The medical residency (MIR) exam has been held annually since 1978 by the Ministry of Health and is held on the same day and time throughout Spain. It was created with the aim of providing access to specialist training.1 For a number of years, it has shared this responsibility with Medical Specialisation Schools, the Faculties of Medicine, the exams held in accredited hospitals and the validation of qualifications obtained abroad.2 It was not until 1984 that the medical residency exam (MIR) became the main way of entering the system for obtaining the title of specialist.3 This specialisation can now also be achieved through the validation of foreign qualifications.

Although there have been slight variations in the number of questions and time allowed in recent years, it is currently a 200-question multiple-choice test (plus 10 additional reserve questions in case of cancellations), to be completed in a maximum of 4.5 h.4,5

The mark obtained in this exam (90% of the final mark), together with the evaluation of the academic record (10% of the final mark), will allow the ranking of all candidates in descending order of score.6,7

The candidate with the highest score starts the selection process, which in recent years has taken place between the end of April and the beginning of May, and joins the chosen destination a few weeks later.8,9 The number of vacancies offered in the medical residency (MIR) exam has been increasing, especially in recent years, from 7615 vacancies in 2020 to 8772 in 2024. The total number of medical specialties offered is 46.

If we analyse the number of vacancies in the last call for applications (2024), the specialty of general practitioner (GP) is the one with the most vacancies (2492) (28.4% of the total number of vacancies offered). It is followed by the specialties of paediatrics with 508 vacancies (5.8% of the total) and internal medicine with 425 vacancies (4.8% of the total number of vacancies).

Internal medicine is one of the medical specialties whose offer has been progressively increasing in recent years, from 360 vacancies in 2020 to the current 425, representing an 18% increase in vacancies in 5 years.

If we analyse the average offer of the rest of the 45 specialties, this was 161 vacancies in the 2020 call, 168 vacancies in 2021, 173 vacancies in 2022, 180 vacancies in 2023 and 185 vacancies in 2024. This means that the specialty of internal medicine has doubled the average offer of the rest of the specialties in each of the last 5 medical residency (MIR) calls.

This situation regarding the specialty of internal medicine is particularly relevant to understand why vacancies in this specialty are filled later than in other specialties with fewer vacancies on offer. The greater the number of vacancies in a specialty, the more candidates will have to apply to fill all the vacancies and, consequently, it is chosen earlier during the selection process. This situation does not necessarily mean that the specialty of internal medicine is less attractive than other specialties filled earlier.

The aim of this study is to estimate, based on the data on the number of medical residency (MIR) candidates filling a vacancy in the last 5 calls for applications (2020–2024), the degree of attractiveness to the specialty of internal medicine.

In order to measure the level of interest of medical residency (MIR) candidates for a specialty, an indicator called the Competitive Preference Index (CPI) has been developed.10 The five most populated cities in Spain, Barcelona, Madrid, Seville, Valencia and Zaragoza, were chosen. In these cities, the candidate who chose the last of the internal medicine vacancies advertised varied from the candidate with order number 2098 in Valencia in 2021 to the candidate with order number 6823 in Zaragoza in 2023, obtaining an average order number of 5089 for the candidate who chose the last of the internal medicine vacancies during the period analysed.

MethodologyThe database on the selection number related to the vacancies allocated to each specialty was obtained from the website of the Ministry of Health from 2020 to 2024.11

In order to make the analysis more robust and to obtain a more homogeneous sample, the 5 Spanish cities with the largest populations (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Seville and Zaragoza) were chosen for the analysis, as these are the cities where most of the 46 specialties are offered and where there is an adequate and sufficient number of vacancies for each specialty to be comparable. The analysis of these 5 cities has been carried out on the basis of the locality referred to in the aforementioned database.

Competitive preference indexThe CPI10 was calculated to measure the degree of attractiveness of internal medicine compared to other specialties.

The CPI was calculated as follows: For each specialty other than internal medicine, the order number of the last person who filled a vacancy in the study city was obtained and compared with that of the last person who filled a vacancy in internal medicine in the same city. Once the lower of these 2 numbers had been obtained, all the people who chose any of the 2 specialties with a number equal to or lower than these 2 numbers were selected, i.e. all those people who had the real opportunity to choose between these 2 specialties in the city analysed. Finally, from this set of people, we obtained the CPI percentage who chose internal medicine as a measure of the competitive preference between the two specialties.

The following formula summarises the CPI calculation:

Where nB_vacancies (A) is the number of vacancies in specialty A chosen before the available vacancies in specialty B were filled, and nA_vacancies (B) is the number of vacancies in specialty B that were chosen before the available vacancies in specialty A were filled.In our study, A is the specialty of internal medicine and B is all other specialties. This index is based on the comparison of internal medicine (A) with each specialty (B), taking into account the equal opportunity of choosing internal medicine or another specialty. The CPI is constructed on the premise of controlling for the effect of inequality of offer between internal medicine and other specialties.

The CPI has been calculated using data for the correlative calls from 2020 to 2024.

In Example 1 of Appendix B Supplementary material, specialties were analysed individually, and grouped by medical, surgical, laboratory/central services specialties.

CPI values equal to or greater than 50% (highlighted in bold) indicate a positive competitive preference for internal medicine over the other specialty. CPI values below 50% (not highlighted) indicate a negative competitive preference.

Statistical analysisThe study contains 2 phases. In the first phase, the CPI was calculated individually for each of the study cities (Barcelona, Madrid, Seville, Valencia and Zaragoza), and for each year in the period between 2020 and 2024. The second phase includes an analysis of the evolution of this continuous and aggregate variable for each type of specialty, as well as the calculation of the overall CPI averages by city and the calculation of the percentage of specialties that have a CPI greater than or equal to 50% (positive CPI).

All analyses have been performed with R version 4.0.0.

ResultsThe total number of medical residency (MIR) vacancies offered is 7512 in 2020, 7988 in 2021, 8188 in 2022, 8550 in 2023 and 8772 in 2024. Internal medicine is the third specialty offering the most vacancies, with a total of 360 vacancies in 2020, 389 vacancies in 2021, 401 vacancies in 2022, 413 vacancies in 2023 and 425 vacancies in 2024.

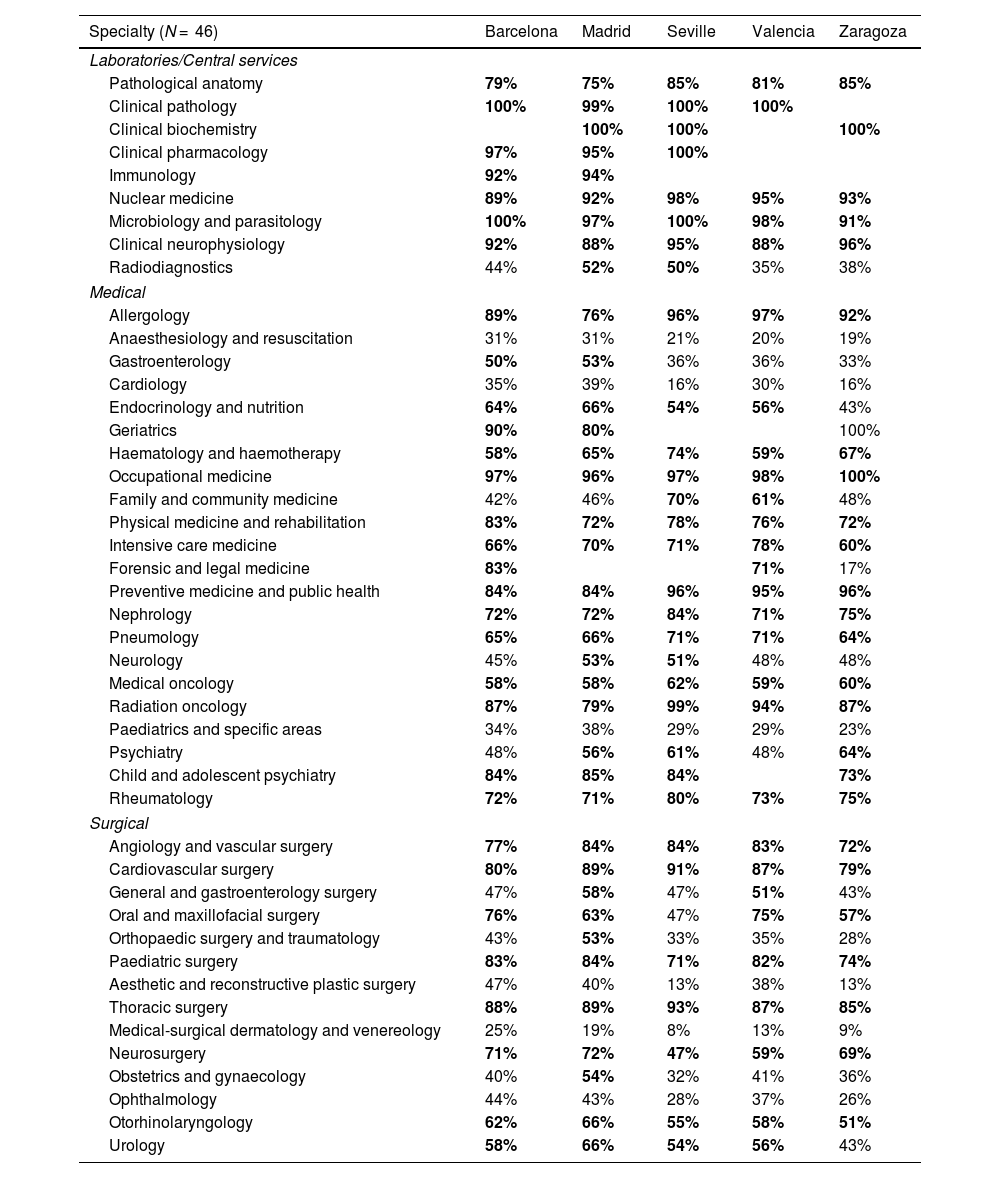

Table 1 shows the average CPI results (years 2020–2024) for internal medicine compared to the other specialties.

Average competitive preference index (years 2020 to 2024) for internal medicine compared to other specialties.

| Specialty (N = 46) | Barcelona | Madrid | Seville | Valencia | Zaragoza |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratories/Central services | |||||

| Pathological anatomy | 79% | 75% | 85% | 81% | 85% |

| Clinical pathology | 100% | 99% | 100% | 100% | |

| Clinical biochemistry | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Clinical pharmacology | 97% | 95% | 100% | ||

| Immunology | 92% | 94% | |||

| Nuclear medicine | 89% | 92% | 98% | 95% | 93% |

| Microbiology and parasitology | 100% | 97% | 100% | 98% | 91% |

| Clinical neurophysiology | 92% | 88% | 95% | 88% | 96% |

| Radiodiagnostics | 44% | 52% | 50% | 35% | 38% |

| Medical | |||||

| Allergology | 89% | 76% | 96% | 97% | 92% |

| Anaesthesiology and resuscitation | 31% | 31% | 21% | 20% | 19% |

| Gastroenterology | 50% | 53% | 36% | 36% | 33% |

| Cardiology | 35% | 39% | 16% | 30% | 16% |

| Endocrinology and nutrition | 64% | 66% | 54% | 56% | 43% |

| Geriatrics | 90% | 80% | 100% | ||

| Haematology and haemotherapy | 58% | 65% | 74% | 59% | 67% |

| Occupational medicine | 97% | 96% | 97% | 98% | 100% |

| Family and community medicine | 42% | 46% | 70% | 61% | 48% |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 83% | 72% | 78% | 76% | 72% |

| Intensive care medicine | 66% | 70% | 71% | 78% | 60% |

| Forensic and legal medicine | 83% | 71% | 17% | ||

| Preventive medicine and public health | 84% | 84% | 96% | 95% | 96% |

| Nephrology | 72% | 72% | 84% | 71% | 75% |

| Pneumology | 65% | 66% | 71% | 71% | 64% |

| Neurology | 45% | 53% | 51% | 48% | 48% |

| Medical oncology | 58% | 58% | 62% | 59% | 60% |

| Radiation oncology | 87% | 79% | 99% | 94% | 87% |

| Paediatrics and specific areas | 34% | 38% | 29% | 29% | 23% |

| Psychiatry | 48% | 56% | 61% | 48% | 64% |

| Child and adolescent psychiatry | 84% | 85% | 84% | 73% | |

| Rheumatology | 72% | 71% | 80% | 73% | 75% |

| Surgical | |||||

| Angiology and vascular surgery | 77% | 84% | 84% | 83% | 72% |

| Cardiovascular surgery | 80% | 89% | 91% | 87% | 79% |

| General and gastroenterology surgery | 47% | 58% | 47% | 51% | 43% |

| Oral and maxillofacial surgery | 76% | 63% | 47% | 75% | 57% |

| Orthopaedic surgery and traumatology | 43% | 53% | 33% | 35% | 28% |

| Paediatric surgery | 83% | 84% | 71% | 82% | 74% |

| Aesthetic and reconstructive plastic surgery | 47% | 40% | 13% | 38% | 13% |

| Thoracic surgery | 88% | 89% | 93% | 87% | 85% |

| Medical-surgical dermatology and venereology | 25% | 19% | 8% | 13% | 9% |

| Neurosurgery | 71% | 72% | 47% | 59% | 69% |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 40% | 54% | 32% | 41% | 36% |

| Ophthalmology | 44% | 43% | 28% | 37% | 26% |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 62% | 66% | 55% | 58% | 51% |

| Urology | 58% | 66% | 54% | 56% | 43% |

The blanks are due to the fact that the specialty is not offered in these cities.

In bold, CPI values equal or above 50%.

In relation to laboratory/central services specialties, the average CPI for internal medicine was positive for all specialties (anatomical pathology, clinical pathology, biochemistry, pharmacology, immunology, nuclear medicine, microbiology and neurophysiology) in all the cities analysed with the exception of radiodiagnosis in Barcelona (44%), Valencia (35%) and Zaragoza (38%).

In relation to medical specialties, the average CPI for internal medicine is positive in all the cities analysed for 13 specialties (allergology, geriatrics, haematology, occupational medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, intensive care medicine, preventive medicine, nephrology, pneumology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, child psychiatry and rheumatology). Anaesthesiology, cardiology and paediatrics are more attractive than internal medicine in all the cities analysed. Family and community medicine, neurology and gastroenterology are more attractive in 3 of the 5 cities analysed.

In relation to surgical specialties, the average CPI for internal medicine is positive in all the cities analysed for 6 specialties (vascular surgery, cardiovascular surgery, paediatric surgery, thoracic surgery, neurosurgery and otorhinolaryngology) and for 2 more specialties in 4 of the 5 cities analysed (maxillofacial surgery and urology).

If we analyse the changes over the years by city (Table 2 and Annex B, Supplementary Figure 1) of the number of specialties for which internal medicine has a positive CPI, we can see that in Barcelona it has progressed from 69% of specialties in 2020 to 74% in 2024, in Madrid it has always been above 80% of specialties except in 2024 (68%). In Seville, it goes from 71% of the specialities in 2020 to 76% in 2023, falling to 67% in 2024. In Valencia, it varies between 62% of the specialities (years 2020 and 2023) and 76% (year 2021). Finally, Zaragoza has the greatest variability, with figures ranging from 54% (year 2023) to 82% (year 2022).

Number and percentage of specialties for which internal medicine has a positive competitive preference index (CPI) by city and year.

| City | Percentage of positive CPINumber of specialties for which the CPI for internal medicine is higher than the rest/total specialties | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||||||

| Barcelona | 69% | 29/42 | 71% | 30/42 | 74% | 32/43 | 72% | 31/43 | 74% | 32/43 |

| Madrid | 88% | 38/43 | 81% | 35/43 | 84% | 36/43 | 89% | 39/44 | 68% | 30/44 |

| Seville | 71% | 27/38 | 73% | 30/41 | 72% | 29/40 | 76% | 31/41 | 67% | 26/39 |

| Valencia | 62% | 24/39 | 76% | 29/38 | 70% | 28/40 | 62% | 24/39 | 72% | 29/40 |

| Zaragoza | 77% | 30/39 | 62% | 23/37 | 82% | 33/40 | 54% | 22/41 | 56% | 23/41 |

CPI: Competitive Preference Index.

The best percentage by city and year is highlighted in bold, the worst in italics.

If we analyse the data by type of specialty over the years (Table 3 and Appendix B Supplementary Figure 2), in relation to laboratory /central services specialties, the CPI for internal medicine has always been above 80% of specialties in all the cities analysed. With regard to medical specialties, it has been in ranges between 55% of specialties in Zaragoza in 2023 and 86% in Madrid in 2023.

Percentage of specialties for which internal medicine has a positive competitive preference index (CPI) by city and year, grouped by specialty type.

| City | Percentage of positive CPI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| Laboratories/Central services | |||||

| Barcelona | 88% | 88% | 88% | 86% | 86% |

| Madrid | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 89% |

| Seville | 83% | 100% | 86% | 100% | 80% |

| Valencia | 83% | 83% | 83% | 83% | 83% |

| Zaragoza | 83% | 80% | 100% | 83% | 83% |

| Medical | |||||

| Barcelona | 65% | 75% | 76% | 73% | 77% |

| Madrid | 80% | 75% | 80% | 86% | 67% |

| Seville | 79% | 74% | 74% | 85% | 75% |

| Valencia | 63% | 74% | 70% | 60% | 70% |

| Zaragoza | 80% | 70% | 81% | 55% | 59% |

| Surgical | |||||

| Barcelona | 64% | 57% | 64% | 64% | 64% |

| Madrid | 93% | 79% | 79% | 86% | 57% |

| Seville | 54% | 57% | 64% | 50% | 50% |

| Valencia | 50% | 77% | 64% | 54% | 71% |

| Zaragoza | 69% | 42% | 77% | 38% | 38% |

CPI: Competitive Preference Index.

The best percentage by city and year is highlighted in bold, the worst in italics.

For surgical specialties, the range is between 38% of Zaragoza in 2023 and 2024, and 93% of Madrid's specialties in 2020.

Finally, in the analysis by cities according to type of specialty (Table 4), the percentage of specialties for which internal medicine has a positive average CPI between 2020 and 2024 was positive for 84% of specialties (37 out of 44) in Madrid, 71% (30 out of 42) in Seville, 70% (31 out of 44) in Barcelona, 70% (28 out of 40) in Valencia and 62% (26 out of 42) in Zaragoza.

Number and percentage of specialties for which internal medicine has a positive average competitive preference index (CPI) over the last 4 years by type of specialty and city.

| Specialties | Percentage of positive CPINumber of specialties for which the CPI for internal medicine is higher than the rest/total specialties | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | Madrid | Seville | Valencia | Zaragoza | ||||||

| Laboratories/Central services | 88% | 7/8 | 100% | 9/9 | 100% | 8/8 | 83% | 5/6 | 83% | 5/6 |

| Medical | 73% | 16/22 | 81% | 17/21 | 80% | 16/20 | 70% | 14/20 | 64% | 14/22 |

| Surgical | 57% | 8/14 | 79% | 11/14 | 43% | 6/14 | 64% | 9/14 | 50% | 7/14 |

| Total | 70% | 31/44 | 84% | 37/44 | 71% | 30/42 | 70% | 28/40 | 62% | 26/42 |

CPI: Competitive Preference Index.

The results obtained for internal medicine in the CPI calculation in comparison with the other specialties, where positive results are obtained in comparison with the majority of specialties and in most of the cities analysed, lead us to conclude that the specialty of internal medicine has a notable attractiveness among medical residency (MIR) candidates, especially when compared with laboratory/central services and medical specialties.

In terms of medical specialties with which internal medicine is in greater competition due to their more similar characteristics, positive CPI percentages stand out for up to 84% of specialties in Madrid, 71% in Seville and 70% in Barcelona and Valencia, the 4 cities with the largest populations and which concentrate the largest number of hospital beds in Spain, with internal medicine services of long tradition and prestige, both at the level of care and at the level of teaching and research.

The fact that the specialty of internal medicine is exhausted towards the middle of the days of choice over the years, with an average number of 5089 in the cities analysed during the years 2020–2024, contrasts with the fact that, according to the indicator devised, it presents a positive CPI in relation to the majority of them, with results persistently above 70% of specialties in cities such as Madrid, Barcelona and Seville in the years 2021–2023.

Among the cities analysed, Madrid stands out as the one with the best results over the years, with percentages of up to 89% of specialties with a positive CPI in 2023, i.e. leading in 39 of the 44 eligible specialties. In Seville, on the other hand, a positive CPI in 2023 was achieved in 76% of the specialties analysed, i.e. 31 of the 41 eligible specialties. On the other hand, Zaragoza is the worst performer, with a positive CPI in 2023 for 54% of the specialties analysed, i.e. 22 of the 41 eligible specialties.

The fact that the number of vacancies in internal medicine has been twice as high as the average number of vacancies in the other specialties in the last 4 calls for applications reflects the needs of the Spanish health system to cope with the changes in the population, which, like other health systems comparable to Spain, requires generalist specialists to provide holistic and comprehensive quality care to the population,12–14 in particular, GPs, paediatricians and internists, the 3 specialties with the highest number of vacancies in medical residency (MIR). This high demand is not required by the other specialties, which more easily fill an average of 173 vacancies. This factor gives special relevance to the fact that they have not only maintained but also improved their attractiveness with respect to other specialties. All the more so when we consider that the criteria for choosing a residency have evolved in recent years, and that the level of effort and dedication usually associated with this specialty is a factor that does not seem to contribute to its attractiveness.

A survey15 among internal medicine residents conducted by the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI), with 194 participants showed that for 86% of those surveyed, internal medicine was their first choice. In fact, 82% would choose it again and 84% believe that the duration is adequate. In addition, the majority believed that the care and technical capacity of their centre is adequate (56.7%) or very adequate (26.8%). The most highly valued aspects of the residency were paid learning (83.0%) and working in a team (49%); however, the most negative aspects were job insecurity at the end of the residency (73.7%) and the lack of supervision during the residency (37.1%).

The fact that the population, both in Spain and in neighbouring countries, is ageing, with the associated polypathology and polypharmacy, means that the training of GPs16,17 is essential, both from the point of view of the most appropriate care for the patient and from the point of view of the sustainability of the public health system.18,19 In this respect, the work carried out by the national internal medicine committee should be highlighted. In recent years, it has drawn up a proposal for a new training programme for the specialty, which reflects the adaptation of the specialty to current health care needs and seeks to adapt training to this reality. It thus takes into account the need for residents to acquire the necessary skills in the new care settings that have emerged in recent years, such as rapid diagnosis units, day hospital, home hospitalisation, palliative care units, heart failure units, cardiovascular risk units, shared care, etc. Although this programme is pending approval by the Ministry of Health, it has already been presented at congresses and in the literature20 and is a clear commitment to the modernisation of the specialty.

Comparing internal medicine with the other major general adult specialty, general practitioner (GP), the CPI between 2020 and 2024 for internal medicine is positive in Seville and Valencia, negative in Barcelona, Madrid and Zaragoza, highlighting that the results for GPs have progressively improved over the years, with a positive CPI for internal medicine in 4 of the 5 cities in 2023 (Appendix B, Table 1 of the Supplementary material).

One of the limitations of the constructed indicator is that its results are not consistent when comparing territories with specialties with a reduced number of vacancies, as occurs in rural areas, since, as there are few vacancies available in each specialty, the choice may be due to extreme criteria that make the comparative analysis unreliable. However, the choice of the 5 most populous cities for this study, where there are a significant number of vacancies in each specialty, means that the comparison is more robust.

With regard to comparison with other similar studies20–22 that use other indicators, these have been carried out comparing specialties such as endocrinology or GP with the rest, but there are no analyses with the specialty of internal medicine.

On the other hand, this study does not take into account the resignations that occur once candidates have chosen a residency position, but if we analyse the data published on the website of the Ministry of Health on the resignations of candidates between 2018 and 2021,11 we can see that internal medicine has a percentage of resignations ranging from 2.9% to 4.3% of the total, in line with its level of vacancies, which, as explained above, amounts to 4.8% of the total number of vacancies offered.

It should also be noted that this indicator can be used to compare any of the specialties offered in medical residency (MIR) and that this analysis can continue to be applied in future calls for applications.

In short, the highly variable offer among the different medical residency (MIR) specialties must be taken into account in any analysis of the attractiveness of a specialty.10 The indicator developed aims to highlight this reality, so that such considerations can be made on the basis of objective data.

Finally, it is important to highlight the importance of general practice in the Spanish public health system, as it provides health care to the population with a holistic and comprehensive approach, highlighting the fact that internal medicine is an attractive specialty for medical residency (MIR) candidates.

ConclusionsInternal medicine has a positive CPI throughout the years 2020–2024 compared to most specialities, especially compared to laboratory/central services and medical specialties.

Internal medicine is an attractive specialty among residents (MIRs), especially in Madrid, Seville, Barcelona and Valencia, where it has a positive CPI compared to 70% or more of the specialties between 2020 and 2024.

The best CPI result is in the year 2023 in Madrid, which is positive for 89% of the specialties, i.e. 39 of the 44 eligible specialties.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe data for this work were obtained from the Specialised Health Training section of the Ministry of Health website.

FundingThis work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Ermengol Coma, Francesc Fina, Eulàlia Dalmau-Matarrodona and Núria Nadal for their contribution to the development of the indicator and the study.