Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), with its potential to autonomously generate new content in the form of text, video, audio and code, holds disruptive potential to revolutionize knowledge management (KM) processes. An enormous number of studies have been published in recent years on the application of GenAI and this number is expected to increase further. Nevertheless, there are relatively few studies that systematize this research domain, and they are scarce from a KM perspective. For this reason, this study intends to bridge the current gap by offering both qualitative and quantitative insights in this research field using a bibliometric literature review, combining descriptive analysis with science mapping techniques, to analyse the impact GenAI has on KM processes. In particular, the aims of this paper are to provide a structured overview of how GenAI research contributes to the evolution of KM, to identify inconsistencies in the understanding of GenAI’s role in knowledge creation, and to propose directions for future theoretical and empirical research. In addition, our contribution proposes both the introduction of a new conceptual dimension, namely the machine dimension, which may extend traditional knowledge generation models, and a conceptual taxonomy for analysing GenAI readiness that is useful for managers and practitioners.

In today’s increasingly complex environment, knowledge constitutes a critical asset for organizations thanks to its capacity to foster innovation, competitiveness, and efficiency (Centobelli et al., 2018; Chaudhuri et al., 2021; Marques Júnior et al., 2020; Wu & Wang, 2006). However, the amount of information and the speed of its generation have been growing exponentially, making the ability to effectively manage this knowledge crucial in order to exploit new knowledge-related opportunities (Sivarajah et al., 2017). In response to these dynamics, knowledge management (KM) has emerged as a vital discipline, focusing on the systematic processes of capturing, developing, sharing, and effectively using organizational knowledge (Idrees et al., 2023; Chang Lee et al., 2005). This research field is gaining prominence because it embodies the best way to systematize the management of this flow of information to ensure organizations are ready to develop decision-making capabilities; it also fosters innovation by making the best use of knowledge resources (Ode & Ayavoo, 2020; Sun et al., 2022; Bharati et al., 2015). Within this context, generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) plays a revolutionary role.

Generative AI (GenAI)

GenAI refers to a subset of AI technologies capable of generating new content based on structures learned from training data (Dwivedi et al., 2023). This generation can include text, images, music, and code (Ray, 2023). Based on the above definition, it is clear that rather than presenting a new tool, GenAI could constitute a new methodology to enhance the creation, storage, and dissemination of knowledge, promising to revolutionize traditional KM practices by enabling more dynamic and adaptive knowledge processes (Del Giudice & Della Peruta, 2016). More specifically, it is significant that GenAI models rely on deep learning algorithms, which are complex networks capable of handling large datasets and performing various tasks (Goodfellow et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2024). These models automatically learn patterns and data structures from raw data, without relying on manually defined statistical features (Fu et al., 2023; Di Meglio et al., 2024; W. Wang et al., 2017). From a KM perspective, it is significant that GenAI can autonomously generate documents, design prototypes, simulate outcomes, and even predict future trends by analysing past and current data streams (Mao et al., 2016). Its ability to process and synthesize vast amounts of information rapidly and accurately can significantly enhance organizational knowledge bases and optimize the use of both internal and external sources of information (Cabrilo et al., 2024).

Emerging challenges in KM with GenAI

As GenAI becomes embedded in knowledge work, several challenges have emerged that must be addressed for its responsible and effective use in KM systems. These include the complex nature of algorithms, which leads to what is often referred to as the ‘black box’ problem (Brozek et al, 2023). Specifically, the decision-making process within AI systems is opaque and not easily understood by humans (Shwartz-Ziv & Tishby, 2017). This lack of transparency constitutes an issue for organizations seeking to enhance AI responsibly and transparently(Saura et al., 2024; Ghasemaghaei & Kordzadeh, 2024). As a result, there is a growing interest in explainable AI (XAI), which tries to make AI decisions more understandable to humans (Al-Busaidi et al., 2024; Barredo Arrieta et al., 2020). XAI involves developing methods and technologies that can clarify the way AI models make their decisions (Adadi & Berrada, 2018). From a KM perspective, this transparency is crucial because it ensures that the insights and knowledge generated by AI are trustworthy and can be audited, fostering greater confidence among stakeholders and facilitating more informed decision-making (Climent et al., 2024; Bedué & Fritzsche, 2022; Masood et al., 2023).

To understand the revolutionary potential of GenAI within organizations, it is essential to realize that this technology is potentially present even without being formally adopted in a structured manner. In fact, the term ‘shadow AI’ refers to situations in which AI tools are used unofficially in organizations without formal endorsement from decision-makers (Kwan, 2024). Employees may turn to AI solutions to enhance their productivity or solve complex problems, often bypassing traditional IT channels. From a KM perspective, shadow AI is both a challenge and an opportunity; it highlights the urgent need for formal governance frameworks to manage AI adoption but also demonstrates the inherent value employees see in AI tools to enhance their work processes (Kwan, 2024).

In essence, the integration of GenAI into KM is not merely the adoption of new technologies. Rather, it involves embracing a fundamental shift in how knowledge is generated. It raises questions about how machines process knowledge and, more specifically, how they create new knowledge. Such a revolution suggests that the generation of knowledge should be studied by analysing how human and artificial intelligence can cooperate to produce knowledge (Rives et al., 2021; Gupta et al., 2018; Merk et al., 2018), rather than looking only at how machines process information.

Research gap

Despite the increasing use of GenAI across many sectors (Chiu, 2023; Kanbach et al., 2024), its impact on KM processes, particularly in redefining how knowledge is created, validated and ultimately shared, remains underexplored. Specifically, while GenAI is widely studied regarding its technical and sectorial implications, there is currently no comprehensive review that examines its influence on KM frameworks, nor its potential to redefine knowledge creation itself.

Research aim and contribution

This study is intended to bridge this gap by offering both qualitative and quantitative insights for this research field through a bibliometric literature review, which combines descriptive analysis and science mapping techniques to analyse the impact that GenAI has on KM processes. In particular, the aims of this paper are to provide a structured overview of how GenAI research contributes to the evolution of KM, to identify inconsistencies in scholarly understanding of GenAI’s role in knowledge creation, and to propose directions for future theoretical and empirical research. In addition, our contribution offers both a conceptual foundation for integrating machine-generated knowledge into KM theory, to complement traditional knowledge generation models, and a conceptual taxonomy for analysing GenAI readiness for managers and practitioners to use.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: after this introduction, section 2 presents the review methodology adopted in this paper. Section 3 and section 4 provide and analyse our results. Section 3 specifically offers a descriptive analysis of our results while section 4 explores these results using science mapping methodology, along with the results of our article classification process. A deeper insight into our findings is presented in section 5. Finally, the relevance of this study is summarized in the conclusion in section 6.

Methods and materialsDespite widespread interest in GenAI across various fields, there is a relative scarcity of contributions attempting to systematize this growing body of knowledge from a KM perspective. For this reason, the aim of this article is to employ a bibliometric analysis that combines descriptive analysis and science mapping techniques (Noyons et al., 1999; Cobo et al., 2011) in order to contribute further insights to this field of research.

Indeed, bibliometric analysis is a robust and efficient method employed across many fields to methodically monitor patterns, characteristics, and trends in academic literature on a particular subject or topic (Gaviria-Marin et al., 2018; Dzhunushalieva & Teuber, 2024). It provides a comprehensive and structured overview of major and influential contributions by pertinent authors, significant publications, top journals, institutions, and countries (Gaviria-Marin et al., 2018). Compared to other review methodologies, a bibliometric approach enables authors to obtain both qualitative and quantitative insights into the subject at hand. While bibliometric analysis provides a clear overview of the relationship between different bibliometric objects through mathematical and statistical methods (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017; De Bellis, 2009), scientific mapping is essential if we are to identify different research themes in the domain, track research developments, and detect ongoing research gaps.

The methodology adopted in this review, as shown in Fig. 1, consists of four main steps:

- i.

Data acquisition. This provides further details regarding the academic database used and the reasons for keyword choices.

- ii.

Data pre-processing. This includes all the operations essential to prevent non-relevant articles from being included in the analysis.

- iii.

Results analysis. This is structured in two sections:

- a.

Descriptive analysis. Descriptive analysis is conducted with reference to the:

- a.

Chronological distribution of the papers

Geographical distribution of the papers

Distribution of the papers by subject area

Distribution of the papers across journals

Most productive authors

Most relevant contributions

- a.

Science mapping. Statistical and mathematical techniques are employed to analyse various aspects of a research field using a quantitative approach. The aim is to identify different patterns within the research field structure. This approach has been documented in different studies (De Bellis, 2009; Mora et al., 2019) and it provides a visual account of the bibliometric data collected through the use of complex networks, such as graphs and maps, in which elements can be interconnected according to specific criteria (Ding et al., 2001; Hashem et al., 2016), and also furnishes insights into the conceptual, intellectual, and social structure of specific research fields (Cobo et al., 2011). Specifically, these graphs are made of nodes, which represent different bibliographical elements to analyse – authors or countries, for instance – and edges, which represent the connections between the nodes, such as co-citation and co-occurrence. The most common methods employed to assess meaningful connections are co-citation analysis and co-occurrence analysis (He, 1999), which were both employed in this review. Then, after identifying five clusters through keyword co-occurrence analysis performed with VOSviewer software, these were qualitatively validated in order to verify the alignment of articles with the same theme. Next, through a discussion session amongst the authors, a title was selected for each cluster that would best represent the main themes. A subset of representative articles was selected for qualitative interpretation for each cluster, based on their centrality (keyword closeness centrality score), citation count and conceptual richness. This allowed us to identify deeper insights into the key themes and emerging issues as reflected in the literature, in line with bibliometric review standards (Mora et al., 2019).

- a.

- i.

Classification of articles. A semi-automated article classification procedure was implemented with the aim of classifying each individual article into the corresponding co-occurrence based thematic cluster. The transparent and replicable approach employed, as is extensively shown in Section 3.3, was based on both quantitative measures (closeness centrality scores) and qualitative steps (keyword refinement).

Data collection was performed using the Scopus academic database and included all articles available up to the end of the collection phase. In terms of keyword selection criteria, rather than using combinations of keywords that explicitly relate GenAI to the KM field, our search strategy employed only keywords related to GenAI. This was done to reduce the loss of information that could have been caused by articles that did not directly refer to KM but still contained information relevant to the aim of this study. Specifically, the research string we used was as follows: TITLE-ABS-KEY (‘generative artificial intelligence’ OR ‘GenAI’ OR ‘generative AI’ OR ‘GAI’). As mentioned earlier, the string was structured specifically to embrace all articles across various fields dealing with GenAI. No additional keywords were integrated, to prevent any loss of information and keep the research scope as broad as possible. In addition, the research technique we employed omitted technical terminology associated with the early phases of GenAI, indirectly filtering out papers that contained only technical insights. This filtering approach helped target the evolving nature of GenAI as it enters KM discourse and mainly included contributions on what can be considered to be the second wave of GenAI research, centred on the interpretive and organizational use of GenAI in real-world contexts, such as education, decision-making and knowledge management.

Moreover, there was no lower bound on the publication date of articles included and no restrictions were applied based on journal rankings or quartile classifications, as the goal was to capture the broadest possible landscape of GenAI research across disciplines. This decision was made to prevent the inadvertent exclusion of early-stage and interdisciplinary studies, which may be published in emerging or non-mainstream journals. This search yielded 3,258 items. Given the ongoing rapid increase in the number of articles published in this field, it is imperative to note that the collection phase was finalized on September 20th, 2024.

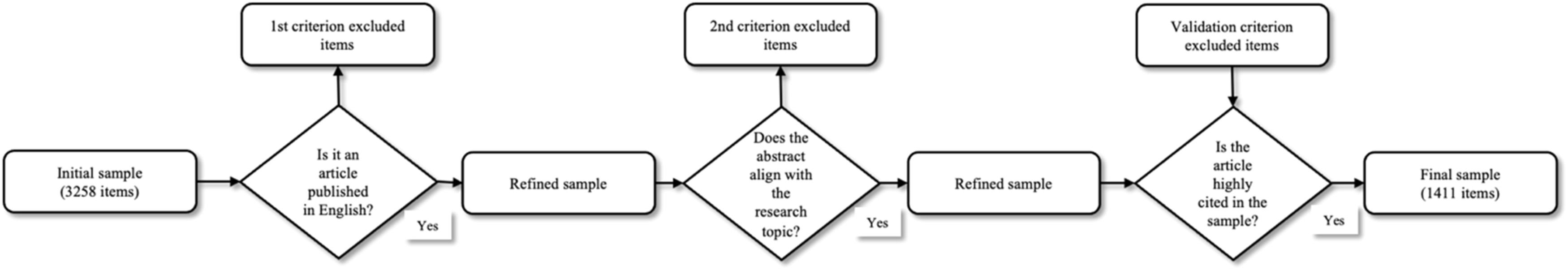

Data pre-processingTo improve the quality of the sample, both exclusion and inclusion criteria were employed. Specifically, regarding the exclusion criteria, a) only peer-reviewed journal articles published in English were included in the refined sample (Centobelli et al., 2016; Centobelli et al., 2022), and b) only articles whose abstracts were found to be relevant to the issue were included in the following analysis (Saunila, 2020; Schlackl et al., 2022). In particular, after the application of the first exclusion criterion, 2147 articles were selected. To evaluate abstract eligibility, three contributors separately checked 715 abstracts. At the end of this first screening, 92 abstracts needed further review to be evaluated. For those abstracts, all three contributors independently evaluated the eligibility and those obtaining at least 2 out of 3 votes were included in the refined sample. Furthermore, a validation criterion was implemented to enhance the accuracy and validity of the process, reducing the likelihood of overlooking any articles inside this domain and mitigating the potential risk of diluting sample relevance due to the exclusion of KM-related words in the research string. Specifically, the validation process led to the inclusion in the final sample of highly-cited contributions from the refined sample search which may have been excluded by the initial research string (snowball sampling). More specifically, all citations from the refined sample were retrieved and the top 10% most cited references were automatically identified. These highly-cited contributions were then compared to the refined sample and, if not already included and if deemed relevant to the purpose of the research, they were added to the final sample.

This validation criterion enabled the authors to locate and retrieve significant publications referenced in the literature that had not been included in the databases selected and keyword search (Cerchione & Esposito, 2016). The outcome yielded a total of 1411 papers. Fig. 2 shows the logical steps of data pre-processing.

ResultsDescriptive analysisChronological distribution of the papersAs shown in Fig. 3, GenAI is a recently emerging subject. Results showing the distribution of research papers over time indicate that the earliest paper in the sample was published in 2018 but there has only been a substantial rise in the number of papers since 2023. The reason for this gap is evident. Although a comprehensive understanding of what would later be known as GenAI was first introduced in 2014 by Goodfellow et al. (2014) in their article on generative adversarial networks, the topic remained somewhat unclear for people in other sectors until the emergence of generative pre-trained transformer models in 2023; it was then that their ability to generate high-quality text output was demonstrated (Head et al., 2023). ChatGPT reached approximately 100 million users within two months of its release (Hsu & Ching, 2023). Prior to that date, only articles that discussed the technical aspects of GenAI mentioned the topic. In addition, from a KM perspective, it is particularly important to note that the first two articles explicitly referring to GenAI addressed the production of new knowledge, specifically in the development of new drugs (Gupta et al., 2018; Merk et al., 2018). This aspect highlights the significant interest in what is arguably the most distinctive trait of GenAI: its ability to generate what could be defined as new knowledge.

Geographical distribution of papersAnalysing the distribution of scientific papers across different countries is essential to identify research hubs and various groups working on a topic. In addition, it provides a deeper understanding of global and regional interests in developing a disruptive technology such as this one. As expected, interest in GenAI is widespread across the world’s most developed countries. Fig. 4 shows the top 15 countries that produce the most.

However, very few publications originate from countries or regions where KM research has traditionally been more widespread, which aligns with the observed gap indicating that the GenAI-KM connection is not yet well developed in the core KM research community. This pattern indicates the originality of our research, as it underlines the need for a review that brings together contributions from both dominant GenAI-producing nations and underrepresented but theoretically significant KM contexts.

Distribution of papers by subject areaThis analysis reveals that GenAI is a widely studied topic across multiple subject areas. As shown in Fig. 5, the most productive area is the social sciences (45 % of the papers), followed by engineering and technology (32 % of the papers). This result suggests that the high number of publications in the social sciences can be attributed to the growing interest in using GenAI to analyse social data, develop educational tools and enhance research methodologies. Meanwhile, the engineering field is at the core of AI development and a major research area within computer science, with a focus on model development and algorithm improvements. The third most prominent field is the health sector (13 % of papers), in which GenAI is regarded both as an opportunity – for instance in the discovery of new drugs – and a challenge, as intricate patterns must be made comprehensible for human practitioners.

Distribution of papers across journalsAn extensive analysis was conducted to identify journals that publish research articles related to GenAI. This analysis helped uncover the fields of study that demonstrate interest in this topic, as journals are representative of specific clusters of scientific disciplines. The sample of 1411 articles was published in 782 different journals, indicating that literature is highly dispersed across many sources. Table 1 summarizes the top 10 contributing journals in term of the number of published articles.

Top contributing sources.

While this fragmentation could be caused by the interdisciplinary nature of GenAI, it also reveals a lack of centralized scholarly dialogue, which may slow the development of interdisciplinary theoretical models. From a KM perspective, this trend underscores the need to build integrative frameworks that can bridge current disciplinary silos and establish a clearer epistemological foundation for how GenAI should be studied within KM contexts. It is noteworthy that journals focusing on KM are absent from the higher part of the ranking, which supports the assumption that this field has not been sufficiently studied in terms of how this new technology fosters knowledge generation. This finding is consistent with the gaps identified and highlights the role that our review can have in drawing together perspectives from diverse disciplines, into a framework that can direct future KM-focused research on GenAI. However, this trend, which has also been observed in other domains (Cerchione & Esposito, 2016), may be an opportunity. It is likely that in future there will be growing interest in the topic examined by journals that focus on KM. This view is supported by the fact that the most cited paper on GenAI was published in a journal dedicated, among other areas, to KM. It is pertinent to note that this journal analysis focuses on the quantity of published articles. As a result, journals that have published only a few papers, regardless of the number of citations they earned, are ranked last.

Most productive authorsIn terms of authorship, 4489 different authors have contributed to the production of the 1411 sample articles. The average number of authors per document is 4. In total, 276 authors appear in single-authored documents, which amounts to 300 single-authored papers. In addition, 64 % of the authors had published only one paper, leading to the conclusion that GenAI appears to be a field of both research verticalization and diversification (Ertz & Leblanc-Proulx, 2018). Table 2 summarizes the top 15 contributing researchers based on the number of published articles as first or single author.

Most relevant contributionsTable 3 shows the most relevant contributions based on the number of citations received. There is little to no correspondence between the number of articles published by an author and the citations they received, suggesting that, in this field, a high publication volume does not necessarily result in a significant theoretical contribution.

Most relevant contributions.

In this study, science mapping was implemented through network analysis. Over the year, various software tools have been developed to perform network analysis in order to map scientific data. This research utilizes VOSviewer (vers. 1.6.20) to execute science mapping analyses, particularly focusing on co-citation and co-occurrence analyses. VOSviewer is a publicly available software commonly employed to construct and display network maps based on bibliometric data (Van Eck & Waltman, 2010). This software offers visual representation of data in a way that accurately represents relationships between items by positioning them in a two-dimensional space. More specifically, the VOSviewer two-dimensional visualization map consists of nodes and edges. Nodes are the map’s unit of analysis and can encompass articles, authors, nations, journals, and organizations. The size of the nodes and their associated label styles are determined by the number of times they occur. In particular, larger nodes correspond to a higher frequency of occurrence. Nodes are connected through edges, which indicate the existence of a relationship between them. Links representing co-citation highlight connections between the articles, whereas links representing co-occurrence show connections between keywords. Each connection in the graph is assigned a weight, which is a positive numerical value that can vary based on the strength of interaction between elements. According to Van Nunen et al. (2018), the axes structure resulting from visualization of the network obtained by employing this software does not have inherent meaning, which make flexible interpretation of the maps depicted possible. Proximity between objects signifies a strong relationship, whereas greater distances between items indicate weaker relationships. Nodes within the network can be categorized into clusters based on their shared attributes. To standardize the strength of the links connecting nodes and to visualize the maps, the software employs the association strength normalization method (Eck & Waltman, 2009).

Science mappingIntellectual structure: co-citation analysis of authors citedOur examination offers a detailed understanding of the intellectual structure, dynamics, and interdisciplinary relationships within a specific subject area. By providing a comprehensive overview of the most relevant authors and their contributions, it highlights major research themes and clusters, while also identifying future developments. This approach is a powerful tool to comprehend the academic network structure and the evolution of knowledge within a particular field of study. The graph displayed in Fig. 6 was generated using VOSviewer, setting the minimum number of citations to 60, which produced 172 authors cited a total of 17,849 times.

Table 4 presents the most frequently co-cited authors, categorized into four thematic groupings. Leading with 268 and 269 co-citations respectively, Zhang Y and Iazaroiu G occupy the top echelon of the list; Li Y follows with 260 co-citations. Liu Y, Wang X, and Wang Y each have 240 co-citations; Li X has 215 and Nica E has 213.

Clusters resulting from co-citation analysis.

Data analysis identifies four distinct clusters that link authors with similar research traits. Leading authors in cluster 1 are Zang Y, who investigated the potential co-creation of data and content in tourism (Zhang & Prebensen, 2024), and Li Y, who emphasized the importance of protecting the data generated. Due to great emphasis in scientific communities in the Far East on the technical aspects of GenAI and data manipulation, this cluster mostly consists of researchers from that region. In contrast, Western scholars tend to focus on GenAI’s applications in managerial and educational settings, along with the related ethical issues. This cluster encompasses numerous models for the implementation of artificial intelligence systems in many different fields. In cluster 2, Dwivedi Y K claimed that GenAI is a transformative tool capable of fostering unprecedented breakthroughs across diverse sectors and improving organizational efficiency; his perspective is reinforced by numerous studies stressing the medical innovations made possible by GenAI solutions. In contrast, Wu J, the top author in cluster 3, examined the ethical challenges and consequences linked to the evolution and use of GenAI (Yang et al., 2024). Along with several colleagues in this group, the author explored key concerns of GenAI, such as bias, misinformation, and privacy violations, and suggested some solutions to mitigate these issues. The primary contributor to cluster 4 is Lazaroiu G (269 co-citations), who investigated the factors driving the widespread adoption of GenAI technology in education. His studies have highlighted the advantages, difficulties, and possible pathways to integrate this technology in classroom environments.

Conceptual structure: co-occurrence analysis of keywordsKeywords provide a concise summary of the main themes discussed in an article. Additionally, they may encompass the methodologies, aims, purposes, and fields of study explored in the research (Donthu et al., 2023). For this reason, keyword analysis is a quantitative method used to systematically identify connections between sub-fields. There is a direct correlation between the frequency of keyword occurrences and the level of attention directed towards a topic. A total of 4600 distinct keywords were found across the 1411 sample articles. Using VOSviewer, keywords were analysed based on their co-occurrence patterns. The resulting graph was generated by setting the minimum keyword occurrence threshold to 10, resulting in 145 keywords being included in the analysis. The results clearly highlight five thematic clusters (Fig. 7):

- –

Cluster 1: GenAI for data synthesis (green cluster with 40 keywords)

- –

Cluster 2: GenAI for knowledge codification (red cluster with 40 keywords)

- –

Cluster 3: GenAI explainability and transparency (blue cluster with 27 keywords)

- –

Cluster 4: GenAI data absorption and ethical implications (yellow cluster with 23 keywords)

- –

Cluster 5: GenAI for knowledge generation (purple cluster with 15 keywords)

Cluster 1: GenAI for data synthesis

This cluster was generated through keyword co-occurrence analysis and includes articles with strong alignment to terms such as auto encoders, case-studies, classification (of information), computational modelling, computer vision, data mining, data models, data privacy, decision making, deep learning, diagnosis, diffusion models, generative adversarial networks, image enhancement, image generations, image processing, learning algorithms, learning systems, multi-modal, performance, reinforcement learning, semantics, social media, e-learning, and training. The focus of this cluster is on the capability of GenAI to autonomously produce new data. This is particularly relevant in clinical research, where studies rely on high-quality medical datasets, which are extremely costly to obtain and often restricted by privacy and regulatory constraints. In this context, synthetic data generation offers an opportunity to overcome these limitations by enabling easier access to usable data. There is substantial evidence from various studies in this cluster that directly correlate with this activity. For instance, Eckardt et al. (2023) combine deep learning methods with normalization algorithms to develop synthetic data based on a real sample of patients. Furthermore, within this area, this cluster also suggests that data can be generated in the form of images. The potential to improve image quality and data representations is referenced in the work of Khosravi et al. (2023), where the authors proposed a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) trained on a large number of pelvis radiographs. The outcomes of this research demonstrated a high degree of similarity between the generated and original images. Following a similar approach, Nie et al. (2024) introduced skyGPT, a forecast model that predicts the dynamics of future weather conditions based on historical sky images in order to improve the accuracy of solar photovoltaic output predictions. Also, in another application of image generation, in their article Paananen et al. (2023) explored the possibility of improving creativity during architectural design process through the use of text-to-image generators as a tool that further stimulates human imagination. As previously mentioned, clinical research requires more and more data, and that is also true in education, where it is often the responsibility of classroom teachers to develop instructional materials that align with students’ needs and course requirements. In their study, Zheng & Stewart (2024) examined ethical approaches to collaborating with GenAI to create instructional materials that are culturally suitable. In the KM field, this cluster focuses on the process of data acquisition. The relevance of this new type of artificially synthetized data, generated by GenAI technology, is twofold. Firstly, it plays a crucial role in boosting research, especially in domains characterized by a lack of data, where it may enable the production of meaningful insights that would otherwise be inaccessible. Secondly, it could enhance better educational environments through the development of personalized materials and the introduction of new learning processes.

Cluster 2: GenAI for knowledge codification

This cluster was derived from our co-occurrence network analysis and included all articles centred around keywords such as academic integrity, AI ethics, artificial intelligence tools, assessment, behavioural research, chatbots, ChatGPT, commerce, creativity, critical thinking, curriculum, education, education computing, engineering education, ethical technology, ethics, higher education, human experiment, innovation, knowledge management, learning, marketing, pedagogy, plagiarism, students, systematic review, teachers, teaching, technology adoption, virtual reality, and writing. The main theme is the application of GenAI to codify and share human knowledge. The articles in this cluster deal with the use of this technology to effectively handle, share, and improve human knowledge across various domains, especially in educational settings. The study by Korzynski et al. (2023), for instance, investigates the potential that GenAI technologies such as ChatGPT have to provide an innovative framework to manage theories and concepts. In addition, this cluster explores the role of GenAI in encoding knowledge in educational systems and enhancing teaching and learning processes. This idea is supported by a significant number of articles concerning the use of GenAI in education. Hsu & Ching (2023) discuss the broad scope of GenAI, its opportunities and hurdles in the field of education, along with related challenges. Tlili et al. (2023), in examining the use of ChatGPT among early adopters, indicate multiple concerns, such as academic dishonesty, deceptive privacy practices, and manipulation. Some authors have further demonstrated the potential of GenAI tools. This is the case with Pavlik (2023), whose contribution is a collaboration between a human journalist, a media professor, and the famous OpenAI chatbot. Their research aims to showcase the capabilities and limitations of this technology, as well as to provide insights into the impact that GenAI has on journalism and media education. On the whole, the findings of many studies suggest different strategies for the responsible implementation of GenAI tools in education, but few provide explicit guidance on how to achieve this. To address this issue, Lim et al. (2023) indicate a broader involvement of management educators, as GenAI is considered a game-changer for future generations. Analysis of this cluster also comprises the ethical considerations of using GenAI to manage and share knowledge and of ensuring integrity and trustworthiness in educational tools powered by this technology. To further explore this topic, Watermeyer et al. (2024) surveyed 284 British academics to examine their use of this novel technology. The findings indicate that the increasing adoption of these tools in academia presents an opportunity to promote engagement with high-quality research and rigorous research practices. In line with the same concerns, Dwivedi et al. (2023) sought to explore the ethical and legal challenges of this tool and its potential impact on social structures. The findings of their research indicate that GenAI is expected to provide substantial benefits, despite mixed opinions regarding the need for restrictions and legislation on its use. Another relevant aspect investigated in this cluster is how GenAI influences human learning processes and research methodologies. Cooper (2023) warns of the danger of promoting AI systems as the ultimate source of knowledge. This can happen when a single truth is accepted without solid evidence or without supporting it with sufficient demonstrations. To address this fundamental issue, educators have the essential function of illustrating responsible use of these technologies and emphasizing the importance of critical thinking. In particular, educators must carefully assess AI-generated content and customize it for their own educational settings. These concerns regarding academic integrity are shared by various articles, as in the case of Sullivan et al. (2023), whose study investigated the influence of ChatGPT on higher education. The study leads us to the consideration that while these tools continue to be promising for communication and information retrieval, it is vital to assess their ethical and responsible use. Furthermore, this cluster highlights a lack of public discussion regarding the manner in which GenAI could enhance students’ engagement and success, particularly for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. From a KM perspective, this cluster focuses on using GenAI to codify, manage and disseminate human knowledge. This technology is essential for structuring human knowledge into accessible formats that can be easily retrieved and applied. The primary objective is to develop a systematic approach for using GenAI to arrange and disseminate knowledge, guaranteeing its accessibility, reliability, and efficient application in various domains. This is especially relevant in education, where it helps to improve the effectiveness of teaching and learning. In addition, the ethical considerations discussed in this cluster are vital to guarantee that the knowledge shared through GenAI remains reliable and trustworthy, in accordance with the fundamental principles of KM.

Cluster 3: GenAI explainability and transparency

This cluster derived from our co-occurrence network analysis and included all articles centred around keywords such as accuracy, clinical article, clinical decision making, clinical practice, communication, controlled study, diagnostic accuracy, humans, interpersonal communication, knowledge, language, major clinical study, medical education, patient education, physician, practice guideline, privacy, proof of concept, reliability, and reproducibility. The presence of terms like language, communication, patient education, and interpersonal communication underscores the cluster’s focus on the view that the knowledge produced by GenAI must be explainable, interpretable and trusted in human-centred settings. This cluster addresses the need to understand how GenAI makes decisions, which is particularly relevant in healthcare, where accuracy and trust are crucial. The potential benefits of using large language models (LLMs) in the healthcare sector are significant and range from simplifying clinical administrative processes to addressing patients’ inquiries regarding their individual health concerns. Given these premises, regulating GenAI in healthcare without limiting its revolutionary potential is a priority, in order to guarantee safety, preserve ethical norms, and preserve patient confidentiality. From this standpoint, Meskó & Topol (2023) argue that authorities should develop regulatory frameworks to guide healthcare professionals and patients in employing LLMs responsibly, mitigating negative implications and preventing them from exposing their data to privacy violations. Their work provides a concise overview of feasible recommendations that regulators can implement to realize this ambition. The need for regulatory frameworks becomes even more pressing if we consider the enormous potential GenAI expresses in helping medical professionals with rapid diagnoses in critical and time-sensitive contexts. In such cases, the effective integration of GenAI tools into clinical workflows could enable timely alerts to life-threatening conditions, while also supporting imaging interpretation and documentation. Huang et al. (2023), for instance, highlight the value of GenAI in optimizing emergency department care by producing draft radiology reports based on input images. The results clearly demonstrate that while the proposed GenAI model produces clinical accuracy similar to radiologist reports, they can even exceed human colleagues in terms of textual quality. This is also true in normal diagnoses, as Pagano et al. (2023) confirmed the accuracy of ChatGPT-4 in diagnosing osteoarthritis, as well as in prescribing appropriate treatments. Their study, based on anonymized medical data as a ground truth sample, reinforces the significant potential LLMs have in detecting pathological situations and confirms the convenience of using them, at the very least, as support tools for orthopaedic specialists. However, transparency is essential to foster trust among healthcare professionals and patients regarding AI-based models, particularly in domains where the predictive powers of GenAI surpass human cognitive capacity in extracting meaningful insights from vast datasets. To address this issue, Lang et al. (2024) propose an explainability framework that makes the formulation of hypotheses possible through feature visualizations, in order to facilitate the extraction of new knowledge from GenAI models. Another important aspect explored in this cluster is the possible use of GenAI in facilitating communication exchanges between patients and healthcare providers. This can be accomplished through the use of chatbots that respond to patient inquiries about their health condition. Cai et al. (2023) assessed the ability of GenAI models to answer board certification exam practice questions in ophthalmology. The findings of this research showed that LLMs can achieve performance levels comparable to human experts in answering questions regarding the latest clinical knowledge in the field. Another similar study was presented by Chervenak et al. (2023) but with the aim of comparing the responses of LLMs to reputable sources regarding fertility related topics. Although the results can be considered positive, high numbers of hallucinations indicate that there is still room for improvement in the performance of conversational agents in the medical field. This approach is also being explored in mental healthcare, where LLMs may provide a significant contribution to achieve global equity in care delivery. In particular, when exploring this field, Blease & Torous (2023) indicated the potential long-term benefits that patients and healthcare providers may experience thanks to these technologies, if used appropriately. This cluster also explores the privacy challenges of LLMs in healthcare. Romano et al. (2023) underscore the ability of LLMs to analyse vast amounts of health records and provide valuable insights in the field of neurology. On the other hand, research also points to the possible ethical and technical difficulties posed by this innovative tool, including those related to privacy and data security, potential biases in the data used to train the models, and the need to rigorously validate results. This cluster centres on ensuring the openness and transparency of GenAI systems with reference to the healthcare sector. These studies emphasize the importance of understanding GenAI’s decision-making processes, with a specific focus on the reliability, reproducibility, and transparency of its choices. From a KM perspective, this cluster is primarily concerned with knowledge utilization and knowledge sharing. Understanding AI decision-making processes makes it possible to use artificially generated knowledge in sectors where its precision and trustworthiness are crucial. Moreover, the clear and transparent communication of model decisions, coupled with educational initiatives aiming to enhance AI literacy among professionals, is central to an efficient knowledge dissemination strategy. These measures ensure that newly generated insights are easily understandable, reliable, and seamlessly incorporated into real-world practices.

Cluster 4: GenAI data absorption and ethical implications

This cluster was derived from our co-occurrence network analysis and included all articles centred around keywords such as BARD, chatbot, conversational agents, GPT, language model, language processing, large language models, LLMs, mental health, natural language processing, natural language processing systems, natural languages, NLP, and prompt engineering. The prominence of terms like cybersecurity, NLP and computational linguistics further points to concerns regarding the ethical boundaries of GenAI interactions and the risks of unintentional data absorption. This cluster is characterized by its interdisciplinary nature, bringing together research from multiple fields. The articles in this cluster explicitly address the potential risk of unintentional data absorption by AI systems, especially when they interact with humans. The aforementioned scenario can lead to significant ethical problems, primarily regarding privacy or unexpected consequences of data usage. Min et al. (2024) examined the expansion of pre-trained language models (PLMs) and their ability to assimilate extensive quantities of data from user interactions. Similarly, Ooi et al. (2023) emphasized the rapid advancement of AI technology and related ethical issues, such as unintentional data assimilation. In addition, an analysis of conversational agents (CAs) and their development, as demonstrated in Schöbel et al. (2024), illustrates the real-world consequences of AI systems unintentionally assimilating user data. According to most studies in this cluster, the implementation of ethical guidelines appears to be the key strategy for mitigating the risk of possible AI data absorption. In this context, regulatory frameworks can play a crucial role in ensuring ethical AI practices. From a KM standpoint, this cluster addresses the two key processes of data acquisition and knowledge sharing. The first process is seen in the enormous amount of unintended data provided by humans during interactions with AI systems, which can lead to ethical and privacy concerns. The latter process, namely knowledge sharing, is also involved, because AI systems such as chatbots, though not human, can act as entities able to absorb and share information. Once again, albeit from a different perspective, the need for ethical guidelines seems to have a pivotal role in managing the complexities of data acquisition and knowledge sharing in GenAI environments.

Cluster 5: GenAI for knowledge generation

This cluster was derived from our co-occurrence network analysis and included all articles centred around keywords such as algorithm, algorithms, automation, chemistry, diagnostic imaging, drug design, drug development, drug discovery, image analysis, task analysis, and simulation. Other significant keywords like personalized medicine, procedures and benchmarking suggest a strong emphasis on the creation of novel insights through GenAI, particularly in the healthcare domain. More precisely, this cluster focuses on the capacity that GenAI has to generate novel medical insights. Articles reveal the use of GenAI to produce new insights in the fields of drug development, which could potentially satisfy the need for new medications. Traditional approaches are mostly based on screening large collections of pre-existing chemical compounds in order to discover potential drug candidates. In contrast, de novo drug design, facilitated by generative technologies, enables scientists to identify new compounds tailored to specific biological receptors. In this regard, Macedo et al. (2024) described the process of optimizing and refining medGAN, a deep learning model that combines Wasserstein generative adversarial networks with graph convolutional networks. This model is specifically designed to produce novel quinoline-scaffold compounds from sophisticated molecular graphs. Krishnan et al. (2024), on the other hand, address the challenge of validating newly designed drug categories by introducing forward synthesis-based generative methods. Their proposed method helps overcome one of the major limitations of AI-based drug design by designing novel synthesizable target-specific molecules. Wang et al. (2024) explored this field further. More specifically, the authors devised an original method in this domain that employs generative reinforcement learning which systematically samples all possible chemical compounds, including the purely hypothetical ones, in order to produce novel molecular structures. In line with this innovative product design perspective, Shimizu et al. (2023) identified a new approach to generating compounds without violating the intellectual property rights of specific molecular structures, which is a crucial but often overlooked aspect in the field of drug discovery. According to the authors, their research demonstrates how pharmaceutical patents can be used to generate new molecules with structures similar to previously developed drugs, thus avoiding licensing constraints that impede innovation. All in all, this last cluster deals with a knowledge generation process which is considered the highest and possibly the most impactful stage of all KM processes. GenAI significantly enhances the generation of new scientific and medical knowledge by producing novel insights and potential solutions that traditional methods might overlook. Furthermore, the focus in this cluster is on validating newly generated insights, which is in line with the KM approach of guaranteeing the reliability and applicability of new knowledge. This approach ensures that scientific progress is both pioneering and reliable.

The examples in this cluster draw attention to a potential form of knowledge generation which seems to diverge from the traditional KM cycle described by well-established theoretical models. According to the SECI model (Nonaka, 1994), knowledge creation is considered to be the result of the conversion of tacit to explicit knowledge through human interaction, shared experience and interpretation. In contrast, when one considers GenAI, this generation is obtained through the statistical recombination of data patterns. There is no inner intentionality or embedded meaning without post-processed user interpretation. This divergence can also be noticed when considering other foundation models. Andrews and Delahaye’s model (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000) frames knowledge creation as a socially constructed and interpretative act, shaped by shared meaning and dialogue. GenAI-generated insights, in contrast, are pre-contextualized outputs, without social negotiation until they are presented as output to human actors and reviewed. A similar consideration emerges in the contrast between GenAI-powered knowledge production and Von Krogh’s (Von Krogh et Al., 2000) conceptualization of conditions that enable knowledge creation: intention, fluctuation and chaos, redundancy, autonomy and creative dialogue. GenAI lacks most of these; indeed, it has no intention, cannot dialogue and operates within optimization constraints. Traditional KM models attempt to describe the knowledge creation process by emphasizing contextual grounding and social validation, whereas GenAI outputs are mainly based on pattern recognition, generative inference and probabilistic relevance. What must be investigated in the near future is whether such outputs can be considered to be a sort of ‘knowledge’ even when they are not socially experienced or interpreted. From this viewpoint, this cluster seems to suggest the need for a hybrid theory of knowledge generation in which GenAI informational artifacts are integrated in knowledge creation processes.

Article classificationFollowing the identification of five thematic clusters through keyword co-occurrence analysis, a semi-automated article classification procedure was implemented. The core of this approach was the structured keyword co-occurrence analysis, which produced five keyword clusters using VOSviewer. However, the authors added an additional step by classifying each individual article into a corresponding thematic cluster. As VOSviewer does not directly assign articles to co-occurrence keyword-based clusters, the authors propose a semi-automatic and transparent procedure that ensures replicability. To this end, it is important to note that, in addition to cluster assignments, VOSviewer computes betweenness centrality, which quantifies how often a keyword lies on the shortest path between other keywords, indicating its role as a conceptual bridge, and closeness centrality, which measures the average inverse distance to all other nodes, which identifies keywords that are most centrally positioned in the overall thematic space and consequently conceptually central to the overall topic.

For each cluster, the most conceptually central keywords, using closeness centrality scores, were identified. For each article, all associated keywords were collected and refined. Specifically, we excluded all keywords considered not relevant to the aims of our study and covering broad topics (such as deep learning and artificial intelligence) that were expected to be present across all clusters. Finally, a matching algorithm that compared refined keywords with high-centrality keywords was implemented. Due to potential paper alignment with more than one cluster, each article was assigned to the cluster that exhibited the highest number of refined, central matching keywords, so as to maximize the relevance and accuracy of the classification process. This approach, visually presented in Fig. 8, ensured that article classification was data-driven but also conceptually coherent.

Classification results are shown in Fig. 9. Cluster 2 has the highest population, accounting for 48% of the total number of publications. Cluster 1 and cluster 2 collectively make up 79 % of the entire dataset. This result reflects the fact that the literature has extensively examined the use of GenAI to codify explicit knowledge in the context of education and the potential application of this novel technology to substitute real-world data. Cluster 3, despite a considerable gap, as indicated by the number of papers included, highlights the ethical implications and regulatory concerns related to the previously mentioned themes, from which, in a sense, they derive. Cluster 4 corresponds to only 8 % of the total count. However, this outcome can be attributed to the methods used to categorize the articles, which prioritized strong alignment with predefined keywords. For this reason, only a limited number of articles was included in this cluster. Nevertheless, most of the articles have some indirect references to the major theme emphasized in cluster 4. Cluster 5 is the smallest cluster, reflecting the fact that knowledge generation, being the final stage of artificial knowledge creation, is a highly specialized research focus with a limited number of publications.

DiscussionRethinking the SECI model in the GenAI eraThe findings from this bibliometric review highlight GenAI’s inner potential to radically transform KM processes. All in all, our results confirm the view that GenAI applications are spreading across diverse sectors, although healthcare and medical domains emerge prominently. This trend can especially be observed in clusters 1 and 5, where the potential for synthetic data as well as novel knowledge production is evident (Eckardt et al., 2023; Macedo et al., 2024).

To analyse these findings from a theoretical standpoint, this section draws on the SECI model (Nonaka, 1994), which remains one of the most influential and widely adopted frameworks for understanding knowledge creation in KM research. The model conceptualizes knowledge generation as a dynamic interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge across four phases: socialization, externalization, combination and internalization (Fig. 10).

The disruptive potential of GenAI challenges this model at multiple stages. For instance, many contributions in cluster 2 (knowledge codification) demonstrate how GenAI facilitates the automatic externalization of fragmented ideas into coherent explicit formats, a task traditionally performed by humans. Similarly, cluster 5 (knowledge generation) reveals GenAI’s capacity to combine vast volumes of structured and unstructured data in ways that mirror, or even exceed, human combination processes. Similarly, it can assist humans in the internalization process by providing explanations and tailored content that facilitate users’ experiential understanding. In this way, GenAI acts as a supportive environment rather than as a participant, simulating a form of machine-guided learning even without real tacit absorption. Moreover, GenAI tools, particularly conversational agents, may create the illusion of socialization, mimicking interpersonal knowledge exchange through dialogue-like interactions. However, these interactions suffer from limited epistemic depth, as they are not grounded in shared human experience. While this surrogate of socialization has some positive aspects, it also highlights the need to distinguish between the effectiveness of simulated dialogue and genuine tacit-to-tacit knowledge transfer. Table 5 summarizes the impact GenAI has on the SECI phases. In light of earlier points, the findings of this study indicate the need for a re-examination of the SECI model that considers GenAI’s growing role in knowledge processes. More precisely, these observations point to a hybrid extension of the model, where human and artificial actors co-create, validate and iterate knowledge across overlapping yet distinct learning loops.

GenAI impact on SECI phases.

| SECIPhase | Traditional KM Role(Nonaka, 1994) | GenAI impact on SECI phases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socialization | Tacit-to-tacit knowledge sharing through shared experiences, direct observation, mentoring, informal dialogue. | Human–machine interaction where users iteratively explore ideas through conversational prompting (e.g., co-writing, brainstorming). Pavlik, (2023); Min et al. (2024) | Interaction lacks emotional or experiential depth. Moreover, trust and interpretability issues may arise. Blease & Torous (2023) |

| Externalization | Articulation of tacit knowledge into explicit concepts (writing, diagrams, metaphors). | Helping users formulate thoughts as structured outputs. Hsu & Ching (2023); Tlili et al. (2023) | The articulation still originates from human tacit knowledge. |

| Combination | Integration and systematization of explicit knowledge (reports, databases). | Finding patterns across vast data sources to generate new narratives or frameworks. Watermeyer et al. (2024); Korzynski et al. (2023); Nie et al. (2024) |

|

| Internalization | Absorption of explicit knowledge into tacit understanding through learning, practice and reflection. | Humans internalize AI-generated outputs via training, scenario simulation, or decision support. GenAI can also simulate learning environments (e.g., AI tutors). Zheng & Stewart (2024); Lim et al. (2023); Krishnan et al. (2024) |

|

It is notable that, at a deeper level of analysis, many contributions found in the literature implicitly point to the consideration that GenAI is not only automating aspects of KM (Seeber et al., 2020; Brem et al., 2023) but also reshaping its foundational logic. Treating GenAI purely as a support technology appears too reductive. Instead, the evidence suggests that this disruptive technology introduces a new epistemic dimension to KM, in which knowledge can be generated through human-machine interaction. Our discussion section further explores this consideration by proposing the existence of a machine dimension in knowledge generation, operating in a parallel manner with the human dimension described in Nonaka’s SECI model (Nonaka, 1994). In addition, the authors identified two essential components of this machine dimension, namely data and artificial knowledge, that emerged from cluster findings, particularly from clusters 1 and 5.

The machine dimensionThe emergence of GenAI as a non-human actor in knowledge processes calls for reconsideration of foundational KM frameworks. Results from this study suggest that GenAI does not merely support traditional KM processes, it introduces a machine dimension of knowledge creation that operates parallel to the human one. This conceptual expansion becomes especially evident when visualizing how GenAI maps onto, or diverges from, the four traditional SECI phases (as illustrated in Fig. 11). In specific SECI phases, GenAI aligns with existing knowledge creation processes. This is the case when it assists users in externalizing tacit ideas into structured outputs (Fig. 11, number 2) and facilitates internalization through scenario simulation (Fig. 11, number 4). However, other impacts diverge from traditional SECI logic, revealing knowledge dynamics better situated within a machine-driven epistemic loop. For instance, there is conversational prompting, which simulates aspects of socialization (Fig. 11, number 1). Similarly, GenAI’s ability to produce synthetic datasets and synthesize patterns across them (Fig. 11, number 3) reflects a form of synthetic combination that operates independently of human cognitive structuring. These divergences suggest that GenAI is not simply participating in human knowledge creation cycles but is generating novel knowledge dynamics through a separate machine-driven loop.

This hybrid SECI framework provides a foundation for future knowledge management models that reflect the interplay between human cognition and artificial intelligence. More specifically, the machine dimension operates in a distinct but interconnected layer with respect to the human spiral. As schematized in Fig. 12, the machine dimension can be framed as a complementary loop, distinct from, but potentially interlinked with, the human SECI process.

A further theoretical distinction between human and machine dimensions arises when considering GenAI output generation in light of the DIKW framework. Traditional human knowledge creation typically evolves from data to wisdom in a bottom-up process (Rowley, 2007), whereas GenAI systems frequently function in a reverse direction. They are trained on organized, explicit knowledge artifacts and employ these to produce innovative outputs that mimic data or raw information. This inversion may be regarded as a type of synthetic epistemology, in which meaning is deconstructed and reconstructed into novel informational formats. This reversal questions the basic principles of conventional knowledge management, especially the notion that knowledge is derived from data. These observations highlight the need to revise KM theory to incorporate non-human epistemic agents. The machine dimension is not merely an augmentation, but a conceptual expansion that opens new research directions on how humans and machines co-create knowledge in organizational contexts. Beyond the preliminary attempt to frame the machine dimension in established KM frameworks, its mechanics drastically differ from those described in the human dimension and their possible points of contact need further empirical studies to be fully described and formalized. This formalization lies far beyond the scope of this study. However, within the limits imposed by the nature of this study, following a deeper analysis and qualitative interpretation of the clusters that emerged in the literature, two main components of this new epistemic dimension clearly arise: data and artificial knowledge.

Data as machine tacit knowledgeA foundational consideration revealed in cluster 1 (GenAI for data synthesis) is that GenAI relies on extensive datasets for training, resulting in novel, contextually relevant outputs that emulate human-level knowledge. Research by Eckardt et al. (2023) and Khosravi et al. (2023) demonstrated that synthetic datasets generated by GenAI can successfully recreate complex real-world scenarios to achieve experimental objectives, such as replicating radiological images or simulating clinical environments. This outcome raises a fundamental question: given that generative AI utilizes data to contextualize and learn, similar to the way individuals employ their tacit knowledge, can data act as a type of tacit knowledge for machines? Tacit knowledge is defined in the KM literature as being highly personal, context-dependent and challenging to formalize (Polanyi, 1966; Nonaka, 1994; Bateson, 1979). Despite their lack of beliefs or intuition, the ability of machines to infer patterns from data and reconstruct absent context (Chen et al., 2018) mirrors human reliance on past experiences to interpret complex situations. While some scholars exclude the idea that machines may possess such tacit knowledge (Johannessen et al., 2001), many others propose a continuum-based view that suggests that lower levels of tacit knowledge can be digitally manifested (Lin & Ha, 2015; Fakhar Manesh et al., 2021; Chennamaneni & Teng, 2011). From this perspective, data functions as machine-internal tacit knowledge: not articulated in conventional language but deeply embedded in probabilistic weights, vectors and representational layers in deep learning architectures. Furthermore, just as experience and introspection shape the quality of human tacit knowledge, the quality and variety of datasets significantly influence the effectiveness and contextual understanding of GenAI models (Mikalef & Gupta, 2021). Cluster 1 shows that GenAI can emulate real-world scenarios through access to extensive synthetic auto-generated datasets, a capability that aligns with human intuition in difficult problem-solving situations.

Artificial knowledgeCluster 5 provides compelling evidence that GenAI systems can go beyond data manipulation to generate novel insights (Kim, 2024), a function traditionally seen as the apex of human knowledge creation. For instance, articles such as Macedo et al. (2024) and Krishnan et al. (2024) describe how GenAI is used in de novo drug discovery, creating entirely new chemical structures tailored to specific therapeutic needs. These systems do not merely retrieve existing knowledge; they create new functional outputs based on complex associations. This capacity invites reflection on whether GenAI can be said to produce some kind of ‘knowledge’. If we define knowledge as a combination of contextual information and rules (Pearlson et al., 2020), or as information structured and applied to solve problems (Turban et al., 2005), GenAI appears to satisfy both criteria. It processes data into usable insights and, increasingly, offers outputs that guide human decision-making in, for example, diagnosing diseases or proposing technical designs, as seen in the literature analysed. Drawing on Jashapara (2004), we may distinguish between actionable knowledge, which is used to find practical solutions, and conceptual knowledge, which is used to make sense of complex systems. GenAI clearly excels at the former. It creates responses, drafts and designs that are deployed in operational contexts. Whether it possesses conceptual knowledge (Matayong & Kamil Mahmood, 2013), i.e. the kind shaped by value systems, cultural norms and reflective thinking, remains open to debate. However, as shown in cluster 5, there is growing evidence to consider GenAI outputs as functionally equivalent to actionable knowledge in practice. From this viewpoint, machines process and apply structured data and rules, much like humans apply learned frameworks and prior experience (Johnson-Laird, 1995). While the origins and meanings may differ, the outcomes are increasingly indistinguishable in operational terms, particularly in time-sensitive, data-rich environments like healthcare, finance and education.

Drawing upon this reasoning, it seems that we can now view AI output as the functional equivalent of human-produced knowledge artifacts, although it is still up to debate whether this output constitutes knowledge in an epistemological and ontological sense.

Human-machine knowledge co-creationThe dual structure of knowledge generation that emerges from this review suggests a significant theoretical shift for KM. Traditional KM models, such as the SECI model (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka & Toyama, 2003), have perceived the conversion of tacit and explicit knowledge through human socialization and reflection as the main mechanism for knowledge creation. Our findings suggest that GenAI systems are increasingly capable of engaging in parallel, machine-driven knowledge dynamics. In particular, clusters 1 and 5 illustrate how GenAI technologies can ‘autonomously’ generate context-sensitive outputs and actionable insights. This suggests that machines might no longer serve only as repositories of human knowledge (Vanitha et al., 2020) but also as actors in the knowledge creation process, by way of mechanisms that are still to be clarified. This observation resonates with, but also challenges, Nonaka’s original vision. In his early work, Nonaka explicitly acknowledged the idea that future KM systems might include non-human agents capable of generating knowledge (Nonaka & Toyama, 2003), but this idea was never formalized. The present study provides primary raw elements to begin that formalization by proposing the existence of a machine dimension in knowledge generation, one that complements but also differs fundamentally from the human knowledge spiral. Whereas in the human dimension knowledge has been seen as deeply rooted in context and social interaction, in the machine dimension it is derived from pattern recognition and algorithmic inference. Human-machine collaboration could become a new site of epistemic interaction, where GenAI-produced outputs could be triggers for new human insights, and vice versa. The implications for KM theory are extremely significant. Existing models may need to be expanded to account for synthetic externalization, the combination process facilitated by GenAI, and for hybrid socialization, human-AI interaction on collaborative platforms. In this context, organizations become not just sites for human learning but hybrid cognitive systems where GenAI tools are embedded to help humans produce knowledge.

ConclusionsOur paper is based on the idea that the advent of GenAI is causing a revolutionary shift in KM processes. To further investigate this transformation, a bibliometric literature review was conducted, analysing 1411 articles related to the topic. By providing both qualitative and quantitative insights into the role of this technology in KM, our findings provide a complete systematization of this research domain. The articles taken into consideration were classified into five distinct clusters, each representing a different aspect of GenAI applications and themes.

The results indicate a level of heterogeneity in characteristics and scope of application that is unusual for a single technology, which suggests that, even though GenAI could serve as mere support for the human knowledge creation process, it also constitutes the basis for a completely new dimension in which reality cannot be explained by relying solely on human-to-human interactions. This new dimension in the knowledge generation process, as well as the essential elements that constitute it, have been discussed here at length.

Managerial implicationsThis study presents a number of managerial implications. Considering that GenAI can be used to improve operational efficiency (Huang et al., 2023), simplify procedures, reduce costs (Pagano et al., 2023), boost creativity and foster innovation (Paananen et al., 2023), it could very fruitfully be applied in organizational contexts. Managers should evaluate integration of this powerful tool for many purposes. Firstly, as many contributions in cluster 1 suggest, GenAI can be used in synthetic dataset production to support training and simulations of diagnostic patterns, especially for managers in scarce or strictly regulated data industries such as healthcare (Eckardt et al., 2023; Khosravi et al., 2023). Secondly, as highlighted in cluster 5, managers should encourage R&D teams to integrate GenAI into early-stage innovation processes (Macedo et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024) and then apply structured validation steps, such as peer review or experimentation, to assess the value of AI-generated insights. In addition, drawing upon our study results regarding GenAI’s transformative potential in KM processes, managers should revisit their knowledge management systems (KMS) to support co-creation models where humans and machines can successfully cooperate in knowledge generation. This may involve updating internal taxonomies and retraining staff on how to critically engage with AI outputs. GenAI may also be employed to codify expert knowledge into structured outputs such as reports and learning materials (Hsu & Ching, 2023; Korzynski et al., 2023; Tlili et al., 2023). This may help preserve institutional memory and accelerate employee learning, while mitigating intergenerational knowledge gaps. Strategically integrating GenAI into KMS and innovation processes will determine an organization’s ability to remain competitive and adaptive in a rapidly evolving landscape.

As highlighted by the literature, a correct use of this technology will make the difference between previous models for learning organizations and the emerging paradigm, provided it is effectively integrated. This calls for specifically designed training courses for employees (Zheng & Stewart, 2024) that develop a culture of responsible experimentation, along with the adoption of governance frameworks that define its acceptable use in everyday tasks and processes (Ooi et al., 2023). Of course, risk mitigation strategies are also imperative (Romano et al., 2023), especially to integrate GenAI into decision-making and highly sensitive processes.

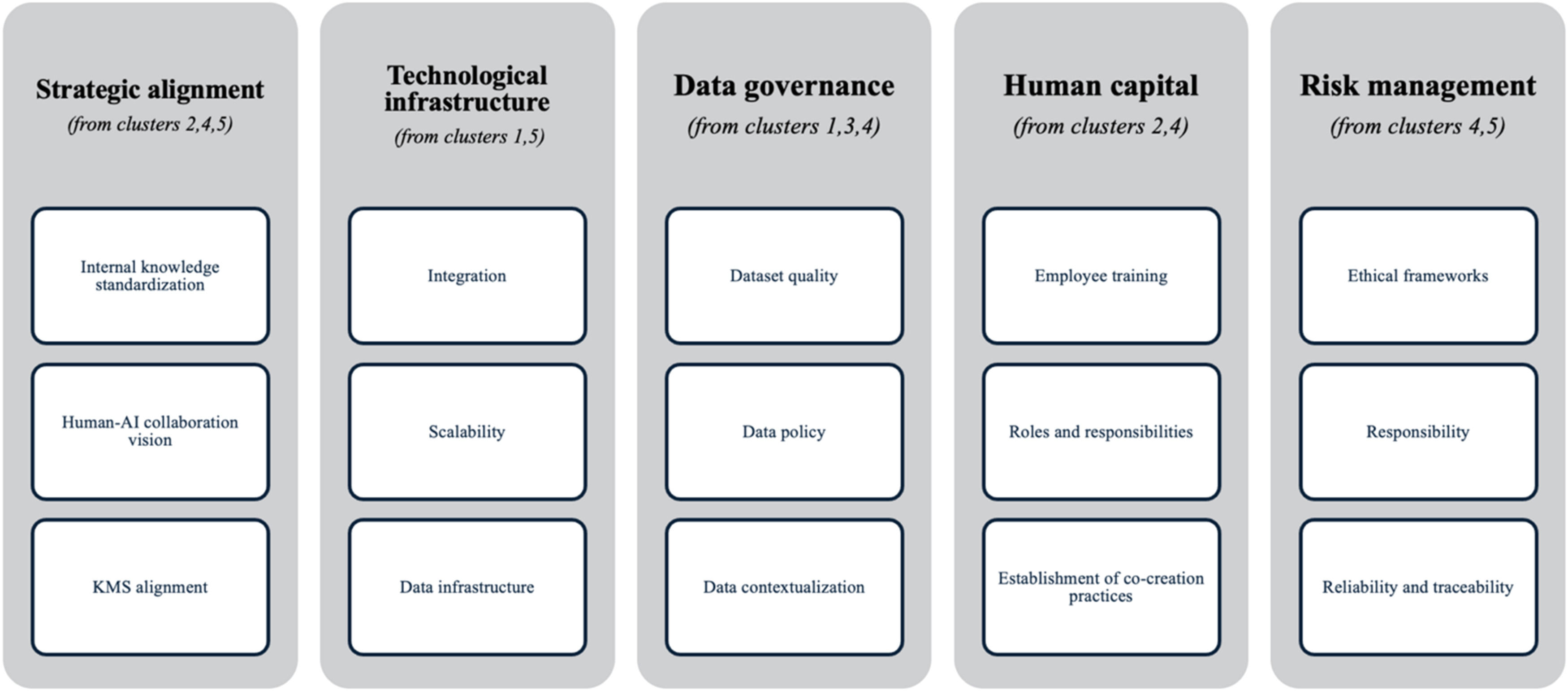

This study has provided a conceptual taxonomy derived from the thematic clusters identified in our review to systematize all the suggestions found in the literature in order to support KM professionals as they identify the main areas on which to focus in understanding their organizational readiness for GenAI integration. This taxonomy can be a managerial tool to help practitioners reflect on the key dimensions and related sub-dimensions that have emerged across the literature. Specifically, we have outlined five strategic areas, as shown in Fig. 13.

As an initial step in operationalizing the taxonomy in Fig. 13, this study has introduced the conceptual basis for a GenAI-KM readiness self-assessment tool (Table 6). This tool converts each strategic dimension and sub-dimension into targeted assessment questions that managers can use to evaluate their organization’s readiness for GenAI adoption in KM processes. By investigating each question, practitioners can identify priority improvement areas before or during implementation. For instance, an organization which evaluates itself as poor in ‘data contextualization’ may first prioritize enriching metadata and establishing consistent ontologies before piloting a GenAI-powered knowledge assistant. This approach ensures that readiness evaluation is both systematic and closely related to highly contextualized items, effectively supporting GenAI integration.

GenAI-KM readiness self-assessment tool items.

This study is one of the first contributions to critically review and systematize current knowledge in the field of GenAI research from a KM perspective. It has indicated research trends, discussed the most influential authors, countries, subject areas and journals in the contemporary GenAI research stream. It has also clearly mapped out the conceptual structure of the field by identifying five main thematic clusters.

From a theoretical standpoint, our study contribution can be seen from two different perspectives. Firstly, it has extended the theoretical traditions of the SECI model by systematically highlighting the impact of GenAI on the four SECI phases. In particular, our results emphasize how GenAI introduces new knowledge generation dynamics, such as novel GenAI-generated insights and synthetic data production, that do not map cleanly onto traditional SECI phases. To address this issue, our study has proposed a conceptual extension, namely the machine dimension, that coexists with human knowledge spirals but operates through different mechanics, suggesting a fundamental shift in KM epistemological assumptions. Furthermore, our analysis has identified the two main elements of this new dimension. Clusters 1 and 5 demonstrate how GenAI acts as both a source and synthesizer of knowledge, enabling forms of knowledge creation previously assumed to require human reasoning. These findings challenge existing theory and justify the introduction of an expanded KM framework that incorporates machine epistemic activity.

Secondly, this study has provided insights with respect to the broader development of future research directions in the field of GenAI in KM. Specifically, the most relevant future research avenues that emerge from these clusters indicate the need to investigate how GenAI-generated synthetic data affects decision-making accuracy. In addition, future research should further explore the possibility of developing user-centred explainability features specifically designed for knowledge validation and sharing in sensitive communications. Lastly, by analysing how GenAI tools can be integrated into KMSs and assessing how adequate established KM lifecycle models actually are, the importance of KM in the promising field of GenAI could be further improved. Table 7 summarizes the most significant future research directions. The first column indicates the clusters which contribute the most to addressing the issues.

Theoretical implications for future research emerging from cluster observation.