Chinese students who study abroad have to face with many added life stressors compared to those who remain in China. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the use of literature is an important didactic tool in the teaching of foreign language.

This study analyzes the experience of a group of 66 Chinese university students (87.9% women, mean age=23.45 years, SD=1.303) who have come to Spain to study Spanish as Foreign Language. Well-being, life satisfaction, engagement, attitude and appreciation concerning Spanish literature were assessed quantitatively. Happiness was assessed through a qualitative approach.

Results show that student's happiness is linked to family well-being. Students were more engaged while studying in Spain. Students showed greater personal growth and independence while they were in Spain; although they had less interpersonal relationships while living in Spain. Social well-being was higher while they were in China. A relationship between attitude toward literature, engagement, satisfaction with life and psychosocial well-being was found.

The main conclusion is that well-being and happiness of Chinese students are variables that are affected by the change of country. Literature and its way of teaching have an important role in the enhancement of engagement, life satisfaction and well-being.

Los estudiantes chinos que estudian fuera afrontan estresores añadidos en comparación con aquellos que permanecen en China. Además, se ha demostrado que el uso de la literatura es una herramienta a la hora de enseñar una lengua extranjera.

El presente estudio analiza la experiencia de un grupo de 66 estudiantes universitarios chinos (87.9% mujeres, edad media = 23.45 años, DT = 1.303) que vinieron a España a estudiar español como lengua extranjera. Se evaluó el bienestar, la satisfacción vital, el engagement, y la valoración de la literatura española cuantitativamente. La felicidad se evaluó cualitativamente.

Los resultados muestran que la felicidad de los estudiantes está vinculada al bienestar familiar; tenían más engagement cuando estaban en España; mostraron más crecimiento personal e independencia cuando estaban en España; el bienestar social era mayor cuando estaban en China; se encontró relación entre la actitud hacia la literatura, el engagement, la satisfacción vital y el bienestar psicosocial.

La principal conclusión muestra que el bienestar y la felicidad de los estudiantes chinos son variables que se ven afectadas por el cambio de país. La literatura y su didáctica tienen un importante rol a la hora de promover el engagement, la satisfacción vital y el bienestar.

China's growing international role is reflected in a 23% increase in the number of students who study abroad. The Department of Education states that more than 1.4 million Chinese students studied abroad in 2011 (China Daily, 2012), nearly 7000 study in Spain from 2014 to 2015 (GB Times, 2015). This marked surge in the overseas education of Chinese students has been studied in several countries (Henze & Zhu, 2012); these studies have not focused on the measurement of positive experiences (Moores & Popadiuk, 2011). Also, the number of Chinese students who have shown an interest in the Spanish language continues to grow. Spanish, with an estimated 2000 enrolled students, is the second most studied language in China, with English being the first (Instituto Cervantes, 2012).

Chinese students who study abroad have to face with many added life stressors compared to those who remain in China (Yan & Berliner, 2013). In order to demonstrate this, Wan (2001) measured positive and negative experiences of students from China who studied abroad, finding that this group identified cultural, social, political, and linguistic differences as sources of both positive and negative experiences. This factors along with geopolitical and social-emotional variables coalesce to shape students's personal experience and self-concepts (Newsome & Cooper, 2016). O’Reilly, Ryan, and Hickey (2010) underlined that Chinese students were more prone to sociocultural imbalance and overall stress. Trice (2004) noted interactions with classmates from the foreign country as protection factors, and Yu (2016) found that integrative motivation and linguistic confidence were the strongest predictors of sociocultural and academic adaptation. Given these results, it is of utmost importance that academic institutions and instructors not only understand the customs and culture of the foreign student's home country and their language and learning style, but also promote peer support (Anderson, 2008; Salili, Chiu, & Lai, 2001).

Well-being, happiness, engagement and life satisfaction in Chinese university studentsThe model proposed by Ryff and Keyes (1995) established the multidimensionality of well-being. Research has proven that students who engage themselves with their own culture in the same way that they apply themselves to learning a new one have a greater probability of finding social support. This is related to self-sufficiency, the achievement of goals, and a greater mastery of their environment (Hui, Lent, & Miller, 2013).

For Chinese people, interpersonal support (including that from spouses, parents, friends, neighbors, and colleagues) and support utilization were significant predictors of happiness (Liping, 2001). In Chinese students, subjective well-being comes from life satisfaction, positive feelings, social support, and an orientation toward human values (Biao-Bin, Xue, & Qiu, 2003). Zhi (2007) found that interpersonal and romantic relationships, academic pressure, future work prospects, personal finances, expectations, personal values, and personality influence the well-being of these students. Personal values can add to providing meaning in life, and thus serve as predictors of well-being (Zhang et al., 2013). After analyzing happiness, Lu (2001) concludes that for Chinese university students, happiness is defined as a state of mental satisfaction characterized by positive emotions in which needs are being met. According to this author, harmony is achieved when goals are reached and one lives freely and has hope about the future. Finally, he states that happiness can be reached through discovery, gratitude, altruism, and self-knowledge.

On the other hand, engagement is linked to academic performance and self-sufficiency (Llorens, Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2007; Schaufeli, Martínez, Marques, Salanova, & Bakker, 2002). Students who have parents with a college degree are generally more motivated than their peers (Pike & Kuh, 2005). Engagement is related to higher levels of subjective well-being (Schueller & Seligman, 2010) and life satisfaction (Peterson, Park, & Seligman, 2005). It is also related to a well-adjusted university life, increased psychosocial competence, practice, development, and well-being (Torres, Howard-Hamilton, & Cooper, 2003). Determination, which is an aspect of engagement, is related to academic achievement (Schaufeli et al., 2002).

Professor's attitude may influence students’ learning in a way such a professors with higher engagement motivate and generate more life satisfaction in students (Küster & Vila, 2012).

The use of literature in the promotion of psychological and social well-being of studentsSuccess in learning a new language depends on the motivation of a student (Wong, Chai, Chen, & Chin, 2013). This complex variable is used to explain individual differences in the learning of a new language (MacIntyre, MacMaster, & Baker, 2001). According to Yu (2012), it is important to promote the study of the classics, as well as to encourage writing in order to improve communication. The use of literature is an important didactic tool in the teaching of foreign language (Albadalejo, 2006).

Using literature to explain the meaning of passages, especially when related to irony and humor, serves to introduce sociocultural, pragmalinguistic and literary aspects of those texts (Villarrubia, 2010).

The present studyThe results of previous studies show that there might be changes in different variables related to the well-being and the academic performance. In addition, the present study shows that there may be a role of literature and its pedagogy of Chinese students’ well-being and motivation.

The present study aims to analyze the well-being, happiness, life satisfaction, and engagement of Chinese students who came to Spain to study Spanish, to compare their standard of living in Spain with which their well-being, happiness, life satisfaction, engagement, they had in China and to study the role of literature in the well-being of students. Both quantitative and qualitative approaches were applied. Furthermore, we analyzed the relationship between attitudes and emotions concerning literature studied in class and engagement, psychosocial well-being and satisfaction with life.

Findings of this study offer several important contributions. Firstly, this study examines an understudied population: Chinese students who came to Spain in order to learn Spanish. Secondly, it examines variables that were not analyzed in other studies (i.e. Newsome & Cooper, 2016; Yan & Berliner, 2013): students’ well-being, happiness, life satisfaction and engagement. In addition, this study examines whether there are changes in these variables related to moving to a different country and the use of literature as a tool for the well-being improvement and the involvement of students while learning Spanish. In addition, a mixed quantitative and qualitative approach was applied in order to study not only the consistency between the two approaches, but also as a starting point to develop further knowledge on students’ well-being (Plasencia, 2016).

MethodParticipantsThe sample consisted on 66 Chinese students, who at the time of the evaluation were taking a class on Spanish literature within a master's program at a Spanish University. Of those who participated, 87.9% were women, the mean age was 23.45 years (SD=1.303), and 86.4% of the participants were only-children, that is, they had neither brothers nor sisters. Within this group, 50% grew up in a household with college-educated parents. While English is the first foreign language that they learned, 86.4% of the participants noted Spanish as their second foreign language. Over 85% of participants have lived in Spain at least 3 months.

MeasuresQuestionnaire of sociodemographic variables and student happiness: This questionnaire was designed specifically for this investigation. It is comprised of 16 questions, 8 of which are open-ended. The variables used are gender, age, only-child status, college-educated parents, if Spanish was their first choice as a college major, if 2012 was the first year that they visited Europe, their reasons for going to college, interest in Spain and Spanish culture, if they regretted their decision to study in Spain, if they believed they would find a job after completing their studies, and if they would recommend others to study Spanish literature in the way it had been presented to them. The students were asked if they had been emotionally moved while studying literature and if they considered themselves happy. Finally they were requested to provide their definition of happiness.

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS, Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). It is a one-dimensional measurement of the 5 items by which people indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with a 7-point Likert scale. This scale has been validated in Chinese population (Sachs, 2003; Wu & Yao, 2006). Psychometric properties for the present study are detailed as Supplementary Table 1.

Questionnaire about attitudes and emotions concerning literature studied in class: This questionnaire was designed for this investigation. It consists of 15 items on a scale much like the Likert, 7-point scale, which evaluates various elements related to the literature studied in class. Psychometric properties are presented as Supplementary Table 2.

Utrecht engagement scale for students-reduced (UWES-9, Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003): This questionnaire evaluates the engagement of college students. It consists of 9 items, in which three components of engagement are analyzed: determination, dedication, and absorption. All of the items follow the Likert 7-point model; going from 0 (never) until the 6 (always). This scale has been validated in Chinese population (Fong & Ng, 2011; Yi-wen & Yi-qun, 2005). Psychometric properties for the present study are detailed as Supplementary Table 3.

Esthetic experience/esthetic pleasure while reading a literary work: This scale was adapted by taking the base definition and components of the Appreciation of beauty as a character strength, considered by the Values In Action perspective (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). It is a questionnaire comprised of 10 items following the Likert 5-point scale. The total score is the sum of all of the items. The internal consistency of this scale is .85. Psychometric properties are presented as Supplementary Table 4.

Scale of psychological well-being, reduced version (SPWB; Ryff, 1989; Spanish version of Díaz et al., 2006): This consists of 29 items based on the six facets of well-being: self acceptance, positive relationships, a purpose driven life, independence, environmental mastery, and personal growth. The items are formulated on a Likert 6-point scale and have a range of options between 9 (completely disagree) and 6 (completely agree). The authors of the translation found that the reliability of internal consistency obtained by the instrument is: .83 (self-acceptance); .81 (positive relationships); .73 (independence); .71 (mastery of surroundings); .83 (a purpose driven life) and .68 (personal growth) (Díaz et al., 2006). This scale has been validated for Chinese population (Li, 2014). The study has taken into account the psychological well-being of the students while students were living in China and in Spain. Psychometric properties for the present study are detailed as Supplementary Table 5.

Social Well-being Scale (Keyes, 1998, Spanish version by Blanco & Díaz, 2005): Evaluates social well-being through the five pillars proposed by Keyes (1998). It consists of 23 items formulated on a scale that follows the Likert 6-point model. It has a range of options between 1 (completely disagree) and 6 (completely agree). Five different scores are calculated; one for each evaluated facet and a median average of the corresponding items. The reliability of each of the scales is: social integration (.69), social acceptance (.83), social contribution (.70), social updating (.79) and social coherence (.68). Psychometric properties for the present study are detailed as Supplementary Table 6.

All measures in its Spanish version are presented in Supplementary Material 2.

ProcedureStudents were asked if they would like the questionnaires translated into Chinese. All of the students were in favor of a Spanish-only questionnaire. The forms, which are included all questionnaires presented as Supplementary Material 2, were distributed in class. Students were given instructions concerning the completion of the questionnaire, as well as a description of the goals of the study. Students completed the questionnaires during their free time, and were asked to turn them in the following week. Out of a total of 75 students enrolled in the class, 66 questionnaires were turned in. There were no questionnaires invalidated by anomalous responses.

Data analysisThe data collected from each questionnaire was codified and mechanized using statistical software SPSS for Windows (IBM, 2012) version 21. The tests computed were t test for related samples, McNemar's test, Pearson and Spearman's correlation coefficients. When significant results were found, effect size was computed: Cohen's d for t test, and the intensity of Pearson's correlations were used as an indicator of effect size. As a rule of thumb (see Cohen, 1992), values for small, medium, and large effects are:

Small: .20<d<.50; .10<r<.30.

Medium: .50<d<.80; .30<r<.50.

Large: d>.80; r>.50.

The level of significance used for all tests was α=.05.

On the other hand, qualitative analysis consisted on analyzing similarities and differences between responses given by the students to all of the open-ended questions (see Supplementary Material 2). Examples taken verbatim from the questionnaires were also used. These similarities were compiled by two independent coders, reaching a Cohen's kappa coefficient equal to .98. In the results section, percentages and significant examples of each of the categories are offered.

ResultsMotivations concerning the study of Spanish by Chinese studentsThe main reasons why students opted to pursue a college education were grouped based on their answers to the question: “Why do you go to college/university?” Most of the participants (47%) decided to attend college as a personal choice. The second and third ranked motivations to go to college were described as personal choices and in order to please their family (39%) and related to the job market (8%). Students cited both finding a job in the future and improving their current work options. A mere 4% cited pleasing their family as the main motivation to pursue higher education. The category, “other motives” (2%), encompassed those motivations that did not fit into the established sets.

The students were asked if while in China, their first choice for an academic concentration was Spanish. Over half of them (54.5%) explained that Spanish was indeed their first choice and 45.5% had been more interested in other majors. Among the most popular were technology-based majors, and especially computer science.

Regardless of this result, when asked about their interest in Spain and Spanish culture, 93.6% of the participants shared that they had a desire to study Spanish culture when they were in China. More than a half of students (51.28%) were interested in Spanish culture while studying in China. The relationship between students’ interest in Spanish culture before and after studying in Spain was significant (χMcNemar2=4.27, p<.05).

The following section reproduces reasons cited in the questionnaires: “When I studied Spanish in college I knew a lot about Spain: flamenco, sports, movies…”; “in my imagination, Spain is very romantic and passionate. I want to get to know another culture; I’m interested in learning Spanish”. Participants also stated that their interest in Spain stemmed from the success of Spanish sport teams (15.38%): “I’m interested in studying Spanish because I’m interested in formula 1 and I like Alonso. I want to learn the language he speaks”; “Soccer is very famous in the world”. Students were also drawn to Spain because of their eagerness to learn another language (12.82%): “I have chosen to study Spanish because I wanted to learn a language different language apart from English”. As can be seen in the following remark, students (5.13%) also chose to study Spanish in order to open themselves to new experiences and have freedom: “I was moved by the spirit of freedom that I read in the books of the Taiwanese author, San Mao”. Out of those queried, 7.69% cited other motives. For example: “My personality is quite Spanish. Many people have said this to me”.

A total of 80.9% of the participants explained that they continued to be interested in Spanish culture after having studied in Spain. The main motive why 33.33% students continued to be interested in Spain was the inner interest which Spanish has as a culture. Two examples of such answers are: “Of course I’ll continue to be interested in Spanish culture after I leave. I’m going to look for a job that is related to Spanish or to Spain. It is therefore very important that I get to know the country”; “I’ll continue to be interested in Spanish culture because now I know the history of Spain and what intellectuals have had to do in the past in order to defend the spirit of freedom”. Others (21.21%) cited Spanish as their motive: “I’ll continue to be interested in Spanish culture because I love Spanish and everything related to it”; “My interest in the language prompted me to start studying it five years ago”. Another 15.15% pointed toward literature as motive for their continued interest in Spanish culture: “After having read many works of literature, I am much more familiar with Spanish culture and her great authors. I will continue to read Spanish literature”; “I have learned about Spanish culture through literature and I’ll keep learning from Spanish literature”. For 15.15% the experience of living in Spain will continue to fuel their interest in Spanish literature: “I had a chance to live and study here”; “yes, because I like life here and I’m quite used to it. Art, activities, exhibits, and nightlife all add to Spanish culture. Although Spain is in crisis, Madrid continues to be an attractive city to me”. A mere 6.06% cited differences between Spain and China as motivation. For example: “Since Spanish culture is so different from Chinese […] it seems interesting to me, but also very hard to understand”. The remaining 9.09% offered reasons that cannot be grouped with the rest. For example: “In order to be a Spanish teacher, I need to know Spanish culture”.

Within the analysis concerning motivations related to studying Spanish, the students were asked if a Masters in Spanish language would guarantee them a job in China. There was an affirmative response from 63.6%.

Happiness and psychosocial state of these Chinese studentsAccording to 51.28% of the students, happiness is related to the health and well-being of their loved ones (friends and family). Two examples of these definitions are: “Happiness for me has to do with the health of my family, my parents, my boyfriend, and my boyfriend's family. If they are happy and healthy, I am also happy”; “…my whole family is healthy and my friends and me can reach our life goals”; “For me, the most important thing is the happiness of my family”. Happiness was linked to academic and work-related success by 15.38% of the participants. The following are examples that stand out from this grouping: “Happiness comes from doing things well and achieving success”; “Happiness comes from having a good life, getting a good education, having a job you like, and when your family is healthy”. Contributing to society was cited as a definition of happiness by 7.69% of the participants. As one student explains: “It is very easy for me […] I want my job to contribute to society. It's better not to ask for more, because you risk being unhappy”. Knowledge was the answer of 5.12% of the students: “Traveling and getting to know many cultures”. Of the definitions given, 12.82% did not fall within the other groupings. The following is a small sample of those definitions: “To be happier than others. Yet, I know that this is a paradox and that I will never be happy if I try to be happier than everyone else”; “There are many things in Spain that make me happy, like the food and some Spanish friends”.

Students were asked if they were happy when they were studying in China and also while studying in Spain. They were then asked to evaluate why they considered themselves to be happy. Of the participants, 87.2% explained that they were happy as students in China, while 72.3% continued to be happy in Spain. This relationship was non-significant (χMcNemar2=1.71, p>.05), so happiness levels were the same.

Of the queried, 80.64% explained that they felt happier in China because they were with their family. The following are a few examples: “Because my family is very important to me. When I am with them I can share my life with them and bring them joy”; “Because I really like my family. I am very fortunate to belong to this family, and my grandparents, aunts, and uncles always have interesting stories to tell”. In this same way, the main source of unhappiness in China is also related to family dynamics: “Because my parents have helped me too much and this is not good for me in terms of independence, but I can’t change that”; “Yes, like the first line of Tolstoy's Ana Karenina: All happy families are alike. No. Intergenerational conflict is both a classic and current theme”; “Because there is very little time to spend together. My parents are very busy, but, of course, they are working for me, and I thank them for it”.

Of the students, 36.66% think that they are happy in Spain because they are studying something that they like. Examples of this are: “Yes, because I have studied many things at the University that are useful”; “Because after this year I will have a master's degree and I can find a job as a teacher in China”. The independence that they have gained from living in Spain is the reason for happiness cited by 26.66% of the students: “I consider that I am happier than ever because I feel quite free and I can live my life as I wish”. The main reason for unhappiness in Spain has to do with feeling unsafe: “Because my purse was stolen on Diego de León Street. Now I don’t have a passport, a residency card, or a student identification card. I can’t travel and I can’t leave. I can’t do anything. Why do thieves do this to foreigners?”; “I was robbed at Ikea last year. The situation is unsafe”. Almost all of the students (91.5%) expressed no regret about having come to Spain to study Spanish.

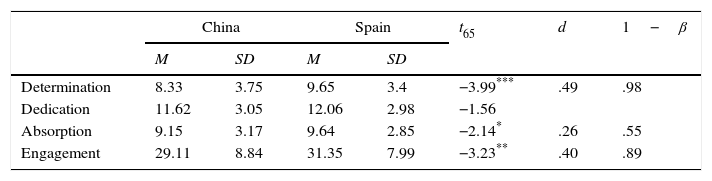

Students’ engagementThe results for the t test paired matches about the difference in engagement while the students were in China and while in Spain are reflected in Table 1.

Results of t-test and descriptive statistics for engagement scale.

| China | Spain | t65 | d | 1−β | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Determination | 8.33 | 3.75 | 9.65 | 3.4 | −3.99*** | .49 | .98 |

| Dedication | 11.62 | 3.05 | 12.06 | 2.98 | −1.56 | ||

| Absorption | 9.15 | 3.17 | 9.64 | 2.85 | −2.14* | .26 | .55 |

| Engagement | 29.11 | 8.84 | 31.35 | 7.99 | −3.23** | .40 | .89 |

Notes: n=66; M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation; d: effect size; 1−β: power test.

There were significant statistical differences between the students’ lives in China and during their stay in Spain. The numbers are the following: determination (t65=−3.99, p<.001; d=.49, 1−β=.98); absorption (t65=−2.14, p<.05; d=.26, 1−β=.55) and considering all of the participants’ engagement total score (t65=−3.23, p<.01; d=.4, 1−β=.89) having the greatest score when the students were in Spain. The difference in dedication (t65=−1.56, p>.05) was not statistically significant.

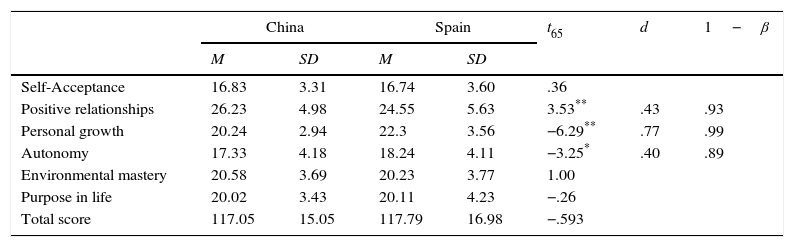

Student's life satisfaction and well-beingTable 2 shows the descriptive statistics and the results of the t-test for different aspects of psychological well-being, comparing the students when they were in China and while in Spain.

Results of t-test and descriptive statistics for psychological well-being scale.

| China | Spain | t65 | d | 1−β | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Self-Acceptance | 16.83 | 3.31 | 16.74 | 3.60 | .36 | ||

| Positive relationships | 26.23 | 4.98 | 24.55 | 5.63 | 3.53** | .43 | .93 |

| Personal growth | 20.24 | 2.94 | 22.3 | 3.56 | −6.29** | .77 | .99 |

| Autonomy | 17.33 | 4.18 | 18.24 | 4.11 | −3.25* | .40 | .89 |

| Environmental mastery | 20.58 | 3.69 | 20.23 | 3.77 | 1.00 | ||

| Purpose in life | 20.02 | 3.43 | 20.11 | 4.23 | −.26 | ||

| Total score | 117.05 | 15.05 | 117.79 | 16.98 | −.593 | ||

Notes: n=66; M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation; d: effect size; 1−β: power test.

There were significant differences in Positive relationships (t65=3.53, p<.001; d=.43, 1−β=.93), Personal growth (t65=−6.29, p<.001; d=.77, 1−β=.99) and Autonomy (t65=−3.25, p<.01; d=.4, 1−β=.89), students had higher scores in Positive relationships when they were studying in China, and related to Personal Growth and Autonomy, students’ scores were higher when they were studying in Spain. The rest of the differences were not statistically significant.

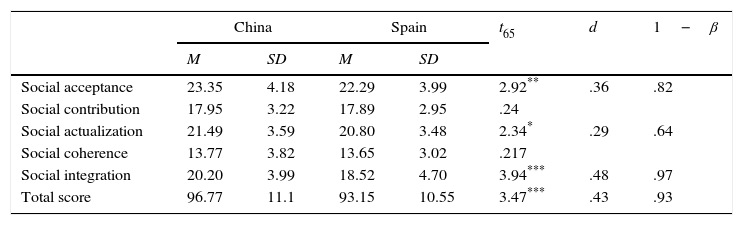

The descriptive statistics and the results of the t-test comparing the social well-being of the students when they were in China and while in Spain are reported in Table 3.

Results of t-test and descriptive statistics for social well-being scale.

| China | Spain | t65 | d | 1−β | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Social acceptance | 23.35 | 4.18 | 22.29 | 3.99 | 2.92** | .36 | .82 |

| Social contribution | 17.95 | 3.22 | 17.89 | 2.95 | .24 | ||

| Social actualization | 21.49 | 3.59 | 20.80 | 3.48 | 2.34* | .29 | .64 |

| Social coherence | 13.77 | 3.82 | 13.65 | 3.02 | .217 | ||

| Social integration | 20.20 | 3.99 | 18.52 | 4.70 | 3.94*** | .48 | .97 |

| Total score | 96.77 | 11.1 | 93.15 | 10.55 | 3.47*** | .43 | .93 |

Notes: n=66; M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation; d: effect size; 1−β: power test.

There are significant differences in Social acceptance (t65=2.92, p<.01; d=.36, 1−β=.82), Social actualization (t65=2.34, p<.05; d=.29, 1−β=.64), Social integration (t65=3.94, p<.001; d=.48, 1−β=.97), and in general Social well-being (t65=3.47, p<.001; d=.43, 1−β=.93). All scores were higher when students were studying in China. The differences in Social acceptance and Social Coherence were not statistically relevant.

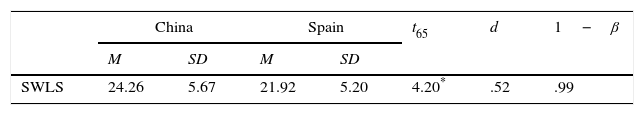

Table 4 shows the results of the analysis of differences in life satisfaction.

Results of t-test and descriptive statistics for satisfaction with life scale (SWLS).

| China | Spain | t65 | d | 1−β | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| SWLS | 24.26 | 5.67 | 21.92 | 5.20 | 4.20* | .52 | .99 |

Notes: n=66; M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation; d: effect size; 1−β: power test.

There were differences in life satisfaction between students when they were in China and while in Spain (t65=4.2, p<.001; d=.52, 1−β=.99).

Literature as a tool to promote well-being, engagement, and life satisfaction of students

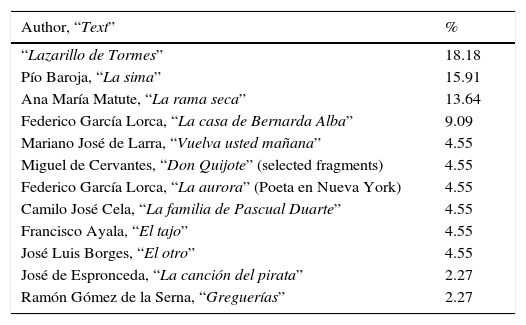

Qualitative analysisWhen the students were asked if they were moved by the literary analyses performed during the course of the class, 76.6% of the participants answered affirmatively. The literary texts that most moved them are listed in Table 5.

Literary texts chosen by the students.

| Author, “Text” | % |

|---|---|

| “Lazarillo de Tormes” | 18.18 |

| Pío Baroja, “La sima” | 15.91 |

| Ana María Matute, “La rama seca” | 13.64 |

| Federico García Lorca, “La casa de Bernarda Alba” | 9.09 |

| Mariano José de Larra, “Vuelva usted mañana” | 4.55 |

| Miguel de Cervantes, “Don Quijote” (selected fragments) | 4.55 |

| Federico García Lorca, “La aurora” (Poeta en Nueva York) | 4.55 |

| Camilo José Cela, “La familia de Pascual Duarte” | 4.55 |

| Francisco Ayala, “El tajo” | 4.55 |

| José Luis Borges, “El otro” | 4.55 |

| José de Espronceda, “La canción del pirata” | 2.27 |

| Ramón Gómez de la Serna, “Greguerías” | 2.27 |

A 29.1% of the students were mainly moved, by literature because of the feelings elicited by the text: “I am touched by the profound nature of the literature taught in class. I think that literature is a treasure for all human beings”; “Because of the explanations of the professor I am better able to understand the feeling and the emotions expressed in poetry”. The social context of the text moved 23.52% of the students: “It is related to Spanish history. Lazarillo is a poor boy that serves many masters. He is a son of nothing. This reflects Spanish social classes in that period. The people are cold and inflexible. I feel sorry for Lazarillo”; “It is a fantastic text and I like texts that use literature in order to show reality.” An interest for the texts was listed as the reason 23.52% of the students were moved by the literature studied: “Because when I read it for the first time I didn’t find much that was interesting, but the explanations of the Professor made me want to read the text again”; “Because I like the theme of human deficiency in La Sima and of dictatorship in the Casa de Bernarda Alba”. The remaining 11.76% of the reasons could not be grouped with the others. An example of this type of answer is: “Because I have translated it into Chinese and I like this”. A vast majority of the students (80.9%) would recommend studying Spanish literature in the same way used to teach them.

Half of the students (56.52%) recommended studying Spanish literature following the didactic approach used in class because of the interest that the literature triggers: “This method is interesting and I really learned something. In literature class in China, we only memorize the author, their published work, and dates. It is useless and boring.” “This way of teaching has awakened my interest for literature”; “because this elicits more interest in literature. Now that we are able to locate clever details in the text, we want to continue analyzing”. According to 21.74% of the participants, the way that the class was taught facilitates learning the specifics of the text, and they would recommend this style of teaching in the future: “I really liked the structure of the class. First we are given an initial concept and then we study the texts from each time period. When we study the texts we focus more on their meaning and what the author is expressing with his or her words. Sometimes we are moved by the texts”; “With this way of teaching we can learn more profoundly about the novels”.

Another 8.7% recommended this manner of teaching because it opens up the mind: “It is much better that the traditional teaching philosophy of my university. This style has opened my mind and inspired me”. The remaining 13.04% of the participants provided answers that could not be grouped with the rest. For example: “Because it will help them to learn the language and the culture”. Some examples of reasons given not to use this teaching philosophy are: “So they don’t think I’m a snob”; “because the majority of my classmates are lazy and if they are not taking exams they are not going to think about and read literature, especially the longer texts.”; “because I don’t think that Spanish literature is going to be of much help in any other job, if I am not a Spanish teacher in the future. It's easy to forget what we have learned in class if we don’t go over it at home.” In general, the reasons why this teaching style would not be recommended have less to do with the class that they took than the way the students judge their peers and with a future labor market.

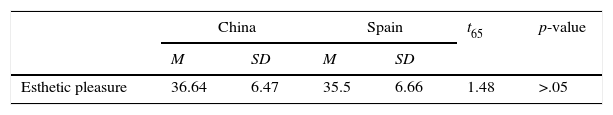

Quantitative analysisTable 6 shows statistics concerning the scale of esthetic pleasure linked to literature. Although the median of these results is slightly higher when the students are in Spain, this difference is not significant (t65=1.48, p>.05).

The minimum value of this scale is 10 and the maximum is 50. Keeping this in mind, we can see that the students generally place themselves within higher ranges when asked about esthetic pleasure linked to literature.

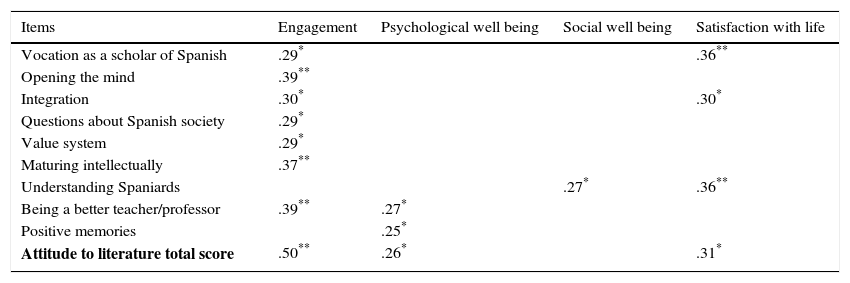

The Spearman and the Pearson correlations for the total score of the scale and the other factors has been calculated in order to evaluate the relationship between the items of the esthetic pleasure scale and the scores of overall engagement, life satisfaction, psychological and social well-being (see Table 7).

Correlations between items and scales.

| Items | Engagement | Psychological well being | Social well being | Satisfaction with life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vocation as a scholar of Spanish | .29* | .36** | ||

| Opening the mind | .39** | |||

| Integration | .30* | .30* | ||

| Questions about Spanish society | .29* | |||

| Value system | .29* | |||

| Maturing intellectually | .37** | |||

| Understanding Spaniards | .27* | .36** | ||

| Being a better teacher/professor | .39** | .27* | ||

| Positive memories | .25* | |||

| Attitude to literature total score | .50** | .26* | .31* |

Notes: n=66; Bold letters: Pearson's correlation computed; only significant items were included, full information is available under request.

The analysis shows that the items that measure the calling to be a scholar of Spanish studies, speaking positively about the experience, opening the mind, integration, and questions about Spanish society, the value system, intellectual maturity, being a better teacher/professor, and positive memories of the experience were linked to engagement, psychological well-being, social well-being, and satisfaction with life. The rest of the items did not have a significant relationship with the variables being studied.

DiscussionThis study analyzed life satisfaction, psychosocial well-being, happiness, and engagement as well as how literature influenced these variables, within a group of Chinese students when they were studying in China and while in Spain. Furthermore, it also studied interest in Spanish culture and the motives that fueled this interest after having studied in Spain. It is a pilot experience that that brings together various lines of work: positive psychology, psychology of well-being, psychology of education, and teaching philosophy of literature. A quantitative evaluation of the variables was applied and the students’ experience was analyzed qualitatively. Many of the students who participated chose to study Spanish in Spain for personal reasons, such as pleasing their family. These results are congruent with those found by Kim and Gasman (2011), who concluded that the opinion of family and friends is important when making the final decision about choosing a university and a major. The study shows that engagement is greater when students studied Spanish literature in Spain. This is compatible with the interest shown by the students to keep learning in spite of the difficulties of the texts, and to continue reading the classics even after class had ended. Life satisfaction and social well-being (including levels of social contribution and social actualization) were greater when the students were in China. These results can mainly be explained through an association with the family, since students generally link happiness with family well-being and considered that they were happy in China because of proximity to their family. Given that most students linked happiness to success, the factors of happiness for university students proposed by Lu (2001) are partially confirmed in this investigation. With respects to psychological well-being, students showed greater autonomy and personal growth, but less positive relationships while in Spain than when they were in China. These results are compatible with the qualitative information given by the students. The students have expressed that although they miss their friends and family in China, the experience of living in Spain has made them more independent and possess a greater sense of freedom. Overall, the student questionnaires showed that attitudes toward literature were related to a greater engagement, especially concerning integration into Spanish society and matters having to do with Spain, the student's value system and increased intellectual maturity. These connections, as well as the correlation between psychological well-being and attitudes toward literature, are of medium intensity. Social well-being is related to some of the variables concerning attitude toward literature. These results are compatible with those proposed by Hui et al. (2013), who claim that learning a new language promotes student integration and social well-being. The items concerning positive speech and opening the mind can be read as contradictory, since they have a negative relationship with social well-being. These results may be attributed to the emotion caused by speaking about literature. This conclusion was confirmed using the qualitative information provided by the students. The results concerning attitudes toward literature and other variables of well-being highlight the importance of literature as a didactic tool that affects well-being and satisfaction, and serves to inspire students (Albadalejo, 2006; Musaio, 2012). The literary course was designed to provide students with an opportunity to come into close contact with great writing and make the classics resonate with modern – and in this case second or third language – readers. Literature was used as a tool to provide the students with new possibilities for intellectual and esthetic fulfillment. Through close reading, the professors aimed to promote critical thinking and creativity as well as greater understanding of Spanish language, culture, and general society. The readings were presented within a cultural and historical frame. Ocasar (2009) has shown that using a historical approach has great didactic potential. With a few exceptions, (Borges, Rulfo and Cortázar), the texts studied belonged to the Spanish Cannon and reflected literature from the Middle Ages until the modern age. It is notable that the texts that most captivated the students, like Lazarillo de Tormes, Pío Baroja‘s “La sima” and Ana María Matute's “La rama seca,” all deal with marginalized characters that are mistreated by society. Furthermore, although the three texts represent disparate time periods and genres, all three have a child protagonist who suffers from considerable poverty. The study shows that the theme of a vulnerable being and their struggle for survival within a hostile society has both moved and interested the students. The results of this study suggest that contemporary literature should not necessarily be privileged over classic literature in classes of Spanish as a foreign language. The participants’ answers evidence that once the deeper significance of the classics -even those written 500 years ago, such as the mid -sixteenth century picaresque novel, Lazarillo de Tormes- has been unraveled, they have the potential to be more current and modern than many twenty-first century texts (Serrano, 2005). The research underlines the importance of using literature in classes of Spanish second language acquisition (SLA) and also in the academic preparation of instructors of SLA. Until now studies have emphasized the importance of teaching literature as a means to widen the scope of linguistic knowledge (Acquaroni, 2007; Montesa & Garrido, 1990). This investigation introduced more variables associated with psychology and their analysis supposes underlining the importance of teaching literature within language courses. The query demonstrates that it promotes motivation and inspires students, as well as increasing the well-being psychological and social well-being of the student that is moved while studying a foreign language.

The main limitations of this study lie in the very essence of a pilot experience. This means that it is assumed that the sample is incidental and that the results must be studied with caution. The evaluation of happiness was qualitative, which makes it difficult to compare happiness while in China and in Spain. The use of quantitative measures of the degree and level of happiness (for example the Happiness Questionnaire by Fordyce, 1988; or the Subjective Happiness Scale by Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999), will provide future perspectives concerning its fluctuation during both time periods. Furthermore, the impossibility of contacting the students before coming to Spain, the assessment of the variables of interest when they were in China was after they had left the country. This may have caused biases that should be taken into account. An ongoing study would aim to analyze differences between students who see a future career in Spanish and others who do not, as well as an analysis of personal values that investigates the influence of literature in the knowledge of the scale of these values. Moving forward, as a project's aim, it would be interesting to measure appreciation of beauty as one of the main pillars of the VIA model of personal strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Ovejero, 2015). Future research should focus on the multiple benefits that esthetic fulfillment provides and specially examine its relationship to literary texts.

The main conclusion of this study is related to the importance of assessing and taking into account students’ well-being when studying in a different country since there might be significant changes in areas different of their academic performance, for example, their social support. For these students, studying abroad involves, generally, an experience that brings autonomy and personal growth, playing literature and pedagogy an important role in students’ motivation levels in order to learn a new language. However, a decrease occurs in some variables, particularly those related to the social well-being. These results should be considered since they underpin the idea of implementing intervention programs in order to promote the contact between foreign and domestic students, since interactions with classmates from the foreign country are protection factors (Trice, 2004; Yu, 2016).

Authors’ contributionAuthors contributed in the following way: MOB developed the protocol of administered questionnaires, performed the data analysis and drafted the results section. SLR participated in data collection, drafting of the introduction and discussion of the manuscript. GG participated in the collection of data and in the translation of the manuscript into English. All authors contributed to the review of the manuscript.

Peer review under the responsibility of Asociación Mexicana de Comportamiento y Salud.