Major electrocardiogram abnormalities (MECG) are common in middle-aged and older individuals and could be an important factor in predicting cardiovascular events.

ObjectiveTo analyse the association between MECG (Minnesota classification) and CVE independently of classic cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), and to assess whether they improve the prediction according to the Spanish Coronary Event Risk Function (FRESCO).

Method1752 participants included in three nodes of the PREDIMED study aged between 55 and 80 years with medium or high CVRF. Mean follow-up time was 5.1 years. Cumulative CVE incidence was estimated by sex with and without MECG, and hazard ratios by sex were estimated using multivariate Cox regressions adjusted for randomization group and CCRF (FRESCO). Harrel’s C Indices, Nam d’Agostino, Net Reclassification Improvement, and Integrated Discrimination Improvement were calculated.

ResultsAt baseline, 25% of the participants shows major electrocardiogram abnormalities (AMECG). During follow-up, there were 112 cardiovascular events (16 cardiovascular deaths, 15 acute myocardial infarctions, 38 anginas, 43 strokes). MECG were significantly associated with the onset of CVE. In men, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) criteria were associated with T-wave inversion (HR: 17.88, 95% CI: 5.51−58.03, p < 0.001) and QT interval prolongation (HR: 2.41, 95% CI: 1.38−4.21, p = 0.002); in women, atrial fibrillation (HR: 5.7, 95% CI: 1.76−18.72, p = 0.006) and ST-segment depression (HR: 3.24, 95% CI: 1.36−7.71, p < 0.001) were associated. No significant improvement in MECG prediction compared to FRESCO was observed.

ConclusionsMECG are independently associated with the occurrence of CVE, but do not improve risk prediction beyond traditional risk factors.

Las alteraciones mayores del electrocardiograma (AMECG) son frecuentes en personas de mediana y avanzada edad y podrían ser un factor importante en la predicción de eventos cardiovasculares (ECV).

ObjetivoAnalizar la asociación entre AMECG (clasificación de Minnesota) y ECV independientemente de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular (FRCV) clásicos y valorar si mejoran la predicción de la función de riesgo FRESCO- Función de Riesgo Española de Acontecimientos Coronarios-.

MétodoSe incluyeron 1.752 participantes del estudio PREDIMED entre 55 y 80 años con RCV medio o alto, con una media de seguimiento de 5,1 años. Durante el periodo de seguimiento se ha estimado la incidencia acumulada de ECV por sexo y presencia de AMECG y analizado la asociación entre AMECG y ECV mediante regresión multivariante de Cox ajustadas por grupo de aleatorización y RCV (FRESCO). Para analizar la mejora en la predicción se calcularon los índices C de Harrel’s, Nam d’Agostino, Net Reclassification Improvement e Integrated Discrimination Improvement.

ResultadosAl inicio del estudio, un 25% de los participantes presentaron AMECG. Durante el seguimiento aparecieron 112 eventos cardiovasculares (16 muertes cardiovasculares, 15 infartos agudo de miocardio, 38 anginas, 43 accidentes cerebrovasculares). Las AEMCG se asociaron a una mayor probabilidad de sufrir un ECV. En hombres, las principales AMECG asociadas a la aparición de ECV fueron los criterios de hipertrofia de ventrículo izquierdo (HVE) con inversión de onda T (HR: 17,88. IC 95%: 5,51-58,03. pvalor <0,001) y el alargamiento de QT (HR: 2,41. IC 95%: 1,38-4,21. pvalor = 0,002) y en mujeres la fibrilación auricular (HR: 5,7. IC 95%: 1,76-18,72. pvalor = 0,006) y el descenso del ST (HR: 3,24. IC 95%: 1,36-7,71. pvalor <0,001). No se observó mejoría significativa en la capacidad predictiva de FRESCO al introducir las AMECG.

ConclusionesLas AMECG se asocian de manera independiente con los eventos cardiovasculares (ECV), por lo que deben ser consideradas durante el curso del proceso clínico. Sin embargo, no ofrece una mejora adicional en la predicción del riesgo cardiovascular a la proporcionada por los factores de riesgo clásicos.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in Western countries1 and its prevention is a priority public health objective.2 Quantifying an individual's risk of developing the disease, according to the presence of risk factors, allows the intensity of preventive measures to be personalised and is a preventive strategy of proven effectiveness.3

Different cardiovascular risk (CVR) calculation functions or equations have been developed from longitudinal population-based studies to predict the probability of developing CVD for a certain age group over a given period of time. Most predict risk at 10 years and in people aged 35-74.4–6 The Framingham Heart Study (FHS) equation7 has been validated in different populations other than the original one, including Spain, with data from the Registre Gironí del Cor (REGICOR).8 More recently, the Spanish Risk Function for Coronary Events (FRESCO) risk equation was designed and validated in Spain using data from 11 cohorts from seven autonomous communities.9 Both FRESCO and Framingham-REGICOR equations estimate the occurrence of CVD in a Southern European population, although the Framingham-REGICOR equation tends to overestimate the occurrence of CVD. Despite attempts to adapt CVR equations to populations with a low incidence of CVD, about 20% of CVD occurs in people for whom no CVR factors were included in the equations developed.10

Electrocardiogram abnormalities may have prognostic significance in the detection of underlying cardiovascular disease. Electrocardiogram abnormalities are classified into minor and major ECG abnormalities according to the Minnesota international coding.11 Major electrocardiogram abnormalities (MECGA) have been shown to be associated with increased CVR.12–15 MECGAs include pathological ST-segment depression (>0.05 mV), inverted T wave > of –0.5 m, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) criteria with T-wave inversion (overload pattern), right bundle branch block (RBBB), left bundle branch block (LBBB), QT interval prolongation, advanced atrioventricular block (second-degree or third-degree Mobitz II), non-specific intraventricular conduction disturbance (QRS > 110 ms), atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation.

Several studies have linked the presence of electrocardiographic abnormalities to the occurrence of fatal and non-fatal CVD.16–18 However, their potential contribution to improving individual CVR prediction has not been comprehensively evaluated.19,20

The use of a non-invasive, inexpensive and widely available diagnostic technique such as the electrocardiogram to improve the determination of CVR could be of great importance in the prevention of the disease, especially in the intermediate risk population, which accounts for the largest absolute number of CVD cases as the largest segment of the population. However, its usefulness has not been studied in the moderate/high-risk Mediterranean population, whose CVD behaviour has unique characteristics.21

The aims of our study are: a) to analyse the association between the presence of MECGAs, according to the Minnesota classification, and the occurrence of CVD in a moderate/high CVR population, b) to determine whether this association is independent of the presence of classical CVR factors (according to FRESCO) and c) to analyse its contribution to the improvement of CVD prediction.

MethodStudy design and populationThis study was conducted in a subsample of the PREvention with MEDiterranean DIet (PREDIMED) study,22,23 a prospective multicentre randomised clinical trial that included 7447 patients aged 55–80 with medium or high CVR and evaluated the effect of the Mediterranean diet in the primary prevention of CVD in three groups: 1) with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil (EVOO), 2) with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with nuts and 3) a control group recommended to follow a low-fat diet of both animal and vegetable origin. The PREDIMED study demonstrated the ability of the supplemented Mediterranean diet to reduce the risk of CVD after a median follow-up of 4.8 years. Eligible study participants were men aged 55–80 years and women aged 60–80 years, with medium or high CVR and no previous cardiovascular disease at inclusion, and with readable ECGs at all three participating centres. Inclusion criteria included individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus or the presence of at least three of the following risk factors: smoking, hypertension, high levels of very low and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, overweight or obesity, or a family history of premature coronary heart disease. The main exclusion criterion was a previous cardiovascular event. A more detailed description of the PREDIMED inclusion and exclusion criteria and the procedures used have been previously described.24

The present study included all participants included in PREDIMED in the Reus, Pamplona and Palma centres. ECGs were performed at baseline and throughout the study in all centres; patients from these 3 centres were selected because they were the only ones where these were systematically available and accessible.

Identifying the presence of major electrocardiogram abnormalitiesECG reading was performed in parallel by 3 of the authors (JPB, MJAA and MFS) according to a form previously agreed upon by 2 of the author cardiologists (FAB and MFS) and reviewed by the latter (MFS). MECGAs were considered to be those coded according to the Minnesota classification: ST-segment depression greater than 0.05 mV measured at the horizontal or descending J-point, inverted T-wave greater than or equal to –0.5 mV, LVH criteria (considering any of: RI + SIII greater than 25 mm and/or S V1 + RV5-6 greater than or equal to 35 mV and/or R of aVL ≥ 11 mm or ≥ 16 mm in the presence of anterior hemiblock) with T wave inversion (overload pattern), advanced right bundle branch block, advanced left bundle branch block, QT interval prolongation (> 470 ms in females and > 450 ms in males), advanced atrioventricular block (second or third degree Mobitz II), non-specific intraventricular conduction disturbance (QRS > 110 ms), atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation.

Cardiovascular events and monitoringWe define cardiovascular event as the presence during the study of myocardial infarction, stroke, angina and death from cardiovascular causes. Martínez-González et al. describe in detail the criteria for adjudication of cardiovascular events and death.24

Four sources of information were used to identify events: repeated contacts with participants and their family doctors, annual medical record review and consultation of the National Death Index. An expert committee, whose members were unaware of the patient’s assigned group, reviewed the event information and decided on the adjudication of the event. Only events confirmed by the adjudication committee and occurring between 25 June 2003 and 1 December 2010 were included in the analyses.

The FRESCO risk equationThe FRESCO equation for calculating CVR was developed in 2014 from a pooled analysis of 11 Spanish population cohort studies (1992–2005) involving 50,408 participants aged 35–79 years who were followed up for 10 years through medical record reviews, telephone contacts and the mortality registry. The variables used to predict CVR in the FRESCO equation are the presence of smoking, diabetes, systolic blood pressure levels, lipid profile and body mass index. Two prediction models are available for men and women: A (using age, smoking and body mass index) and B (adding systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and the presence of antihypertensive treatment).

Statistical methodsThe distribution of clinical and socio-demographic characteristics was analysed according to the presence of MECGAs in males and females. Quantitative variables were reported as mean and standard deviation and qualitative variables as number and percentage.

The cumulative incidence of CVD in people with MECGAs was calculated. Proportional hazards models by sex were performed using multivariate Cox regressions, adjusted for the randomisation group of the PREDIMED study and the risk factors of the FRESCO CVR equation.

We tested the proportionality of risk of the included variables using the graphical representation of 'Schoenfeld residuals and the phtest'. Once proportional hazards are assumed, we run Cox regression models and report hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

We use Harrells’ C-index to determine the discrimination of our models; values of this index from 0.50 to 0.75 indicate low agreement, 0.76 to 0.90 medium and 0.91–1 high. Harrells' C-index is conceptually similar to the area under the curve (AUC).

We also evaluated the Nam D'Agostino statistic as an indicator of the overall goodness of fit of the predictive models. A higher value indicates a better model fit.

Cardiovascular risk reclassificationReclassification of cardiovascular event risk was assessed by comparing CVR estimates from Cox regression models including or not MECGAs. Net Reclassification Improvement (NRI) was used to assess improvements in CVR reclassification by adding the reclassification improvements of people who experienced CVD and those who did not. Individuals are classified according to their risk in 4 categories (0−4.99%, 5−9.99%, 10−19.99% and more than 20%) and the proportion of patients who, after introducing MECGAs into the model, move to another risk category in patients with and without an event is determined. An improvement in reclassification is considered to be a patient who had a cardiovascular event and would have increased their risk after the introduction of MECGAs, or a patient who did not have a cardiovascular event and decreased their risk category after the introduction of MECGAs:

Net Reclassification Improvement:

Integrated Discrimination Improvement (IDI) was also calculated, which is defined as the change in the likelihood of a cardiovascular event when considering the introduction of a new criterion. It is formulated as:

Subgroup analyses were performed for males, females and medium CV risk individuals. Stata software (version 15, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analyses and the ggplots function of R Studio was used for cumulative incidence plots (version 11.0, RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA).

ResultsThe present study was conducted on 1752 participants (43.6% male and 56.4% female) of the PREDIMED study (23.5% of the total number of persons included in the study). The follow-up period in this subsample was 5.1 years (SD: 1.5 years) identifying 112 CVD events, 15 acute myocardial infarctions (53.3% male), 38 angina (71.1% male), 43 strokes (55.8% male) and 16 deaths from cardiovascular causes (56.3% male).

MECGAs were more common in males (27.9%) compared to females (20.9%). Among males, there was a higher prevalence of smoking (27.67 vs. 5.23%), a lower incidence of hypertension (84.44 vs. 88.51%) and a higher rate of diabetes (53.63 vs. 45.95%) compared to females. In addition, women had higher levels of total cholesterol (217.81 vs. 203.43 mg/dl in men) and HDL-cholesterol (58.87 vs. 50.36 mg/dl) and were more frequently treated with statins (52.67% vs. 42.66%) (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics at follow-up of men and women with and without MECGAs included in the study.

| Baseline characteristics | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No MECGAs | MECGAs | Total | No MECGAs | MECGAs | Total | |

| (n = 547) | (n = 212) | (n = 759) | (n = 771) | (n = 204) | (n = 975) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.94 (6.26) | 68.04 (6.16) | 66.53 (6.30) | 68.30 (5.55) | 68.78 (5.27) | 68.40 (5.50) |

| Smoker | 142 (25.95%) | 68 (32.07%) | 210 (27.67%) | 42 (4.93%) | 13 (6.37%) | 51 (5.23%) |

| Ex-smoker | 254 (46.43%) | 91 (42.92%) | 345 (45.45%) | 58 (7.26%) | 9 (4.41%) | 65 (6.66%) |

| Non-smoker | 151 (27.61%) | 53 (25.00%) | 204 (26.88%) | 719 (87.80%) | 182 (89.21%) | 859 (88.10%) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 29.12 (3.00) | 29.49 (3.35) | 30.06 (3.57) | 30.05 (3.53) | 29.84 (3.48) | 30.05 (3.50) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 202.44 (37.27) | 206.43(35.90) | 203.55 (36.92) | 216.90 (37.32) | 221.22 (37.01) | 217.81(37.28) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 50.27 (13.71) | 50.61 (12.02) | 50.36 (13.25) | 59.00 (15.74) | 58.37 (13.31) | 58.87 (15.25) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 123.61 (35.27) | 126.53 (34.09) | 124.42 (34.94) | 130.00 (35.81) | 133.57 (37.45) | 130.77 (36.19) |

| Statin treatment | 239 (43.85%) | 84 (39.62%) | 323 (42.66%) | 397 (51.69%) | 115 (56.37%) | 512 (52.67%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 147.28 (18.49) | 152.12 (19.34) | 148.60 (18.79) | 146.48 (19.98) | 148.87 (19.15) | 146.98 (19.82) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 84.80 (11.18) | 85.58 (11.89) | 85.02 (11.38) | 83.78 (10.56) | 85.73 (11.57) | 84.18(10.80) |

| HT | 431 (78.79%) | 179 (84.44%) | 610 (80.36%) | 680 (88.20%) | 183 (89.71%) | 863 (88.51%) |

| HT treatment | 393 (71.84%) | 160 (75.47%) | 553 (72.85%) | 597 (77.43%) | 168 (82.35%) | 765 (78.46%) |

| DM | 296 (54.11%) | 111 (52.36%) | 407 (53.62%) | 383 (46.76%) | 65 (41.67%) | 448 (45.95%) |

| Average follow-up time (years), mean (SD) | 5.09 (1.53) | 4.99 (1.58) | 5.06 (1.54) | 5.05 (1.62) | 5.03 (1.42) | 5.05 (1.58) |

BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; HDL cholesterol, High Density Cholesterol; LDL cholesterol, Low density Cholesterol; MECGAs, major electrocardiogram abnormalities; SD, standard deviation.

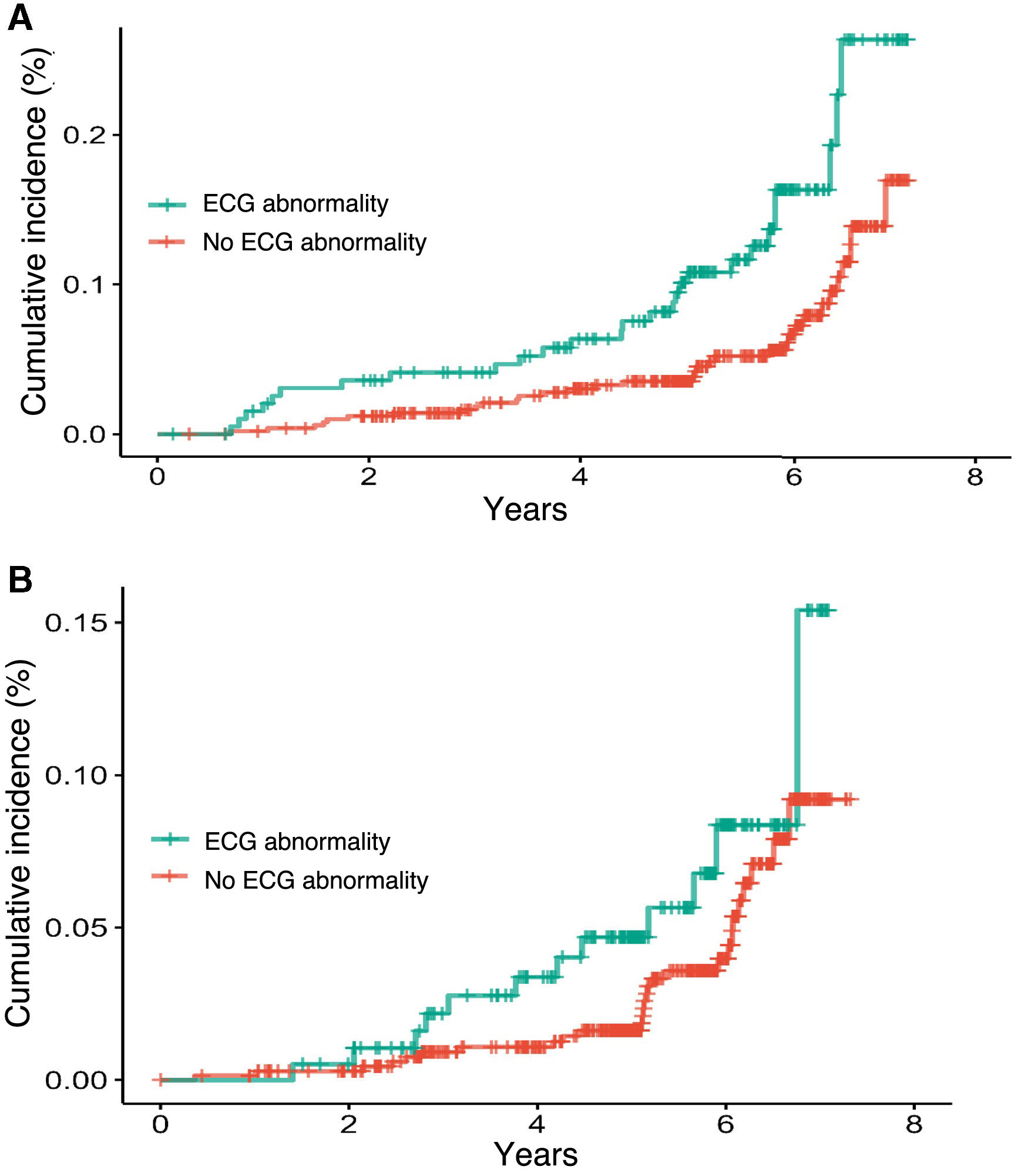

Overall, in both males and females, the prevalence of MECGAs was higher among smokers (32.07 vs. 25.95% in males and 6.37 vs. 4.93% in females). Hypertension was more common in males with MECGAs (84.44 vs. 78.79%), while in females the prevalence of hypertension was similar regardless of the presence of MECGAs (89.71 vs. 88.20%). We observed a higher cumulative incidence of CVD occurrence in subjects with MECGAs from baseline in both men and women (Fig. 1), with a larger effect size in men.

In men, we observed a statistically significant association between the presence of MECGAs and CVD both in the model adjusted for the intervention group alone (HR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.30−3.40) and in the model adjusted for other risk factors present in the FRESCO equation (HR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.26−3.50). In women, the presence of MECGAs is associated with CVD in the crude models (HR: 1.93; 95% CI: 1.02−3.64) but loses statistical significance after adjustment for other CVR factors (HR: 1.64; 95% CI: 0.83−3.25) (Table 2).

Major abnormalities according to Minnesota coding and occurrence of cardiovascular events.

| Participants | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV Event | Total | HR (95% CI) | CV Event | Total | HR (95% CI) | |

| (n = 68) | (n = 759) | (n = 44) | (n = 975) | |||

| ST depression | 1 (1.47%) | 25 (3.29%) | 0.55 (0.08−3.95) | 6 (13.63%) | 47 (4.80%) | 3.24 (1.36−7.71)** |

| Giant inverted T | 1 (1.47%) | 4 (0.53%) | 2.85 (0.39−20.72) | 0 (0%) | 7 (0.71%) | ― |

| VH with inverted T | 3 (4.41%) | 4 (0.53%) | 17.88 (5.51−58.03)*** | 1 (2.27%) | 11 (1.13%) | 2.74 (0.37−20.05) |

| RBBB | 8 (11.76%) | 75 (9.88%) | 1.20 (0.57−2.52) | 1 (2.27%) | 43 (4.41%) | 0.50 (0.07−3.67) |

| LBBB | 1 (1.47%) | 6 (0.79%) | 2.04 (0.28−14.90) | 3 (6.82%) | 31 (3.18%) | 2.71 (0.82−8.84) |

| Prolonged QT | 17 (25.00%) | 100 (13.17%) | 2.41 (1.38−4.21)** | 3 (6.82%) | 70 (7.17%) | 0.99 (0.30−3.20) |

| 2nd or 3rd degree Mobitz II AV block | 1 (1.47%) | 2 (0.26) | 39.41 (5.10−304.41)*** | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ― |

| QRS > 110 | 6 (8.82%) | 37 (4.87%) | 1.90 (0.82−4.41) | 3 (6.81%) | 24 (2.46%) | 2.31 (0.71−7.48) |

| Atrial flutter | 1 (1.47%) | 3 (0.39%) | 3.18 (0.43−23.72) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.51%) | ― |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (4.42%) | 21 (2.77%) | 2.36 (0.74−7.53) | 3 (6.82) | 14 (1.44%) | 5.75 (1.76−18.72)*** |

| Major abnormality Total | 29 (42.65%) | 212 (27.93%) | 2.10 (1.27−3.37)** | 14 (31.82%) | 204 (20.92%) | 1.9 (1.01−3.59)* |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; HR, hazard ratio; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy criteria; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

There are gender differences in MECGAs that individually contribute to this association (Table 2). In men, the criteria are LVH with inverted T (HR: 17.88; 95% CI: 5.51−58.03; p value < 0.001) (overload pattern) and QT prolongation (HR: 2.41; 95% CI: 1.38−4.21; p value = 0. 002) and in women pathological ST-segregation (HR: 3.24; 95% CI: 1.36−7.71; p-value < 0.001) and AF (HR: 5.7; 95% CI: 1.76−18.72; p-value = 0.006).

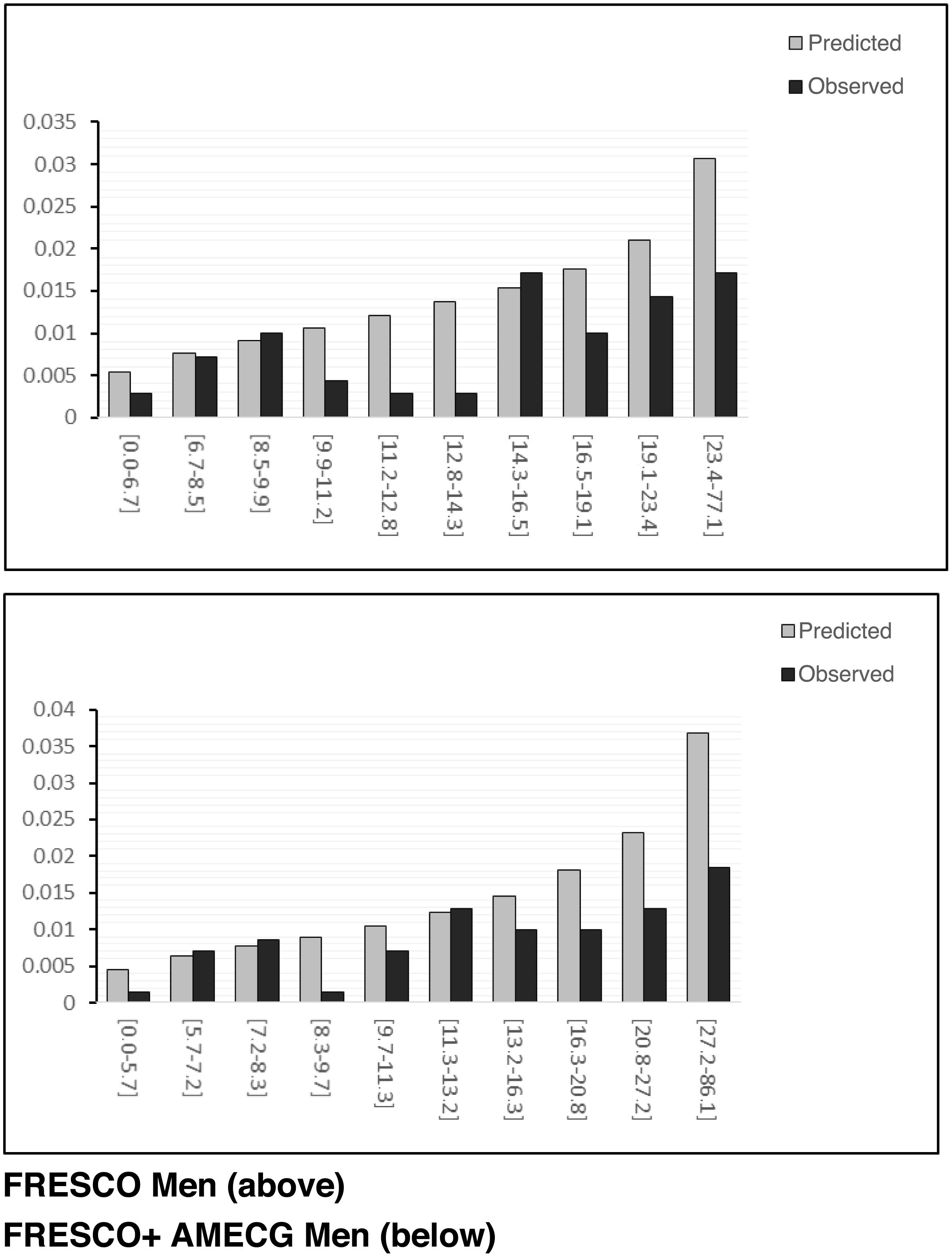

We can graphically observe the calibration of the models by comparing predicted and observed events for the different risk deciles (Fig. 2). The non-parametric Greenwood- Nam d'Agostino test assessing model calibration (comparison between predicted and observed events for the risk deciles) was statistically significant in both males and females for the FRESCO function (36.29 with p-value < 0.001) and 32.67 with p-value < 0.001) and for the FRESCO function and the occurrence of MECGAs (35.41 with p-value < 0.001 and 31.95 with p-value < 0.001) (Table 3).

Incidence of cardiovascular events, association, discriminatory power and risk reclassification according to the presence of MECGAs.

| MECGAs | FRESCO | FRESCO + MECGAs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| TN | 759 (68) | 975 (44) | ||||

| HRa major abnormalities (95% CI) | 2.10 (1.30−3.40)* | 1.93 (1.02−3.64)* | ||||

| TN | 702 (62) | 882 (39) | ||||

| HRb major abnormalities (95% CI) | 2.10 (1.26−3.50)* | 1.64 (0.83−3.25) | ||||

| Model estimates | ||||||

| C-Harrells-statistics | 0.558 (0.447−0.668) | 0.552 (0.437−0.668) | 0.592 (0.494−0.689) | 0.653 (0.543−0.764) | 0.583 (0.482−0.684) | 0.628 (0.512−0.744) |

| Nam D'Agostino goodness of fit | 36.29P value ≤ 0.001 | 32.67P value ≤ 0.001 | 35.41P value ≤ 0.001 | 31.95P value ≤ 0.001 | ||

| NRI FRESCO vs. FRESCO + MECGAs | Reference | Reference | 0.16 (0.01;0.31)* | 0.12 (– 0.07;0.32) | ||

| IDI FRESCO vs. FRESCO + MECGAs | Reference | Reference | 0.04 (0.02;0.08)* | 0.03 (– 0.02;0.08) | ||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; FRESCO, Spanish Risk Function for Cardiovascular Events; HR, hazard ratio; IDI, Integrated Discrimination Improvement; MECGAs, major electrocardiogram abnormalities; NRI, Net Reclassification Improvement; TN, total number of events.

The discriminatory power, Harrels' C-index, considering the presence of MECGAs in isolation was 0.558, 95% CI 0.447−0.668 for males and 0.552, 95% CI 0.494−0.689 for females, in both cases the value is low but not statistically significant. The discriminatory power of the FRESCO function in our sample was 0.592, 95% CI 0.494−0.689 for men and 0.653, 95% CI 0.543−0.764 for women; moderate/low values without reaching statistical significance. No improvement in prediction is observed when considering FRESCO function and MECGAs together: Harrels C-index 0.583, 95% CI 0.482−0.684 in men and 0.628, 95% CI 0.512−0.774 in women (Table 3).

Reclassification of risk and enhancement of discriminatory powerUsing the NRI index, an improvement in the reclassification of subjects with a history of CVD was observed in men (Table 4), but an increase in risk was also observed in subjects without a history of CVD, and the net improvement in reclassification after introducing the presence of MECGAs was 16.23% (95% CI: 0.01−0.31), which was statistically significant. In women, a reclassification improvement of 12.84% (95% CI 0.07−0.32) was observed, which did not reach statistical significance. The improvement in the IDI discriminatory power of the FRESCO function after introducing the presence of MECGAs is IDI: 0.04; 95% CI: 0.02−0.08 in males and 0.03; 95% CI:-0.02−0.08 in females, being statistically significant only in males.

Prediction and reclassification of cardiovascular risk in men and women using the FRESCO equation with and without MECGAs.

| Number of men | Reclassified | Percentage correctly reclassified (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in risk | Risk reduction | ||||||

| Cardiovascular risk at 10 years (FRESCO + MECGAs equation) | |||||||

| 0−4.99 | 5−9.99 | 10−19.99 | >20 | ||||

| Men WITH cardiovascular events during the follow-up period (n = 62) | |||||||

| Cardiovascular risk at 10 years (FRESCO) | |||||||

| 0−4.99 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5−9.99 | 4 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 18 | 6 | 19.35% |

| 10−19.99 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 6 | |||

| > 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Men WITHOUT cardiovascular events during the follow-up period (n = 640) | |||||||

| Cardiovascular risk at 10 years (FRESCO) | |||||||

| 0−4.99 | 139 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5−9.99 | 33 | 169 | 40 | 0 | 92 | 72 | –3.12% |

| 10-19.99 | 0 | 31 | 126 | 27 | |||

| > 20 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 42 | |||

| NRI | 16.23 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.037 | ||||||

| Number of women | Reclassified | Percentage correctly reclassified (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in risk | Risk reduction | ||||||

| Cardiovascular risk at 10 years (FRESCO + MECGAs equation) | |||||||

| Women WITH cardiovascular events during the follow-up period (n = 39) | |||||||

| Cardiovascular risk at 10 years (FRESCO) | |||||||

| 0−4.99 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5−9.99 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 7.69% |

| 10−19.99 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 6 | |||

| > 20 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Women WITHOUT cardiovascular events during the follow-up period (n = 843) | |||||||

| Cardiovascular risk at 10 years (FRESCO) | 0−4.99 | 5−9.99 | 10−19.99 | >20 | |||

| 0−4.99 | 31 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5−9.99 | 11 | 203 | 38 | 0 | 98 | 135 | 4.39% |

| 10−19.99 | 0 | 91 | 301 | 56 | |||

| > 20 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 75 | |||

| NRI | 12.08 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.228 | ||||||

FRESCO: Spanish Risk Function for Cardiovascular Events; MECGAs: major electrocardiogram abnormalities; NRI: Net Reclassification Improvement.

MECGAs were associated with an increased risk of CVD events in both men and women. However, no significant improvement in the predictive ability of the FRESCO equation is evident after the inclusion of MECGAs as a predictor.

There are differences in the frequency of occurrence of MECGAs between males and females. The prevalence of MECGAs was higher in males at 27.9% compared to 20.9% in females. Most studies report a higher prevalence of MECGAs in males,19,25 although some studies report a higher prevalence in females.26,27 In our study, the prevalence of total MECGAs was 24%. This prevalence is higher than that reported in other studies.15–18 These differences could be explained by the variability of the study populations; our study population is older and has a higher CVR than other studies.

Our results demonstrate that, in a moderate- and high-risk population without pre-existing cardiovascular disease, major ECG abnormalities are associated with an increased risk of CVD. Similarly, MECGAs have been associated with an increased incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke,2 as well as increased mortality from cardiovascular disease.26 However, not all studies find conclusive results; for example, Terho et al.27 found that MECGAs were associated with increased cardiac mortality, but not with increased CVD.

A very important aspect is the differential effect of these abnormalities on the occurrence of CVD between men and women. Liao et al. in the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project identified a higher prevalence of minor ECG abnormalities in women, but a stronger association of these abnormalities with CVD in men.25 Our study also reveals differential behaviour between men and women: in women, the abnormalities most strongly associated with the occurrence of CVD are the presence of ST-segment elevation and atrial fibrillation in women, whereas in men they are LVH with T-wave inversion and QT interval prolongation. These results highlight the need for a personalised approach to cardiovascular risk assessment and management.

These results confirmed our intention to present the prediction results of the FRESCO equation and the MECGAs separately by sex. We observed a modest improvement in CVD prediction and risk reclassification in men. However, in women, the MECGAs do not add predictive value to cardiovascular risk prediction. These findings are similar to those reported by Auer et al.,28 who found that MECGAs were associated with an increased risk of CVD and a modest improvement in CVD prediction. In this study, the inclusion of ECG abnormalities reclassified 13.6% of participants, a value similar to ours, but only in males. In our opinion, these results support the assertion of Pencina et al.29 that the NRI and IDI indices are more sensitive to small variations in discrimination than other traditional predictive assessment indicators.

These negative results observed in risk prediction in women become apparent when comparing the number of predicted and observed CVD, both using the FRESCO function and also considering the presence of MECGAs. This suggests an overestimation of CVR in women and that it does not improve when incorporating MECGAs. Overall, despite the identification of new predictors or biomarkers, the integration of these new CVR factors is limited, mainly because they do not provide substantial improvements in prediction compared to classical predictors.30

The study has some limitations, as it was conducted only in individuals from three centres of the PREDIMED study and in people with moderate and high CVR. Although the PREDIMED study collected ECG data from all patients at baseline, only three centres had ECGs accessible and available to be read. In addition, only participants with moderate and high CVR were included in the PREDIMED study. This population was selected to ensure adequate power to detect effects on the predictors studied and to ensure that the study remained powered.

However, the importance of detecting major electrocardiographic abnormalities in predicting CVR in low-risk populations should not be ruled out. A recent study showed that low-risk individuals with such abnormalities were twice as likely to experience cardiovascular death. Major predictive abnormalities include left atrial dilatation, atrial fibrillation, LVH, major Q-wave abnormalities and major ST-segment abnormalities.31

On the other hand, the sample size may have limited the statistical power to observe differences in subgroup analyses, especially in women where the incidence of CVD was lower, but also in individualised MECGA analyses, especially in the less common ones. Studies with a larger sample size and longer duration could perhaps provide more conclusive results. The strengths of the study are: its longitudinal design, the quality of data collection, especially ECG and CVD, and that it is a pioneering study in the use of improvement indices in the prediction of MECGAs in CV risk equations.

ECG is a safe, accessible and inexpensive technique. However, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations discourage the use of resting or exercise ECG screening alone for CV prevention in low-risk individuals32,33 mainly because the balance of benefits and risks of more invasive testing has not been clearly established. In our study in an intermediate to high-risk population, we observed a higher incidence of CVD in participants with MECGAs. However, because of the limited improvement in equations incorporating classical risk factors, we cannot recommend the use of ECG to support the calculation of cardiovascular risk. However, given the association we observed between some MECGAs and the subsequent occurrence of CVD, we should pay particular attention to the presence of ST-segment elevation and atrial fibrillation in women, and LVH with T-wave inversion (overload pattern) and QT interval prolongation in men, because they are more likely to develop events.

ConclusionsThe presence of MECGAs is associated with the subsequent development of CVD in medium- and high-risk Mediterranean populations, in both men and women. We observed gender differences in the changes that individually contribute to this association. The electrocardiographic criteria of LVH with T-wave inversion and QT prolongation in men and ST-segment elevation, left bundle branch block and atrial fibrillation in women are more strongly associated with CVD. Although the results of this study do not allow us to recommend the use of the ECG in addition to the CVR calculation functions (FRESCO), the increased risk associated with it makes it advisable to study the major abnormalities in the course of the clinical process on an individual basis.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that they have faithfully adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and ICH Good Clinical Practice (ICH/GCP) guidelines, in full compliance with the relevant legal authorities. The protocol and all required documents have been submitted to the Research and Ethics Committee (REC) for evaluation. Any substantial changes to the original documents have been submitted to the REC for review and compliance. Written and verbal informed consent has been obtained from all patients after they have been informed (in accordance with the Organic Law on the Protection of Personal Data).

The Research Ethics Committee of the University Clinic of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Navarra (code 50/2005), the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Balearic Islands (code 491/05), and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Sant Joan de Reus (code 0306196proj3) have participated in the ethical evaluation of this study.

FundingCarlos III Health Institute. The PREDIMED trial was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the official funding agency for biomedical research of the Spanish government, through grants awarded to research networks specifically developed for the trial (RTIC G03/140, to Ramon Estruch during 2003–2005; RTIC RD 06/0045, to Miguel A. Martínez-González during 2006–2013 and through the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición [CIBEROBN]), and through grants from the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC 06/2007), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria-Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (PI04-2239, PI 05/2584, CP06/00100, PI07/0240, PI07/1138, PI07/0954, PI 07/0473, PI10/01407, PI10/02658, PI11/01647, P11/02505, PI13/00462 and JR17/00022) funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Instituto Carlos III and also supported by funds provided by the Primary Care and Health Promotion Network (RICAPPS)RD21/0016/0009, co-financed with Next Generation EU funds, which finance the actions of the Recovery and Resilience Mechanism (RRM), Ministry of Science and Innovation (AGL-2009-13906-C02, AGL2010-22319-C03, AGL2011-23430 and SAF2016-80532-R), Fundación Mapfre 2010 (without participation in the design, implementation, analysis or interpretation of the data), Consejería de Salud de la Junta de Andalucía (PI0105/2007), División de Salud Pública del Departamento de Salud de la Generalitat de Cataluña, Generalitat Valenciana (PROMETEO 17/2017 and PROMETEO 21/2021), Fundació La Marató-TV3 (grants 294/C/2015 and 538/U/2016, without participation in the design, implementation, analysis or interpretation of the data)), Agencia Canaria de Investigación, Innovación y Sociedad de la Información-EU FEDER (PI 2007/050 and CS2011-AP-042), and Gobierno Regional de Navarra (P27/2011). The metabolomics study was supported by research grant NIDDK-R01DK 102896. Donations of olive oil, walnuts, almonds and hazelnuts were made, respectively, by the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero and Hojiblanca (Málaga, Spain), California Walnut Commission (Sacramento, California), Borges (Reus, Spain) and Morella Nuts (Reus, Spain). Prof. Jordi Salas-Salvadó is partially supported by ICREA, in the framework of the ICREA Academia programme.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.