Obstructive sleep apnoeas (OSA) are classically diagnosed in a middle-aged male snorer with overweight or obesity, observed apnoeas, daytime sleepiness and probable cardiovascular pathology. The prevalence varies according to the methodology used in different studies, but most studies show a higher prevalence in men than in women.1,2 In the field of health, inequalities between men and women have been described in the access, supply and structure of health services. These inequalities are also evident in OSA. Self-reported sleepiness scales, such as the Epworth test, have not been validated in women, and hypersomnolence manifests differently in men and women.3 Indications for diagnosis and treatment in women are extrapolated from the results of middle-aged male patients. A cluster study on a population of 1217 participants diagnosed with OSA identified a phenotype of women with moderate OSA and cardiovascular risk factors, with a high prevalence of depression, high prescription of antidepressants, anxiolytics, hypnotics and sedatives, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and weak opioids.4

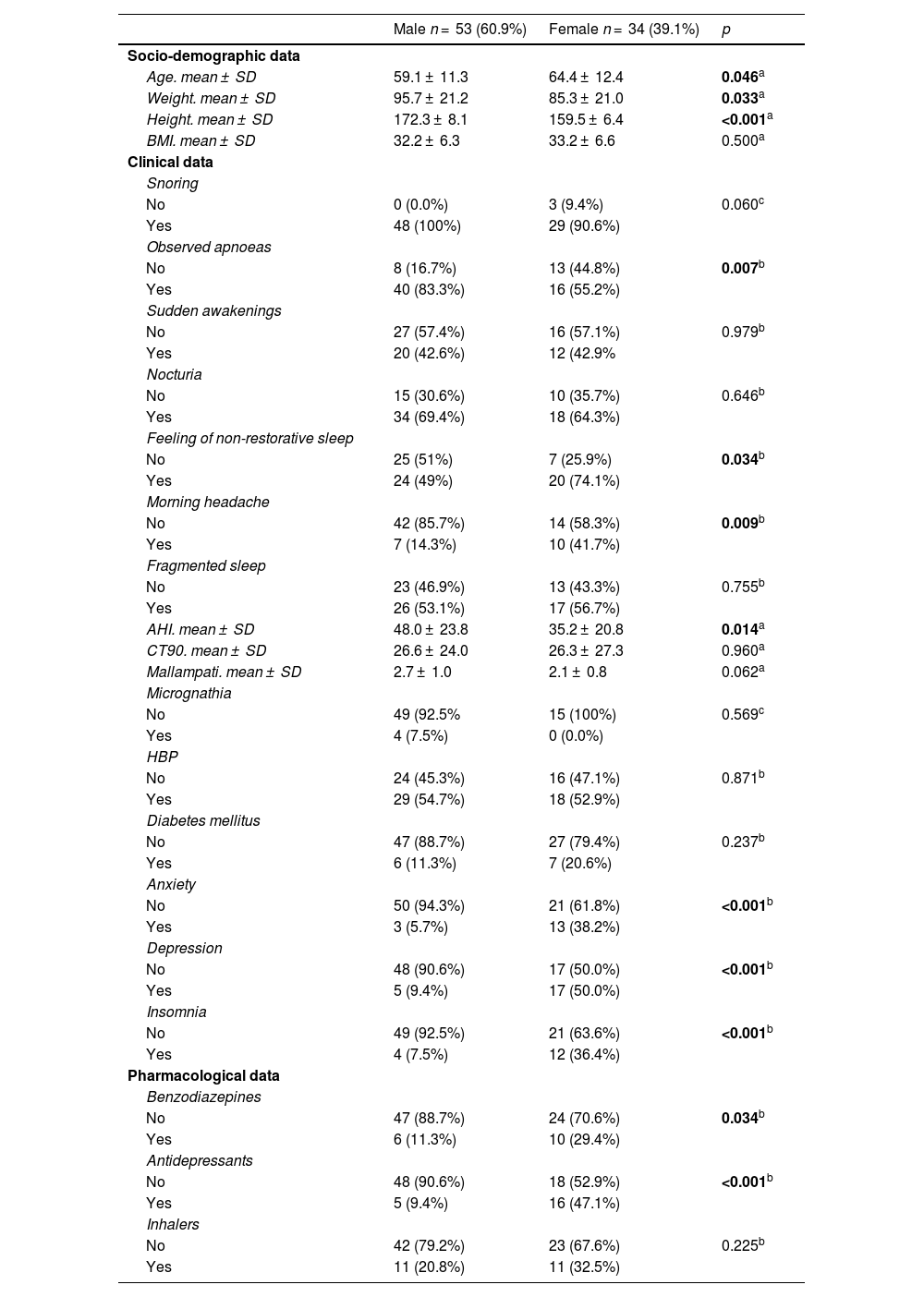

In our hospital, which has an accredited basic sleep unit and a catchment population of 190,000 inhabitants, we observed that the number of men diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and receiving treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) was three times higher than that of women. To analyse gender-related differences in the clinical profile of patients diagnosed with OSA and treated with CPAP, we conducted a retrospective, observational, descriptive study of all patients over 18 years of age who were prescribed CPAP treatment over a consecutive four-month period. The symptoms of the disease (snoring, observed apnoeas, choking episodes, nocturia, feeling of non-restorative sleep, morning headache, Epworth Sleepiness Scale), physical data (BMI; Mallampati score), comorbidities and concomitant treatments were recorded. The statistical software IBM SPSS® version 28 was used to carry out a descriptive and comparative analysis (Chi-square test and Student’s t-test), with a significance level set at 5%. A total of 87 patients (61% men) with a mean age of 61 ± 12 years were analysed. Significant differences were observed, with higher values in women for the following variables: age, feeling of non-restorative sleep, morning headache, diagnoses of anxiety and depression, insomnia, and use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants. A higher number of apnoeas was observed in men (Table 1).

Comparative analysis according to gender.

| Male n = 53 (60.9%) | Female n = 34 (39.1%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic data | |||

| Age. mean ± SD | 59.1 ± 11.3 | 64.4 ± 12.4 | 0.046a |

| Weight. mean ± SD | 95.7 ± 21.2 | 85.3 ± 21.0 | 0.033a |

| Height. mean ± SD | 172.3 ± 8.1 | 159.5 ± 6.4 | <0.001a |

| BMI. mean ± SD | 32.2 ± 6.3 | 33.2 ± 6.6 | 0.500a |

| Clinical data | |||

| Snoring | |||

| No | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (9.4%) | 0.060c |

| Yes | 48 (100%) | 29 (90.6%) | |

| Observed apnoeas | |||

| No | 8 (16.7%) | 13 (44.8%) | 0.007b |

| Yes | 40 (83.3%) | 16 (55.2%) | |

| Sudden awakenings | |||

| No | 27 (57.4%) | 16 (57.1%) | 0.979b |

| Yes | 20 (42.6%) | 12 (42.9% | |

| Nocturia | |||

| No | 15 (30.6%) | 10 (35.7%) | 0.646b |

| Yes | 34 (69.4%) | 18 (64.3%) | |

| Feeling of non-restorative sleep | |||

| No | 25 (51%) | 7 (25.9%) | 0.034b |

| Yes | 24 (49%) | 20 (74.1%) | |

| Morning headache | |||

| No | 42 (85.7%) | 14 (58.3%) | 0.009b |

| Yes | 7 (14.3%) | 10 (41.7%) | |

| Fragmented sleep | |||

| No | 23 (46.9%) | 13 (43.3%) | 0.755b |

| Yes | 26 (53.1%) | 17 (56.7%) | |

| AHI. mean ± SD | 48.0 ± 23.8 | 35.2 ± 20.8 | 0.014a |

| CT90. mean ± SD | 26.6 ± 24.0 | 26.3 ± 27.3 | 0.960a |

| Mallampati. mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.062a |

| Micrognathia | |||

| No | 49 (92.5% | 15 (100%) | 0.569c |

| Yes | 4 (7.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| HBP | |||

| No | 24 (45.3%) | 16 (47.1%) | 0.871b |

| Yes | 29 (54.7%) | 18 (52.9%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| No | 47 (88.7%) | 27 (79.4%) | 0.237b |

| Yes | 6 (11.3%) | 7 (20.6%) | |

| Anxiety | |||

| No | 50 (94.3%) | 21 (61.8%) | <0.001b |

| Yes | 3 (5.7%) | 13 (38.2%) | |

| Depression | |||

| No | 48 (90.6%) | 17 (50.0%) | <0.001b |

| Yes | 5 (9.4%) | 17 (50.0%) | |

| Insomnia | |||

| No | 49 (92.5%) | 21 (63.6%) | <0.001b |

| Yes | 4 (7.5%) | 12 (36.4%) | |

| Pharmacological data | |||

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| No | 47 (88.7%) | 24 (70.6%) | 0.034b |

| Yes | 6 (11.3%) | 10 (29.4%) | |

| Antidepressants | |||

| No | 48 (90.6%) | 18 (52.9%) | <0.001b |

| Yes | 5 (9.4%) | 16 (47.1%) | |

| Inhalers | |||

| No | 42 (79.2%) | 23 (67.6%) | 0.225b |

| Yes | 11 (20.8%) | 11 (32.5%) | |

p-values with statistical significance highlighted in bold.

Our study is consistent with recent medical literature showing that OSA presents with a different clinical phenotype in women and suggests that underdiagnosis in this group may occur. The use of new diagnostic tools and the design of clinical questionnaires that take into account the distinct female phenotype could help stratify risk and adapt the therapeutic approach in clinical practice, thereby avoiding gender bias, as recommended in the literature.5

Ethical considerationsWe followed the protocols of our centre for the conduct of this study, and it was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Fundació d'Osona per la Recerca i Educació Sanitària (FORES).

FundingNo funding has been received for the study.

We declare no conflict of interest in the present study.