Cardiac interoception exhibits tight coupling with brain activity, deeply engaging in emotional behavior. However, the neural mechanisms underlying how heart activity influences brain emotional processing remain poorly understood. This study introduced the heartbeat oscillatory potential (HOP), a novel EEG-based index time-locked to ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, and examined the change of HOP during 0.1 Hz slow-paced breathing (SPB). Resting-state data from 108 healthy adults revealed that HOP was involved in the frontal and parietal cortices. Data collected from 37 subjects showed that SPB increased HOP in a spatial- and phase-dependent manner, with increased HOP in the right prefrontal cortex around the peak of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, mediated the association between the heartbeat oscillations and enhanced emotional control. These findings underscore the pivotal role of the right prefrontal cortex in linking cardiac interoception, providing insights into the benefits of SPB on emotional control from a heart-brain interaction perspective.

Body rhythms that continuously and cyclically interplay with the brain have attracted increasing scientific interest, emerging as a burgeoning field of research. The neurodynamics of heart-brain interactions, particularly the integration of cardiac interoceptive signals within the brain, play a critical role in the making of emotions (Greenwood & Garfinkel, 2025). However, the mechanisms underlying how heart-brain interactions influence emotions require further investigation.

Heart rate variability (HRV) describes the fluctuations of heart activity over time, reflecting both the descending brain-to-heart control and the ascending regulation of heart-to-brain (Bates et al., 2022). The high-frequency component of HRV (HF-HRV, 0.15–0.4 Hz) is regarded as cardiac vagal activity (Valenza et al., 2019). The low-frequency component of HRV (LF-HRV, 0.04–0.15 Hz) may represent the mixture of sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow, which remains debated. In particular, the LF component with a dominant frequency of approximately 0.1 Hz characterizes a fundamental heart-brain circuit, supporting the vagal-mediated baroreceptor feedback loop process (McCraty et al., 1996). This fast cardiac interoceptive pathway has been found in animal studies, linking heartbeat dynamics to neural activity in the olfactory bulb, hippocampus, and frontal cortices (Hamill, 2024).

Human studies using non-invasive combined techniques (e.g. EEG, ECG, fMRI, etc.) found that heart fluctuations and brain oscillations exhibit synchronous patterns. Robust phase-amplitude couplings have been observed between HF-HRV and EEG oscillations in all frequency bands (Sargent et al., 2024). Using combined fMRI-ECG recordings, directional couplings between heartbeat oscillations centered at ∼0.1 Hz and slow BOLD oscillations were also found in the cerebral cortex and brainstem relevant to fMRI-related anxiety processing (Pfurtscheller et al., 2018). The previously established heartbeat-evoked potential (HEP) captures neural responses to the heartbeat, representing cortical processing of cardiac interoception (Montoya et al., 1993). Researchers have obtained HEP amplitudes primarily in the 200–600 ms time window after the R-peak, which is thought to be associated with diverse cognitive and emotional processes (Park & Blanke, 2019). Studies have found that negative emotions have the greatest attenuation compared to positive emotions (MacKinnon et al., 2013). It has also been reported that the HEP amplitude at frontal electrodes becomes more negative when participants make affective judgments about visual facial stimuli (Fukushima et al., 2011). However, the dynamics of brain activity during the slower heartbeat oscillations remain unidentified, and its role in emotional processing is still under exploration.

Manipulation of the cardiac interoceptive pathway influences emotional and cognitive processing, affecting behavioral performance. For instance, controlled increasing heart rate (HR) in mice enhanced anxiety-like behavior (Hsueh et al., 2023), while biofeedback-based operant manipulations that decreased HR exhibited anxiolytic behavior (Yoshimoto et al., 2024). Cardiac interoception interventions and manipulations such as the mindfulness approaches, and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) have been found to alleviate stress and improve specific behavioral performance (Weng et al., 2021).

It is widely recognized that autonomously controlled breathing in humans modulates cardiac activity, inducing rapid internal fluctuations in physiological states (Laborde et al., 2022). Compared to spontaneous breathing (SB), slow-paced breathing (SPB) at ∼0.1 Hz (∼10 s per breath) stimulates the baroreflex, repatterning the heartbeat oscillation and inducing amplified HRV in the range of ∼0.1 Hz (Lehrer et al., 2000). The higher ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations are associated with improved emotional processing and cognitive functioning (Appelhans & Luecken, 2006). Conversely, decreases in the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations are linked to various physiological and mood disorders, including anxiety and depression (Pfurtscheller et al., 2021). That is, perturbations in cardiac activity may have a causal effect on emotional processing (Mather & Thayer, 2018). Nevertheless, on the brain level, it is necessary to describe the neural processing of the regulatable heartbeat oscillations in the cerebral cortex. Understanding the neural mechanisms underlying the phrase “breathe in calm, breathe out stress” is also a compelling and important question.

This study proposes an electrophysiological index, the so-called heartbeat oscillatory potential (HOP), to provide a dynamic observation for portraying cortical processing to the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations by referring to the extraction method of the event-related potentials (ERPs). Then, a bottom-up SPB regulation technique (breathing at 6 breaths per minute) was utilized to amplify ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, aiming to investigate three basic questions: (1) Does SPB enhance emotional processing? (2) What are the response patterns in terms of HOP related to ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations? (3) How does the interplay between ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations and brain activity affect emotional processing? The study expects to provide promising causal evidence for probing the neural mechanisms underlying the heart-brain circuit and to provide insights into the potential mechanisms of ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations in emotional processing.

MethodParticipantsThis study recruited 108 healthy participants to collect their resting-state data (14 females; mean age = 22.37, SD = 1.80; age range: 18-24), among which 40 males (mean = 22.20, SD = 1.80) continued to participate in the emotional control regulation experiment.

All participants were right-handed and reported no history of psychiatric disorders. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study. Each participant provided written informed consent for the study protocol approved by the ethical committee of the Institutional Review Board.

ProcedureIn this study, 108 participants underwent EEG and ECG recordings for 180s in a resting state, with 40 of these participants proceeding to engage in an emotional control regulation experiment.

Emotional control regulation experimentParticipants completed an emotional control task following two breathing tasks: (1) the spontaneous breathing (SB) task and (2) the SPB task (Fig. 1A). The emotional control task was adapted from a previously established social-emotional approach-avoidance task (AA task) and measured emotional control ability (Bramson et al., 2020) (Fig. 1B). Participants responded to emotional faces (happy or angry) by pressing keys (down arrow for approach, up arrow for avoidance) in congruent and incongruent blocks. In the congruent blocks, participants approached happy faces and avoided angry faces. In the incongruent blocks, participants had to inhibit their natural tendency and execute the counterintuitive action of approaching angry faces and avoiding happy faces (Phaf et al., 2014; Volman et al., 2011). Emotional face stimuli were taken from the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces database: https://kdef.se/. In-task conditions include congruent and incongruent blocks. Four congruent and four incongruent blocks (each block consisting of 12 trials) were presented alternately, with the first block type counterbalanced across participants. Each trial started with a white fixation cross (0.1–0.3s ) followed by emotional face stimuli (0.1s ), with a maximum response window of 2s .

During the SB task, participants sat and stared at a white fixation cross in the center of the computer screen, no specific breathing instructions were given, and breathed spontaneously for 300 s.

During the SPB task, participants were instructed to breathe deeply and slowly at a rate of 0.1 Hz. Inhalation was synchronized with the upward movement of a green square on the screen, and exhalation followed the downward movement (Fig. 1C). Each respiratory duration consisted of a 4 s inhalation followed by a 6 s exhalation, completing a total of 30 cycles.

Psychophysiological recordingThe EEG signal was recorded using a 64-channel acquisition system (Brain Products) with electrode positions according to the international 10–20 system, with online reference to FCz. Electrode impedance was maintained below 5 kΩ The ECG signal was obtained from three electrodes, one placed on the left supraclavicular and one on the right subcostal, with the ground electrode positioned on the back. The respiratory signal was collected using a belt worn around the chest. The respiratory, ECG, and EEG signals were recorded synchronously at a sampling rate of 1 kHz.

Data processingElectrophysiological data preprocessingEEG data were preprocessed using the EEGLAB toolbox (Delorme & Makeig, 2004). The steps included: (1) filtering the offline EEG between 0.5 and 45 Hz using a finite impulse response (FIR) filter; (2) downsampling to 250 Hz; (3) manual inspection to interpolate bad channels, and rejection of trials with significant bias or artifacts; (4) application of Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to remove artifacts such as eye movements and the cardiac-field artifact (CFA); and (5) re-referencing using the Re-Referenced Electrode Standardization Technique (REST) (Yao, 2001).

R-peaks of ECG signal were detected using the Pan-Tompkins algorithm (Pan & Tompkins, 1985), and the inter-beat interval (IBI) was defined as the interval between consecutive R-peaks. The HRV series was constructed from the IBIs, then upsampled to 250 Hz to be consistent with the preprocessed EEG data. The time-dependent measures of HRV, including the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), were calculated. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was performed to calculate the ∼0.1 Hz HRV power (the amplitude of the LF) (Lehrer et al., 2013). Respiration signals were visually inspected and noisy respiratory cycles were manually excluded. The signals were z-scored to extract inhale and exhale onset. The respiratory duration was defined as the time interval between consecutive inhalations.

The following analysis framework is shown in Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of data analysis. (A) Procedure for HOP extraction. (B) Non-parametric tests of the cortical HOP in source space, including phase-based and marker-based permutation tests. (C) Comparisons between SPB and SB on the averaged HOP amplitude (across all subjects), and the phase distribution analysis of HOP across all HOP trials. (D) Analysis of the difference in actual respiratory rate and respiratory duration on HOP during the SPB task.

The HOP extraction method is similar to HEP. The HEP extraction uses the R-peak of the ECG as the onset and focuses on the neural responses evoked by each heartbeat within 1 s (Pollatos & Schandry, 2004), whereas the HOP extraction method uses the critical point (trough or peak) of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as the onset and focuses more on the neural responses associated with the LF fluctuations. The detailed extraction steps are as follows:

The HRV series were first band-pass filtered between 0.04–0.15 Hz to obtain the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations (that is the LF dominant frequency). The ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillates with approximately a 10 s period. Thus, the pre-processed EEG data were then segmented into 10 s epochs (0–10 s), time-locked to the trough of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations. To rule out potential biases arising from the epoch onset settings, HOP epochs were also extracted using the peak of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as the onset. Further, HOP was extracted across five EEG frequency bands, including delta (0.5–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta(12–30 Hz), and gamma (30–45 Hz).

HOP source estimationA standard structural T1-weighted MRI template (ICBM152) was used to estimate the cortical activity of averaged HOP within the Brainstorm toolbox (Tadel et al., 2011). Forward modeling of neuroelectric fields was computed with the symmetric boundary element method (BEM) using the OpenMEEG toolbox. Cortical HOP estimation was reconstructed using the minimum norm estimation (MNE) approach for inverse modeling.

Statistical analysis of behavioral and physiological indicesEmotional control ability was calculated as the difference in correct rate (CR) between the congruent condition (CC) and incongruent condition (IC) (congruency effect = CRCC- CRIC). Paired t-tests compared the congruency effects between the two breathing conditions (SPB vs. SB). A repeated-measures analysis of variance (2 × 2 within-subjects ANOVA) was conducted with in-task condition (CC vs. IC) and breathing condition (SPB vs. SB) as factors, followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Three participants were excluded from the analysis for not achieving 70 % accuracy.

Paired t-tests examined the effect of SPB on ∼0.1 Hz HRV power, RMSSD, and respiratory rate. Independent sample t-tests investigated the influence of respiratory rate on ∼0.1 Hz HRV power and emotional control ability, categorizing subjects based on median respiratory rate during SPB (respiratory rate > 6.6 bpm vs. respiratory rate < 6.6 bpm). The significance level was set as p < 0.05 for statistical analyses.

Statistical verification of cortical HOP distributionTwo non-parametric statistical methods were designed to test cortical HOP distribution, resulting in statistically significant p-maps:

Maker-based permutation test. To identify the cortical HOP distribution significantly associated with cardiac information, 1000 random onset points were generated across the entire EEG dataset for epoch extraction at the individual subject level. A null distribution was then constructed for each cortical voxel based on these 1000 randomized epochs. The statistical significance of the cortical HOP was evaluated by comparing the observed HOP to the null distribution.

Phase-based permutation test. To identify the cortical HOP distribution significantly associated with phase information, the grand HOP was Fourier-transformed to extract phase data, which was then randomized and shuffled 1000 times. The randomized signals were subsequently transformed back to the time domain via inverse Fourier transform to reconstruct the epoch signals. The cortical HOP was tested against the null distribution formed from the 1000 reconstructed epochs.

Comparisons of HOP between SPB and SBAt the source level, 68 regions of interest (ROIs) were defined using the Desikan-Killiany (DK) atlas, and HOP time series spanning 0 to 10 s were extracted from each ROI. Cluster-based permutation tests, implemented in the FieldTrip toolbox (Oostenveld et al., 2011), were used to compare the HOP time series (0–10 s) between the SPB and SB conditions (1000 permutations). To account for multiple comparisons across time, clusters with corrected p-values below 0.05 are considered significant. The averaged HOP amplitude over time windows with statistically significant differences was taken to calculate the increased/decreased HOP (SPB-SB).

Phase-dependent analysis of HOPFurther, we define the trough of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as the 0 phase and partition the oscillation period into n = 100 equidistant (time windows of 0.1 s). The average HOP amplitude for each 0.1 s time window (each phase point) was compared to the average amplitude over the entire epoch, and the amplitude of the phase point higher than the average amplitude over the entire epoch was taken as a higher HOP trial with dependence on that phase point. The analysis was performed across all HOP trials over subjects and obtained the number of higher HOP trials dependent on each phase point.

A Rayleigh test was performed on the HOP phase distribution for both SB and SPB conditions to assess uniformity (reporting p-values and test statistic z). The Watson-Williams test was used to further evaluate whether the distribution of the two conditions (SPB vs. SB) was identical (reporting p-values and test statistic F). All statistical tests were conducted using the CircStat toolbox (Berens, 2009).

Heart, brain and emotion connectionsMediation modeling was used to examine the directional connections between ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations (index by ∼0.1 Hz HRV power during SPB), the cortical HOP effect (index by increased/decreased HOP), and the emotional control effect (index by congruency effect). In this study, two mediation model hypotheses were proposed with the emotional control effect as the dependent variable (Y):

Model 1: The effect of ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations on emotional control effect is mediated by the cortical HOP effect. In this model, ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as the independent variable (X), and the cortical HOP effect is the mediator (M).

Model 2: The cortical HOP effect on emotional control effect is mediated by the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations. In this model, the cortical HOP effect is the independent variable (X), and ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as the mediator (M).

In this study, SPB significantly enhanced emotional control ability, as indicated by the decreased congruency effect (CRCC- CRIC; t36= −3.74, p < 0.001; Fig. 3A). Two-factor within-subjects ANOVA (level 1: in-task condition, CC vs. IC; level 2: breathing condition, SPB vs. SB) further revealed a significant main effect of in-task condition (F(1,36) = 17.01, p < 0.001), but no main effect of breathing task (F(1,36) = 0.001, p = 0.98). A significant interaction effect between the in-task condition and breathing task was observed (F (1,36) = 13.97, p = 0.001) (Fig. 3B). Post-hoc analysis showed that CR during SPB in the congruent condition was significantly lower than during SB (t = −3.63, p = 0.001), while in the incongruent condition, CR during SPB was significantly higher than during SB (t = 2.96, p = 0.005).

Effects of SPB on emotional control ability and cardiac activity. (A) SPB improved emotional control ability, as indicated by the decreased congruency effect (CRCC- CRIC). Bar chart illustrating the 95 % confidence intervals around the mean of the dependent variable. SB: spontaneous breathing; SPB: Slow-paced breathing; CC: congruent condition; IC: incongruent condition. (B) The CR of the AA task across four conditions was analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons (factor 1:in-task condition, CC vs. IC; factor 2: breathing condition, SPB vs. SB). (C) HRV power spectra of 37 subjects under SPB and SB conditions, showing an increase in the ∼0.1 Hz component of the LF (0.04–0.15 Hz; grey shaded area) during SPB. The purple area represents SPB, while the green area represents SB. (D-E) SPB significantly increased the ∼0.1 Hz HRV power and RMSSD. Each dot corresponds to one participant (*, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001).

The respiratory rate during SPB was significantly lower than during SB (SPB: 7.79 bpm; SB: 15.61 bpm; t36= −14.77, p < 0.001). SPB significantly increased ∼0.1 Hz HRV power (t36= 9.89, p < 0.001; Fig. 3C-D) and RMSSD (t36= 3.55, p = 0.001; Fig. 3E). The mean amplitude frequency of the LF component was 0.097 Hz (SD = 0.012) during SPB and 0.082 Hz (SD = 0.018) during SB.

Time-varying patterns of cortical HOPPhase-based and marker-based permutation tests (sFig. 1) showed that the cortical HOP was primarily distributed in the frontal and parietal cortices, with a time-varying pattern over the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations period (Fig. 4A). We also analyzed the HOP with the peak of ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as the onset (Fig. 4B).

Time-varying distribution of cortical HOP. (A) Cortical distribution of HOP with the trough of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as onset, showing the 10 s time course of the HOP. The top row displays the sec averaged cortical HOP map, with the color bar indicating the absolute source amplitude. Areas without color fall below the minimum value threshold. The purple curve represents the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations. The second row presents the p-maps after the phase-based permutation test of cortical HOP, with the color bar representing p-values and redder colors indicating smaller p-values. (B) Cortical distribution of HOP with the peak of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as the onset.

The results revealed that SPB significantly increased HOP amplitude in eight brain regions, including: (1) right superior frontal; (2) right frontal pole; (3) right rostral middle frontal; (4) right medial orbitofrontal; (5–6) right and left precentral; and (7–8) right and left postcentral (Fig. 5A-B). Moreover, the SPB effect on HOP demonstrated temporal and spatial specificity, with the sustained increased HOP in the right prefrontal cortex around the peak of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations. The comparative analyses of HOP epochs extracted with the peak of ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations as the onset were provided in sFig. 2. Detailed statistics for the comparisons were provided in sTable 1 and sTable 2.

Spatiotemporal effects of SPB on HOP. (A) P-maps of cortical HOP are generated through a phase-based permutation test. The first row displays p maps for the SB condition, while the second row is for the SPB condition, with each p map averaged over seconds. The color bar represents p-values from the permutation test, with the redder reflecting lower p-values. In the SPB condition, significant regions are primarily concentrated in the parietal and right frontal lobes, highlighted by blue circles. (B) Comparison of HOP time series between SB and SPB conditions. Green waveforms represent the HOP time series in the SB condition, and purple waveforms represent the SPB condition. Shaded areas show ±1 SEM around the mean. The HOP time series corresponds to the ROI in the upper right corner. The x-axis represents time, and the y-axis indicates HOP amplitude. The gray area highlights the time windows with significantly higher HOP in SPB.

The effects of SPB on cortical HOP were also investigated in five commonly measured neural frequency ranges. The results showed that the cortical HOP was predominantly involved by low-frequency delta and high-frequency beta and gamma bands in both the SB and SPB conditions (sFig. 3).

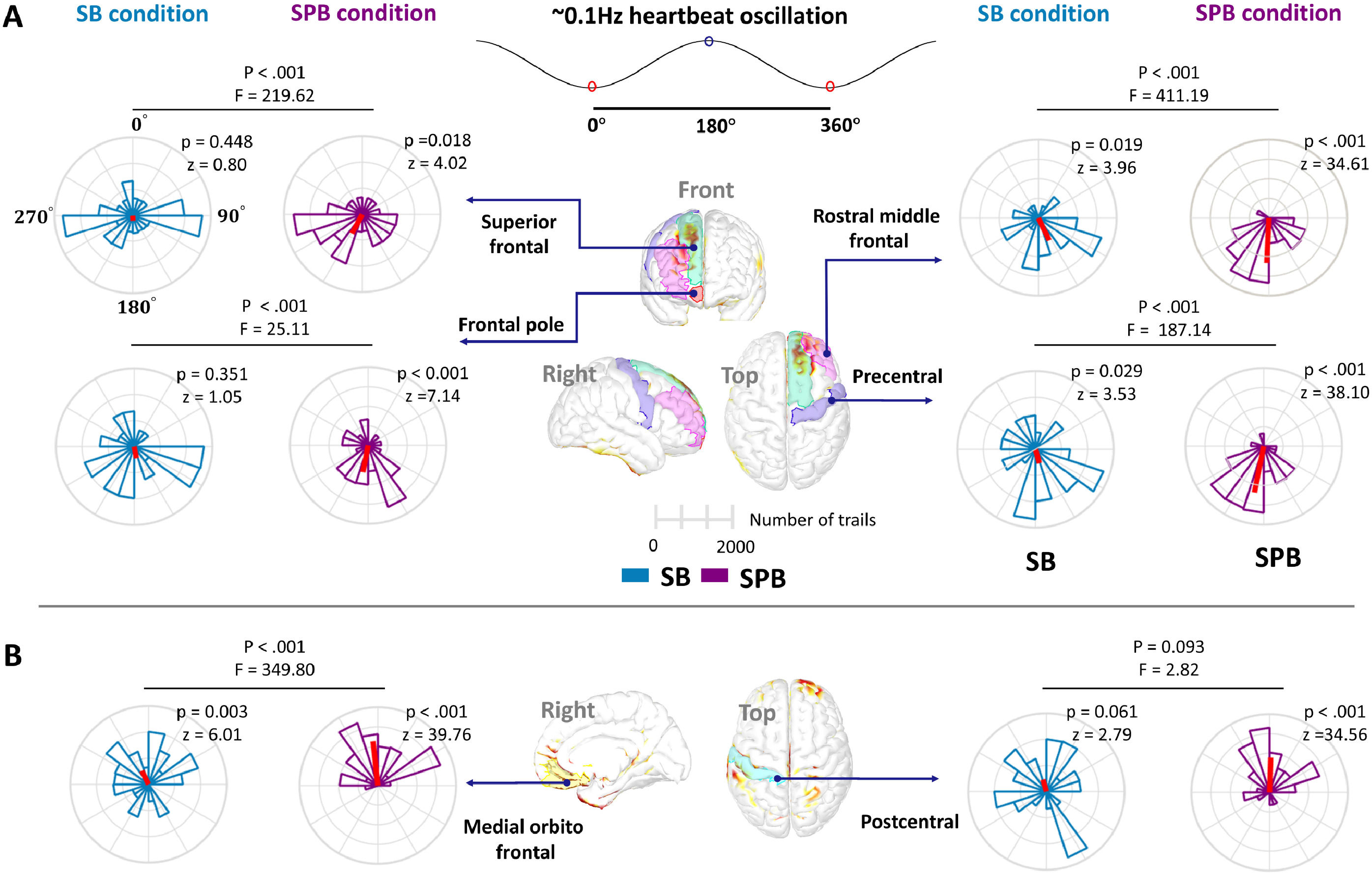

Phase-dependence of HOPIn the SB and SPB conditions, the higher HOP was concentrated within the 120°−240° phase (around the peak of ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations) in the right superior frontal, right frontal pole, rostral middle frontal, and right precentral (Fig. 6A). In the right medial orbitofrontal and right postcentral cortices, higher HOP concentrated between −60° and 60°, around the trough of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations (Fig. 6B). The Watson-Williams test showed that the phase distribution of SPB was more concentrated compared to the SB condition. In addition, the phase distribution of higher HOP trials in the left precentral showed uniformity, but the left postcentral was concentrated between 120°−240° (sFig. 4).

Phase-specific distribution of HOP amplitudes. (A) Phase distribution of higher HOP trials around the peak of ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations in the right frontal lobe and right precentral gyrus. The 0 degree represents the trough of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, 180 degrees for the peak. Green plots represent the phase distribution of higher HOP during SB, while purple plots represent SPB. Red lines indicate the mean phase direction for each plot. Statistical comparisons were conducted across all trials. For visualization purposes, only the top 30 % of the trial distributions with higher HOP amplitude were shown (20 bins). (B) Phase distribution of higher HOP trials around the trough of ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, including right medial orbitofrontal and postcentral.

All participants were divided into two groups by the median respiratory rate during SPB (6.6 bpm): one group with respiratory rates below 6.6 bpm (n = 18, lower respiratory rate group) and the other with respiratory rates above 6.6 bpm (n = 18, higher respiratory rate group) (Fig. 7A). Independent sample t-tests revealed that the lower respiratory rate group exhibited significantly higher ∼0.1 Hz HRV power (t = 2.34, p = 0.025) and enhanced emotional control ability (t = −2.58, p = 0.013) (Fig. 7B). Further, the lower respiratory rate group (< 6.6 bpm) exhibited significantly increased HOP in the right superior frontal (time window: [3.11 - 4.09]s, t = 2.67, p = 0.045) and right rostral middle frontal cortices (time window: [7.44 - 8.80]s, t = 2.71, p = 0.029) (Fig. 7C).

Effect of respiratory rate and respiratory duration on HOP. (A) Scatter plot of respiratory rates. Light blue dots represent the respiratory rates of all subjects during SB, while green, black, and red dots indicate median, above-median, and below-median respiratory rates during SPB, respectively. The x-axis shows the subject number, and the y-axis represents the respiratory rate. (B) Lower respiratory rate subjects exhibited higher ∼0.1 Hz HRV power and improved emotional control ability compared to the higher respiratory rate group. Bar chart illustrating the 95 % confidence intervals around the mean of the dependent variable. (C) Effect of respiratory rate on HOP in superior frontal and rostral middle frontal cortices. Red waveforms represent the HOP time series in the below-median respiratory rate subjects, and purple waveforms represent the above-median respiratory rate subjects. Shaded areas show ±1 SEM around the mean. The HOP time series corresponds to the ROI in the upper right corner. The x-axis represents time, and the y-axis indicates HOP amplitude. Grey areas highlight significant time windows that survive after cluster-based permutations (*, p < 0.05). (D) Scatter plot of respiratory duration. Each point represents a respiratory cycle, with dark blue dots indicating cycles longer than the 9.3 s median duration, and grey dots representing shorter cycles. (E) Effect of respiratory duration on HOP in the superior frontal cortex.

All respiratory trials were divided based on the median breathing period (9.4s ) into long and short respiratory trials (Fig. 7D). The HOP epochs during two respiratory trials were extracted and compared. A significant increase in HOP was observed in the right superior frontal cortex within the time window of [5.99 - 6.89] s (t = 2.36, p = 0.043) during long respiratory trials (Fig. 7E).

Links between ∼0.1 Hz HRV, HOP, and emotional controlOur data supported model 1 and indicated that the increased HOP in the right superior frontal significantly mediated the relationship between ∼0.1 Hz HRV power during SPB and enhanced emotional control (indirect effect = 0.134, 95 % CI: [0.012, 0.313], 5000 bootstrap samples; Fig. 8A). In addition, mediation model 2 is not significant (indirect effect = 0.121, 95 % CI: [−0.001, 0.263], 5000 bootstrap samples) (Fig. 8B). We performed the mediation analyses on else brain regions, and the results showed that the HOP effect in these cortices did not significantly mediate the relationship between cardiac activity and emotional control (sTable 3 and sTable 4).

Directional connections between heart-brain interactions and emotional control ability. (A) HOP mediation diagram. Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between ∼0.1 Hz HRV power and enhanced emotional control mediated by increased HOP neural response in the right superior frontal cortex. (B) The ∼0.1 Hz HRV power mediation diagram. The ‘a’ represents the effect of X on M, ‘b’ represents the effects of M on Y, and ‘c' represents the effect of X on Y (total effect). The proportions mediated (95 % confidence interval) are shown in each figure’s center (*, p < 0.05).

Heartbeat oscillations, brain activity, and emotional processing are intricately linked, carrying profound implications for physical and mental health. This study proposed the HOP, a novel central neural index related to ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, and investigated the effects of SPB as an internal neuromodulation technique on HOP and emotional control. Our results reveal a time-varying cortical activity pattern for HOP and a significant phase-dependent increase of HOP in the right prefrontal and parietal cortices during SPB. Mediation analyses further revealed that the cortical HOP effect in the right prefrontal mediated the association between ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations and enhanced emotional control. Overall, these findings suggest that HOP could serve as a reliable physiological index for tracking dynamic heart-to-brain interactions, with the right prefrontal cortex providing an effective neuromodulatory tagging cortex for future enhancements in emotional control.

Cortical HOP is distributed in the prefrontal and parietal corticesThe heart continuously and periodically sends afferent signals to the brain, and the interaction between the afferent signals and associated cortical processing plays a crucial role in emotion. Emerging evidence suggests that the ∼0.1 Hz cardiac frequency, represents an underlying heart-brain circuit mediated by the baroreceptor loop, and encompasses the vagal-mediated feedforward and feedback regulation (Baranauskas et al., 2023). This study focuses on ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations (∼10 s timescale) and proposes the heartbeat oscillatory potential (HOP) as a novel neural index to capture the corresponding neurodynamics of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations. Our results revealed widespread cortical activation in response to ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, predominantly in the frontal and parietal cortices. Frontal regions such as the superior frontal, dorsomedial prefrontal, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, and insula have been suggested as the interoceptive cortices related to the cardiac afferents projection via the vagus nerve (Park & Blanke, 2019). Also, the somatosensory cortex is one of the central autonomic networks with activity related to the somatosensory processing of cardiac interoceptive afferent signals (Park et al., 2018). Taken together, the time-varying cortical maps of HOP reveal the brain activity associated with heartbeat oscillations and verify the robust link between ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations and prefrontal neural dynamics, demonstrating that heart-brain circuits are connected at the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations level.

SPB increased HOP amplitudeSlow and paced breathing significantly amplifies heartbeat oscillations, shaping cardiac interoception (Parviainen et al., 2022). In this study, SPB significantly enhanced heartbeat oscillations around ∼0.1 Hz and emotional control ability. Concurrently, the heart-brain interaction neural index, HOP, showed robust increases in the prefrontal and central cortices. Previous studies have reported that slow breathing can significantly increase BOLD activity within prefrontal regions, which correlates with improved emotional states (Critchley et al., 2015). The fNIRS studies have reported strengthened prefrontal functional connectivity during slow breathing (Candia-Rivera et al., 2022). Furthermore, the HRV power is causally linked to the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and mPFC-left amygdala functional connectivity, facilitating emotional memory-related processing (Cho et al., 2023). The increased HOP in this study supports the theoretical model of neurovisceral integration, suggesting that SPB at 0.1 Hz improved ascending cardiac vagal control, sending prolonged and stronger afferent signals to interoceptive regions, leading to enhanced neural processing of heart-brain interactions in prefrontal and central cortices, thus triggering improvements in emotional processing (Zaccaro et al., 2018).

Phase-dependence neural modulation of HOPOur results further revealed that SPB consistently increased HOP amplitude in the right prefrontal cortex around the peak of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations. In the SPB condition, exhalation prolonged IBI, baroreceptor activation stimulates vagal afferents input to the prefrontal, accompanying the complete release and hydrolysis of acetylcholine. In contrast, inhalation shortens the IBI, baroreceptors are silenced (Sevoz-Couche & Laborde, 2022). The peak of the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, where the longer IBIs occur, maybe the key to the widely beneficial effects of SPB, which are related to the strongest cardiac vagal control (He, 2020). Supporting this, prior studies demonstrated that prefrontal and central cortices exhibit greater activation during the longest IBIs compared to the shortest IBIs, emphasizing the modulatory role of vagal control on the heartbeat (Patron et al., 2019). This finding suggests that the ascending interoceptive pathway exerts a periodic modulatory influence on information integration in the prefrontal cortex. Meanwhile, we also performed analyses at the individual level to confirm the comprehensive benefits of slower breath frequency and longer respiratory cycles in subjects on ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, cortical HOP activity, and emotional control behaviors.

HOP effect in the right prefrontal cortex as a mediator in emotional controlScholars have suggested that causally manipulating interoceptive pathways is a promising avenue for understanding how the body contributes to emotion. In this study, cardiac interoceptive was manipulated through SPB to investigate the link between heart-brain interactions and emotional control. The result revealed that the cortical HOP effect mediated the association between ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations and enhanced emotional control. The directional hypothesis of Model 1 is supported, that is, the enhanced emotional control was directly influenced by the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillations, and also mediated by the enhanced processing of cardiac interoceptive in the prefrontal cortex.

Studies exist demonstrating that lateralization in the prefrontal cortex influences emotion (Taggart & Lambiase, 2011). Previous evidence suggests that heartbeat perception accuracy varies in parallel with HEP in the right frontal cortex, but not in the left (Coll et al., 2021). A PET study demonstrated that stimulating arterial baroreceptors, which are linked to cardiovascular reflex activity, increased regional cerebral blood flow in the right prefrontal cortex (Weisz et al., 2001). An fMRI study revealed a hemispheric asymmetry in low-frequency interplay in the emotional processing of anxious patients (Ghouse et al., 2024). EEG studies have further identified a correlation between beta-band power in the right superior frontal and precentral gyrus with emotional control ability (Bramson et al., 2018). Overall, these findings showed that emotional-related processing appears to involve complex processing spanning central cortical and subcortical regions as well as peripheral systems.

LimitationsSeveral limitations should be noted: (1) the physiological significance of the proposed HOP index requires further validation, such as through fMRI and larger sample sizes; (2) the moderating effects of slow breathing need to be explored individually to develop optimal personalized breathing protocols; (3) various modulation techniques could be applied to the prefrontal cortex to further investigate heart-brain interactions at the ∼0.1 Hz heartbeat oscillation level; and (4) the emotional face stimuli used in the emotion control task may evoke unique psychophysiological response patterns due to cultural differences. (5) Lastly, the main subjects included in this study were males, and future studies will expand the sample size to explore gender differences.

Availability of data and materialsData in the present study can be made available upon request to the primary contact author.

Ethical approvalThe experimental procedures and physiological measurements were approved by the Ethics Commission of the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, under protocol number 106,142,021,030,917, with approval granted in March 2021.

FundingThis work was supported by grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (62471116); STI 2030—Major Projects (2022ZD0208500); Project of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2024YFG0012); Space Medical Experiment Project of CMSP (HYZHXMN01013).

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.