The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies brings numerous opportunities andchallenges to business innovation. Understanding how firms can leverage AI technologies to create business value, propose responsible solutions to social problems, and achieve sustainable development has become important. Based on the knowledge-based view (KBV), a theoretical model is proposed to examine the impact of AI capability on responsible innovation. The study focuses on the mediating role of boundary-spanning search and the moderating roles of knowledge field activity and tech-for-good culture. Hierarchical regression analysis and bootstrapping are applied to data from 520 Chinese high-tech small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The results indicate that AI capability positively influences responsible innovation. This relationship is fully mediated by boundary-spanning search. Knowledge field activity and tech-for-good culture moderate the relationships between AI capability and boundary-spanning search and between boundary-spanning search and responsibleinnovation. They also moderate the indirect effect of boundary-spanning search on the relationship between AI capability and responsible innovation. This study contributes to the literature on AI capabilities and innovation outcomes. It also provides practical insights for managers of high-tech SMEs and policymakers to foster responsible innovation.

From large language models driving a paradigm shift in natural language processing to deep learning methods enabling autonomous driving and robot perception, and further to novel systems achieving breakthroughs in knowledge mining and intelligent decision-making, artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming the landscape of knowledge production and innovation in human society at an unprecedented pace. It has become the foremost technological priority for organizations worldwide. However, these innovative advancements are accompanied by significant ethical challenges, including algorithmic bias, data privacy risks, and intellectual property disputes (Akter et al., 2023; Rana et al., 2024). In this context, questions about responsibility in AI-driven innovation have become increasingly prominent.

Existing research has firmly established the positive effects of AI in optimizing operational processes and enhancing organizational agility (Peretz-Andersson et al., 2024). However, it should be emphasized that achieving sustainable competitive advantages does not stem from AI technologies alone, but from a firm’s AI capability—that is, its ability to effectively integrate tangible, human, and intangible AI-related resources to unlock the technology’s full potential (Mikalef & Gupta, 2021). Recent studies have further expanded the value dimensions of AI capability, including enhancing innovation efficiency (Abou-Foul et al., 2023) and reducing the environmental impact of innovation activities (Kumar et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025). Nevertheless, little is known about the mechanisms through which AI capability shapes ethical aspects of innovation responsibility, particularly in the context of high-tech small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs; Zhang et al., 2025). Compared to large enterprises, high-tech SMEs often face dual constraints: limited resources and intense innovation pressure (Hervas-Oliver et al., 2021). These challenges may lead them to prioritize short-term technological breakthroughs over ethical considerations, thereby risking misalignment with broader social responsibility goals. To address these research gaps, this paper introduces the concept of responsible innovation (RI)—a conceptual framework that emphasizes the ethical dimensions of innovation. RI requires corporate innovation activities to meet four-dimensional criteria: predictive anticipation, stakeholder inclusiveness, social demand responsiveness, and reflexivity (Stilgoe et al., 2013). This paradigm ensures that innovation outcomes balance technological, social, and environmental values (Von Schomberg, 2011; Owen et al., 2012). Therefore, exploring the impact of AI capability on RI can offer theoretical guidance to high-tech SMEs in addressing ethical dilemmas.

RI is deeply embedded in its context and characterized by dynamic feedback mechanisms (Stilgoe et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2023). This requires enterprises to continuously integrate technical knowledge with social value knowledge, including ethical standards and stakeholder demands. Based on the knowledge-based view (KBV), knowledge is the core strategic resource of an enterprise, and its acquisition, integration, and reconstruction directly influence innovation efficiency (Grant & Baden-Fuller, 2004). Therefore, to implement RI practices, high-tech SMEs must overcome resource constraints through boundary-spanning search—a process of acquiring heterogeneous social and ethical knowledge by engaging diverse stakeholders across organizational and disciplinary boundaries (Zahoor et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2023). In this process, AI capability serves as a powerful knowledge-processing tool that significantly enhances the efficiency of firms’ knowledge management. By optimizing knowledge acquisition with machine learning (Lindley & Wilkins, 2023), enhancing integration through deep learning, and expanding knowledge reconstruction via natural language processing (Arias-Perez & Cepeda-Cardona, 2022; Jarrahi et al., 2023), enterprises can more effectively complete the entire process of knowledge identification, absorption, and application involved in boundary-spanning search. Therefore, boundary-spanning search may be a crucial mediating factor in revealing the mechanism linking AI capability and RI in high-tech SMEs.

Additionally, the situational perspective of the KBV emphasizes that knowledge creation and transfer are inherently context-dependent. This means that enterprises must thoroughly consider environmental complexity when leveraging knowledge for innovation (Grant, 1996; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1996). From the perspective of the external environment, boundary-spanning search involves the flow of knowledge resources between enterprises and their partners, forming a shared knowledge field. Unlike large enterprises with well-established R&D infrastructures and abundant resources, high-tech SMEs tend to rely more heavily on such knowledge field (Audretsch & Lehmann, 2005). Knowledge field activity reflects the willingness of its members to actively exchange and interact, driven by shared values (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1996). Thus, in highly active knowledge fields, the knowledge-processing advantages provided by AI capability are likely to be more fully leveraged, thereby amplifying its positive impact on boundary-spanning search and RI. From the perspective of the internal environment, organizational culture shapes the allocation of knowledge resources by influencing goal orientation in knowledge integration (Alavi et al., 2005; Azeem et al., 2021). High-tech SMEs, characterized by flatter organizational structures, are often more effective at diffusing cultural values throughout the organization. To achieve RI, these firms require a culture that supports technology for good—one that embeds social responsibility and ethical values at its core. This cultural orientation aligns technological development with societal well-being and ensures that innovation adheres to public interests and sustainable development goals (Mao et al., 2020). In organizations where a tech-for-good culture is strongly established, AI capabilities and knowledge acquired through boundary-spanning search are more likely to be directed toward solving societal problems, thereby enhancing RI outcomes.

Based on the analysis above, this study aims to answer the following questions:

RQ1 Does AI capability affect RI in high-tech SMEs?

RQ2 Does boundary-spanning search mediate the relationship between AI capability and RI?

RQ3 How do knowledge field activity and tech-for-good culture moderate the impact of AI capability on RI?

Based on the KBV, this study assesses the direct impact of AI capability on RI, as well as the mediating role of boundary-spanning search in this relationship. Additionally, it examines the internal and external environments in which organizations operate during knowledge acquisition and creation, exploring how knowledge field activity and tech-for-good culture influence the mechanisms connecting AI capability to RI. To empirically test the proposed model, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted using survey data collected from 520 Chinese high-tech SMEs. The main reason for selecting this research subject is that, in recent years, the Chinese government has issued a series of policies emphasizing that AI development requires both technological innovation and ethical governance. As key enablers in the implementation of emerging technologies such as AI, high-tech SMEs play a crucial role in building AI capabilities and practicing RI. These efforts are essential not only for generating commercial value but also for serving as a vital bridge to reconcile technological innovation with social value conflicts. Thus, this study provides localized empirical evidence for AI ethical governance in China and offers a unique Chinese approach for emerging economies to balance technological innovation with social responsibility.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the theoretical background and develops the research hypotheses. Section 3 details the study design, variables, and measurement methods. Section 4 presents the findings. Section 5 discusses the theoretical and managerial implications, acknowledges limitations, and suggests potential directions for future research.

Theory and hypothesesAI capability and responsible innovationEnterprises with advanced AI capabilities can effectively integrate tangible resources, such as data and algorithmic technologies, to support complex model training and large-scale data processing (Zhang et al., 2025). This capability enables high-tech SMEs to better identify market trends, customer needs, and risks (Sullivan & Fosso Wamba, 2024), thereby facilitating more informed and responsible decision-making while fostering innovation. Furthermore, managers in high-tech SMEs with advanced AI capabilities excel at planning and deploying AI technologies while coordinating collaboration between technical teams and frontline staff (e.g., sales and production roles) (Fountaine et al., 2019). This collaboration is essential because frontline employees provide authentic market feedback and user insights (Kiron, 2017), enabling technology teams to develop more practical and socially valuable products that dynamically address societal needs and promote RI.

High-tech SMEs with robust AI capabilities can accelerate organizational transformation by automating traditional manual tasks, fundamentally changing how innovation activities are executed (Al Halbusi et al., 2025; Singh et al., 2024). Consequently, these enterprises can proactively identify potential process inefficiencies, fostering more efficient and sustainable innovation initiatives. Moreover, compared to conservative firms, those with advanced AI capabilities exhibit a stronger willingness to deviate from standard practices and pursue ambitious goals (Mikalef & Gupta, 2021). By doing so, they are better positioned to identify and address the ethical, social, and environmental risks associated with innovation, in turn fostering a more RI paradigm. Based on this reasoning, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1 AI capability positively affects RI.

The KBV posits that knowledge is a critical strategic resource for achieving competitive advantage, with its possession, scarcity, and irreplaceability generating potential value for organizations (Grant, 1996). For high-tech SMEs, boundary-spanning search—the acquisition of external knowledge from diverse fields such as ethics and social science—serves as an essential mechanism for enhancing their knowledge base and achieving innovation goals (Zhu et al., 2023). This activity embodies the collaborative governance principle of RI, highlighting its vital role in successful RI implementation. Furthermore, AI-driven knowledge management systems bolster knowledge sharing both within and across organizations (Al Halbusi et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025), which in turn elevates the efficacy of boundary-spanning searches. Thus, we propose that AI capability fosters RI by enhancing boundary-spanning search.

First, AI capability positively influences boundary-spanning search. On one hand, AI capability breaks down internal information silos, facilitating cross-functional collaboration (Mikalef & Gupta, 2021). This allows firms to process and analyze vast, multi-source datasets, thereby overcoming conventional search constraints and substantially expanding the scope of their boundary-spanning efforts. On the other hand, deploying AI to achieve organizational objectives cultivates sustained learning capabilities (Harfouche et al., 2023). By doing so, it empowers enterprises to utilize machine learning and knowledge graphs to precisely extract relevant knowledge and discern complex interdependencies within extensive data, thereby adding significant depth to complement the breadth of boundary-spanning search.

Second, boundary-spanning search can further promote RI. Specifically, high-tech SMEs constrained by limited resources often encounter challenges in innovation (Zahoor et al., 2024). Boundary-spanning search effectively integrates resources from multiple stakeholders (Fraaije & Flipse, 2020), addressing innovation resource gaps and refining practices through external feedback (Stilgoe et al., 2013). Thus, it facilitates the implementation of RI. Additionally, boundary-spanning search enables high-tech SMEs to accurately identify market demands and social preferences while continuously gathering public feedback on emerging technologies (Xue & Wang, 2024). By doing so, it provides real-time insights necessary to promptly identify associated ethical risks and societal impacts (Xie et al., 2024), fostering dynamic strategy adjustments and ensuring that technological development remains aligned with public values. Based on the above discussion, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2 Boundary-spanning search mediates the relationship between AI capability and RI.

A firm’s external knowledge search is heavily contingent upon its internal environment for knowledge acquisition and processing (Guo & Wang, 2014). Nonaka and Takeuchi (1996) introduced the concept of ba (a knowledge field) to describe this environment—a dynamic, shared space that facilitates knowledge exchange, utilization, transfer, and innovation. Knowledge field activity reflects participants’ commitment to knowledge diffusion, inheritance, and aggregation. When the knowledge field is highly active, high-tech SMEs are more likely to experience a knowledge agglomeration effect, thereby creating a more open environment for knowledge interaction that is marked by widened flow channels and improved efficiency (Wang et al., 2025). Under these conditions, AI-capable enterprises are better positioned to precisely identify, integrate, and leverage external knowledge, thereby substantially enhancing the effectiveness of their boundary-spanning search.

However, in environments with low knowledge field activity, the mobility and interactivity of knowledge are significantly constrained. This limitation consequently erodes mutual trust and fosters a reluctance to share information between high-tech SMEs and external entities (Wang et al., 2025). In such scenarios, even AI-capable firms may lack the motivation to utilize AI for absorbing and integrating new external knowledge, ultimately undermining boundary-spanning search. Moreover, low knowledge field activity impedes knowledge renewal and evolution. This stagnation means that AI systems may process outdated information or lack exposure to forward-looking insights, thereby significantly compromising the effectiveness of boundary-spanning search initiatives.

H3a Knowledge field activity moderates the positive relationship between AI capability and boundary-spanning search. The stronger the knowledge field activity, the stronger this relationship is.

Building on H2 and H3a, this study proposes a moderated mediation model. Specifically, the KBV posits that corporate innovation advantages arise from the integration and combination of heterogeneous knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1996). Building on this theory, a highly active knowledge field fosters an ideal environment for effective communication and mutually beneficial relationships between AI-capable high-tech SMEs and diverse knowledge stakeholders. This dynamic facilitates deeper exploration and utilization of existing knowledge bases, amplifying knowledge aggregation effects and driving RI outcomes. Conversely, insufficient knowledge field activity induces expertise homogenization (Gan & Qi, 2018), which hinders access to diverse knowledge and results in a rigid knowledge dilemma—relying on existing experience and routine processes to solve problems (Liao et al., 2008). Further, this violation of the KBV’s principle of dynamic knowledge base maintenance (Grant, 1996) suppresses innovative inspiration and reduces the efficiency of RI. Based on this reasoning, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3b Knowledge field activity moderates the mediating role of boundary-spanning search between AI capability and RI.

The KBV emphasizes that the effectiveness of knowledge integration depends on guidance from shared values (Nonaka, 1994). A tech-for-good culture reflects an organizational mindset that proactively integrates social responsibility and ethical standards into technological innovation (Li et al., 2021). This ethos, in turn, guides the value orientation and decision-making processes involved in knowledge acquisition and integration. Therefore, this study posits that a strong tech-for-good culture orients boundary-spanning searches toward domains of ethical compliance and social value creation, rather than a narrow focus on technological or commercial objectives. This helps enterprises to prioritize addressing social challenges with external knowledge, thereby amplifying the positive effect of boundary-spanning search on RI. Conversely, without the guidance of a robust tech-for-good culture, high-tech SMEs are prone to a technology-centric mindset. This can lead to the uncritical adoption of external knowledge while overlooking social needs, ultimately resulting in innovations that lack practical value. Based on this, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4a Tech-for-good culture moderates the positive relationship between boundary-spanning search and RI, and the stronger the tech-for-good culture, the stronger this relationship is.

During RI processes, high-tech SMEs often venture into uncharted domains to acquire new knowledge and generate new ideas and strategies (Xie & Wang, 2021). However, this exploratory approach inherently amplifies ethical risks, particularly due to AI’s unpredictability, which may lead to unintended consequences or reinforce existing biases (Singh et al., 2024). From a knowledge governance perspective grounded in the KBV, a tech-for-good culture functions as a potent informal governance mechanism (Foss et al., 2010). It operates by shaping the cognitive frameworks and behavioral norms of organizational members, thereby effectively guiding corporate processes such as knowledge validation (e.g., ethical review) and integration (e.g., embedding ethical guidelines). Therefore, high-tech SMEs with strong tech-for-good cultures can leverage AI to conduct boundary-spanning searches in a more transparent, fair, and responsible manner. This approach can significantly reduce risks like data security issues, ensuring that their innovation activities reconcile technological advancement with social value. Conversely, organizations with underdeveloped tech-for-good cultures risk fostering information fabrication during AI-enabled boundary-spanning searches. Such unethical practices may introduce contaminated knowledge into organizational systems (Alavi et al., 2024), distorting decision-making processes and innovation trajectories. This ultimately results in technically feasible but ethically misaligned solutions that fail to address genuine societal needs, thereby undermining the core objectives of RI. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4b Tech-for-good culture moderates the mediating role of boundary-spanning search between AI capability and RI.

Based on the above discussion, Fig. 1 presents our conceptual model integrating these relationships.

MethodThis study employs hierarchical regression analysis to empirically test the theoretical framework. This methodology introduces predictors sequentially, which identifies linear causal relationships between variables. It further allows for a systematic examination of how moderating variables influence the relationships between the original independent and dependent variables (Cohen et al., 2013). Compared to traditional regression analysis, hierarchical regression not only quantifies the unique explanatory variance (ΔR²) of each predictor but also provides precise estimates of effect size (β coefficient) and statistical significance at each step. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26.0. The General Linear Model (GLM) module was primarily used for hierarchical regression analysis. The bootstrap method was utilized to test both mediation and moderated mediation effects. Additionally, simple slope analysis was conducted to examine the specific pattern of the moderating effect.

Sample and dataThe data for our study were collected from high-tech SMEs located in the Yangtze River Delta region of China. This area is characterized by its economic vitality and innovative ecosystem, making it a leading hub for high-tech SMEs and thus an ideal context for our research. A pilot test was conducted with 30 representative enterprises to refine the survey instrument. Subsequently, during the formal research phase, 1000 high-tech SMEs were randomly selected from a list provided by local governments in the Yangtze River Delta region. After communicating the study’s purpose and guaranteeing anonymity, 628 companies agreed to participate in the survey.

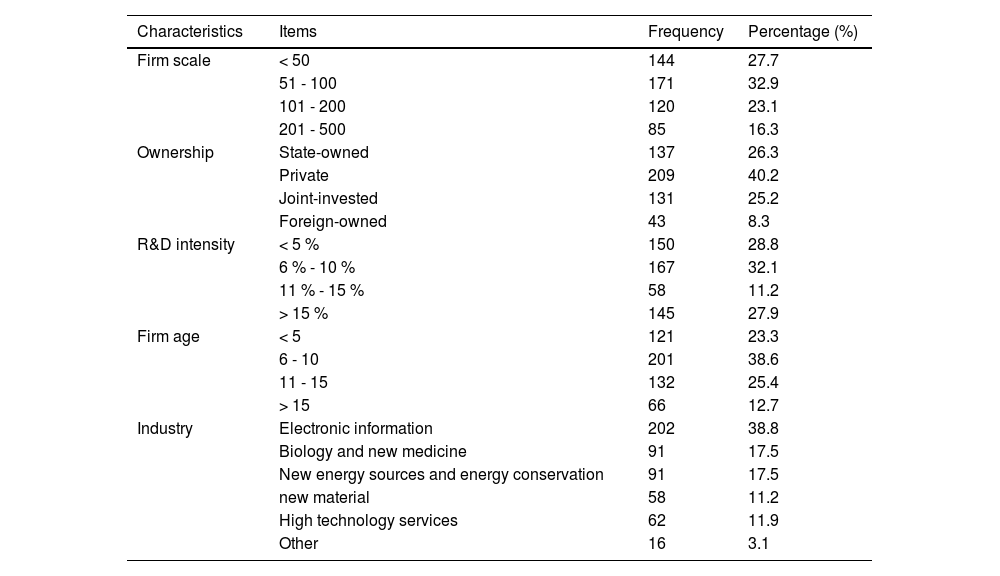

The questionnaire was distributed via the Credamo platform, targeting MBA and EMBA students who serve as middle and senior managers in high-tech SMEs, thus ensuring direct access to qualified informants. To ensure the accuracy and representativeness of the sample, this study implemented rigorous screening criteria during the questionnaire design. First, respondents were required to work at enterprises located in the Yangtze River Delta region. Second, only managers (e.g., CEO, CTO, R&D manager) were qualified as respondents, a criterion enforced by Credamo’s automated screening system. These managers are uniquely qualified as informants due to their intimate familiarity with corporate strategic decision-making and daily operations, enabling them to accurately assess the interactions among the study’s variables, including AI capability, boundary-spanning search, RI, knowledge field activity, and tech-for-good culture. This sampling method effectively ensures the reliability and validity of the research data. Ultimately, 520 complete responses were collected, resulting in a response rate of 52.0 %. The characteristics of the samples are presented in Table 1.

Samples characteristics.

Our study primarily utilizes established scales from existing research. The English scales were translated through back-translation. Measurement employed a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)..

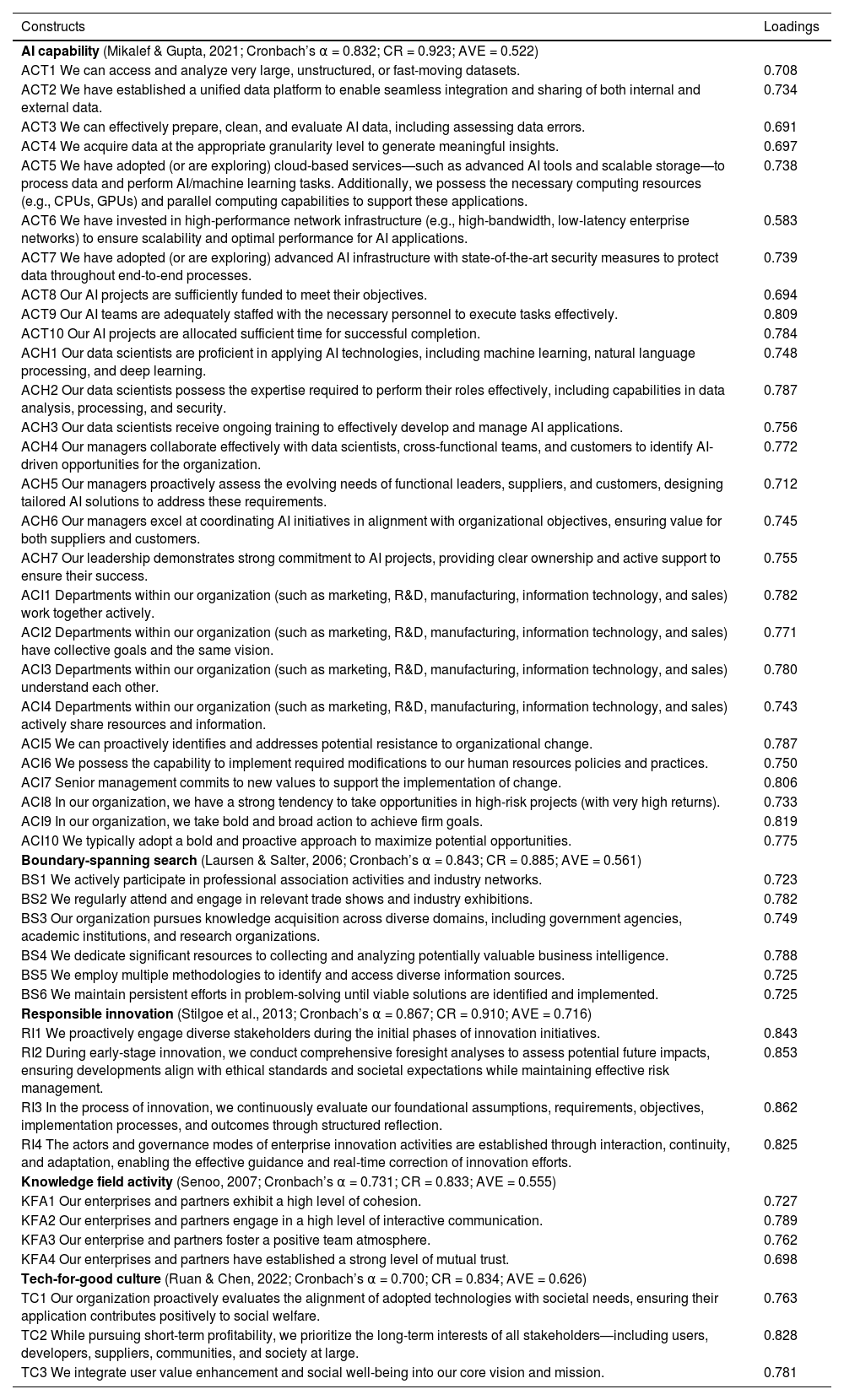

The scale developed by Mikalef and Gupta (2021) was adopted to measure AI capability, which comprises three dimensions: AI capability tangible (ACT), AI capability human skills (ACH), and AI capability intangible (ACI). Considering that an excessive number of original scales may affect respondents’ quality and completion rates, this study retained the core constructs by selecting the most representative items from each dimension, merging items with similar expressions, and refining the language of some items to make them more concise and clear. For instance, this study removed the original statement, “Our AI project execution managers possess strong leadership skills,” because the core concept of leadership capabilities was more thoroughly addressed in a revised formulation: “Our leadership demonstrates strong commitment to AI projects, providing clear ownership and active support to ensure their success.” The revised version not only retains the idea of leadership skills but also emphasizes managerial accountability and ownership. Given its broader scope, the latter formulation is more representative. Finally, this paper uses 10 items to evaluate AI capability tangible, 7 items to assess AI capability human skills, and 10 items to measure AI capability intangible. The results of the preliminary research also demonstrate that the adapted AI capability scale possesses strong reliability and validity. Drawing on the research of Laursen and Salter (2006), boundary-spanning search is measured using six items. Following Stilgoe et al. (2013), this study assesses RI using four key dimensions: anticipation, reflection, responsiveness, and inclusion. Each dimension is measured with a corresponding item. Knowledge field activity is measured based on Senoo’s (2007) framework, utilizing four items. Tech-for-good culture is adapted from Ruan and Chen (2022) and assessed through three items. The specific measurement items are detailed in Table 2.

Measurement items and test results for reliability and validity.

| Constructs | Loadings |

|---|---|

| AI capability (Mikalef & Gupta, 2021; Cronbach’s α = 0.832; CR = 0.923; AVE = 0.522) | |

| ACT1 We can access and analyze very large, unstructured, or fast-moving datasets. | 0.708 |

| ACT2 We have established a unified data platform to enable seamless integration and sharing of both internal and external data. | 0.734 |

| ACT3 We can effectively prepare, clean, and evaluate AI data, including assessing data errors. | 0.691 |

| ACT4 We acquire data at the appropriate granularity level to generate meaningful insights. | 0.697 |

| ACT5 We have adopted (or are exploring) cloud-based services—such as advanced AI tools and scalable storage—to process data and perform AI/machine learning tasks. Additionally, we possess the necessary computing resources (e.g., CPUs, GPUs) and parallel computing capabilities to support these applications. | 0.738 |

| ACT6 We have invested in high-performance network infrastructure (e.g., high-bandwidth, low-latency enterprise networks) to ensure scalability and optimal performance for AI applications. | 0.583 |

| ACT7 We have adopted (or are exploring) advanced AI infrastructure with state-of-the-art security measures to protect data throughout end-to-end processes. | 0.739 |

| ACT8 Our AI projects are sufficiently funded to meet their objectives. | 0.694 |

| ACT9 Our AI teams are adequately staffed with the necessary personnel to execute tasks effectively. | 0.809 |

| ACT10 Our AI projects are allocated sufficient time for successful completion. | 0.784 |

| ACH1 Our data scientists are proficient in applying AI technologies, including machine learning, natural language processing, and deep learning. | 0.748 |

| ACH2 Our data scientists possess the expertise required to perform their roles effectively, including capabilities in data analysis, processing, and security. | 0.787 |

| ACH3 Our data scientists receive ongoing training to effectively develop and manage AI applications. | 0.756 |

| ACH4 Our managers collaborate effectively with data scientists, cross-functional teams, and customers to identify AI-driven opportunities for the organization. | 0.772 |

| ACH5 Our managers proactively assess the evolving needs of functional leaders, suppliers, and customers, designing tailored AI solutions to address these requirements. | 0.712 |

| ACH6 Our managers excel at coordinating AI initiatives in alignment with organizational objectives, ensuring value for both suppliers and customers. | 0.745 |

| ACH7 Our leadership demonstrates strong commitment to AI projects, providing clear ownership and active support to ensure their success. | 0.755 |

| ACI1 Departments within our organization (such as marketing, R&D, manufacturing, information technology, and sales) work together actively. | 0.782 |

| ACI2 Departments within our organization (such as marketing, R&D, manufacturing, information technology, and sales) have collective goals and the same vision. | 0.771 |

| ACI3 Departments within our organization (such as marketing, R&D, manufacturing, information technology, and sales) understand each other. | 0.780 |

| ACI4 Departments within our organization (such as marketing, R&D, manufacturing, information technology, and sales) actively share resources and information. | 0.743 |

| ACI5 We can proactively identifies and addresses potential resistance to organizational change. | 0.787 |

| ACI6 We possess the capability to implement required modifications to our human resources policies and practices. | 0.750 |

| ACI7 Senior management commits to new values to support the implementation of change. | 0.806 |

| ACI8 In our organization, we have a strong tendency to take opportunities in high-risk projects (with very high returns). | 0.733 |

| ACI9 In our organization, we take bold and broad action to achieve firm goals. | 0.819 |

| ACI10 We typically adopt a bold and proactive approach to maximize potential opportunities. | 0.775 |

| Boundary-spanning search (Laursen & Salter, 2006; Cronbach’s α = 0.843; CR = 0.885; AVE = 0.561) | |

| BS1 We actively participate in professional association activities and industry networks. | 0.723 |

| BS2 We regularly attend and engage in relevant trade shows and industry exhibitions. | 0.782 |

| BS3 Our organization pursues knowledge acquisition across diverse domains, including government agencies, academic institutions, and research organizations. | 0.749 |

| BS4 We dedicate significant resources to collecting and analyzing potentially valuable business intelligence. | 0.788 |

| BS5 We employ multiple methodologies to identify and access diverse information sources. | 0.725 |

| BS6 We maintain persistent efforts in problem-solving until viable solutions are identified and implemented. | 0.725 |

| Responsible innovation (Stilgoe et al., 2013; Cronbach’s α = 0.867; CR = 0.910; AVE = 0.716) | |

| RI1 We proactively engage diverse stakeholders during the initial phases of innovation initiatives. | 0.843 |

| RI2 During early-stage innovation, we conduct comprehensive foresight analyses to assess potential future impacts, ensuring developments align with ethical standards and societal expectations while maintaining effective risk management. | 0.853 |

| RI3 In the process of innovation, we continuously evaluate our foundational assumptions, requirements, objectives, implementation processes, and outcomes through structured reflection. | 0.862 |

| RI4 The actors and governance modes of enterprise innovation activities are established through interaction, continuity, and adaptation, enabling the effective guidance and real-time correction of innovation efforts. | 0.825 |

| Knowledge field activity (Senoo, 2007; Cronbach’s α = 0.731; CR = 0.833; AVE = 0.555) | |

| KFA1 Our enterprises and partners exhibit a high level of cohesion. | 0.727 |

| KFA2 Our enterprises and partners engage in a high level of interactive communication. | 0.789 |

| KFA3 Our enterprise and partners foster a positive team atmosphere. | 0.762 |

| KFA4 Our enterprises and partners have established a strong level of mutual trust. | 0.698 |

| Tech-for-good culture (Ruan & Chen, 2022; Cronbach’s α = 0.700; CR = 0.834; AVE = 0.626) | |

| TC1 Our organization proactively evaluates the alignment of adopted technologies with societal needs, ensuring their application contributes positively to social welfare. | 0.763 |

| TC2 While pursuing short-term profitability, we prioritize the long-term interests of all stakeholders—including users, developers, suppliers, communities, and society at large. | 0.828 |

| TC3 We integrate user value enhancement and social well-being into our core vision and mission. | 0.781 |

This study selects firm age, firm size, ownership type, industry type, and R&D intensity as control variables, based primarily on the following considerations: Firm age shapes innovation modes, as younger enterprises exhibit a greater tendency to embrace AI technologies and RI concepts than mature firms (Hussain et al., 2024). Firm size determines its resource endowments. Medium-sized enterprises, unlike their smaller counterparts, typically have the necessary resources to undertake innovation and research initiatives (Halme & Korpela, 2014). Additionally, ownership type influences innovation orientation, with systematic differences in the fulfillment of social responsibilities observed among enterprises with varying ownership structures (Duran et al., 2016). Industry types reflect distinct characteristics of innovation, as high-tech industries face more stringent technical ethics requirements (Zhang et al., 2023). R&D intensity indicates the level of technological innovation, and enterprises with high R&D investment place greater emphasis on technical ethics (Kim et al., 2013). In this study, firm age is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of years since the company’s establishment, while firm size is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of employees. Ownership type is controlled using a dummy variable (1 = state-owned enterprises, 0 = non-state-owned enterprises). To account for industry effects, this study includes dummy variables for five industry types (1= electronic information, 0= other; 2= biology and new medicine, 0= other; 3= new energy sources and energy conservation, 0= other; 4= new materials, 0= other; 5= high technology services, 0= other). R&D intensity is measured as the ratio of annual R&D expenditure to total annual sales over the past three years, ranging from 1 (< 5%) to 5 (> 15%), as per (Xie et al., 2024).

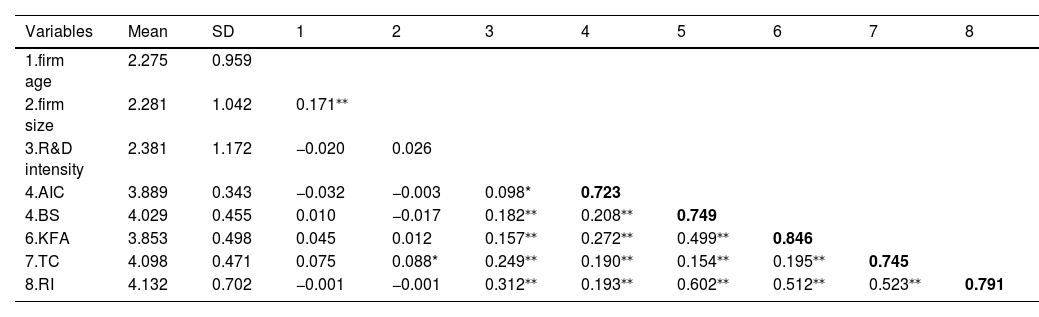

Validity and reliabilityThe reliability, convergent validity, content validity, and discriminant validity of the scale were assessed. In this study, Cronbach’s α, factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated using SPSS 26.0. As shown in Table 2, the Cronbach’s α and CR values for all variables exceeded the threshold of 0.700 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), indicating that the scale demonstrates adequate reliability. The factor loadings were above 0.500, and the AVE was greater than 0.500, suggesting that the scale possesses high convergent validity. Content validity was established through a literature review, interviews with managers, and preliminary research. Finally, the descriptive statistics presented in Table 3 show that the square root of the AVE for each variable is greater than the correlation coefficient between any two variables, further confirming the good discriminant validity of each variable (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Additionally, this study tested for potential multicollinearity by evaluating the variance inflation factor (VIF). All VIF values were below the threshold of 10, indicating that multicollinearity was not a serious concern (Mason and Perreault, 1991).

Mean, standard deviations, and correlations.

Note(s): S.D. = Standard Deviation, AI capability = AIC, Boundary-spanning search = BS, Knowledge field activity = KFA, Tech-for-good culture = TC, Responsible innovation = RI *p < 0.05; ⁎⁎p < 0.01; ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Bold values on the diagonal in the correlation matrix are square roots of AVE (variance shared between the constructs and their respective measures).

The questionnaire survey method is frequently criticized for issues related to non-response bias and common method bias (CMB; Kong et al., 2021). T-tests were employed to compare corporate characteristics between the top 25 and bottom 25 respondents. The results showed no any statistically significant differences (p > 0.05), confirming that non-response bias does not impact the research findings (Armstrong & Overton, 1977).

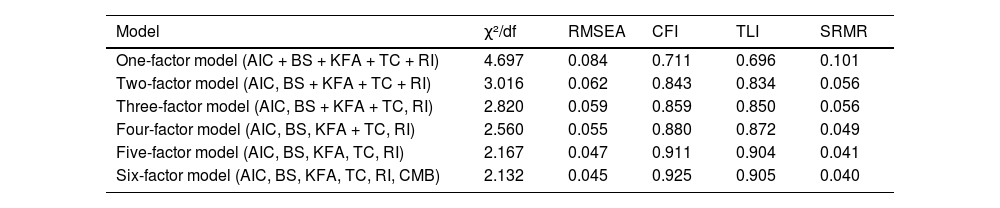

Meanwhile, this study implemented procedural and statistical remedial measures to ensure that CMB would not influence the results (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Procedurally, the study assured participants that there were no right or wrong answers and that their responses would remain anonymous. Additionally, data collection was conducted in stages. In the first stage, CEOs and CTOs evaluated AI capability, boundary-spanning search, knowledge field activity, and tech-for-good culture. One month later, CEOs and R&D managers assessed RI. For the statistical analysis, this study initially employed the Harman’s single-factor test to check for CMB. The results indicated that the variance explained by the first factor was 19.194 %, which is below the threshold of 40 %. Subsequently, this paper conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), with the results presented in Table 4. Compared to other models, the measurement model developed in this study demonstrates better fit indices, all of which meet the required standards (χ2/df = 2.167; RMSEA = 0.047; SRMR = 0.041; CFI = 0.911; TLI = 0.904). Using the Harman single-factor method based on CFA (Podsakoff et al., 2003), all items were assigned to a single latent variable to develop a one-factor model for estimation. The fit results (χ2/df = 4.697; RMSEA = 0.084; SRMR = 0.101; CFI = 0.711; TLI = 0.696) suggest that this model is significantly inferior to the measurement model. Moreover, employing the CMB factor method (Podsakoff et al., 2003), CMB was incorporated as a latent factor into the original measurement model, with all other items linked to this CMB factor. The model fit was then assessed using CFA. Compared to the measurement model, the difference in RMSEA between the two models was 0.002 (0.047 - 0.045), and the difference in CFI was 0.014 (0.925 - 0.911), both of which are below the threshold of 0.050 (Little, 1997). In summary, this study did not exhibit significant CMB.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

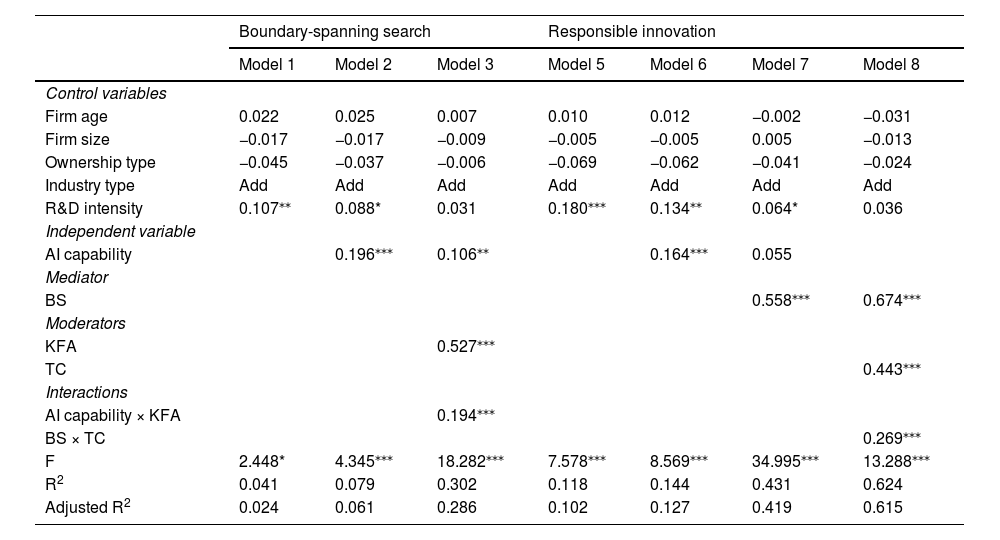

To verify the proposed hypotheses, this study utilized SPSS 26.0 to conduct hierarchical regression analysis, with the results shown in Table 5. Model 5 illustrates the regression model of control variables on RI, while Model 6 depicts the primary effect model of AI capability on RI. The findings from Model 6 indicate that AI capability has a positive influence on RI (β = 0.164, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H1.

Results for regression analysis.

Note(s): *p < 0.05; ⁎⁎p < 0.01; ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.001. Coefficient estimates of ownership dummies are not reported.

The mediation effect was demonstrated by Baron and Kenny (1986). Model 2 demonstrates that AI capability has a significant positive impact on boundary-spanning search (β = 0.196, p < 0.001). Model 7, which includes both AI capability and boundary-spanning search as independent variables, shows that boundary-spanning search significantly and positively influences RI (β = 0.558, p < 0.001). However, the relationship between AI capability and RI is not significant, indicating a full mediation effect. Therefore, this study supports H2. To further investigate the mediating role of boundary-spanning search, the bootstrap method was employed, following Hayes’s (2012) recommendation, with 5000 iterations conducted. The results revealed that the mediating effect of AI capability through boundary-spanning search on RI was 0.224, with a 95 % confidence interval of [0.078, 0.374], which does not include 0, indicating a significant mediation effect. Thus, H2 is reconfirmed.

Moderating effectsBefore conducting hierarchical regression, this study mean-centered AI capability, knowledge field activity, boundary-spanning search, and tech-for-good culture to construct interaction terms, thereby mitigating multicollinearity issues (Aiken & West, 1991). The results of Model 3, presented in Table 5, indicate that the interaction between AI capability and knowledge field activity is positively correlated with boundary-spanning search (β = 0.194, p < 0.001). These findings confirm that knowledge field activity positively moderates the relationship between AI capability and boundary-spanning search, thereby supporting H3a. Similarly, Model 8 shows a significant positive interaction between boundary-spanning search and tech-for-good culture on RI (β = 0.269, p < 0.001). This suggests that tech-for-good culture positively moderates the relationship between boundary-spanning search and RI, thereby supporting H4a.

Next, to further probe the significant interaction effects, simple slope analyses were conducted following Dawson and Richter’s (2006) method. The moderating relationships were plotted using values one standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderators (see Figs. 2 and 3). The findings indicate that, first, when the level of knowledge field activity is high, AI capability exerts a stronger influence on boundary-spanning search. Additionally, when the tech-for-good culture is elevated, boundary-spanning search has a more significant impact on RI. In summary, these results further validate the propositions outlined in H3a and H4a.

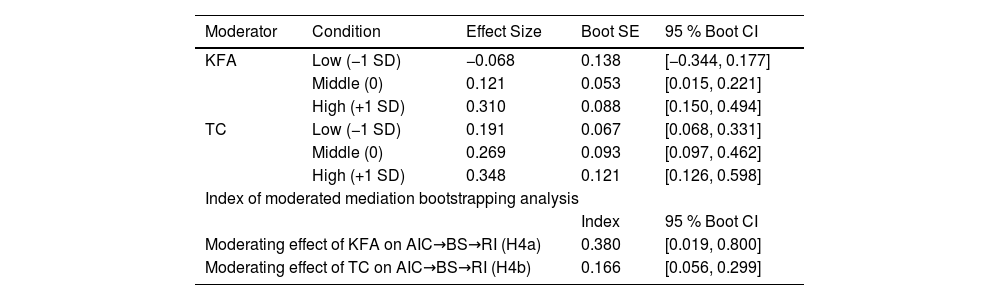

This study then employed the Bootstrap method to verify the moderated mediation effects of knowledge field activity and tech-for-good culture (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). Specifically, it aimed to analyze the mediating role of boundary-spanning search in the relationship between AI capability and RI, considering varying levels of knowledge field activity and tech-for-good culture. Table 6 illustrates that when the level of knowledge field activity is low, the indirect effect of AI capability on RI through boundary-spanning search is −0.068 (CI = [−0.344, 0.177]). Conversely, when the level of knowledge field activity is high, the indirect effect of AI capability on RI through boundary-spanning search increases to 0.310 (CI = [0.150, 0.494]). Additionally, the index of moderated mediation for knowledge field activity is 0.380, with a confidence interval of [0.019, 0.800], further confirming the significant moderating effect of knowledge field activity and thereby supporting H4a. Similarly, concerning tech-for-good culture, the results indicate that the indirect impact of boundary-spanning search is significant at one standard deviation below the mean, at the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean. Moreover, as the level of tech-for-good culture increases, the indirect impact becomes even more pronounced. Furthermore, the tech-for-good culture index is 0.166, with a confidence interval of [0.056, 0.299], thus providing further support for H4b.

Conditional indirect effect of AIC on RI through BS at different levels of KFA and TC.

Note. Bootstrap resample = 5000. Conditions for the moderators are the mean and plus/minus one standard deviation from the mean. SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

As the book The Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age clarifies to people in the technological age, “a sense of responsibility is essential in an age of corruption” (Gray, 1988). Therefore, holders of AI capabilities must assume ethical obligations commensurate with the influence of the technology. Building on this widely discussed issue as a theoretical foundation, this study adopts the KBV to examine how AI capability influences RI in high-tech SMEs and the mechanisms through which this relationship operates. Based on empirical data from 520 Chinese high-tech SMEs, the research findings support the conceptual model and hypotheses proposed in this study and yield valuable conclusions.

First, AI capability has a significant positive impact on RI of high-tech SMEs. While existing literature primarily focuses on the impact of AI capability on innovation efficiency (Abou-Foul et al., 2023; Al Halbusi et al., 2025), few studies have empirically examined the mechanisms through which it influences responsibility dimensions during innovation processes. This study extends previous research by demonstrating that advanced AI capability can systematically reduce ethical risks within innovation workflows.

Second, boundary-spanning search plays a fully mediating role in the relationship between AI capability and RI. This finding indicates that improving AI capability alone does not automatically ensure that innovation activities adhere to ethical standards or social responsibility requirements. Instead, RI practices can only be achieved through active boundary-spanning knowledge search and collaborative integration. This conclusion aligns with the perspective of Buhmann and Fieseler (2021), who argue that knowledge about the social impact and ethical risks of AI exists not only within technology developers but also among multiple stakeholders affected by AI systems. Therefore, enterprises need to acquire heterogeneous knowledge through boundary-spanning search to bridge the cognitive gap between AI capability and RI.

Third, knowledge field activity and tech-for-good culture respectively moderate the relationship between AI capability and boundary-spanning search, and the relationship between boundary-spanning search and RI. Specifically, knowledge field activity functions as an external trigger mechanism that significantly enhances the empowering effect of AI capability on boundary-spanning search by promoting inter-organizational knowledge flow and facilitating the reconstruction of cognitive frameworks. Meanwhile, a tech-for-good culture serves as an internal normative mechanism that effectively directs boundary-spanning search toward RI by filtering knowledge sources that align with social values through ethical standards. Additionally, both factors moderate the mediating role of boundary-spanning search between AI capability and RI.

Theoretical implicationsThis study makes several significant theoretical contributions to the literature. First, AI has become a crucial enabling tool for organizations to enhance their innovation capabilities (Ameen et al., 2022; Pagani & Champion, 2023). However, recent studies indicate that the availability and replicability of AI technology are increasing, making it difficult for AI technology alone to serve as a source of sustainable competitive advantage for enterprises (Mikalef & Gupta, 2021). This debate underscores the theoretical significance of researching AI capabilities. In response, this study addresses the call by Mikalef and Gupta (2021) by providing new insights into the relevant literature through an in-depth examination of the mechanisms underlying AI capability. Furthermore, existing literature has paid insufficient attention to the ethical integration of AI-driven innovation processes (Kumar et al., 2025), particularly within high-tech SMEs, where balancing technological innovation with social responsibility remains an unresolved research gap. To address this issue, the present study focuses on the relationship between AI capability and RI, revealing AI’s potential to embed ethical considerations and create social value. This research not only expands the scope of AI capability studies and enriches prior research on RI but also contributes to the ethical discourse surrounding AI-driven innovation.

Second, by examining the mediating role of boundary-spanning search, this study uncovers the “black box” in the relationship between AI capability and RI in high-tech SMEs, thereby deepening the understanding of the underlying internal mechanisms. RI requires not only technical feasibility but also alignment with social values (Stilgoe et al., 2013). This necessitates that enterprises systematically acquire and integrate diverse knowledge, such as ethical standards, user needs, and cross-domain technologies. Grounded in the KBV, this study emphasizes the importance of boundary-spanning and its bridging role between technological innovation and social value, thus contributing to interdisciplinary literature. Furthermore, it validates the applicability of the KBV in digital contexts (Al Halbusi et al., 2025) and innovatively applies this framework to explore the value realization mechanisms of RI.

Third, by developing a dual-regulation mechanism of "knowledge field activity—tech-for-good culture", this study systematically explains the boundary conditions of AI capability’s influence on RI of high-tech SMEs and expands the theoretical explanatory power of the KBV in dynamic environments. On one hand, this theoretical development responds to Zhang and Fan’s (2024) call for research in the knowledge field within the context of enterprise digital transformation. This paper introduces knowledge field activity as an external moderating factor to explain how interactions within the knowledge environment influence the knowledge search process. On the other hand, based on the synergy between internal and external environments, this study integrates Rana et al.’s (2024) findings on the ethical principles of AI technology and introduces the tech-for-good culture as an internal moderating factor to reveal the influence of organizational culture on the process of knowledge value transformation. This study presents an integrated analytical framework for understanding the situational mechanisms of RI within enterprises by combining internal and external environmental factors.

Managerial implicationsOur study presents several managerial implications for both managers and policymakers. First, enhancing AI capabilities to support RI is essential. For enterprise managers, three key areas require focused investment: 1) Physical resources: High-tech SMEs should prioritize upgrading computing power and networks, optimizing digital infrastructure, accelerating the construction of new data centers, enhancing computing and storage capacities, and reducing AI application costs through modular, pay-as-you-go solutions; 2) Human resources: Given the high talent and technical costs—especially in deep learning and AI fields—faced by SMEs developing AI applications (Ayinaddis, 2025), active collaboration with governments and industry associations is essential to cultivate interdisciplinary professionals with AI literacy and data analysis skills; 3) Intangible resource development: Enterprises should focus on fostering open, collaborative organizational cultures while optimizing management mechanisms. By leveraging AI to redesign business processes, firms can establish a robust organizational foundation for RI. For policymakers, the following measures are recommended: providing tax incentives and special subsidies to reduce infrastructure upgrade costs for SMEs; supporting the development of AI infrastructure service providers; promoting systematic talent development programs; and strengthening technical and ethical education in AI.

Second, strengthening boundary-spanning search to compensate for the shortcomings of RI is essential. Enterprise managers are advised to establish mechanisms for interdisciplinary collaboration, proactively dismantle organizational and knowledge barriers, and engage in deep cooperation with multiple stakeholders, including research institutions, universities, and government agencies. These diverse knowledge acquisition channels can significantly enhance a company’s heterogeneous knowledge base, thereby improving its ability to anticipate potential risks in technological innovation, fostering awareness of its limitations, and ultimately optimizing its innovation strategies accordingly. Recommendations for policymakers include creating a platform to share scientific and technological resources and developing targeted support policies —such as innovation vouchers and technology subsidies—for SMEs to alleviate the financial burden associated with boundary-spanning search.

Third, activate knowledge ecosystems and cultivate a tech-for-good culture. Recommendations for enterprise managers focus on two key aspects: on the one hand, organizations should establish structured public engagement platforms (e.g., consensus-building meetings and public discussion forums) to facilitate dialogue about the ethical, legal, and societal impacts of technological innovation. In environments with underdeveloped knowledge ecosystems, parallel efforts should prioritize investment in knowledge management infrastructure (e.g., knowledge bases and collaboration tools) to enhance ecosystem vitality. On the other hand, managers should proactively embed integrate the tech-for-good philosophy into cultural values. This requires developing a nuanced understanding of users’ and society’s ethical needs, enabling the identification of innovative opportunities that combine commercial value with social value. Recommendation for policymakers is to encourage enterprises to establish public participation mechanisms and promote social dialogue on technology ethics, while providing policy guidance to support enterprises in exploring innovative models.

Limitations and future researchThis study has the following limitations and future research directions: First, the empirical context is geographically bounded, as the data were collected exclusively from high-tech SMEs in China. Consequently, the findings may be influenced by specific institutional environments and cultural characteristics. Future research could select countries/regions with significantly different institutional environments to verify the moderating role of cultural dimensions on the relationship between AI capability and RI through cross-cultural comparisons, thereby clarifying the external validity boundaries of the findings. Second, the sample selection has limitations, with potential sampling bias being a primary concern. Since the data were collected from MBA/EMBA student groups via the Credamo platform, caution is required when generalizing the findings to the broader population of high-tech SMEs managers. The external validity of the study may be more applicable to managers and their enterprises with similar educational backgrounds and management philosophies. Future research could adopt more systematic sampling methods, such as obtaining enterprise lists from the National High-Tech Enterprise Certification Directory, local science parks, or industry associations, and employing stratified random sampling to ensure better representativeness in terms of firm age, size, and industry type. Third, the research design lacks sufficient timeliness. Although data were collected in phases, the study did not implement a rigorous longitudinal tracking. Future research should utilize multi-wave panel data (e.g., tracking a company’s AI application across pre-, mid-, and post-implementation phases) combined with time series analysis to dynamically capture the evolving relationship between AI capability and RI. Fourth, the depth of mechanism exploration requires further expansion. The current framework inadequately reveals the intermediate pathways through which AI capability influences RI. Future research could integrate other theoretical perspectives, such as stakeholder theory or institutional theory, to investigate the roles of key moderating or mediating variables. For instance, analyzing how institutional theory explains the ways in which coercive and normative pressures mediate the transmission of AI into RI practices during implementation. Furthermore, future research could adopt a multi-level analytical framework—encompassing micro-level executive characteristics, meso‑level organizational culture, and macro-level industry standards—to systematically uncover the boundary conditions and transmission mechanisms through which AI capability influence RI. Finally, researchers may extend this framework to explore how enterprises can effectively cultivate AI capability through strategic planning, resource allocation, and organizational learning, thereby establishing a foundation for achieving RI.

FundThis research was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (20BGL059).

CRediT authorship contribution statementXinyu Teng: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Xiu-e Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Yijing Li: Writing – review & editing. Yinuo Dong: Writing – review & editing.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the National Social Science Fund of China (20BGL059) for supporting this research.

Xinyu Teng is a lecturer at Business School University of Jinan. Her research focuses on entrepreneurship and innovation management.

Contribution: 1. Have made substantial contributions to conception and design, and acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; 2. Been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Xiu-e Zhang (Corresponding Author) is a professor at School of Business and Management of Jilin University and a researcher at Northeast Revitalization & Development Institute of Jilin University. Her research focuses on entrepreneurship and innovation management.

Contribution: 1. Have made substantial contributions to conception and design; 2. Been involved in revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Yijing Li is a lecturer at School of Economics and Management, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University. Her research focuses on entrepreneurship and innovation management.

Contribution: 1. Have made contributions to acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; 2. Been involved in proofreading this article.

Yinuo Dong is a student at School of Water Conservancy and Environment, University of Jinan. Her research focuses on clean production and ecological civilization.

Contribution: 1. Have made contributions to acquisition of data; 2. Been involved in proofreading this article.