Smoking affects glycemic control in individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D); however, its impact in the era of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has not been thoroughly studied.

Materials and methodsA retrospective cohort study was conducted at two centers, involving 405 T1D patients treated with multiple daily insulin injections and using CGM. The patients were matched using propensity scores based on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. HbA1c levels were analysed before and after a 2.2-year follow-up period. The analysis was performed using mixed linear regression and multivariable conditional logistic models.

ResultsThe sample included 135 smokers and 270 non-smokers, with a mean age of 47.6 years, and 50.1% were women. Both groups had a similar baseline HbA1c of 8.0 (1.5%). After follow-up, non-smokers reduced their HbA1c to 7.3 (1.1%), while smokers only reduced it to 7.7 (1.3%), 95% CI [−0.57–0.10]). The proportion of non-smokers achieving HbA1c <7% increased from 25% to 38.1%, 95% CI [0.14–0.36, whereas smokers showed no change (25.9%, 95% CI [−0.13–0.21]). Smoking was independently associated with a higher risk of not achieving HbA1c <7%, despite CGM use (odds ratio 1.89, 95% CI [1.13–3.17].

ConclusionSmoking limits the glycemic control benefits of CGM in individuals with T1D. It is crucial to include smokers in clinical trials and to develop strategies to discourage smoking in this population to maximise the benefits of diabetes technology.

El tabaquismo influye en el control glucémico de las personas con diabetes tipo 1 (DM1) sin embargo su impacto en la era de la monitorización continua de glucosa (MCG), no ha sido suficientemente estudiado.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio de cohortes retrospectivo de dos centros con 405 pacientes con DM1, tratados con múltiples dosis de insulina y usuarios de MCG, emparejados por puntajes por propensión según características sociodemográficas y clínicas Se analizaron los niveles de HbA1c antes y después de un seguimiento de 2,2 años. El análisis se realizó mediante modelos de regresión lineal mixta y logística condicional multivariable.

ResultadosLa muestra incluyó 135 fumadores y 270 no fumadores, con una edad media de 47,6 años y 50,1% mujeres. Ambos grupos comenzaron con una HbA1c similar de 8,0 (1,5%). Tras el seguimiento, los no fumadores redujeron su HbA1c a 7,3 (1,1%), mientras que los fumadores solo a 7,7 (1,3%), IC 95% [−0,57–0,10] La proporción de no fumadores con HbA1c <7% aumentó de 25% a 38,1% IC 95% [0,14–0,36], mientras que los fumadores permanecieron sin cambios (25,9%, IC 95% [−0,13–0,21]). El tabaquismo se asoció de manera independiente con un mayor riesgo de no alcanzar HbA1c<7%, a pesar del uso de MCG (odds ratio 1,89 IC 95% [1,13-3,17].

ConclusiónEl tabaquismo limita los beneficios del uso de MCG en el control glucémico de personas con DM1. Es esencial incluir a fumadores en ensayos clínicos y desarrollar estrategias para desalentar el tabaquismo en esta población, con el fin de maximizar los beneficios de la tecnología en diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes (DM1) is a chronic disease characterised by autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells, leading to absolute insulin deficiency. This condition requires meticulous management of blood glucose control to prevent long-term complications. One of the main indicators of blood glucose control is glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), which reflects average blood glucose levels over the past two to three months. Adequate HbA1c control is associated with a reduction in the risk of microvascular complications, such as retinopathy, nephropathy and diabetic neuropathy.1

Despite the importance of blood glucose control in preventing complications, not all factors affecting HbA1c levels are fully understood. Smoking, a habit known to have a negative impact on overall health, has been identified as a factor that could influence blood glucose control2 However, its specific effect on HbA1c in people with DM1 has been less studied. This is especially true in the modern era of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). CGM technology has revolutionised diabetes management by providing real-time data on glycaemic fluctuations, allowing for more precise adjustments in insulin therapy, leading to improvements in blood glucose control in both randomised clinical trials3–5 and real-world studies.6,7

Previous studies have suggested that smoking may be associated with suboptimal blood glucose control in people with DM1. It has been proposed that smoking may increase insulin resistance8 and aggravate oxidative stress,9 both of which may contribute to an increase in HbA1c. However, these studies have often not adequately controlled for confounding factors, leaving room for uncertainty about the true extent of the effect of smoking on HbA1c levels in this population.

The aim of this study is to assess the impact of active smoking on HbA1c levels in people with DM1 who are fitted with a CGM device, and to determine whether there are differences in the likelihood of achieving HbA1c within the target control range in smokers and non-smokers using a continuous glucose monitoring device.

Material and methodsA retrospective cohort study was conducted in two Spanish centres involving adults with DM1 treated with multiple doses of insulin and using CGM sensors (FreeStyle Libre®, Abbott). Subjects with other types of diabetes; those with less than 70% sensor use at the time of data extraction as recommended by international consensus10; those for whom no updated clinical information was available and for whom no HbA1c was available after sensor placement were excluded. The median duration of follow-up was 2.2 years [1.3–3.1]. This study followed the "Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology" (STROBE) guidelines11 (Appendix B Supplementary material S1). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital de La Princesa, Madrid (study number: 5084-01/2023). The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ProcedurePrior to the start of sensor use, all patients received a training session on the use of the sensor according to international recommendations.10 All patients were given written instructions on how to use the data provided by the system to make real-time adjustments to insulin doses and on the use of the Libreview cloud to retrospectively review glucose data to adjust future insulin doses. All patients were instructed to adjust their insulin doses and treatment of hypoglycaemia according to their glucose profiles and trends.

Data collectionData including socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as laboratory tests and pharmacological medication for DM1, were obtained from electronic medical records. Smoking was defined as smoking at least one cigarette, cigar or pipe per day12 (excluding e-cigarettes). A patient who previously met these criteria, but no longer smoked at the time of the study, was considered to be an ex-smoker. Sociodemographic and clinical variables collected included sex, age, duration of diabetes mellitus, body mass index (BMI), baseline HbA1c (immediately prior to sensor placement), last available HbA1c and time as a user of the CGM system. Glycosylated haemoglobin was routinely measured by liquid chromatography (ADAMS A1c HA8180 V ARKRAY®). Glucose metrics were retrieved from the Libreview platform using the FreeStyle 2 device (FreeStyle Libre 2®, Abbott) at 14 day intervals. The following variables were collected: time in range, time below <70 mg/dl and time above range, blood glucose >180 mg/dl and >250 mg/dl, number of daily readings and coefficient of glucose variation.

Socio-economic status (SES): deprivation index and average annual net income per personSocio-economic status in Spain was assessed using the deprivation index for the whole Spanish territory according to census section, 2021.13 Combines information on the following variables for each census tract: manual worker population, casual wage earner population, unemployment, persons aged 16 and over and 16−29 years with insufficient education, and main household without Internet access.

Statistical analysisAfter assessing the plausibility of the outliers, the fit to the normal distribution was assessed using statistical methods (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and graphical approaches (normal probability plot). Continuous variables that fit the normal distribution are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed variables are presented as median and 25th to 75th percentiles (p25–p75). Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages of the sample.

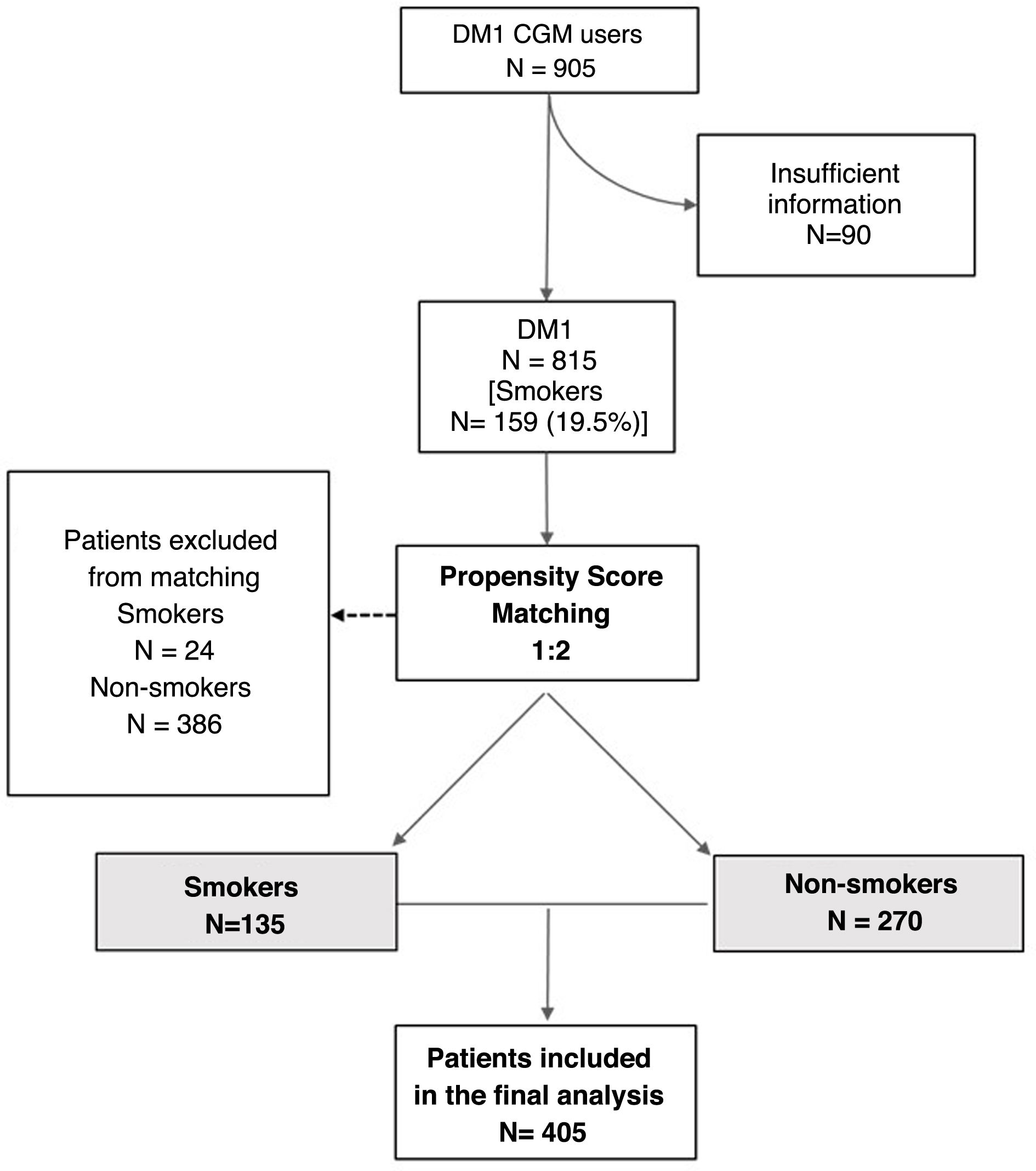

To address the lack of randomisation between study groups and minimise confounding bias, the nearest-neighbour propensity score matching method was used in a 1:2 ratio (with a calibre width of 0.05 times the SD of the logit propensity score) to estimate the effect of smoking on achieving HbA1c levels below 7%.14 Smoking propensity scores were calculated using a logistic regression model, incorporating relevant variables used in routine clinical practice in diabetes: age, sex, duration of diabetes, presence of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic nephropathy, HbA1c, BMI, insulin dose/kg/day and deprivation index. This approach made it possible to balance the probability of smoking among individuals with very similar baseline characteristics, thus allowing the effect of smoking to be studied with minimal bias.

The primary outcome aimed to verify the change in HbA1c after the placement of the CGM system in the smoking group and the control group. A linear mixed regression model analysis was performed with HbA1c as the dependent variable and with the smoking group, the interaction between elapsed time and smoking and the number of sensor readings and time as an CGM system user as fixed effects and the pairing triad as a random effect.

To study secondary outcomes, which involved achieving a target HbA1c < 7%, a conditional logistic regression model was conducted for paired data; additionally including time as a sensor user and number of daily sensor readings as covariates.

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.0.3 and STATA 17.0 statistical software. BE-Basic Edition (Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05; however, it was not used in a systematic way, with priority given to the use of the 95% confidence interval (CI) throughout the text, in accordance with international recommendations.15

ResultsAs of December 2022, the medical records of 905 people with DM1 using FreeStyle Libre 2 CGM systems were retrospectively analysed, collecting baseline clinical data at the time of CGM device placement (HbA1c included) and HbA1c at the time of data extraction.

From the initial cohort, 90 individuals were excluded because the baseline characteristics required for inclusion in the analysis were not available. From a total of 815 eligible patients, after propensity score matching by smokers 1:2 non-smokers, a final well-matched sample (Appendix B Supplementary material S2) of 405 patients was obtained, consisting of 135 smokers and 270 non-smokers (48 of whom were ex-smokers). Fig. 1 shows the flow chart.

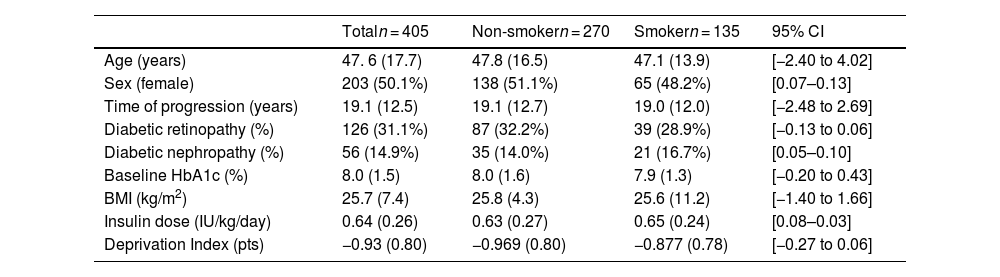

The mean age was 47.6 (17.7) years, with 203 (50.1%) women. The duration of diabetes was 19.1 (12.5) years; 126 subjects (31.1%) had diabetic retinopathy and 56 (14.9%) diabetic nephropathy. Pre-sensor HbA1c was 8.0% (1.5) and BMI was 25.7 (7.4) kg/m2. No differences in baseline variables were observed between the smoking and non-smoking groups, as shown in Table 1.

Baseline sample characteristics.

| Totaln = 405 | Non-smokern = 270 | Smokern = 135 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47. 6 (17.7) | 47.8 (16.5) | 47.1 (13.9) | [−2.40 to 4.02] |

| Sex (female) | 203 (50.1%) | 138 (51.1%) | 65 (48.2%) | [0.07–0.13] |

| Time of progression (years) | 19.1 (12.5) | 19.1 (12.7) | 19.0 (12.0) | [−2.48 to 2.69] |

| Diabetic retinopathy (%) | 126 (31.1%) | 87 (32.2%) | 39 (28.9%) | [−0.13 to 0.06] |

| Diabetic nephropathy (%) | 56 (14.9%) | 35 (14.0%) | 21 (16.7%) | [0.05–0.10] |

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 8.0 (1.5) | 8.0 (1.6) | 7.9 (1.3) | [−0.20 to 0.43] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 (7.4) | 25.8 (4.3) | 25.6 (11.2) | [−1.40 to 1.66] |

| Insulin dose (IU/kg/day) | 0.64 (0.26) | 0.63 (0.27) | 0.65 (0.24) | [0.08–0.03] |

| Deprivation Index (pts) | −0.93 (0.80) | −0.969 (0.80) | −0.877 (0.78) | [−0.27 to 0.06] |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval of the differences between the smoking and non-smoking group.

Baseline and stratified variables in the group of smokers and non-smokers.

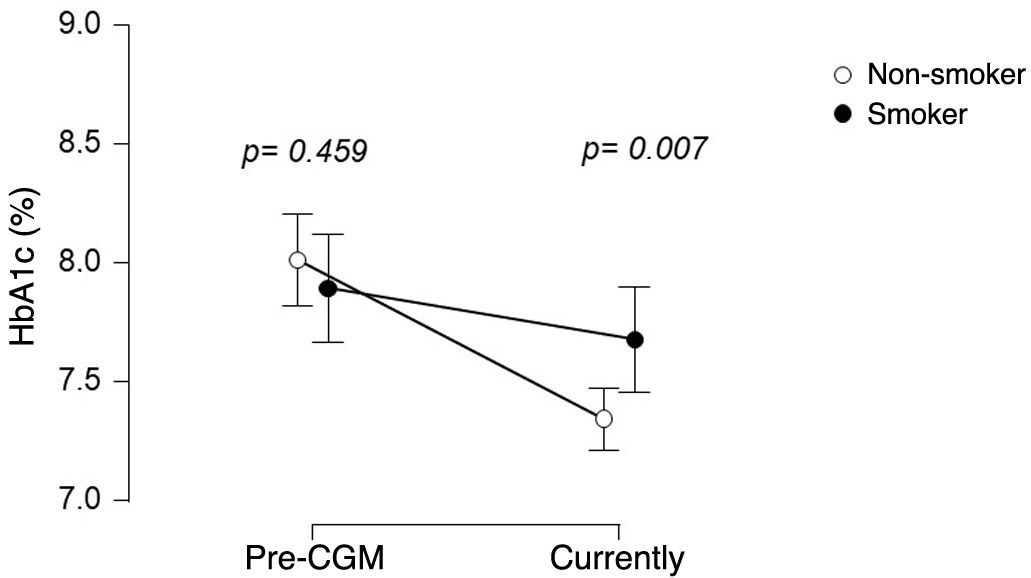

HbA1c was assessed after a follow-up of 2.2 years [1.3–3.1] after CGM device placement. Before sensor placement, HbA1c levels were 7.9 (1.3%) in the smoking group and 8.0 (1.6%) in the non-smoking group, with no difference between the two groups (CI 95% [−0.20 to 0.43]) After sensor placement, HbA1c was 7.7 (1.3%) in smokers and 7.3 (1.1%) in non-smokers (CI 95% difference [−0.57 to 0.10]). Fig. 2 the evolution of HbA1c in both groups. The median number of daily sensor readings at the time of data collection was 9 (6–14), with no difference between smokers: 9 (6–15) and non-smokers: 9 (6–14), CI 95% [−1.9 to 1.9].

Linear mixed regression modelling for longitudinal data revealed that smoking limits HbA1c improvement after sensor placement. A reduction in HbA1c of 0.66% CI 95% [−0.89 to −0.44] was observed after device installation, and that a higher number of sensor readings was associated with a more significant decrease in HbA1c (® = −0.02; 95% CI [−0.03 to −0.01] per daily sensor reading). No relevant influence of sensor wear time on HbA1c change was detected (® = 0.01; 95%CI [−0.05 to 0.08] per year of sensor wear). Furthermore, an interaction between smoking and HbA1c was observed (® = 0.44, 95% CI 95% [0.06–0.82]), indicating that changes in HbA1c differs between smokers and non-smokers, with the reduction in HbA1c being less significant in smokers.

The efficacy of the CGM in the group of ex-smokers was very similar to that of never smokers, as shown in Appendix B Supplementary material S3. Glucose metrics obtained by downloading sensor data were also analysed. In non-smokers, 63% (53–73%) of the time was in the 70–180 mg/dl range, compared with 59% (47–70%) in smokers, with a CI 95% [–7.8 to –0.2]. The TAR > 180 mg/dl was 35% (24-46%) in smokers and 32% (22-43%) in non-smokers, with a 95% CI 95% [−1.7 to 7.7]. The TAR > 250 mg/dl showed a slight tendency to be higher in smokers (8% [4–19%]) compared to non-smokers (7% [3–14%]), with a 95% CI 95% [−1.7 to 3.7]. Time below range (<70 mg/dl) was similar between smokers (3% [2–7%]) and non-smokers (3% [1–7%]), with a 95% CI 95% [−0.99 to 0.99]. There were also no significant differences in the coefficient of variation between smokers (37.8% [33.2–42.8%]) and non-smokers (36.7% [32.1–41.4%]), with a 95% CI 95% [−0.72 to 2.92].

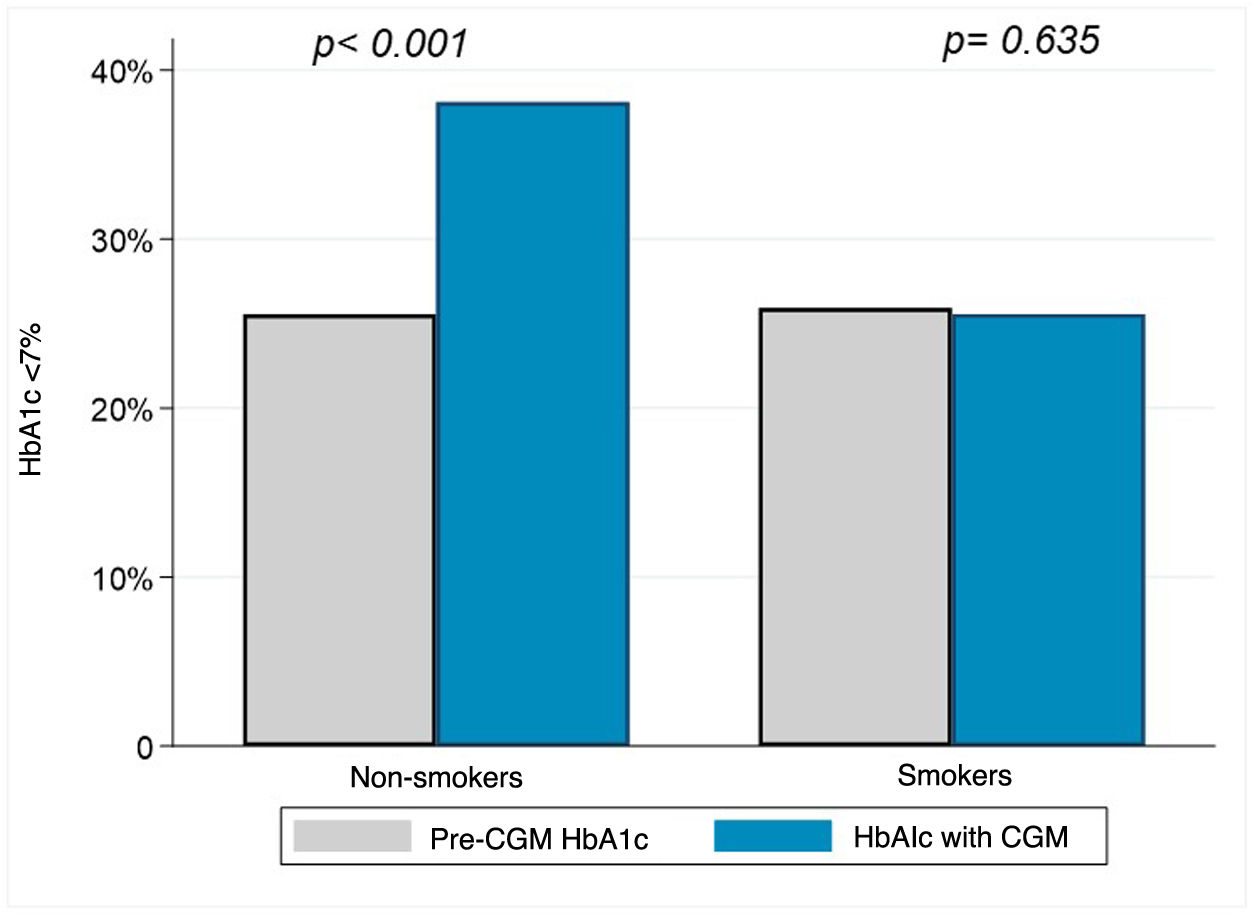

HbA1c target <7% in smokers and non-smokersBefore CGM device placement the proportion of individuals with a HbA1c target (<7%) was 25.9% in smokers and 25.6% in non-smokers; 95% CI 95% [−0.09 to 0.09]. After sensor placement, 38.1% of non-smokers had HbA1c < 7%, while smokers remained at 25.6%; 95% CI 95% [−0.21 to −0.03]. The change in proportion of subjects within HbA1c < 7% in non-smokers was relevant (from 25.6% to 38.1%; 95% CI [0.14−0.36]), with no difference observed in smokers (25.9% pre-sensor and 25.6% post-sensor; 95% CI [95% [−0.13 to 0.21]). Fig. 3 shows the differences in achieving the HbA1c target in smokers and non-smokers.

Additionally a conditional logistic regression model was performed for matched data showing that smoking was associated with not achieving optimal HbA1c ≥ 7%, odds ratio (OR) 1.89, CI 95% [1.13–3.17], in a model adjusted for daily sensor readings OR = 0.93, CI 95% [0.89−0.98], and time as a sensor user, CI 95% [0.75–1.13].

DiscussionThis propensity score-matched cohort study investigated the impact of smoking on HbA1c levels in people with DM1 using a CGM device. The results demonstrated that smoking is an independent factor hindering the improvement in blood glucose control offered by the CGM systems.

The usefulness of glucose monitoring systems in the management of DM is now undisputed.5,16–18 A reduction of up to 0.6% in HbA1c has been reported in patients on multiple doses of insulin in randomised clinical trials compared to those using capillary blood glucose.3,4 The improvement of hypoglycaemia, which is a major concern for people with DM1,19 based on the alarms provided by these devices, is another major advantage of the CGM systems.20 However, despite the evidence supporting the beneficial effect of CGM on chronic DM control, aspects such as the impact of smoking have been little explored. In this sense, randomised clinical trials that have studied the impact of CGM on HbA1c did not include smoking in the analysis3,4 or only had a small sample of smokers,21 much lower than real-world cohort figures, where it is around 20–25% of the population with DM1.22,23

Our work specifically addresses the impact of smoking on HbA1c and shows that smoking hinders HbA1c improvement and the achievement of glycaemic targets in a group of patients matched on the basis of their baseline clinical and socioeconomic characteristics. Our data show that the 0.7% decrease in HbA1c in the non-smoking group after a median of 2.2 years is clinically significant and similar to other studies.3 In contrast, the smoking group showed no significant improvement: 7.9 (1.3%) pre-sensor and 7.7 (1.3%) with the sensor. In addition, the proportion of patients with HbA1c < 7% increased from 25% to 38.1% in non-smokers, while smokers did not show a similar improvement. The multivariate model, adjusted for daily sensor readings7 and time of device use, indicated that smoking independently decreases the likelihood of achieving target HbA1c in CGM users.

These results are consistent with other studies that associate smoking with poorer chronic control of DM124,25 and also in users of CGM devices.26 The mechanisms by which smoking may impair blood glucose control and have an effect on people with DM1 are diverse.

Tobacco use has important effects on hormone secretion. In cell culture, nicotine has been shown to induce insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells by activating mTOR,8 which promotes the development of type 2 diabetes (DM2). Smoking worsens blood glucose control in people already diagnosed with DM2 and also in DM1.26 In addition, smoking induces abnormal secretion of pituitary and counter-regulatory hormones in people with diabetes,27 which may contribute to the multi-causal mechanisms that cause increased hyperglycaemia in people with DM1 who smoke. Targher et al.28 demonstrated that total glucose disposal was significantly reduced in smoking subjects, leading to the conclusion that cigarette smoking aggravates insulin resistance in people with DM2. Although insulin resistance is also relevant in DM1,29 daily insulin dose was an adjustment criterion in our study, suggesting that this factor was controlled in both groups. Smoking is also associated with a less healthy lifestyle, such as lower fruit and vegetable consumption and higher alcohol intake,30 which could contribute to poorer blood glucose control in addition to its direct impact on glucose.

This study has several limitations. Despite using a propensity score-matched design with well-balanced propensity scores and follow-up in two geographically distinct centres, its retrospective nature limits the ability to draw causal conclusions, restricting it to hypothesising. Moreover, as our comparisons are not based on random assignment, we have to recognise that the uncertainty is greater than that reflected by the 95% confidence intervals. On the other hand, tobacco consumption was neither quantified nor objectively assessed by indirect methods, such as carboxyhaemoglobin measurement, nor was its fluctuations during follow-up recorded, which could have influenced the results. In addition, further HbA1c measurements over time were not available, making it difficult to extrapolate additional time trends on the impact of smoking on blood glucose control. Key variables for blood glucose control and its relationship with smoking, such as dietary habits, physical activity or mental health history, were not included, limiting the analysis to clinical and socio-economic factors. The possible existence of unmeasured variables that could influence both the likelihood of being a smoker and blood glucose control represents an important limitation. Although the analysis adjusted for key factors such as age, sex, duration of diabetes and comorbidities, the propensity score methodology cannot control for unobserved or unmeasured variables, which could affect the robustness of the results obtained. Finally, patients with DM2 were not included, which could have strengthened the study’s conclusions.

In conclusion, smoking is a variable that adversely affects glycaemic control and may interfere with the benefits of CGM device use. It is advisable to include smokers in randomised clinical trials to avoid bias and to develop population-based strategies to discourage smoking in people with diabetes to maximise the benefits of the available technology.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors have reviewed and approved the data, contributed to the development and approval of the manuscript, and have agreed on the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

- 1

Conception and design of the manuscript: Fernando Sebastián-Valles.

- 2

Data collection: Juan José Raposo López, Maria Sara Tapia Sanchiz, Iñigo Hernando, Jon Garai and Victor Navas Moreno.

- 3

Data analysis: Fernando Sebastián-Valles and Miguel Antonio Sampedro

- 4

Drafting, reviewing and approving the submitted manuscript: José Alfonso Arranz Martín, Mónica Marazuela, Julia Martínez and Fernando Sebastián-Valles.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital de La Princesa, Madrid (study number: 5084-01/2023) approved this study and exempted patients from informed consent. In view of the retrospective nature of the study, all procedures that were performed were part of routine care.

FundingThis work was funded by Proyectos de Investigación en SaludPI19/00584, PI22/01404 and PMP22/00021 (funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III), iTIRONET-P2022/BMD7379 (funded by the Comunidad de Madrid) and co-financed by FEDER funds to MM.

None.