We sought to identify preoperative cardiac abnormalities with routine preoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) associated with postoperative mortality in elderly patients undergoing hip fractures surgery, in order to provide reference for focused TTE.

MethodsIn this retrospective study, a total of 669 elderly patients (age over 65 years) undergoing hip fractures surgery were included, of which 58 (8.7%) died within one-year after discharge. Cox regression analysis models were used to identify the prognostic cardiac abnormalities of postoperative mortality.

ResultsUnivariate analysis showed that age (HR 1.065, 95%CI 1.030–1.101; P<0.001), ASA score (III, IV vs. I, II) (HR 1.855, 95%CI 1.098–3.067; P=0.022), history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (HR 4.446, 95%CI 1.909–10.355; P=0.001) and atrial fibrillation (AF) (HR 3.803, 95%CI 1.803–8.024; P<0.001), presence of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)<50% (HR 5.009, 95%CI 2.151–11.665; P<0.001), left ventricular dilatation (HR 3.813, 95%CI 1.730–8.403; P=0.001), pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP)>25mmHg (HR 4.388, 95%CI 2.492–7.725; P<0.001), moderate–severe aortic valve stenosis (AS) (HR 4.702, 95%CI 1.471–15.035; P=0.009) were the dominant predictors of mortality within one-year. The presence of LVEF<50%, left ventricular dilatation and elevated PASP were proved to be the independent predictors of one-year mortality in elderly patients in multivariate analysis.

ConclusionCardiac abnormalities derived from preoperative TTE, namely LVEF<50%, AS, left ventricular dilatation and elevated PASP had prognostic value for elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. We consider that these indices would be clinically important regarding the preoperative cardiac risk assessment of elderly hip fracture, which may be assessed in the focused TTE.

Se buscó identificar las alteraciones cardiacas preoperatorias con ecocardiografía transtorácica (ETT) asociadas a la mortalidad postoperatoria en pacientes ancianos sometidos a cirugía de fractura de cadera, con el fin de proporcionar referencia para la ETT focalizada.

MétodosEn este estudio retrospectivo se incluyó un total de 669 pacientes ancianos (mayores de 65 años) sometidos a cirugía de fractura de cadera, de los cuales 58 (8,7%) fallecieron en un año tras el alta hospitalaria. Se utilizaron modelos de análisis de regresión de Cox para identificar las anomalías cardiacas con valor pronóstico de la mortalidad postoperatoria.

ResultadosEl análisis univariado mostro que la edad (HR: 1,065; IC95%: 1,030-1,101; p < 0,001), puntuación ASA (III, IV VS. I, II) (HR: 1,855; IC95%: 1,098-3,067; p = 0,022), antecedente de enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) (HR: 4,446; IC95%: 1,909-10,355; p = 0,001) y fibrilación auricular (FA) (HR: 3,803; IC95%: 1,803-8,024; p < 0,001), presencia de fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo (FEVI) < 50% (HR: 5,009; IC95%: 2,151-11,665; p < 0,001), dilatación del ventrículo izquierdo (HR: 3,813; IC95% 1,730-8,403; p = 0,001), presión sistólica arterial pulmonar (PSAP) > 25 mmHg (HR: 4,388; IC95%: 2,492-7,725; p < 0,001), estenosis valvular aórtica (EA) moderada grave (HR: 4,702; IC95% 1,471-15,035; p = 0,009) fueron los predictores dominantes de mortalidad en el plazo de un año. La presencia de FEVI < 50%, dilatación del ventrículo izquierdo y PSAP elevada resultaron ser los predictores independientes de mortalidad a un año en pacientes ancianos en el análisis multivariante.

ConclusiónLas anormalidades cardiacas derivadas de la ETT preoperatoria, a saber, FEVI < 50%, EA, dilatación del ventrículo izquierdo y PSAP elevada tuvieron valor pronóstico para los pacientes ancianos sometidos a cirugía de fractura de cadera. Consideramos que estos índices pueden ser evaluados en el ETT enfocado.

Worldwide, the number of individuals with hip fractures is rapidly increasing due to the increasing age of the population. Prior studies documented that most cases who experienced hip fractures were aged 65 years and older. Furthermore, hip fractures in elderly patients is associated with an increased morbidity, mortality, and loss of functional independence, which is becoming a public health burden.1,2 At present, surgical repair is the standard of care, even for the frail patients. In addition, prompt orthopedic intervention within 48h of fractures significantly improved prognosis and reduced mortality.3,4

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) provides a qualitative and quantitative assessment of cardiac morphology and function, helping to diagnose specific cardiac pathologies, such as cardiac failure, valvulopathies and hemodynamic status, which cannot be reliably diagnosed through clinical examination.2 A systematic review of echocardiography demonstrated that underlying cardiac pathology detected by echocardiography may alter the clinical evaluation in 17–78% of cases. Therefore, identifying cardiac abnormalities before surgery can improve perioperative management and reduce postoperative morbidity and mortality.5 However, there is also evidence that delaying surgery increases postoperative mortality, constraining the time available for pre-operative investigations.6 Studies have suggested that preoperative TTE may delay surgical repair, thereby increasing the risk of mortality and complications.7–10

Focused TTE is a goal-directed, abbreviated form of echocardiography, which enhances bedside clinical evaluation and guides acute medical decisions without delaying surgery.11 Focused TTE changes clinical evaluation and management by guiding preoperative intravascular volume replacement, and rationalizing the use of invasive monitoring, diuretics, avoid fluid overload, vasopressor infusions and planned postoperative intensive care.6 But the cardiac abnormalities focused TTE should focused on are not yet clear and unified. We sought to identify echocardiographic prognostic indices for elderly patients after hip fractures surgery by evaluating the relationship between cardiac abnormalities derived from preoperative TTE and postoperative mortality, in order to provide reference for focused TTE.

Materials and methodsStudy design and patientsThis retrospective study was based on the data of elderly hip fractures cases aged over 65 years who were admitted at Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People's Hospital between Jun 2019 and August 2022. We screened our hospital electronic database for the patients diagnosed with hip fractures who underwent surgery. Patients with polytrauma, pathological fractures, periprosthetic fractures, history of malignant tumor, and patients without complete medical records or preoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) were excluded. The local ethics committee approved this research. In the process of the study, researchers covered all data confidentiality and compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We retrospectively extracted the patients’ impact data without any intervention measures.

Data collectionData for all enrolled patients were collected from the electronic medical records of the hospital. The characteristics those were considered were age, gender, fracture type (femoral neck, intertrochanteric or subtrochanteric), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, surgery type (total hip arthroplasty, hemiarthroplasty, or proximal femoral nail anti-rotation) and preoperative medical comorbidities including: (1) hypertension, (2) coronary artery disease (CAD, either documented previous angina, myocardial infarction, abnormal coronary angiogram or coronary revascularization), (3) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, use of bronchodilators or steroids), (4) cerebrovascular disease (either documented previous embolic, thrombotic or hemorrhagic cerebral event), (5) diabetes mellitus requiring oral hypoglycemic or insulin therapy, (6) chronic kidney disease (CKD, persistent elevated creatinine or requirement for intermittent peritoneal or hemodialysis), (7) documented atrial fibrillation (AF).6

Preoperative transthoracic echocardiographyAll patients underwent preoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). A detailed data was sorted from echocardiography reports including left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular wall thickness, left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular end diastolic diameter (LVEDD), pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP), valvular heart disease (stenosis, regurgitation or insufficiency), left ventricular outflow tract pressure gradient, pericardial effusion (PE).

Major TTE abnormalities were defined as: (1) LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF<50%); (2) Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), defined by ratio of posterior wall/septal thickness<1.1; (3) Left atrial dilatation (LAD≥40mm); (4) Left ventricular dilatation (LVEDD≥55mm in male; LVEDD≥50mm in female); (5) PASP>25mmHg; (6) Moderate–severe aortic valve stenosis (AS), defined by a mean pressure gradient>40mmHg and/or an indexed aortic valvular area<1cm2/m2; (7) Moderate–severe mitral valve stenosis (MS), defined by an indexed mitral valvular area<1cm2/m2; (8) Moderate-severe aortic or mitral valvular regurgitation; (9) Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), defined by a peak pressure gradient>30mmHg; (10) PE.12

Definition of outcomeThe outcome was defined as postoperative all-cause mortality within one year after discharge. Verification of death was acquired from hospital databases and telephone follow-up.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation [SD] for continuous variables, frequencies, and proportions for categorical variables) were calculated. Continuous data was compared using Student's t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, Kruskal–Wallis H-test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical data was analyzed using χ2 or Fisher's exact tests. To assess the association between potential explanatory factors and outcomes, Cox regression analysis was used and hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. For postoperative mortality, a univariate screen was first performed and variables with P-values<0.001 were subjected to multivariate COX regression model. Final multivariable model was determined using forward selection (LR, Likelihood Ratio) and α=0.05 significance level. Furthermore, the continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) were calculated to exactly quantify the number of patients correctly reclassified into higher or lower risk categories after adding cardiac abnormalities to a base model. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to examine the predictive performance of models for mortality. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to examine cumulative event rates, and differences between groups were tested using the log rank test. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS v.26.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and R-language 4.3.1. A two-sided P<0.05 was accepted to indicate a statistically significant difference.

ResultsIn our study, a total of 724 elderly patients underwent hip fractures surgery between June 2019 and August 2022, of which 687 (94.9%) had preoperative TTE and 18 (2.5%) died in-hospital. A total of 669 elderly patients were included in our final analysis. The clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age of them were 78.8 (±8.0) years and 215(32.1%) cases were male. 58 cases of them died within one year after discharge, of which 12 cases (20.7%) died of COVID-19, 7 cases (12.1%) died of cerebrovascular diseases, 7 cases (12.1%) died of Alzheimer's disease,13,14 23 cases (39.6%) died from cardiovascular diseases (8 from heart failure, 10 from arrhythmia, 5 from sudden cardiac death) and 9 cases (15.5%) of unknown causes.

Baseline characteristics of elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.

| Variables | Total (N=669) | Survival (N=611) | Death (N=58) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 78.8±8.0 | 78.5±7.9 | 82.7±8.0 | <0.001 |

| 65–74 | 222 (33.2) | 211 (34.5) | 11 (19.0) | |

| 75–84 | 283 (42.3) | 260 (42.6) | 23 (39.7) | 0.003 |

| ≥85 | 164 (24.5) | 140 (22.9) | 24 (41.4) | |

| Male, n (%) | 215 (32.1) | 199 (32.6) | 16 (27.6) | 0.437 |

| Fracture type, n (%) | ||||

| Femoral neck | 365 (54.6) | 334 (54.7) | 31 (53.4) | |

| Intertrochanteric | 279 (41.7) | 253 (41.4) | 26 (44.8) | 0.798 |

| Subtrochanteric | 25 (3.7) | 24 (3.9) | 1 (1.7) | |

| ASA score, n (%) | ||||

| I | 58 (8.7) | 53 (8.7) | 5 (8.6) | |

| II | 291 (43.5) | 274 (44.8) | 17 (29.3) | 0.093 |

| III | 309 (46.2) | 274 (44.8) | 35 (60.3) | |

| IV | 11 (1.6) | 10 (1.6) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Surgery type, n (%) | ||||

| Total hip arthroplasty | 247 (36.9) | 227 (37.2) | 20 (34.5) | |

| Hemiarthroplasty | 114 (17.0) | 99 (16.2) | 15 (25.9) | 0.168 |

| Proximal femoral nail anti-rotation | 308 (46.0) | 285 (46.6) | 23 (39.7) | |

| Comorbidities on admission, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 316 (47.2) | 285 (46.6) | 31 (53.4) | 0.321 |

| Coronary artery disease | 72 (10.8) | 68 (11.1) | 4 (6.9) | 0.320 |

| COPD | 20 (3.0) | 14 (2.3) | 6 (10.3) | 0.005 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 90 (13.5) | 83 (13.6) | 51 (12.1) | 0.747 |

| Diabetes | 138 (20.6) | 124 (20.3) | 14 (24.1) | 0.489 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 18 (2.7) | 17 (2.8) | 1 (1.7) | 1 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 30 (4.5) | 22 (3.6) | 8 (13.8) | 0.003 |

| Echocardiographic abnormality, n (%) | ||||

| LVEF<50% | 19 (2.8) | 13 (2.1) | 6 (10.3) | 0.004 |

| LVH | 18 (2.7) | 17 (2.8) | 1 (1.7) | 0.726 |

| Left atrial dilatation | 72 (10.8) | 65 (10.6) | 7 (12.1) | 0.737 |

| Left ventricular dilatation | 27 (4.0) | 20 (3.3) | 7 (12.1) | 0.006 |

| PASP>25mmHg | 64 (9.6) | 47 (7.7) | 17 (29.3) | <0.001 |

| Moderate-severe AS | 9 (1.3) | 6 (1.0) | 3 (5.2) | 0.036 |

| Moderate-severe MS | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Moderate-severe aortic or mitral valve regurgitation | 11 (1.6) | 10 (1.6) | 1 (1.7) | 1 |

| LVOTO | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (1.7) | 0.239 |

| PE | 4 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (1.7) | 0.305 |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; PASP, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure; AS, aortic valve stenosis; MS, mitral valve stenosis; LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; PE, pericardial effusion.

The characteristics of patients who died or survived are listed in Supplementary Table 1. There were no significant differences in gender, fractures type and surgery type between the survivals and postoperative deaths within one year after discharge. Patients with older age and higher ASA score (III, IV vs. I, II) had a higher mortality. As to comorbidities on admission, patients with history of COPD (P=0.001) and AF (P<0.001) had a higher mortality within one year. Patients who died within one year were more likely to have LVEF<50% (10.3% vs. 2.1%, P=0.004), left ventricular dilatation (12.1% vs. 3.3%, P=0.006), PASP>25mmHg (29.3% vs. 7.7%, P<0.001) and moderate-severe AS (5.2% vs. 1.0%, P=0.036) than those who survived.

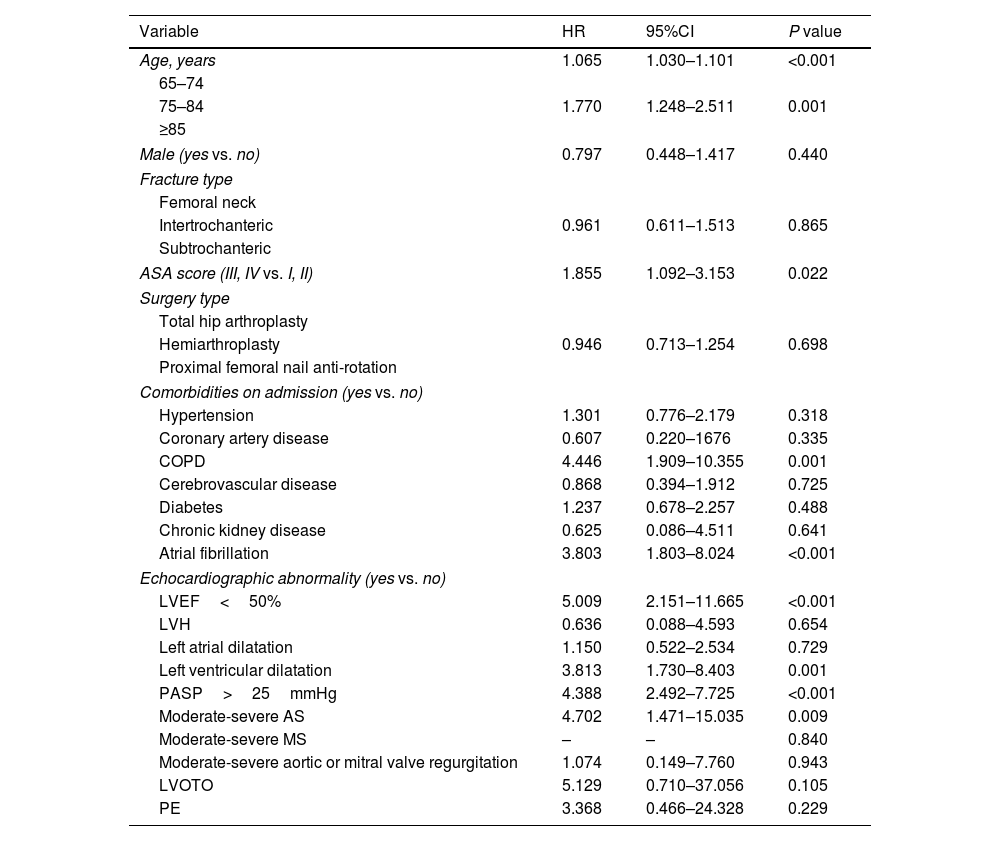

The following variables were found to be independently associated with mortality within one year in univariate COX regression analysis (Table 2): age (HR 1.065, 95%CI 1.030–1.101; P<0.001), ASA score (III, IV vs. I, II) (HR 1.855, 95%CI 1.098–3.067; P=0.022), history of COPD (HR 4.446, 95%CI 1.909–10.355; P=0.001) and AF (HR 3.803, 95%CI 1.803–8.024; P<0.001), presence of LVEF<50% (HR 5.009, 95%CI 2.151–11.665; P<0.001), left ventricular dilatation (HR 3.813, 95%CI 1.730–8.403; P=0.001), PASP>25mmHg (HR 4.388, 95%CI 2.492–7.725; P<0.001), moderate–severe AS (HR 4.702, 95%CI 1.471–15.035; P=0.009). Supplemental Table 1 shows a multivariate COX regression model including all the above factors. The presence of LVEF<50%, left ventricular dilatation and elevated PASP were proved to be the independent predictors of one-year mortality in elderly patients.

Univariate COX regression analysis for the prediction of mortality within one year.

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.065 | 1.030–1.101 | <0.001 |

| 65–74 | |||

| 75–84 | 1.770 | 1.248–2.511 | 0.001 |

| ≥85 | |||

| Male (yes vs. no) | 0.797 | 0.448–1.417 | 0.440 |

| Fracture type | |||

| Femoral neck | |||

| Intertrochanteric | 0.961 | 0.611–1.513 | 0.865 |

| Subtrochanteric | |||

| ASA score (III, IV vs. I, II) | 1.855 | 1.092–3.153 | 0.022 |

| Surgery type | |||

| Total hip arthroplasty | |||

| Hemiarthroplasty | 0.946 | 0.713–1.254 | 0.698 |

| Proximal femoral nail anti-rotation | |||

| Comorbidities on admission (yes vs. no) | |||

| Hypertension | 1.301 | 0.776–2.179 | 0.318 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.607 | 0.220–1676 | 0.335 |

| COPD | 4.446 | 1.909–10.355 | 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.868 | 0.394–1.912 | 0.725 |

| Diabetes | 1.237 | 0.678–2.257 | 0.488 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.625 | 0.086–4.511 | 0.641 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.803 | 1.803–8.024 | <0.001 |

| Echocardiographic abnormality (yes vs. no) | |||

| LVEF<50% | 5.009 | 2.151–11.665 | <0.001 |

| LVH | 0.636 | 0.088–4.593 | 0.654 |

| Left atrial dilatation | 1.150 | 0.522–2.534 | 0.729 |

| Left ventricular dilatation | 3.813 | 1.730–8.403 | 0.001 |

| PASP>25mmHg | 4.388 | 2.492–7.725 | <0.001 |

| Moderate-severe AS | 4.702 | 1.471–15.035 | 0.009 |

| Moderate-severe MS | – | – | 0.840 |

| Moderate-severe aortic or mitral valve regurgitation | 1.074 | 0.149–7.760 | 0.943 |

| LVOTO | 5.129 | 0.710–37.056 | 0.105 |

| PE | 3.368 | 0.466–24.328 | 0.229 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; PASP, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure; AS, aortic valve stenosis; MS, mitral valve stenosis; LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; PE, pericardial effusion.

To avoid the problems of overfitting and collinearity, the aforementioned significant predictors (P<0.001) (age, AF, LVEF<50% and PASP>25mmHg) were included in the multivariate COX regression analysis. Results demonstrated that age (HR 1.049, 95%CI 1.013–1.086; P=0.007), history of AF (HR 2.510, 95%CI 1.134–5.557; P=0.023), presence of LVEF<50% (HR 3.815, 95%CI 1.577–9.228; P=0.003) and PASP>25mmHg (HR 2.687, 95%CI 1.449–4.984; P=0.002) maintained the predictive value of mortality within one-year (Table 3). Moreover, model 1(including age, AF, LVEF<50% and PASP>25mmHg) had significantly improved ability to reclassify patients’ risk than model 0 (including age and AF) (IDI=4.3%, P<0.001; continuous NRI=31.4%, P=0.008).

Multivariate COX regression analysis for the prediction of mortality within one year.

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 0 | |||

| Age, years | 1.059 | 1.025–1.095 | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation (yes vs. no) | 3.043 | 1.429–6.478 | 0.004 |

| Model 1 | |||

| Age, years | 1.049 | 1.013–1.086 | 0.007 |

| Atrial fibrillation (yes vs. no) | 2.510 | 1.134–5.557 | 0.023 |

| Echocardiographic abnormality (yes vs. no) | |||

| LVEF<50% | 3.815 | 1.577–9.228 | 0.003 |

| PASP>25mmHg | 2.687 | 1.449–4.984 | 0.002 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PASP, pulmonary arterial systolic.

ROC analysis showed that the area under curves (AUC) of model 1 was greater than that of model 0 (0.726 vs. 0.652, P=0.008) (Fig. 1). Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated that patients with older age, history of AF, presence of LVEF<50% and PASP>25mmHg had a higher mortality within one-year (Fig. 2).

This study found that advanced age, history of AF, COPD were the independent predictive factors of postoperative mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures surgery. Cardiac abnormalities derived from preoperative TTE, apart from LVEF<50% and AS which were commonly mentioned, left ventricular dilatation, and elevated PASP also had prognostic values for elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.

Hip fractures are common in the elderly patients and lead to increased morbidity, mortality, and medical costs.15 Timely surgical repair improves outcomes and quality of life in this population. Before surgical repair, preoperative cardiac evaluation must consider the risk-benefit ratio. TTE is a useful non-invasive investigation for screening and assessment of cardiac disease and risk. Several studies have found that preoperative TTE significantly lengthens the time to surgery and does not improve the survival of patients.7,9,16 A retrospective, nationwide cohort study in Japan demonstrated that preoperative echocardiography was not associated with reduced in-hospital mortality or postoperative complications.2 In addition, preoperative echocardiography in patients with hip fractures has been found to be associated with increased mortality at 90 days and 1 year.7,17 But, cardiac abnormality detected by preoperative TTE such as aortic stenosis or left ventricular dysfunction did alter preoperative consultations and targeting invasive monitoring to improve patient outcomes.18–20 Patients with cardiac abnormality of preoperative TTE did indeed receive different care, which avoids the occurrence of adverse events.21

In recent studies, focused TTE was found to be feasible, not to delay surgery and frequently influence diagnosis and management by identifying important cardiac disease and hemodynamic abnormalities.11,22 However, most of the articles were observational studies with inherent design flaws. A small prospectively randomized study demonstrated that preoperative focused TTE led to important changes in treatment, such as more rational use of invasive monitoring, vasopressor infusion and postoperative intensive care in patients with hip fractures.6 At present, the studies on cardiac abnormalities that focused TTE should pay attention to are not comprehensive. A prognostic study of elderly patients with intertrochanteric fractures demonstrated the predictive value of LVEF, AS, and LVEDD for one-month and one-year mortality.16 A study in China revealed the predictive value of preoperative TTE for major cardiac events and in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures and proposed cardiac abnormalities including LVEF<50% and AS.23

Consistent with previous research, our data confirmed that LVEF<50% remained predictive value for mortality in aged patients with hip fractures surgery.16,18 Another preoperative cardiac predictor that increased the mortality in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery is elevated PASP. PASP has been found to be a predictor of in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures.1 Our study suggested that PASP>25mmHg is a predictive factor for one-year mortality after adjusting for age, atrial fibrillation and LVEF<50%. The PASP elevation has been shown to be associated with fat embolism and venous thromboembolism in elderly patients.24,25 Pulmonary hypertension is a common complication of COPD and sleep apnea.26,27 In addition, direct connection between elevated PASP and right ventricular failure has been reported in a prior study.28

In addition, we found a patient with left ventricular dilatation had an increased risk of one-year mortality (HR: 3.813, 95% CI: 1.730–8.403, P=0.001). Increased LVEDD has been correlated with dilated, ischemic, or hypertensive cardiomyopathy, ventricular septal defect, and mitral/aortic regurgitation. Dilated left ventricle with a thinner myocardial wall predisposes heart to diastolic and systolic dysfunction, diminished coronary artery circulation and ventricular dysrhythmias.29 Moreover, left ventricular capacity overload can lead to pulmonary edema and lung infection. Our research also found that AS had predictive value for one-year mortality (HR: 4.702, 95% CI: 1.471–15.035, P=0.009). This may be due to hemodynamic instability. AS resulted in decreased left ventricular compliance and coronary reserve.

In our study, the presence of AF was found to be an independent preoperative cardiac risk factor of the in-one-year mortality. AF is the most encountered arrhythmia in clinical practice and its frequency significantly increases with age. Previous studies have shown a close relationship between AF and thromboembolic events, cardiac failure, decreased motor ability, depression, and cognitive impairment in elderly patients.1 Therefore, it is reasonable that patients with the presence of AF could have a higher risk of worse outcomes and mortality. In addition, our data revealed that history of COPD were associated with an increase in one-year mortality. COPD is known as a risk factor for chronic PASP elevation,24 and also is associated with respiratory failure, which may be the way it increases mortality.

LimitationThe major limitation is that this study was a single central retrospective analysis, which might be related to selection bias. We minimized the bias in patient enrollment by using data from an electronic medical record database. The patients involved were elderly patients with preoperative TTE, so our results cannot be directly applied to all patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Further multicenter, prospective studies with larger population are needed to confirm the study's results.

ConclusionOur research suggested that elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery with a history of AF and a presence of elevated PASP might require closer follow-up, a careful fluid management and anti-coagulant treatment, even without LVEF<50% or AS. We consider that these indices including LVEF, AS, LVEDD and PASP would be clinically important regarding the preoperative cardiac risk assessment of elderly hip fracture patients who are treated with surgery, which may be assessed in the focused TTE.

Authors’ contributionsWML and YG designed the study and completed the analysis and manuscript. KHF and JWZ helped with data collection and arrangement. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participateEthics committee of Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital approved this research (ethic code number: 2023-161). Our study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2008.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

FundingNo funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestsThe authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Not applicable.