The main objective of this study was to determine which woman stereotypes are most common in a group of young adolescents from Buenos Aires; to then see how they valué these stereotypes and analyse whether they can be categorised as hostile, benevolent or of another kind. The total sample was composed of 250 secondary school students from the City of Buenos Aires, aging between 16 and 18, of both sexes. The first five woman features to come to participants minds were analysed, along with a valué scale for each of them that ranged from very positive to very negative. Additionally, levéis of ambivalent sexism were assessed in both hostile and benevolent forms. The main stereotypes of women and their positive or negative evaluation are described, along with the relationship they keep with hostile and benevolent forms of sexism. Finally, we observe that several stereotypes categorized as benevolent were valued both positively and negatively, which opens a field of discussion about the relationship between ambivalent sexism and stereotypes of women

El objetivo principal de este trabajo fue conocer cuáles son los principales estereotipos de la mujer en una muestra de jóvenes adolescentes de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, para luego indagar cuál es su valoración de tales estereotipos y analizar si los mismos pueden ser categorizados como hostiles, benevolentes o de otro tipo. Participaron del estudio 250 estudiantes de nivel secundario de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, con edades entre los 16 y 18 años, de ambos sexos. Se indagaron los cinco rasgos principales de las mujeres que más rápidamente les vinieran a la mente a los participantes, junto con una escala valorativa para cada uno de ellos cuyas opciones de respuesta iban desde muy positivo a muy negativo. Además, se evaluaron los niveles de sexismo ambivalente en sus formas hostil y benevolente. Se describen los principales estereotipos de la mujery su valoración positiva o negativa, además de las relaciones que éstos guardan con las formas hostiles y benevolentes del sexismo. Por último, se observa que varios estereotipos categorizados como benevolentes fueron valorados tanto de manera positiva como negativa, lo cual abre un campo de discusión acerca de las relaciones entre el sexismo ambivalente y los estereotipos de la mujer

Without a doubt, one of the greatest worldwide changes to characterize the twentieth century was the advance of women in social, political and economic life, gaining access to áreas that were historically denied forthem. In Argentina, it was not until 1926 that the feminist movement achieved its first great conquest in terms of civil rights, when law 11,357 repealed the Vélez Sarsfield Civil Code that gave women the status of legally incapable. Years later, with the advent of Peronism in 1946 and as a result of the social action undertaken by the Foundation headed by Eva Perón, there was a vast improvement in dignifying women's social status, giving way to professional training and education. Politically one of the principal measures was the passing of law number 13,010 that in 1947 set women's right to vote, allowing the arrival of women to Congress in the 1951 elections. The reach of this event was reflected sixty years later when in May 2007, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner became the first woman being elected president by popular vote.

Despite these progresses, in Argentina as well as in other countries, women are still subject of discrimination in different circles of social, political and economic life, such as professional and work environment (Glick, 1991; Fitzgerald & Betz, 1983), as well as individually, being the victims of various types of harassment (Gutek, 1985) and sexual violence (Unger & Crawford, 1992).

One of the main theoretical approaches in studying this phenomenon was developed by Glick and Fiske (1996, 2001), who consider sexism to have been traditionally conceived of as reflecting hostility towards women, excluding one of the phenomenon's central aspects: positive feelings towards women. This is relevant due to the fact that even though the research always emphasized man's hostility towards women, both sexes have been together from the beginning of humanity, being partners and sharing the most intimate levéis of trust. In attempting to explain this phenomenon, Glick and Fiske (1996) developed the benevolent sexism concept, defining it as a positive attitude to protect, idealise and offer affection to women, while its hostile counter part accounts for the domination and degradation of women, highlighting all behaviour that implies aggression and a disqualifying attitude.

According to the authors, both hostile and benevolent sexism imply a stereotyped conceptualization of women that restricts their field of action, even though it is often experienced as emotionally positive (for the receiver). In this sense, masculine behaviour considered to be prosocial (e.g., chivalry) and justified as of a fragüe, weak or sentimental view of women, provide examples of benevolent sexism. From a psychological perspective, thisform of sexism is not seen to be positive as it rests on trie ground of traditional woman stereotypes that support masculine dominance (e.g., the providing man -the caringwoman). In addition, its consequences are detrimental to women because if they are considered weak, fragüe or sentimental, they therefore cannot occupy leadership roles that imply being cold and tough.

As of this research, Lindsgren (1975) points out that the process of assimilating these stereotypes, defined as socially perceived cognitive schemas whose function is to process information about other subjects and the environment, takes place primordially during adolescence, considered a key stage for the structuring of interpersonal power relations (Glick & Hilt, 2000). In this sense, stereotypes not only reflect beliefs about the characteristic features of the members of a group, but further more, they contain information about other qualities such as social roles and the degree to which their members share specific characteristics, there by influencing the appearance of emotional reactions towards those who belong to a determined group (Hilton & von Hippel, 1996).

Previous research (Fernández & Coello, 2010; Lupano Perugini, & Castro Solano, 2011; Zubieta, Beramendi, Sosa, & Torres, 2011) concluded that men gather characteristics and features that stereotype them as authoritarian and leaders in general, while women tend to be restricted to the family setting, taking on roles as wives, mothers, sisters and daughters, that is to say as family members in a dependent role. Williams and Best (1990) suggest that social roles can be justified and explained by stereotypes, which correlateto personalitytraits and therefore prove very resistant to change. Furthermore, studies such as the one developed by Diaz-Loving, Rocha Sánchez and Rivera Aragón (2004), described the importance of eco-systemic and sociocultural context, aswell as specific socialization practices that transmit instrumental traits in men and expressive traits in women. What can be concluded that it is the social construction of gender and not the biological difference between the sexes that upholds the social división between men and women in modern society.

The main objective of this research was to determine which woman stereotypes are most common within a group of young students in the City of Buenos Aires; to then see how they value these stereotypes and analyse whether they can be categorised as hostile, benevolent or of another kind not meeting the inclusión criteria proposed by Glick and Fiske (1996, 2001).

MethodParticipantsParticipants wereselected by means of incidental, non probability sampling. The total sample was composed of 250 secondary school students from the City of Buenos Aires, aging between 16 and 18 (M=16.65; SD=0.66), of both sexes (men: n=108; women: n=142). Considering the ambivalent sexism levéis of the sample, men (M=30.74; SD=5.79) scored significantly higher than women (M=24.45; SD=6.22) in hostile sexism (f (249)=7.85; p<.001). Compared to the results reported in other contexts (Glick et al., 2000), hostile sexism levéis of men and women in this study are similar to those found in South Korea, Turkey and Portugal. However, they are higher than those observed in countries like Italy, Spain, Brazil, USA, Germany, England, Holland and Australia and lower than those reported in countries such as Cuba, South África, Botswana, Colombia, Nigeria and Chile. Moreover, no statistically significant differences were found between men (M=33,01; SD=4,33) and women (M=34,74; SD=6,01) in benevolent sexism levels (t (249)=-.65; p=.516). These results indícate that participants means in this study are similar to those reported in countries such as Chile, Botswana and South África, lower than those reported in Cuba and Nigeria, and higher than all other countries in which it was evaluated (e.g., EE.UU, Germany, England, Holland, Australia, Portugal, South Korea, Brazil, Spain, Italy) (Glick et al., 2000).

MeasuresSelf-report measurements were used by means of a set composed of thefollowing assessment instruments:

- •

Woman stereotypes: to assess woman stereo- types, participants were asked to write down trie five main woman features that carne to mind the quickest. The answering method was open and participants had five blank spaces to complete. They then had to classify each of these features on a valué scale that was as follows: 1=Very positive, 2=Positive, 3=Neutral, 4=Negative, 5=Very negative. According to Fiske and Glick (1995), this contrast allows one to recognise how subjects valué the object of analysis, thereby clarifying the researcher's perspective.

- •

Ambivalent sexism: to evalúate this construct we resorted to the Argentine adaptation (Etchezahar, 2013) of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) (Glick & Fiske, 1996), which has proven to be an adequate instrument to evalúate said construct in different socio- cultural contexts (Rudman & Glick, 2008). The inventory consists of 22 Ítems with a five anchor, Likert type answer system, where the subject must point out their degree of agreement-disagreement with each of the statements, ranging from 1=Completely disagree, to 5=Completely agree. The te- chñique includes items that refer to Hostile Sexísm constructs (a=.72) (e.g., The world would be a better place if women supported men more instead of criticising them; A wife should not be more successful in her career than her husband) and to Benevolent Sexism (a=.84) (e.g., Every woman should have a man to help her when she is in trouble; A man is not completely happy in life without a woman's ¡ove).

Subjects were ¡nvited to particípate voluntarily ¡n the investigaron and their ¡nformed consent was requested. Additionally they were informed that the data derived from this study would be used exclusively for scientific purposes under National Law 25.326 regarding the protection of personal information.

For the classification of women stereotypes in ambivalent sexism categories, the criterion followed was that participants should direct refer to any of the three components of its hostile (dominative paternalism, competitive gender differentiation and heterosexual hostility) or benevolent manner (protective paternalism, complementary gender differentiation and intímate heterosexuality) (Glíck & Fiske, 1996, 2001). Stereotypes that díd not meet these criteria were grouped into the category “Other” in order not to affect subsequent analyzes.

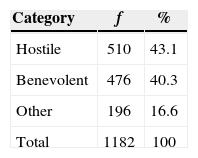

ResultsFrom the entire sample (N=250) a total of 1182 words were recorded (of whích 190 were different) to categoríse women, which were then processed by replacíng synonyms and terms with dífferent grammatical forms (gender and plural/singular forms) (Barreiro et al., in press; Sarrica, 2007). In all cases, we kepttheform with highest frequeney.

The group of words was classified according to the criteria set out by Glick and Fiske (1996, 2001) into three categories: Hostile, Benevolent and Other (this is an alternative category that included the words that did not fit the criteria proposed by the ambivalent sexism theory).Table 1 shows the summary of results.

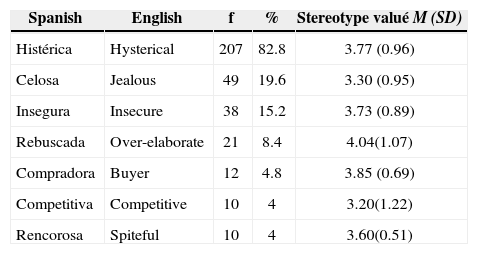

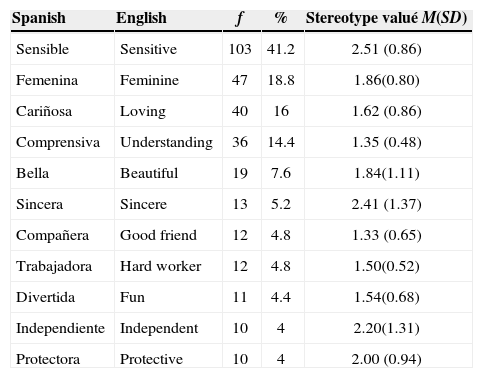

Wordswith highestfrequency accordingto their classification are presented here indicatingtheir rate of appearance, percentage and stereotype valuation:

To determine whether the hostile and benevolent woman stereotypes presented in Table 1 and Table 2 were evaluated as either positive or negative, they were firstly recategorized by the kind of sexism they represented (hostile or benevolent). Secondly its relationship with the evaluation received was analyzed by one-way ANOVA test (F(1173) =443.03; p<.001). The post hoc Tukey b contrast found three different groups (a=.05) for the relationship between stereotypes and positive and negative evaluations. The highest scores were given to the benevolent stereotypes (M=1.91; f= 476), then to the others(M=2.33; f= 196) and finally to the hostiles (M=3.74; f= 510).

Frequency of hostile woman stereotypes and average valué.

| Spanish | English | f | % | Stereotype valué M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histérica | Hysterical | 207 | 82.8 | 3.77 (0.96) |

| Celosa | Jealous | 49 | 19.6 | 3.30 (0.95) |

| Insegura | Insecure | 38 | 15.2 | 3.73 (0.89) |

| Rebuscada | Over-elaborate | 21 | 8.4 | 4.04(1.07) |

| Compradora | Buyer | 12 | 4.8 | 3.85 (0.69) |

| Competitiva | Competitive | 10 | 4 | 3.20(1.22) |

| Rencorosa | Spiteful | 10 | 4 | 3.60(0.51) |

Note: Minimum score for words was set at f≥10; Stereotype values close to 1=Very positive and 5=Very negative.

We then proceeded to analyse the relation between ambivalent sexism, in both hostile and benevolent forms, and woman stereotypes. There were no significant statistical differences in scores pertaining to benevolent sexism (t=4.62;p=.771), but differences were found in the hostile sexism scores (t(225)=-.141;p<.001), being that hostile stereotypes (M=28.96; SD=6.54) achieved a higher average than their benevolent counterparts (M=24.81; SD=6.40).

Finally, the relationships between hostile forms and stereotypes of women in men (t(100) =3.551; p=.167) and women (t(138)=.299; p=.471) were analyzed, finding no statistically significant differences. Similarly, after analyzing the relationship between benevolent forms and women stereotypes in men (t(102)=5.95; p=.094) and women (t(139)=-.387; p=.330), no statistically significant differences were found.

DiscussionThe analysed results recorded a total of 1182 words that represent the stereotypes into which the total sample (N=250) categorised women. The stereotypes were grouped as either hostile, benevolent or other, according to the theory of Ambivalent Sexism (Glick & Fiske, 1996, 2001). According tothis theory, what is most relevant is trying to pay attention to those stereotypes that appear to grant some form of psychological benefit, when in fact they represent something much more harmful (Moya, 1990). From the complete amount of words collected, 510 were categorised as hostile and 476 as benevolent (the remaining 196 were placed in the others category).

As Tables 2 and 3 shows, there are a series of stereotypes that frequently appear in their hostile and benevolent forms. In terms of the hostiles, first place is taken by the Hysterical category (f=207), far ahead from the rest, given that it was recognised by a large number of participants (82.8%). As to benevolent stereotypes, the Sensitive category carne first (f= 103) with a considerable percentage over the total sample (41.2%). Nevertheless, it is important to note that the valué placed on this stereotype was confusing, since it was considered both positively and negatively (M=2.51; SD=0.86), as was the Sincere category (M=2.41; SD=1.37) and, to a lesser degree, the Independent category (M=2.20; SD=1.31). This same phenomenon can be observed in hostile stereotypes, mainly in the Competitive category (M=3.20; SD=1.22) and, to a lesser degree, in the Jealous category (M=3.30; SD=0.95). The positive or negative valué participants place on these categories seems self-evident, they do, however, entail a certain complexity when it comes to interpreting them. An example of this can be seen in the Competitive category, since, on the one hand it can be valued as a positive stereotype set against a more submissive attitude; but it can also be viewed as a negative stereotype if taken as trying to set oneself apart while in the process putting someone else down. Likewise, it is possible to conceive of categories like Good friend (M=1.33; SD=0.65) and Understanding (M=1.35; SD=0.48) having been valued as positive due to considering women as having a different sensibility to men. Beyond the particulars of each recorded stereotype, the differences between the categories Hostile, Benevolent and Other, as well as the valué given to them, were significant, with benevolent forms achieving better valúes than hostile forms.

Frequency of benevolent woman stereotypes and average valué.

| Spanish | English | f | % | Stereotype valué M(SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensible | Sensitive | 103 | 41.2 | 2.51 (0.86) |

| Femenina | Feminine | 47 | 18.8 | 1.86(0.80) |

| Cariñosa | Loving | 40 | 16 | 1.62 (0.86) |

| Comprensiva | Understanding | 36 | 14.4 | 1.35 (0.48) |

| Bella | Beautiful | 19 | 7.6 | 1.84(1.11) |

| Sincera | Sincere | 13 | 5.2 | 2.41 (1.37) |

| Compañera | Good friend | 12 | 4.8 | 1.33 (0.65) |

| Trabajadora | Hard worker | 12 | 4.8 | 1.50(0.52) |

| Divertida | Fun | 11 | 4.4 | 1.54(0.68) |

| Independiente | Independent | 10 | 4 | 2.20(1.31) |

| Protectora | Protective | 10 | 4 | 2.00 (0.94) |

Note: Minimum score for words was set at f> 10; Stereotype valúes cióse to 1=Very positive and 5=Very negative.

Note 1: in Spanish, with minor exceptions, nouns are grammatically either feminine or masculine.

Lastly the relation between ambivalent sexism, evaluated with the ASI method, and woman stereotypes was analysed. The results show that in the case of hostile sexism there is a high degree of correlation with stereotypes considered to be hostile. This does not occur with benevolent sexism, where it does not necessarily correlate to the prevalence of benevolent stereotypes. As shown before, this difference is probably due to several stereotypes categorised as benevolent having been valued both positively and negatively (e.g., Sensitive, Sincere, Independent).

According to Hilton and Von Hippel's work (1996), woman stereotypes reflect trie social construction of gender schemas, demonstrated in the learning process of a sex's expected behaviour. Nonetheless, although to a certain degree the context prescribes which stereotypes correspond to the various roles, from the individual's perspective each construction contains an emotional aspect when it comes to assessingvalue, as related to one's life experience (Campbell, 1967). In this sense, the strategicgoal in the struggle for gender equality should not be to strive towards achieving greater equality in available resources and in the positions between the sexes, but to deconstruct the established ideological connection, in parallel with the social reconstruction of gender so as to overeóme the artificial dichotomies that lie at the foundations of the and rocentric model of masculine power. The present study points the way to further research on how woman stereotypes and the valué given them relate to ambivalent sexism. According to these results, we suggest continuing exploring this phenomenon by increasing the working sample and observing what oceurs in the adult population, seeking to confirm whether the recorded stereotypes are repeated or modified.

In addition, future work should consider the attitudinal and behavioral dimensions of the stereotypes subject in addition to the cognitive, as suggested by Eagly & Karau (2002) from the Theory of Congruence with Gender Role.

All authors contributed in all phases of the article.