Entities worldwide continue to engage in knowledge management practices (KMP) and organizational agility (OA); however, little is known about their relationship with firms’ inter-organizational learning (IOL) and innovation speed. Moreover, risk-taking rationales are used as moderators. Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) is used for hypothesis testing. Based on the data obtained from 294 participants based in Lahore, Pakistan, the results show a positive and significant relationship between firms’ KMP and OA, IOL, and innovation speed. Similarly, the results suggest a significant positive effect between IOL and OA. Furthermore, the relationship between KMP and OA is significantly influenced by IOL. Moreover, firms’ rate of innovation plays a significant role in the relationship between KMP and OA. Similarly, a positive correlation exists between organizations’ risk-taking tolerance and OA. Finally, the results show that a higher risk-taking tolerance enhances the connection between IOL and OA. First, this study contributes to the existing academic literature by focusing on predictors determining OA. Second, this article integrates KMP, IOL, innovation speed, and risk-taking tolerance to determine OA. Third, it employs resource-based and knowledge-based view theories. These findings underscore the importance of leveraging knowledge management, organizational flexibility, and risk-taking behaviour to accelerate inter-organizational learning and innovation outcomes. This research offers significant implications for companies seeking to optimize their operational and strategic practices in a dynamic, knowledge-based economy.

Organizations face increasingly complex, dynamic, and uncertain business environments due to the highly turbulent, volatile, and uncertain economic scenarios prevailing in today’s national and supranational contexts (Kraus et al., 2020). Henceforth, it has become increasingly difficult for firms to establish and maintain a competitive advantage that allows businesses to nurture growth and enhance their survivability. Both academic and practitioner discussions emphasize the critical role of knowledge management (KM), as it enables firms to identify and capitalize on emerging opportunities. KM practices are paramount for businesses to address sustainable issues (Broccardo et al., 2025). This, in turn, helps them gain a competitive advantage, acquire strategic resources, and enhance overall performance (Rehman et al., 2022). Specifically, by leveraging KM practices, organizations can facilitate rapid adaptation and foster innovation, thereby enhancing organizational agility (OA) (Bresciani et al., 2022). The above-detailed agility significantly improves a company's ability to endure and thrive during challenging times. Sambamurthy et al. (2003) define OA as a firms’ ability to recognize opportunities in an imperfect market, thereby proactively engaging in behavior to capitalize on them. Specifically, the actions taken by agile firms encompass both physical- and intangible assets, as these entities possess the necessary tools and techniques to apply knowledge and tangible instruments to navigate rapid changes, thereby fostering their future prosperity (Nafei, 2016). Therefore, OA is often perceived as the redesign and restructuring of an organization’s innovation to foster its ability to quickly respond to market changes thereby attaining and enhancing its competitive advantage (Darvishmotevali et al., 2020).

Within the theoretical framework of OA, intellectual thinking emphasizes the pivotal role of an organization’s KM practices and systems in driving innovation (Alhosani & Ahmad, 2024). The foregoing practices support the development of innovative initiatives and are fundamental to maintaining and enhancing a firm's competitive advantage (Motwani & Katatria, 2024; Oliva et al., 2019; Rehman et al., 2022). Fundamentally, identifying, managing, and converting relevant knowledge into valuable insights can significantly enhance an organization’s competitive advantage, thus strengthening the firm's capacity to thrive in increasingly challenging environments (Rehman et al., 2022). In light of the above-detailed notions and their relevance to today’s business environment, both academics and practitioners have begun to conceptualize and develop tools and mechanisms aimed at creating and capturing the necessary knowledge to drive sustainable growth, thereby further emphasizing the significance and relevance of KM and OA in promoting continuous innovation and long-term business success (Bresciani et al., 2022; Darvishmotevali et al., 2020; Mehta & Bharadwaj, 2015; Motwani & Katatria, 2024).

The effective integration of KM within an organization's boundaries primarily relies on the following systems: KM technologies, structure, and culture (Claver‐Cortés et al., 2007; Syed‐Ikhsan & Rowland, 2004). First, establishing a strong KM culture and implementing non-hierarchical and flexible KM structures across all business units enables the optimal utilization of an organization’s knowledge (Choo, 2013). Indeed, empirical evidence suggests that a strong KM culture and structure are critical prerequisites for developing robust social environments that embed knowledge-sharing practices within organizations (Swap et al., 2001). Moreover, Gold et al. (2001) scholarly article underscores that knowledge storage systems play a pivotal role in supporting social settings for effective knowledge-sharing practices. Second, KM technologies, such as databases, are essential tools that facilitate the access, sharing, storage, and analysis of organizational knowledge (Teece, 1998).

Firms' knowledge management practices (KMPs) and their associated structures are often linked to inter-organizational learning (IOL), thereby enabling businesses to nurture their competitive advantage. Organizations are becoming more interconnected through strategic alliances, partnerships, and collaborations (Rehman et al., 2023). Specifically, organizations’ KMP are detailed to collect, organize and share valuable knowledge, thereby supporting and boosting their learning activities (Tiwana, 2000). On the other hand, IOL, when appropriately integrated with a knowledge acquisition culture, facilitates the management of organizational changes through proactive actions (Castaneda et al., 2018). Nonetheless, a limited number of empirical studies suggest that businesses internal KMP supports innovation and fosters the elaboration of innovative solutions to address organizational challenges (Lee et al., 2013; Nesta & Saviotti, 2005).

Scholars conceptualize innovation as the acquisition of ideas and/or behaviors that are novel to a given entity, and it can be either disruptive or incremental (Harkema, 2003). Chiefly, innovation encompasses new technologies, products, and services (Rehman et al., 2022; Bresciani et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2023). Furthermore, innovation speed refers to an organization’s capability to respond to customer demands rapidly and compete in the marketplace by accelerating the processes of idea generation, development, and implementation of new products, services, and procedures faster than their key competitors (Aslam et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2016). Moreover, innovation speed refers to the organization’s ability to quickly generate novel ideas, new product launching, launch new product, and solve problems more efficiently than key competitors (Liao et al., 2010). Henceforth, in light of the above detailed academic writings, KMP plays a vital role in developing and enhancing firms’ OA, IOL, and innovation speed, thereby supporting organizations ability to respond to uncertain market conditions and benefit from emerging opportunities to attain or enhance their competitive advantage. Nevertheless, implementing KMP is not feasible without risk-taking behavior; firms need to foster a culture of risk tolerance to nurture the exploration of novel and creative solutions to address potential challenges (Qian et al., 2023). Therefore, businesses’ risk-taking attitudes reflect their organizational support to risk and control behaviors (Smith et al., 2005). However, the academic literature focusing on the foregoing issues lacks quantitative studies that seek to clarify these relationships and propositions. Furthermore, the limited number of empirical quantitative studies in the literature focus on Western countries therefore scholars might seek to evaluate the above-detailed interconnections within developing countries (Rehman et al., 2023). Additionally, scholarly writings require researchers to apply different theoretical frameworks to explore further and clarify the above-mentioned connections.

The gap in this research is the paucity of empirical work investigating the relationship between Knowledge Management Practices (KMP), Organizational Agility (OA), Inter-Organizational Learning (IOL), and Innovation Speed in the setting of companies working in dynamic and knowledge-intensive environments, especially in emerging economies such as Pakistan. At the same time, existing research has focused on single factors such as KMP (Broccardo et al., 2025) and IOL (Zgrzywa-Ziemak et al., 2025). Few studies examine how these factors interact. This discrepancy is especially pertinent in explaining how KMP can enhance OA through the mediation of IOL, and how the speed of innovation is the key to this connection. Past research has indicated the positive influence of KMP on innovation and flexibility (Riaz et al., 2023). Still, little research has extensively analyzed the function of IOL as a mediator between KMP and OA (Kale et al., 2000). In addition, although organizational agility and risk-taking are typically correlated, empirical studies on the role of risk-taking tolerance as a moderator of the KMP-OA relationship are rare. This current research fills such voids by introducing risk-taking tolerance as a moderator and exploring how it influences IOL and OA. Additionally, the conceptual frameworks employed by this research, including the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Knowledge-Based View (KBV), are established (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1996). However, synthesizing these frameworks with an emphasis on inter-organizational learning and innovation speed has not been extensively researched. By linking these factors, this study contributes to existing academic research by offering a more comprehensive perspective on how KMP can foster organizational agility within companies that seek to innovate within dynamic settings.

Therefore, considering the above-developed research gaps, this article seeks to contribute to the academic discourse surrounding OA, KMP and its pillars (namely culture, structure, and technology), IOL, innovation speed, and firms’ risk-taking tolerance. Specifically, this empirical research encompasses all key variables related to the aforementioned notions and aim to investigate their interconnecting relationships. First, this manuscript seeks to examine the relationship between KMP and OA. Second, to clarify the impact of IOL and innovation speed, this study examines their mediating effect on the relationship between KMP and OA. Finally, this body of literature aims to investigate whether risk-taking tolerance significantly moderates IOL, innovation speed, and OA.

Our empirical research study includes all key variables of organizational agility, KMP, IOL, innovation speed, and risk-taking tolerance attitude in a single current study in light of RBV and knowledge-based view (KBV) which were previously ignored and not examined by many researchers (Castaneda et al., 2018; Claver‐Cortés et al., 2007; Darvishmotevali et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2016). Furthermore, this study tests the mediating impact of IOL and innovation speed. Additionally, risk-taking tolerance is examined as a moderating factor in the relationship between organizational learning and innovation speed with organizational agility. This study sample comprises observations gathered from industries located in Lahore, Pakistan, due to their industrial relevance to the country's economic wealth. Moreover, the article focuses on the foregoing contextual focus due to the lack of empirical evidence from developing nations (Rehman et al., 2022; Rezaei et al., 2021). The authors employed a purposeful sampling technique, and 294 questionnaire responses were included in the analysis. Junior and senior managers were the respondents of this manuscript questionnaire. The authors employed the PLS-SEM method to analyze the obtained observations, as it is deemed effective for mediation analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2004) and it is preferable to OLS when samples size are small to address multicollinearity issues and missing values (Rehman et al., 2023). The obtained results are the following: I) KMP has a significant and positive relationship with OA, IOL, and firms’ innovation speed; II) there exists a positive and significant relationship between IOL and OA; III) the relationship between KMP and OA is significantly influenced by IOL; IV) the rate of innovation plays a significant role in the relationship between KMP and OA; V) there exists a positive correlation between organizations’ risk-taking tolerance and OA; VI) higher risk-taking tolerance enhances the connection between IOL and OA and; VII) no significant relationship was found between firms’ risk-taking willingness and the speed of innovation or OA.

The present body of literature carries several theoretical and practical implications in light of the above-reported results. First, the manuscript contributes to the academic discourse surrounding the foregoing notions and applies both the resource- and knowledge-based views. Second, it clarifies the relationships connecting the above-detailed notions, thus providing interesting insight to practitioners and managers. Third, it explores a relevant and novel geographical context, expanding scholarly literature. Finally, it offers promising new avenues for research to further explore and conceptualize the proposed relationships.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 contains the theoretical underpinnings, frameworks, and hypotheses development. Section 3 outlines the sample and methodological approach employed, while Section 4 presents the findings obtained. Finally, Section 5 details this research's discussion, concluding remarks, and implications.

Theoretical background and hypotheses developmentTheoretical framework: resource-based- and knowledge-based-viewDrawing on the RBV and KBV, this manuscript examines the strategic resources and intellectual capabilities that support IOL and innovation speed, ultimately influencing OA, with risk-taking tolerance serving as a moderating factor (Alhosani & Ahmad, 2024). The RBV posits that the effective allocation and utilization of resources and capabilities enhance innovation processes and improve overall organizational performance (Barney, 1991), thereby increasing a firm's competitive advantage over its rivals. Additionally, intangible and intellectual resources (Alhosani & Ahmad, 2024), such as KMP, create competitive advantages that are challenging for competitors to replicate (Hitt et al., 2006). The primary aim of organizations is to align and leverage all resources and capabilities to develop superior products and services for their customers, outperforming their competitors (Hitt et al., 2016). Henceforth, the RBV emphasizes valuing knowledge practices and aligning them with organizational processes and capabilities to enhance performance (Teece et al., 1997). This alignment impacts IOL, innovation, and agility (Christofi et al., 2024). Indeed, agile firms possess capabilities that allow them to quickly and proactively respond to business challenges by identifying innovative solutions and exploring emerging market opportunities. Furthermore, OA equips firms with the ability to act in anticipation of change rather than reacting after an event occurs. This enables them to manage uncertainty and market volatility, seizing emerging opportunities (Madhok & Marques, 2014). OA is rooted in two primary approaches: a proactive strategy, known as organizational flexibility, and a reactive strategy, referred to as organizational adaptability (Sherehiy et al., 2007).

Furthermore, the KBV extends the RBV by proposing that organizations can achieve a competitive advantage by strategically using their KMP. According to KBV, knowledge is a unique, dynamic strategic resource that evolves continuously through the generation and utilization of knowledge (Spender, 1996). Charbonnier-Voirin (2011) describes OA as an intentional, adaptive response that reflects an organization's ability to navigate unpredictable environments and capitalize on emerging opportunities through ongoing learning and innovation. Overby et al. (2006) argue that agile organizations can sense and respond effectively to market threats and opportunities. Nonetheless, to enhance this capacity, organizations need to strengthen the connection between managers and their working environment, thereby fostering knowledge-driven conversations, a collaborative culture, and faster innovation all of which are enabled by new technologies. Maintaining a competitive advantage requires firms to adapt to internal and external changes, which OA facilitates (Ulrich & Yeung, 2019).

Fundamentally, in light of the current global competition intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding OA has become even more critical for theoretical and practical insights since businesses can adjust their practices, culture, and strategies to remain and nurture their resiliency.

Knowledge management practicesManagement has increasingly emphasized the importance of KM in organizations, as it is crucial for both a firm’s survival and achieving a competitive advantage (Rehman et al., 2022). In a competitive environment, companies must focus on specialized, up-to-date knowledge to develop the capabilities necessary for gaining market share by offering high-quality products and services (Haider & Kayani, 2020). Both practitioners and academics consider KM essential for an organization's success and sustainability (Migdadi, 2020). Indeed, some studies have demonstrated that KM is pivotal for measuring organizational performance (Ferraris et al., 2017, 2018). KM capabilities are crucial in fostering organizational agility, enabling firms to respond promptly to market changes (Christofi et al., 2024; Hashem et al., 2024; Rafi et al., 2021). The literature suggests that agile organizations are adept at identifying, accumulating, and deploying resources at the right time, for the right people, and in the right place (Pereira et al., 2019). Knowledge enables organizations to anticipate changes in customer needs, manufacturing capacities, competition, materials, and market demand, whether sourced internally or externally. KM capabilities encourage firms to take initiatives, manage risks, and implement innovative strategies to adapt to volatile conditions (Hashem et al., 2024; Revilla et al., 2010). However, some scholars argue that KM may not have a direct influence on organizational performance (Wahda, 2017), suggesting that the relationship between KM and performance remains inconclusive and requires further investigation.

KM capabilities have been shown to significantly influence organizational learning in the Saudi food industry (Attia & Eldin, 2018). Indeed, KM is a robust infrastructure and a key enabler of the organizational learning process. While several studies have explored the link between KM and organizational learning (Al-Omoush et al., 2024; Nafei, 2014), this empirical investigation aims to examine IOL through various KM practices, such as -culture, -technology, and -structure. The KBV theoretical framework emphasizes the crucial role of KM in fostering innovation within firms (Nonaka & Toyama, 2005). Additionally, research has shown that KM significantly contributes to innovation by enabling the creation of new knowledge-based products which offer substantial additional value (Mata et al., 2024). Further, KM processes have been found to significantly enhance innovation capabilities within Jordanian firms (Migdadi, 2020). Therefore, considering the above detailed empirical evidence and theoretical underpinnings, the authors propose the following hypotheses:

H1 KMP are positively related to organizational agility

H2 KMP are positively related to inter-organizational learning

H3 KMP are positively related to innovation speed

Practitioners and academics often focus on IOL and its impact on improving a firm’s performance (Rehman et al., 2023). The importance of IOL has been growing rapidly (Al-Omoush et al., 2024; Mokhtarzadeh et al., 2021; Rehman et al., 2023). Indeed, IOL emphasizes the development and transfer of knowledge within and across organizations (Kohtamäki & Partanen, 2016). Organizations can derive significant benefits from engaging in IOL. Several researchers have strongly focused on the processes and mechanisms that enable this type of learning (Rajala, 2018). Some scholars have identified IOL as a particularly relevant and emerging topic, garnering increasing attention in academic circles (Kohtamäki & Partanen, 2016).

Furthermore, an organization's success typically depends on its ability to continuously differentiate its services and products from those of its key competitors (Chen & Huang, 2009). To maintain this distinction, organizations must prioritize ongoing innovation and continuous improvement. Innovation speed, therefore, refers to an organization’s ability to generate new ideas, launch new products, develop new processes, and solve problems more quickly than its main competitors (Aslam et al., 2024; Liao et al., 2010). Indeed, both RBV and KBV emphasize the importance of innovation as a key determinant of an organization's success (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1996). Several researchers have studied the role of innovation in driving firms' performance (Khan et al., 2019) and gaining a competitive advantage (Mata et al., 2024; Rehman et al., 2022). However, less attention has been given to examining how innovation speed contributes to OA (Aslam et al., 2024; Shan et al., 2016). Henceforth, considering the above detailed scholarly writings and theoretical frameworks, the authors formulate the below detailed hypotheses:

H4 Inter-organizational learning is positively related to organizational agility

H5 Innovation speed is positively related to organizational agility

Agile organizations are adept at identifying, accumulating, and deploying resources efficiently, thus delivering the right quantity at the right time, to the right people, and in the right place (Pereira et al., 2019). KM capabilities are regarded as significant predictors of OA (Rafi et al., 2021; Shehzad et al., 2024). However, some studies suggest that KM does not directly measure organizational performance (Wahda, 2017). This relationship remains inconclusive and warrants further exploration. The KBV and RBV suggest that organizational capabilities can enhance KM practices, OA, firm success, and competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1996).

This study introduces IOL and innovation speed as mediating variables between KMP and OA. The rationale for including these mediators is grounded in the KBV and RBV frameworks, which posit that organizational capabilities, such as IOL and innovation speed, play a crucial role in linking organizational resources (such as KMP) with agility (Christofi et al., 2024; Mata et al., 2024). Therefore, the authors develop the following hypotheses:

H6 Inter-organizational learning mediates between KMP and organizational agility

H7 Innovation speed mediates between KMP and organizational agility

Organizations that embrace risk-taking tend to foster knowledge management behaviors that emphasize both external environmental scanning and internal knowledge sharing (Choo, 2013). Businesses with a high risk-taking tolerance possess external KM capabilities that enable them to stay updated with modern trends and IT developments, enabling them to recognize opportunities and cultivate entrepreneurial behaviors. At the same time, these organizations strengthen their internal KM practices and capabilities, helping them to identify internal opportunities, innovate, and enhance OA (Choo, 2013). Consequently, companies with a high tolerance for risk tend to promote a KM culture that encourages learning through experimentation and diverse experiences (Shehzad et al., 2024; Smith et al., 2005). Without a risk-tolerant attitude, organizations may hesitate to encourage employees to propose creative solutions for addressing urgent problems (Qian et al., 2023).

Furthermore, organizations that encourage risk-taking motivate their employees to enhance their knowledge, explore innovative ideas, and create new products for emerging markets by leveraging internal and external knowledge sources (Choo, 2013). Consequently, these companies tend to embrace a certain level of disorder in pursuing novel concepts (Smith et al., 2005). The concept of discovery-driven innovation emerges in environments with a high tolerance for risk, fostering a culture where experimentation and learning are integral to developing business models (McGrath, 2010). Given these considerations, we expect that varying risk tolerance levels within organizations will influence how they manage and ascribe value to their knowledge. To mitigate vulnerabilities and enhance decision-making, firms must proactively identify new opportunities and challenges within and beyond the organization (Sanchez & Ricart, 2010). Prior research has often overlooked the moderating role of risk-taking tolerance between IOL, innovation speed, and organizational agility (Mata et al., 2024). Therefore, this study aims to address that gap by exploring the impact of risk-taking tolerance on these dynamics, thereby, the authors developed the following research hypotheses.

H8 RTT is positively related to organizational agility

H9 RTT is significantly moderate inter-organizational learning and organizational agility

H10 RTT significantly moderates between innovation speed and organizational agility

Fundamentally, the following Fig. 1 graphically depicts the above-detailed relationships and hypotheses in an attempt to clarify further the content, aim, and scope of this study.

MethodologyQuestionnaire constructionThe developed questionnaire contains constructs and items attributable to five variables: KMP, OA, IOL, innovation speed, and risk-taking tolerance. As detailed below, the authors gathered all constructs and their associated items from previous scholarly writings. First, KMP is measured through three core dimensions: culture (4 items), technology (3 items), and structure (4 items) (Gold et al., 2001). Second, OA is constructed of six items gathered from Lu and Ramamurthy (2011) research. Third, IOL consists of six items that were gathered and adapted from Janowicz-Panjaitan and Noorderhaven (2008) and Schilke (2014). Fourth, the innovation speed construct comprises of five items collected from the Liao et al. (2010) publication. Finally, risk tolerance is composed of four times (Tellis et al., 2009; Herzog & Leker, 2010). The full questionnaire is attached in the appendix.

Population and samplingThe authors wanted to focus on the geographical context of Lahore, Pakistan, to bridge the following contextual gap. Indeed, while most academic discourse surrounding KMP focuses on Western contexts (Ferraris et al., 2021; Dezi et al., 2019, 2018), a limited amount of researchers have gathered and analyzed empirical data from developing and Eastern countries such as Pakistan (Rehman et al., 2022; Rezaei et al., 2021). Specifically, the authors focused on Lahore because it is Pakistan's second largest city and industrial hotspot, with over 9.000 industrial firms (Rehman et al., 2022). Moreover, several previous studies have collected data from Lahore, Pakistan, while studying similar constructs (Rehman et al., 2022; Riaz & Ali, 2023b). Therefore, details concerning organizations were gathered from the Lahore Chamber of Commerce. The authors found it relevant to reach out to firms across various industries to gather empirical insights that could provide a comprehensive, cross-sectional analysis. Henceforth, the selected sample comprises firms operating in various sectors, including chemical, automotive, health and pharmaceutical, polymers, food, and textiles.

To test the validity of our questionnaire, the authors solicited feedback from both expert academics and professionals. The authors employed the foregoing feedback further to refine the style and structure of the questionnaire. Thereafter, the authors distributed the final draft of the questionnaire to 1000 junior and senior managers operating in the aforementioned entities. The final respondents were 299. Nonetheless, five responses had to be discarded due to misleading values. Therefore, the final sample comprises 294 respondents. Specifically, the sample is structured as follows: 93.86 respondents were male. Second, most respondents were senior managers (76.53 %), while the remaining were junior managers. Third, 24.15 % of respondents hold a bachelor’s degree, 68.71 % a master’s degree, and 4.08 % a M.Phil. Fourth, the companies’ industrial distribution is as follows: 39.80 % textile, 9.52 % chemical, 6.46 %leather and tanneries, 11.56 % plastic and PVC, 6.80 % food, 9.52 % medicine, and 16.34 % automotive. Finally, 23.47 % of entities have fewer than 100 employees, 47.96 % of organizations have between 101 and 500 employees, 23.12 % of firms have between 500 and 1000 employees, and the remaining organizations employ >1000 people.

Common method bias (CMB)Our study collects data from junior and senior managers simultaneously, addressing both exogenous and endogenous constructs through the detailed, structured questionnaire outlined above. Consequently, a few researchers have confirmed that Common Method Bias (CMB) issues can arise, potentially affecting the validity of a study’s data (Rehman et al., 2022). Indeed, in behavioral studies, CMB often presents a significant concern since there are serious issues in self-reported surveys (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). Various techniques, both procedural and statistical, can be employed to minimize the impact of CMB. From a procedural perspective, researchers can reassure respondents that their data will not be shared with third parties without their consent. The questionnaire should be written in simple and clear language. The reverse code approach was not followed because the questionnaire items were not a mixture of positive and negative statements. The authors tested for full collinearity, and the obtained value is below 3.3. Harman's single-factor test explains 37.123 % of the total variance, which is below the 50 % threshold (Bresciani et al., 2024; Cabrilo et al., 2024; Li et al., 2022). Unmeasured Latent Method Construct (ULMC) was used to check CMB. The R2 values of the measured and unmeasured latent variable were compared, and the difference in R2 values was below 7 % (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). Henceforth, no significant CMB issue is present.

Model estimationWe employed the PLS-SEM method to investigate the research framework detailed in this article. The foregoing methodological approach has been deemed appropriate for various reasons. First, according to the literature, PLS-SEM is an effective methodological approach for conducting mediating analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Second, PLS results are preferable to OLS when dealing with small sample sizes, multicollinearity issues, and missing values (Rehman et al., 2023). PLS-SEM is widely accepted and used by several researchers in different areas (Elrayah & Tufail, 2024; Ghaleb & Juhari, 2024; Bhatti & Yacob, 2024; Wiroonratch et al., 2024). The research framework encompasses KMP, IOL, speed of innovation, risk-taking tolerance, and OA. Specifically, the employed PLS-SEM consists of a measurement and structural models. Therefore, Table 1 shows that the minimum loading is 0.595, and the maximum is 0.910, which exceeds 0.50 (Hair et al., 2014). The composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach's alpha values for each first-order latent variable (LV) exceed 0.70, indicating no internal consistency concerns. Convergent validity refers to assessing whether the items of variables accurately measure the same underlying construct. Convergent validity is assessed by calculating the average variance extracted (AVE), which should exceed 0.50. To improve the results for CR and AVE, the researchers should exclude items with loadings below 0.50, as suggested by Bhatti and Rehman (2020). Table 1 indicates that the results of convergent validity are satisfactory. We employed WarpPLS 7.0 software to compute complete collinearity, and Table 1 demonstrates the absence of multicollinearity concerns. Fig. 2 depicts the measurement model in first order.

Convergent validity.

Source: Authors own work.

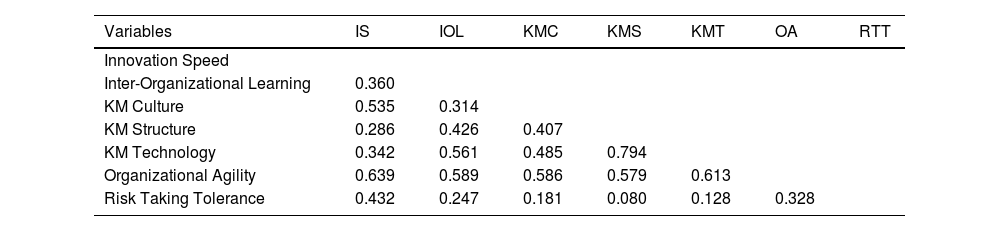

Discriminant validity refers to how every variable varies statistically from another variable. In earlier times, traditional metrics were followed to examine discriminant validity, as proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981). HTMT is considered a suitable method where loadings have little difference. The HTMT value is 0.90 for variables conceptually different and 0.85 for conceptually same. Table 2 highlights that there is no issue of discriminant validity at first-order. Fig. 3 portrays the measurement model in second order.

Discriminant validity for first-order (HTMT).

Source: Authors own work.

Thereafter, for the second-order variables, run the measurement model. In this study, only KMP is a second-order construct with three dimensions: culture, structure, and technology. All the variables of the research model are reflective. Thus, the measurement model was investigated using one second-order variable, i.e., KMP, and four first-order constructs: inter-organizational learning, innovation speed, risk-taking tolerance, and organizational agility. Our research model is reflective-reflective. Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate that all the criteria of the factor loading, AVE, CR, full-collinearity, and discriminant validity are fulfilled in the second order.

Convergent validity.

Source: Authors own work.

This study encompasses six direct hypotheses, two mediating hypotheses, and two moderating hypotheses. Fig. 4 depicts the structural model. KM practices have a significant positive relationship with organizational agility (p = 0.000, and t = 6.872), inter-organizational learning (p = 0.000, and t = 11.670), and innovation speed (p = 0.000, and t = 11.399), thereby confirming hypotheses H1, H2, and H3. The study found a positive relationship between inter-organizational learning (p = 0.000, and t = 4.975) and innovation speed (p = 0.000, and t = 5.568) with organizational agility. This supports hypotheses H4 and H5. The relationship between KM practices and organizational agility was significantly influenced by inter-organizational learning (p = 0.000, and t = 4.835), supporting hypothesis H6. In addition, the rate of innovation plays a significant role in the relationship between KM practices and organizational agility (p = 0.000, and t = 5.341), thus supporting hypothesis H7. The study found a positive correlation between risk-taking tolerance and organizational agility (p = 0.026, and t = 2.412), which supports hypothesis H8. The study found that a higher tolerance for taking risks enhances the connection between inter-organizational learning and organizational agility. The statistical analysis showed a significant positive relationship, with a beta coefficient of 0.131, a p-value of 0.002, and a t-value of 3.477. This finding supports Hypothesis H9. Ultimately, there is no significant relationship between the willingness to take risks, innovation speed, and organizational agility. The statistical analysis shows that the beta coefficient (β) is 0.026, the p-value is 0.583, and the t-value is 0.566. Therefore, Hypothesis H10 is not supported. Table 5 displays the complete set of results. Fig. 5 illustrates that the level of willingness to take risks enhances the positive correlation between inter-organizational learning and organizational agility.

Hypotheses testing.

Source: Authors own work.

According to Cohen (1988), there are three levels of f2: small (f2≥0.02), medium (f2≥0.15), and higher effect (f2≥0.35). Table 5 highlights that inter-organizational learning and risk-taking tolerance have a small effect on organizational agility. At the same time, innovation speed and KMP have a medium effect on organizational agility. Finally, KMP has a medium effect on inter-organizational learning and innovation speed.

Two metrics are used to assess the predictive relevance of the model, namely R2 and Q2. According to Falk and Miller (1992), R2 should be at least 0.10. Table 3 shows that the R2 value for innovation speed, inter-organizational learning, and organizational agility are greater than 0.10. The second criterion is Q2, computed in SmartPLS using the blindfolding technique. The value of Q2 should be greater than zero (Geisser, 1974). Table 6 indicates that the Q2 values for innovation speed, inter-organizational learning, and organizational agility are greater than zero. Hence, both criteria were fulfilled, ensuring the predictive relevance of the model.

Discussion and concluding remarksIn this study, observations were gathered through a structured questionnaire focused on the following key variables: KMP, OA, IOL, innovation speed, and risk-taking tolerance. The employed constructs and items were gathered from academic literature and administered to junior and senior managers from a diverse sample of organizations located in Lahore, Pakistan, and operating in varying industry sectors. Specifically, the research sample was composed of 294 valid responses.

The adopted methodology consists of PLS-SEM for data analysis since it offers a robust approach suitable for handling smaller sample sizes and addressing multicollinearity issues. Furthermore, the authors employed Harman’s single-factor test and found no significant issues with CMB. The results indicated satisfactory convergent validity, composite reliability, and internal consistency for the selected variables analyzed.

This study aims to contribute to both the KBV and RBV theories. Specifically, according to the KBV, dynamic and intangible resources such as KMP, IOL, innovation speed, and risk-taking tolerance are key determinants of OA. Furthermore, the RBV posits that an organization's capabilities explain the link between its resources and its ability to sustain a competitive advantage over time. Our research develops a model that highlights the efficient use of KMP, IOL, innovation speed, and risk-taking tolerance as critical factors for enhancing organizational agility (Christofi et al., 2024).

KMP increases OA, thus corroborating the proposition concerning H1. Specifically, the obtained results concerning H1 support the academic literature, which postulate that organizations’ collaborative knowledge efforts enhance their OA (Al-Omoush et al., 2020; Rafi et al., 2021; Shehzad et al., 2024). Additionally, researchers have revealed that KM capabilities significantly improve entities’ OA (Motwani & Katatria, 2024; Rafi et al., 2021). In an attempt to contribute to the existing academic literature, this manuscript details KMP as internal KM capabilities, thereby underscoring the need for managers to focus on KMP in order to determine their OA potentially. For instance, firms that nurture a culture where workers are encouraged to interact and enhance their expertise are likely to experience a stronger relationship, as previously detailed in academic writings. Consequently, organizations should utilize new technologies to discover new knowledge (Nonaka & Toyama, 2005). Moreover, the obtained findings corroborate academic literature detailing how firms' structure enables the discovery of new knowledge (Pereira et al., 2019).

This manuscript corroborates the academic literature which details a positive link between KMP and IOL, thereby supporting the proposition to construct H2. Specifically, the obtained results further support the empirical insights presented by Attia and Eldin (2018), igniting the potential similarities between the Pakistani and Saudi Arabian samples. Fundamentally, managers seeking to nurture an IOL culture must direct their resources toward KMP initiatives. Furthermore, this manuscript corroborates scholarly insights that detail the positive and significant link between firms’ KMP and their innovation speed (Rehman et al., 2022) and supports H3. Fundamentally, KMP allows organizations to undertake higher-risk initiatives, pursue innovative strategies, and address potential challenges through innovative practices (Revilla et al., 2010). This article supports the academic literature which details a positive and significant relationship between IOL and firms’ OA, thereby corroborating the proposition to establish H4. Indeed, this manuscript insights do align further corroborate the notions and results presented by Bahrami et al. (2016), thus suggesting managers need to acquire and absorb knowledge from a multitude of stakeholders to increase their organizations’ OA (Rafi et al., 2021; Wahda, 2017). The obtained results support the previously developed H5; thereby, scholarly writings supporting the above-mentioned relationship find additional uphold in this body of work. Fundamentally, this article corroborates the positive and significant link between firms’ innovation speed and their OA (Ravichandran, 2018). Additionally, this manuscript insights detail no significant differences between the obtained results and previous empirical evidence gathered from Western countries. IOL and innovation speed mediate the relationship between KMP and OA, while risk taking tolerance has a positive influence on OA. Thus, it supported H6 and H7. Specifically, similarly to the insights of Grant (1996), organizational capabilities (detailed as inter-organizational learning and innovation speed) explain the knowledge resources and organizational performance of firms (Al-Omoush et al., 2024). The findings obtained are also novel in scholarly writings, as less attention has been paid to exploring the indirect effect of KMP and OA on the existence of IOL and innovation speed. Therefore, the obtained results contribute significantly to addressing the research gaps previously identified in Sections 1 and 2 of this article.

Finally, this manuscript supports the academic conceptualization of organizations’ risk-taking positive effect on firms’ OA (Qian et al., 2023; Sanchez & Ricart, 2010; Smith et al., 2005) and supports H8. Fundamentally, OA through risk-taking tolerance is often overlooked. Thus, this body of work offers novel insights, thereby addressing the gaps in the research that have been identified. Additionally, the findings of this manuscript strongly indicate that risk-taking tolerance significantly bolsters both IOL and OA. Hence, H9 is accepted. Nevertheless, risk-taking tolerance does not moderate the relationship between firms’ innovation speed and OA. Thus, H10 is not supported. This study shows that innovation speed directly determines OA, but risk-taking tolerance does not moderate this relationship. This may be due to context; results vary when the same study is conducted in a different context. Prior researchers have often overlooked the moderating role of risk-taking tolerance between innovation speed and OA (Mata et al., 2024). The speed of innovation and OA are more driven by internal variables such as the efficiency of decision-making and allocation of resources, rather than risk-taking (Teece, 2007). In highly competitive industries, for example, companies will tend to concentrate on incremental innovation and process enhancements that need flexibility but not high levels of risk-taking (Zahra & George, 2002). In addition, organisational agility tends to rely on a firm's ability to adapt quickly, which can be achieved through operational flexibility rather than a risk-taking predisposition (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997; Riaz & Ali, 2023a). Therefore, risk-taking tolerance does not always play a critical moderating role in the innovation speed-OA relationship.

Theoretical implicationsThe academic literature has several theoretical implications and further advances the scholarly discourse surrounding the concepts detailed in Section 2. First, the obtained insights further explore and contribute to the scholarly writings concerning KMP, IOL, innovation speed, risk-taking tolerance, and OA. Specifically, this article builds upon the work of Rehman et al. (2022), thereby revealing that KM and intellectual capital directly and indirectly impact the competitive advantage of Pakistani manufacturing firms’. Second, this study explores KMP, IOL, innovation speed, and risk-taking tolerance through the KBV theory, thus broadening our understanding of OA (Grant, 1996). Indeed, this body of work explores the above-detailed notions through KBV- and RBV-theory, postulating a novel approach to future research endeavors. Third, this manuscript extends the academic discourse by determining businesses’ OA through collaborative knowledge creation(Al-Omoush et al., 2020). Moreover, the findings underscore the necessity of for nurturing organizations’ OA (Hashem et al., 2024; Rafi et al., 2021). Fourth, the authors expand the literature by exploring the appropriate theoretical frameworks to determine firms’ competitive advantage through KM practices (Rehman et al., 2022). Sixth, this body of literature addresses the lack of research concerning the possibility of determining entities’ OA through KMP as knowledge is detailed to be one of the most relevant resources for organizations’ success or failure (Ooi, 2014; Rehman et al., 2023). Finally, the findings contribute to the academic literature by presenting empirical evidence detailing risk-taking tolerance as a moderator between IOL, innovation speed, and OA (Hock-Doepgen et al., 2021).

Managerial and social implicationsFirst, the research highlights that KMP is part of promoting OA. Managers should focus on establishing a knowledge-based culture in their organizations through knowledge sharing, collaboration, and learning. This can be achieved by enforcing the use of knowledge management systems, including collaborative websites and information-sharing portals, to ensure that crucial information reaches all employees. This will facilitate quicker decision-making and a faster organizational response to external developments, leading to greater adaptability to changing market environments. Socially, encouraging knowledge sharing in organizations also fosters the development of social capital in industries and communities, as companies collaborate to exchange insights and best practices, ultimately benefiting local labor markets and skill formation. Second, the report calls for emphasis on the indispensable role of IOL in spearheading OA. Managers should deliberately pursue external partnerships, collaborations, and alliances to promote organizational learning.

By forging robust networks with industry rivals, research centers, and even competitors, organizations can access various sources of knowledge and accelerate their innovation processes. The sharing of best practices and innovative ideas resulting from these collaborations will enable firms to innovate at a faster pace and enhance their competitive advantage, ultimately increasing their agility in responding to market shifts. This cooperation has broader implications for society, including the creation of employment opportunities and the spillover of innovative solutions capable of solving social problems such as sustainability and health. Third, the research indicates that tolerance to risk-taking is a significant determinant of OA. Higher-risk tolerance organizations can create a more innovative and agile organization. Managers can promote a culture that supports responsible risk-taking, experimentation, and innovation. This can be achieved by giving the employees the authority to pursue new ideas and projects without fear of failure, thereby promoting creativity and breakthrough innovations. An adaptive decision-making system that facilitates experimentation will enable organizations to take advantage of new opportunities, becoming more resilient and responsive in ambiguous settings. Socially, encouraging ethical risk-taking can lead to innovations with beneficial effects on society, including the development of environmentally friendly products or technologies that promote environmental sustainability and address critical social issues. Finally, the coordination of KMP, IOL, and innovation speed in strategy formulation is crucial for achieving lasting organizational success. Managers must appreciate the interdependence of the variables and integrate them into the company's strategy. Through the creation of cross-functional teams, inter-organizational learning, and innovation pipelines, organizations can hasten the evolution of new offerings. These strategic plans, in addition to enhancing operational effectiveness, will help create a more agile and innovative organization with the ability to sustain a competitive advantage in an increasingly dynamic market. At the societal level, responsible innovation by organizations has the potential to enhance overall social welfare by addressing issues such as poverty, health, and environmental concerns, thereby benefiting both the firm and society.

Limitations and future research avenuesThis research is informative; however, it also has several limitations that future studies can address. First, the cross-sectional design restricts the potential to draw conclusions regarding long-term causal relationships, and thus, longitudinal studies may provide a clearer picture of how KMP, IOL, innovation speed, and risk-taking tolerance affect OA in the long term. Second, the research's narrow definitions of KMP, IOL, innovation speed, risk-taking tolerance, and OA might be broadened or clarified to analyze their long-term impact on business performance. Third, as IOL and innovation speed act as mediators, future research may investigate other constructs, e.g., management control systems, which could also contribute to the KMP-OA relationship. Other moderating factors such as environmental competitiveness, organizational ambidexterity, and uncertainty may also be investigated to provide a more comprehensive picture of OA. The inclusion of sustainability factors, including the effect of KMP on environmental performance, would make the findings richer (Kraus et al., 2020; Réhman et al., 2021). In addition, examining the harmful effects of knowledge hiding on OA and investigating geographical and contextual variations through comparative country studies may aid in understanding possible differences in findings. Finally, using a mixed-methods approach would facilitate more in-depth insights into KMP and OA dynamics. Resolving these limitations through future studies could significantly enhance the understanding of knowledge management and organizational agility, particularly in emerging markets.

CRediT authorship contribution statementShafique Ur Rehman: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Stefano Bresciani: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization. Daniele Giordino: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Amir A. Abdulmuhsin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Knowledge Management PracticesGold et al. (2001).

Knowledge Management Culture

- 1.

In my organization employees are valued for their individual expertise.

- 2.

In my organization employees are encouraged to ask others for assistance when needed.

- 3.

In my organization employees are encouraged to interact with other groups.

- 4.

In my organization employees are encouraged to discuss their work with people in other workgroups.

Knowledge management technology

- 1.

My organization uses technology that allows it to search for new knowledge.

- 2.

My organization uses technology that allows it to retrieve and use knowledge about its products and processes.

- 3.

My organization uses technology that allows it to retrieve and use knowledge about its markets and competition.

Knowledge management structure

- 1.

My organization structure facilitates the discovery of new knowledge.

- 2.

My organization structure facilitates the creation of new knowledge.

- 3.

My organization designs processes to facilitate knowledge exchange across functional boundaries.

- 4.

My organization structure facilitates the transfer of new knowledge across structural boundaries.

Innovation SpeedLiao et al. (2010).

- 1.

Our organization is quick in coming up with novel ideas as compared to key competitors.

- 2.

Our organization is quick in new product launching as compared to key competitors.

- 3.

Our organization is quick in new product development as compared to key competitors.

- 4.

Our organization is quick in new processes as compared to key competitors.

- 5.

Our organization is quick in problem solving as compared to key competitors.

Risk Taking Tolerance (Herzog & Leker, 2010; Tellis et al., 2009).

- 1.

Our company places high value on taking risks, even if there are occasional mistakes.

- 2.

In our company, risky activities are commonplace.

- 3.

Relative to other companies, we tend to favor higher-risk, higher return decisions.

- 4.

Managers in our company rarely make risky decisions.

Inter-organizational Learning (Janowicz-Panjaitan & Noorderhaven, 2008; Schilke, 2014)

- 1.

We acquire and absorb knowledge from our partners in the course of the collaboration.

- 2.

We have adequate routines to analyze the knowledge obtained from our partners.

- 3.

We can successfully integrate our existing knowledge base with new knowledge acquired from our partners.

- 4.

We have the capability to learn very things from our partners.

- 5.

What we have learned from the partners we use in our independent projects.

- 6.

What we have learned from partners helped us improve our performance.

Organizational AgilityLu and Ramamurthy (2011).

- 1.

We have the ability to rapidly respond to customers’ needs

- 2.

We have the ability to rapidly adapt production to demand fluctuations

- 3.

We have the ability to rapidly cope with problems from suppliers

- 4.

We rapidly implement decisions to face market changes

- 5.

We continuously search for forms to reinvent or redesign our organization

- 6.

We see market changes as opportunities for rapid capitalization