The increasing prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has led to a growing interest in the investigation of new therapies. Treatment of T2DM has focused on the insulinopenia and insulin resistance. However, in the last 10 years, new lines of research have emerged for the treatment of T2DM and preclinical studies appear promising. The possibility of using these drugs in combination with other currently available drugs will enhance the antidiabetic effect and promote weight loss with fewer side effects. The data provided by post-marketing monitoring will help us to better understand their safety profile and potential long-term effects on target organs, especially the cardiovascular risk.

La creciente prevalencia de obesidad y de diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2) comporta un interés ascendente en la investigación de nuevos procedimientos. El tratamiento de la DM2 se ha centrado hasta ahora en compensar la insulinopenia y la resistencia a la insulina. Sin embargo, en los últimos 10 años se han abierto nuevas líneas de investigación en el tratamiento de la DM2, cuyos estudios en fase preclínica parecen prometedores. La posibilidad de usar estos fármacos de forma combinada con los disponibles hasta ahora (sensibilizadores a la insulina o insulinotropos) permitirá potenciar el efecto antidiabético y favorecer la reducción ponderal con menos efectos secundarios. El seguimiento poscomercialización nos ayudará a conocer mejor su perfil de seguridad y sus potenciales efectos sobre las lesiones de los órganos diana.

Diabetes mellitus (DM), particularly type 2 (DM2), is a disease which is becoming increasingly important in terms of social health due essentially to its prevalence, which has increased over the last decades in parallel with the incidence of obesity and the ageing population, and the financial impact of the growing number of people affected by this metabolic disease and its cardiovascular repercussions. At present, we are still far from a cure for either DM2 or type 1 (DM1). This is because we only partially know the mechanisms which generate both diseases. In any case, although current knowledge is much greater than a few years ago, the actual capacity to deactivate the mechanisms which destroy the β cells or render them dysfunctional, has not resulted in truly effective solutions, at least for the time being; with the exception of bariatric surgery in diabetics with a body mass index above 35kg/m2. This surgical treatment is unique, for the moment, in that it can be associated with a reversion to normoglycaemia in approximately 70–80% of operated cases, at least in the short term.1 It is also difficult for us to prevent DM2 if obesity cannot be combated in our society, and this, as is evident, is far from happening. Perhaps the most realistic option, or one which appears to have improved, is the prevention of excessive and premature mortality, especially from cardiovascular causes, in our DM2 and our DM1 patients by early, more or less intensive drug and non-drug treatment programmes for cardiovascular protection.

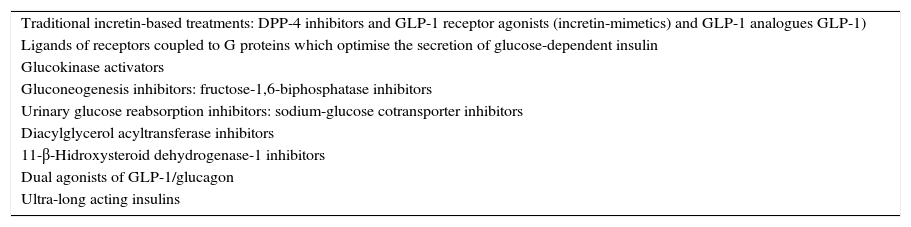

Therefore, despite the fact that recent years have seen new treatments, especially for DM2, continued pharmacotherapy research for DM over the decades to come is assured. This is because even though progress has been made in the treatment of this disease, and the concept of patients assuming self-care and responsibility has been introduced very or relatively successfully, we know that the procedures currently available are far from ideal, or at least could and must be improved. There is, therefore, room for progress, since the drugs which are available at the moment do not cure, or prevent DM2 from progressing to a requirement for insulin replacement therapy, and nor do they manage to preserve residual β function after a diagnosis of DM1. Similarly, most or practically all, the treatments available at present, usually have disadvantages of some type, such as hypoglycaemia, weight gain, and very recently, insufficient or possibly deficient, additional cardiovascular protection. The possibility has been muted recently that some of these agents might even have a negative effect on the development of cancer. For all these reasons, research into drug therapy continues and the number of molecules which are currently being investigated is indeed high. We attempt in this article to provide a brief review of some of the most relevant aspects of some of the drug groups, which in our opinion, already play or are going to play a role in the treatment of DM and in DM2 in particular (Table 1).

Pharmacological groups which are playing or are going to play a role in the treatment of diabetes mellitus.

| Traditional incretin-based treatments: DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists (incretin-mimetics) and GLP-1 analogues GLP-1) |

| Ligands of receptors coupled to G proteins which optimise the secretion of glucose-dependent insulin |

| Glucokinase activators |

| Gluconeogenesis inhibitors: fructose-1,6-biphosphatase inhibitors |

| Urinary glucose reabsorption inhibitors: sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors |

| Diacylglycerol acyltransferase inhibitors |

| 11-β-Hidroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 inhibitors |

| Dual agonists of GLP-1/glucagon |

| Ultra-long acting insulins |

DPP-4: dipeptidyl-peptidase 4; GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1.

The appearance of this group of drugs on the DM2 pharmacotherapeutic scene is very relevant. Its preclinical development took about 25 years of intensive research after the description of the incretin effect at the end of the seventies. By virtue of the incretin effect, the ingestion of foods affects the release of certain hormones from the digestive tract, the small intestine in particular, and these in turn have an effect on insulin secretion, enhancing it and adjusting its glucose- dependent insulinotropic action. This means that the effect of these treatments is primarily prandial, and that when glucose levels which are in the range of normal preprandial values are reached, no effect of additional stimulation of insulin secretion is produced. The hormone with the most relevant incretin effect, and why reference is made to glucoregulatory actions, is glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). It has been postulated that this peptide might be secreted or present reduced postprandial levels in people with DM2, and in any case, it does seem to have been more clearly demonstrated that the incretin effect itself is reduced in DM2.2 The development of this therapeutic group has been based on this fact.

The strategy for obtaining compounds with an incretin action was based on resolving a primary characteristic of GLP-1: its mean lifetime in the bloodstream is less than 3min. To that end, 2 types of solutions were implemented: the first, extending the mean lifetime of GLP-1 by inhibiting the enzyme which degrades GLP-1, dipeptidyl-peptidase 44 (DPP-4) and the second, by synthesising GLP-1 analogues with a longer mean lifetime. The DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin) are administered orally, and achieve acceptable glycaemic control with reductions of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of around 1%, with no weight gain and with negligible risk of hypoglycaemia. Its effect is mediated by an increase in circulating levels of GLP-1 and a reduction of glucagon.

The GLP-1 analogues and incretin mimetics are peptide molecules with an agonist action on the GLP-1 receptor which have a very high level of homology with GLP-1, or up to 50% with the native peptide sequence, respectively. In any case, these compounds are not degraded by DPP-4, they are given parenterally, subcutaneously, and have powerful effects in terms of glycaemic control–with reductions of HbA1c of between 1% and 2%–and they also induce considerable weight loss due to their anorexigenic effect by acting on the hypothalamic receptors of GLP-1 and, probably, due to their effect of slowing down bowel transit.3,4 The latter phenomenon is in part responsible for producing nausea and other adverse digestive effects, which temporarily, tend to appear frequently when treatments starts with these compounds. The combination of all the therapeutic effects of these new drugs results in an improved cardiovascular risk for these patients, in that a reduction in weight, lipids and blood pressure is produced.5,6 Furthermore, it is possible that there is a direct vascular effect mediated by GLP-1 receptors in the bloodstream,7,8 as well as by phenomena which are not dependent on this receptor, and which are GLP-1 9-36-dependent, a metabolite of native GLP-1 7-36.

An incretin mimetic (exenatide) which is given twice daily, or weekly in its microsphere formulation, and is long-acting release (exenatide LAR 2mg), and 2 GLP-1 analogues (liraglutide and lixisenatide), which are given in a single daily dose, are currently available for clinical use. Other similar molecules are under development (tapsoglutide and dulaglutide, amongst others), some of which have the added feature of a longer-acting effect, which would potentially enable them to be given monthly (VRS-859). From a functional perspective and based on the duration of their effect, these molecules have been categorised into two groups: short-acting, with a marked effect on gastric motility, and as a consequence, a strong postprandial component of action, such as exenatide and lixisenatide, and long-acting, with less of an component acting on gastric motility and postprandial effect; the latter would be compounds with a baseline action, such as liraglutide, exenatide LAR and dulaglutide. This type of treatment might mean that the therapy can be offered to a lot of people with DM2, because it is easily administered, there is very low or no risk of hypoglycaemia and there is less need for therapeutic adjustment and self-monitoring of capillary blood glucose than with insulin therapy.3,4

Molecules similar to GLP-1 seem to exhibit cytoprotective functions of a similar effect to that of the native molecules. In fact, experimental studies, with murine models fundamentally, indicate that the β cells present a greater degree of protection against apoptosis mechanisms, have a higher survival rate, and diverse phenomena associated with β cell differentiation and replication are stimulated by these molecules. In human models, these phenomena cannot be explored ex vivo, but there are sufficient data already available which appear to indicate that despite very consistent durability of glycaemic control, a significant percentage of these patients go on to require additional insulin treatment9 after long term medication with these drugs, which appears to indicate that the possibility of this type of treatment really altering the natural course can only occur in some patients, and for the time being, we do not know the determinants of this phenomenon.3,4 Only more prolonged follow-up and more studies designed to that end, which include additional prediction markers, will finally provide an answer to this question. A positive result in this regard could have implications beyond the treatment of DM2 and in addition to justifying the early introduction of these compounds in patients with DM2, might suggest co-treatment with insulin of people with DM1 from the onset, as is now being investigated.10

Ligands of receptors coupled to G proteinsThe future of incretin-based treatments goes beyond the use of GLP-1-like molecules or DPP-4 inhibitors, since at present, the possibility is being investigated of directly stimulating GLP-1 secretion by the intestinal L cells. In this regard, lines of research have emerged which focus on different orphan receptor ligands, such as GPR 119 and GPR 40; these are receptors coupled to G proteins which stimulate insulin secretion mediated by glucose. GPR 119 is expressed in the β cells, in the GLP-1 secreting intestinal L cells as well, and in the K cells of the stomach which secrete gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP), and responds to fatty acids and phospholipids, but its primary ligand is yet to be defined. Its occupation induces GLP-1, GIP and insulin secretion, independently from glucose. These compounds might act in synergy with DPP-4 inhibitors. Some GPR 119 agonist molecules are currently in the preclinical research phase.11–13

GPR 40 and its homologues (GPR 41, GPR 43 and GPR 120) respond to fatty acids and their agonists induce a considerable variety of cellular effects. GPR 40 is found primarily in the β cells and, to a lesser extent, in the brain, enteropancreatic tissue and the osteoclasts. The stimulation of GPR 40 by medium- and long-chain fatty acids stimulates insulin secretion, and its overexpression shows its role in the compensatory response of the β cell to a situation of high levels of circulating free fatty acids and insulin resistance.14 Several compounds are also under development.15–18

TGR 5 is another receptor similar to GPR 119, this is a biliary acid receptor which is expressed in the enteroendocrine cells of the digestive tract, the occupation of which also increases release of GLP-1.15–18 TGR 5 is also expressed in brown adipose tissue, in muscle, the gallbladder and in macrophages.19 In the latter, it can have suppressing effects of cytokine-mediated inflammatory phenomena and in brown adipose tissue and muscle, it increases the expression of deiodinase type 2, modulating energy expenditure.20 Various TGR 5 agonists are being investigated for their role in energy homeostasis, in lipid metabolism, and for their stimulating effect on GLP-1 secretion.21

Glucokinase activatorsThe glucokinase activators (GKAs) are a promising class of drugs for the treatment of DM2. Glucokinase (GK) is a key enzyme which acts as a glucose sensor in diverse tissues, in particular, the β cells of the pancreas; it is a limiting enzyme and controls the release of glucose-dependent insulin. In the liver, it regulates use of glucose, glycogen synthesis, and liver glucose production. GK regulation is complex and involves many factors, but its expression is essentially controlled by glucose in the pancreas and by insulin in the liver. The GKAs reduce glycaemic levels due to their effect of improving β cell sensory capacity to glucose, and increasing the secretion of glucose-dependent insulin. Simultaneously, the GKAs increase postprandial uptake of glucose by the liver and reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis. In addition, the GKAs appear to have anti-apoptotic effects on the β cell, and therefore this type of compound can act on three of the major defects present in DM2.

These drugs have been being developed over the past 15 years and their effect is to increase enzyme activity on coupling to the allosteric area of the enzyme, which is only present in the active form of the molecule.22,23 Typically, the GKAs exercise their hypoglycaemiant effect at an enzyme activity of around 50% of its maximum capacity, and frequently also increase the enzyme's maximum catalytic speed. This results in greater GK affinity for glucose. In some way, the compounds that have been developed to date lead to structural changes of the enzyme, which are similar to those of the activating mutations. Despite the fact that the effects produced by the GKAs imitate the phenomena observed due to GK mutations, unlike what happens with these, no pathological accumulation of hepatic glycogen is produced with the GKAs, or pathological transformation of glucose to fatty acids or triacylglycerol.

The GKAs could be very promising compounds in terms of efficacy, in achieving effects on both preprandial and postprandial glycaemia in patients with DM2 in preclinical studies and in patients with DM2.24,25 They can potentially be combined with most of the existing procedures, particularly with insulin sensitisers and incretin-based treatments. The principal disadvantages that this group of drug presents are the risk of hypoglycaemia26 and a loss of efficacy long term27; for this reason, new compounds are being assessed to circumvent these disadvantages.23 Thus, new molecules (AMG-1694, AMG-3969) are currently being investigated which increase the activity of GK, blocking its endogenous inhibitor.28 Their hypoglycaemiant activity appears to be restricted to diabetic animals and not normoglycaemic animals, therefore, these compounds open up a new anti-diabetic treatment pathway. Their effects need to be confirmed in long-term clinical studies, both in terms of durability of glycaemic control and safety profile.

Renal sodium glucose cotransporter inhibitorsRenal sodium/glucose transporter type 2 inhibitors (SGTL2) are another group of compounds which have been recently added to the therapeutic arsenal for DM2 (dapagliflozin, remogliflozin, sergliflozin, empagliflozin and canagliflozin).29–36 SGLT2 is 90% responsible for renal reabsorption of glucose. SGLT2 inhibition is of particular interest because the expression of SGLT2 is increased in the proximal tubule in diabetic patients, and reabsorption of glucose in the kidney is also high. Other potential advantages are the relatively low risk of hypoglycaemia, weight reduction and a reduction in blood pressure. SGLT2 mutations have been described in patients with renal glycosuria.37 These patients do not present relevant renal function or histological alterations, which shows that pharmacological inhibition of SGLT2 can be undertaken with a relatively favourable safety profile. Dapagliflozin, which has been recently marketed in our country, shows a dose-dependent effect on glycaemic reduction and on increased glucosuria from the first day of treatment, up to a maximum dose of 100mg. Postprandial glycaemia also shows an improvement with this compound. Reductions of HbA1c of between −0.55% and −0.9% are observed, accompanied by a mean weight loss of around 3%.38 The slight reduction in blood pressure is consistent with the diuretic effect produced by this treatment. The adverse effects reported do not seem to be dose-related, and consist of a greater tendency towards genital and subclinical urinary tract infections.

There might be differences in the safety profiles and efficacy between the different molecules (dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, sergliflozin, remogliflozin, ipragliflozin, and empagliflozin, amongst others) according to their potency and action selectivity on SGLT2, and in particular on SGLT1, which are yet to be assessed long term.39 Likewise, more postmarket data are needed on a greater number of patients in order to determine their long-term safety profile.

Gluconeogenesis inhibition: fructose-1,6-biphosphatase inhibitorsExcessive production of hepatic glucose, along with its reduced uptake and metabolism in muscle, fat and the liver, results in chronic hyperglycaemia in patients with DM2. Most drugs act on insulinopenia or insulin resistance. Efforts to limit glucose production have focused on limiting gluconeogenesis. Fructose-1,6-biphosphatase (FBPase) is an enzyme which is regulated in complex and multiple ways, located in the penultimate step of the gluconeogenic pathway. FBPase is competitively inhibited by fructose-2,6-biphosphatase and is regulated by AMP, which binds to an allosteric locus of the enzyme. The first MB07803 compound is in the preclinical phase; it is currently under trial in patients with DM2, after its efficacy was demonstrated in animal models.40 This compound binds tightly to the AMP binding site of FBPase, inhibiting the enzyme. At doses of 50–200mg in humans, this compound demonstrates efficacy in reducing glycaemia with an effect which lasts for 12h after administration. However, from this 200mg dose, and in particular, at doses of 400mg, it often causes nausea.41

Diacylglycerol acyltransferase inhibitorsAcetyl-CoA diacylglycerol acyltransferase-1 (DGAT-1) is an interesting target for diabesity in which numerous pharmaceutical companies are showing an interest. Both DGAT-1 and DGAT-2 catalyse the final step in triglyceride synthesis. The effect of a DGAT-1 deficiency on energy and glucose metabolism in the agouti mouse model shows that DGAT-1 inhibitors might be useful in the treatment of diabesity. Animals treated with these compounds present weight reduction through loss of body fat, and increased energy consumption, with no changes in glycaemia levels but with reduced insulinaemia, which is indicative of improved sensitivity to insulin. Animals which are deficient in DGAT-1 show lower liver fat content and more efficient triglyceride metabolism. There are currently clinical studies with LCQ-908 which corroborate the experimental data.41–44

11-β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 inhibitorsThe 11-β-hidroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 (11-β-HSD1) inhibitors are being investigated by several pharmaceutical companies as treatment for DM2.45 In humans, 11-β-HSD1 is responsible for the conversion of cortisone to cortisol in peripheral tissue. Patients with Cushing's syndrome present increased central adiposity, insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia and hypertension, and therefore it is expected that the 11-β-HSD1 inhibitors will improve glucose homeostasis and cardiovascular risk. The most developed 11-β-HSD1 inhibitor, INCB13739, completely inhibits 11-β-HSD1 for 24h after administration.46,47 At doses of 100–200mg daily, HbA1c reductions of 0.56% are achieved, but this compound does not appear to alter weight, lipids or blood pressure.48 Several clinical trials are currently in progress.

Dual agonists of glucagon-type-1/glucagon-like peptideThere is growing interest in the dual agonists of GLP-1/glucagon. Oxyntomodulin is a coagonist of the GLP-1 receptor which generates in conjunction with GLP-1 during preproglucagon processing in the L cells of the distal digestive tract, according to the tissue specificity of the processing endoproteases. Oxyntomodulin has a GLP-1 and glucagon agonist activity.49 It is known that glucagon has lipolytic activity and induces weight loss in humans. However, glucagon has harmful effects on glucose metabolism, particularly in the prandial situation. The administration of increasing doses of oxyntomodulin and compounds with dual agonist GLP-1 and glucagon activity causes greater weight loss than that achieved at the maximum tolerable doses of GLP-1 analogues.50 Recently, a compound has been formulated by PEGylating the peptide to give it greater stability and lasting effect.51,52 In murine models, a weight loss was achieved of 26%, and a loss of adipose mass of 42%, associated with very reduced intake.53 In humans, a co-agonist is yet to be identified which is sufficiently active on both receptors, and which is effective in terms of weight loss and improved glycaemic control.

Alternatively, GLP-1 secretagogues are being investigated as well, which also promote oxyntomodulin secretion. It is anticipated that DPP-4 inhibitors will have a positive influence on the duration of the effect of oxyntomodulin.

Finally, glucagon antagonists continue to be developed: in part, in order to reduce the amount of insulin needed to suppress hepatic production of glucose.54

Insulins with ultra-long duration of actionSeveral companies are designing and developing in the clinical phase, long-acting compounds with ultra flat profiles and a potential duration of several days, with a view to enabling administration 2 or 3 times a week.55 Given the controversy a few years ago regarding a possible association with cancer and long acting insulin analogues in relation to interaction with the IGF-1 receptor in particular, development of these new molecules must comply with very strict criteria in terms of mitogenicity and genotoxicity, which must be at least the same as that of human insulin. Furthermore, metabolic safety must be at least the same or superior to that of humans regarding frequency of hypoglycaemic episodes. To date there are two compounds which have these characteristics: one of them, which is still under development, is lispro basal insulin,56 the long action of which is based on the PEGylation of lysine residue 28 of the molecule's B chain; the other, currently in very advanced stages of clinical development, is degludec insulin, an ultra-long acting basal insulin, which it might even be possible to administer at intervals above 24h.57 A recent meta-analysis comparing degludec with glargine insulin in DM2 showed similar reduction in HbA1c at 52 weeks, with fewer hypoglycaemic episodes, especially nocturnal.58 At present more data is being generated with regard to its efficacy and long-term safety profile.

New studies are exploring the use of ultra-long acting insulin, degludec, in association with GLP-1 analogues, in particular liraglutide59 for its combined basal and prandial effect, respectively, demonstrating considerable efficacy and safety.

ConclusionsThe growing prevalence of obesity and DM2 results in an overload of patients at very high short-term cardiovascular risk, and therefore there is a great amount of interest in research into new treatments for DM2. In the last decades, treatment of DM2 has focused on compensating the insulinopenia and insulin resistance which characterise this disease. However in the last 10 years, new lines of research into DM2 have been opened, with preclinical studies which appear promising. Therefore, there are research studies on new drugs aimed at improving insulinopenia with fewer side effects than the current insulinotropes (glucokinase activators, G protein-coupled receptor ligands, ultra-long acting insulins), reducing hyperglycaemia (gluconeogenesis inhibitors), and even new drugs which will act through pathways other than the usual, such as the incretinic therapies (GLP-1 analogues), urinary glucose reabsorption inhibitors (sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors) or inhibitors of other metabolic pathways with an effect on DM2 and on energy metabolism (diacylglycerol acyltransferase inhibitors, 11-β-HSD1 inhibitors). The possibility of using these drugs in combination with those available to date (insulin sensitisers or insulinotropes) will strengthen the antidiabetic effect, and enhance weight loss with fewer side effects. The data provided by postmarket monitoring will help us to know more about its long-term safety profile, and its potential effects on target organ lesions, particularly at cardiovascular level.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Puig-Domingo M, Pellitero S. Nuevos agentes terapéuticos para la diabetes tipo 2. Med Clin (Barc). 2015;144:560–565.