To elucidate the presence, importance, and characteristics of menstrual changes related to stressful circumstances during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain.

Study designAn online survey was administered in Spain to menstruating women aged 15–55 who had not contracted COVID-19. It collected information on activities during the lockdown, sexual activity, perceptions of emotional status, any changes in menstrual characteristics, and impact on quality of life. The analysis of menstrual changes was limited to responders who did not use hormonal contraception.

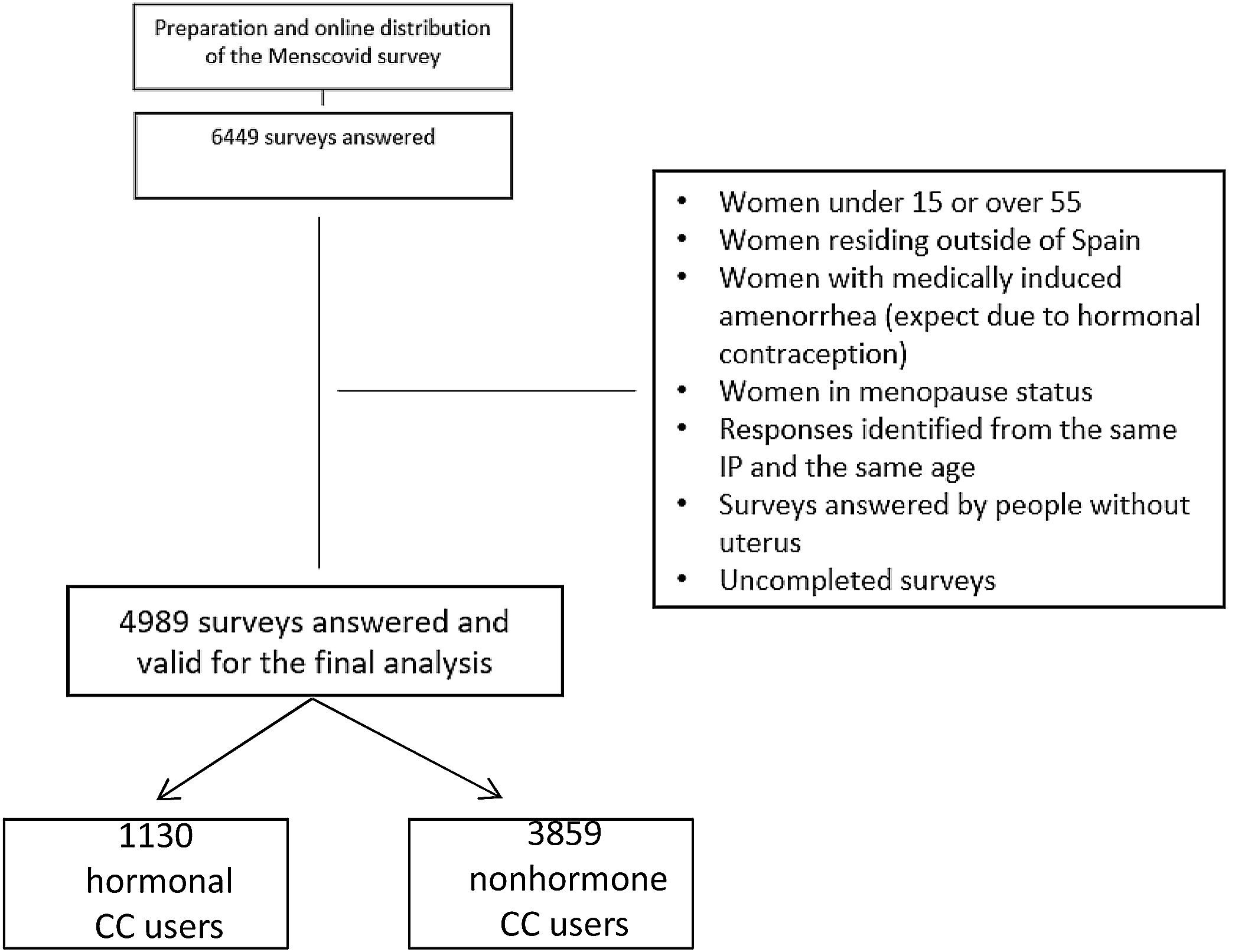

ResultsA total of 6449 women answered the survey, and 4989 surveys were valid for the final analysis. 92.3% of women had at least one menstruation period during the lockdown, while 7.7% had amenorrhea. Quality of life (QoL) associated with menstruation worsened in 19% of women, did not change in 71.7%, and improved in 1.6%. For 50.1% of the women, global QoL worsened during the lockdown; 41.3% remained about the same and 8.7% reported improvement. Sexual activity during the lockdown decreased in 49.8% of the respondents, remained unchanged in 40.7%, and increased in 9.5%. As far the menstrual changes are concerned, there were no statistically significant differences in amenorrhea incidence, regularity of the menstrual cycle, or the amount or duration of menstrual bleeding in non-hormonal contraceptive users when evaluated by the length and characteristics of isolation, the perception of exposure to COVID-19 and the economic or employment situation. Conversely, we found statistically significant differences according to the intensity of changes in emotional status due to lockdown stressors and changes in regularity, duration, and heaviness of menstruation.

ConclusionChanges in emotional status, but not the length and intensity of the isolation or exposure to the disease, significantly influenced menstrual disturbances during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Elucidar la presencia, importancia y características de los cambios menstruales relacionados con estrés durante el confinamiento por COVID-19 en España.

Diseño del estudioEncuesta en línea en España a mujeres de 15 a 55 años que no habían contraído COVID-19. La encuesta recopiló información sobre actividad laboral, actividad sexual, percepciones del estado emocional, características menstruales e impacto en la calidad de vida (CdV).

ResultadosSe recibieron 6.449 encuestas, y 4.989 fueron válidas para el análisis final. El 92,3% tuvieron al menos una menstruación durante el confinamiento, mientras que el 7,7% presentó amenorrea. La QdV asociada con la menstruación empeoró en el 19% de las mujeres, no cambió en el 71,7% y mejoró en el 1,6%. Para el 50,1% de las mujeres, la calidad de vida global empeoró durante el confinamiento; en el 41,3% permaneció igual y el 8,7% mejoró. La actividad sexual disminuyó en el 49,8% de las participantes, se mantuvo igual en el 40,7% y aumentó en el 9,5%. En las no usuarias de anticoncepción hormonal, no hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la incidencia de amenorrea, regularidad del ciclo menstrual o la cantidad y duración del sangrado menstrual relacionadas con la duración y características del aislamiento, la percepción de exposición a la COVID-19 y la situación económica o laboral. Encontramos diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la regularidad, duración y cantidad de la menstruación relacionados con la intensidad de los cambios en el estado emocional por factores estresantes del confinamiento.

ConclusiónLos cambios en el estado emocional, pero no la duración e intensidad del aislamiento o la exposición a la enfermedad, influyeron significativamente en los trastornos menstruales durante el confinamiento por COVID-19.

In the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments had to take emergency measures to prevent the rapid spread of the disease. As in many other countries, the Spanish government chose isolation as an initial measure to mitigate the spread of the disease. Consequently, a significant percentage of the population remained locked down to different degrees from March 14 to May 2, 2020.

For most women, remaining at home added inconveniences such as having to take care of children 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, managing household responsibilities, sharing a reduced space with the whole family, living with partners 24 hours a day, and having to fit in work online.1 Simultaneously, a lesser proportion of society was involved in so-called “essential” activities: most significantly, health care provision but also public transportation, pharmaceutical dispensing, access to food and essential health items in supermarkets, etc. For this subset, exposure to the public involved a higher risk of contagion. This risk added the fear of bringing the disease into the family environment and contaminating their loved ones to work overload, and some chose to forego contact with their families. The overload was especially relevant among healthcare providers caring for people with COVID-19. This group included doctors, nurses, cleaning and transportation personnel at the hospital or primary medicine facility, and caregivers in nursing homes.2,3 In addition, for many people, the lockdown process involved temporary or permanent loss of employment or a significant income decrease.

All these circumstances constitute relevant stressors that negatively impact the psychological well-being of the confined population.4–6

Isolation is associated with stress, anxiety, and depression, and there is experimental and clinical evidence of a higher impact on females.7,8 Clinical gynecologists informally reported subjective perceptions of increased consultations on menstrual disturbances during the lockdown.9–11

To elucidate the existence of these changes and their importance and characteristics, we designed an online survey for menstruating women experiencing different situations during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain.

Materials and methodsThis was a cross-sectional study conducted during the lockdown period in Spain, from March 14 to May 2, 2020. We informed respondents that they gave consent to participate by answering the survey and that they could discontinue their participation by not completing the questionnaire. No trace remained unless they saved the responses to all questions. There were no incentives for participants.

The questionnaireWe designed a survey using the Survey Monkey platform and following the CHERRIES criteria12,13 fulfilling the check list suggestions in the situations when it is appropriate. The authors (JC, JP-C, IG-S, IL, JN), experts on menstrual health, developed a draft of the questionnaire, which was disseminated to 14 women's healthcare providers from different regions in Spain (the members of the Menscovid Group) also experts in menstrual health, to introduce improvements until agreement on a final version was reached. We also submitted the questionnaire to 10 potential respondents not related to health provision environment to check for linguistic adequacy and understanding.

The final questionnaire included 22 items addressing sociodemographic characteristics, social and labor activities (questions 1–8), psychological well-being and sexual activity (questions 9–11), contraceptive use (question 12), and menstrual changes and impact on quality of life (questions 13–22) during the COVID-19 lockdown. Depending on the characteristics of the respondents, they had to answer 12–22 questions. We estimated that answering the whole survey would take less than five minutes. Some questions were multiple choice, and some questions had answers using a visual analog scale (VAS) or a Likert scale. The Spanish version of the questionnaire is accessible at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/MENSCOVID. Readers can find an English version of the questionnaire in the supplementary material.

Women's perception of exposure to COVID-19 during the confinement was measured using a VAS (0.0–100mm: 0=no exposure, 100=worst possible). In order to interpret better the results, regularity, menstrual duration, and menstrual blood loss were assessed with a dichotomic variable: as “usual” or “changed”. Emotional distress perception during the lockdown was evaluated in four situations: activity restriction, the risk of getting the disease, the risk of infecting loved ones and the economic or workplace issues. A 5-item Likert scale was used in each situation (no change to needed medical-psychiatric support). QoL was evaluated in two questions according to the changes in the menstrual pattern and to the impact of the lockdown, with three possible answers: it worsted, it was the same and it improved.

ParticipantsThe target population meeting inclusion criteria was menstruating women from 15 to 55 years old residing in Spain during the lockdown. Having COVID-19 at any time was an exclusionary criterion. A final group of 14 gynecologists from different regions in Spain, who were coauthors of the paper and members of the Menscovid Group, distributed the questionnaire to their mailing lists and social network contacts beginning July 15, 2020. They were asked to disseminate it through friends, coworkers, family members, and social network contacts to obtain a “snowball effect”.

Statistical analysisWe saved all surveys received from July 16 to August 31, 2020. We excluded incomplete surveys from the analysis and considered them only to calculate a ratio of visitors (who completed the first part) to respondents (who completed the entire survey). We prevented duplicate surveys from the same person by restricting access to a single response per IP address.

We also excluded answers from foreign countries and surveys from individuals who did not meet the inclusion criteria: menstruating persons aged 15–55, with an IP address based in Spain.

The questionnaire included a specific question about amenorrhea and its potential causes, enabling the exclusion of responses from participants who were previously amenorrheic.

To avoid the confounding bias of hormonal contraception on menstrual cycle control, we differentiated between women who used any hormonal contraceptive (1130) and those who did not (3859), and we analyzed the changes in the characteristics of the menstrual cycle associated with stress only among the nonusers. We imported the data into Excel and analyzed them using SPSS Statistical Package for Social Sciences.

Absolute and relative frequencies described categorical variables. We used the mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum to describe continuous variables. We used Student's and chi-square tests to compare quantitative and qualitative variables. We verified, in all cases, the appropriateness of conditions for applying the statistical tests employed.

For the descriptive analysis, in categorical variables, we present the number of cases (absolute frequency) along with the percentage (relative frequency). Quantitative variables are described by providing the mean value and standard deviation. In the case of quality of life, given the repeated measurements over time, its frequency distribution has been thoroughly examined, revealing highly symmetrical distributions. This symmetry has enabled the application of repeated measures analysis of variance.

The significance level was set at p<0.05.

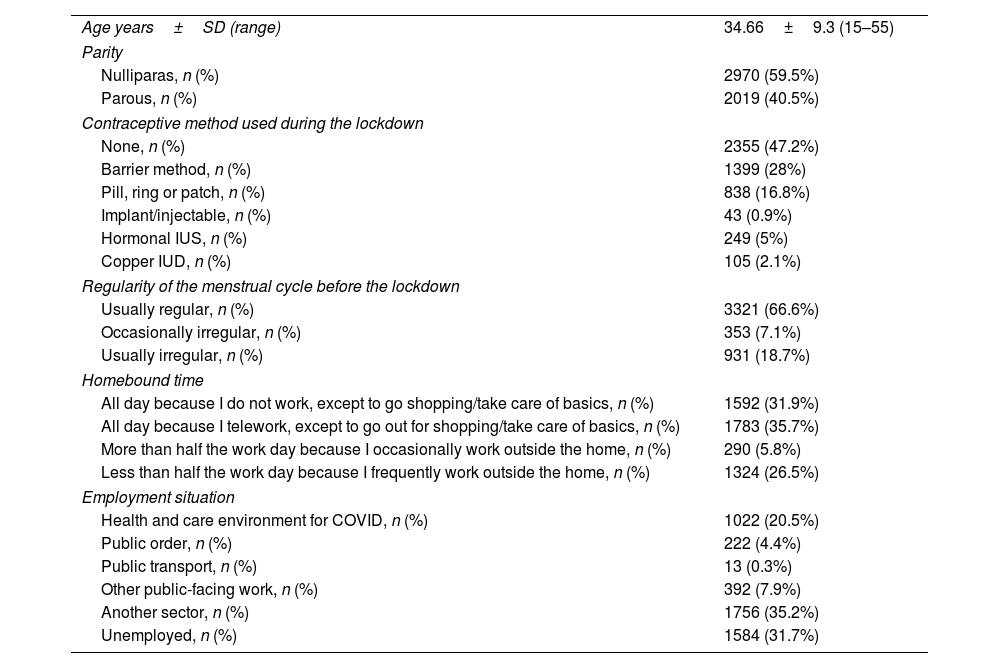

ResultsWe received a total of 6449 responses to the survey, and 4989 surveys were valid for the final analysis (Fig. 1). The mean age of the participants was 34.66±9.3. 47.2% of the women reported not using any contraceptive method, and 66.6% had regular periods. Regarding the time of confinement, 67.6% reported being confined at home throughout the day, and 20.5% worked in health and care environments for COVID-19. In Table 1, we describe the sociodemographic characteristics of all women who completed the survey.

Sociodemographic characteristics of all women (n=4989).

| Age years±SD (range) | 34.66±9.3 (15–55) |

| Parity | |

| Nulliparas, n (%) | 2970 (59.5%) |

| Parous, n (%) | 2019 (40.5%) |

| Contraceptive method used during the lockdown | |

| None, n (%) | 2355 (47.2%) |

| Barrier method, n (%) | 1399 (28%) |

| Pill, ring or patch, n (%) | 838 (16.8%) |

| Implant/injectable, n (%) | 43 (0.9%) |

| Hormonal IUS, n (%) | 249 (5%) |

| Copper IUD, n (%) | 105 (2.1%) |

| Regularity of the menstrual cycle before the lockdown | |

| Usually regular, n (%) | 3321 (66.6%) |

| Occasionally irregular, n (%) | 353 (7.1%) |

| Usually irregular, n (%) | 931 (18.7%) |

| Homebound time | |

| All day because I do not work, except to go shopping/take care of basics, n (%) | 1592 (31.9%) |

| All day because I telework, except to go out for shopping/take care of basics, n (%) | 1783 (35.7%) |

| More than half the work day because I occasionally work outside the home, n (%) | 290 (5.8%) |

| Less than half the work day because I frequently work outside the home, n (%) | 1324 (26.5%) |

| Employment situation | |

| Health and care environment for COVID, n (%) | 1022 (20.5%) |

| Public order, n (%) | 222 (4.4%) |

| Public transport, n (%) | 13 (0.3%) |

| Other public-facing work, n (%) | 392 (7.9%) |

| Another sector, n (%) | 1756 (35.2%) |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 1584 (31.7%) |

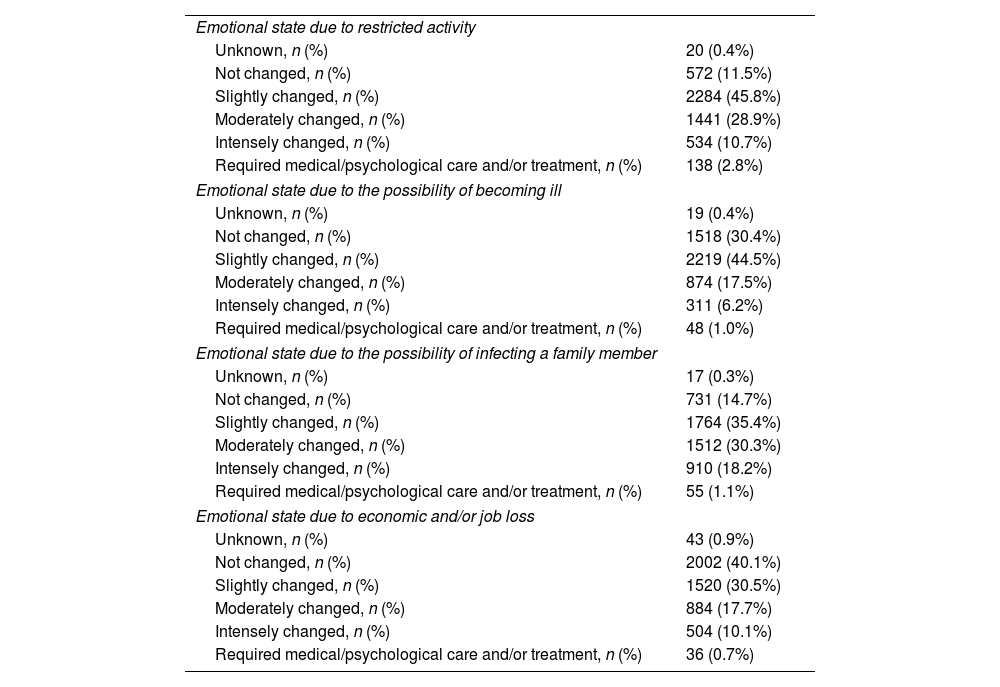

Emotional state intensely changed or required medical/psychological care and/or treatment in 13.5%, 7.2%, 19.3%, and 10.8% of women during the lockdown due to restricted activity, due to the possibility of becoming ill, due to the possibility of infecting a family member and due to economic and/or job loss, respectively (Table 2). The mean perception of exposure to COVID-19 while locked down was 41.55±36.14, and the median was 36 (0–100).

Changes of the emotional state of all women during the lockdown (n=4989).

| Emotional state due to restricted activity | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 20 (0.4%) |

| Not changed, n (%) | 572 (11.5%) |

| Slightly changed, n (%) | 2284 (45.8%) |

| Moderately changed, n (%) | 1441 (28.9%) |

| Intensely changed, n (%) | 534 (10.7%) |

| Required medical/psychological care and/or treatment, n (%) | 138 (2.8%) |

| Emotional state due to the possibility of becoming ill | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 19 (0.4%) |

| Not changed, n (%) | 1518 (30.4%) |

| Slightly changed, n (%) | 2219 (44.5%) |

| Moderately changed, n (%) | 874 (17.5%) |

| Intensely changed, n (%) | 311 (6.2%) |

| Required medical/psychological care and/or treatment, n (%) | 48 (1.0%) |

| Emotional state due to the possibility of infecting a family member | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 17 (0.3%) |

| Not changed, n (%) | 731 (14.7%) |

| Slightly changed, n (%) | 1764 (35.4%) |

| Moderately changed, n (%) | 1512 (30.3%) |

| Intensely changed, n (%) | 910 (18.2%) |

| Required medical/psychological care and/or treatment, n (%) | 55 (1.1%) |

| Emotional state due to economic and/or job loss | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 43 (0.9%) |

| Not changed, n (%) | 2002 (40.1%) |

| Slightly changed, n (%) | 1520 (30.5%) |

| Moderately changed, n (%) | 884 (17.7%) |

| Intensely changed, n (%) | 504 (10.1%) |

| Required medical/psychological care and/or treatment, n (%) | 36 (0.7%) |

During the lockdown, 4605 (92.3%) women reported having at least one menstrual period, while 384 (7.7%) remained amenorrheic. Quality of life (QoL) associated with menstruation worsened in 950 women (19%), did not change in 3575 (71.7%), and improved in 80 (1.6%); 384 (7.7%) women did not answer this question. For 2497 (50.1%) women, global QoL during the lockdown worsened; 2060 (41.3%) remained about the same and 432 (8.7%) reported improvement. Sexual activity during lockdown decreased among 2486 (49.8%) women, remained similar in 2029 (40.7%), and increased in 474 (9.5%).

Among the 3859 women who did not use hormonal contraception, 204 (5.3%) presented amenorrhea during the lockdown. There were no statistically significant differences in the amenorrhea rates according to the time of confinement (p=0.337), the perception of exposure to COVID-19 (p=0.899), employment status (p=0.586), or emotional state (i.e., fear of infecting a family member) (p=0.349) or economic/job loss (p=0.232). Conversely, we found differences in amenorrhea rates among non-hormonal contraception users according to their emotional state during the lockdown due to restricted activity (p<0.01) and the possibility of becoming ill (p=0.011). The higher the emotional stress associated with the lockdown and the perception of risk of exposure to COVID-19, the higher the amenorrhea rates.

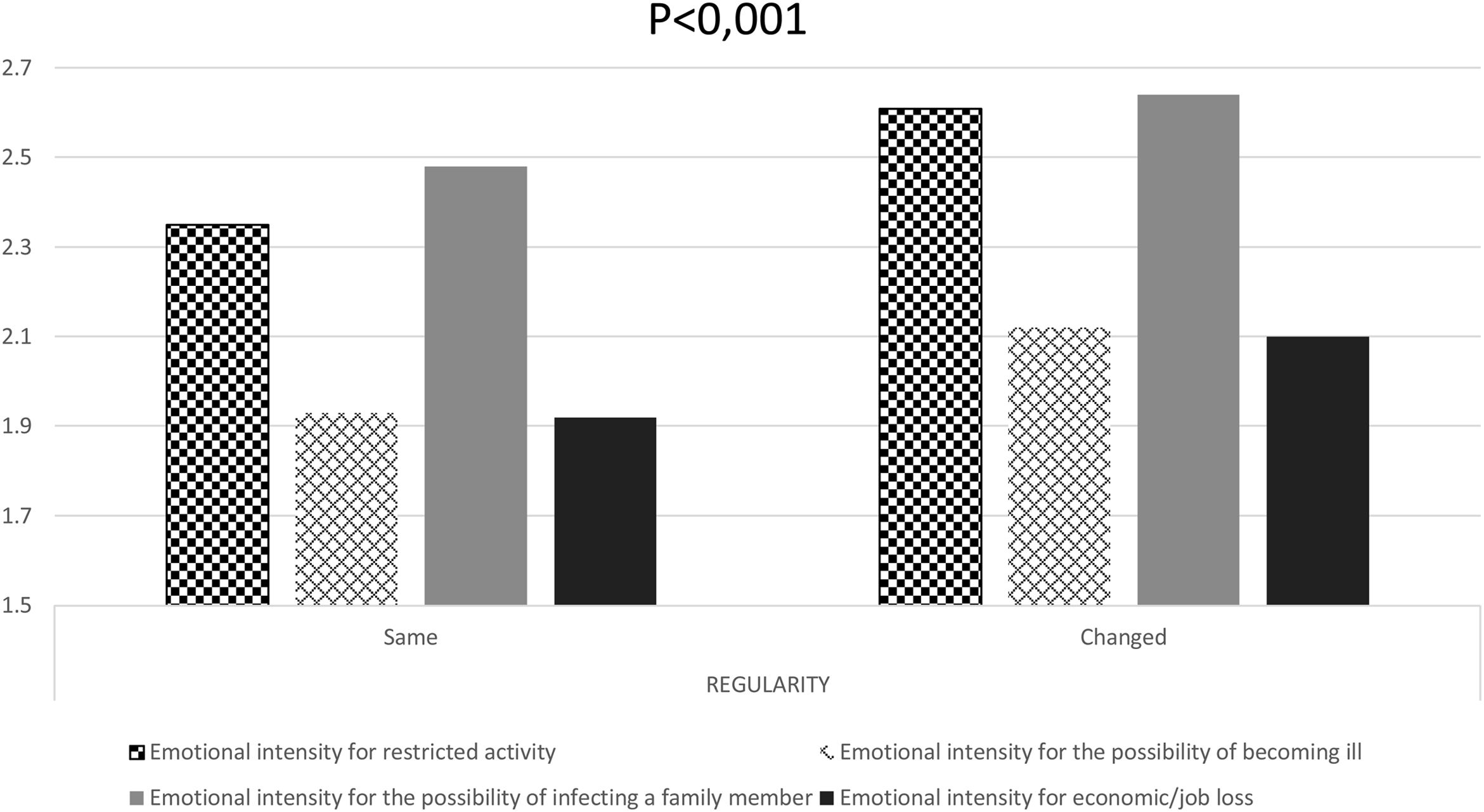

There were no differences in the regularity of menstrual cycles related to the length of the confinement (p=0.147), the perception of exposure to COVID-19 (p=0.966), or the employment situation (p=0.499). However, we found differences related to emotional state on days of the lockdown due to restricted activity (p<0.01), the possibility of infecting a family member (p<0.001), the chance of becoming ill (p<0.001), and economic and job loss (p<0.001) (Fig. 2).

Importance of emotional distress perception in non-hormonal contraceptive users during lockdown due to emotional state related to restricted activity (square boxes), the possibility of becoming ill (grid boxes), the possibility of infecting a family member (solid gray), and economic/job loss (solid black) (n=3655). Chi-square test, p<0.001 in all groups between those where regularity of the cycle remained the same or changed.

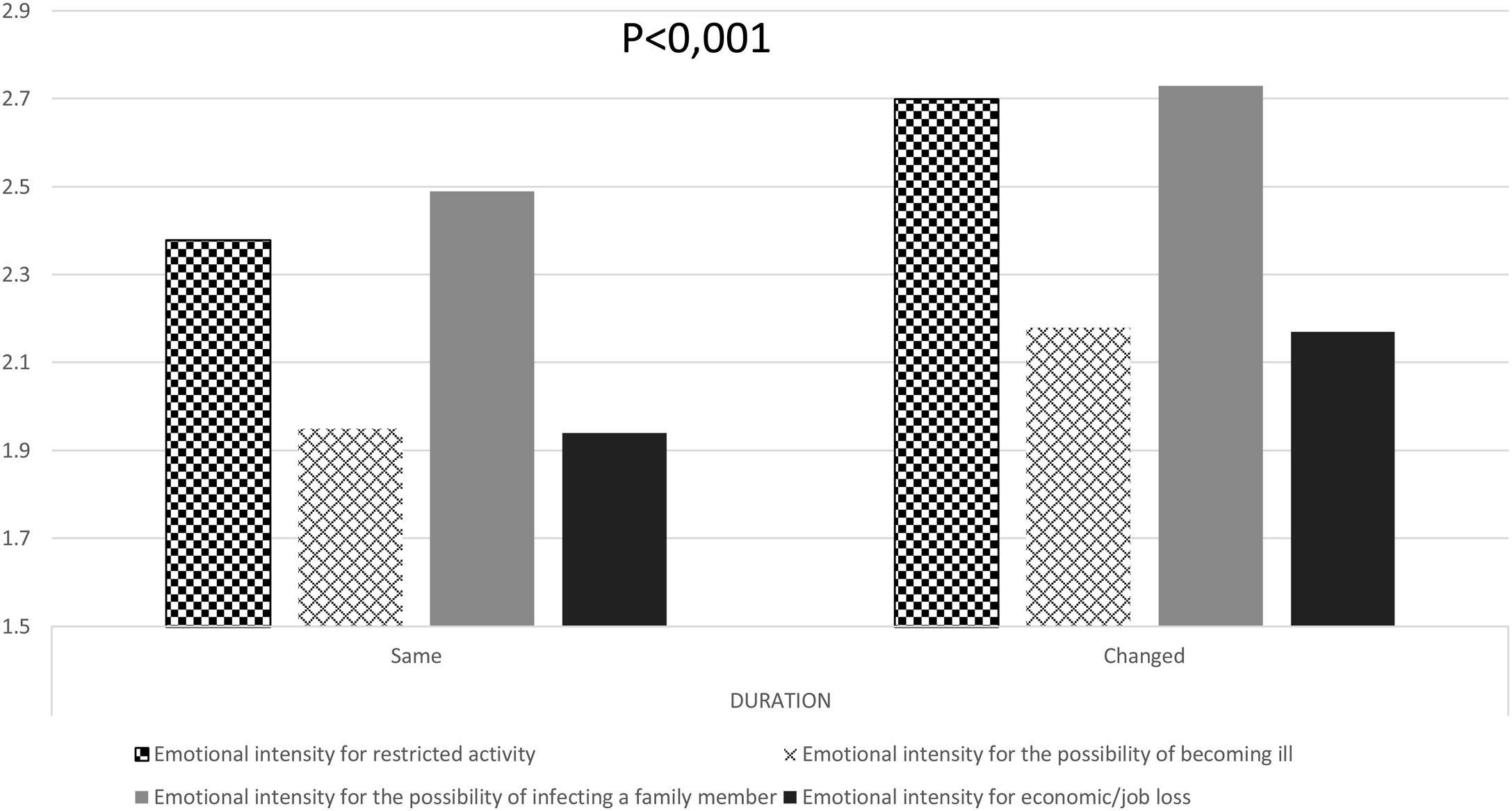

Regarding the duration of menstrual bleeding, there were no statistically significant differences in the percentage of women who reported changes based on their employment situation (p=0.415). We found differences according to their emotional state due to restricted activity (p<0.01), the possibility of infecting a family member (p<0.001), the chance of becoming ill (p<0.001), and economic and job loss (p<0.001) (Fig. 3). We also found differences according to the time of confinement (p=0.02) and the perception of exposure to COVID-19 (p=0.034).

Importance of emotional distress perception in non-hormonal contraceptive users during lockdown due to emotional state related to restricted activity (square boxes), the possibility of becoming ill (grid boxes), the possibility of infecting a family member (solid gray), and economic/job loss (solid black) (n=3655). Chi-square test, p<0.001 in all groups between those where duration of menstruation remained the same or changed.

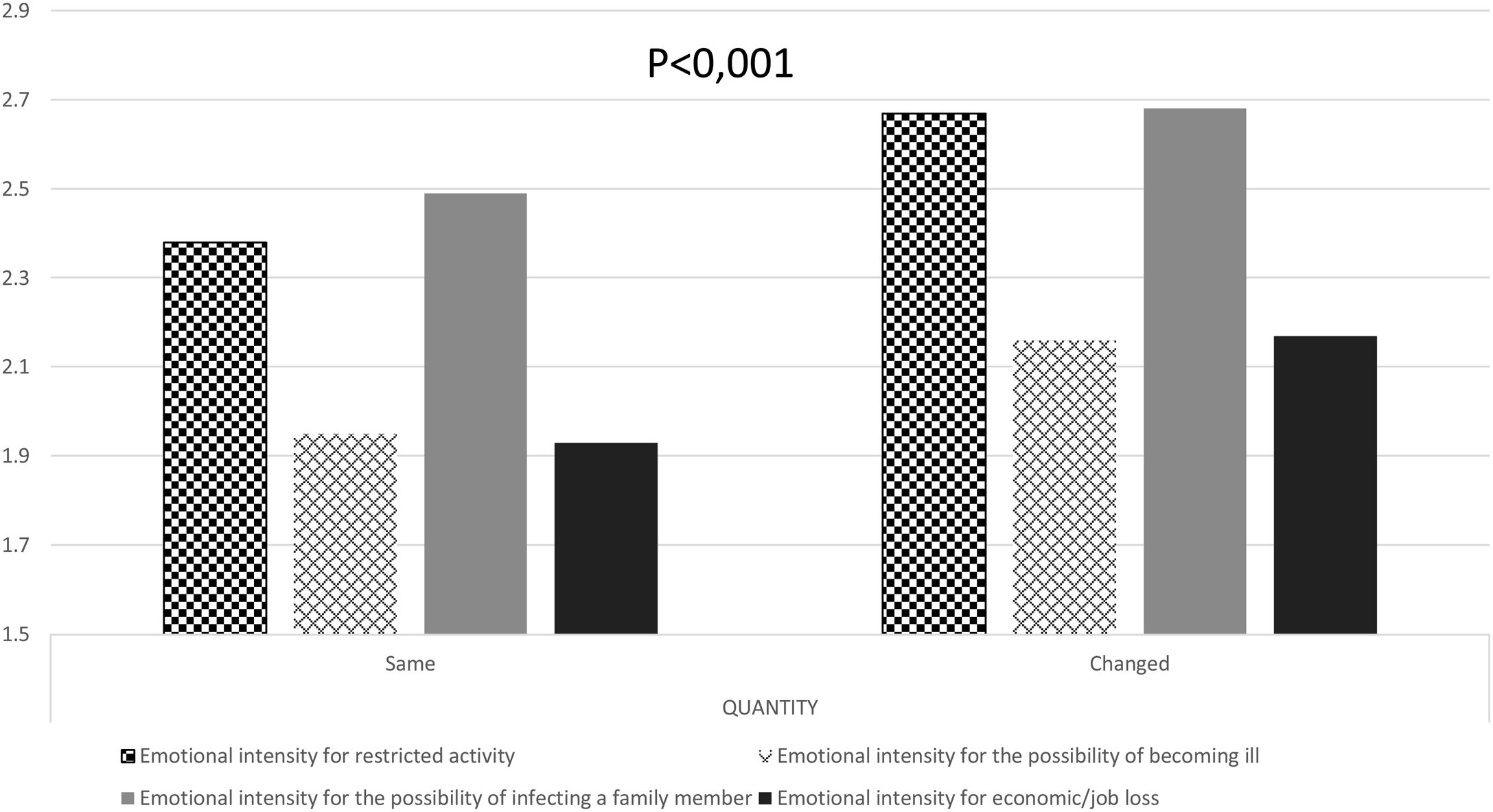

There were no statistically significant differences in the heaviness of menstrual bleeding and the perception of exposure to COVID-19 (p=0.207) or the employment situation (p=0.389). However, we found differences related to the emotional state on days of the lockdown due to restricted activity (p<0.01), the possibility of infecting a family member (p<0.001), the chance of becoming ill (p<0.001), and economic and job loss (p<0.001) (Fig. 4). We also found differences according to emotional changes related to the time of confinement (p=0.041).

Importance of emotional distress perception in non-hormonal contraceptive users during lockdown due to emotional state related to restricted activity (square boxes), the possibility of becoming ill (grid boxes), the possibility of infecting a family member (solid gray), and economic/job loss (solid black) (n=3655). Chi-square test, p<0.001 in all groups between those where heaviness of menstruation remained the same or changed.

We surveyed menstruating women in Spain to identify the menstrual disturbances that may have been affected by COVID-19 lockdown measures and potential contact with the disease. We gathered the most extensive sample of menstruating women published (6449 participants, 4989 eligible for analysis). We excluded from the analysis of menstrual changes women who used hormonal contraception users, had medically induced amenorrhea, or were in menopause. Participants reported changes in the incidence of amenorrhea, cycle length, menstrual duration, and blood loss. From our results, the most significant predictor of a change in the menstrual pattern was the individual perception of anxiety, irrespective of working status, degree of isolation, or vulnerability to the disease. This outcome confirms the hypothesis that menstrual disturbances are the consequence of a stressor on the emotional state and not the severity of the stressor condition. Thus, not all women react identically in front of similar circumstances. These results align with those already published using different tools to evaluate the impact of various aspects of the pandemic lockdown on menstruation.

Two studies14,15 used data from “menstrual trackers”. The results reported are slightly discordant. While Nguyen et al. did not find significant changes in menstrual characteristics when comparing data from the same periods in 2019 and 2020, Haile et al. detected statistically significant, even if clinically irrelevant, changes in menstrual length during the lockdown period. Moreover, Haile et al. sent a prospective survey to study participants and concluded that those reporting stress during the pandemic had significantly longer cycles and longer periods of menstruation than those not reporting stress. When evaluating these studies, it is relevant to underline that the respondents are a specific subset of women. They are well-educated, have regular menstrual cycles, and use the information provided by trackers to prevent or obtain pregnancies. Consequently, their results cannot be extrapolated to the general population.

Phelan et al.16 explored the impact of the pandemic on women's health in a cross-sectional study. Seventy percent of the respondents saved menstrual data with a tracker. While it guarantees the accuracy of the data, it also implies a specific profile for respondents, as previously discussed. Overall, 46% of the responders experienced a change in their menstrual pattern, and 9% reported missed periods. Whereas the medians of the menstrual cycle and length of periods did not change, the variability of these parameters was significantly wider. These changes coexisted with significant increases in psychological changes such as low mood, poor appetite, binge eating, poor concentration, anxiety, or poor sleep. The same research group promoted a second survey to explore, more specifically, the relationship between psychological status and menstrual changes.17 The survey inquired about the changes in menstrual cycle characteristics experienced by participants during the pandemic. Most respondents (77%) recorded menstrual data through an app. The survey also contained 55 questions and four validated questionnaires to evaluate the effect of the pandemic on the incidence and relevance of depression, anxiety, and sleep quality. The analysis of the correlation between psychological impact and menstrual disturbances resulted in a significant positive correlation between both variables.

A self-report survey18 collected information from 210 participants, 54% of whom reported changes in their menstrual patterns. There was a significant positive correlation between these changes and high scores in perceived stress scales.

A very small study with 125 participants evaluated, with validated scales, the relationship between COVID-induced fear and menstrual changes.19 Findings indicated a strong positive correlation between an increase in the women's fear of COVID-19 and the Menstrual Symptom Scale total score.

Additionally, an online questionnaire reporting results from female healthcare providers in Turkey20 found a significantly high incidence of menstrual irregularities among women reporting depression, anxiety, or stress.

A meta-analysis explored the influence of stressors related to the lockdown specifically on menstrual cycle length by comparing data from before and during the lockdown. After pooling all included studies in the final analysis, the OR was 9.1 (CI: 3.16–26.5) in favor of the hypothesis of an effect of lockdown on cycle length.21

Overall, the published evidence confirms the relationship between psychological impact and menstrual changes beyond the quantitative relevance of the environmental changes related to lockdown and fear of exposure to the disease.

Our study has some limitations:

We utilized a non-validated questionnaire due to the necessity of reaching respondents shortly after the lockdown to mitigate potential “recall bias.” The unique circumstances of the situation made it impractical to conduct a validation process. Nonetheless, during the construction of the questionnaire, we took into account the “CHERRIES criteria” to ensure that we could adhere to them when analyzing the responses.

In the “cleaning” process, approximately 22% of the responses were excluded. This exclusion was a result of the pyramidal distribution of the questionnaire, with numerous responses originating from Spanish-speaking countries and transmitted by relatives living in Spain. Additionally, menstruating adolescents or perimenopausal women, who considered themselves eligible to respond, were excluded to prevent other causes of menstrual changes, as specified in the “inclusion criteria.”

Given the size of the final “clean” sample, this exclusion cannot be considered a limitation.

The design of the study does not enable a more specific statistical analysis, but this is compensated by contributing real-life data.

We evaluated the degree of psychological impact with straightforward Likert scales and multiple-choice questions. Even if these measures reduce the accuracy of the evaluation, they make the survey easier to answer and widen the sample. Recruitment was based on social network diffusion, which favors selection bias, as women affected by confinement are more prone to fill out the survey. As a transversal study, we cannot establish causality from our data.

The strengths of the study are as follows: the survey explores socioeconomic data, menstrual information, and psychological status in different sections. The approach in different areas minimizes contamination between questions and evaluates the existence of a relationship between different variables. The recruitment was generated through contacts in social networks and consequently covered a broad spectrum of the menstruating population. The proximity between the last menstruation during the lockdown and the survey was a maximum of one month to reduce the “recall bias”.

The size of the sample and the thoroughness in screening the responses enhance the validity of the results.

ConclusionsThis is the first study that precisely explores the relationship between mental status and menstrual changes during the lockdown. The survey results show that menstrual changes related to lockdown and pandemic stressors were low but relevant. There was no significant relationship between the relevance of isolation, workload intensity, or exposure to the disease and menstrual changes. There is a significant relationship between the intensity of psychological impairment and the incidence of menstrual changes.

Authors’ contributionsJoaquim Calaf, contributed with conceptualization and methodology design, writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Josep Perelló-Capó contributed with conceptualization and methodology design, formal statistical analysis and reviewed the drafts and final version.

Iñaki Lete contributed with conceptualization and methodology design and reviewed the final version.

Ignasi Gich-Saladich contributed to establishing the strategy and formal statistical analysis.

Jesús Novalbos built up the survey with “Survey Monkey” and checked for the appropriateness of data.

The “Menscovid” Research Group members reviewed the questionnaire until reaching a final version and tested its linguistic adequacy and understanding.

Ethical approvalThe study is based on a voluntary answered questionnaire. The respondents acknowledged participation by answering. No individualized data were used.

Participants consentWe informed the respondents that they gave consent to participate by answering the survey and that they could discontinue their participation by not completing the questionnaire.

FundingNo funding has been received to perform this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest about the elaboration of the study.

Fernando Rico Villademoros kindly reviewed the manuscript for structure, spelling, and grammar.

Members of the Menscovid Research Group:

Clara Colomé, IVI Illes Balears, Mallorca.

Marta Correa, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife.

Esther de la Viuda, Guadalajara.

Mercedes Herrero, HM Hospitales, Madrid.

Paloma Lobo, Madrid.

Félix Lugo, Barcelona.

Marian Obiol, Centro de Salud Sexual y Reproductiva Fuente de San Luis, Valencia.

Isabel Ramírez, UGC Dr Cayetano Roldán, San Fernando, Cádiz.

Manuel Sánchez Prieto, Instituto Universitario Dexeus, Barcelona.