Job crafting is a multidimensional construct rather than a one-dimensional variable. However, prior research often treats it as a holistic concept or examines its impacts through isolated dimensions. Employing action theory and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA), this study explores how the four dimensions of job crafting influence employee performance. Given the growing prevalence of job crafting within digital environments, this study integrates digital transformation and digital leadership as task-related and social environmental factors, respectively, to investigate pathways leading to high performance in the context of work reimagining. The findings indicate that the inclusion of enterprise digital transformation and digital leadership elevates the number of high-performance configurations from two to three. This underscores the role of contextual enablers in facilitating more diverse and flexible routes to high performance. This study offers both theoretical contributions and practical implications.

Job crafting encompasses employees’ proactive, bottom-up initiatives aimed at reshaping their tasks, interpersonal relationships, and cognitive boundaries (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Tims & Bakker, 2010). This process fosters enhanced alignment between job demands and individual values (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Tims et al., 2022). Unlike conventional top-down job design, which primarily depends on managerial control, job crafting offers a more flexible and personalized approach (Mukherjee & Dhar, 2023). It enables organizations to leverage employees’ intrinsic motivation and adaptability in navigating uncertainty (Petrou et al., 2018; Parker et al., 2025). Empirical evidence indicates that job crafting positively impacts employee outcomes, enhancing work engagement (Kuijpers et al., 2020; Nissinen et al., 2022; Mushtaq & Mehmood, 2023), job satisfaction (Kim et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022), and job performance (Tims et al., 2014; Berdicchia & Masino, 2019; Geldenhuys et al., 2020). At the organizational level, job crafting is associated with improved performance (McClelland et al., 2014; Wang, 2020) and enhanced innovation capability (Petrou, 2018; Miao et al., 2023a). Nonetheless, recent studies indicate that job crafting effects are not consistently positive (Lazazzara et al., 2020; Parker et al., 2025). Previous studies have explored the contingencies of job crafting effectiveness by examining moderating variables linked to individual characteristics, motivation, job designs, and social contexts (Hur et al., 2021; Mohd et al., 2023; Vakola et al., 2023; Kang et al., 2023). For instance, job crafting has pronounced positive effects within high-performance work systems (Miao et al., 2023a).

While these studies shed light on the conditions under which job crafting is most effective, several notable limitations remain. First, despite proposed conceptual models delineating the dimensions of job crafting (Zhang & Parker, 2019; Lazazzara et al., 2020), research investigating how these dimensions interact to form coherent behavioral configurations is scarce. This lack of a process-oriented perspective constrains the understanding of job crafting as an integrated system. Second, most studies have focused on the effects of individual dimensions in isolation (Rudolph et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2025), adopting a reductionist approach that neglects the systemic functioning of these behaviors (Du et al., 2021). Furthermore, while prevailing frameworks, such as the job demands–resources model and role-based perspectives, have contributed valuable insights (Tims & Bakker, 2010; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Rudolph et al., 2017; Holman et al., 2024), they insufficiently capture the dynamic and context-dependent nature of job crafting.

Technological advancements, automation, and data-driven decision-making have fundamentally transformed job roles in contemporary digital workplaces, amplifying complexity, uncertainty, and role ambiguity (Wimelius et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2023; Muylaert et al., 2023). Employees encounter unprecedented challenges in continually adapting their tasks, roles, and interpersonal relationships to keep pace with these transformations (Parker et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2019; Park & Park, 2023). Understanding how job crafting operates as a performance-sustaining mechanism in such dynamic environments is becoming increasingly important. Concurrently, digital technologies and digitally enabled leadership styles introduce novel opportunities and resources that facilitate effective job crafting (Jäckli & Meier, 2020; Matsunaga, 2022; Erhan et al., 2022), creating more feasible and impactful proactive adaptations.

Although extant literature emphasizes various positive outcomes associated with job crafting (Nissinen et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022), this study specifically concentrates on employee performance for two primary reasons. First, employee performance directly affects organizational effectiveness and competitive advantage (Lakhal, 2008; Imani et al., 2020), which is particularly salient in contemporary digital environments (Park & Park, 2023). Second, it constitutes the most immediate and sensitive individual-level indicator of how proactive behavioral adjustments manifest as concrete workplace effectiveness (Sitzmann & Bauer, 2025).

Action theory provides a more appropriate framework for the complexities of the digital era, conceptualizing job crafting as a recursive and contextually situated process (Frese & Zapf, 1994; Pels & Kleinert, 2023). Employees engage in continuous interaction with their environment and actively regulate how they interpret and perform tasks, develop interpersonal relationships, and construct meaning structures (Sanz-Vergel et al., 2024). Lazazzara et al. (2020) argued that job crafting must be understood within its specific organizational context. This positions contextual and proactive elements as central to understanding its diverse effects (Dierdorff & Jensen, 2018; Park & Park, 2023). Not all job crafting dimensions contribute equally to performance (Harju et al., 2016; Lazazzara et al., 2020). Task and cognitive crafting are more likely to enhance job meaning and performance, whereas relational crafting tends to facilitate out-of-role behavior (Geldenhuys et al., 2020). These differentiated effects indicate potential synergies or tensions among dimensions and prompt further inquiries into how crafting behaviors influence performance outcomes.

Accordingly, this study adopts a dynamic configurational perspective to investigate job crafting. It integrates action theory (Frese & Zapf, 1994; Pels & Kleinert, 2023) and configurational logic (Park et al., 2020). First, the necessary condition analysis (NCA) was used to examine whether and to what extent the four dimensions of job crafting and digital elements are necessary for achieving high levels of employee performance. Next, fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) was applied to explore how varying combinations of high and low levels across the four job crafting dimensions influence employee performance. Building on this foundation, the configuration model incorporates two additional contextual factors: enterprise digital transformation and digital leadership. These factors enable a deeper understanding of how contextual conditions interact with the four dimensions of facilitative job crafting. Together, they determine the overall effectiveness of employees’ crafting behavior.

This study provides multiple important contributions to the existing literature. First, job crafting is reconceptualized as a dynamic and situationally configured behavioral system that elucidates how employees integrate various crafting dimensions to respond adaptively to performance-related demands. Building upon this process-based perspective, the study incorporates digital contextual variables into the structural configuration of job crafting, demonstrating how external conditions co-shape internal proactive behavior. Finally, job crafting operates through compensatory and non-linear dynamics, wherein different combinations of behavioral elements may function as substitutes for one another, by analyzing performance outcomes across diverse behavioral configurations. This configurational approach advances the theoretical understanding of job crafting and offers new avenues for conceptualizing performance-relevant behavioral architectures in contemporary organizational settings (Ong & Johnson, 2021).

Theoretical background and research frameworkConfigurational effects of job crafting on employee performanceJob crafting provides a bottom-up mechanism through which employees proactively optimize both individual and organizational performance (Rudolph et al., 2017; Demerouti & Bakker, 2023). These proactive modifications of one’s job are typically individualized and exemplify a form of self-initiated work behavior (Parker et al., 2006). Proactive job crafting occurs across diverse industries and hierarchical levels (Berg et al., 2010; Haun et al., 2023; Mushtaq & Mehmood, 2023) and is positively associated with increased work engagement and improved job performance (Bruning & Campion, 2018; Nissinen et al., 2022; Mushtaq & Mehmood, 2023).

Previous research on the relationship between job crafting and performance has been primarily informed by two theoretical perspectives: role-based and resource-based. The role-based perspective, originally proposed by Wrzesniewski and Dutton (2001), posits that employees proactively reshape their work content and transcend predefined task and relational boundaries to construct personal meaning and professional identity through their work. Such modifications facilitate a stronger alignment between the individual and their occupational role, thereby enhancing motivation, self-efficacy, and ultimately performance (Berg et al., 2013). Conversely, the resource-based perspective emphasizes how employees deliberately modify task execution to balance job demands with available resources, mitigate role-related strain, and enhance the effectiveness of resource deployment, thereby fostering improved performance (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Recent research has converged on a four-dimensional model of job crafting that captures the full spectrum of proactive employee behaviors by building upon and integrating insights from these two perspectives. Bindl et al. (2019) provided robust theoretical justifications and empirical validation for this model. The research demonstrated that cognitive, task, relational, and skill crafting constitute conceptually distinct dimensions, each characterized by unique motivational antecedents and differentiated organizational outcomes. Adopting this well-established framework, this study systematically employs these four dimensions as the analytical foundation for investigating job crafting. Specifically, the four dimensions are as follows: (1) cognitive crafting involves reinterpreting one’s work to enhance its perceived meaningfulness and purpose; (2) task crafting refers to the proactive modification of the quantity, scope, or structure of work tasks; (3) relational crafting involves reshaping interaction patterns with colleagues, supervisors, or clients; and (4) skill crafting involves the acquisition and application of new competencies to improve effectiveness at work. Bindl et al. (2019) conceptualized and validated this four-dimensional structure, providing a theoretically rich and analytically robust lens for examining the heterogeneity and configurational nature of job crafting behaviors.

To better comprehend the dynamic interrelations among these dimensions, the present study employs action theory (Frese & Zapf, 1994), which emphasizes proactive behavior as a continuous, goal-oriented process (Pels & Kleinert, 2023). According to action theory, employee behavior unfolds as a dynamic process in which individuals actively interact with their environment and continuously adjust task goals and action strategies (Nitsch & Hackfort, 2016; Pels & Kleinert, 2023).

Employees can achieve high levels of performance through various job crafting strategies within this dynamic interaction process, without the necessity of activating all dimensions simultaneously. This flexible deployment of strategies reflects both the behavioral diversity among employees in real-world contexts and the inherently dynamic and multifaceted nature of job crafting as a goal-directed action process. Employees may derive a sense of meaning and purpose through cognitive crafting, which can enhance work engagement and foster autonomous motivation, ultimately improving performance (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). This intrinsic sense of meaningfulness can sustain proactive motivation and support the maintenance of high levels of performance (Bruning & Campion, 2018; Geldenhuys et al., 2020). Alternatively, performance gains may be achieved through a primary focus on task crafting or skill crafting, both of which directly influence task execution. Task crafting allows employees to better align personal resources and capabilities with role expectations, thereby increasing efficiency, minimizing workload strain, and improving overall task performance (Tims & Bakker, 2010; Petrou et al., 2018; Rudolph et al., 2017). Similarly, skill crafting entails the proactive development or refinement of individual competencies, enabling more adaptive and effective responses to task demands, thereby supporting continuous improvement in performance (Berg et al., 2013; Demerouti et al., 2015; De etal., 2025). Furthermore, employees may build robust and resource-rich social networks that provide both instrumental support and performance-relevant feedback through relational crafting. By proactively reshaping interaction patterns with colleagues, supervisors, or clients, employees may gain access to social resources, emotional support, and developmental feedback, and improve flexibility and adaptability in task execution (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

In summary, each job crafting dimension or combination thereof may contribute to performance outcomes either independently or synergistically, through distinct pathways and in specific contextual conditions. These combinations underscore the dynamic and complex nature of how job crafting behaviors affect individual performance outcomes. Collectively, the four dimensions, as conceptualized in comprehensive theoretical models (Bindl et al., 2019), constitute an integrated and evolving behavioral system rather than isolated actions, implying the presence of complex combinational effects on performance. Conversely, failure to proactively regulate or reconfigure these dimensions may disrupt productive self-regulatory functioning and increase the likelihood of performance decline.

Building upon the integration of action theory (Frese & Zapf, 1994; Pels & Kleinert, 2023) and a configurational approach, this study is primarily driven by the following two pivotal research questions:

Research question 1.How do employees’ job crafting behaviors (comprising cognitive, task, relational, and skill crafting) coalesce into distinct dynamic configurations that impact performance? Specifically, do these configurations require the concurrent activation of all four dimensions, or can different subsets of dimensions constitute effective pathways to high performance, whereas consistently low levels across dimensions may lead to low performance?

Job crafting within digital leadership and organizational digitizationAccording to action theory, individual behavior does not occur in isolation; rather, individuals engage in continuous interaction with their external environment, adapting and reshaping it through ongoing adjustments (Kulik et al., 1987; Frese & Zapf, 1994). As a targeted form of proactive employee behavior, job crafting involves active modification of tasks, relationships, cognitions, and skills to dynamically accommodate environmental changes (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). This process does not transpire in a vacuum but is deeply embedded within specific organizational contexts, with its effects contingent upon situational opportunities and constraints (Parker et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2019; Park & Park, 2023). Accordingly, contextual factors must be systematically integrated into analyses that examine how job crafting influences performance. Johns (2006) defines context as the opportunities and constraints in the organizational environment, categorizing it into three broad types: task context, social context, and physical context. Task context comprises elements such as job autonomy, task uncertainty, accountability, and access to resources (Dierdorff et al., 2009). Social context includes social structures and interpersonal influences (Simard, 2017), whereas physical context includes environmental characteristics such as workplace temperature, lighting, and ambient noise levels (Johns, 2006).

Based on Johns’s (2006) categorization of contextual factors, this study focuses on the task and social environments in which job crafting occurs. The physical context, including temperature and lighting, is considered less relevant to the cognitive and relational mechanisms underlying employee crafting behaviors and is therefore excluded from the conceptual model. In line with this reasoning, enterprise digitalization is employed to represent the task context, whereas digital leadership represents the social context. These two contextual features are examined to understand how they influence the behavioral configurations through which job crafting contributes to employee performance.

In an era marked by accelerating digital transformation, employees are confronted with significant changes to their work environments (Wang et al., 2025). As noted by Van et al. (2017), digital transformation expedites technological innovation and reorients organizational operations toward data-driven decision-making. These shifts fundamentally reshape work processes, increase task complexity, and heighten uncertainty levels (Liu et al., 2023), altering the task environment in which employees operate. Although uncertainty associated with organizational change can yield both beneficial and adverse consequences (Liu et al., 2024), employee-initiated job crafting, which is generally associated with enhanced performance, may prove insufficient in digitally dynamic contexts. Employees frequently encounter technological pressure, role ambiguity, and adaptation challenges in such an environment (Wimelius et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2023; Muylaert et al., 2023). In these conditions, supportive environmental conditions are critical for enabling effective crafting behavior.

Digital leadership constitutes a key element of the social context among such enabling factors (Banks et al., 2022). Leaders equipped with strong digital competencies help employees manage uncertainty by communicating a clear vision for technological change (Matsunaga, 2022). They provide consistent psychological support, foster autonomy, and promote an organizational climate conducive to experimentation and innovation (Jäckli & Meier, 2020; Erhan et al., 2022). These socially embedded leadership practices influence interpersonal dynamics and clarify organizational expectations, thereby reducing ambiguity and enabling employees to proactively engage with their roles (Jäckli & Meier, 2020; Zhu et al., 2022).

This study investigates the interaction between these contextual factors and the four dimensions of job crafting: task, relational, cognitive, and skill, to elucidate how enterprise digitalization and digital leadership influence employee performance through specific job crafting pathways. Rather than serving as passive background conditions, these contextual elements actively shape the mechanisms through which employees restructure their work. Employees in highly digitalized organizations are compelled to continuously adjust their understanding of job content, role expectations, performance standards, and organizational values in response to emerging technologies and digitally mediated workflows (Lazazzara et al., 2020; Omachi et al., 2024). Effective job crafting enhances employees’ sense of meaning and purpose at work, thereby increasing engagement and performance (Demerouti & Bakker, 2023). However, cognitive crafting may become fragmented or transient in the absence of a clear direction and purpose (Bruning & Campion, 2018), diminishing its capacity to engender sustained behavioral change (Geldenhuys et al., 2020). Under conditions of strong digital leadership, managers assist employees in effectively clarifying cognitive focus and prioritizing effectively through strategic communication and emotional support, thereby amplifying the positive effects of cognitive crafting on performance (Zhu et al., 2022).

Employees operating in highly digitalized environments are better equipped to engage in task crafting following cognitive adjustments. They can more adeptly interpret digital demands and proactively adapt task schedules and workflows with more refined cognitive frameworks. Real-time feedback and automated prompts from digital systems provide timely guidance, facilitating continuous refinement of task execution and performance enhancement (Bruning & Campion, 2018). Nevertheless, digital transformation frequently entails process standardization and centralized decision-making (Liu et al., 2023). Although these changes enhance efficiency, they may concurrently constrain the autonomy of employees in task modification (Abdulkareem et al., 2024). In such contexts, digital leadership becomes vital. Managers who integrate technological acumen with business and strategic insights can empower employees by fostering autonomy-supportive structures and reinforcing work meaningfulness (Zhu et al., 2022). Such a supportive environment sustains cognitive focus while enabling task crafting to emerge as a pivotal strategy for navigating digitalized work demands.

Relational crafting, defined as employees’ proactive modification of work relationships to enhance collaboration and mutual support (Bindl et al., 2019), is becoming increasingly significant within digital work environments. Cloud-based platforms and enterprise communication tools facilitate expanded cross-functional connectivity, allowing employees to access distributed expertise and cultivate informal support networks (Bandelj, 2020). These interactions promote information exchange, foster knowledge sharing, and improve coordination—factors essential for performance in dynamic digital contexts (Bruning & Campion, 2018). Decreased face-to-face interaction can attenuate relational cues and trust, thereby increasing the risk of miscommunication and coordination difficulties (Geldenhuys et al., 2020). In the absence of managerial support and clear contextual framing, relational crafting efforts may fail to yield meaningful social capital. Digital leadership is instrumental in addressing these challenges. Leaders who clearly communicate a shared vision, promote inclusive digital norms, and advocate for distributed collaboration fortify the relational infrastructure vital for effective job crafting (Plekhanov et al., 2023). Through such support, relational crafting emerges as a strategic mechanism to navigate complex and evolving organizational systems.

Skill crafting has become increasingly critical in the context of the transformation of digital technologies in organizational processes. Employees must master new digital tools, integrate advanced systems, and adapt to rapidly changing digital workflows (Kim & Leach, 2020). These requirements present opportunities for continuous learning, enabling individuals to enhance their competencies and sustain professional relevance during shifting role expectations. However, the accelerated pace of technological innovation increases the risk of skill obsolescence. Employees may face challenges adapting to changes without sufficient support structures or sustained motivational drivers, leading to diminished confidence and declining performance (Li et al., 2022). Moreover, skill crafting initiatives may become fragmented when learning lacks coherent structure or perceived relevance. Digital leadership serves a crucial enabling role within this context (Zhu et al., 2022). Managers facilitate effective skill crafting by demonstrating the use of digital tools, encouraging upskilling, and instituting structured opportunities for learning and growth (Plekhanov et al., 2023). These actions translate abstract skill requirements into concrete, attainable objectives, while their technical competence reinforces the organizational commitment to workforce development.

In summary, enterprise digitalization and digital leadership, as central task-related and social contextual variables, not only influence employees’ cognitive judgments (Xu et al., 2022) and behavioral tendencies (Omachi et al., 2024) but also interactively shape employees’ motivational drivers (Jäckli & Meier, 2020; Erhan et al., 2022), strategies (Liu et al., 2023), and pathways in job crafting. In the current digital and volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) environment, job crafting performance indices transcend traditional linear models (Shet, 2024). Rather, these performance outcomes are shaped by interdependent factor configurations (Fiss, 2011). For example, high digitization levels alone may be insufficient to promote effective job crafting without strong digital leadership. Competent digital leadership can foster performance through cognitive and relational crafting mechanisms, even with moderate digitization.

This complexity underscores the inadequacy of linear explanatory models. Therefore, it is imperative to re-evaluate the conditions and mechanisms underlying employee-initiated behaviors from a configurational perspective. Although prior studies have examined select antecedents of proactive behaviors in digital environments (Nöhammer & Stichlberger, 2019; Feng & Liu, 2024), they provide limited theoretical insight into how distinct configurations of job crafting dimensions influence performance under varying task-related and social conditions. Existing theories insufficiently address which job crafting dimensions configurations optimize employee performance across different levels of digital transformation. Therefore, this study adopts a theory-driven exploratory approach (Ong & Johnson, 2021) and poses the following research question:

Research question 2.How do varying levels of enterprise digital transformation (task context) and digital leadership (social context) influence distinct configurational pathways among cognitive, task, relational, and skill crafting dimensions toward employee performance?

MethodologyData collectionData were collected from 52 organizations identified as actively undergoing digital transformation between October and December 2024. All participating organizations are located in Beijing and maintain long-standing university-industry partnerships, regularly engaging in student training programs and collaborative academic research projects. Each organization provided informed consent for the inclusion and analysis of the survey data used in this study.

Organizations meeting the inclusion criteria were identified through a two-step procedure. Initially, student interns conducted systematic observations of digitalization-related practices within their host organizations. These included the implementation of enterprise digital platforms (e.g., ERP, CRM, and automated HR systems), intelligent workflows, and platform-enabled cross-functional communication tools. Observations were documented using a standardized checklist to ensure consistency and comparability. Follow-up interviews with HR representatives were conducted to validate the practices initially observed. The interviews focused on organizational strategies for digital transformation, investments in digital infrastructure, integration of data analytics into core business operations, and initiatives aimed at enhancing employees’ digital competencies. To mitigate potential response bias, HR representatives were restricted to verifying organizational practices documented by the interns. University mentors supervised both stages to ensure the validity of interns’ assessments and the overall sample quality. Organizations meeting at least two of the following four criteria were included: (1) organization-wide implementation of integrated digital systems; (2) operational dependence on automation, AI, or analytics-driven decision tools; (3) presence of digital transformation objectives in strategic planning documents; and (4) active employee training programs focused on digital technologies. The final sample comprised manufacturing (17 %), information technology and software services (31 %), professional and business services (23 %), finance and insurance (13 %), and cultural and creative industries (15 %). Based on the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) employee-based classification system, the majority were classified as medium-sized enterprises (54 %, with 100–500 employees), followed by large enterprises (27 %, > 500 employees) and small enterprises (19 %, < 100 employees). The average organizational age was approximately 10.2 years (SD = 2.8).

The survey was administered on-site using electronic questionnaires via the Credamo platform, which supported survey design, link distribution, and data management. Each student intern recruited five colleagues from different departments within their host organization to participate at Time 1 (T1). After obtaining informed consent, participants accessed the T1 survey through WeChat. Data collected at T1 included employee perceptions of enterprise digital transformation, digital leadership, and the four dimensions of job crafting. Of the 260 employees who agreed to participate, 249 valid responses were retained after the initial data screening. Four weeks later, job performance data were collected from each participant’s immediate supervisor at Time 2 (T2). To ensure a high-quality response and accurate dyadic matching, university mentors and HR personnel from participating organizations contacted the identified supervisors directly. As part of an ongoing university-enterprise collaboration initiative, they provided a clear explanation of the study’s purpose and addressed potential concerns regarding subordinate evaluation to encourage cooperation. HR personnel were not involved in administering the employee or supervisor surveys. Subsequently, the interns invited their respective supervisors to complete the T2 evaluation, delivered the electronic questionnaire link in person, and assisted with the consent and login details via WeChat. Of the 207 supervisor evaluations returned (with a response rate of 83.13 %), the final matched dataset comprised 194 employee-supervisor dyads across both time points after excluding 13 incomplete or invalid cases.

The final valid sample comprised employees with a mean age of 35 years (SD = 4.11), with 57 % identified as female. Regarding occupational roles, 106 participants were general staff (54.6 %), 22 were front-line supervisors (11.3 %), and 28 were middle managers (14.3 %). In terms of educational background, 10 (5.2 %) participants held postgraduate degrees or higher, 109 (55.7 %) held bachelor’s degrees, and 74 (39.1 %) had an associate degree or lower qualification.

MeasurementsAll constructs were measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Detailed descriptions of each measure are provided below.

Job crafting was measured at Time 1 using the 16-item, four-dimensional scale developed by Bindl et al. (2019). The cognitive crafting dimension included four items (e.g., "I thought of some new ways to look at my whole job"), with a Cronbach’s α of 0.921. Task crafting comprised four items (e.g., "I improve the complexity of tasks by changing the structure or order of tasks"), with a Cronbach’s α of 0.846. The relational crafting dimension also consisted of four items (e.g., "I am actively meeting new people at work"), yielding a Cronbach’s α of 0.929. The skill crafting dimension included four items (e.g., "I look for opportunities to expand my general skills at work"), demonstrating a Cronbach’s α of 0.917.

Enterprise digitalization was assessed at Time 1 using a three-item scale adapted from Chi et al. (2022). A sample item is, "Companies are using digital technology to change their business processes." The scale demonstrated strong reliability in the current study (Cronbach α = 0.919). Enterprise digitalization was measured from the subjective perspectives of employees, as their perceptions of digitalization more directly influence proactive behaviors and performance. Moreover, the reporting standards of objective infrastructure data often vary substantially across organizations, making meaningful comparisons difficult.

Digital leadership was measured at Time 1 using the six-item Digital Cognitive Practical Ability dimension from the scale developed by Zhang and Zheng (2023). A sample item is, "My leader is able to go into the front line of work and determine the actual difficulties of the enterprise in the process of digital transformation." The scale demonstrated excellent reliability in the current study (Cronbach’s α = 0.963).

Job performance was measured at Time 2 using the 10-item scale developed by Borman and Motowidlo (1997), which includes items such as "I can complete the task and meet the requirements of the job in the time allotted." In the current study, the scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.876.

Analysis method: Necessary condition analysis and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysisThe QCA method, introduced by Ragin 2008, employs set theory and Boolean algebra to examine how combinations of multiple antecedent variables influence an outcome, thereby revealing the complex causal relationships underlying organizational and social phenomena (Ragin, 2014). While QCA can qualitatively identify whether antecedent variables are necessary for an outcome, it does not quantify the extent to which these conditions are required. To address this limitation, Dul (2020) developed the NCA method, which enables researchers to quantitatively assess the degree to which a given antecedent must be present for the outcome to occur.

The integration of NCA with QCA provides a more comprehensive analytical framework, as evidenced by an expanding body of empirical research. For example, studies in entrepreneurship (Reyes-Mercado & Larios Hernandez, 2025; Hu et al., 2024) and policy analysis (Ding, 2022) have combined the two methods by first identifying necessary conditions quantitatively through NCA and then exploring sufficient configurations of conditions using QCA. This integrated approach strengthens causal inference by assessing the extent to which antecedent variables must reach specific thresholds to constitute the necessary conditions for an outcome. Incorporating NCA thus enhances and complements the methodological rigor of QCA, yielding more robust and nuanced conclusions (Dul, 2016a, 2016b).

As environmental complexity increases, traditional analytical approaches that focus on the net effects of individual variables or limited interactions often fail to fully explain outcome generation. Consequently, fsQCA has gained widespread adoption in management research (Fiss, 2007; Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Nikou et al., 2024). First, fsQCA employs a case-based approach, allowing systematic analysis of comparative data from multiple cases while accounting for their inherent heterogeneity and complexity (Greckhamer et al., 2018). Second, fsQCA investigates the joint effects of configurations of antecedent conditions on an outcome, enabling the identification of multiple, distinct causal pathways leading to a complex phenomenon, unlike quantitative methods such as regression analysis, which primarily examine the net effect of independent variables (Gabriel et al., 2015). Additionally, fsQCA addresses causal asymmetry, where conditions that produce the presence of an outcome may differ from those that produce its absence (Fiss, 2007). In this study, job performance was examined under the interplay of the four job crafting dimensions to identify common configurations across multiple cases, thereby elucidating the combinations of conditions sufficient for a particular outcome. Causal asymmetry is indicated, showing that configurations leading to the presence of an outcome differ from those leading to its absence. This principle differs from that of traditional symmetrical analyses. For instance, a significant correlation between entrepreneurial orientation and high performance does not imply that low entrepreneurial orientation causes low performance. Consequently, the relationship between conditions and outcome presence versus absence is asymmetric, and configurations resulting in the absence of high performance must be separately analyzed (Fiss, 2011).

This study employed fsQCA over regression-based interaction analysis because of its superior ability to examine the synergistic effects of multiple antecedent conditions. Several key distinctions justify this approach. First, the two methods are grounded in different philosophical approaches: regression relies on reductionism, deconstructing systems into individual components, whereas fsQCA adopts a holistic perspective, viewing systems as integrated wholes whose collective effects exceed the sum of their parts. This holistic approach enables fsQCA to circumvent the challenges of specifying precise interaction terms in regression without strong theoretical guidance, instead focusing on how overall system outcomes are achieved and under which conditions (Fiss, 2011). Second, the two methods address distinct research questions. While regression primarily examines the net effects of combined independent variables, fsQCA simultaneously considers multiple antecedents within distinct configurations to identify conditions that are sufficient or necessary for an outcome. Given this study’s focus on the complex interplay of four job crafting dimensions and contextual factors influencing performance, fsQCA is particularly well-suited to model such intricate, multi-causal relationships. Moreover, fsQCA can differentiate between core and peripheral conditions, clarify the relative importance of antecedents, and identify multiple equifinal pathways to an outcome-capabilities essential for informing effective performance improvement strategies. Therefore, a configurational approach using fsQCA provides a more appropriate analytical lens for this research.

CalibrationThe fsQCA method requires raw data to be calibrated into set membership scores ranging from 0 (full non-membership) to 1 (full membership), with 0.5 representing the crossover point of maximum ambiguity. This study employed the direct calibration method. Following prior research (e.g., Cangialosi, 2023; Pappas & Woodside, 2021), three calibration anchors were defined based on the sample distribution. Full membership (score = 1) was set at the 80th percentile, the crossover point (score = 0.5) at the 50th percentile (i.e., the median), and full non-membership (score = 0) at the 20th percentile. These anchors were applied to all antecedent and outcome variables. For the outcome variable non-high job performance, calibration was performed by subtracting the high job performance membership scores from 1. This is calculated as 1 minus the high job performance score. To prevent cases with a calibrated membership score of exactly 0.5 from being excluded during the truth table analysis, these scores were adjusted by adding 0.001, resulting in 0.501 (Campbell et al., 2016). Calibration details for all variables are presented in Table 1.

Fuzzy-set membership calibrations.

After calibrating fuzzy-set data, we constructed a truth table and applied Boolean minimization to identify empirically sufficient configurations. This process followed three steps. First, a minimum case frequency threshold was used to ensure empirical relevance. A threshold of 3 was adopted. This retained configurations covering a substantial portion of the sample (at least 75 %) while excluding rare or poorly supported patterns (Du & Jia, 2017). Second, we applied a raw consistency threshold to assess whether each configuration reliably indicates the outcome. In the initial analysis (linking job crafting dimensions to performance), a raw consistency threshold of 0.75 was used. This yielded 13 configurations from an initial pool of 15, covering 190 cases. Third, we applied a Proportional Reduction in Inconsistency (PRI) threshold to prevent contradictory configurations—those simultaneously linked to an outcome and its negation—from being accepted as sufficient. In this study, we adopted two levels of PRI thresholds: 0.5 in the initial analysis and 0.6 in the extended analysis. The choice of 0.5 follows Greckhamer et al. (2018) and reflects the actual structure of the data: a higher PRI of 0.6 would include more configurations (five vs. three) but introduces more marginal paths with low explanatory weight. We therefore report the more parsimonious and stable model at PRI ≥ 0.5 in the main results while also examining PRI ≥ 0.6 for robustness, which identified two additional configurations with comparatively low unique coverage.

In a more complex configurational analysis involving enterprise digital transformation, digital leadership, and job crafting dimensions as antecedents (outcome: job performance), we adopted the following thresholds: a frequency threshold of 3, a raw consistency threshold of 0.80, and a PRI consistency threshold of 0.60 (Ding, 2022). These steps ensured that only robust and consistent configurations proceeded to the final interpretation of causal pathways.

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 2 presents the descriptive statistics for all study variables. To ensure the structural validity of the measurement model and establish discriminant validity among latent constructs, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. This step was particularly important given the study’s Chinese digital context, where the dimensional structure of job crafting and its distinction from digital leadership and transformation have rarely been tested. The measurement model was estimated using CFA in AMOS 24.0, specifying job crafting as a second-order construct comprising four first-order dimensions (task crafting, relational crafting, skill crafting, and cognitive crafting), alongside enterprise digital transformation and digital leadership as separate first-order factors. As shown in Table 3, the six-factor model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 = 1146.819, df = 529, χ2/df = 2.168, CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.904, RMSEA = 0.078) and outperformed the alternative models (p < 0.001), providing empirical support for the proposed measurement structure.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

Note: Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). N = 194.

Results for CFA.

| χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | TLI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seven-factor model | 1146.819 | 529 | 0.078 | 0.915 | 0.915 | 0.904 | 0.0542 |

| Six-factor modela | 1328.609 | 535 | 0.088 | 0.890 | 0.891 | 0.878 | 0.0562 |

| Five-factor modelb | 1361.427 | 540 | 0.089 | 0.887 | 0.887 | 0.875 | 0.0592 |

| Four-factor modelc | 1432.970 | 544 | 0.092 | 0.877 | 0.878 | 0.866 | 0.0584 |

| Three-factor modeld | 1840.667 | 547 | 0.111 | 0.821 | 0.822 | 0.806 | 0.0844 |

| Two-factor modele | 2500.882 | 549 | 0.136 | 0.730 | 0.732 | 0.708 | 0.0939 |

| One-factor modelf | 3541.014 | 550 | 0.168 | 0.587 | 0.589 | 0.553 | 0.1530 |

This model combines Relational crafting, Skill crafting, Task crafting and Cognitive crafting into one factor.

This model combines Relational crafting, Skill crafting, Task crafting, Cognitive crafting and Enterprise digital level into one factor.

This study employed a necessity analysis using the NCA package in R to examine whether any individual condition is necessary for the outcome. NCA not only identifies the necessary conditions but also quantifies their effect sizes, indicating the extent to which a condition constrains the outcome. The methodology incorporates two estimation techniques: ceiling regression (CR) for continuous variables and ceiling envelopment (CE) for discrete variables. A condition is considered necessary only when two criteria are satisfied: the effect size (d) is equal to or greater than 0.1 (Dul, 2016), and the effect size is statistically significant according to a Monte Carlo permutation test (Dul et al., 2020).

Table 4 presents the results of the NCA for individual antecedents. It reports five key indicators (accuracy, upper-left area, range, effect size, and p-value) under both CR and CE estimations. The results show that neither enterprise digital transformation nor digital leadership demonstrates a statistically significant necessity effect (p > 0.05), indicating that these two conditions are not individually necessary for high job performance. While relational crafting, skill crafting, task crafting, and cognitive crafting all yield statistically significant necessity effects, their effect sizes are below the 0.1 threshold. Therefore, none of these conditions alone qualify as necessary for achieving high job performance.

Results of necessity condition analysis using the NCA method antecedent.

Table 5 reports the results of the bottleneck level analysis, which identifies the minimum threshold ( %) of each condition required to achieve a given level of the outcome. For example, reaching 100 % of high job performance would require at least 12.6 % in relational crafting, 18.9 % in skill crafting, 5.1 % in task crafting, and 12.2 % in cognitive crafting. In contrast, no bottleneck thresholds are observed for enterprise digital transformation or digital leadership.

Results of necessity condition analysis using the NCA.

Note: NN indicates that the condition is not necessary for the outcome, based on effect size and significance thresholds.

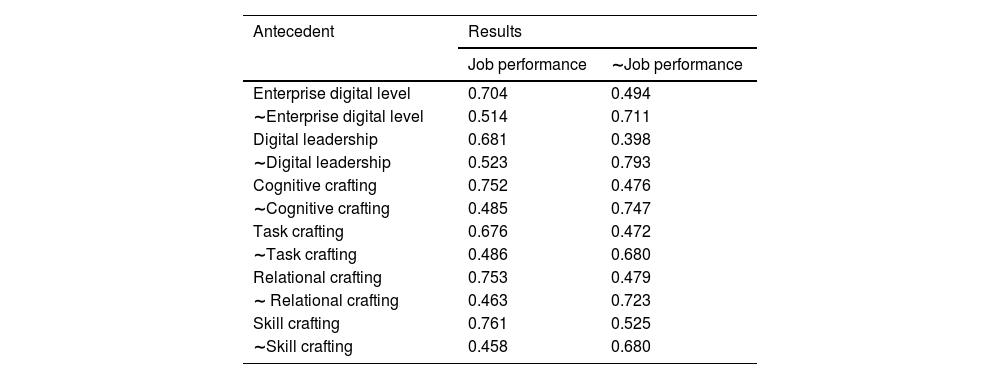

Additionally, a necessity analysis based on the QCA method was conducted. Table 6 shows the consistency scores for each antecedent condition with respect to both high and low job performance. All consistency values are below the 0.90 threshold, which aligns with the NCA results. This further confirms that no single antecedent condition constitutes a necessary condition for job performance.

Results of necessity condition analysis using fsQCA.

The sufficiency analysis was conducted using fsQCA 3.0 to identify the configurational pathways leading to high job performance. In this method, consistency serves as the primary evaluation criterion, analogous to statistical significance in regression analysis, with a score above 0.75 indicating that a configuration can be considered sufficient to produce the outcome. Coverage reflects a configuration’s empirical relevance by quantifying the proportion of the outcome explained by the sufficient condition (Ragin & Fiss, 2008). However, unlike consistency, no universally accepted minimum threshold exists for coverage.

The fsQCA 3.0 generates three solution types: complex, intermediate, and parsimonious, which differ in their logical remainder treatment. Complex solutions exclude all logical remainders, parsimonious solutions include all, and intermediate solutions incorporate only those supported by theory and empirical plausibility. Logical remainders represent unobserved combinations of antecedent conditions. For n conditions, 2ⁿ combinations are theoretically possible; however, only M combinations are typically observed in empirical data, with the remaining 2ⁿ − M combinations constituting logical remainders (Du & Jia, 2017). Following Ragin and Fiss (2008), the results are reported by distinguishing core from peripheral (edge) conditions. A core condition, appearing in both parsimonious and intermediate solutions, reflects strong empirical and theoretical relevance; its presence is denoted by a filled circle (●) and absence by a crossed circle (⨂). Peripheral conditions appear only in the intermediate solution, indicating secondary importance, with a filled circle indicating high-level presence and a crossed circle indicating absence.

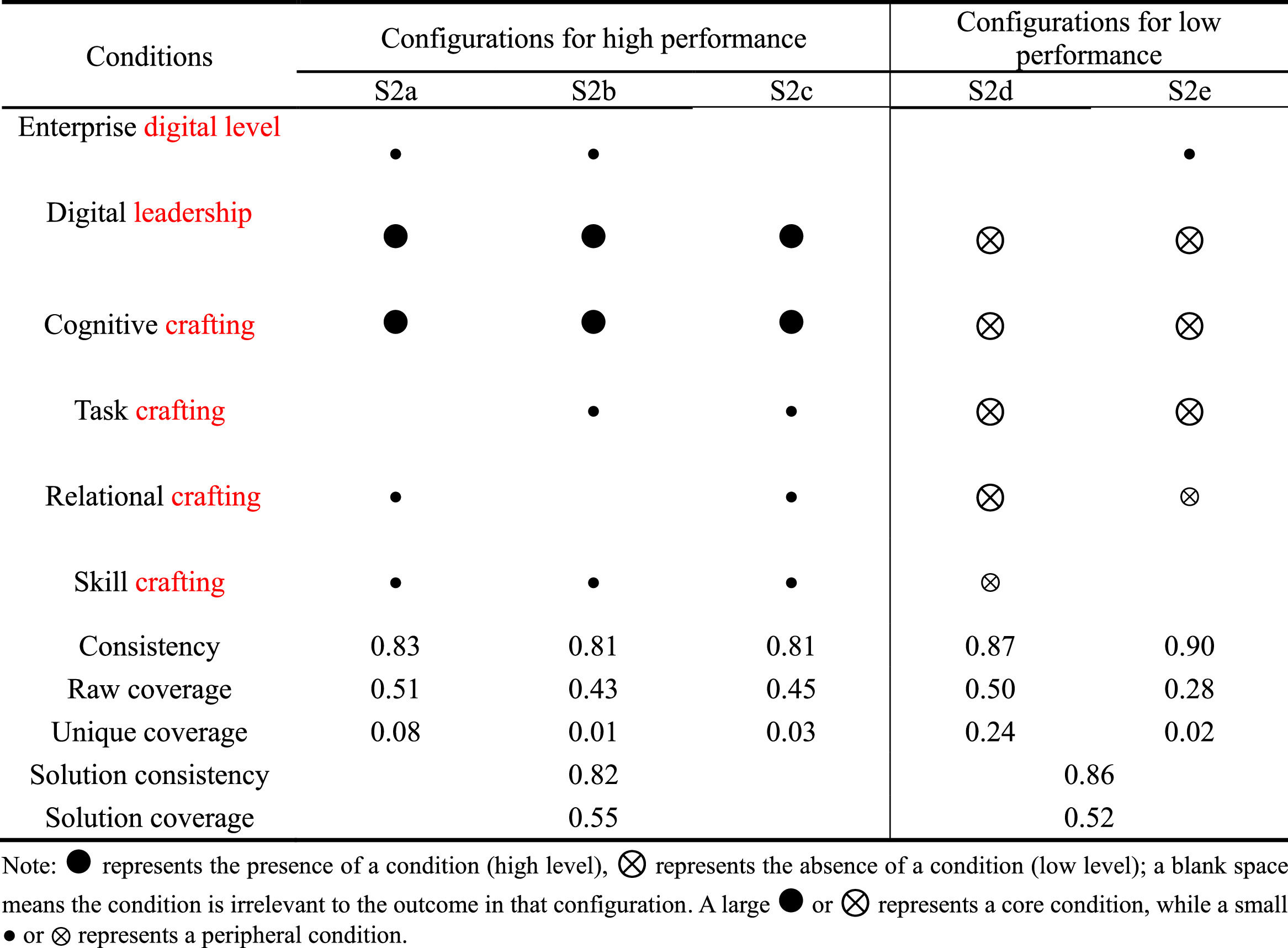

The fsQCA results identified two configuration paths based on the four job crafting dimensions (Table 7). These configurations achieved an overall solution consistency of 0.77, indicating that 77 % of the cases covered by these paths exhibited high job performance. The solution coverage of 0.66 indicates that these two configurations account for 66 % of all high-performance cases. When enterprise digital transformation and digital leadership were incorporated alongside the four job crafting dimensions, three distinct configuration paths were revealed in the full model (Table 8). The overall solution consistency increased to 0.82, indicating that 82 % of cases conforming to these configurations demonstrated high job performance, while the solution coverage of 0.55 indicates that these three paths explain 55 % of all high-performance cases.

Outcome variable analysis: Job performanceThe fsQCA results identified three configurations related to job performance. Configurations S1a and S1b correspond to high performance, with cognitive crafting and relational crafting appearing as core present conditions in both configurations. In S1a, skill crafting is a peripheral present condition, whereas task crafting is a peripheral present condition in S1b. These peripheral conditions complement the core dimensions in each configuration. Configuration S1c corresponds to low performance, with the absence of all four job crafting dimensions. Specifically, skill crafting is absent at the core, whereas cognitive crafting, relational crafting, and task crafting are absent at the peripheral level. This low-performance configuration achieves a consistency score of 0.86 and a unique coverage of 0.52.

In summary, cognitive crafting and relational crafting consistently emerge as core conditions in high-performance configurations, while skill crafting and task crafting function as peripheral conditions with varying presence. These results underscore the configurational nature of job crafting, demonstrating that high performance arises from their specific combinatorial patterns and not from individual dimensions in isolation. Collectively, these findings provide an empirically grounded answer to Research question 1.

Table 8 presents three high-performance configurations (S2a, S2b, and S2c) and two low-performance configurations (S2d and S2e). Digital leadership and cognitive crafting consistently appear as core present conditions across all high-performance configurations. Enterprise digital transformation functions as a peripheral present condition in S2a and S2b, whereas it is absent in S2c. The peripheral conditions across these configurations include task, skill, and relational crafting. Among the low-performance configurations, S2d identifies digital leadership, cognitive crafting, task crafting, and relational crafting as core absent, whereas in S2e, digital leadership, cognitive crafting, and task crafting are core absent, and relational crafting is peripheral absent; enterprise digital transformation is peripheral present, and skill crafting is irrelevant (IRR). The solution coverage is 0.55 for high-performance configurations and 0.52 for low-performance configurations.

These findings offer a structured configurational analysis of how job crafting dimensions and contextual factors jointly influence job performance variations, providing an empirical basis for addressing Research question 2.

DiscussionThis study investigated how different job crafting behavior configurations affect employee performance and how digital contextual factors shape these configurations. The findings advance the literature by showing that job crafting does not operate as a uniform or additive behavior; instead, it manifests as distinct configurations of core and peripheral dimensions that adaptively align with specific situational conditions.

The results indicate that high performance does not necessitate the simultaneous activation of all job crafting dimensions (Lin et al., 2017; Wijngaards et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022), supporting the principle of equifinality in proactive behaviors. Cognitive crafting has consistently emerged as a core condition across all high-performance configurations, underscoring its central role in interpreting work demands and sustaining engagement (Wijngaards et al., 2021). In contrast, relational crafting exhibited greater variability, functioning either as a core condition or being substituted by task or skill crafting. This pattern aligns with Doden et al. (2024), who highlighted the context-dependent nature of relational crafting. Overall, the findings demonstrate that task, relational, and skill crafting can complement or substitute for one another depending on environmental conditions, confirming the configurational logic of trade-offs and synergies in job crafting.

The analysis of digital contextual factors yielded further insights. Incorporating digital leadership and enterprise digital transformation into the configurations increased the number of high-performance pathways from two to three, illustrating how contextual support enables employees to adopt more diverse and tailored strategies for sustaining high performance in dynamic environments (Parker & Grote, 2022). Notably, although overall solution consistency improved, solution coverage decreased, indicating that these digitally enabled configurations are more precise but apply to a smaller subset of employees with higher digital adaptability, extending Liu et al.’s (2024) argument regarding digital readiness as a moderating factor.

The analysis revealed that peripheral conditions became more dynamic within digital contexts. In the job crafting-only model, skill crafting and task crafting exhibited a substitution relationship, with each supporting performance alongside stable core conditions. In contrast, the extended model demonstrated dynamic complementarity between relational and task crafting. For example, in Configuration S2b, task crafting compensated for weaker relational crafting, whereas in S2a, insufficient task structuring was offset by relational crafting. Configuration S2c displays a mixed peripheral structure. These patterns highlight how employees adaptively adjust their strategies based on internal resources and external affordances (Bala et al., 2025), consistent with configurational logic and trade-offs theories in proactive behavior.

By integrating these findings with existing literature, this study demonstrates that the interplay between job crafting and digital context produces distinct performance pathways. This underscores the configurational and dynamic nature of job crafting, illustrating how proactive behaviors adapt to both individual capacities and organizational conditions (Strauss & Parker, 2015).

Theoretical contributionsThis study makes three significant contributions to the literature on job crafting. First, a process-based configurational perspective is introduced by conceptualizing job crafting as a system of interdependent behavioral choices shaped by situational conditions. Previous studies often treat job crafting as a static construct or reduce it to a unidimensional index (Rudolph et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2025). However, this study draws on action theory (Frese & Zapf, 1994) and employs fsQCA to examine how task, relational, cognitive, and skill crafting combine to influence performance. The findings reveal that job crafting operates not through uniform activation of all dimensions but through distinct configurations of core and peripheral behaviors, highlighting it as a situationally assembled process and providing a structured foundation for theorizing how employees align strategies with contextual demands.

Second, the study reconceptualizes the role of context in job crafting research. While traditional studies often treat contextual variables as moderators or background factors (Petrou et al., 2018;Miao, 2023b), few examine context as a structural component of the crafting process. This study incorporates digital leadership and enterprise digital transformation directly into the configuration model as performance-relevant conditions that interact with crafting dimensions. The results reveal that in high-performance configurations, digital leadership consistently aligns with cognitive crafting, whereas digital transformation functions as a peripheral yet enabling factor. These findings advance the person-environment interaction framework, highlighting that crafting effectiveness relies on both individual initiative and employee strategy alignment with organizational conditions.

Third, this study advances the theoretical understanding of equifinality and conditional substitution within the context of job crafting. Multiple high-performance pathways are identified using a configurational approach in which peripheral elements compensate for or reinforce one another when stable core conditions are present. For example, relational crafting can substitute for absent task crafting, whereas in other configurations, skill and task crafting jointly offset limited relational engagement. These findings challenge linear models that assume additive or independent effects across dimensions. Instead, job crafting emerges as a flexible, adaptive system in which employees strategically deploy different behaviors based on internal resources and external conditions, supporting its reconceptualization as an emergent, performance-responsive structure.

Management implicationsThis study offers several actionable implications for organizational leaders and HR professionals seeking to enhance employee performance through job crafting strategies. First, organizations should tailor support resources to the dominant job crafting configurations of employees rather than promoting uniform development across all dimensions. For example, employees operating within cognitive-relational core configurations may benefit the most from coaching, feedback systems, or meaning-centered interventions, whereas those relying on task-skill combinations to achieve performance may require structured training, workflow redesign, or targeted upskilling. Aligning developmental support with configuration profiles can optimize resource allocation and prevent redundant or misaligned interventions.

Second, enhancing digital leadership capacity is critical in the contexts of digital transformation. The findings indicate that digital leadership consistently functions as a core condition in high-performance pathways, particularly when paired with cognitive crafting. Managers must prepare to guide employees through technological transitions, articulate the rationale for change, and support the adaptive reinterpretation of work roles. Digital transformation extends beyond technological upgrades to include employee level behavioral adaptation. Consequently, organizations should invest in both infrastructure and leadership capabilities that facilitate employee sensemaking and role reframing. Developing internal leadership pipelines with digital fluency and relational competence can sustain high-performance job crafting behaviors.

Third, organizations should recognize and leverage functional substitution among peripheral crafting dimensions. The results indicate that when one peripheral dimension (e.g., relational crafting) is constrained, employees can sustain effective performance by activating alternative pathways, such as task or skill crafting. Rather than enforcing rigid competency models, organizations should promote flexible behavioral strategies that allow employees to develop performance-relevant configurations tailored to role requirements and environmental conditions.

Limitations and directions for future researchDespite these contributions, the study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the fsQCA analysis relied on internal calibration based on percentiles of sample distribution. Although this method is widely used and has yielded robust consistency and coverage in the current model, its anchor points are relative to the present dataset, which may limit the comparability and generalizability of the findings across different organizational contexts. Future research could address this limitation by adopting external calibration strategies using theoretically informed benchmarks or by replicating the analysis across multiple samples to enhance robustness.

Second, although a temporal separation between antecedent and outcome variables was introduced to reduce common method bias, cross-sectional designs were used to measure the core constructs. Consequently, the study is unable to capture how job crafting configurations form, evolve, or dissolve over time. Future research could employ longitudinal designs, experience sampling methods, or behavioral trace analysis to uncover the temporal mechanisms through which employees adaptively assemble and adjust crafting strategies in dynamic work environments.

Third, this research incorporated two key contextual conditions—enterprise digital transformation and digital leadership. Although these variables capture important aspects of task and social contexts, they do not represent the full spectrum of contextual influences relevant to job crafting. Additional factors, such as organizational culture, job autonomy, task interdependence, and team climate, may significantly shape behavioral configurations. A cross-level design could be adopted in future research to investigate how institutional conditions and team dynamics collectively influence the formation and evolution of job crafting patterns.

Finally, this study focused on within-level configurations at the individual level. Future research could extend these findings by theorizing and testing multi-level configurational structures in which individual, team, and organizational elements are integrated into performance-relevant behavioral systems. Such investigations would contribute to the development of a more comprehensive and dynamic theory of proactive behavior in contemporary workplaces.

ConclusionsThis study investigated how job crafting configurations shaped by digital contextual factors affect employee performance. Multiple high-performance pathways were identified through a configurational approach, each reflecting distinct combinations of core and peripheral crafting dimensions aligned with organizational conditions. These findings advanced the understanding of job crafting as a dynamic, situationally assembled process, highlighting its configurational rather than uniform nature. They also emphasize the pivotal role of digital leadership in enabling employees to proactively craft their roles within evolving work environments. Future research could extend these insights by examining the temporal evolution of crafting configurations, exploring multi-level dynamics incorporating team and organizational factors, and testing interventions that support flexible crafting strategies across diverse digital contexts.

Ethical approvalThis study has been ethically approved by the institutional review board affiliated with the authors. And this work follows the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consentAll participants provided informed consent prior to their involvement in the study.

CRediT authorship contribution statementZhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Cui: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chai: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Zhiyuan Science Foundation from Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology (Project No. BIPTCSF-2025108).