable) and 9/11 (independent dummy variable).6 Thus, by regressing the dependent variable on the independent variable, the effects, if any, are distinguishable; in other words the 9/11 effect is isolated out. The regression results are to identify the magnitude of the effect the intervention has on the dependent variable, the type of effect (negative or positive), and the significance of the effect; the analysis presented here is only concerned with investigating the type and significance of the effect of 9/11 on border activity, and not with the magnitude (Foweraker and Landman, 1997: 197; Morh, 1995).

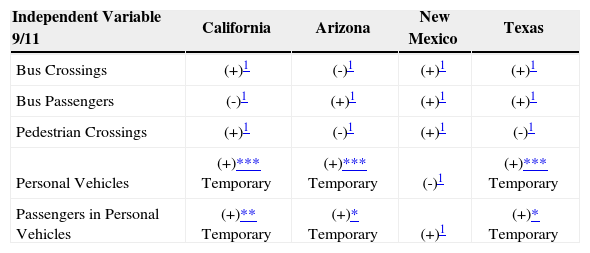

Returning to the case of this research and its purposes, Table 2 shows the signs of the linear regression parameter estimates and their significance that resulted from regressing the five measures of border activity at ports of entry for each of the U.S. border states (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) on the 9/11 dummy variable. It is important to note that 40 its regressions were run in total for all possible effects; this is five temporary and five permanent effects of 9/11 on the measures of border activity for four border states ([5temporary + 5permanent] * 4States = 40). However, Table 2 only includes those results that are theoretically and statistically consistent. From the table, it is clear that only six results out of twenty show temporary, positive, and significant effects for 9/11. The vertical left line of Table 2 shows the five measures of border activity; the 9/11 variable and the U.S. border states (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) are along the top row of the table. The signs in parentheses reveal the type of effect that 9/11 had on each measure of border activity for each U.S. border state. At the same time, Table 2 shows the temporary or permanent effect, and the level of significance that the independent variable (9/11) had on the dependent variable (measures of border activity). In the case of California, 9/11 had a positive, but temporary effect on the measures of personal vehicles and passengers in personal vehicles. The rest of the cases are not significant. Similarly, Arizona has two positive and temporary effects from 9/11, one is personal vehicles and the other is passengers in personal vehicles. Finally, Texas, similarly to California and Arizona, has two positive effects from 9/11: on personal vehicles and passengers in personal vehicles (Table 2 below summarizes this information).

Parameter estimates of the impact of 9/11 on border activity at ports of entry on the U.S.-mexican land border

| Independent Variable 9/11 | California | Arizona | New Mexico | Texas |

| Bus Crossings | (+)1 | (-)1 | (+)1 | (+)1 |

| Bus Passengers | (-)1 | (+)1 | (+)1 | (+)1 |

| Pedestrian Crossings | (+)1 | (-)1 | (+)1 | (-)1 |

| Personal Vehicles | (+)*** Temporary | (+)*** Temporary | (-)1 | (+)*** Temporary |

| Passengers in Personal Vehicles | (+)** Temporary | (+)* Temporary | (+)1 | (+)* Temporary |

Notes:

So far, the its regression analysis has served to establish the type and significance of the 9/11 effects. In the six significant cases with a positive effect, this means that 9/11 somehow temporarily increased (one monthly period) the flows of people crossing by car, and the number of personal vehicles entering through California, Arizona, and Texas; whereas the cases in which there is no statistical significance, the 9/11 interruption had no effect at all. This may suggest that perhaps other variables may be more strongly related to border activity, but they are not a concern of this analysis. The findings are inconclusive, and some caution is necessary in interpreting them, as they may appear counter-intuitive. However, they may be explained in part by the increased uncertainty that emerged along the U.S.-Mexican land border when the U.S. government wanted to seal off the border for an undetermined period, or until the U.S. security agencies gained complete control of it in the aftermath of 9/11. At the same time, even when uncertainty was high and increasing daily after 9/11, the following factors must be taken into consideration and any conclusion must be viewed with caution:

- •

Data availability, its nature, and the its approach: the data to build the measures of border activity is monthly because activity between ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico land border is not the main thrust of the research. The events of 9/11 occurred almost halfway through September. Whatever type of disruption was caused by 9/11, it took place in the three or four weeks after September 11, as suggested by qualitative information gathered from talks with locals on the California-Mexico land border and Border Patrol agents. On the one hand, this means that September and October 2001 partially captured shockwave from 9/11, which was probably divided over the two monthly periods of the data. On the other hand, in this analysis, the its approach assumes that a temporary effect lasts one period after the intervention or shock. In other words, September 2001 is the period of intervention; this lasted until October 2001, the month after the intervention, and disappeared during the next monthly period.

- •

U.S.-Mexico Interdependence: as argued earlier, the temporary effect of 9/11 may be explained by the strong U.S.-Mexico economic, social, and political interdependence. These factors may be seen as stronger determinants of the dynamics of the U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry; the big flows of people and trade forced U.S. security officials to return border activity to normal as soon as possible after 9/11 as lines of people and cars stretched for miles, lasted for hours, disrupting the regular flows of students and workers, and cutting the supply lines of cross-border manufacturing networks (Weintraub, 1990; Krugman, 1993; Martin, 1993; Russell, 1994; Ortmayer, 1997; Bair, 1990; Cornelius, 2002; Pastor, 2002; Hanson, 2004; Meyers, 2003; Papademetriou, Cooper, and Yale-Loehr, 2005).

Therefore, only a temporary effect from 9/11 is expected; this makes the results of Table 2 more reasonable since a permanent effect would make no sense, given the integration between Mexico and the U.S. border states. In other words, in the circumstances of the present analysis permanent effects might be a-theoretical. For instance, the states of California, Arizona, and Texas have solid, long-standing two-way connections of trade, people, and culture with Mexico, factors that make permanent disruption from 9/11 implausible. Furthermore, this integration process has strengthened since nafta took effect in January 1994.

To a certain extent, the results reported in Table 2 formalize this situation. As pointed out at the beginning of section one, a free-trade-agreement approach emerged as a U.S. foreign economic policy instrument to promote economic integration in North America. It is fundamental to make clear that the issue of Mexican undocumented “economic” migration was not the main reason for creating nafta. Indeed, the main goal of nafta was to promote investment and trade among its members. Originally, Canada and the United States initiated negotiations for a free trade agreement; then, in 1990, Mexico joined the negotiations to support the Mexican government’s commitment to free market policies and economic restructuring. At the same time, nafta formalized the strong U.S.-Mexican economic integration and the opening of the Mexican economy to the world market. However, Mexican trade representatives put the issue of undocumented “economic” migration from Mexico on the table for discussion.

Expectations of including undocumented migration as part of nafta disappeared when U.S. trade representatives tried to include Mexico’s oil industry along the lines established for discussing undocumented migration. In the end, both issues were left aside in the negotiations because they were considered two sensitive issue areas by U.S. and Mexican public opinion. So, given the policy assessment approach adopted in the research presented here, I argue that the linkage between nafta and undocumented economic migration was based on political concerns. In other words, here, my contention is that, to make the agreement politically feasible, nafta promoters in Mexico and the U.S. utilized the issue of undocumented “economic” migration to “sell” the agreement and gain political approval on the basis that nafta could reduce undocumented migration.

Alternatively, certain qualitative data may provide some insight into the quantitative analysis of the findings already reported already in Table 2. For example, during field research in the San Diego area, people commented that for several weeks after 9/11, wait times for crossing the border rose to more than six hours. Raul Gonzales Rodriguez mentioned that on 9/11 he was queuing to cross the border from Tijuana to San Diego, when suddenly INS personnel started closing the entries.7 The entrance remained closed for more than four hours, after which INS personnel opened the lanes to let cars and people cross. However, each and every car and person was carefully searched because there was information suggesting that terrorists could use the U.S.-Mexico border to get away to Mexico (Meyers, 2003).

Professor Rodriguez and other interviewees along the border commented that many Tijuana residents work in San Diego and other towns on the U.S. side, so they were afraid of losing their jobs if the border was sealed off permanently. For that reason, many people began to move to California or stayed there longer until border-crossings times were back to normal. People who decided to move to California returned to pick up their families and belongings in Tijuana. This ensured that the number of people crossing the border increased as did the number of vehicles. The INS search process and the number of people and cars crossing the border upped the crossing “wait times.” Weeks later, things seemed to return to normal, so flows of people and cars began to stabilize, and the border crossing wait times returned to normal, too.

Final RemarksTo a large extent, this study constitutes an attempt to gain further understanding of the potential of U.S. security policy changes for protecting the U.S.-Mexico land border against international terrorism and undocumented migration in the aftermath of 9/11. The analysis carried out in this article intends to answer the following general question: Do post-9/11 U.S. security and border protection policies make any difference in the protection of the U.S.-Mexican land border against international terrorism? In particular, it investigates how and to what extent 9/11 impacted the dynamics of U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry. With that aim in mind, the article examines the implementation of the “One Face at the Border” and us-visit programs that were implemented to secure U.S. sea, air, and land ports of entry against undocumented immigration and terrorist infiltration. This policy analysis facilitated the assessment of the impact of these programs, and 9/11 itself on activity in U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry. It was carried out by using its regression analysis as a technique to relate five measures of border activity (bus crossings, crossings of passengers on buses, pedestrian crossings, personal vehicle crossings, and crossings of passengers in personal vehicles) and a 9/11 dummy variable to estimate the effects as temporary or permanent. Within this framework, the balance of evidence presented throughout provides elements to assess U.S. security policy performance on the Mexican front. First, as previously noted, the ofab and us-visit programs were implemented as part of post-9/11 security policy changes; however, those changes only slightly modified the operation of U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry. This is because thep osition of the dhs official was created to merge three inspection activities into one. In these circumstances, this type of policy change is mostly symbolic and only guarantees a more secure port of entry rather than a safer one. Therefore, a process of restructuring security programs offers limited results and unsuccessful policies. Second, the analysis of the Mexican front also demonstrated that, other things being equal, U.S.-Mexico economic and social integration largely determine the dynamics of U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry. The its analysis showed, for example, that if 9/11 had any impact on the land ports, it was temporary, but unimportant, in Texas, California, and Arizona, and had no impact at all in New Mexico. In this way, the findings uncovered by the analysis, though tentative, constitute a dimension that deserves deeper and more considered work. After 9/11, academic research on U.S.-Mexico land border activity will always be needed, in particular, research focused on the interactions of economic integration and security priorities in North America.

The U.S. Patriot Act of 2001 mandated the implementation of an electronic entry-exit program to record the identities of visitors to the United States. However, this is related to a minor provision of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, which required the U.S. government to create and implement a similar program to prevent U.S. visa holders from overstaying their visas and violating the non-immigrant conditions of visitor and tourist visas.

For further information about the us-visit enrollment and Visa Waiver Program, go to http://www.dhs.gov/xtrvlsec/programs/editorial_0527.shtm at the dhs website.

us-visit includes the following systems, among others: 1) the Arrival Departure Information System (adis), which stores traveler arrival and departure information; 2) the Advance Passenger Information System (apis), which contains arrival and departure manifest information; 3) the Computer Linked Application Information Management System 3 (claims 3), which encompasses information on foreign nationals who request benefits; 4) the Interagency Border Inspection System (ibis), which maintains “lookout” data and interfaces with the Interpol and National Crime Information Center (ncic) databases; 5) the Automated Biometric Identification System (ident), which stores biometric data of foreign visitors; 6) the Student Exchange Visitor Information System (sevis), a system containing information on foreign students in the United States; and, 7) the Consular Consolidated Database (ccd), which includes information about whether an individual holds a valid visa or has previously applied for a visa.

For more details about the applicability of us-visit to Mexicans, see http://www.homelandsecurity.state.pa.us/homelandsecurity/cwp/view.asp?A=519&Q=172105, and U.S. Government Accountability Office Report, at http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/library/P2603.pdf, accessed September 2013.

Also see Morh (1995) for further details of the its technique and intervention analysis.

Autoregressive techniques are useful for solving the problem of autocorrelation common in interrupted time series; therefore, in this section, autoregressive linear models are run to estimate the parameter estimates shown in Table 2.

Raul Gonzales Rodriguez is a university professor in Chicano studies and U.S. American history at cetys Universidad in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. He also teaches Mexican-American culture at San Diego State University (sdsu). He crosses the border four or five times a week either to teach at SDSU or shop in San Diego and San Ysidro, California. Professor Gonzales was the contact in the California-Mexico border area for collecting qualitative data and carrying out interviews with local people and potential Mexican undocumented migrants.